Role of Jumpstart Nutrition®, a Dietary Supplement, to Ameliorate Calcium-to-Phosphorus Ratio and Parathyroid Hormone of Patients with Osteoarthritis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment of Patients

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Design

2.4. Evaluation of Knee-Injury Osteoarthritis Outcome Scale

2.5. Evaluation of Karnofsky Performance Scale

2.6. Evaluation of Biochemical Parameters

2.7. Evaluation of Pearson’s Correlation Coefficients between Two Biomarkers

2.8. Evaluation of Radiological Images with the Kellgren-Lawrance Grading Scale

2.9. Management of Supplement Studies

- As the supplements are not drugs, they are not prescribed but are recommended for the improvement of the levels of calcium, phosphorus, vitamin D, and parathyroid hormone during the management of OA.

- The supplement is used in addition to the best management/ care, if available, based on appropriate international guidelines.

- There is no interference with any other treatment or preventive measure while using the supplement.

- A register is always maintained for the evaluation of these studies.

- The supplement is not very costly and easily available on the market without prescription.

- The patients considered as experimental subjects were those who have consumed the supplement continuously for eight weeks as per register.

- A possible placebo effect is explained, and no placebo is used.

- Safety and tolerability were strictly evaluated.

2.10. External Study Reviewers

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

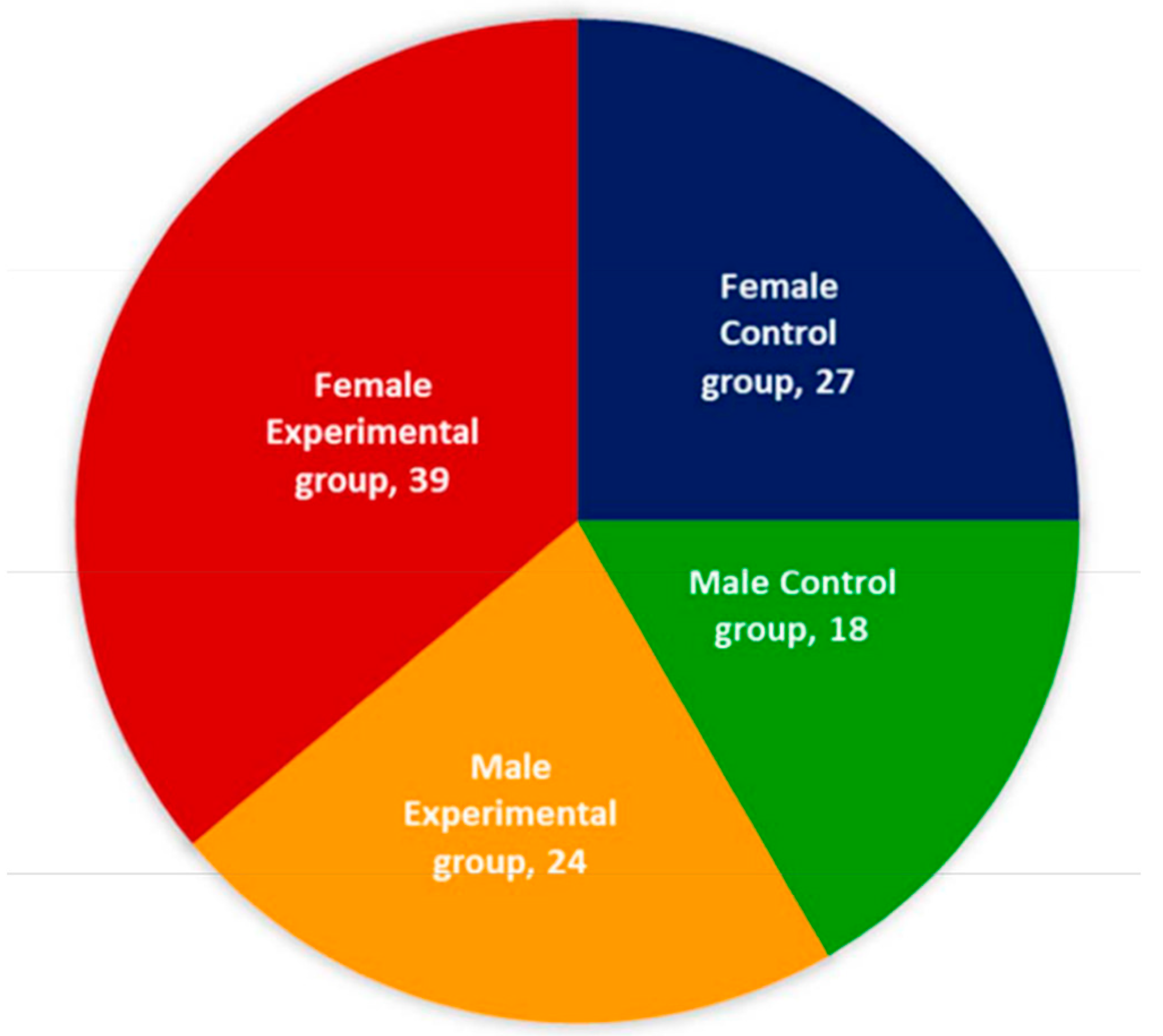

3.1. Enrolment and Baseline Characteristics of Patients

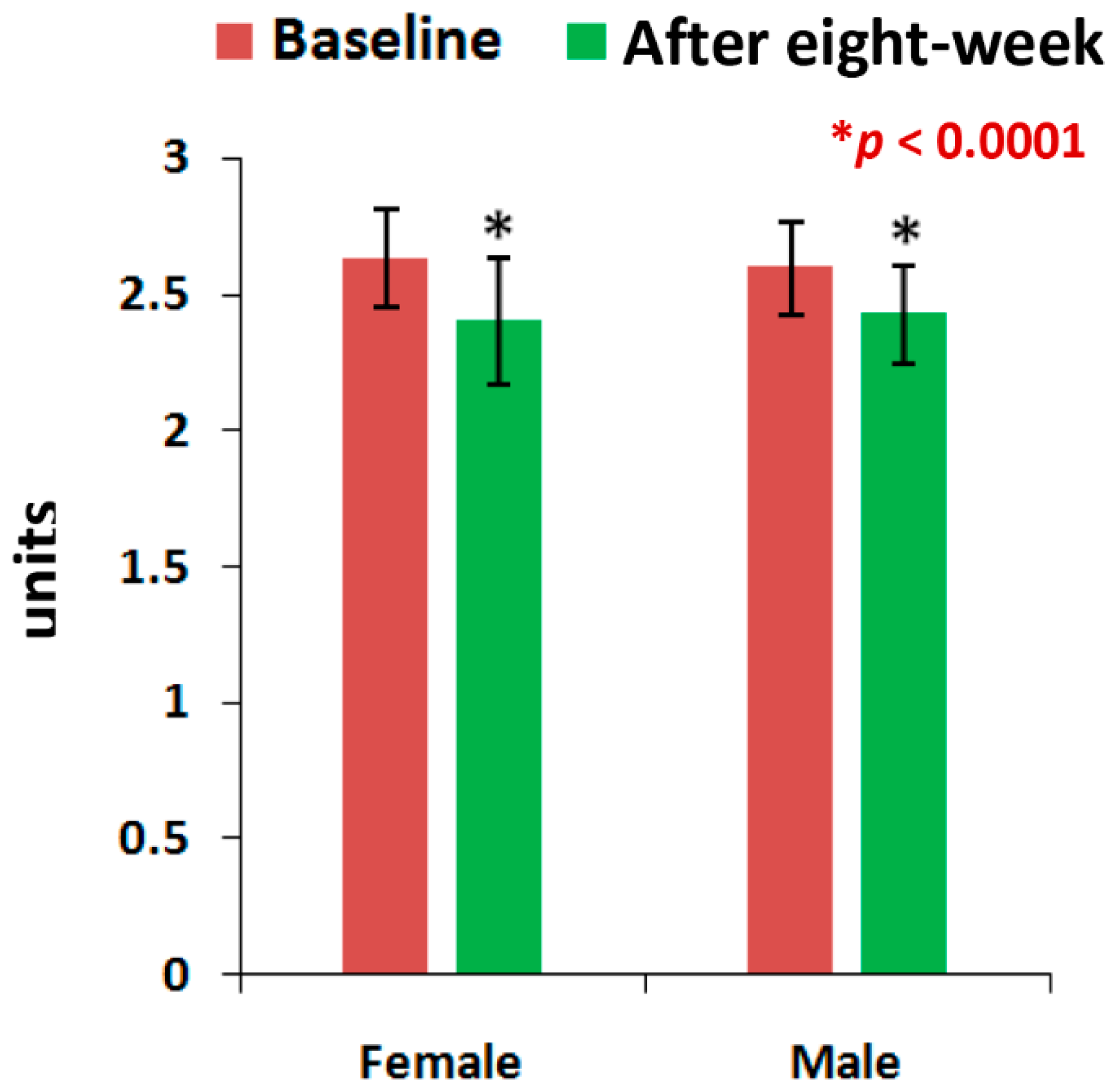

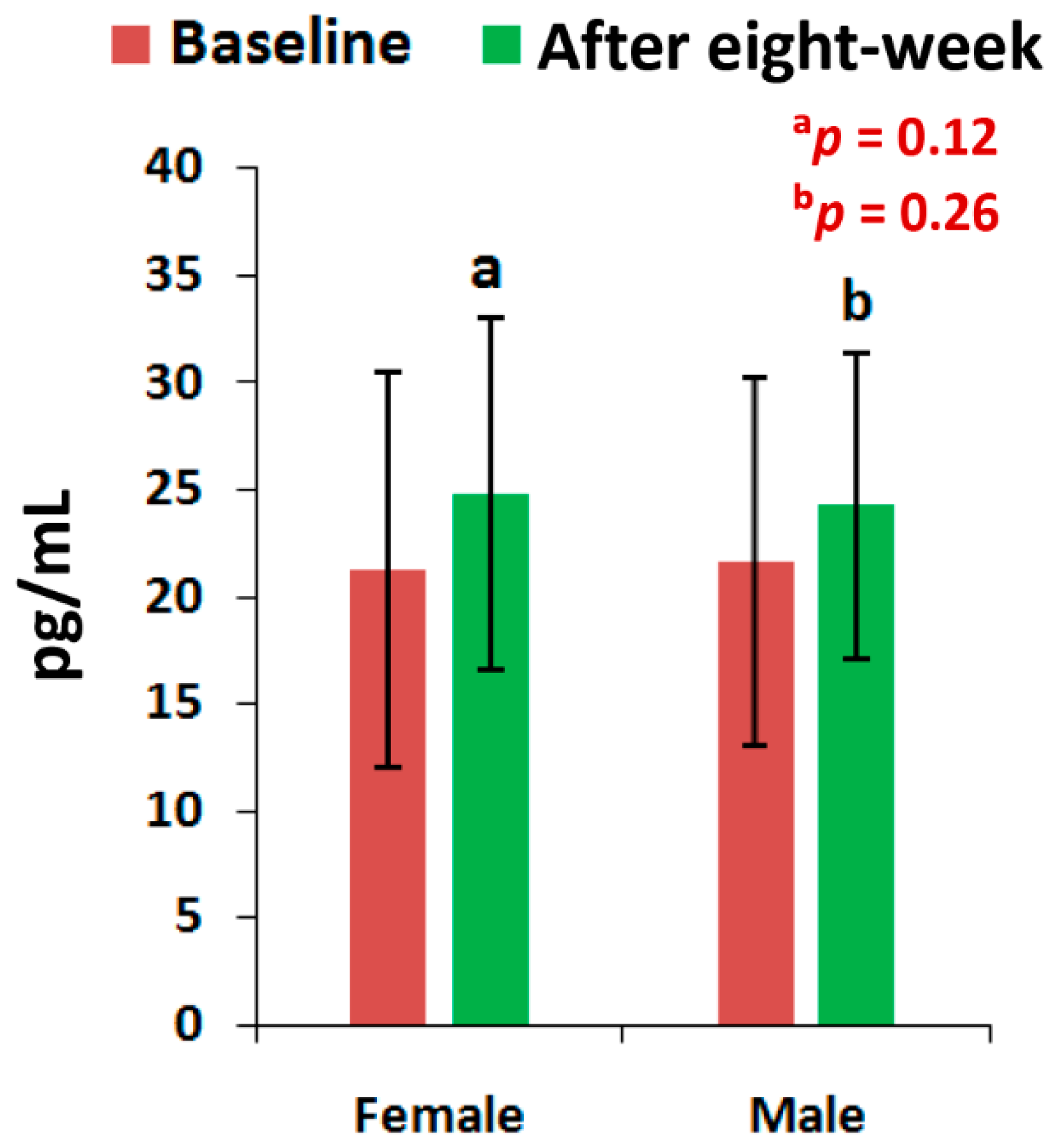

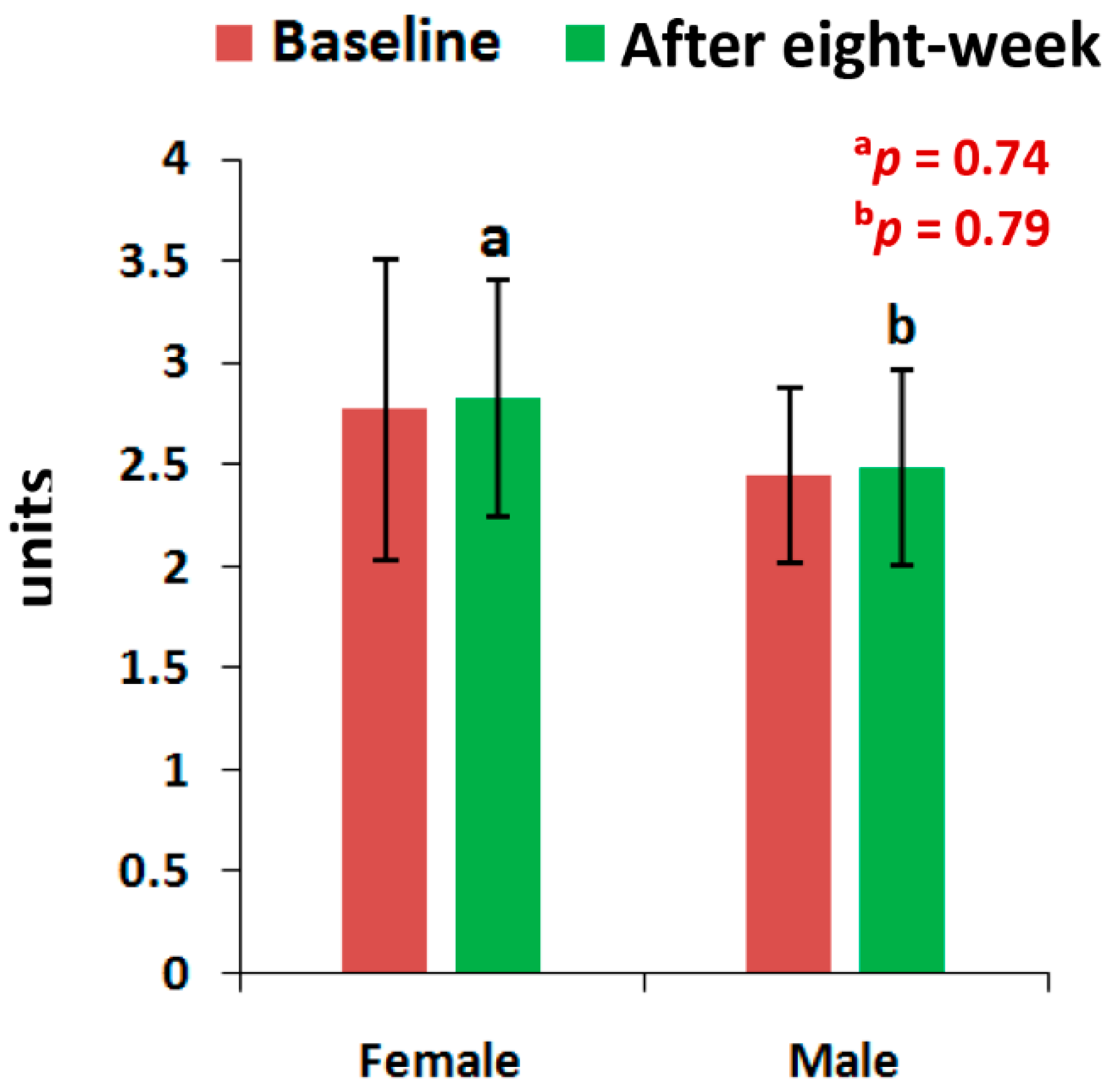

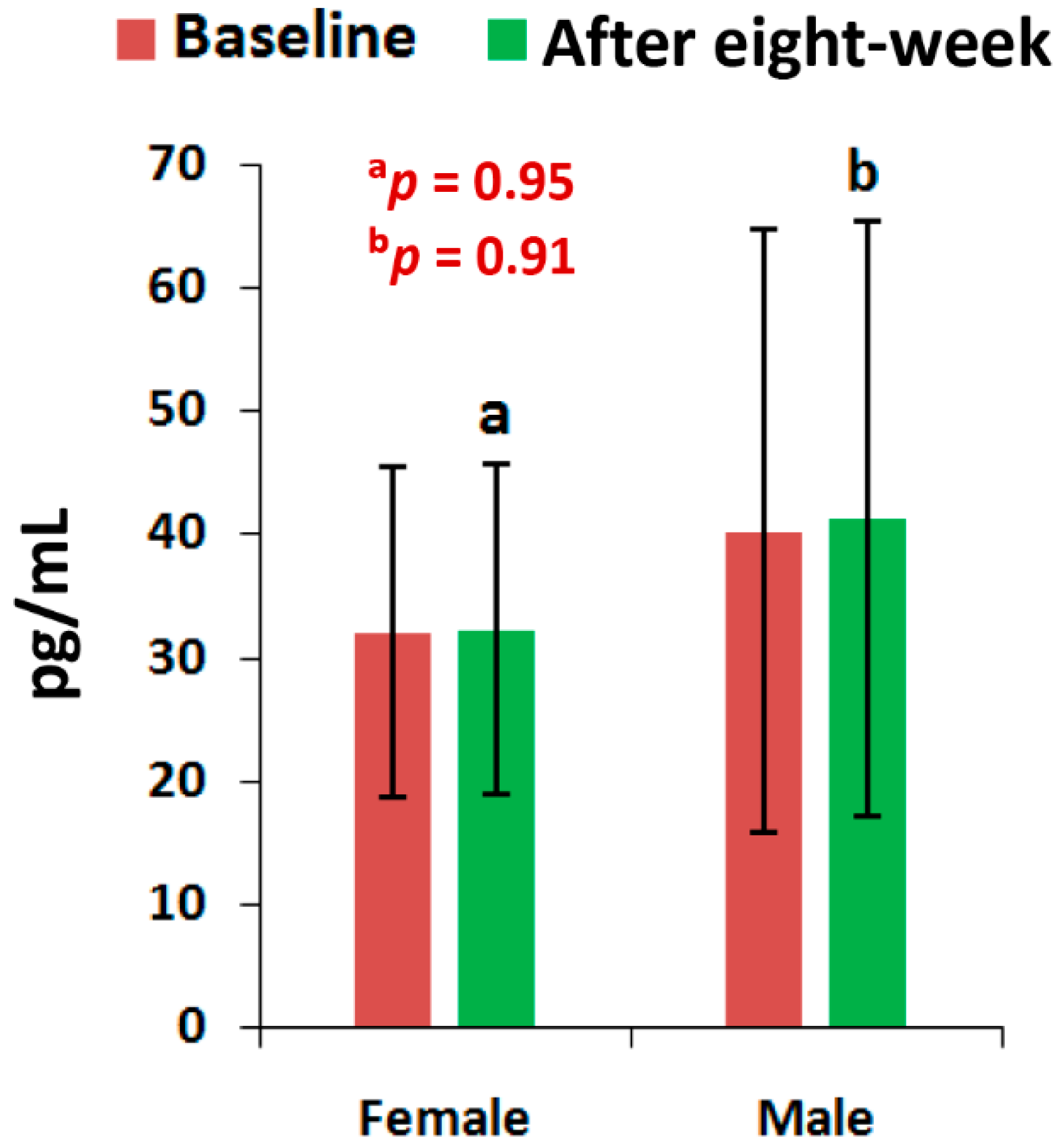

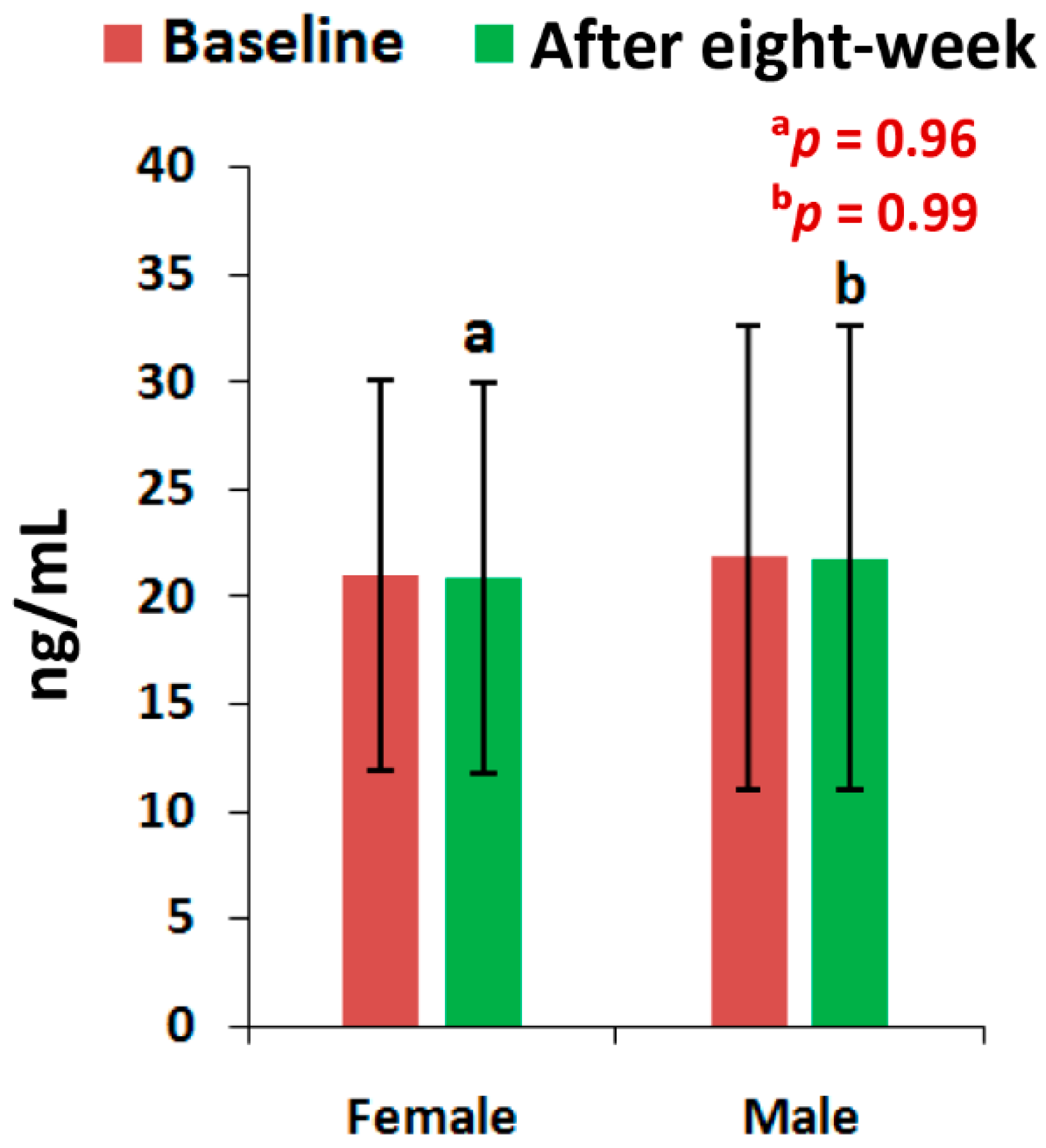

3.2. Biochemical Parameters

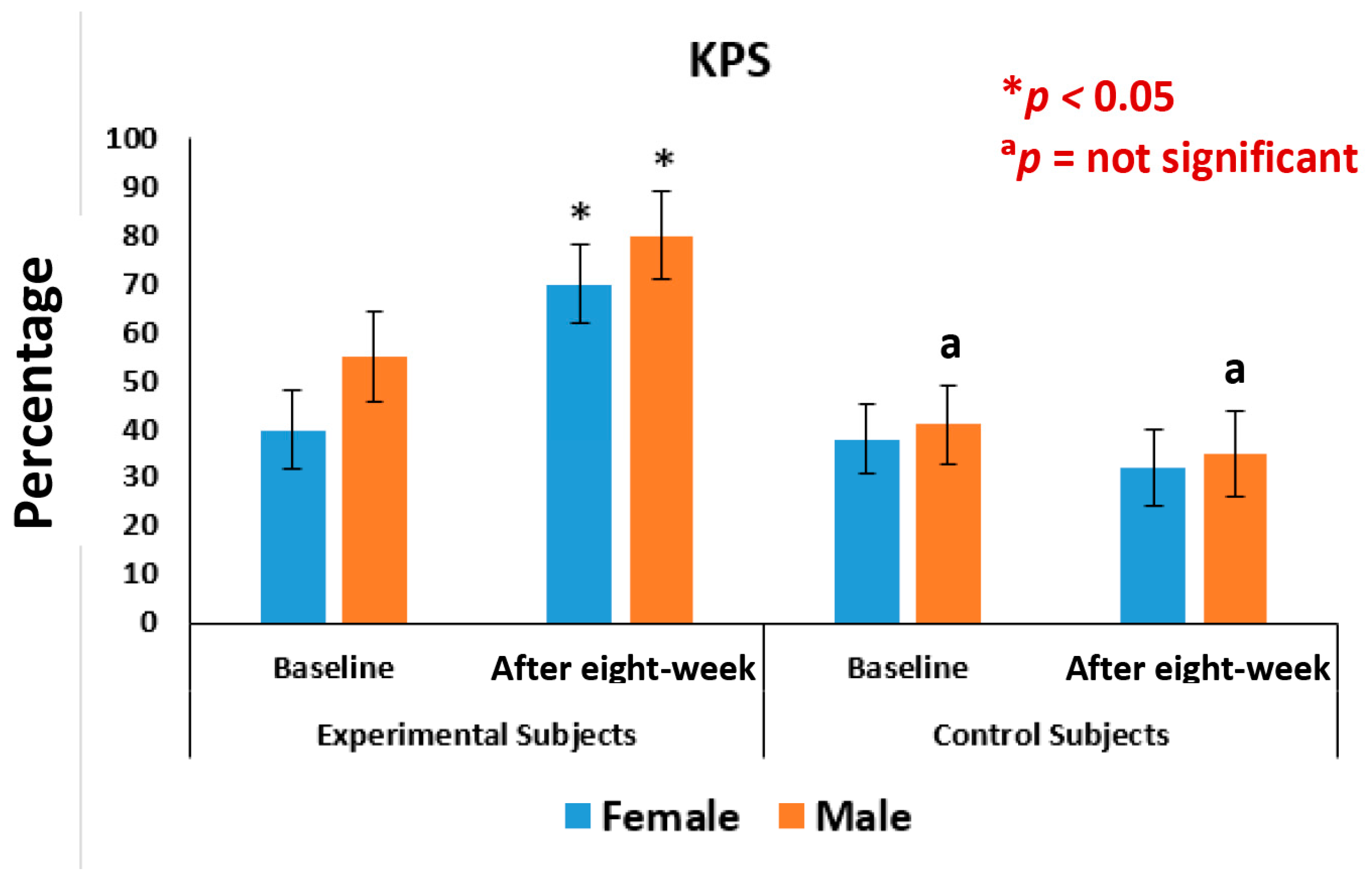

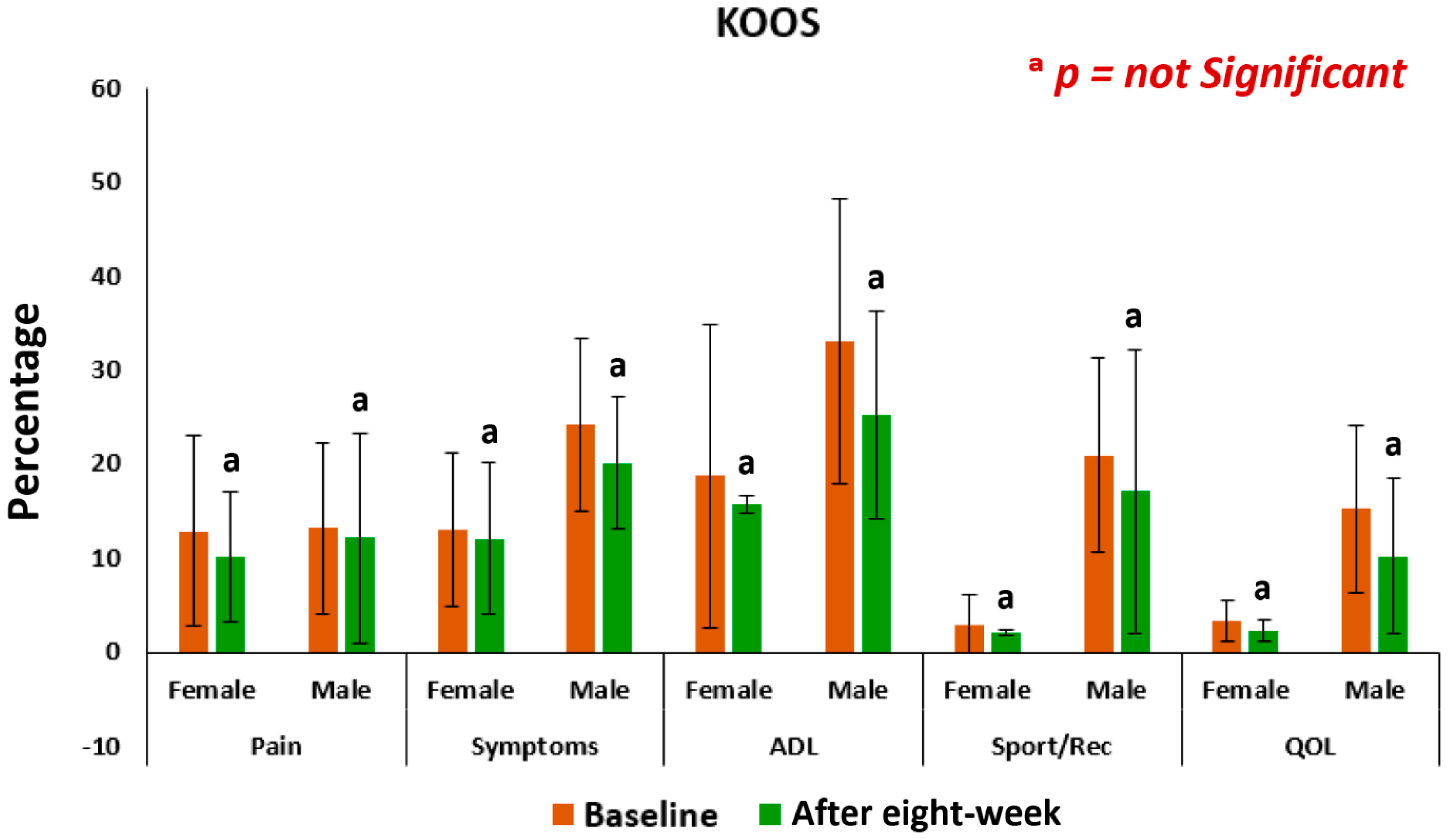

3.3. Pain, Stiffness, Performance Parameters

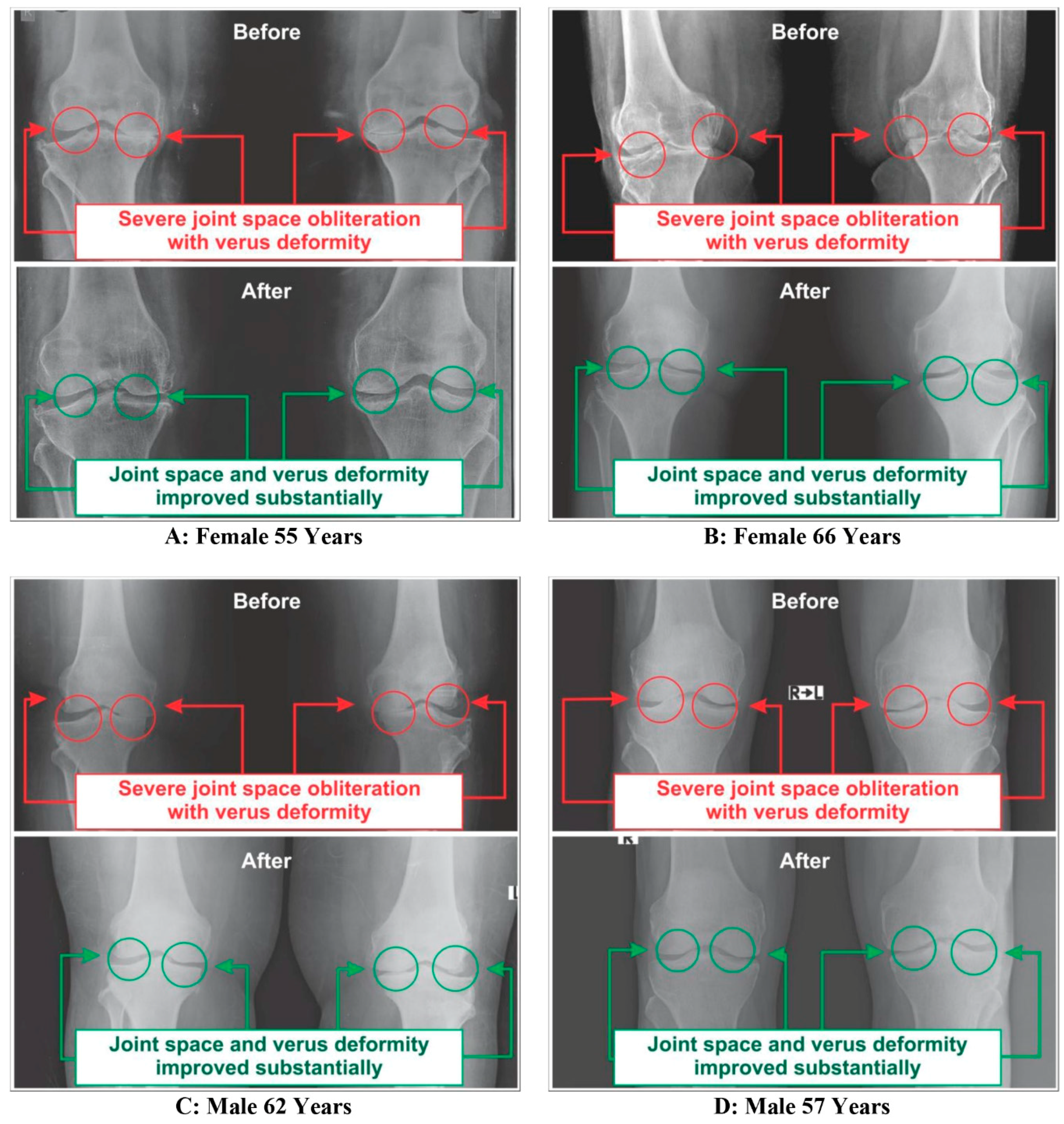

3.4. Improvements on Bone Health as per Radiological Images asAassessed by Kellgren-Lawrance Grading Scale

3.5. Safety and Cost Evaluation

4. Discussion

