Psychometric Properties of the Positive Thinking Skills Scale (PTSS) among Portuguese Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Positive and Negative Thinking

1.2. The Positive Thinking Skills Scale

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

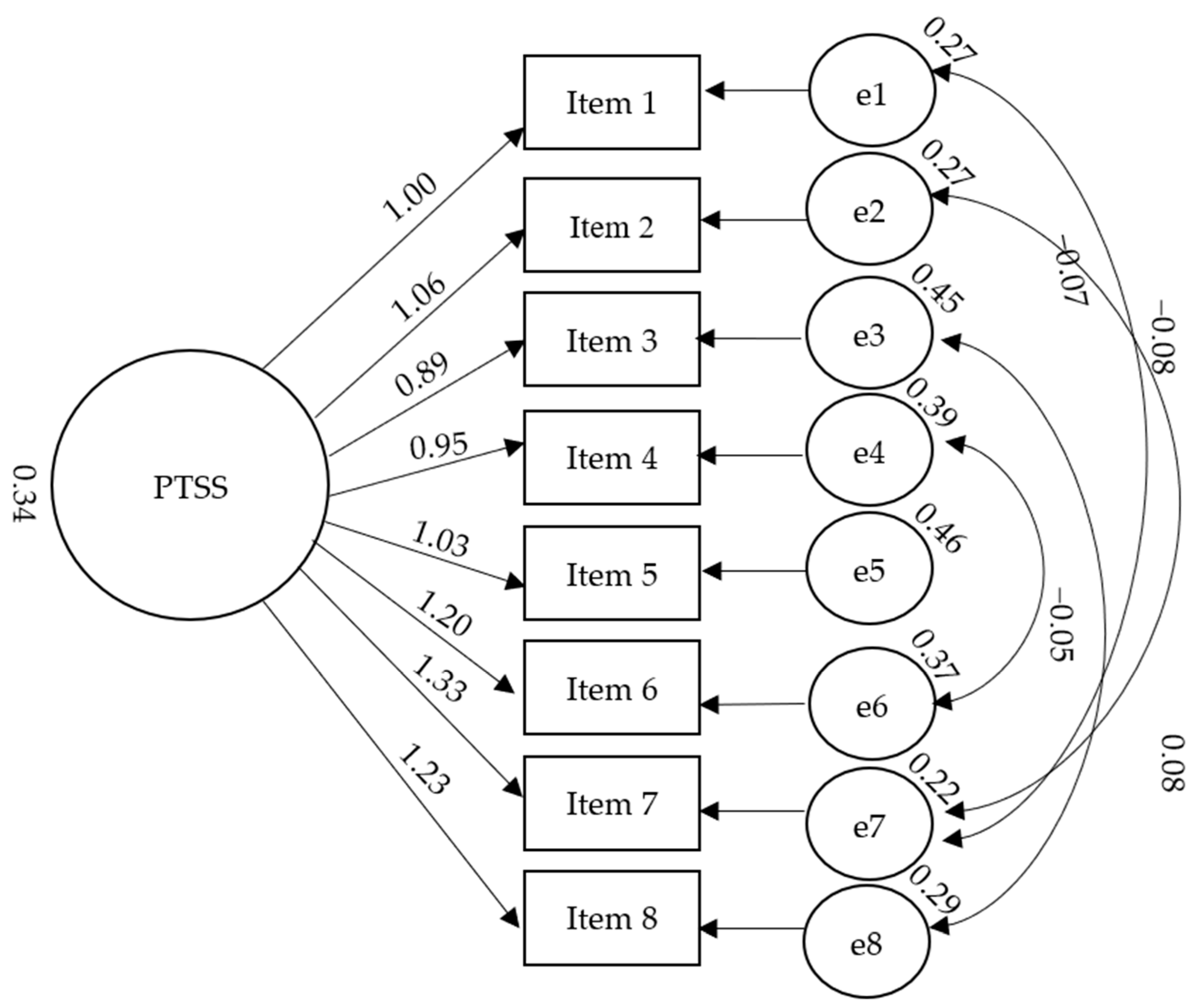

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.3. Reliability

3.4. Convergent and Criterion Validity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johnson, S.L. Therapist’s Guide to Clinical Intervention, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bekhet, A.; Zauszniewski, J. Measuring use of Positive Thinking Skills Scale: Psychometric testing of a new scale. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2013, 35, 1074–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noguchi, K.; Gohm, C.L.; Dalsky, D.J. Cognitive tendencies of focusing on positive and negative information. J. Res. Pers. 2006, 40, 891–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrache, C.G.; Windle, G.; Herrera, R.R. Do social resources explain the relationship between optimism and life satisfaction in community-dwelling older people? Testing a multiple mediation model. J. Happiness Stud. 2015, 16, 633–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, P. The burden of ‘RA RA’ positive: Survivors’ and hospice patients’ reflection on maintaining a positive attitude to serious illness. Support Care Cancer 2004, 12, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseem, Z.; Khalid, R. Positive thinking in coping with stress and health outcomes: Literature review. J. Res. Reflect. Educ. 2010, 4, 42–61. [Google Scholar]

