Impact of Met-Expectation of Athletic Justice on Athletic Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment via Leader–Member Exchange among Elite Saudi Arabian Athletes

Abstract

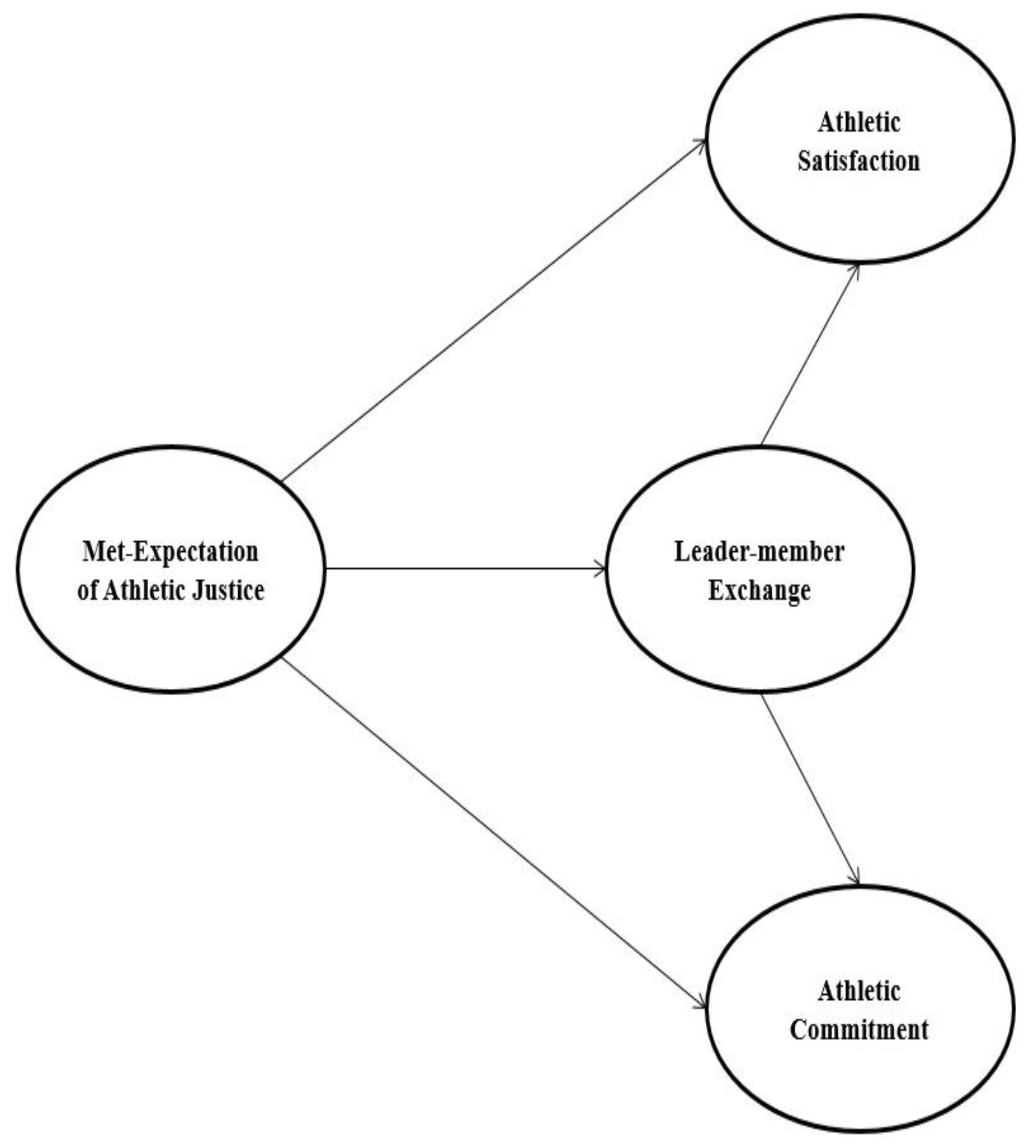

:1. Introduction

Met-Expectation

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. Organizational Justice in Sport

