Information Literacy as a Predictor of Work Performance: The Mediating Role of Lifelong Learning and Creativity

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How does information literacy influence work performance?

- How does information literacy influence lifelong learning and creativity?

- How do lifelong learning and creativity influence work performance?

- How do lifelong learning and creativity mediate the relationship between information literacy and work performance?

1.1. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

1.1.1. Workplace Information Literacy (WIL)

1.1.2. IL and Work Performance

1.1.3. IL and Lifelong Learning

1.1.4. IL and Creativity

1.1.5. Lifelong Learning and Work Performance

1.1.6. Creativity and Work Performance

1.1.7. IL and Work Performance: Mediating Role of Lifelong Learning and Creativity

2. Methodology

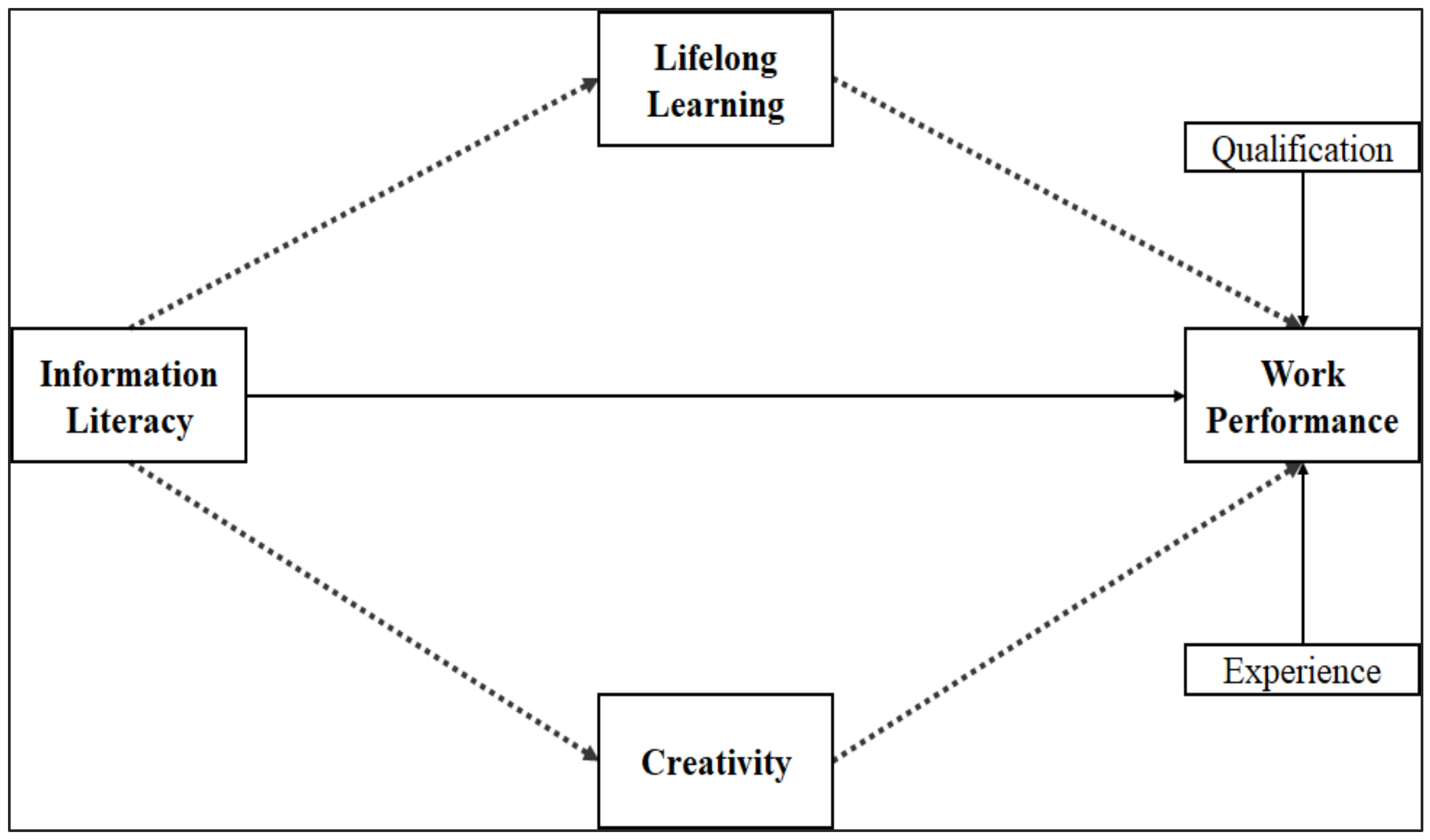

2.1. Research Model

2.2. Design and Method

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Information Literacy

2.3.2. Lifelong Learning

2.3.3. Creativity

2.3.4. Work Performance

2.4. Population and Sampling

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

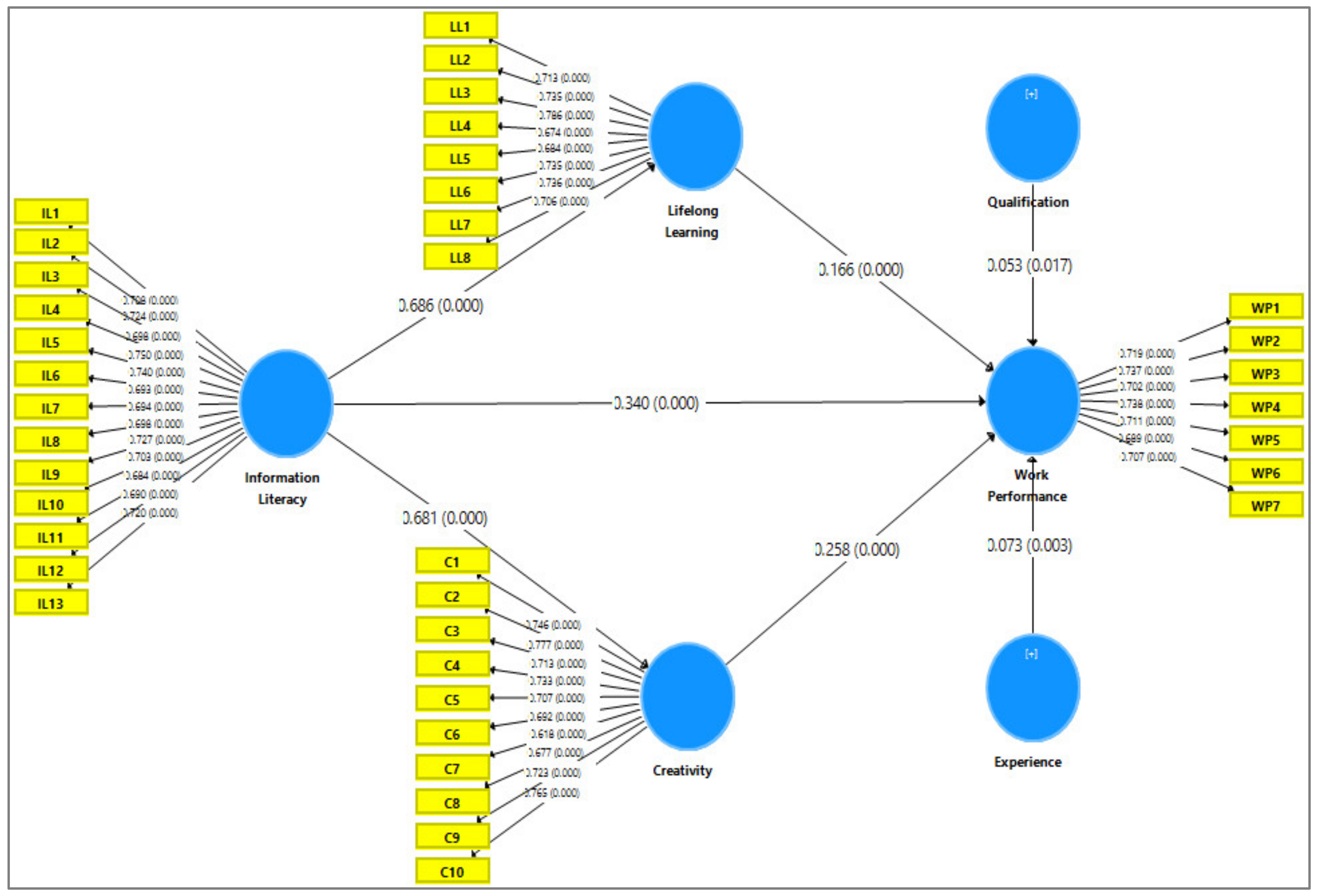

3.2. The Measurement Model

3.3. Descriptive Analysis

3.4. Structural Model

3.5. Mediating Effect

4. Discussion

4.1. Conclusions and Implications

4.2. Limitation and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Forster, M. Information Literacy in the Workplace; Facet Publishing: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, F.; Widén, G.; Huvila, I. The impact of workplace information literacy on organizational innovation: An empirical study. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 51, 102041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, M.A.; Rafique, F. Information literacy in the workplace: A case of scientists from Pakistan. Libri 2018, 68, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasikala, C.; Kumari, C.L. Information Literacy at the Workplace: A Case Study of Steel Industry. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Information Literacy (ECIL), Istanbul, Turkey, 22–25 October 2013; p. 199. [Google Scholar]

- Ottonicar, S.L.C.; Valentim, M.L.P.; Feres, G.G. Managers’ information literacy: A case study of a cluster in Brazil. AtoZ: Novas Práticas Em Inf. E Conhecimento 2020, 7, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, M.A. Information literacy self-efficacy of scientists working at the Pakistan Council of Scientific and Industrial Research. Ir. Inf. Res. 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Majid, S.; Foo, S. The Role of Information Literacy in Environmental Scanning as a Strategic Information System-A Study of Singapore SMEs. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Information Management in a Changing World, An-kara, Turkey, 22–24 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, C.S. Workplace experiences of information literacy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 1999, 19, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inayatillah, F. Media and Information Literacy (MIL) in journalistic learning: Strategies for accurately engaging with information and reporting news. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 296, 012007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suorsa, A.; Bossaller, J.S.; Budd, J.M. Information Literacy, Work, and Knowledge Creation: A Hermeneutic Phenomenological Point of View. Libr. Q. 2021, 91, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, M.A.; Shah, N.A. Information literacy in the legal workplace: Current state of lawyers’ skills in Pakistan. J. Librariansh. Inf. Sci. 2022, 09610006221081895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-S. Information literacy, creativity and work performance. Inf. Dev. 2018, 35, 676–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.; Rigtering, J.C.; Covin, J.G.; Bouncken, R.B.; Kraus, S. Innovative behaviour, trust and perceived workplace performance. Br. J. Manag. 2018, 29, 750–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, B.L.; Lepine, J.A.; Crawford, E.R. Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. What having a “growth mindset” actually means. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2016, 13, 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Coşkun, Y.D.; Demirel, M. Lifelong learning tendency scale: The study of validity and reliability. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 5, 2343–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, W. Robotham Establishing a Culture of Lifelong Learning in the Workplace. Available online: https://extension.psu.edu/establishing-a-culture-of-lifelong-learning-in-the-workplace (accessed on 19 May 2022).

- Leone, S.A. Core Processes of Creativity in Teams: Developing a Behavioral Coding Scheme University of Nebraska at Omaha. 2020. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2427334035?pq (accessed on 19 May 2022).