- The living substance of bone is composed of a hard-outer shell and a spongy matrix of inner tissues. To meet an individual’s metabolic needs, our body releases calcium from the bone into the bloodstream allowing the bone to grow or repair from injuries during the skeleton’s remodeling [61]. It is regulated by two stages such as osteoblasts (cells that build up) and osteoclasts (cells that break down). A healthy bone structure is maintained, when the bone-forming activity is greater than the breakdown of bone.

- Osteoblasts produce inactive osteocalcin and it needs vitamin-K2 to become fully activated and bind calcium to make the skeleton stronger and less susceptible to fracture [28]. Again, the matrix Gla protein (MGP) of vitamin-K2 is a central calcification inhibitor produced by the cells of vascular smooth muscles and regulates the potentially fatal accumulation of calcium which keeps calcium from accumulating in the walls of blood vessels [62].

- However, several researchers have suggested that increased consumption of calcium supplements helps strengthen the skeleton but, at the same time, can raise the risk for heart disease as they deposited in blood vessel walls and soft tissues [63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70]. On the contrary, increased vitamin-K2 intake could be a means of lowering calcium-associated health risks as it is associated with the inhibition of arterial calcification and arterial stiffening [71].

- Further, it may be possible to fight osteoporosis and simultaneously prevent the calcification and stiffening of the arteries by striking the right balance in intake of calcium and vitamin-K2, as in the modern manufacturing processes vitamin-K2 content in the food supply has significantly reduced [71,72].

- Therefore, the risks for blood-vessel calcification and heart problems are significantly lowered and the elasticity of the vessel wall is increased, if at least 32 µg of vitamin-K2 is present in the diet [73]. Hence, 100 µg of vitamin-K2 per day has been recommended in the supplement.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Felson, D.T. Epidemiology of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Epidemiol. Rev. 1988, 10, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bijlsma, J.W.; Berenbaum, F.; Lafeber, F.P. Osteoarthritis: An update with relevance for clinical practice. Lancet 2011, 377, 2115–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, V.L.; Hunter, D.J. The epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2014, 28, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, M.; Smith, E.; Hoy, D.; Nolte, S.; Ackerman, I.; Fransen, M.; Laslett, L.L. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: Estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Priority Diseases and Reason for Inclusion. 2013. Available online: http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/priority_medicines/Ch6_12Osteo.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2012).

- Garnero, P.; Piperno, M.; Gineyts, E.; Christgau, S.; Delmas, P.D. Cross sectional evaluation of biochemical markers of bone, cartilage, and synovial tissue metabolism in patients with knee osteoarthritis: Relations with disease activity and joint damage. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2001, 60, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, A. Diagnosis, Prevention & Phytotherapy for Osteoarthritic Disorders, 1st ed.; Omni Scriptum Publishing Group: Chisinau, Moldova, 2017; ISBN 978-3-330-65274-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly, A. Assessment of relationship between calcium-phosphorus ratio and parathyroid hormone levels in serum of osteoarthritic disordered patients: A diagnostic protocol. IOSR J. Dent. Med Sci. 2017, 16, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly, A. Determination of the impact of functional instability of parathyroid hormone and the calcium-phosphorus ratio as risk factors during osteoarthritic disorders using receiver operating characteristic curves. Int. Arch. BioMed. Clin. Res. 2017, 3, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bennell, K.L.; Hunter, D.J.; Hinman, R.S. Management of osteoarthritis of the knee. BMJ 2012, 345, e4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, R.S.; Kaplan, J.L. The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy, 19th ed.; Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp: Kenilworth, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, F.; Boyce, A. Diseases of Bone and Mineral Metabolism. Available online: https://www.endotext.org (accessed on 4 December 2012).

- Thomas, S.; Browne, H.; Mobasheri, A.; Rayman, M.P. What is the evidence for a role for diet and nutrition in osteoarthritis? Rheumatology 2018, 57, iv61–iv74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho Pereira, D.; Lima, R.P.A.; de Lima, R.T.; Gonçalves, M.D.C.R.; de Morais, L.C.S.L.; Franceschini, S.D.C.C.; de Carvalho Costa, M.J. Association between obesity and calcium: Phosphorus ratio in the habitual diets of adults in a city of North eastern Brazil: An epidemiological study. Nutr. J. 2013, 12, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zeng, C.; Wei, J.; Yang, T.; Gao, S.-G.; Li, Y.-S.; Luo, W.; Xiong, Y.L.; Lei, G.H. Serum calcium concentration is inversely associated with radiographic knee osteoarthritis Across-sectional study. Medicine 2016, 95, e2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Open Stax. Bone Tissue and the Skeletal System. In Anatomy and Physiology; OpenStax CNX: Houston, TX, USA, 2016; Chapter 6; Available online: http://cnx.org/contents/14fb4ad7-39a1-4eeeab6e3ef2482e3e22@8.24 (accessed on 26 February 2016).

