Training of Faculty and Staff in Recognising Undergraduate Medical Students’ Psychological Symptoms and Providing Support: A Narrative Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Faculty/Staff’s Awareness and Acknowledged Importance of Recognising Students’ Psychological Problems

3.2. Faculty/Staff’s Perceived Preparedness

3.3. The Effectiveness of Training

4. Critical Appraisal of the Articles Reviewed

5. Discussion

- -

- What are the reasons for the high mental illness among medical students?

- -

- What are the mental health needs of medical students and what training for faculty and staff can address students’ needs?

- -

- Is this training effective? Does it help faculty and staff gain confidence and skills in order to recognise students’ psychological symptoms and provide support?

- -

- Does the training help students’ deal with their psychological symptoms and help them develop as learners and professionals later on?

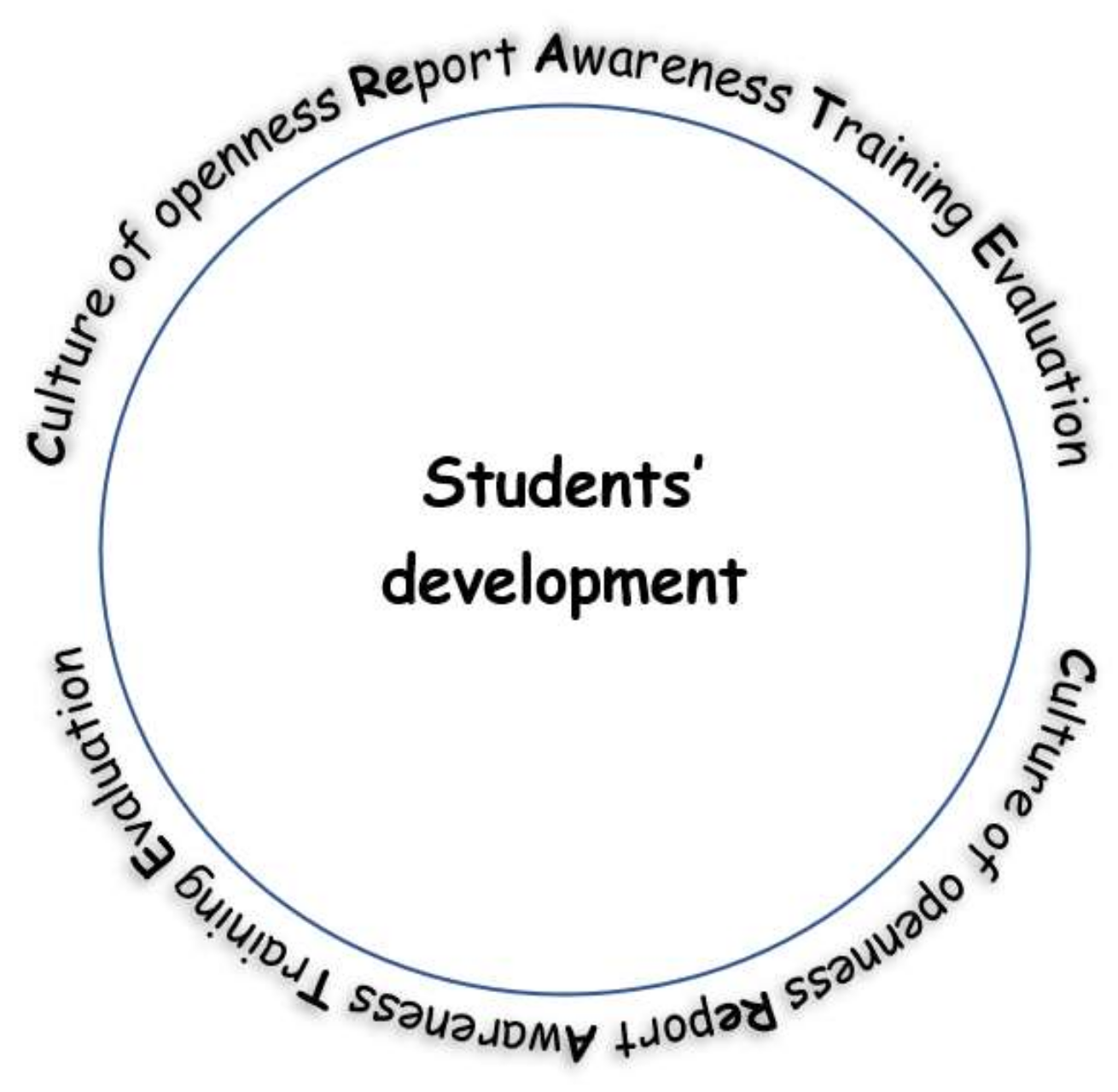

The CReATE Circle

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- British Medical Association. Medical Students Must Be Given Better Mental Health Support to Prepare Them for Emotional Toll of Career in the NHS. 2018. Available online: https://www.bma.org.uk/news/media-centre/press-releases/2018/june/medical-students-must-be-given-better-mental-health-support (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- Rotenstein, L.S.; Ramos, M.A.; Torre, M.; Segal, J.B.; Peluso, M.J.; Guille, C.; Sen, S.; Mata, D.A. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2016, 316, 2214–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karp, J.F.; Levine, A.S. Mental health services for medical students-time to act. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 1196–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billingsley, M. More than 80% of medical students with mental health issues feel under-supported, says Student BMJ survey. Stud. BMJ 2015, 351, h4521. Available online: http://student.bmj.com/student/view-article.html?id=sbmj.h4521 (accessed on 2 August 2021). [CrossRef]

- Azim, S.R. Mental Distress among Medical Students. In Anxiety Disorders-The New Achievements; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Chen, R.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Deng, W. Prevalence of mental health problems among medical students in China: A meta-analysis. Medicine 2019, 98, e15337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maser, B.; Danilewitz, M.; Guérin, E.; Findlay, L.; Frank, E. Medical student psychological distress and mental illness relative to the general population: A Canadian cross-sectional survey. Acad. Med. 2019, 94, 1781–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slavin, S.J.; Schindler, D.L.; Chibnall, J.T. Medical student mental health 3.0: Improving student wellness through curricular changes. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janoušková, M.; Weissová, A.; Formánek, T.; Pasz, J.; Motlová, L.B. Mental illness stigma among medical students and teachers. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2017, 63, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazeau, C.M.; Shanafelt, T.; Durning, S.J.; Massie, F.S.; Eacker, A.; Moutier, C.; Satele, D.V.; Sloan, J.A.; Dyrbye, L.N. Distress among matriculating medical students relative to the general population. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1520–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinou, C.; Georgiades, S.; Papageorgiou, A. PEACE of mind: Guidelines for enhancing psychological support for medical students. MedEdPublish 2020, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, D.; Hunt, J.; Speer, N. Help Seeking for Mental Health on College Campuses: Review of Evidence and Next Steps for Research and Practice. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2012, 20, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, H.R. What constitutes a good literature review and why does its quality matter? Environ. Model. Softw. 2013, 43, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paré, G.; Kitsiou, S. Methods for Literature Reviews. In Handbook of Ehealth Evaluation: An Evidence-Based Approach; Lau, F., Kuziemsky, C., Eds.; University of Victoria: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2016; pp. 157–180. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, R. Writing narrative style literature reviews. Med. Writ. 2015, 24, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baethge, C.; Goldbeck-Wood, S.; Mertens, S. SANRA—A scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2019, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalkbrenner, M.T.; Jolley, A.L.; Hays, D.G. Faculty views on college student mental health: Implications for retention and student success. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. Res. Theory Pract. 2021, 23, 636–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sontag-Padilla, L.; Dunbar, M.S.; Seelam, R.; Kase, C.A.; Setodji, C.M.; Stein, B.D. California community college faculty and staff help address student mental health issues. Rand Health Q. 2018, 8, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, L.J. Striving to Help College Students with Mental Health Issues. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Heal. Serv. 2007, 45, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margrove, K.; Gustowska, M.; Grove, L. Provision of support for psychological distress by university staff, and receptiveness to mental health training. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2012, 38, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardekani, A.; Hosseini, S.A.; Tabari, P.; Rahimian, Z.; Feili, A.; Amini, M.; Mani, A. Student support systems for undergraduate medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic narrative review of the literature. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rau, T.; Plener, P.; Kliemann, A.; Fegert, J.M.; Allroggen, M. Suicidality among medical students—A practical guide for staff members in medical schools. GMS Z. Fur Med. Ausbild. 2013, 30, Doc48. [Google Scholar]