- Kark, R.; Van Dijk, D.; Vashdi, D.R. Motivated or demotivated to be creative: The role of self-regulatory focus in transformational and transactional leadership processes. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 67, 186–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arp, L.; Woodard, B.S. Curiosity and creativity as attributes of information literacy. Ref. User Serv. Q. 2004, 44, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood, A. Learn. Work. Repeat. 2021. Available online: https://www.candlefox.com/blog/lifelong-learning/ (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Feng, L.; Jih-Lian, H. Effects of teachers’ information literacy on lifelong learning and school effectiveness. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2016, 12, 1653–1663. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.-P.; Hsu, P.-C. The correlation between employee information literacy and employee creativity. Qual. Quant. 2015, 49, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, L.; Hall, H. Workplace information literacy: A bridge to the development of innovative work behaviour. J. Doc. 2021, 77, 1343–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.A.; Asghar, M. Information seeking behavior of Pakistani newspaper journalists. Pak. J. Inf. Manag. Libr. 2016, 10, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frau-Meigs, D. How Disinformation Reshaped the Relationship between Journalism and Media and Information Literacy (MIL): Old and New Perspectives Revisited. Digit. J. 2022, 10, 912–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, H. Information skills and literacy in investigative journalism in the social media era. J. Inf. Sci. 2022, 01655515221094442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, U.; Batool, S.H.; Malik, A.; Mahmood, K.; Safdar, M. Bonding between information literacy and personal information management practices: A survey of electronic media journalists. Inf. Learn. Sci. 2022, 123, 298–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, C. Information literacy as a catalyst for educational change: A background paper. In Proceedings of the International Information Literacy Conferences and Meetings, NCLIS.gov, Prague, Czech Republic, 20–23 September 2003; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gasteen, G.; O’Sullivan, C. Working towards an information literate law firm. In Information Literacy Around the World: Advances in Programs and Research; Charles Sturt University: Bathurst, Austria, 2000; pp. 109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, J. Information and work: Extending the roles of information professionals. In Proceedings of the Challenging Ideas—Proceedings of the ALIA 2004 Biennial Conference, Queensland, Australia, 21–24 September 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, A. Learning to put out the red stuff: Becoming information literate through discursive practice. Libr. Q. 2007, 77, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheuk, B. Delivering Business Value through Information Literacy in the Workplace. Libri 2008, 58, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solmaz, D.Y. Relationship between Lifelong Learning Levels and Information Literacy Skills in Teacher Candidates. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 5, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleverley, P.H.; Burnett, S.; Muir, L. Exploratory information searching in the enterprise: A study of user satisfaction and task performance. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2017, 68, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malafi, E.; Liu, G.; Goldstein, S.; Grassian, E.; LeMire, S. Business and workplace information literacy: Three perspectives. Ref. User Serv. Q. 2017, 57, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, S. Information literacy skills in the workplace: Examining early career advertising professionals. J. Bus. Financ. Librariansh. 2017, 22, 111–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheuk, B. Information Literacy in the Workplace Context: Issues, Best Practices and Challenges; White Paper Prepared for UNESCO, the US National Commission on Libraries and Information Science, and the National Forum on Information Literacy, for Use at the Information Literacy Meeting of Experts; Prague, Czech Republic; Retrieved March, 2002; p. 2004. Available online: http://www.nclis.gov/libinter/infolitconf&meet/papers/cheuk-fullpaper.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Gardner, D.P.; Studies, C.f.L. Learning at Work. Tennessee Profiles in Workplace Adult Basic Education. University of Tennessee, 2000. Available online: http:http/www.cls.utk.edu/pdf/learningatwork.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Goad, T.W. Information Literacy and Workplace Performance; Greenwood Publishing Group: Westport, CT, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Travis, T.A. From the classroom to the boardroom: The impact of information literacy instruction on workplace research skills. Educ. Libr. 2011, 34, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jinadu, I.; Kaur, K. Information literacy at the workplace: A suggested model for a developing country. Libri 2014, 64, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadia, H.; Naveed, M.A. Workplace Information Literacy: Current State of Research Published from South-Asia. Library Philos. Pract. 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.-K.; Hung, C.-H. An examination of the mediating role of person-job fit in relations between information literacy and work outcomes. J. Work. Learn. 2010, 22, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popoola, S.O.; Tabuke, W.P. Psychological Capital and Information Literacy Skills as Determinants of Job Performance of Academic Library Employees in State Universities in South West, Nigeria; Regional Institute of Information and Knowledge Management: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Majid, S.; Foo, S. Environmental scanning: An application of information literacy skills at the workplace. J. Inf. Sci. 2010, 36, 719–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isfandyari-Moghaddam, A.; Kashi-Nahanji, V. Does information technology affect the level of information literacy? A comparative case study of high school students. Aslib Proc. 2011, 63, 618–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, A. Information literacy for lifelong learning. In Proceedings of the World Library and Information Congress, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 22–27 August 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kozikoglu, I.; Onur, Z. Predictors of lifelong learning: Information literacy and academic self-efficacy. Cypriot J. Educ. Sci. 2019, 14, 492–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaussi, K.S.; Randel, A.E. Where to look? Creative self-efficacy, knowledge retrieval, and incremental and radical creativity. Creat. Res. J. 2014, 26, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, T.; Baviran, M. Investigating the Relationship between Information Literacy and Organizational Creativity: A Case Study. J. Knowl. Stud. 2022, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazizadeh, H.; Tabarzadi, M.; Khasseh, A.A. Relationship between Information Literacy Standards and Organizational Creativity among Employees of an Iranian Company (A Case of Tehran Electric Company). 2017. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1669/ (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Drewery, D.W.; Sproule, R.; Pretti, T.J. Lifelong learning mindset and career success: Evidence from the field of accounting and finance. High.Educ. Ski. Work. Based Learn. 2020, 10, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srimechai, N. Development of a Work Performance Enhancement Model for Lifelong Learning for Non-formal and Informal Education Volunteers. Sch. Hum. Sci. 2011, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Anggara, W.G.; Febriansyah, H.; Darmawan, R.; Cintyawati, C. Learning organization and work performance in Bandung city government in Indonesia: A path modeling statistical approach. Dev. Learn.Organ. Int. J. 2019, 33, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J. Creativity as a stepping stone toward a brighter future. J. Intell. 2018, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.Y. The Structural Relationship among Learning Goal Orientation, Creativity, Working Smart, Working Hard, and Work Performance of Salespersons. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2018, 18, 90–107. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.Y. The relationship between creativity and salespersons’ work performance: Depending on the classification of sales work and the industrial category. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2019, 19, 305–316. [Google Scholar]

