Pro-Environmental Behavior and Climate Change Anxiety, Perception, Hope, and Despair According to Political Orientation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Climate Change

1.2. Pro-Environmental Behavior

1.3. Climate Change Anxiety

1.4. Climate Change Perception

1.5. Climate Change Hope

1.6. Climate Change Despair

1.7. Political Orientation

1.8. Relationship between Pro-Environmental Behaviors and Climate Change Anxiety, Perception, Hope, and Despair

1.9. Relationship between Pro-Environmental Behavior and Sociodemographic Variables

1.10. Relationship between Pro-Environmental Behavior and Politic Orientation

1.11. Gap, Objectives, and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Sociodemographic Questionnaire and Political Questions

2.2.2. Pro-Environmental Behavior Scale (PEBS)

2.2.3. Climate Change Anxiety Scale (CCAS)

2.2.4. Climate Change Perception Scale (CCPS)

2.2.5. Climate Change Hope Scale (CCHS)

2.2.6. Climate Change Despair Scale (CCDS)

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample

3.2. Descriptive

3.3. Validation

3.3.1. Pro-Environmental Behavior Scale

- (a)

- A confirmatory factor analysis of the original model proposed by the authors was carried out. In Table 1, the model results are presented, being that the model with three factors, ten items, and three correlations between errors (theoretically supported) is the one that presented the best fit.

- (b)

- Results from the measurement invariance of the PEBS across different political orientations are displayed in Table 2. Configural invariance according to political orientation was confirmed during the first step of the multi-group CFA. The small changes in the fit indices in the next steps also supported metric invariance according to political orientation. In addition, the increase in the level of measurement invariance at the subsequent steps did not present a significant deterioration of the models’ fit; also, error invariance across political orientation was achieved, providing strong evidence that the PEBS operates similarly across different political orientations (left, center, and right). Most of the differences were below 0.01, supporting different levels of measurement equivalence between political orientations (Table 2).

- (c)

- Reliability indices results for the PEBS’ factors are displayed in Table 3. No differences between the Cronbach’s alpha (α) and McDonald’s omega (ω) were observed, except for transportation choice, whose McDonald’s omega could not be calculated because this factor only contains two items. This factor also presents a very low value of Cronbach’s alpha. In spite of this, the PEBS is a reliable measure. In addition, the composite reliability, average variance extracted (AVE), square root of AVE, mean, and standard deviation were calculated (Table 3), and almost all of these values were within the reference range.

- (d)

- Statistically significant differences were found in relation to gender with regard to the household behavior (t(198,423) = −2.234; p = 0.027; d = 0.662; men, M = 4.06, SD = 0.75; women, M = 4.22, SD = 0.63) and information seeking (t(533) = −3.512; p < 0.001; d = 1.003; men, M = 2.42, SD = 1.01; women, M = 2.77, SD = 1.00) subscales; women presented higher values than men. Age correlated positively and significantly with the household behavior (r = 0.093; p = 0.032) and information seeking (r = 0.154; p < 0.001) subscales.

3.3.2. Climate Change Anxiety Scale

- (a)

- In order to validate the climate change anxiety scale for this population, a confirmatory factor analysis of the original model proposed by the authors was carried out. The models found are presented in Table 4, and the one with the best fit was the four-factor model with 22 items, which had six correlations between errors of the same factor and, therefore, is theoretically supported.

- (b)

- Results from the measurement invariance of the CCAS across different political orientations are displayed in Table 5. Configural invariance according to political orientation was confirmed during the first step of the multi-group CFA. Small changes in the fit indices in the next steps also supported metric invariance according to political orientation. In addition, the increase in the level of measurement invariance at the subsequent steps did not present a significant deterioration of the models’ fit. However, error invariance across political orientations was not achieved because the difference in the CFI between the scalar and error invariance was 0.024 (above the reference values), providing evidence that the CCAS operates similarly across different political orientations (left, center, and right) regarding configural, metric, and scalar invariance (Table 5).

- (c)

- Reliability indices for the CCAS’ factors are displayed in Table 6. No differences between Cronbach’s alpha (α) and McDonald’s omega (ω) were observed. In spite of the fact that the AVE values for cognitive emotional impairment and behavioral engagement are below the reference values, the CCAS is a reliable measure. Also, behavioral engagement presented higher mean values than the other subscales.

- (d)

- Statistically significant differences were found in relation to gender with regard to the climate change anxiety-related cognitive emotional impairment (t(533) = −2.079; p = 0.007; d = 0.555; men, M = 1.53, SD = 0.54; women, M = 1.68, SD = 0.56), behavior engagement (t(533) = −4.009; p < 0.001; d = 0.587; men, M = 3.53, SD = 0.64; women, M = 3.77, SD = 0.57) and functional impairment (t(533) = −2.062; p = 0.040; d = 0.616; men, M = 1.43, SD = 0.59; women, M = 1.56, SD = 0.62) subscales; women presented higher values than men. There are statistically significant differences in the values of the CCAS for personal experience with climate change concerning political orientation (F(2, 532) = 3.718; p = 0.025; η2 = 0.014): left political orientation, M = 1.11, SD = 0.43; versus center political orientation, M = 0.99, SD = 0.39; versus right political orientation, M = 1.10, SD = 0.39), and the post hoc Tukey test showed that these statistically significant differences occurred between the left and the center.

3.3.3. Climate Change Perception Scale

- (a)

- With the aim of validating the climate change perception scale for this population, a confirmatory factor analysis of the original model proposed by the authors was carried out. A second-order model with three factors and eight items presented a very good fit (χ2(17) = 1.81; IFI = 0.995; TLI = 0.992; CFI = 0.995; GFI = 0.986; SRMR = 0.015; RMSEA = 0.039 (CI90% LO90 = 0.015; HI90 = 0.061); AIC = 68.78), confirming the authors’ model.

- (b)

- Results from the measurement invariance of the CCPS across political orientations are displayed in Table 7. Configural invariance according to political orientation was confirmed during the first step of the multi-group CFAs. However, metric, scalar, and error invariance across political orientations was not achieved because the differences in the RMSEA, CFI, and SRMR values between them were mostly above the reference values, providing evidence that the CCAS operates differently across different political orientations (left, center, and right) (Table 7).

