How Trait Gratitude Influences Adolescent Subjective Well-Being? Parallel–Serial Mediating Effects of Meaning in Life and Self-Control

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Biases

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

3.3. Hypothesis Testing

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Assessing subjective well-being: Progress and opportunities. Soc. Indic. Res. 1994, 31, 103–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Wirtz, D.; Tov, W.; Kim-Prieto, C.; Choi, D.; Oishi, S.; Biswas-Diener, R. New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 97, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbaria, Q.; Bdier, D. The role of social support and subjective well-being as predictors of internet addiction among Israeli-Palestinian college students in Israel. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 19, 1889–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, R.A.; Anstey, K.J.; Windsor, T.D. Subjective well-being mediates the effects of resilience and mastery on depression and anxiety in a large community sample of young and middle-aged adults. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2011, 45, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Xiang, R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Yu, S.; Liu, X. Counting blessings and sharing gratitude in a Chinese prisoner sample: Effects of gratitude-based interventions on subjective well-being and aggression. J. Posit. Psychol. 2019, 14, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, N.M.; Fincham, F.D.; Stillman, T.F.; Dean, L.R. More gratitude, less materialism: The mediating role of life satisfaction. J. Posit. Psychol. 2009, 4, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.K.; Tunney, R.J.; Ferguson, E. Does gratitude enhance prosociality? A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-C. A higher-order gratitude uniquely predicts subjective well-being: Incremental validity above the personality and a single gratitude. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 119, 909–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.M.; Froh, J.J.; Geraghty, A.W. Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 890–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Guardia, J.G.; Ryan, R.M.; Couchman, C.E.; Deci, E.L. Within-person variation in security of attachment: A self-determination theory perspective on attachment, need fulfillment, and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bono, G.; Duffy, T.; Moreno, S. Gratitude in School: Benefits to Students and Schools. In Handbook of Positive Psychology in Schools; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 118–134. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, F.; Yang, K.; Yan, W.; Li, X. How does trait gratitude relate to subjective well-being in Chinese adolescents? The mediating role of resilience and social support. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 1611–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. College students’ trait gratitude and subjective well-being mediated by basic psychological needs. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2020, 48, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unanue, W.; Gomez Mella, M.E.; Cortez, D.A.; Bravo, D.; Araya-Véliz, C.; Unanue, J.; Van Den Broeck, A. The reciprocal relationship between gratitude and life satisfaction: Evidence from two longitudinal field studies. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Yan, W.; Jia, N.; Wang, Q.; Kong, F. Longitudinal relationship between trait gratitude and subjective well-being in adolescents: Evidence from the bi-factor model. J. Posit. Psychol. 2021, 16, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, P.C.; Emmons, R.A.; McCullough, M.E. Gratitude and Subjective Well-Being. In Scientific Concepts Behind Happiness, Kindness, and Empathy in Contemporary Society; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2004; pp. 167–192. [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. The Promise of Adolescence: Realizing Opportunity for All Youth; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Mishra, A.; Breen, W.E.; Froh, J.J. Gender differences in gratitude: Examining appraisals, narratives, the willingness to express emotions, and changes in psychological needs. J. Pers. 2009, 77, 691–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steger, M.F. Meaning in Life. In The Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology; Lopez, S.J., Snyder, C.R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 679–687. ISBN 978-0-19-518724-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman, E.M.; Adams, L.M.; Kashdan, T.B.; Riskind, J.H. Gratitude and grit indirectly reduce risk of suicidal ideations by enhancing meaning in life: Evidence for a mediated moderation model. J. Res. Personal. 2013, 47, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, L.; Liu, H. Gratitude and the meaning of life-the multiple mediating modes of perceived social support and sense of belonging. Chin. J. Spec. Educ. 2016, 197, 79–83+96. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney, J.P.; Baumeister, R.F.; Boone, A.L. High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. J. Pers. 2004, 72, 271–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, T.; Sapmaz, F.; Tel, F.D.; Sapmaz, S.; Temizel, S. Meaning in life and subjective well-being among Turkish university students. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 55, 612–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; He, M.; Li, J. The relationship between meaning in life and subjective well-being in China: A meta-analysis. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 24, 1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Oishi, S.; Kashdan, T.B. Meaning in life across the life span: Levels and correlates of meaning in life from emerging adulthood to older adulthood. J. Posit. Psychol. 2009, 4, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datu, J.A.D.; Mateo, N.J. Gratitude and life satisfaction among Filipino adolescents: The mediating role of meaning in life. Int. J. Adv. Couns. 2015, 37, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E. Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.-B.; Dou, K.; Liang, Y. The relationship between presence of meaning, search for meaning, and subjective well-being: A three-level meta-analysis based on the meaning in life questionnaire. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 467–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.T. Meaning Management Theory and Death Acceptance. In Existential and Spiritual Issues in Death Attitudes; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2008; pp. 65–87. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.-F.; Zhang, W.; Li, D.-P.; Xiao, J.-T. Gratitude and its relationship with well-being. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 18, 1110. [Google Scholar]