- Ngo, L.V.; Nguyen, N.P.; Lee, J.; Andonopoulos, V. Mindfulness and job performance: Does creativity matter? Australas. Mark. J. (AMJ) 2020, 28, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterns, H.L.; Spokus, D.M. Lifelong learning and the world of work. In Older Workers in an Ageing Society; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; 288p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, F.W. İnformation literacy and lifelong learning. In Guidelines on Information Literacy for Lifelong Learning; IFLA: Hague, The Netherlands, 2006; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.K.; Surendran, B. Information literacy for lifelong learning. Int. J. Libr. Inf. Stud. 2015, 5, 130–137. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, H.N.; Iqbal, A.; Nasr, L. Employee engagement and job performance in Lebanon: The mediating role of creativity. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2019, 68, 506–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jnaneswar, K.A.; Ranjit, G. Explicating intrinsic motivation’s impact on job performance: Employee creativity as a mediator. J. Strat. Manag. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, T.L.; Emerson, M.R.; Moore, T.A.; Fial, A.; Hanna, K.M. Systematic review: Feasibility, reliability, and validity of maternal/caregiver attachment and bonding screening tools for clinical use. J. Pediatric Health Care 2019, 33, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.A.; Kim, Y. On the relationship between coefficient alpha and composite reliability. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, H.P.; Kline, T.J. Development the Employee Lifelong Learning Scale (ELLS). PAACE J. Lifelong Learn. 2007, 16, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Doyague, M.F.; González-Álvarez, N.; Nieto, M. An examination of individual factors and employees’ creativity: The case of Spain. Creat. Res. J. 2008, 20, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, L. Measuring individual work performance. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2014, 53, 856–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, J.; Qureshi, N.; Ashraf, M.A.; Rasool, S.F.; Asghar, M.Z. The effect of emotional intelligence and academic social networking sites on academic performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 14, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial least squares structural equation modeling. Handb. Mark. Res. 2017, 26, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Dijkstra, T.K.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Straub, D.W.; Ketchen Jr, D.J.; Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Calantone, R.J. Common beliefs and reality about PLS: Comments on Rönkkö and Evermann (2013). Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 17, 182–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Plan. 2013, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmborg, J. Critical information literacy: Implications for instructional practice. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2006, 32, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, T.B. Cognition, creativity, and entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2004, 19, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Purpur, G. Effects of Information Literacy Skills on Student Writing and Course Performance. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2016, 42, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igbinovia, M.O. Emotional self awareness and information literacy competence as correlates of task performance of academic library personnel. Libr. Philos. Pract. 2016, 1370, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Seifi, L.; Habibi, M.; Ayati, M. The effect of information literacy instruction on lifelong learning readiness. IFLA J. 2020, 46, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.G.; Morris, J.A.; Meredith, J.M.; Bishop, N. Chemistry infographics: Experimenting with creativity and information literacy. In Liberal Arts Strategies for the Chemistry Classroom; ACS Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 113–131. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, S.; Yang, H.H.; MacLeod, J.; Yu, L.; Wu, D. Investigating teenage students’ information literacy in China: A social cognitive theory perspective. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2019, 28, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, F.D.; Holmboe, E.S. Self-assessment in Lifelong Learning and Improving Performance in PracticePhysician Know Thyself. JAMA 2006, 296, 1137–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewery, D.; Nevison, C.; Pretti, T.J.; Pennaforte, A. Lifelong learning characteristics, adjustment and extra-role performance in cooperative education. J. Educ. Work. 2017, 30, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dul, J.; Ceylan, C. The Impact of a creativity-supporting work environment on a firm’s product innovation performance. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 1254–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Huang, X.; Wang, Y. Good marriage at home, creativity at work: Family–work enrichment effect on workplace creativity. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 749–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Categories | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | Up to 30 | 196 | 18.08 |

