Latent Class Analysis on Types of Challenging Behavior in Persons with Developmental Disabilities: Focusing on Factors Affecting the Types of Challenging Behavior

Abstract

:1. Introduction

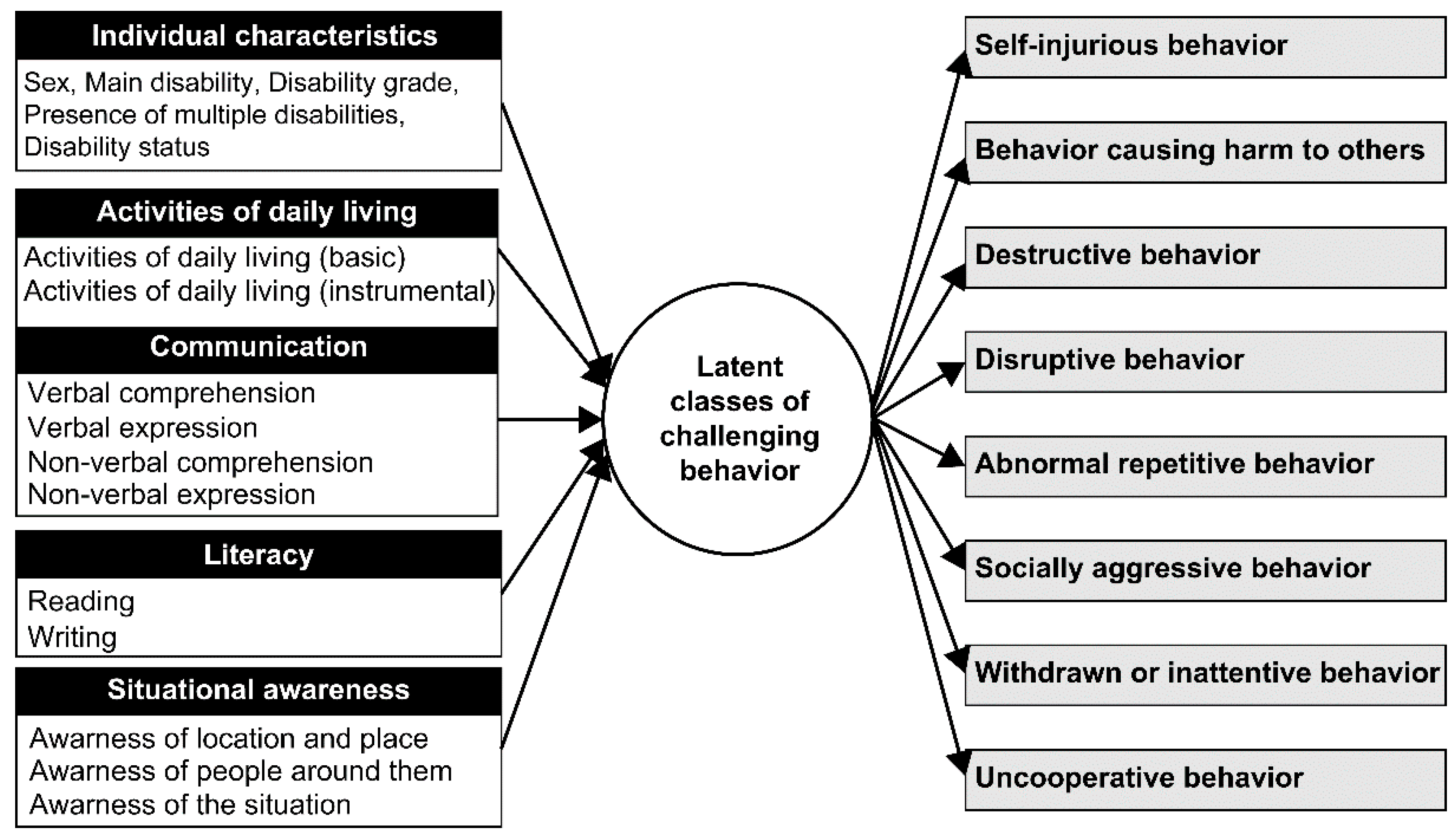

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Participants

2.2. Measurement Tool

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

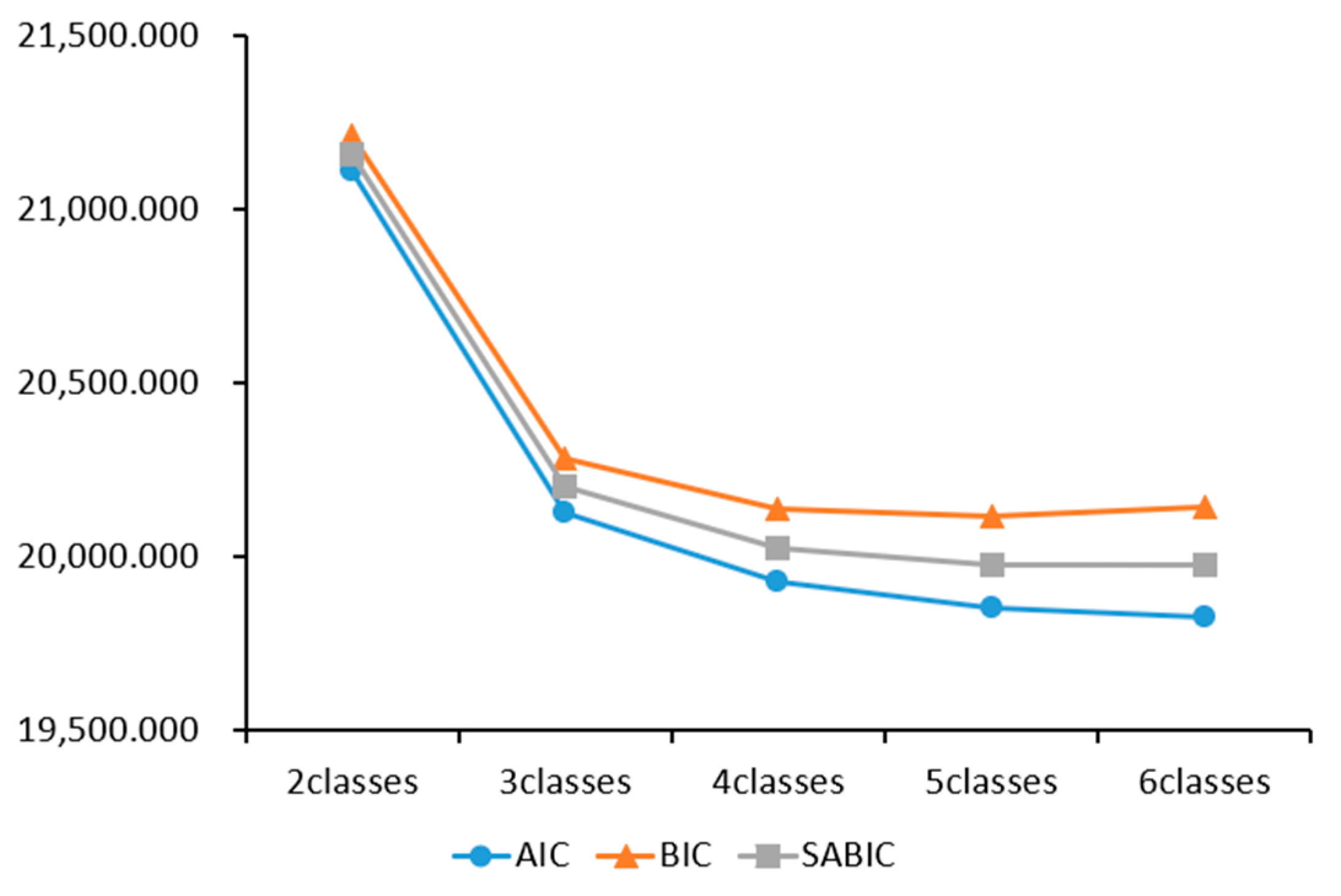

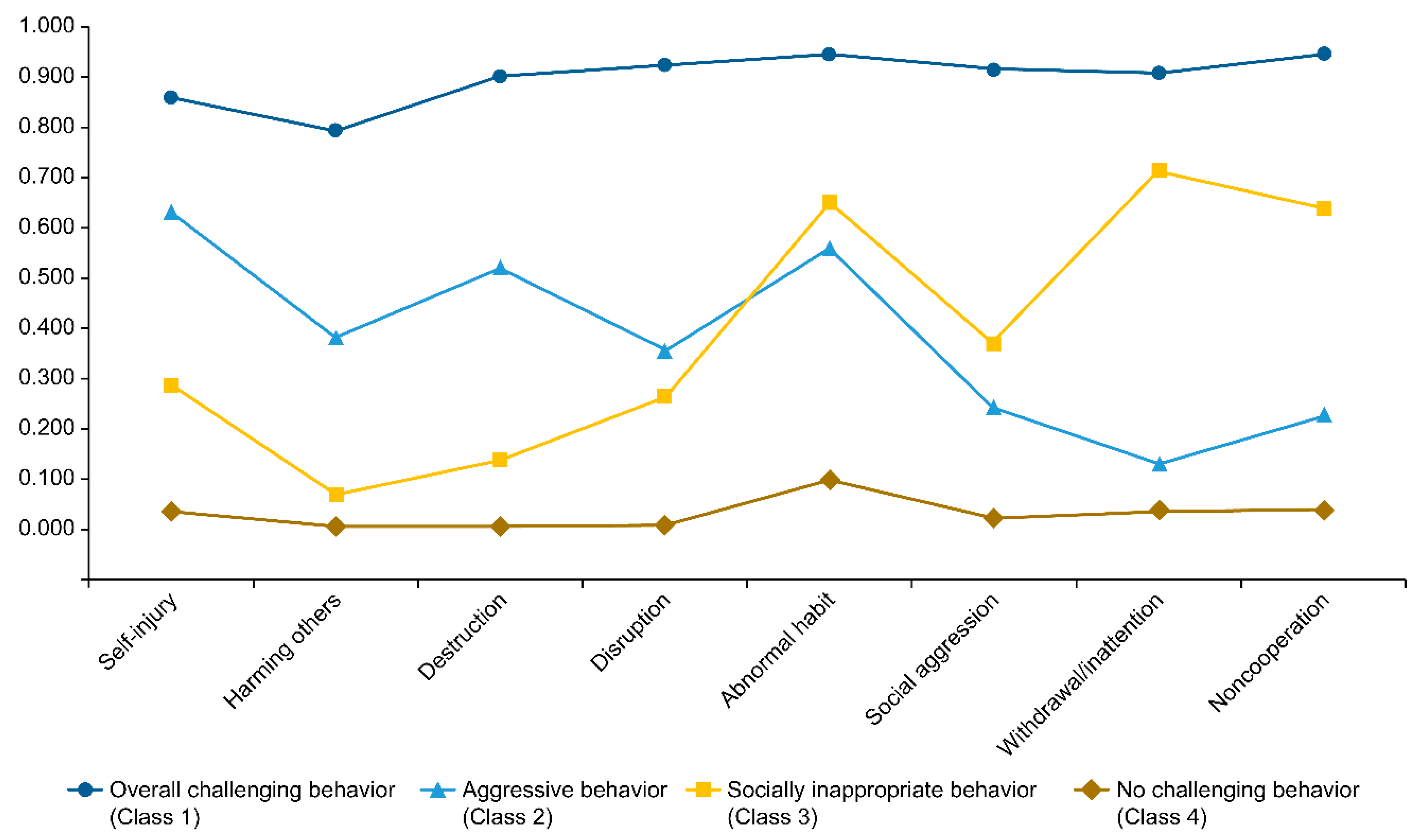

3.1. Latent Class Analysis According to the Types of Challenging Behavior

3.2. Analysis of Factors Affecting Classification

4. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Emerson, E. Challenging Behaviour: Analysis and Intervention in Persons with Learning Difficulties; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Matson, J.L.; Mahan, S.; Hess, J.A.; Fodstad, J.C.; Neal, D. Progression of challenging behaviors in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders as measured by the Autism Spectrum Disorders-Problem Behaviors for Children (ASD-PBC). Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2010, 4, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doehring, P.; Reichow, B.; Palka, T.; Phillips, C.; Hagopian, L. Behavioral approaches to managing severe problem behaviors in children with autism spectrum and related developmental disorders: A descriptive analysis. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 23, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matson, J.L.; Wilkins, J.; Macken, J. The relationship of challenging behaviors to severity and symptoms of autism spectrum disorders. J. Ment. Health Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2008, 2, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, R.H.; Carr, E.G.; Strain, P.S.; Todd, A.W.; Reed, H.K. Problem behavior interventions for young children with autism: A research synthesis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2002, 32, 423–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, E.; Kiernan, C.; Alborz, A.; Reeves, D.; Mason, H.; Swarbrick, R.; Mason, L.; Hatton, C. The prevalence of challenging behaviors: A total population study. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2001, 22, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowring, D.L.; Painter, J.; Hastings, R.P. Prevalence of challenging behaviour in adults with intellectual disabilities, correlates, and association with mental health. Curr. Dev. Disord. Rep. 2019, 6, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougal, J.; Hiralall, A.S. Bridging research into practice