- De Ridder, D.T.; Lensvelt-Mulders, G.; Finkenauer, C.; Stok, F.M.; Baumeister, R.F. Taking stock of self-control: A meta-analysis of how trait self-control relates to a wide range of behaviors. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 16, 76–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickens, L.; DeSteno, D. The grateful are patient: Heightened daily gratitude is associated with attenuated temporal discounting. Emotion 2016, 16, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, T.T.; Gillebaart, M.; Kroese, F.; De Ridder, D. Why are people with high self-control happier? The effect of trait self-control on happiness as mediated by regulatory focus. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galla, B.M.; Duckworth, A.L. More than resisting temptation: Beneficial habits mediate the relationship between self-control and positive life outcomes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 109, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, W.; Luhmann, M.; Fisher, R.R.; Vohs, K.D.; Baumeister, R.F. Yes, but are they happy? Effects of trait self-control on affective well-being and life satisfaction. J. Pers. 2014, 82, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Branigan, C. Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cogn. Emot. 2005, 19, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Guo, Y. Perceived control in the social context. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 20, 1860–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yek, M.H.; Olendzki, N.; Kekecs, Z.; Patterson, V.; Elkins, G. Presence of meaning in life and search for meaning in life and relationship to health anxiety. Psychol. Rep. 2017, 120, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mischel, W.; Shoda, Y. A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: Reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychol. Rev. 1995, 102, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-B.; Salcuni, S.; Delvecchio, E. Meaning in life, self-control and psychological distress among adolescents: A cross-national study. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 272, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamir, M.; Mauss, I.B. Social Cognitive Factors in Emotion Regulation: Implications for Well-Being. In Emotion Regulation and Well-Being; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Schnell, T.; Krampe, H. Meaning in life and self-control buffer stress in times of COVID-19: Moderating and mediating effects with regard to mental distress. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-B.; Willems, Y.E.; Stok, F.M.; Deković, M.; Bartels, M.; Finkenauer, C. Parenting and self-control across early to late adolescence: A three-level meta-analysis. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 14, 967–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Qin, J.; Huang, W. Self-control mediates the relationship between the meaning in life and the mobile phone addiction tendency of Chinese college students. Stud. Psychol. Behav. 2019, 17, 536. [Google Scholar]