- (c)

- Reliability indices for the CCPS’ factors are displayed in Table 8. No differences between the Cronbach’s alpha (α) and McDonald’s omega (ω) were observed, except for the reality group, whose McDonald’s omega could not be calculated because this group only contains two items. Furthermore, the composite reliability, average variance extracted (AVE), square root of AVE, mean, and standard deviation were calculated (Table 8) and almost all of these values were within the reference range.

- (d)

- Statistically significant differences were found in relation to gender with regard to the CCPS total (t(177, 977) = −3.177; p = 0.002; d = 0.687; men, M = 6.30, SD = 0.87; women, M = 6.59, SD = 0.62), reality (t(170, 909) = −3.518; p < 0.001; d = 0.809; men, M = 6.36, SD = 1.07; women, M = 6.71, SD = 0.70), causes (t(533) = −2.707; p = 0.007; d = 0.979; men, M = 6.13, SD = 1.06; women, M = 6.40, SD = 0.95), and consequences (t(192, 759) = −2.396; p = 0.018; d = 0.718; men, M = 6.50, SD = 0.83; women, M = 6.69, SD = 0.68) subscales; women presented higher values than men. Age correlates negatively and significantly with total (r = −0.119; p = 0.006), reality (r = −0.110; p < 0.011) and causes (r = −0.134; p = 0.002) subscales. There are statistically significant differences in the values of the CCPS total (F(2, 532) = 4.325; p = 0.014; η2 = 0.016); CCPS reality (F(2, 532) = 4.018; p = 0.019; η2 = 0.015); and CCPS consequences (F(2, 532) = 3.109; p = 0.045; η2 = 0.012) concerning political orientation. Regarding the total factor, the results for the left political orientation (M = 6.65; SD = 0.58) versus center political orientation (M = 6.51; SD = 0.72) versus right political orientation (M = 6.43; SD = 0.75) from the post hoc Tukey test showed that statistically significant differences occurred between the left and the right. Concerning the reality factor, the results for the left political orientation (M = 6.74; SD = 0.66) versus center political orientation (M = 6.66; SD = 0.78) versus right political orientation (M = 6.50; SD = 0.96) from the post hoc Tukey test showed that the statistically significant differences occurred between the left and the right. Concerning the consequences factor, the results for the left political orientation (M = 6.76; SD = 0.58) versus center political orientation (M = 6.62; SD = 0.79) versus right political orientation (M = 6.57; SD = 0.76) from the post hoc Tukey test showed that the statistically significant differences occurred between the left and the right.

3.3.4. Climate Change Hope Scale

- (a)

- With the goal of validating the author’s model of the climate change hope scale for our sample, a confirmatory factor analysis was carried out and a good model fit was achieved. This model is a unidimensional one, with eight items and three correlations between errors (Table 9).

- (b)

- Results from the measurement invariance of the CCHS across different political orientations are displayed in Table 10. Configural invariance according to political orientation was confirmed during the first step of the multi-group CFA. The small changes in the fit indices at the next steps also supported metric invariance according to political orientation. Additionally, the increase in the level of measurement invariance in the subsequent steps did not present a significant deterioration of the models’ fit; also, error invariance across political orientation was achieved, providing strong evidence that the CCHS operates similarly across different political orientations (left, center, and right). Most of the differences were below 0.01, supporting different levels of measurement equivalence between political orientations (Table 10).

- (c)

- This scale presents a mean value of 4.42 (SD = 1.24), Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87, McDonald’s omega of 0.87, composite reliability of 0.90, average variance extracted (AVE) of 0.52, and square root of AVE of 0.72.

- (d)

- No differences were found in this scale concerning sociodemographic and political variables.

3.3.5. Climate Change Despair Scale

- (a)

- To validate the authors’ model of the climate change despair scale for our sample, a confirmatory factor analysis was carried out and a good model fit was achieved (χ2(2) = 2.26; IFI = 0.996; TLI = 0.987; CFI = 0.996; GFI = 0.996; SRMR = 0.022; RMSEA = 0.049 (CI90% LO90 = 0.000; HI90 = 0.100); AIC = 20.52), confirming the authors’ model.

- (b)

- Results from the measurement invariance of the CCDS across different political orientations are displayed in Table 11. Configural invariance according to political orientation was confirmed during the first step of the multi-group CFA. However, metric, scalar, and error invariance across political orientations was not achieved because the differences in the RMSEA, CFI, and SRMR between them were above the reference values, providing little evidence that the CCDS operates differently across different political orientations (left, center, and right) (Table 11).

- (c)

- This model is a unidimensional model, with four items and one correlation between errors. This scale presents a mean of 3.66 (SD = 1.42), Cronbach’s alpha of 0.77, McDonald’s omega of 0.78, composite reliability of 0.85, average variance extracted (AVE) of 0.59, and square root of AVE of 0.77.

- (d)

- No differences were found in this scale concerning the sociodemographic and political variables.

3.4. Associations

3.4.1. Correlations

3.4.2. Regressions

- (e)

- It is mainly age and anxiety behavior engagement that explain, altogether, 36.4% of the outcome’s variable (household behavior) (Table 12). Age, gender, children, anxiety behavior engagement, personal experience with climate change, functional impairment, and hope explain, altogether, 39.4% of the outcome’s variable (information seeking) (Table 12). Lastly, marital status, children, anxiety behavior engagement, and functional impairment explain, altogether, 7.6% of the outcome’s variable (transportation choice) (Table 12).