| 31–40 | 691 | 63.74 | |

| 41–50 | 182 | 16.78 | |

| 50+ | 15 | 1.38 | |

| Gender | Male | 701 | 64.66 |

| Female | 383 | 35.34 | |

| Qualification | Undergraduate | 113 | 10.42 |

| Graduate | 654 | 60.33 | |

| Postgraduate | 317 | 29.24 | |

| Experience (Years) | Up to 5 | 98 | 9.04 |

| 6–10 | 184 | 16.97 | |

| 11–15 | 728 | 67.15 | |

| 15+ | 74 | 8.94 | |

| Region | Lahore | 351 | 32.38 |

| Karachi | 347 | 32.01 | |

| Peshawar | 29 | 2.67 | |

| Quetta | 17 | 1.56 | |

| Islamabad | 340 | 31.36 |

| Scales | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | rho_A | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information Literacy (IL) | 0.918 | 0.918 | 0.93 | 0.504 | |

| IL1 | 0.708 | ||||

| IL2 | 0.724 | ||||

| IL3 | 0.698 | ||||

| IL4 | 0.750 | ||||

| IL5 | 0.740 | ||||

| IL6 | 0.693 | ||||

| IL7 | 0.694 | ||||

| IL8 | 0.698 | ||||

| IL9 | 0.727 | ||||

| IL10 | 0.703 | ||||

| IL11 | 0.684 | ||||

| IL12 | 0.690 | ||||

| IL13 | 0.720 | ||||

| Lifelong Learning (LL) | 0.868 | 0.87 | 0.897 | 0.521 | |

| LL1 | 0.713 | ||||

| LL2 | 0.735 | ||||

| LL3 | 0.786 | ||||

| LL4 | 0.674 | ||||

| LL5 | 0.684 | ||||

| LL6 | 0.735 | ||||

| LL7 | 0.736 | ||||

| LL8 | 0.706 | ||||

| Creativity | 0.894 | 0.898 | 0.913 | 0.513 | |

| C1 | 0.746 | ||||

| C2 | 0.777 | ||||

| C3 | 0.713 | ||||

| C4 | 0.733 | ||||

| C5 | 0.707 | ||||

| C6 | 0.692 | ||||

| C7 | 0.618 | ||||

| C8 | 0.677 | ||||

| C9 | 0.723 | ||||

| C10 | 0.765 | ||||

| Work Performance (WP) | 0.841 | 0.842 | 0.88 | 0.511 | |

| WP1 | 0.719 | ||||

| WP2 | 0.737 | ||||

| WP3 | 0.702 | ||||

| WP4 | 0.738 | ||||

| WP5 | 0.711 | ||||

| WP6 | 0.689 | ||||

| WP7 | 0.707 |

| Constructs | Creativity | Information Literacy | Lifelong Learning | Work Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creativity | 0.716 | |||