2.2. Outcomes of Organizational Justice

2.2.1. Attitudinal Outcomes: Athlete Satisfaction and Team Commitment

2.2.2. Leader–Member Exchange as a Mediator

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Survey Procedure

3.2. Instrumentation

3.2.1. Met-Expectation

3.2.2. Outcome Variables

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Validity and Reliability

4.2. Results of SEM

5. Discussion

6. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bandura, C.T.; Kavussanu, M. Authentic leadership in sport: Its relationship with athletes’ enjoyment and commitment and the mediating role of autonomy and trust. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2018, 6, 968–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowett, S. Coaching effectiveness: The coach–athlete relationship at its heart. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 16, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Jeong, Y.; Kim, S. The relationship between coaching behavior and athlete burnout: Mediating effects of communication and the coach–athlete relationship. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 22, 8618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosai, J.; Jowett, S.; Nascimento-Júnior, J.R.A.D., Jr. When leadership, relationships and psychological safety promote flourishing in sport and life. Sports Coach. Rev. 2021, 2, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malloy, E.; Kavussanu, M.; Mackman, T. The effects of authentic leadership on athlete outcomes: An experimental study. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2023, 1, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Backer, M.; Boen, F.; Ceux, T.; De Cuyper, B.; Høigaard, R.; Callens, F.; Fransen, K.; Vande Broek, G. Do perceived justice and need support of the coach predict team identification and cohesion? Testing their relative importance among top volleyball and handball players in Belgium and Norway. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2011, 12, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Backer, M.; Boen, F.; Van Puyenbroeck, S.; Reynders, B.; Van Meervelt, K.; Vande Broek, G. Should team coaches care about justice? Perceived justice mediates the relation between coaches’ autonomy support and athletes. Satisfaction and self-rated progression. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2020, 16, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Backer, M.; Van Puyenbroeck, S.; Fransen, K.; Reynders, B.; Boen, F.; Malisse, F.; Vande Broek, G. Does fair coach behavior predict the quality of athlete leadership among Belgian volleyball and basketball players: The vital role of team identification and task cohesion. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 645764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, D.; Reynoso-Sánchez, L.; García-Herrero, J.; Gómez-López, M.; Carcedo, R. Coach competence, justice, and authentic leadership: An athlete satisfaction model. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2022, 18, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J. A taxonomy of organizational justice theories. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikbin, D.; Hyun, S.S.; Iranmanesh, M.; Foroughi, B. Effects of perceived justice for coaches on athletes’ trust, commitment, and perceived performance: A study of futsal and volleyball players. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2014, 4, 561–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.L. Trust and breach of the psychological contract. Adm. Sci. Q. 1996, 41, 574–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, L.; Steers, R. Organizational, work, and personal factors in employee turnover and absenteeism. Psychol. Bull. 1973, 80, 151–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNulty, Y. Modern expatriation through the lens of global careers, psychological contracts, and individual return on investment. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2014, 33, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Oh, T.; Lee, S.; Andrew, D.P.S. Relationships between met-expectation and attitudinal outcomes of coaches in intercollegiate athletics. Sport Manag. Rev. 2019, 22, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.; Andrew, D.P.S. The impact of mentoring opportunities and reward structure on role behavior expectations in mentoring relationships among sport management faculty. In Proceedings of the 23rd Annual North American Society for Sport Management Conference, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 29 May–3 June 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Trail, G.T.; Lim, J.; Kim, Y.K. The role of psychological contract in intention to continue volunteering. J. Sport Manag. 2009, 23, 549–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, T.; Darcy, S.; Hoye, R.; Cuskelly, G. Using psychological contract theory to explore issues in effective volunteer management. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2006, 6, 123–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Molinsky, A.; Margolis, J.D.; Kamin, M.; Schiano, W.T. The performer’s reactions to procedural injustice: When prosocial identity reduces prosocial behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 39, 319–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Scott, B.A.; Rodell, J.B.; Long, D.M.; Zapata, C.P.; Conlon, D.E.; Wesson, M.J. Justice at the millennium, a decade later: A meta-analytic test of social exchange and affect-based perspectives. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 199–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hums, M.A.; Chelladurai, P. Distributive justice in intercollegiate athletics: Development of an instrument. J. Sport Manag. 1994, 8, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmore, S.W.; Mahony, D.F.; Andrew, D.P.S.; Hums, M.A. Examining fairness perceptions of financial resource allocation in U.S. Olympic sport. J. Sport Manag. 2009, 23, 429–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, J.; Turner, B.; Fink, J.; Pastore, D. Organizational justice as a predictor of job satisfaction: An examination of head basketball coaches. J. Study Sports Athl. Educ. 2007, 1, 321–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, J.S.; Turner, B.A.; Pack, S.M. The influence of organizational justice on perceived organizational support in a university recreational sports setting. Int. J. Sport Manag. Mark. 2009, 6, 106–123. [Google Scholar]

- Kerwin, S.; Jeremy, S.; Jordan, J.; Turner, B. Organizational justice and conflict: Do perceptions of fairness influence disagreement? Sport Manag. Rev. 2015, 18, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Perceived organizational support as a mediator between distributive justice and sport referees’ job satisfaction and career commitment. Ann. Leis. Res. 2017, 20, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Greenberg, J.M. Organizational justice: A fair assessment of the state of the literature. In Organizational Behavior: The State of Science, 2nd ed.; Greenberg, J., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 165–210. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, J. The social side of fairness: Interpersonal and information classes of organizational justice. In Justice in the Workplace: Approaching Fairness in Human Resource Management; Cropanzano, R., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1993; pp. 79–103. [Google Scholar]