3.5. Moderations

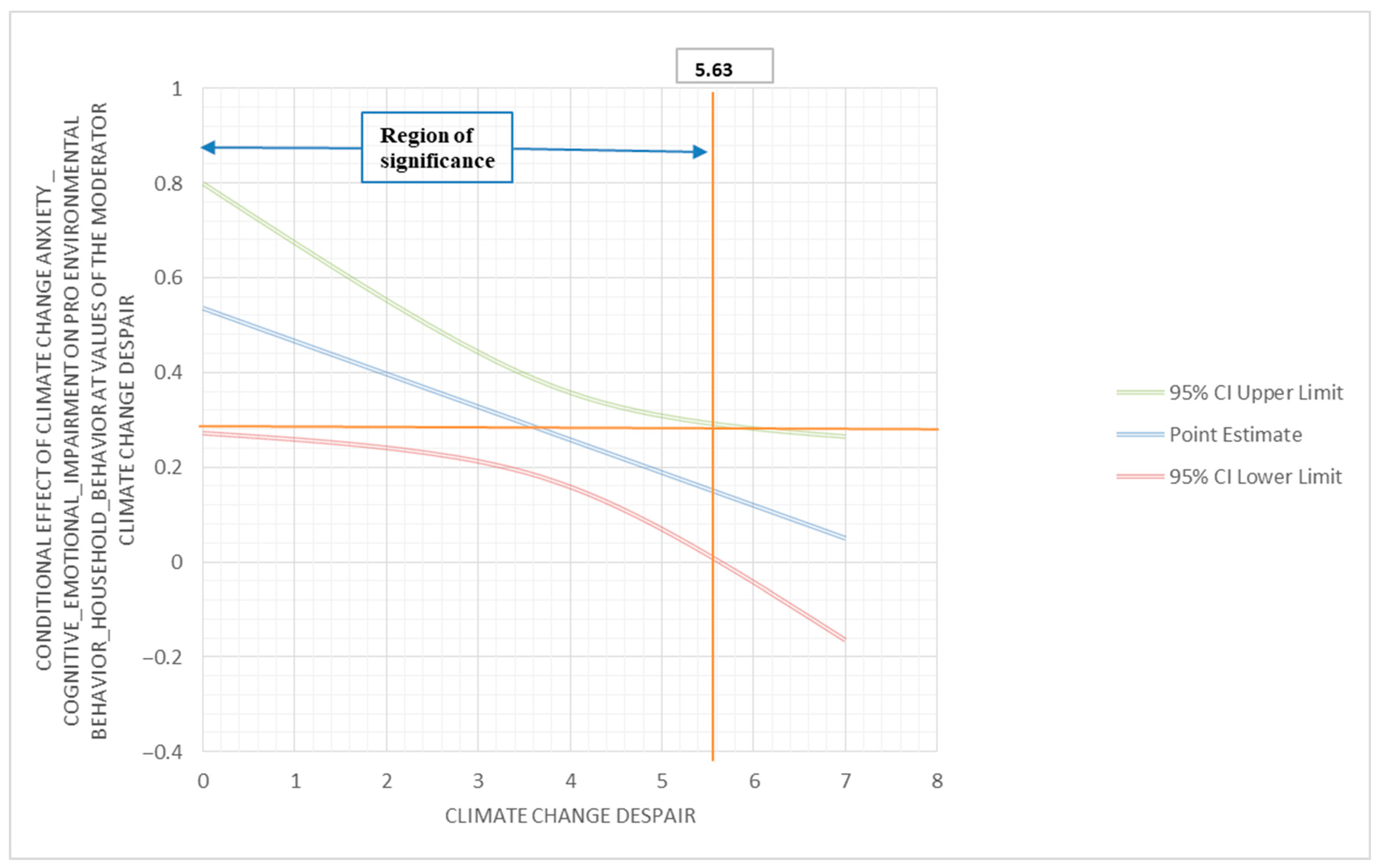

- (f)

- To investigate if despair moderates the relationship between climate change anxiety (cognitive emotional impairment) and pro-environmental behavior (household behavior), a moderator analysis was performed using PROCESS. The outcome variable for this analysis was pro-environmental behavior (household behavior); the predictor variable was climate change anxiety (cognitive emotional impairment); and the moderator variable was despair. The interaction between climate change anxiety (cognitive emotional impairment) and despair was found to be statistically significant (β = −0.07; 95% C.I. (−0.13, −0.01); p < 0.05). The conditional effect of climate change anxiety (cognitive emotional impairment) on pro-environmental behavior (household behavior) showed corresponding results. At the low moderation (2.25), the conditional effect was 0.38, with 95% C.I. (0.24, 0.53), and p < 0.001; at the medium moderation (3.50), the conditional effect was 0.29, with 95% C.I. (0.19, 0.40), and p < 0.001; and at a high moderation (5.25), the conditional effect was 0.17, with 95% C.I. (0.04, 0.30), and p < 0.01. These results identify despair as a negative moderator of the relationship between climate change anxiety (cognitive emotional impairment) and pro-environmental behavior (household behavior). The Johnson–Neyman region of significance is 5.63 (below 89.91% and above 10.09%) (Figure 1).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| M | SD | Var | Sk (SD = 0.106) | Kr (SD = 0.211) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pro-environmental behavior scale | 1–5 | ||||

| 1. Turn off the lights at home when they are not in use. | 4.56 | 0.63 | 0.40 | −1.45 | 2.58 |

| 2. Ask my family to recycle some of the things we use. | 3.91 | 1.12 | 1.25 | −0.89 | 0.11 |

| 3. Ask other people to turn off the water when it is not in use. | 4.38 | 0.88 | 0.77 | −1.53 | 2.20 |

| 4. Close the refrigerator door while I decide what to get out of it. | 4.22 | 1.04 | 1.08 | −1.35 | 1.22 |

| 5. Recycle at home. | 3.83 | 1.23 | 1.52 | −0.80 | −0.34 |

| 6. Choose an environmental topic when I can choose a topic for an assignment in school. | 2.61 | 1.12 | 1.25 | 0.21 | −0.61 |

| 7. Talk with my parents about how to do something about environmental problems. | 2.88 | 1.19 | 1.42 | 0.09 | −0.85 |

| 8. Ask others about things I can do about environmental problems. | 2.56 | 1.19 | 1.42 | 0.33 | −0.77 |

| 9. Walk for transportation. | 3.18 | 1.18 | 1.39 | −0.18 | −0.80 |

| 10. Bike for transportation. | 1.96 | 1.10 | 1.21 | 0.96 | 0.02 |

| Climate change anxiety scale | 1–5 | ||||

| 1. Thinking about climate change makes it difficult for me to concentrate. | 2.24 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.37 | −0.37 |

| 2. Thinking about climate change makes it difficult for me to sleep. | 1.81 | 0.88 | 0.78 | 0.92 | 0.46 |

| 3. I have nightmares about climate change. | 1.41 | 0.70 | 0.49 | 1.80 | 3.33 |

| 4. I find myself crying because of climate change. | 1.29 | 0.62 | 0.38 | 2.16 | 4.03 |