- Spear, S.; Morey, Y.; van Steen, T. Academics’ perceptions and experiences of working with students with mental health problems: Insights from across the UK higher education sector. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2020, 40, 1117–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvara, A.L.; Mandracchia, J.T. An investigation of gatekeeper training and self-efficacy for suicide intervention among college/university faculty. Crisis 2019, 40, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipson, S.K.; Talaski, A.; Cesare, N.; Malpiede, M.; Humphrey, D. The Role of Faculty in Student Mental Health; Boston University, Mary Christie Foundation and The Healthy Minds Network: Boston, MA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://marychristieinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/The-Role-of-Faculty-in-Student-Mental-Health.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Gulliver, A.; Farrer, L.; Bennett, K.; Griffiths, K. University staff mental health literacy, stigma and their experience of students with mental health problems. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2017, 43, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, N.; Suzuki, Y.; Kato, T.A.; Fujisawa, D.; Sato, R.; Aoyama-Uehara, K.; Fukasawa, M.; Asakura, S.; Kusumi, I.; Otsuka, K. Effectiveness of suicide prevention gatekeeper-training for university administrative staff in Japan. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 70, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, N.; Takeda, H.; Fujii, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Kato, T.A.; Fujisawa, D.; Aoyama-Uehara, K.; Otsuka, K.; Mitsui, N.; Asakura, S.; et al. Effectiveness of suicide prevention gatekeeper training for university teachers in Japan. Asian J. Psychiatry 2021, 60, 102661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinzow, H.M.; Thompson, M.P.; Fulmer, C.B.; Goree, J.; Evinger, L. Evaluation of a brief suicide prevention training program for college campuses. Arch. Suicide Res. 2020, 24, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, E.; Martins, N. An organisational culture model to promote creativity and innovation. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2002, 28, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Inclusion | Peer-reviewed articles or chapters |

| Theses and dissertations | |

| Literature reviews | |

| Conference papers | |

| Editorials | |

| Books or textbooks | |

| All of the above that include or discuss training of faculty and staff in recognising students’ psychological symptoms in tertiary education | |

| Published in English | |

| Period of publication: 2000–2021 | |

| Exclusion | Peer-review articles, chapters, theses or dissertations, conference papers, editorials, books and textbooks that do not include or discuss training of faculty and staff in recognising students’ psychological symptoms in tertiary education and providing support |

| Any of the above publications published before 2000 | |

| Published in languages other than English |

| Has the need for training faculty and staff in recognising undergraduate medical students’ psychological symptoms and providing support been assessed and documented? |

| What are the faculty/staff’s views on recognising medical students’ psychological symptoms and providing support? |

| Is there any training of faculty and staff in recognising undergraduate medical students’ psychological symptoms and providing support? Is there such training in other disciplines in tertiary education? |

| What did this training entail? |

| Has this training been effective in terms of enhancing faculty and staff’s skills and confidence? |

| Has this training been effective in terms of identifying psychological symptoms early and helping students? |

| Has this training shown any long-term effects? |

| References Number | Article | Key Results | Limitations | Suitability of the Methods Used to Test the Initial Hypothesis/Aims | Quality of the Results Obtained | Interpretations of the Results | Impact of the Conclusions on the Field |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [12] | Eisenberg, D., Hunt, J., & Speer, N. (2012). Help Seeking for Mental Health on College Campuses: Review of Evidence and Next Steps for Research and Practice. Harvard Review Of Psychiatry, 20(4), 222–232. https://doi.org/10.3109/10673229.2012.712839 | Most college students with mental health problems are not receiving treatment. Wide range of factors influence students’ help seeking for mental illnesses; traditional barriers (knowledge and stigma) not the only reasons (many untreated students do not have deep-rooted attitudes that prevent them from receiving treatment). Most common intervention strategies to address help seeking on college campuses categorized into three groups: - stigma reduction and education campaigns - screening and linkage programs - gatekeeper training | It is not clear what methodology has been used for searching and reviewing the evidence. | Review study addresses the study objective: advance our thinking about how to increase use of appropriate services among college students with significant mental health problems. | Results are well presented and reveal what is known about help-seeking behaviour and what can be done in the future to increase the number of students who receive intervention. | New strategies may prove to be important for changing behaviour of large numbers of students who are not using services. Seeking help for mental health involves short-term costs (e.g., time, energy, money) with expectation of better health in future. | New approaches to help seeking in college setting need to be explored. More effective overall set of strategies will yield great benefits to young people (will also benefit society). |