- Southwick, S.M.; Charney, D.S. Resilience: The Science of Mastering life’s Greatest Challenges; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schimmel, S. Vices, virtues and sources of human strength in historical perspective. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 19, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherian, S.; Borhani, F.; Zadeh, A.A.; Ranjbar, H.; Solaimani, F. The effect of distraction by bubble-making on the procedural anxiety of injection in Thalassemic school-age children in Kerman Thalasemia center. Adv. Nurs. Midwifery 2012, 22, 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Bohlmeijer, E.; Westerhof, G. The model for sustainable mental health: Future directions for integrating positive psychology into mental health care. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 747999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Tugade, M.M.; Waugh, C.E.; Larkin, G.R. What good are positive emotions in crisis? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 84, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive psychology: An introduction. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; King, L.; Diener, E. The Benefits of Frequent Positive Affect: Does Happiness Lead to Success? Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 803–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantor, N.; Norem, J.; Langston, C.; Zirkel, S.; Fleeson, W.; Cook-Flannagan, C. Life tasks and daily life experience. J. Pers. 1991, 59, 425–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A.; Bergeman, C.; Bisconti, T.; Wallace, K. Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 91, 730–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunker, S.; Colquhoun, D.; Esler, M.; Hickie, B.I.; Hunt, D.; Jelinek, V.M.; Oldenburg, B.F.; Peach, H.G.; Ruth, D.; Tennant, C.C.; et al. “Stress” and coronary heart disease: Psychosocial risk factors. Med. Stud. J. Aust. 2003, 178, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, A.F.; Bovbjerg, D.H.; Zachariae, R. Stress and susceptibility to infectious disease. In The Handbook of Stress Science: Biology, Psychology, and Health; Contrada, R.J., Baum, A., Eds.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 425–445. [Google Scholar]

- Stojanovich, L.; Marisavljevich, D. Stress as a trigger of autoimmune disease. Autoimmun. Rev. 2008, 7, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugade, M.M.; Frederickson, B.L. Resilient persons use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotions experiences. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 86, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achat, H.; Kawachi, I.; Spiro, A.; DeMolles, D.A.; Sparrow, D. Optimism and depression as predictors of physical and mental health functioning: The Normative Aging Study. Ann. Behav. Med. 2000, 22, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shokrpour, N.; Sheidaie, S.; Amirkhani, M.; Bazrafkan, L.; Modreki, A. Effect of positive thinking training on stress, anxiety, depression, and quality of life among hemodialysis patients: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2021, 10, 225. [Google Scholar]

- Craske, M.G. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, 2nd ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, R.G.; Garland, A. Cognitive Therapy for Chronic and Persistent Depression; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A.S. Ordinary magic: Resilience process in development. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S.; Read, M.J. Resilience in development. In Handbook of Positive Psychology; Snyder, C.R., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhardt, M.; Dolbier, C. Evaluation of a resilience intervention to enhance coping strategies and protective factors and decrease symptomatology. J. Am. Coll. Health 2008, 56, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matel-Anderson, D.M.; Bekhet, A.K. Psychometric properties of the positive thinking skills scale among college students. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2019, 33, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yates, T.M.; Tyrell, F.; Masten, A.S. Resilience theory and the practice of positive psychology from individuals to societies. In Positive Psychology in Practice: Promoting Human Flourishing in Work, Health, Education, and Everyday Life, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bekhet, A.K.; Garnier-Villarreal, M. The positive thinking skills scale: A screening measure for early identification of depressive thoughts. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2017, 38, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S. Negative thinking versus positive thinking in a Singaporean student sample: Relationships with psychological well-being and psychological maladjustment. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2012, 22, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehring, T.; Zetche, U.; Weidacker, K.; Schonfeld, S.; Ehlers, A. The Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire (PTQ): Validation of a content-independent measure of repetitive negative thinking. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2011, 42, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hur, J.; Heller, W.; Kern, J.L.; Berenbaum, H. A bi-factor approach to modeling the structure of worry and rumination. J. Exp. Psychopathol. 2017, 8, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, P.M.; Brans, S. Common versus unique variance across measures of worry and rumination: Predictive utility and mediational models for anxiety and depression. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2013, 37, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Robles, A.; Díaz-García, A.; Miguel, C.; García-Palacios, A.; Botella, C. Comorbidity and diagnosis distribution in transdiagnostic treatments for emotional disorders: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin, A.; Uysal, R.; Akin, U. The validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the Positive Thinking Skills Scale. Eur. J. Educ. 2015, 5, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bekhet, A.K.; Nakhla, V.; Gohar, I.E.; Oudeh, R.; Gergis, M.; Malik, N. Cross-Cultural adaptation and psychometric properties of the Arabic version of the Positive Thinking Skills Scale. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 41, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekhet, A.K.; Matel-Anderson, D. Risk and protective factors in the lives of caregivers of persons with autism: Caregivers’ perspectives. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2017, 53, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barjoee, L.K.; Amini, N.; Keykhosrovani, M.; Shafiabadi, A. Effectiveness of positive thinking training on perceived stress, metacognitive beliefs, and death anxiety in women with breast cancer: Perceived stress in women with breast cancer. Arch. Breast Cancer 2022, 9, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghloo, A.; Shamsaee, P.; Hesari, E.; Akhondzadeh, G.; Hojjati, H. The effect of positive thinking training on the quality of life of parents of adolescent with thalassemia. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2019, 34, 10.1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magson, N.R.; Rapee, R.M.; Fardouly, J.; Forbes, M.K.; Richardson, C.E.; Johnco, C.J.; Oar, E.L. Measuring repetitive negative thinking: Development and validation of the Persistent and Intrusive Negative Thoughts Scale (PINTS). Psychol. Assess. 2019, 31, 1329–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peixoto, M.; Cunha, O. Translation and validation for the portuguese adult population of the Persistent and Intrusive Negative Thoughts Scale: Assessing measurement invariance. Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 2021, 14, 724–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, J.; Pereira, A.; Bártolo, A. development and psychometric properties of a scale to measure resilience among Portuguese university students: Resilience Scale-10. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marôco, J. Análise de Equações Estruturais: Fundamentos Teóricos, Software & Aplicações; ReportNumber, Lda: Pêro Pinheiro, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Bearden, W.O.; Sharma, S. Scaling Procedures: Issues and Applications; Sage: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gravetter, F.; Wallnau, L. Essentials of Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: Wadsworth, OH, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, Z.; Liang, H.; Qin, X.; Ge, Y.; Xiang, N.; Liu, E. Optimism and survival: Health behaviors as a mediator-a ten-year follow-up study of Chinese elderly people. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P.; Rashid, T.A.C.; Parks, A.C. Positive psychotherapy. Am. Psychol. 2006, 61, 774–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabouri, F.; Rambod, M.; Khademian, Z. The effect of positive thinking training on hope and adherence to treatment in hemodialysis patients: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychol. 2023, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbarinejhad, H.S.; Faroughi, P. Comparison of the effectiveness of positive thinking training and acceptance and commitment therapy on quality of life and resilience of people living with HIV. HIV AIDS Rev. 2021, 21, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Paas, L.J.; Morren, M. Please do not answer if you are reading this: Respondent attention in online panels. Mark. Lett. 2018, 29, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherkhani, Z.; Kaveh, M.H.; Mani, A.; Ghahremani, L.; Khademi, K. The effect of positive thinking on resilience and life satisfaction of older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Education | ||