to intervene with young aggressive students in the public school setting: Evaluation of the behavior consultation team (BCT) Project. In Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the National Association of School Psychologists, Orlando, FL, USA, 14–18 April 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Saloviita, T. Challenging behaviour, and staff responses to it, in residential environments for people with intellectual disability in Finland. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2002, 27, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.; Pear, J. Behavior Modification: What It Is and How to Do It, 9th ed.; Pearson Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman, J.M. Characteristic of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders of Children and Youth, 10th ed.; Pearson Education: Cranberry, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bambara, L.M.; Kern, L. Individualized Supports for Students with Problem Behaviors: Designing Positive Behavior Plans; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wendeler, J. Geistige Behinderung; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Brimer, R.W. Students with Severe Disabilities: Current Perspectives and Practices; Mayfield Publishing Co.: Mountain View, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 2021 Survey on Persons with Developmental Disabilities. Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare. Available online: https://www.mohw.go.kr/react/al/sal0301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=04&MENU_ID=0403&page=1&CONT_SEQ=372831 (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Holden, B.; Gitlesen, J.P. A total population study of challenging behaviour in the county of Hedmark, Norway: Prevalence, and risk markers. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2006, 27, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, B.A.; Dorsey, M.F.; Slifer, K.J.; Bauman, K.E.; Richman, G.S. Toward a functional analysis of self-injury. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1994, 27, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, C.H.; Richman, D.M. Preventing challenging behaviors in people with neurodevelopmental disabilities. Curr. Dev. Disord. Rep. 2019, 6, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didden, R.; Sturmey, P.; Sigafoos, J.; Lang, R.; O’Reilly, M.F.; Lancioni, G.E. Nature, prevalence, and characteristics of challenging behavior. In Functional Assessment for Challenging Behaviors; Matson, J.L., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, O.; Healy, O.; Leader, G. Risk factors for challenging behaviors among 157 children with autism spectrum disorder in Ireland. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2009, 3, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, K.; Hall, S.; Oliver, C. Risk markers associated with challenging behaviours in people with intellectual disabilities: A meta-analytic study. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2003, 47, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, G.H.; Beadle-Brown, J.; Wing, L.; Gould, J.; Shah, A.; Holmes, N. Chronicity of challenging behaviors in people with severe intellectual disabilities and/or autism: A total population sample. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2005, 35, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, J.M.; Foxx, R.M.; Jacobson, J.W.; Green, G.; Mulick, J.A. Positive behavior support and applied behavior analysis. Behav. Anal. 2006, 29, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, G.P.; Iwata, B.A.; McCord, B.E. Functional analysis of problem behavior: A review. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2003, 36, 147–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.H.; Bodfish, J.W. Repetitive behavior disorders in autism. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 1998, 4, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, D.R.; Horner, R.H. Adding functional behavioral assessment to first step to success: A case study. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 2007, 9, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, B.O. Handbook of Quantitative Methodology for the Social Science; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1974, 19, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, G. Estimating dimensions of a model. Ann. Stat. 1978, 6, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sclove, S.L. Application of model-selection criteria to some problems analysis. Psychometrika 1987, 52, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, G.J.; Peel, D. Finite Mixture Models; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, Y.; Mendell, N.R.; Rubin, D.B. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika 2001, 88, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asparouhov, T.; Muthén, B. Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using M plus. Struct. Equ. Model. 2014, 21, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagin, D.S. Group-Based Modeling of Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrbakk, E.; von Tetzchner, S. Psychiatric disorders and behavior problems in people with intellectual disability. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2008, 29, 316–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matson, J.L.; Wilkins, J. Factors associated with the questions about behavior function for functional assessment of low and high rate challenging behaviors in adults with intellectual disability. Behav. Modif. 2009, 33, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, D.R.; Garcia, M.J.; Granpeesheh, D.; Tarbox, J. Differential diagnosis in autism spectrum disorders. In Applied Behavior Analysis for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A handbook; Matson, J.L., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, 2010; pp. 83–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, L.; Cheung Chung, M.; Jenner, L. Preliminary findings on communication and challenging behaviour in learning difficulty. Br. J. Dev. Disabil. 1993, 39, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, K.; Allen, D.; Jones, E.; Brophy, S.; Moore, K.; James, W. Challenging behaviours: Prevalence and topographies. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2007, 51, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totsika, V.; Toogood, S.; Hastings, R.P.; Lewis, S. Persistence of challenging behaviours in adults with intellectual disability over a period of 11 years. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2008, 52, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, M.P.; Brody, E.M. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969, 9, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S. Assessing self-maintenance: Activities of daily living, mobility, and instrumental activities of daily living. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1983, 31, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, C. The Lawton instrumental activities of daily living scale. Am. J. Nurs. 2008, 108, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, A.D.; Vogel, A.; Becker, T.; Salize, H.J.; Voss, E.; Werner, A.; Arnold, K.; Schützwohl, M. Proxy and self-reported Quality of Life in adults with intellectual disabilities: Impact of psychiatric symptoms, problem behaviour, psychotropic medication and unmet needs. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 45, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Classification | Variable Name | Variable Content | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of challenging behavior | Self-injurious behavior (self-injury) | 0 = No, 1 = Yes | |