| 5. I think, “why can’t I handle climate change better?” | 1.78 | 0.93 | 0.87 | 0.97 | 0.17 |

| 6. I go away by myself and think about why I feel this way about climate change. | 1.60 | 0.82 | 0.68 | 1.32 | 1.25 |

| 7. I write down my thoughts about climate change and analyze them. | 1.34 | 0.71 | 0.50 | 2.28 | 4.97 |

| 8. I think, “why do I react to climate change this way?” | 1.66 | 0.92 | 0.84 | 1.40 | 1.52 |

| 9. I wish I behaved more sustainably. | 3.47 | 1.03 | 1.06 | −0.54 | 0.14 |

| 10. I recycle. | 3.80 | 1.10 | 1.22 | −0.56 | −0.49 |

| 11. I turn off lights. | 4.50 | 0.70 | 0.49 | −1.45 | 2.43 |

| 12. I try to reduce my behaviors that contribute to climate change. | 3.90 | 0.93 | 0.86 | −0.61 | 0.21 |

| 13. I feel guilty if I waste energy. | 3.40 | 1.04 | 1.07 | −0.05 | −0.54 |

| 14. I believe I can do something to help address the problem of climate change. | 3.20 | 1.00 | 1.01 | −0.02 | −0.31 |

| 15. I have been directly affected by climate change. | 2.46 | 1.03 | 1.07 | 0.31 | −0.43 |

| 16. I know someone who has been directly affected by climate change. | 2.08 | 1.18 | 1.39 | 0.76 | −0.51 |

| 17. I have noticed a change in a place that is important to me due to climate change. | 2.79 | 1.20 | 1.44 | −0.04 | −0.94 |

| 18. My concerns about climate change make it hard for me to have fun with my family or friends. | 1.58 | 0.78 | 0.61 | 1.17 | 0.69 |

| 19. I have problems balancing my concerns about sustainability with the needs of my family. | 1.76 | 0.93 | 0.86 | 1.09 | 0.63 |

| 20. My concerns about climate change interfere with my ability to get work or school assignments done. | 1.42 | 0.68 | 0.46 | 1.59 | 2.02 |

| 21. My concerns about climate change undermine my ability to work to my potential. | 1.44 | 0.72 | 0.52 | 1.67 | 2.50 |

| 22. My friends say I think about climate change too much. | 1.42 | 0.79 | 0.62 | 2.07 | 4.32 |

| Climate change perception scale | 1–7 | ||||

| 1. I believe that climate change is real. | 6.68 | 0.78 | 0.61 | −3.35 | 13.83 |

| 2. Climate change is occurring. | 6.57 | 1.12 | 1.25 | −3.42 | 11.93 |

| 3. Human activities are a major cause of climate change. | 6.29 | 1.05 | 1.11 | −1.93 | 4.57 |

| 4. Climate change is mostly caused by human activity. | 6.38 | 1.01 | 1.03 | −1.96 | 4.09 |

| 5. The main causes of climate change are human activities. | 6.31 | 1.07 | 1.15 | −1.99 | 4.43 |

| 6. Overall, climate change will bring more negative than positive consequences to the world. | 6.62 | 0.85 | 0.72 | −2.70 | 7.85 |

| 7. Climate change will bring about serious negative consequences. | 6.63 | 0.85 | 0.73 | −3.22 | 13.26 |

| 8. The consequences of climate change will be very serious. | 6.69 | 0.73 | 0.53 | −2.90 | 9.61 |

| Climate change hope scale | 0–7 | ||||

| 1. I believe people will be able to stop global warming. | 3.86 | 1.77 | 3.13 | 0.11 | −0.87 |

| 2. I believe scientists will be able to find ways to solve problems caused by climate change. | 4.17 | 1.70 | 2.89 | 0.02 | −0.84 |

| 3. Even when some people give up, I know there will be people who will continue to try to solve problems caused by climate change. | 4.99 | 1.75 | 3.07 | −0.47 | −0.67 |

| 4. Because people can learn from our mistakes, we will influence climate change in a positive direction. | 3.93 | 1.84 | 3.40 | 0.07 | −0.96 |

| 5. Every day, more people care about problems caused by climate change. | 4.60 | 1.67 | 2.79 | −0.22 | −0.74 |

| 6. If everyone works together, we can solve problems caused by climate change. | 5.32 | 1.66 | 2.76 | −0.87 | 0.08 |

| 7. At the present time, I am energetically pursuing ways to solve problems caused by climate change. | 3.63 | 1.64 | 2.70 | 0.13 | −0.54 |

| 8. I know that there are many things that I can do to help solve problems caused by climate change. | 4.88 | 1.76 | 3.11 | −0.42 | −0.80 |

| Climate change despair scale | 0–7 | ||||

| 1. I feel helpless to solve problems caused by climate change. | 3.85 | 1.83 | 3.36 | 0.11 | −0.84 |

| 2. The actions I can take are too small to help solve problems caused by climate change. | 4.06 | 1.98 | 3.93 | −0.02 | −1.08 |

| 3. Problems caused by climate change are out of my control. | 3.72 | 1.89 | 3.55 | 0.23 | −0.94 |

| 4. Climate change is such a complex problem, we will never be able to solve it. | 3.01 | 1.67 | 2.80 | 0.52 | −0.55 |

Appendix B

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PEBS household behavior | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 2. PEBS information seeking | 0.428 ** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 3. PEBS transportation choice | 0.276 ** | 0.284 ** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 4. CCAS cognitive emotional impairment | 0.218 ** | 0.516 ** | 0.195 ** | 1 | |||||||||

| 5. CCAS behavioral engagement | 0.601 ** | 0.473 ** | 0.221 ** | 0.324 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| 6. CCAS personal experience with climate change | 0.258 ** | 0.430 ** | 0.190 ** | 0.481 ** | 0.408 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 7. CCAS functional impairment | 0.180 ** | 0.464 ** | 0.209 ** | 0.651 ** | 0.262 ** | 0.487 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 8. CCPS total | 0.189 ** | 0.173 ** | 0.027 | 0.178 ** | 0.362 ** | 0.190 ** | 0.071 | 1 | |||||