- Colquitt, J.A. On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.S. Inequity in social exchange. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1965, 2, 267–299. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal, G.S. What should be done with equity theory. In Social Exchange: Advances in Theory and Research; Gergen, K.J., Greenberg, M.S., Willis, R.H., Eds.; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bies, R.J.; Moag, J.S. Interactional justice: Communication criteria of fairness. Res. Negot. Organ. 1986, 1, 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Ambrose, M.L. Procedural and distributive justice are more similar than you think: A monistic perspective and a research agenda. In Advances in Organization Justice; Greenberg, J., Cropanzano, R., Eds.; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2001; pp. 119–151. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Jeong, Y. Developing the healthy and competitive organization in the sports environment: Focused on the relationships between organizational justice, empowerment and job performance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 17, 9142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelladurai, P.; Kerwin, S. Human Resource Management in Sport and Recreation, 3rd ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Hong, S.; Magnusen, M.; Rhee, Y. Hard knock coaching: A cross-cultural study of the effects of abusive leader behaviors on athlete satisfaction and commitment through interactional justice. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2020, 5–6, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Magnusen, M.J.; Andrew, D.P. Sport team culture: Investigating how vertical and horizontal communication influence citizenship behaviors via organizational commitment. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 2017, 48, 398–418. [Google Scholar]

- Graen, G.B.; Scandura, T.A. Toward a psychology of dyadic organizing. Res. Organ. Behav. 1987, 9, 175–208. [Google Scholar]

- Cranmer, G.A.; Myers, S.A. Sports teams as organizations: A leader–member exchange perspective of player communication with coaches and teammates. Commun. Sport 2015, 3, 100–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandura, T.A.; Graen, G.B.; Novak, M.A. When managers decide not to decide autocratically: An investigation of leader-member exchange and decision influence. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Charahsh, Y.; Spector, P.E. The role of justice in organizations: A meta-analysis. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2001, 86, 278–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekleab, A.G.; Takeuchi, R.; Taylor, M.S. Extending the chain of relationships among organizational justice, social exchange, and employee reaction: The role of contract violations. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.C. Effects of leadership and leader-member exchange on commitment. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2005, 26, 655–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Westland, J.C. Lower bounds on sample size in structural equation modeling. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2010, 9, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Love, A.; Oh, T.; Alahmad, M. Athletic Justice: Scale Development and Validation. In Proceedings of the 2023 Asian Association for Sport Management Conference, Kuching, Malaysia, 19–20 August 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Scandura, T.A.; Graen, G.B. Moderating effects of initial leader-member exchange status on the effects of a leadership intervention. J. Appl. Psychol.. 1984, 69, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Locke, E.A.; Durham, C.C.; Kluger, A.N. Dispositional effects on job and life satisfaction: The role of core evaluations. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J.; Smith, C.A. Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 538–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jowett, S.; Shanmugam, V.; Caccoulis, S. Collective efficacy as a mediator of the association between interpersonal relationships and athlete satisfaction in team sports. Int. J. Sport Exer. Psychol. 2012, 1, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Cruz, A. The influence of coaches’ leadership styles on athletes’ satisfaction and team Cohesion: A meta-analytic approach. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2016, 11, 900–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Dhar, R.L. Effects of stress, LMX, and perceived organizational support on service quality: Mediating effects of organizational commitment. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2014, 21, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prapavessis, H.; Carron, A.V. Sacrifice, cohesion, and conformity to norms in sport teams. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 1997, 1, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggieri, S.; Abbate, C.S. Leadership style, self-sacrifice, and team identification. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2013, 41, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | Percent (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 238 | 82.3 |

| Female | 51 | 17.6 | |

| Sports | Football | 61 | 21.1 |

| Athletics | 38 | 13.1 | |

| Tennis | 25 | 8.7 | |

| Basketball | 18 | 6.2 | |

| Volleyball | 15 | 5.2 | |

| Cycling | 14 | 4.8 | |

| Taekwondo | 14 | 4.8 | |

| Wrestling | 13 | 4.5 | |

| Gymnastics | 10 | 3.5 | |

| Fencing | 8 | 2.8 | |

| Jujitsu | 8 | 2.8 | |

| Weightlifting | 8 | 2.8 | |

| Rowing | 7 | 2.4 | |

| Others | 50 | 17.3 |

| Construct | Item | Mean | S.D. | Loadings | CR | AVE | A |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Met-Expectation | 0.924 | 0.578 | 0.923 | ||||