| Higher Education (Bachelor’s, Master’s, Doctorate) | 139 | 63.2 |

| Secondary Education (10th to 12th year) | 76 | 34.5 |

| Elementary Education (7th to 9th year) | 5 | 2.3 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 177 | 80.5 |

| Male | 43 | 19.5 |

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Heterosexual | 178 | 80.9 |

| Homosexual | 7 | 3.2 |

| Bisexual | 23 | 10.5 |

| Pansexual | 5 | 2.3 |

| Undefined | 7 | 3.2 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 188 | 85.5 |

| Married | 28 | 12.7 |

| Divorced | 4 | 1.8 |

| Professional Situation | ||

| Student | 106 | 48.2 |

| Employed | 95 | 43.2 |

| Unemployed | 19 | 8.6 |

| Items | β (Standardized) |

|---|---|

| 0.762 |

| 0.776 |

| 0.687 |

| 0.735 |

| 0.716 |

| 0.785 |

| 0.820 |

| 0.845 |

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Item 1 | - | 0.66 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.57 ** |

| 2. Item 2 | - | 0.50 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.56 ** | |

| 3. Item 3 | - | 0.49 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.47 ** | 0.55 ** | ||

| 4. Item 4 | - | 0.40 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.63 ** | |||

| 5. Item 5 | - | 0.61 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.52 ** | ||||

| 6. Item 6 | - | 0.69 ** | 0.61 ** | |||||

| 7. Item 7 | - | 0.70 ** | ||||||

| 8. Item 8 | - |

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PTSS | - | −0.19 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.53 ** |

| 2. PINTS | - | −0.28 ** | −0.23 ** | −0.28 ** | |

| 3. RS-10 Total | - | 0.93 ** | 0.93 ** | ||

| 5. Self-determination | - | 0.74 ** | |||

| 6. Adaptability | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almeida, T.C.; Ifrim, I.C. Psychometric Properties of the Positive Thinking Skills Scale (PTSS) among Portuguese Adults. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13050357

Almeida TC, Ifrim IC. Psychometric Properties of the Positive Thinking Skills Scale (PTSS) among Portuguese Adults. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(5):357. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13050357

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmeida, Telma Catarina, and Ionela Catalina Ifrim. 2023. "Psychometric Properties of the Positive Thinking Skills Scale (PTSS) among Portuguese Adults" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 5: 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13050357

APA StyleAlmeida, T. C., & Ifrim, I. C. (2023). Psychometric Properties of the Positive Thinking Skills Scale (PTSS) among Portuguese Adults. Behavioral Sciences, 13(5), 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13050357