The Associations between Obsessive Compulsive Personality Traits, Self-Efficacy, and Exercise Addiction

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Framework: Social Cognitive Theory

1.2. Obsessive Compulsive Personality Disorder (OCPD) Traits

1.3. Self-Efficacyche

1.4. The Present Study

- A higher level of OCPD traits will be related to a higher risk of exercise addiction.

- Higher levels of self-efficacy will be related to a higher risk of exercise addiction.

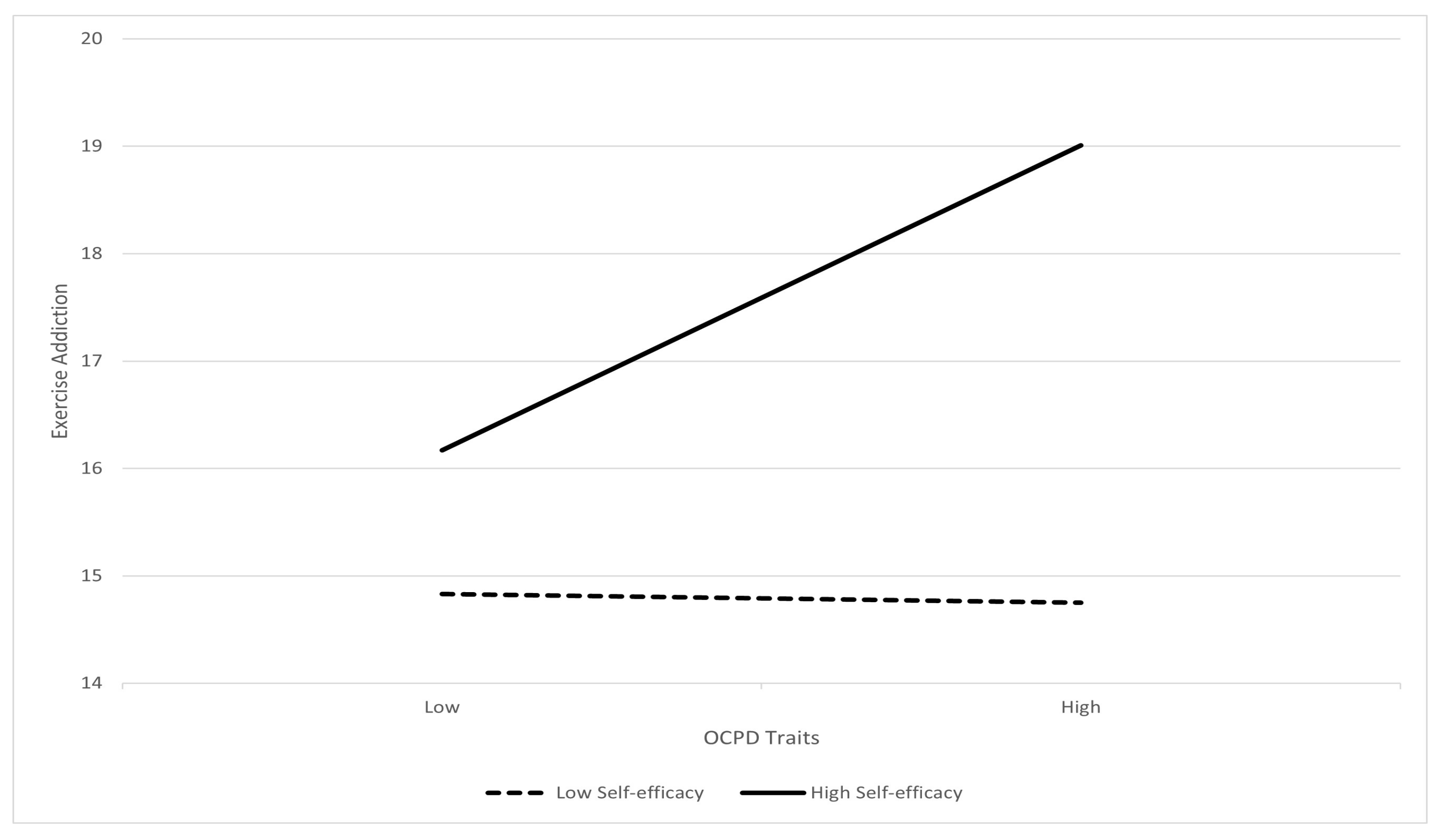

- Self-efficacy will moderate the association between OCPD traits and exercise addiction. In particular, individuals with more OCPD traits and higher self-efficacy will be more vulnerable to exercise addiction compared with individuals with more of OCPD traits but lower self-efficacy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