| My coach addresses influence from administrators in a way I expect. | 4.88 | 1.89 | 0.747 | ||||

| My coach handles influence from political factors in a way I expect. | 4.97 | 1.85 | 0.643 | ||||

| My coach addresses influence from team members’ parents in a way I expect. | 5.16 | 1.66 | 0.739 | ||||

| My coach provides team members with feedback about decisions and their implementation in a way I expect. | 4.93 | 1.98 | 0.688 | ||||

| My coach communicates their decisions in a way I expect. | 4.76 | 1.97 | 0.785 | ||||

| My coach communicates with everyone on the team in a way I expect. | 4.85 | 2.08 | 0.782 | ||||

| My coach meets my expectations by treating everyone on the team with respect. | 5.72 | 1.69 | 0.795 | ||||

| My coach meets my expectations by treating everyone on the team in a polite manner. | 5.57 | 1.77 | 0.829 | ||||

| My coach meets expectations by treating everyone on the team with dignity. | 5.63 | 1.74 | 0.832 | ||||

| Athlete Satisfaction | 0.888 | 0.728 | 0.880 | ||||

| Most days I am enthusiastic about my team and my sport. | 6.08 | 1.44 | 0.759 | ||||

| I feel satisfied with my team. | 5.56 | 1.67 | 0.912 | ||||

| I find real enjoyment in my team. | 5.82 | 1.51 | 0.861 | ||||

| Team Commitment | 0.865 | 0.683 | 0.865 | ||||

| I do not feel a strong sense of “belonging” to my team. | 4.89 | 2.07 | 0.775 | ||||

| I do not feel “emotionally attached” to my team. | 5.15 | 2.03 | 0.864 | ||||

| I do not feel like “part of the family” in my team. | 5.18 | 2.11 | 0.839 | ||||

| LMX | 0.890 | 0.688 | 0.915 | ||||

| I always know how satisfied my coach is with what I do. | 5.23 | 1.87 | 0.728 | ||||

| My coach completely understands my problems and needs. | 5.03 | 2.02 | 0.808 | ||||

| My coach fully recognizes my potential. | 5.28 | 1.84 | 0.661 | ||||

| My coach certainly would be personally inclined to help solve problems | 5.22 | 1.86 | 0.819 | ||||

| I certainly can count on my coach to “bail me out” at his/her expense when I really need it. | 4.44 | 2.01 | 0.728 | ||||

| I have enough confidence in my coach that I certainly would defend and justify his/her decisions if he/she were not present to do so. | 4.90 | 2.07 | 0.888 | ||||

| I would characterize my relationship with my coach as extremely effective. | 5.22 | 1.84 | 0.814 | ||||

| x2 = 4594.612, df = 231 p < 0.001, CFI = 0.919, TLI = 0.908, RMSEA = 0.078, SRMR = 0.053 | |||||||

| Variables | √AVE | ME | AS | AC | LMX |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ME | 0.760 | 1 | |||

| AS | 0.853 | 0.459 | 1 | ||

| TC | 0.826 | 0.182 | 0.389 | 1 | |

| LMX | 0.829 | 0.814 | 0.471 | 0.206 | 1 |

| To | From | Std. B | Std.err | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMX | ME | 0.814 * | 0.071 | <0.001 |

| AS | ME | 0.225 * | 0.087 | 0.046 |

| LMX | 0.288 * | 0.091 | 0.011 | |

| TC | ME | 0.043 | 0.142 | 0.733 |

| LMX | 0.171 | 0.148 | 0.174 | |

| x2 = 4594.621, df = 231 p < 0.001, CFI = 0.919, TLI = 0.908, RMSEA = 0.078, SRMR = 0.053 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, S.; Oh, T.; Love, A.; Alahmad, M.E. Impact of Met-Expectation of Athletic Justice on Athletic Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment via Leader–Member Exchange among Elite Saudi Arabian Athletes. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 836. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13100836

Kim S, Oh T, Love A, Alahmad ME. Impact of Met-Expectation of Athletic Justice on Athletic Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment via Leader–Member Exchange among Elite Saudi Arabian Athletes. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(10):836. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13100836

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Seungmo, Taeyeon Oh, Adam Love, and Majed Essa Alahmad. 2023. "Impact of Met-Expectation of Athletic Justice on Athletic Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment via Leader–Member Exchange among Elite Saudi Arabian Athletes" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 10: 836. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13100836

APA StyleKim, S., Oh, T., Love, A., & Alahmad, M. E. (2023). Impact of Met-Expectation of Athletic Justice on Athletic Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment via Leader–Member Exchange among Elite Saudi Arabian Athletes. Behavioral Sciences, 13(10), 836. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13100836