| 9. CCPS reality | 0.141 ** | 0.129 ** | 0.051 | 0.138 ** | 0.297 ** | 0.182 ** | 0.049 | 0.688 ** | 1 | ||||

| 10. CCPS causes | 0.172 ** | 0.162 ** | 0.012 | 0.152 ** | 0.301 ** | 0.143 ** | 0.087 * | 0.873 ** | 0.369 ** | 1 | |||

| 11. CCPS consequences | 0.143 ** | 0.126 ** | 0.015 | 0.145 ** | 0.294 ** | 0.155 ** | 0.028 | 0.856 ** | 0.504 ** | 0.598 ** | 1 | ||

| 12. CCHS total | 0.241 ** | 0.286 ** | 0.155 ** | 0.248 ** | 0.403 ** | 0.231 ** | 0.188 ** | 0.342 ** | 0.249 ** | 0.302 ** | 0.278 ** | 1 | |

| 13. CCDS total | 0.011 | −0.033 | −0.025 | 0.123 ** | 0.020 | 0.016 | 0.092 * | 0.085 * | 0.058 | 0.055 | 0.100 * | 0.004 | 1 |

References

- Edenhofer, O.; Seyboth, K. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). In Encyclopedia of Energy, Natural Resource, and Environmental Economics; Shogren, J.F., Ed.; Elsevier: Waltham, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.J.; Monroe, M.C. Exploring the essential psychological factors in fostering hope concerning climate change. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 936–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.; Leung, A.K.; Clayton, S. Research on climate change in social psychology publications: A systematic review. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 24, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocker, T.F.; Qin, D.; Plattner, G.K.; Tignor, M.M.; Allen, S.K.; Boschung, J.; Nauels, A.; Xia, Y.; Bex, V.; Midgley, P.M. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of IPCC the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Bagrodia, R.; Pfeffer, C.C.; Meli, L.; Bonanno, G.A. Anxiety and resilience in the face of natural disasters associated with climate change: A review and methodological critique. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 76, 102297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, N.; Adger, W.N.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; Bai, Y.; Byass, P.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Colbourn, T.; Cox, P.; Davies, M.; Depledge, M.; et al. The Lancet Countdown: Tracking progress on health and climate change. Lancet 2017, 389, 1151–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Fast Facts 2022. Climate Fast Facts. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/climate-fast-facts (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Palinkas, L.A.; Wong, M. Global climate change and mental health. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 32, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakour, M.J. Disasters and Mental Health. In Routledge Handbook of Environmental Hazards and Society; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 394–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothe, E.J.; Ling, M.; North, M.; Klas, A.; Mullan, B.A.; Novoradovskaya, L. Protection motivation theory and pro-environmental behavior: A systematic mapping review. Aust. J. Psychol. 2019, 71, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, F.; Dewitte, S. Measuring pro-environmental behavior: Review and recommendations. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 63, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilli, G.; Curtis, J. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviors: A review of methods and approaches. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 135, 110039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, F. Behavioral paradigms for studying pro-environmental behavior: A systematic review. Behav. Res. Methods 2022, 55, 600–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, C.D.; Collado, S. Enhancing nature conservation and health: Changing the focus to active pro-environmental behaviors. Psychol. Stud. 2020, 65, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhao, L.; Ma, S.; Shao, S.; Zhang, L. What influences an individual’s pro-environmental behavior? A literature review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L.; Amirbagheri, K.; Hermanns, E.; Merigó, J.M. Celebrating half a century of Environment and Behavior: A bibliometric review. Environ. Behav. 2019, 51, 469–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Karazsia, B.T. Development and validation of a measure of climate change anxiety. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 69, 101434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, C.; Marks, E.; Pihkala, P.; Clayton, S.; Lewandowski, R.E.; Mayall, E.; Wray, B.; Mellor, C.; van Susteren, L. Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: A global survey. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pihkala, P. Anxiety and the ecological crisis: An analysis of eco-anxiety and climate anxiety. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, K.; Gow, K. Do concerns about climate change lead to distress? Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strateg. Manag. 2010, 2, 362–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.E. Psychometric properties of the climate change worry scale. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McQueen, A. The Wages of Fear? In Philosophy and Climate Change; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021; Volume 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, S.K.; Hogg, T.L.; Leviston, Z.; Walker, I. From anger to action: Differential impacts of eco-anxiety, eco-depression, and eco-anger on climate action and wellbeing. J. Clim. Chang. Health 2021, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, T. Ecologies of Guilt in Environmental Rhetorics; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Hope and anticipation in education for a sustainable future. Futures 2017, 94, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74, 102263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrabok, M.; Delorme, A.; Agyapong, V.I. Threats to mental health and well-being associated with climate change. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 76, 102295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Hope and climate change: The importance of hope for environmental engagement among young people. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 625–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghelcev, G.; Chung, M.-Y.; Sar, S.; Duff, B.R. A ZMET-based analysis of perceptions of climate change among young South Koreans: Implications for social marketing communication. J. Soc. Mark. 2015, 5, 56–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoggett, P.; Randall, R. Engaging with climate change: Comparing the cultures of science and activism. Environ. Values 2018, 27, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Regulating Worry, Promoting Hope: How Do Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults Cope with Climate Change? Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2012, 7, 537–561. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, E.K.; Mayer, A. A social trap for the climate? Collective action, trust and climate change risk perception in 35 countries. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 49, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W.; Whitmarsh, L.; Steg, L.; Böhm, G.; Fisher, S. Climate change perceptions and their individual-level determinants: A cross-European analysis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 55, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L. Limiting climate change requires research on climate action. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 759–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Valkengoed, A.; Steg, L.; Perlaviciute, G. Development and validation of a climate change perceptions scale. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 76, 101652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, O. Intelligent accountability in education. In The Public Understanding of Assessment; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Steentjes, K.; Pidgeon, N.F.; Poortinga, W.; Corner, A.J.; Arnold, A.; Böhm, G.; Mays, C.; Poumadère, M.; Ruddat, M.; Scheer, D. European Perceptions of Climate Change (EPCC): Topline Findings of a Survey Conducted in Four European Countries in 2016. 