- Hedlund, D.E. Personal Meaning: The Problem of Educating for Wisdom. Pers. Guid. J. 1977, 55, 602–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, M.J.; Baumeister, R.F. Meaning in Life: Nature, Needs, and Myths. In Meaning in Positive Existential Psychology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Zhang, W.; Zeng, Y.; Ye, T.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z. Relationship between adolescents’ gratitude and problem behavior: The mediating role of school connectedness. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2011, 27, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, M.E.; Emmons, R.A.; Tsang, J.-A. The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Psychometric evaluation of the meaning in life questionnaire in Chinese middle school students. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 21, 763–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lu, J. The compilation of the middle school students’ self-control ability questionnaire. J. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 27, 1477–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.D.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Huang, S.; Wu, Q. Relationship between academic self-efficacy and Internet gaming disorder of college students: Mediating effect of subjective well-being. China J. Health Psychol. 2022, 30, 718–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, G.; Zhang, L.; Deng, J.; Yin, H. Bullying victimization and suicidal ideation among adolescents: The mediating role of psychological suzhi and the moderating role of perceived school climate. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 42, 17454–17464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Zhang, L.; Cao, G.; Yin, H. Effects of adolescent academic stress on sleep quality: Mediating effect of negative affect and moderating role of peer relationships. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 4381–4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, R.A.; Stern, R. Gratitude as a psychotherapeutic intervention. J. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 69, 846–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buddelmeyer, H.; Powdthavee, N. Can having internal locus of control insure against negative shocks? Psychological evidence from panel data. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2016, 122, 88–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.A.; Edwards, M.E.; Grandgenett, H.M.; Scherer, L.L.; DiLillo, D.; Jaffe, A.E. Does gratitude promote resilience during a pandemic? An examination of mental health and positivity at the onset of COVID-19. J. Happiness Stud. 2022, 23, 3463–3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szcześniak, M.; Rodzeń, W.; Malinowska, A.; Kroplewski, Z. Big five personality traits and gratitude: The role of emotional intelligence. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2020, 13, 977–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmons, R.A.; Mishra, A. Why gratitude enhances well-being: What we know, what we need to know. Des. Posit. Psychol. Tak. Stock Mov. Forw. 2011, 248, 262. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.T. Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Can. Psychol. Can. 2011, 52, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srirangarajan, T.; Oshio, A.; Yamaguchi, A.; Akutsu, S. Cross-cultural Nomological network of gratitude: Findings from midlife in the United States (MIDUS) and Japan (MIDJA). Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-C.; Yeh, Y. How gratitude influences well-being: A structural equation modeling approach. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 118, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Ding, K.; Zhao, J. The relationships among gratitude, self-esteem, social support and life satisfaction among undergraduate students. J. Happiness Stud. 2015, 16, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, P.C. Gratitude and The Good Life: Toward a Psychology of Appreciation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Sang, Z.; Chan, D.K.-S.; Teng, F.; Liu, M.; Yu, S.; Tian, Y. Sources of meaning in life among Chinese university students. J. Happiness Stud. 2016, 17, 1473–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazeou-Nieuwenhuis, A.; Orehek, E.; Scheier, M.F. The meaning of action: Do self-regulatory processes contribute to a purposeful life? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 116, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A.L.; Grant, H.; Loew, B.; Oettingen, G.; Gollwitzer, P.M. Self-regulation strategies improve self-discipline in adolescents: Benefits of mental contrasting and implementation intentions. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Ma, C. The effect of trait anxiety on academic achievement of middle school students: The mediating role of meaning in life and self-control. Chin. J. Spec. Educ. 2021, 85, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Tugade, M.M.; Fredrickson, B.L.; Feldman Barrett, L. Psychological resilience and positive emotional granularity: Examining the benefits of positive emotions on coping and health. J. Pers. 2004, 72, 1161–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulhus, D.L. Two-component models of socially desirable responding. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 46, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Chen, S.; Chen, Y.; Li, D.; Yin, H. The impact of peer victimization on Chinese left-behind adolescent suicidal ideation: The mediating role of psychological suzhi and the moderating role of family cohesion. Child Abuse Negl. 2023, 141, 106235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Trait gratitude | 30.49 | 5.94 | 1 | ||||

| 2. Presence of meaning | 20.20 | 6.42 | 0.331 *** | 1 | |||

| 3. Search for meaning | 24.36 | 6.03 | 0.333 *** | 0.348 *** | 1 | ||

| 4. Self-control | 111.99 | 20.46 | 0.194 *** | 0.424 *** | 0.260 *** | 1 | |

| 5. Subjective well-being | 20.35 | 7.08 | 0.284 *** | 0.402 *** | 0.205 *** | 0.332 *** | 1 |

| Predictor Variables | Stage 1: SWB | Stage 2: Presence of Meaning | Stage 3: Search for Meaning | Stage 4: Self-Control | Stage 5: SWB | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | |

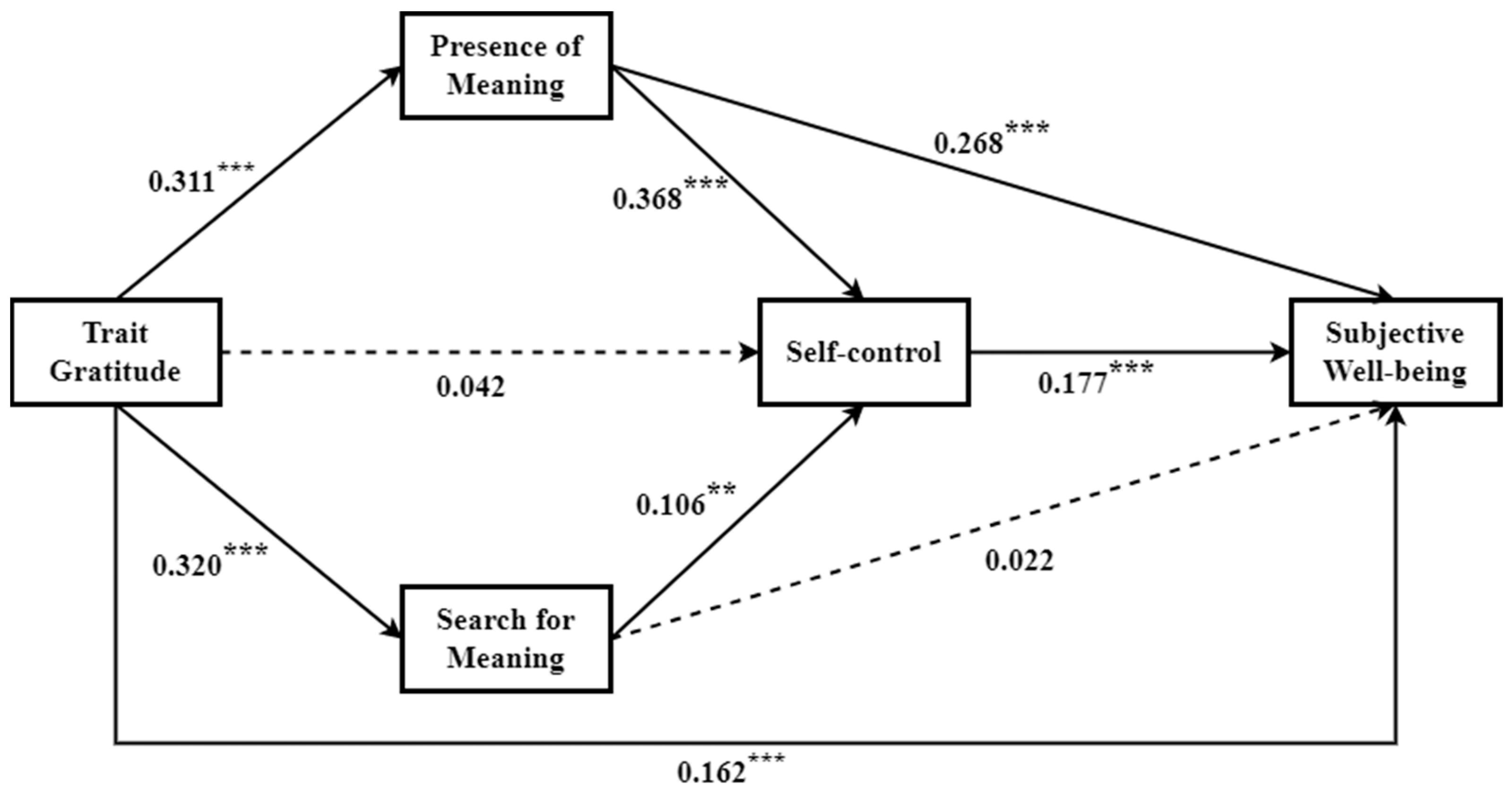

| Trait gratitude | 0.284 | 7.850 *** | 0.311 | 8.164 *** | 0.320 | 8.401 *** | 0.042 | 1.066 | 0.162 | 4.162 *** |

| Presence of meaning | 0.368 | 9.130 *** | 0.268 | 6.210 *** | ||||||

| Search for meaning | 0.106 | 2.626 ** | 0.022 | 0.551 | ||||||

| Self-control | 0.177 | 4.315 *** | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.080 | 0.100 | 0.105 | 0.189 | 0.212 | |||||

| F | 61.624 *** | 66.653 *** | 70.580 *** | 46.290 *** | 40.040 *** | |||||

| Effect | Boot SE | 95% CI | Relative Mediating Effects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total indirect effects | 0.124 | 0.023 | [0.081, 0.172] a | 43.32% |

| Trait gratitude → Presence of meaning → SWB | 0.083 | 0.018 | [0.050, 0.121] a | 29.08% |

| Trait gratitude → Search for meaning → SWB | 0.007 | 0.015 | [−0.023, 0.037] | |

| Trait gratitude → Self-control → SWB | 0.007 | 0.008 | [−0.007, 0.025] | |

| Trait gratitude → Presence of meaning → Self-control → SWB | 0.020 | 0.006 | [0.010, 0.034] a | 7.05% |

| Trait gratitude → Search for meaning → Self-control → SWB | 0.006 | 0.003 | [0.009, 0.013] a | 2.09% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, D.; Yin, H. How Trait Gratitude Influences Adolescent Subjective Well-Being? Parallel–Serial Mediating Effects of Meaning in Life and Self-Control. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 902. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110902

Li Y, Liu S, Li D, Yin H. How Trait Gratitude Influences Adolescent Subjective Well-Being? Parallel–Serial Mediating Effects of Meaning in Life and Self-Control. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(11):902. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110902

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yulin, Sige Liu, Dan Li, and Huazhan Yin. 2023. "How Trait Gratitude Influences Adolescent Subjective Well-Being? Parallel–Serial Mediating Effects of Meaning in Life and Self-Control" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 11: 902. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110902

APA StyleLi, Y., Liu, S., Li, D., & Yin, H. (2023). How Trait Gratitude Influences Adolescent Subjective Well-Being? Parallel–Serial Mediating Effects of Meaning in Life and Self-Control. Behavioral Sciences, 13(11), 902. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110902