| Information Literacy | 0.681 | 0.71 | ||

| Lifelong Learning | 0.679 | 0.686 | 0.722 | |

| Work Performance | 0.607 | 0.639 | 0.578 | 0.715 |

| Dimensions | C-VIF | LL-VIF | WP-VIF | Model Fit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creativity (C) | 2.245 | SRMR | 0.0420 | ||

| Information Literacy (IL) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 2.278 | NFI | 0.870 |

| Lifelong Learning (LL) | 2.249 | RMS_Theta | 0.077 | ||

| Variables | R Square | R Square Adjusted |

|---|---|---|

| Lifelong Learning | 0.471 | 0.47 |

| Creativity | 0.463 | 0.463 |

| Work Performance | 0.482 | 0.480 |

| Variables | Creativity | Lifelong Learning | Work Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information Literacy | 0.863 | 0.889 | 0.098 |

| Lifelong Learning | 0.024 | ||

| Creativity | 0.057 |

| Variables | N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information Literacy | 1084 | 1 | 5 | 4.117 | 0.69315 |

| Lifelong Learning | 1084 | 1 | 5 | 4.393 | 0.71862 |

| Creativity | 1084 | 1 | 5 | 4.278 | 0.71199 |

| Work Performance | 1084 | 1 | 5 | 4.120 | 0.60987 |

| Hypotheses | Direct Relations | Coefficients | Mean | SD | t | p Values | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Information Literacy → Work Performance | 0.340 | 0.338 | 0.049 | 6.967 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2 | Information Literacy → Lifelong Learning | 0.686 | 0.687 | 0.026 | 26.426 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3 | Information Literacy → Creativity | 0.681 | 0.683 | 0.021 | 32.912 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H4 | Lifelong Learning → Work Performance | 0.166 | 0.166 | 0.044 | 3.785 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H5 | Creativity → Work Performance | 0.258 | 0.262 | 0.041 | 6.282 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Hypotheses | Indirect Relations | Coefficients | Mean | SD | t | p Values | Decision |

| H6 | Information Literacy → Lifelong Learning → Work Performance | 0.114 | 0.115 | 0.032 | 3.612 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H7 | Information Literacy → Creativity → Work Performance | 0.176 | 0.179 | 0.028 | 6.286 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Control Variables | Experience → Work Performance | 0.073 | 0.072 | 0.024 | 3.024 | 0.003 | Supported |

| Qualification → Work Performance | 0.053 | 0.054 | 0.022 | 2.383 | 0.017 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Naveed, M.A.; Iqbal, J.; Asghar, M.Z.; Shaukat, R.; Seitamaa-hakkarainen, P. Information Literacy as a Predictor of Work Performance: The Mediating Role of Lifelong Learning and Creativity. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13010024

Naveed MA, Iqbal J, Asghar MZ, Shaukat R, Seitamaa-hakkarainen P. Information Literacy as a Predictor of Work Performance: The Mediating Role of Lifelong Learning and Creativity. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleNaveed, Muhammad Asif, Javed Iqbal, Muhammad Zaheer Asghar, Rozeen Shaukat, and Pirita Seitamaa-hakkarainen. 2023. "Information Literacy as a Predictor of Work Performance: The Mediating Role of Lifelong Learning and Creativity" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13010024

APA StyleNaveed, M. A., Iqbal, J., Asghar, M. Z., Shaukat, R., & Seitamaa-hakkarainen, P. (2023). Information Literacy as a Predictor of Work Performance: The Mediating Role of Lifelong Learning and Creativity. Behavioral Sciences, 13(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13010024