2017. Available online: http://orca.cf.ac.uk/98660/7/EPCC.pDF (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Demski, C.; Capstick, S.; Pidgeon, N.; Sposato, R.G.; Spence, A. Experience of extreme weather affects climate change mitigation and adaptation responses. Clim. Chang. 2017, 140, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Emotion and Adaptation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ojala, M. Hope in the face of climate change: Associations with environmental engagement and student perceptions of teachers’ emotion communication style and future orientation. J. Environ. Educ. 2015, 46, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlon, J.R.; Bloodhart, B.; Ballew, M.T.; Rolfe-Redding, J.; Roser-Renouf, C.; Leiserowitz, A.; Maibach, E. How hope and doubt affect climate change mobilization. Front. Commun. 2019, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, L.; Hill, S.N.; Gaydosh, L.M.; Steinhoff, A.; Costello, E.J.; Dodge, K.A.; Harris, K.M.; Copeland, W.E. Does despair really kill? A roadmap for an evidence-based answer. Am. J. Public Health 2019, 109, 854–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brignone, E.; George, D.R.; Sinoway, L.; Katz, C.; Sauder, C.; Murray, A.; Gladden, R.; Kraschnewski, J.L. Trends in the diagnosis of diseases of despair in the United States, 2009–2018: A retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e037679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, R.L.; Greenburg, J.; Clark, S.G. Confronting anxiety and despair in environmental studies and sciences: An analysis and guide for students and faculty. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2020, 10, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilford, D.; Moser, S.; DePodwin, B.; Moulton, R.; Watson, S. The emotional toll of climate change on science professionals. Eos 2019, 100, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoggett, P. (Ed.) Climate Psychology: On Indifference to Disaster; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, S.; Devine-Wright, P.; Stern, P.C.; Whitmarsh, L.; Carrico, A.; Steg, L.; Swim, J.; Bonnes, M. Psychological research and global climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haltinner, K.; Sarathchandra, D. Climate change skepticism as a psychological coping strategy. Sociol. Compass 2018, 12, e12586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, P.J.; Mullin, M. Climate change: US public opinion. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2017, 20, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Yang, J.Z. Taking climate change here and now–mitigating ideological polarization with psychological distance. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 53, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M. Public environmental skepticism: A cross-national and multilevel analysis. Int. Sociol. 2015, 30, 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsey, M.J.; Harris, E.A.; Bain, P.G.; Fielding, K.S. Meta-analyses of the determinants and outcomes of belief in climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2016, 6, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Kim, S. Analysis of the impact of values and perception on climate change skepticism and its implication for public policy. Climate 2018, 6, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L. Scepticism and uncertainty about climate change: Dimensions, determinants and change over time. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, T.H.; Kay, A.C. Solution aversion: On the relation between ideology and motivated disbelief. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 107, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCright, A.M.; Marquart-Pyatt, S.T.; Shwom, R.L.; Brechin, S.R.; Allen, S. Ideology, capitalism, and climate: Explaining public views about climate change in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 21, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCright, A.M.; Xiao, C.; Dunlap, R.E. Polítical polarization on support for government spending on environmental protection in the USA, 1974–2012. Soc. Sci. Res. 2014, 48, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuldt, J.P.; Konrath, S.H.; Schwarz, N. “Global warming” or “climate change”? Whether the planet is warming depends on question wording. Public Opin. Q. 2011, 75, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, D.H.; Durand, V.M.; Hofmann, S.G. Abnormal Psychology: An Integrative Approach; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tallis, F.; Davey, G.C.L.; Capuzzo, N. The phenomenology of non-pathological worry: A preliminary investigation. In Worrying: Perspectives on Theory, Assessment and Treatment; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1994; pp. 61–89. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Majority of US Adults Believe Climate Change Is Most Important Issue Today. American Psychological Association Website. 2020. Available online: https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2020/02/climate-change (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Visschers, V.H. Public perception of uncertainties within climate change science. Risk Anal. 2018, 38, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Johnson, E.J.; Zaval, L. Local warming: Daily temperature deviations affect both beliefs and concern about climate change. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 22, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, K.; Peterson, N. Motivating action through fostering climate change hope and concern and avoiding despair among adolescents. Sustainability 2015, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, C. Climate change: Against despair. Ethics Environ. 2014, 19, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nairn, K. Learning from young people engaged in climate activism: The potential of collectivizing despair and hope. Young 2020, 27, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Svicher, A. The eco-generativity scale (EGS): A new resource to protect the environment and promote health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, J.M.; McCullough, B.P.; Smith, D.M.K. Pro-environmental sustainability and political affiliation: An examination of USA college sport sustainability efforts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swartz, D.L. Symbolic Power, Politics, and Intellectuals: The Political Sociology of Pierre Bourdieu; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Grindal, M.; Sarathchandra, D.; Haltinner, K. White Identity and Climate Change Skepticism: Assessing the Mediating Roles of Social Dominance Orientation and Conspiratorial Ideation. Climate 2023, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, S.D.; Kenny, J.; Poortinga, W.; Böhm, G.; Steg, L. The politicization of climate change attitudes in Europe. Elect. Stud. 2022, 79, 102499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.J.; Liu, Z.; Safi, A.S.; Chief, K. Climate change perception, observation and policy support in rural Nevada: A comparative analysis of Native Americans, non-native ranchers and farmers and mainstream America. Environ. Sci. Policy 2014, 42, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; McCright, A.M. Gender differences in environmental concern: Revisiting the institutional trust hypothesis in the USA. Environ. Behav. 2015, 47, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloodhart, B.; Swim, J.K. Sustainability and consumption: What’s gender got to do with it? J. Soc. Issues 2020, 76, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Molina, M.; Fernández-Sainz, A.; Izagirre-Olaizola, J. Does gender make a difference in pro-environmental behavior? The case of the Basque Country University students. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 176, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, S.; Sheehan, K. The role of guilt in influencing sustainable pro-environmental behaviors among shoppers: Differences in response by gender to messaging about England’s plastic-bag levy. J. Advert. Res. 2018, 58, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlberg, L.; Gilligan, C. Moral Development. In Developmental Psychology: Revisiting the Classic Studies; Sage Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 164–175. [Google Scholar]