| [18] | Kalkbrenner, M.T., Jolley, A.L. and Hays, D.G., 2019. Faculty views on college student mental health: Implications for retention and student success. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, p.1521025119867639. | Knowledge of MHD definition as a combination of genetic and environmental factors. Knowledge of warning signs as changes in behaviour. Comfort and willingness to recognize and refer was impacted by personal experiences and the stigma in college environment. Limited knowledge about resources for mental health issues (not specifically aware of services provided or philosophies held by college counselling centre). Faculty-student relationships influenced level of comfort associated with reaching out to students about MHDs and also the classroom context (harder to recognize MHDs in large lecture hall). | Results may not be generalisable to all faculty members. Security of tenure amongst two participants may have influenced their comfort in supporting student mental health. Three participants trained in mental-health- related fields that may have influenced their perceptions on MHDs. Self-selection bias. Snowball sampling procedure (recruiting participants from similar academic departments). | Phenomenological Study: Allowed researchers to explore the experiences of faculty members and address the two research questions: - How do faculty members who have lived experiences with supporting college student mental health conceptualize MHDs among college students? - What contextual variables relate to their likelihood to refer students with mental health symptoms to university resources? | Qualitative Data: Explores more in-depth how faculty members conceptualize and recognize MHDs, along with factors that influence the degree to which they provide accommodations. Results clearly presented in five emergent themes that addressed the research questions. | Faculty knowledge of MHDs and warning signs (behaviour changes) showcases the importance of utilizing faculty members as resources to identify students with MHDs who might not seek out services. Limited knowledge about resources for mental health issues suggests that faculty members have an ade quate awareness of the general availability of university resources; however, many did not have knowledge about specific services | Faculty have a responsibility to support student mental health. Recommended: - Awareness and Education about College Counselling Centre - Unification of Campus Resources and Policy - Structuring the Academic Environment - Advocacy for College Counselling Centres |

| [19] | Sontag-Padilla, L., Dunbar, M.S., Seelam, R., Kase, C.A., Setodji, C.M. and Stein, B.D., 2018. California community college faculty and staff help address student mental health issues. Rand health quarterly, 8(2). | Community college students experience mental health challenges and adverse circumstances (e.g., homelessness) that put them at risk for ongoing problems. Most faculty and staff acknowledge concerns about the mental health of students on their campuses, and many take action to help students with mental health needs. Most faculty and staff surveyed in 2017 held favourable views of their campuses’ student mental health services, with positive perceptions increasing since 2013. Just over half of faculty and staff surveyed reported that their campuses are actively putting into place training programs to help faculty and staff recognise and respond to students with mental health needs. In the six months prior to the survey, only a quarter of faculty and staff participated in training on how to better support students with mental health problems. Continued efforts are needed to ensure that faculty and staff are equipped to address student mental health issues on campus. | Selection Bias (Not all campuses invited all faculty and staff to participate). Self-Reported Data (No objective information). | Survey collecting quantitative data in regard to the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours of faculty and staff in regard to supporting mental health needs of students. | Results of the survey addressed all three aims: - Campus experiences and attitudes related to student mental health - Perceptions of how campuses are serving students’ mental health needs - Perceptions of the overall campus climate toward student mental health and wellbeing Promising findings but still shows that there is room for improvements for faculty and staff. Results clearly presented in tables. | Most faculty and staff acknowledge concerns about mental health of students on campuses and take action to help students with mental health needs. Most staff had concerns about their ability to help students, hence suggesting that they need to continue to provide staff with resources so they can become more confident in helping their students. | Faculty and staff members should participate in training (online seminars, individualized programs, group sessions) to ensure they feel more confident in their abilities to help students with their mental health needs. |