3.2. Results of Regression Analyses

3.3. Self-Efficacy as a Moderator

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Szabo, A.; Pinto, A.; Griffiths, M.D.; Kovácsik, R.; Demetrovics, Z. The psychometric evaluation of the Revised Exercise Addiction Inventory: Improved psychometric properties by changing item response rating. J. Behav. Addict. 2019, 8, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M.D.; Szabo, A.; Terry, A. The exercise addiction inventory: A new brief screening tool. Addict. Res. Theory 2004, 12, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M.D.; Szabo, A.; Terry, A. The exercise addiction inventory: A quick and easy screening tool for health practitioners. Br. J. Sports Med. 2005, 39, e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laddu, D.R.; Rana, J.S.; Murillo, R.; Sorel, M.E.; Quesenberry, C.P.; Allen, N.B.; Gabriel, K.P.; Carnethon, M.R.; Liu, K.; Reis, J.P.; et al. 25-Year Physical Activity Trajectories and Development of Subclinical Coronary Artery Disease as Measured by Coronary Artery Calcium: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 1660–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landolfi, E. Exercise addiction. Sports Med. 2013, 43, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, A.; Weinstein, Y. Exercise addiction-diagnosis, bio-psychological mechanisms and treatment issues. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 4062–4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symons Downs, D.; MacIntyre, R.I.; Heron, K.E. Exercise addiction and dependence. In APA Handbook of Sport and Exercise Psychology. Exercise Psychology; Anshel, M.H., Petruzzello, S.J., Labbé, E.E., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 589–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, A.A.; Koehmstedt, C.; Kop, W.J. Mental health consequences of exercise withdrawal: A systematic review. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2017, 49, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, M.B.; Nielsen, R.O.; Gudex, C.; Hinze, C.J.; Jørgensen, U. Exercise addiction is associated with emotional distress in injured and non-injured regular exercisers. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2018, 8, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, A.; Maayan, G.; Weinstein, Y. A study on the relationship between compulsive exercise, depression and anxiety. J. Behav. Addict. 2015, 4, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, A.; Szabo, A. Exercise addiction: A narrative overview of research issues. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2023, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trott, M.; Jackson, S.E.; Firth, J.; Fisher, A.; Johnstone, J.; Mistry, A.; Stubbs, B.; Smith, L. Exercise prevalence and correlates in the absence of eating disorder symptomology: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Addict. Med. 2020, 14, e321–e329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR); American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorov, A.Y.; Szabo, A. The exercise paradox: An interactional model for a clearer conceptualization of exercise addiction. J. Behav. Addict. 2013, 2, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, M.; Jackson, S.E.; Firth, J.; Jacob, L.; Grabovac, I.; Mistry, A.; Stubbs, B.; Smith, L. A comparative meta-analysis of the prevalence of exercise addiction in adults with and without indicated eating disorders. Eat. Weight Disord.-Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2021, 26, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausenblas, H.A.; Downs, D.S. How much is too much? The development and validation of the exercise addiction scale. Psychol. Health 2002, 17, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasman, L.; Thompson, J.K. Body image and eating disturbance in obligatory runners, obligatory weightlifters, and sedentary individuals. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1988, 7, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.; Coppolino, P.; Oliva, P. Exercise addiction and maladaptive perfectionism: The mediating role of basic psychological needs. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2016, 14, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.; Hausenblas, H.A.; Oliva, P.; Cuzzocrea, F.; Larcan, R. The role of age, gender, mood states and exercise frequency on exercise addiction. J. Behav. Addict. 2013, 2, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, A.; Peralta, M.; Sarmento, H.; Loureiro, V.; Gouveia, É.R.; Gaspar de Matos, M. Prevalence of Risk for Exercise Addiction: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2019, 49, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, M.B.; Christiansen, E.; Elklit, A.; Bilenberg, N.; Støving, R.K. Exercise addiction: A study of eating disorder symptoms, quality of life, personality traits and attachment styles. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 215, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mónok, K.; Berczik, K.; Urbán, R.; Szabo, A.; Griffiths, M.D.; Farkas, J.; Magi, A.; Eisinger, A.; Kurimay, T.; Kökönyei, G.; et al. Psychometric properties and concurrent validity of two exercise addiction measures: A population wide study. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2012, 13, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yager, Z.; Gray, T.; Curry, C.; McLean, S.A. Body dissatisfaction, excessive exercise, and weight change strategies used by first-year undergraduate students: Comparing health and physical education and other education students. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Griffiths, M.D.; Gjertsen, S.R.; Krossbakken, E.; Kvam, S.; Pallesen, S. The relationships between behavioral addictions and the five-factor model of personality. J. Behav. Addict. 2013, 2, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumitru, D.C.; Dumitru, T.; Maher, A.J. A systematic review of exercise addiction: Examining gender differences. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2018, 18, 1738–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. On the functional properties of self-efficacy revisited. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 9–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, M.R.; Crawford, K.L.; Jackson, B. Social cognitive theory and physical activity: Mechanisms of behavior change, critique, and legacy. Psychol. Sports Exerc. 2019, 42, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bircher, J.; Griffiths, M.D.; Kasos, K.; Demetrovics, Z.; Szabo, A. Exercise addiction and personality: A two-decade systematic review of the empirical literature (1995–2015). Balt. J. Sports Health Sci. 2017, 3, 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain, S.R.; Grant, J.E. Is problematic exercise really problematic? A dimensional approach. CNS Spectr. 2020, 25, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.; Rhodes, P.; Touyz, S.; Hay, P. The relationship between obsessive-compulsive personality disorder traits, obsessive-compulsive disorder and excessive exercise in patients with anorexia nervosa: A systematic review. J. Eat. Disord. 2013, 1, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fineberg, N.A.; Day, G.A.; de Koenigswarter, N.; Reghunandanan, S.; Kolli, S.; Jefferies-Sewell, K.; Hranov, G.; Laws, K.R. The neuropsychology of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder: A new analysis. CNS Spectr. 2015, 20, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redden, S.A.; Mueller, N.E.; Cougle, J.R. The impact of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder in perfectionism. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2023, 27, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeber, J. Multidimensional perfectionism and the DSM-5 personality traits. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2014, 64, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, H.K.; Kerr, A.W.; Kozub, S.A.; Finnie, S.B. Motivational antecedents of obligatory exercise: The influence of achievement goals and multidimensional perfectionism. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2007, 8, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrandrea, P.; Gonidakis, F. Exercise addiction and orthorexia nervosa in Crossfit: Exploring the role of perfectionism. Current Psychology 2022, 42, 25151–25159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, I.; de Luca, I.; Giorgetti, V.; Cicconcelli, D.; Bersani, F.S.; Imperatori, C.; Abdi, S.; Negri, A.; Esposito, G.; Corazza, O. Fitspiration on social media: Body-image and other psychopathological risks among young adults. A narrative review. Emerg. Trends Drugs Addict. Health 2021, 1, 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, C.; Tod, D.; Molnar, G. A systematic review of the drive for muscularity research area. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2014, 7, 18–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egli, T.; Bland, H.W.; Melton, B.F.; Czech, D.R. Influence of age, sex, and race on college students’ exercise motivation of physical activity. J. Am. Coll. Health 2011, 59, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard, M.; Cramblitt, B. Media influence on drive for thinness and drive for muscularity. Sex Roles 2014, 71, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.; Reeves, M.; Ryrie, A. The influence of physical activity, sport and exercise motives among UK-based university students. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2015, 39, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicent, M.; Sanmartín, R.; Gonzálvez, C.; Vásconez-Rubio, O.; García-Fernández, J.M. Perfectionism, Motives, and Barriers to Exercise from a Person-Oriented Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rounsefell, K.; Gibson, S.; McLean, S.; Blair, M.; Molenaar, A.; Brennan, L.; Truby, H.; McCaffrey, T.A. Social media, body image and food choices in healthy young adults: A mixed methods systematic review. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 77, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, L.; Owens, G.; Cruz, B.D.P. Identifying the features of an exercise addiction: A Delphi study. J. Behav. Addict. 2016, 5, 474–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansell, E.B.; Pinto, A.; Crosby, R.D.; Becker, D.F.; Añez, L.M.; Paris, M.; Grilo, C.M. The prevalence and structure of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder in Hispanic psychiatric outpatients. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2010, 41, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diedrich, A.; Voderholzer, U. Obsessive–compulsive personality disorder: A current review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2015, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy-Izquierdo, D.; Navarrón, E.; López-Mora, C.; González-Hernández, J. Exercise Addiction in the Sports Context: What Is Known and What Is Yet to Be Known. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2023, 21, 1057–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, O.; Reilly, J.; Kremer, J. Excessive exercise: From quantitative categorisation to a qualitative continuum approach. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2011, 19, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boat, R.; Cooper, S.B. Self-Control and Exercise: A Review of the Bi-Directional Relationship. Brain Plast. 2019, 5, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ. Behav. 2004, 31, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwan, D.; Harden, S.M.; Zumbo, B.D.; Syvester, B.D.; Kaulius, M.; Ruissen, G.R.; Beauchamp, M.R. The effectiveness of multi-component goal setting intervention for changing physical activity behavior: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2016, 10, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, W.W.; Kupzyk, K.; Norman, J.; Bills, S.E.; Bosak, K.; Dunn, S.L.; Deka, P.; Pozehl, B. Negative attitudes, self-efficacy, and relapse management mediate long-term adherence to exercise in patients with heart failure. Ann. Behav. Med. Publ. Soc. Behav. Med. 2021, 55, 1031–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuley, E.; Mullen, S.P.; Szabo, A.N.; White, S.M.; Wójcicki, T.R.; Mailey, E.L.; Gothe, N.P.; Olson, E.A.; Voss, M.; Erickson, K.; et al. Self-regulatory processes and exercise adherence in older adults: Executive function and self-efficacy effects. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 41, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Gao, S.; Chen, B.; Liu, C.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, Y. A study on the correlation between undergraduate students’ exercise motivation, exercise self-efficacy, and exercise behaviour under the COVID-19 epidemic environment. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 946896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levallius, J.; Collin, C.; Birgegård, A. Now you see it, Now you don’t: Compulsive exercise in adolescents with an eating disorder. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafran, R.; Mansell, W. Perfectionism and psychopathology: A review of research and treatment. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 21, 879–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, S.C.; Kling, J.; Wängqvist, M.; Frisén, A.; Syed, M. Identity and the body: Trajectories of body esteem from adolescence to emerging adulthood. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 54, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranta, M.; Dietrich, J.; Salmela-Aro, K. Career and romantic relationship goals and concerns during emerging adulthood. Emerg. Adulthood 2014, 2, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucchianeri, M.M.; Arikian, A.J.; Hannan, P.J.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Body dissatisfaction from adolescence to young adulthood: Findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. Body Image 2013, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett-Gunter, R.; McEwan, D.; Kamarhie, A. Physical activity and body image among men and boys: A meta-analysis. Body Image 2017, 22, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.; Halliwell, E. Examination of a sociocultural model of excessive exercise among male and female adolescents. Body Image 2010, 7, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R.; Jerusalem, M. Generalized self-efficacy scale. In Measures in Health psychology: A User’s Portfolio. Causal and Control Beliefs; Weinman, J., Wright, S., Johnston, M., Eds.; NFER–Nelson: Windsor, UK, 1995; pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, U.; Doña, B.G.; Sud, S.; Schwarzer, R. Is general self-efficacy a universal construct? Psychometric findings from 25 countries. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2002, 18, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romppel, M.; Herrmann-Lingen, C.; Wachter, R.; Edelmann, F.; Düngen, H.D.; Pieske, B.; Grande, G. A short form of the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE-6): Development, psychometric properties and validity in an intercultural non-clinical sample and a sample of patients at risk for heart failure. GMS Psycho-Soc.-Med. 2013, 10, Doc01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyler, S.E. Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-4 (PDQ-4); New York State Psychiatric Institute: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, N.; Gutiérrez, F.; Casas, M. Diagnostic agreement between the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-4+ (PDQ-4+) and its Clinical Significance Scale. Psicothema 2013, 25, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdin, E.; Koh, K.G.; Subramaniam, M.; Guo, M.E.; Leo, T.; Teo, C.; Tan, E.E.; Chong, S.A. Validity of the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire—4 (PDQ-4+) among mentally ill prison inmates in Singapore. J. Personal. Disord. 2011, 25, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopwood, C.J.; Thomas, K.M.; Markon, K.E.; Wright, A.G.; Krueger, R.F. DSM-5 personality traits and DSM–IV personality disorders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2012, 121, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouvard, M.; Vuachet, M.; Marchand, C. Examination of the screening properties of the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-4+ (PDQ-4+) in a non-clinical sample. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2011, 8, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. PROCESS: A Versatile Computational Tool for Observed Variable Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Modeling [White paper]. 2012. Available online: http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- Esnaola, I.; Rodríguez, A.; Goñi, A. Body dissatisfaction and perceived sociocultural pressures: Gender and age differences. Salud Ment. 2010, 33, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Bégin, C.; Turcotte, O.; Rodrigue, C. Psychosocial factors underlying symptoms of muscle dysmorphia in a non-clinical sample of men. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 272, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, M.P.; Ricciardelli, L.A. Body image and strategies to lose weight and increase muscle among boys and girls. Health Psychol. 2003, 22, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, H.; Mountford, V.; Brown, G. Beliefs about excessive exercise in eating disorders: The role of obsessions and compulsions. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2011, 19, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalk, H.M.; Miller, S.E.; Roach, M.E.; Schultheis, K.S. Predictors of obligatory exercise among undergraduates: Differential implications for counseling college men and women. J. Coll. Couns. 2013, 16, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, P.; Ciclitira, K.E. Men and dieting: A qualitative analysis. J. Health Psychol. 2005, 10, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyde, J.; Hankins, M.; Deale, A.; Marteau, T.M. Interventions to increase self-efficacy in the context of addiction behaviours: A systematic literature review. J. Health Psychol. 2008, 13, 607–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Internal Consistency | Total M (SD) | Male M (SD) | Female M (SD) | Sex Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | - | 21.68 (2.00) | 21.58 (2.05) | 21.78 (1.95) | t (1226) = −1.74 *, Cohen’s d = 0.10 |