| Behavior causing harm to others (harming others) | |||

| Destructive behavior (destruction) | |||

| Disruptive behavior (disruption) | |||

| Abnormal repetitive behavior (abnormal habit) | |||

| Socially aggressive behavior (social aggression) | |||

| Withdrawn or inattentive behavior (withdrawal/inattention) | |||

| Uncooperative behavior (noncooperation) | |||

| Determinant | Individual characteristics | Sex | 0 = Female, 1 = Male |

| Main disability | 0 = intellectual disabilities, 1 = ASD | ||

| Disability grade | 0 = Grade 1, 1 = Grade 2, 2 = Grade 3 | ||

| Presence of multiple disabilities | 0 = Without multiple disabilities 1 = With multiple disabilities | ||

| Disability status | 1 = Gradually improving 2 = Not improving or deteriorating 3 = Gradually deteriorating | ||

| Activities of daily living | Changing clothes, washing face/brushing teeth/washing hair, taking a bath, eating when served, walking, defecating and urinating | The mean of six items on activities of daily living 1 = Totally dependent 2 = Substantially dependent 3 = Partially dependent 4 = Independent | |

| Cleaning, preparing meals, doing the laundry | The mean of three items on activities of daily living 1 = Totally dependent 2 = Substantially dependent 3 = Partially dependent 4 = Independent | ||

| Going out to somewhere nearby, using public transportation, purchasing things, managing money, using a phone, taking medication | The mean of six items on activities of daily living 1 = Totally dependent 2 = Substantially dependent 3 = Partially dependent 4 = Independent | ||

| Communication | Understanding what others say | 1 = Can understand two or more sentences 2 = Can understand a simple sentence 3 = Can understand words only 4 = Can barely understand others | |

| Expressing opinions verbally | 1 = Expressing opinions in at least two words or in sentences 2 = Expressing opinions using clear words 3 = Expressing opinions using unclear words 4 = Expressing opinions making unclear sounds 5 = Cannot express any opinion with sounds at all | ||

| Understanding nonverbal expressions | 1 = Can understand 2 = Can understand on a limited basis 3 = Cannot understand | ||

| Using nonverbal expressions | 1 = Can use 2 = Can use on a limited basis 3 = Cannot use | ||

| Literacy | Reading | 1 = Impossible, 2 = Possible on a limited basis, 3 = Possible | |