| [20] | Cook, L.J., 2007. Striving to help college students with mental health issues. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 45(4), pp. 40–44. | The severity and number of mental health problems is increasing among college students across the United States. Psychiatric mental health nursing faculty can work to develop support systems for students with mental health problems through the establishment of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) on campus programs, which provide advocacy, education, and support to students with mental health issues. Psychiatric mental health nursing faculty can incorporate NAMI activities and suicide awareness and prevention programs for the college campus into various courses that address mental health issues and involve faculty and students from other disciplines.Seeking grants to develop education, advocacy, and student support activities is another way psychiatric nursing faculty can improve mental health programs on college campuses. | Viewpoint of the efforts of one psychiatric mental health nursing faculty member. | Review of programs to help reach students with mental health needs through establishment of on-campus NAMI through discussion of establishment goals and past accomplishments to help. | Through discussion of research articles, the author showcases the increasing need of services to address mental health needs. | Mental health nursing faculty can help address problems on college campuses by offering courses on mental health issues and skills. | Mental health problems in college are increasing in number and severity and many people are not willing to seek help, there is a need for additional staff and programs that are able to help students in need. |

| [21] | Margrove, K., Gustowska, M., & Grove, L. (2012). Provision of support for psychological distress by university staff, and receptiveness to mental health training. Journal Of Further And Higher Education, 38(1), 90–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877x.2012.699518 | Most staff participating in this research had experience of providing support for psychological distress. Over half of the staff participants indicated that they felt more training in mental health could benefit them. Most survey respondents were aware of signs of major depression and schizophrenia, and many could detect that normal troubles were not likely to be an indication of a mental health problem. | Research confined to staff from one type of faculty. Participants’ views about what constitutes psychological distress may have varied. | Anonymous online survey to identify whether staff provided support for psychological distress to students and colleagues and to see whether staff are trained in mental health issues. Survey included optional free-text space allowing participants chance to comment on mental health training in workplace (included in case participants wanted to say something that was not addressed by other quantitative questions). | Both quantitative and qualitative results presented clearly and addressed research aims. | High levels of psychological distress in students could be placing additional demands on university staff working in both administrative/support or academic roles. | Higher education institutions should introduce training for their employees with experienced and qualified mental health training providers. Further qualitative research should be completed to help shed light on issues in greater depth. |

| [22] | Ardekani, A. et al., 2021. Student support systems for undergraduate medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic narrative review of the literature. BMC Medical Education, 21(1). | “Taken together, the results of our review assert that methods of supporting medical students should be adapted to the new circumstances and environments and should provide different levels of support through both online and in-person strategies” | There are no randomized control trials or high-quality interventions on the efficiency of support systems devised in response to COVID-19. There are currently a small number of studies that fit the research criteria. The included studies focused on describing their methods rather than evaluating the outcomes. | The studies included were reviewed and underwent critical appraisal. Though none of the chosen studies were excluded after being found to be low quality. | None of the included studies met the criteria (7 out of 11 items checked against the Buckly et al. criteria) to be considered high-quality studies. | Most studies tend to describe the educational intervention rather than evaluating its outcomes. Methods of supporting students should be adapted to new circumstances and environments. Support should be offered through both in person and online strategies | Future research should focus on evaluating the outcomes of intervention strategies. |