| EA | 0.82 | 17.30 (6.41) | 18.55 (6.12) | 16.07 (6.45) | t (1225.11) = 6.92 ***, Cohen’s d = 0.39 |

| OCPD | 0.66 | 2.86 (2.06) | 2.83 (2.09) | 2.90 (2.04) | t (1226) = −0.584, Cohen’s d = 0.03 |

| SE | 0.88 | 30.86 (4.72) | 31.34 (4.72) | 30.40 (4.67) | t (1226) = 3.52 **, Cohen’s d = 0.20 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | - | ||||

| Sex | 0.05 | - | |||

| EA | 0.05 | −0.19 *** | - | ||

| OCPD | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.11 *** | - | |

| SE | 0.03 | −0.10 *** | 0.16 *** | −0.17 *** | - |

| At Risk n (% Subgroup) | Symptomatic n (% Subgroup) | Asymptomatic n (% Subgroup) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 1228) | 35 (2.9%) | 730 (59.4%) | 463 (37.7%) |

| Male (n = 606) | 24 (4.0%) | 409 (67.5%) | 173 (28.5%) |

| Female (n = 622) | 11 (1.8%) | 321 (51.6%) | 290 (46.6%) |

| Sex Differences | χ2 = 4.83 ** | χ2 = 10.61 * | χ2 = 29.57 |

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | p | F | df | R2 | R2 Change | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | |||||||||

| 1 | 25.99 | 2, 1225 | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.000 *** | ||||||

| Age | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 2.01 | 0.045 * | ||||||

| Sex | −2.52 | 0.36 | −0.20 | −0.20 | 0.000 *** | ||||||

| 2 | 26.71 | 4, 1223 | 0.080 | 0.040 | 0.000 *** | ||||||

| Age | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 1.80 | 0.072 | ||||||

| Sex | −2.33 | 0.35 | −0.18 | −6.59 | 0.000 *** | ||||||

| OCPD | 0.44 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 5.11 | 0.000 *** | ||||||

| SE | 0.23 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 5.96 | 0.000 *** | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tang, C.S.K.; Gan, K.Q.; Lui, W.K. The Associations between Obsessive Compulsive Personality Traits, Self-Efficacy, and Exercise Addiction. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 857. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13100857

Tang CSK, Gan KQ, Lui WK. The Associations between Obsessive Compulsive Personality Traits, Self-Efficacy, and Exercise Addiction. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(10):857. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13100857

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Catherine So Kum, Kai Qi Gan, and Wai Kin Lui. 2023. "The Associations between Obsessive Compulsive Personality Traits, Self-Efficacy, and Exercise Addiction" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 10: 857. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13100857

APA StyleTang, C. S. K., Gan, K. Q., & Lui, W. K. (2023). The Associations between Obsessive Compulsive Personality Traits, Self-Efficacy, and Exercise Addiction. Behavioral Sciences, 13(10), 857. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13100857