| Writing | 1 = Impossible, 2 = Possible on a limited basis, 3 = Possible | ||

| Situational awareness | Awareness of location and place Awareness of people around them Awareness of the situation | The mean of three items concerning cognitive ability 1 = Totally dependent 2 = Substantially dependent 3 = Partially dependent 4 = Independent | |

| Two Classes | Three Classes | Four Classes | Five Classes | Six Classes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information index | AIC | 21,110.815 | 20,128.954 | 19,927.179 | 19,850.558 | 19,825.809 |

| BIC | 21,212.867 | 20,285.033 | 20,137.285 | 20,114.692 | 20,143.970 | |

| SABIC | 21,158.851 | 20,202.421 | 20,026.077 | 19,974.887 | 19,975.568 | |

| Quality of classification | Entropy | 0.895 | 0.830 | 0.806 | 0.758 | 0.755 |

| Validation of model comparison | LMRLRT | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.039 |

| BLRT | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Classification rate | Class 1 | 0.311 | 0.330 | 0.164 | 0.170 | 0.123 |

| Class 2 | 0.069 | 0.510 | 0.109 | 0.126 | 0.027 | |

| Class 3 | 0.160 | 0.517 | 0.133 | 0.437 | ||

| Class 4 | 0.209 | 0.115 | 0.124 | |||

| Class 5 | 0.456 | 0.139 | ||||

| Class 6 | 0.150 | |||||

| Class 1 | Class 2 | Class 3 | Class 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probability that the behavior would belong to Class 1 | 0.933 | 0.023 | 0.044 | 0.000 |

| Probability that the behavior would belong to Class 2 | 0.038 | 0.772 | 0.147 | 0.043 |

| Probability that the behavior would belong to Class 3 | 0.024 | 0.089 | 0.838 | 0.048 |

| Probability that the behavior would belong to Class 4 | 0.000 | 0.022 | 0.032 | 0.946 |

| Variable | Class 1 | Class 2 | Class 3 | Class 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Challenging Behavior | Aggressive Behavior | Socially Inappropriate Behavior | None | |||||

| Coefficient | Standard Error | Coefficient | Standard Error | Coefficient | Standard Error | Coefficient | Standard Error | |

| Self-injury | 0.858 | 0.020 | 0.631 | 0.049 | 0.286 | 0.039 | 0.036 | 0.007 |

| Harming others | 0.791 | 0.026 | 0.381 | 0.050 | 0.068 | 0.021 | 0.006 | 0.003 |

| Destruction | 0.899 | 0.021 | 0.519 | 0.063 | 0.139 | 0.031 | 0.006 | 0.004 |

| Disruption | 0.922 | 0.017 | 0.355 | 0.051 | 0.263 | 0.031 | 0.007 | 0.003 |

| Abnormal habit | 0.945 | 0.014 | 0.560 | 0.049 | 0.649 | 0.029 | 0.098 | 0.010 |

| Social aggression | 0.914 | 0.018 | 0.241 | 0.043 | 0.369 | 0.028 | 0.021 | 0.005 |

| Withdrawal/inattention | 0.907 | 0.019 | 0.129 | 0.077 | 0.713 | 0.038 | 0.036 | 0.008 |

| Noncooperation | 0.945 | 0.015 | 0.225 | 0.066 | 0.637 | 0.035 | 0.040 | 0.007 |

| Percentage | 16.4% | 11.0% | 20.9% | 51.7% | ||||

| Reference Group | No Challenging Behavior | |||||

| Comparative Group | Socially Inappropriate Behavior | Aggressive Behavior | Overall Challenging Behavior | |||

| Variable | Coefficient | Standard Error | Coefficient | Standard Error | Coefficient | Standard Error |

| Sex | 0.021 | 0.140 | −0.131 | 0.222 | 0.230 | 0.154 |

| Main disability | 0.882 *** | 0.150 | 1.351 *** | 0.206 | 1.713 *** | 0.154 |

| Disability grade | −0.103 | 0.110 | −0.504 ** | 0.171 | −0.462 *** | 0.111 |

| Multiple disabilities | −0.042 | 0.219 | −0.353 | 0.364 | 0.417 * | 0.200 |

| Disability status | 0.164 | 0.116 | −0.152 | 0.162 | 0.519 *** | 0.119 |

| Activities of daily living 1 | 0.464 ** | 0.145 | −0.099 | 0.169 | 0.103 | 0.107 |