- Corner, A.; Roberts, O.; Chiari, S.; Völler, S.; Mayrhuber, E.S.; Mandl, S.; Monson, K. How do young people engage with climate change? The role of knowledge, values, message framing, and trusted communicators. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2015, 6, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregoire, J. ITC guidelines for translating and adapting tests. Int. J. Test. 2018, 18, 101–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Cross-cultural research methods: Strategies, problems, applications. In Environment and Culture; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1980; pp. 47–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. The mediation myth. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 37, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. LISREL 8: Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language; Scientific Software International: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.F. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2007, 14, 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, I.; Huang, Y.; Chen, J.; Benesty, J. Pearson correlation coefficient. In Noise Reduction in Speech Processing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Fielding, K.S.; Dean, A.J. “Nature is mine/ours”: Measuring individual and collective psychological ownership of nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 85, 101919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, L.C. Education, politics and opinions about climate change evidence for interaction effects. Clim. Chang. 2011, 104, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCright, A.M. Political orientation moderates Americans’ beliefs and concern about climate change: An editorial comment. Clim. Chang. 2011, 104, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malka, A.; Krosnick, J.A.; Langer, G. The association of knowledge with concern about global warming: Trusted information sources shape public thinking. Risk Anal. Int. J. 2009, 29, 633–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, J.T.; Banaji, M.R. The role of stereotyping in system-justification and the production of false consciousness. British J. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 33, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, M.S.; Painter, J. Climate journalism in a changing media ecosystem: Assessing the production of climate change-related news around the world. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2021, 12, e675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, G.J.; Dale, G. Trait anxiety predicts pro-environmental values and climate change action. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2023, 205, 112101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunbode, C.A.; Doran, R.; Hanss, D.; Ojala, M.; Salmela-Aro, K.; Broek, K.L.v.D.; Bhullar, N.; Aquino, S.D.; Marot, T.; Schermer, J.A.; et al. Climate anxiety, pro-environmental action and wellbeing: Antecedents and outcomes of negative emotional responses to climate change in 28 countries. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 84, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Wu, B.; Deng, X.; Li, W. The impact of employees’ pro-environmental behaviors on corporate green innovation performance: The mediating effect of green organizational identity. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 984856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balundė, A.; Perlaviciute, G.; Steg, L. The relationship between people’s environmental considerations and pro-environmental behavior in Lithuania. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.S.; Jianguo, D.; Ali, M.; Saleem, S.; Usman, M. Interrelations between ethical leadership, green psychological climate, and organizational environmental citizenship behavior: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| RMSEA CI 90% | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | DF | χ2/DF | IFI | TLI | CFI | GFI | SRMS | RMSEA | LO90 | HI90 | AIC | |

| Three factors, 10 items | 226.88 | 32 | 7.09 | 0.878 | 0.828 | 0.877 | 0.913 | 0.079 | 0.107 | 0.094 | 0.120 | 272.88 |

| Three factors, 10 items, three correlations between errors | 79.99 | 29 | 2.76 | 0.968 | 0.950 | 0.968 | 0.971 | 0.050 | 0.057 | 0.043 | 0.063 | 131.99 |

| χ2 | DF | χ2/DF | RMSEA (CI) | CFI | IFI | SRMS | Comparisons | Δ RMSEA | Δ CFI | Δ SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configural invariance | 132.56 | 87 | 1.52 | 0.031 (0.020–0.042) | 0.971 | 0.972 | 0.062 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Metric invariance | 156.47 | 101 | 1.54 | 0.032 (0.022–0.042) | 0.965 | 0.966 | 0.063 | Configural vs. metric | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.001 |

| Scalar invariance | 167.87 | 113 | 1.49 | 0.030 (0.020–0.039) | 0.966 | 0.966 | 0.064 | Metric vs. scalar | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Error variance invariance | 198.94 | 139 | 1.43 | 0.028 (0.019–0.037) | 0.962 | 0.962 | 0.065 | Scalar vs. error variance | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.001 |

| Pearson’s Correlations | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | α | ω | CR | AVE | Mean (SD) | |

| 1. Household behavior | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.80 | 0.45 | 4.18 (0.66) | ||

| 2. Information-seeking behavior | 0.428 ** | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.90 | 0.76 | 2.69 (1.01) | |

| 3. Transportation choice | 0.276 ** | 0.284 ** | 0.81 | 0.48 | a | 0.79 | 0.66 | 2.57 (0.92) |

| RMSEA CI 90% | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | DF | χ2/DF | IFI | TLI | CFI | GFI | SRMS | RMSEA | LO90 | HI90 | AIC | |

| Second-order model, four factors, 22 items | 742.24 | 205 | 3.62 | 0.873 | 0.856 | 0.872 | 0.879 | 0.078 | 0.070 | 0.065 | 0.076 | 838.24 |

| Second-order model, four factors, 22 items, six correlations between errors | 485.66 | 199 | 2.44 | 0.932 | 0.921 | 0.932 | 0.922 | 0.061 | 0.052 | 0.046 | 0.058 | 593.66 |

| Four factors, 22 items | 715.39 | 203 | 3.52 | 0.879 | 0.861 | 0.878 | 0.881 | 0.074 | 0.069 | 0.063 | 0.074 | 815.39 |

| Four factors, 22 items, six correlations between errors | 467.31 | 197 | 2.37 | 0.936 | 0.924 | 0.936 | 0.925 | 0.057 | 0.051 | 0.045 | 0.057 | 579.31 |

| χ2 | DF | χ2/DF | RMSEA (CI) | CFI | IFI | SRMS | Comparisons | Δ RMSEA | Δ CFI | Δ SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configural invariance | 963.13 | 591 | 1.63 | 0.034 (0.030–0.038) | 0.914 | 0.916 | 0.084 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Metric invariance | 1008.80 | 627 | 1.61 | 0.034 (0.030–0.038) | 0.912 | 0.913 | 0.091 | Configural vs. metric | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.007 |

| Scalar invariance | 1035.26 | 647 | 1.60 | 0.034 (0.030–0.037) | 0.911 | 0.911 | 0.095 | Metric vs. scalar | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.004 |

| Error variance invariance | 1195.64 | 703 | 1.70 | 0.036 (0.033–0.040) | 0.887 | 0.886 | 0.093 | Scalar vs. error variance | 0.002 | 0.024 | 0.002 |

| Pearson’s Correlations | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | α | ω | CR | AVE | Mean (SD) | |

| 1. Cognitive emotional impairment | 0.68 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.87 | 0.46 | 1.64 (0.56) | |||