| [23] | Rau, T., Plener, P., Kliemann, A., Fegert, J. M., & Allroggen, M. (2013). Suicidality among medical students–a practical guide for staff members in medical schools. GMS Zeitschrift fur medizinische Ausbildung, 30(4), Doc48. | Risk factors for suicidal behaviour among medical students—fear, depression, negative life experiences, impulsivity, female gender, physical discomfort, low SES, low quality of life, perceived level of stress, developmental crises, and difficulties separating from parents. Indicators of increased suicide risk—presenting with suicidal thoughts, risk factors, current stressful situations, psychopathological conspicuities that show themselves as hopelessness, fear, anxiousness, irritation. Recognizing suicidality by staff members—students expressing feelings of being overwhelmed, pressured, overburdened, radiate hopelessness, sadness, abrupt change in behaviour, increased absence. Staff should approach the topic of suicidality in the context of a conversation, show understanding, signal willingness to support, offer help/assistance where possible. Have additional meetings set up. Scenarios: Suicidal thoughts are not yet present but when student’s express feelings of excessive stress and hopelessness—professional help Expressing suicidal thoughts—specific and immediate risk needs to be decided. Intentions to act are being communicated— immediately seen by psychiatrist, ER Providing expert training workshops— Participants showed significant increase in their level of knowledge and confidence in their own competence to act when pre- and post-training data were compared. | Literature review—causation cannot be made. Assessing suicidality in different studies that have differing methodological approaches, composition of samples (age, year of study, gender proportionality), and cultural context. Confounding variables—complex interplay between factors | Literature review. Aims—describe the epidemiology and factors leading to suicidality in medical students and demonstrate options for handling suicidal crises in students. | Article search published between 1993–2013 via Ovid using the data bases Medlin and PsycINFO. | Suicidal thoughts are more prevalent among medical students than in the general population of comparable age group. Staff members should have adequate training and gain basic knowledge and skills in dealing with the issue of suicidality to be better prepared and have increased confidence and competence in confronting risk situations. Expert training enables staff to become more sensitive in recognizing and dealing with at risk students and to provide them with practical competences to act effectively in such situations. | Helps raise awareness of suicidality among students, demonstrate effective strategies, and training needed for handling suicidal crises. Such training programs can provide a crucial contribution to suicide prevention at universities. |

| [24] | Spear, S., Morey, Y. & van Steen, T., 2020. Academics’ perceptions and experiences of working with students with mental health problems: Insights from across the UK higher education sector. Higher Education Research & Development, 40(5), pp.1117–1130. | Nearly all respondents (96%) had encountered student mental health problems (MHP) amongst their students (n = 130). This was true across each institution type: Russell group—92%, pre-1992 group—97%, post 1992 group—98% Respondents’ awareness of student MHPs was high but the preparedness to support students was low. 31% felt their current institution adequately prepared them for working with students. 56% had not received training in working with students MHP. | A limited number of respondents and the self-selecting nature of the survey selected for participants that already had some interest in student mental health. It did not allow for a reach to staff with less interest, which would have given a more holistic understanding of staff perception and student experiences. The study focuses on academics with any teaching or supervision responsibilities. A more focused study on specific student groups and academics would highlight problems those groups face. There was a low response rate from institutions and academics, so it is not a representative sample of UK universities. The study focused on mental health problems in one national context (UK). | The use of a quantitative first phase and a qualitive second phase allowed for a more comprehensive investigation into the main study aim. | The sample size of the study was small. | 96% of all the staff that responded to the survey had encountered MHP in their students. Students often turn to academic staff for initial and ongoing support as they have most contact with these staff and are likely to trust them most. | Academic staff should be an integral part of any institutions strategy for enhancing student mental health. |

| [25] | Sylvara, A. L., & Mandracchia, J. T. (2019). An investigation of gatekeeper training and self-efficacy for suicide intervention among college/university faculty. Crisis. | Most participants reported believing it is the college/university faculty’s role to identify students at risk for suicide; however, many reported that their institution did not provide gatekeeper training. Participants who had received gatekeeper training were more confident in identifying and assisting at-risk students. | The study did not include demographics (sex, type of institution, department of faculty, state of residence). Participants knowledge of their institutions’ policies and procedures relating to referring and intervening with a student who presents as suicidal (which was the purpose of the study) was not directly evaluated but the participants belief on how familiar they were with the policies was evaluated instead. The participants were not asked whether they had been trained in suicide prevention or intervention before. | The methods accurately investigated the study’s aims. | The study used 6 t-tests to assess the tested outcomes. The results were accurately assessed and proved to be statistically significant were reported. | Faculty should be trained in assisting at-risk students so that they can develop more confidence and better refer at-risk students. | Training faculty to assess and respond to at-risk students may decrease suicide deaths among college/university students. |