| Activities of daily living 2−1 | −0.517 *** | 0.095 | −0.259 | 0.170 | −0.541 *** | 0.098 |

| Activities of daily living 2−2 | −0.047 | 0.115 | −0.082 | 0.200 | −0.153 | 0.115 |

| Verbal comprehension | 0.088 | 0.131 | −0.135 | 0.171 | 0.087 | 0.121 |

| Verbal expression | −0.026 | 0.101 | −0.036 | 0.141 | 0.181 | 0.095 |

| Nonverbal comprehension | 0.175 | 0.173 | 0.269 | 0.275 | −0.198 | 0.167 |

| Nonverbal expression | −0.301 | 0.164 | −0.355 | 0.242 | −0.181 | 0.164 |

| Reading | 0.633 ** | 0.219 | 1.090 ** | 0.340 | 0.891 *** | 0.217 |

| Writing | −0.276 | 0.221 | −0.381 | 0.354 | −0.558 * | 0.218 |

| Situational awareness | −0.609 *** | 0.152 | −0.341 | 0.233 | −0.549 ** | 0.160 |

| Reference Group | Socially Inappropriate Behavior | Aggressive Behavior | ||||

| Comparative Group | Aggressive Behavior | Overall Challenging Behavior | Overall Challenging Behavior | |||

| Variable | Coefficient | Standard Error | Coefficient | Standard Error | Coefficient | Standard Error |

| Sex | −0.153 | 0.262 | 0.209 | 0.181 | 0.362 | 0.243 |

| Main disability | 0.470 | 0.242 | 0.832 *** | 0.175 | 0.362 | 0.227 |

| Disability grade | −0.401 | 0.208 | −0.358 ** | 0.135 | 0.042 | 0.188 |

| Multiple disabilities | −0.311 | 0.420 | 0.459 | 0.246 | 0.770 * | 0.365 |

| Disability status | −0.316 | 0.194 | 0.354 ** | 0.136 | 0.670 *** | 0.177 |

| Activities of daily living 1 | −0.562 * | 0.222 | −0.360 ** | 0.136 | 0.202 | 0.168 |

| Activities of daily living 2-1 | 0.259 | 0.197 | −0.023 | 0.112 | −0.282 | 0.181 |

| Activities of daily living 2-2 | −0.035 | 0.233 | −0.106 | 0.135 | −0.071 | 0.205 |

| Verbal comprehension | −0.223 | 0.203 | −0.001 | 0.140 | 0.221 | 0.177 |

| Verbal expression | −0.010 | 0.162 | 0.207 | 0.108 | 0.217 | 0.141 |

| Nonverbal comprehension | 0.094 | 0.334 | −0.373 | 0.205 | −0.467 | 0.285 |

| Nonverbal expression | −0.054 | 0.297 | 0.120 | 0.202 | 0.174 | 0.260 |

| Reading | 0.457 | 0.403 | 0.259 | 0.252 | −0.199 | 0.360 |

| Writing | −0.104 | 0.425 | −0.281 | 0.256 | −0.177 | 0.380 |

| Situational awareness | 0.268 | 0.275 | 0.060 | 0.190 | −0.208 | 0.247 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, D. Latent Class Analysis on Types of Challenging Behavior in Persons with Developmental Disabilities: Focusing on Factors Affecting the Types of Challenging Behavior. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 879. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110879

Kim D. Latent Class Analysis on Types of Challenging Behavior in Persons with Developmental Disabilities: Focusing on Factors Affecting the Types of Challenging Behavior. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(11):879. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110879

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Daeyong. 2023. "Latent Class Analysis on Types of Challenging Behavior in Persons with Developmental Disabilities: Focusing on Factors Affecting the Types of Challenging Behavior" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 11: 879. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110879

APA StyleKim, D. (2023). Latent Class Analysis on Types of Challenging Behavior in Persons with Developmental Disabilities: Focusing on Factors Affecting the Types of Challenging Behavior. Behavioral Sciences, 13(11), 879. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110879