| 2. Behavioral engagement | 0.324 ** | 0.63 | 0.66 | 0.65 | 0.79 | 0.40 | 3.71 (0.59) | ||

| 3. Personal experience with climate change | 0.481 ** | 0.408 ** | 0.83 | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.87 | 0.69 | 1.05 (0.41) | |

| 4. Functional impairment | 0.651 ** | 0.262 ** | 0.487 ** | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.90 | 0.64 | 1.53 (0.62) |

| χ2 | DF | χ2/DF | RMSEA (CI) | CFI | IFI | SRMS | Comparisons | Δ RMSEA | Δ CFI | Δ SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configural invariance | 112.62 | 51 | 2.21 | 0.048 (0.036–0.060) | 0.980 | 0.980 | 0.060 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Metric invariance | 159.88 | 61 | 2.62 | 0.055 (0.045–0.066) | 0.967 | 0.968 | 0.105 | Configural vs. metric | 0.007 | 0.013 | 0.045 |

| Scalar invariance | 186.08 | 65 | 2.86 | 0.059 (0.049–0.069) | 0.960 | 0.960 | 0.104 | Metric vs. scalar | 0.004 | 0.007 | 0.001 |

| Error variance invariance | 200.55 | 67 | 2.99 | 0.061 (0.052–0.071) | 0.956 | 0.956 | 0.085 | Scalar vs. error variance | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.019 |

| Pearson’s Correlations | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | α | ω | CR | AVE | Mean (SD) | |

| 1. Total | 0.75 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.57 | 6.52 (0.70) | |||

| 2. Reality | 0.688 ** | 0.86 | 0.62 | a | 0.85 | 0.74 | 6.63 (0.82) | ||

| 3. Causes | 0.873 ** | 0.369 ** | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.89 | 6.33 (0.99) | |

| 4. Consequences | 0.856 ** | 0.504 ** | 0.598 ** | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.92 | 0.80 | 6.64 (0.72) |

| RMSEA CI90% | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | DF | χ2/DF | IFI | TLI | CFI | GFI | SRMS | RMSEA | LO90 | HI90 | AIC | |

| One factor, 8 items | 166.38 | 20 | 8.32 | 0.911 | 0.875 | 0.911 | 0.922 | 0.053 | 0.117 | 0.101 | 0.134 | 198.38 |

| One factor, 8 items, three correlations between errors | 53.68 | 17 | 3.16 | 0.978 | 0.963 | 0.978 | 0.975 | 0.030 | 0.064 | 0.045 | 0.083 | 91.68 |

| χ2 | DF | χ2/DF | RMSEA (CI) | CFI | IFI | SRMS | Comparisons | Δ RMSEA | Δ CFI | Δ SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configural invariance | 114.82 | 51 | 2.25 | 0.048 (0.037–0.060) | 0.962 | 0.962 | 0.041 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Metric invariance | 121.87 | 65 | 1.88 | 0.041 (0.029–0.052) | 0.966 | 0.966 | 0.045 | Configural vs. metric | 0.007 | 0.004 | 0.003 |

| Scalar invariance | 123.88 | 67 | 1.85 | 0.040 (0.029–0.051) | 0.966 | 0.966 | 0.045 | Metric vs. scalar | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Error variance invariance | 146.84 | 89 | 1.65 | 0.035 (0.025–0.045) | 0.965 | 0.965 | 0.054 | Scalar vs. error variance | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.009 |

| χ2 | DF | χ2/DF | RMSEA (CI) | CFI | IFI | SRMS | Comparisons | Δ RMSEA | Δ CFI | Δ SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configural invariance | 8.10 | 6 | 1.35 | 0.026 (0.000–0.066) | 0.996 | 0.996 | 0.029 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Metric invariance | 8.86 | 10 | 0.89 | 0.000 (0.000–0.043) | 1.000 | 1.002 | 0.032 | Configural vs. metric | 0.026 | 0.004 | 0.003 |

| Scalar invariance | 11.76 | 12 | 0.98 | 0.000 (0.000–0.043) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.037 | Metric vs. scalar | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.005 |

| Error variance invariance | 28.46 | 22 | 1.29 | 0.023 (0.000–0.043) | 0.989 | 0.989 | 0.037 | Scalar vs. error variance | 0.023 | 0.011 | 0.000 |

| Household Behavior | Information-Seeking Behavior | Transportation Choice | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | EP B | β | B | EP B | β | B | EP B | β | |

| Age | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.072 | 0.009 | 0.005 | 0.097 | |||

| Gender | 0.253 | 0.084 | 0.108 | ||||||

| Marital status | −0.240 | 0.121 | −0.123 | ||||||

| Children | 0.291 | 0.135 | 0.102 | 0.360 | 0.161 | 0.138 | |||

| CCAS behavioral engagement | 0.669 | 0.039 | 0.598 | 0.480 | 0.068 | 0.281 | 0.284 | 0.067 | 0.183 |

| CCAS personal experience with climate change | 0.347 | 0.103 | 0.139 | ||||||

| CCAS functional impairment | 0.493 | 0.064 | 0.301 | 0.239 | 0.064 | 0.160 | |||

| CCHS total | 0.071 | 0.030 | 0.088 | ||||||

| R2 (R2 Adj.) | 0.366 (0.364) | 0.403 (0.395) | 0.082 (0.076) | ||||||

| F for change in R2 | 300.339 ** | 75.167 ** | 21.066 ** | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leite, Â.; Lopes, D.; Pereira, L. Pro-Environmental Behavior and Climate Change Anxiety, Perception, Hope, and Despair According to Political Orientation. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 966. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13120966

Leite Â, Lopes D, Pereira L. Pro-Environmental Behavior and Climate Change Anxiety, Perception, Hope, and Despair According to Political Orientation. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(12):966. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13120966

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeite, Ângela, Diana Lopes, and Linda Pereira. 2023. "Pro-Environmental Behavior and Climate Change Anxiety, Perception, Hope, and Despair According to Political Orientation" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 12: 966. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13120966

APA StyleLeite, Â., Lopes, D., & Pereira, L. (2023). Pro-Environmental Behavior and Climate Change Anxiety, Perception, Hope, and Despair According to Political Orientation. Behavioral Sciences, 13(12), 966. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13120966