| [26] | Lipson, S. K., Talaski, A., Cesare, N., Malpiede, M., & Humphrey, D. (2021). The role of faculty in student mental health. Boston University, Mary Christie Foundation and The Healthy Minds Network. | 87% of faculty believe that student mental health has “worsened” or “significantly worsened” during the COVID-19 pandemic. Almost 80% have had one-on-one phone, video, or email conversations with students in the past 12 months regarding student mental health and wellness. Only 51% of faculty reported that they have a good idea of how to recognize that a student is in emotional or mental distress. 73% would welcome additional professional development on the topic of student mental health. 61% believe it should be mandatory that all faculty receive basic training in how to respond to students experiencing mental or emotional distress. 21% of faculty agree that supporting students in mental and emotional distress has taken a toll on their own mental health. Half believe their institution should invest more in supporting faculty mental health and wellbeing. | Selection bias—university staff members self-selected to participate in the study. | Aim—understanding faculty members’ perceptions of student mental health needs, faculty’s experiences supporting students, and the need for institutional resources to address both student and faculty mental health. | Survey responses from 1685 faculty members at 12 colleges and universities across the United States | Majority of faculty members would welcome more training in how to support students experiencing mental health issues and believe that this training should be mandatory. | Universities can do a better job in supporting faculty in addressing the mental health of all students. |

| [27] | Gulliver, A., Farrer, L., Bennett, K. and Griffiths, K., 2017. University staff mental health literacy, stigma and their experience of students with mental health problems. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 43(3), pp. 434–442. | Teachers with higher levels of depression literacy were more likely to engage with students with mental health problems and felt sufficiently informed to help. Higher levels of stigmatising attitudes to depression did not independently predict whether a teaching staff member would approach a student to assist with a mental health problem. Stigmatising attitude did not impact on a staff member’s willingness to approach a student to assist with mental health problems. | Selection bias—university staff members self-selected to participate in the study. The sample comprised a single university, and thus may not be representative of all university staff. Only attitudes and knowledge related to one common mental disorder were assessed (depression), staff could have had more knowledge of or demonstrated more stigmatising attitudes to other mental health problems. | Aim—to identify if university staff attitudes to and knowledge about mental health problems, or whether these factors influence their experience with and assistance of students with mental health problems. Measures—university staff literacy, the stigma they attach to depression, and the influence of these factors on their experience with and assistance of students with mental health problems. | 224 teaching staff members at Canberra University completed an anonymous online survey via an email link that featured a series of questions adapted from Reinke et al. (2011) involving— demographics, professional information, experiences with student mental health, knowledge of depression (literacy) and attitudes to depression (stigma). | University staff may be unlikely to allow personal beliefs to interfere with their professional judgement. | Ensuring staff complete mental health literacy training and have adequate skills to respond appropriately to students with mental health problems may help in connecting young people to appropriate care in a university context. University staff members are well positioned to offer an initial point of contact for referral to appropriate sources of professional help. |

| [28] | Hashimoto, N., Suzuki, Y., Kato, T. A., Fujisawa, D., Sato, R., Aoyama-Uehara, K., … & Otsuka, K. (2016). Effectiveness of suicide prevention gatekeeper-training for university administrative staff in Japan. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 70(1), 62–70. | A significant improvement in competence in the management of suicidal students was found. These improvements continued for a month. About 95% of the participants (n = 76) rated the program as useful or very useful and one-third of the participants had one or more chances to utilize their skills within a month. | There was no control arm in the study. The participants were individually selected, which allows for some selection bias. The long-term effectiveness of the study was not tested. The study was carried out in one institution with administrative staff only so the results cannot be generalized. The effects of the interventions on students were not evaluated. The participants already had relatively positive views before the training. The participants ratings were on a single scale and not validated, therefore, making further inferences might not be appropriate. | The study accurately tested the study aims. | The improvements in confidence and management were measured as a single-scale self-reported outcome and thus could not be validated. The results were all assessed using the appropriate statistical measures and the study itself was ethically sound. The self-reported nature of the results decreased the validity and reliability. | There were significant improvements in competence and confidence in managing suicidal students, as well as improvements in the behavioural intention of the teachers for a month following the training. This would suggest the usefulness of the program for improving participants’ attitudes. | Training programs shown to be effective even in areas where there is a positive view on MHP that students may face. The research should focus on student outcomes in the future. |

| [29] | Hashimoto, N., Takeda, H., Fujii, Y., Suzuki, Y., Kato, T. A., Fujisawa, D., … & Kusumi, I. (2021). Effectiveness of suicide prevention gatekeeper training for university teachers in Japan. Asian journal of psychiatry, 60, 102661. | Eighty-one (81) university teachers were trained, 63 had a 1 h mental health lecture and 18 received the authors’ gatekeeper training. The Suicide Intervention Response Inventory (SIRI) was used for measuring the management of students with suicidal thoughts. The two groups were compared. The participants who received the gatekeeper training were more confident and had better skills. | No follow-up measurement was carried out and the authors could not determine how long the effects lasted. Also, the authors did not assess behavioural change. The training could have been longer in order to have greater impact on behavioural change. | The methodology was quantitative and compared two groups who had received different types of training. It was not clear if this was a randomised control trial as the groups were not randomly selected and the participants did not complete questionnaires before and after but only after the trainings. | The results were statistically analysed and presented in detail in a table, showing statistical significance. | Results showed that focused training can help university teachers gain more confidence and competence regarding recognising the students who are at risk of suicide. This is important provided that mental illness and suicidal ideation are high among university students. | The study filled in an identified gap in the literature because the authors’ previous study was conducted with staff, and they aimed to explore the situation with university teachers. |

| [30] | Zinzow, H. M., Thompson, M. P., Fulmer, C. B., Goree, J., & Evinger, L. (2020). Evaluation of a brief suicide prevention training program for college campuses. Archives of suicide research, 24(1), 82–95. | Students exhibited a greater increase in gatekeeper behaviour, in comparison to non-students. Large changes were observed on publicizing suicide prevention information and having informal conversations about suicide with students, and 76% had engaged in gatekeeper behaviour at follow-up. Declines on knowledge and self-efficacy from post-test to follow-up highlight the importance of booster sessions and complementary programming. | There is a lack of comparison groups hindering the ability to draw causal conclusions in regard to the impact of the training on the study outcomes. A larger scale of participants is needed (faculty and staff) to fix the discrepancies between the training groups. Most of the student participants were resident assistants (RAs). This may limit the ability to generalize to broader student populations as RAs hold a greater responsibility and may apply the practice skills at a greater frequency. There was a lack of demographic information (race, age, gender) that hinders the ability to determine if the training’s effectiveness varies between the different demographics. The knowledge and self-efficacy measure appeared to be assessing a large number of factors with a small number of items. | The methods accurately explored the aims of the study. | The study followed proper ethical protocols. They incorporated suitable statistical tests (repeated measure ANOVAS) to calculate their data, the calculations to the datasets were also provided. The data and findings were valid and had high reliability. | Findings offer support for the potential efficacy of a brief prevention program, with promising effects on several suicide prevention behaviours. | Widespread participation from students and employees on college campuses could be the next step in suicide prevention training and prevention strategies. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Constantinou, C.S.; Thrastardottir, T.O.; Baidwan, H.K.; Makenete, M.S.; Papageorgiou, A.; Georgiades, S. Training of Faculty and Staff in Recognising Undergraduate Medical Students’ Psychological Symptoms and Providing Support: A Narrative Literature Review. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 305. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12090305

Constantinou CS, Thrastardottir TO, Baidwan HK, Makenete MS, Papageorgiou A, Georgiades S. Training of Faculty and Staff in Recognising Undergraduate Medical Students’ Psychological Symptoms and Providing Support: A Narrative Literature Review. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(9):305. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12090305

Chicago/Turabian StyleConstantinou, Costas S., Tinna Osk Thrastardottir, Hamreet Kaur Baidwan, Mohlaka Strong Makenete, Alexia Papageorgiou, and Stelios Georgiades. 2022. "Training of Faculty and Staff in Recognising Undergraduate Medical Students’ Psychological Symptoms and Providing Support: A Narrative Literature Review" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 9: 305. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12090305

APA StyleConstantinou, C. S., Thrastardottir, T. O., Baidwan, H. K., Makenete, M. S., Papageorgiou, A., & Georgiades, S. (2022). Training of Faculty and Staff in Recognising Undergraduate Medical Students’ Psychological Symptoms and Providing Support: A Narrative Literature Review. Behavioral Sciences, 12(9), 305. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12090305