- Endres, D.B.; Rude, R.K. Mineral and bone metabolism. In Tietz Textbook of Clinical Chemistry, 3rd ed.; Burtis, C.A., Ashwood, E.R., Eds.; W.B Saunders Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1999; pp. 1395–1457. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, L. Clinical Laboratory Diagnostics: Use and Assessment of Clinical Laboratory Results, 1st ed.; TH-Books Verlagsgesellschaft: Frankfurt, Germany, 1998; pp. 241–247. [Google Scholar]

- Walwadkar, S.D.; Suryakar, A.N.; Katkam, R.V.; Kumbar, K.M.; Ankush, R.D. Oxidative stress and calcium phosphorus levelsinrheumatoid arthritis. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2006, 21, 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemi, V.E.; Karkkainen, M.U.; Rita, H.J.; Laaksonen, M.M.; Outila, T.A.; Lamberg-Allardt, C.J. Low calcium: Phosphorus ratio in habitual diets affects serum parathyroid hormone concentration and calcium metabolism in healthy women with adequate calcium intake. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 103, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whybro, A.; Jagger, H.; Barker, M.; Eastell, R. Phosphate supplementation in young men: Lack of effect on calcium homeostasis and bone turnover. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 52, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deftos, L.J. Clinical Essentials of Calcium and Skeletal Metabolism, 1st ed.; Professional Communication Inc.: West Islip, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 1–208. [Google Scholar]

- Haussler, M.R.; Whitfield, G.K.; Haussler, C.A.; Hsieh, J.C.; Thompson, P.D.; Seiznick, S.H.; Dominguez, C.E.; Jurutka, P.W. The nuclear vitamin D receptor: Biological and molecular regulatory properties revealed. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1998, 13, 325–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holick, M.F. Photobiology and Noncalcemic Actions of Vitamin D. In Principles of Bone Biology, 2nd ed.; Bilezikian, J.P., Raisz, L.G., Rodan, G.A., Eds.; Academic Press: Millbrae, CA, USA, 2002; Chapter 33; pp. 587–602. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, A.C.; Manson, J.E.; Abrams, S.A.; Aloia, J.F.; Brannon, P.M.; Clinton, S.K.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.A.; Gallagher, J.C.; Gallo, R.L.; Jones, G.; et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from The Institute of Medicine: What clinicians need to know. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holick, M.F.; Binkley, N.C.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Gordon, C.M.; Hanley, D.A.; Heaney, R.P.; Murad, M.H.; Weaver, C.M. Endocrine Society. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 1911–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetterstrom, R.; Dam, H.C.P.; Doisy, E.A. The discovery of antihaemorrhagic vitamin and its impact on neonatal health. Acta Paediatr. 2006, 95, 642–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauschka, P.V. Osteocalcin: The vitamin K-dependent Ca2+-binding protein of bone matrix. Pathophysiol. Haemost. Thromb. 1986, 16, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, M.P. Hormesis defined. Ageing Res. Rev. 2008, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammon, H. Boswellic acids and their role in chronic inflammatory diseases. In Anti-Inflammatory Nutraceuticals and Chronic Diseases; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 291–327. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, E. Frankincense: Systematic review. BMJ 2008, 337, a2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.; Samarakoon, S.; Chandola, H.; Ravishankar, B. Clinical evaluation of Boswellia serrata (Shallaki) resin in the management of Sandhivata (osteoarthritis). Ayu 2011, 32, 478–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natarajan, S.; Majeed, M. To assess the efficacy & safety of NILIN™ SR tablets in the management of osteoarthritis of knee. Int. J. Pharm. Life Sci. 2012, 3, 1413–1423. [Google Scholar]

- Morr, C.V. Whey proteins: Manufacture. In Developments in Dairy Chemistry-4: Functional Milk Proteins; Fox, P.F., Ed.; Elsevier Applied Science: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 245–284. [Google Scholar]

- Sukkar, S.G.; Bounous, U.G. The role of whey protein in antioxidant defense. Riv. Ital. Nutr. Parenter. Enter. 2004, 22, 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Roos, E.M.; Lohmander, L.S. The Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS): From joint injury to osteoarthritis. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2003, 1, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schag, C.C.; Heinrich, R.L.; Ganz, P.A. Karnofsky performance status revisited: Reliability, validity, and guidelines. J. Clin. Oncol. 1984, 2, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaylova, V.; Ilkova, P. Photometric determination of micro amounts of calcium with arsenazo III. Anal. Chim. Acta 1971, 53, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, P.J. Affinity and stoichiometry of calcium binding by arsenazo III. Anal. Biochem. 1981, 110, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RaiszL, G.; Yajnik, C.H.; Bockman, R.S.; Bower, B. Comparison of commercially available parathyroid hormone immunoassay in the differential diagnosis of hypercalcemia due to primary hyperparathyroidism or malignancy. Ann. Intern. Med. 1979, 91, 739–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallette, L.E. The parathyroid poly hormones: New concepts in the spectrum of peptide hormone action. Endocr. Rev. 1991, 12, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, L.; Rosenblum, S.; Zaazra, J.; Wong, J. Intact PTH is stable in unfrozen EDTA plasma for 48 hours prior to laboratory analysis. Clin. Chem. 1995, 41, S47. [Google Scholar]

- Engvall, E.; Perlmann, P. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, Elisa: 3. Quantitation of specific antibodies by enzyme-labeled anti-immunoglobulin in antigen-coated tubes. J. Immunol. 1972, 109, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kellgren, J.H.; Lawrence, J.S. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1957, 16, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balazs, E.A. Viscosupplementation for treatment of osteoarthritis: From initialdiscovery to current status and results. Surg Technol. Int. 2004, 12, 278–289. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, W. Cell-based cartilage repair: Illusion or solution for osteoarthritis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2007, 19, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenwald, K.; Ertl, K.; Fletcher, K.E.; Whittle, J. Patterns of arthritis medication use in a community sample. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2012, 3, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, N.K.; Mishra, V.K.; Dubey, R.; Syed-Abdul, S.; Wang, J.R.; Deng, W.P. Combating Osteoarthritis through Stem Cell Therapies by Rejuvenating Cartilage: A Review. Stem Cells Int. 2018, 2018, 5421019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.Y. Vitamin D in the prevention and treatment of osteoarthritis: From clinical interventions to cellular evidence. Nutrients 2019, 11, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlebowski, R.T.; Pettinger, M.; Johnson, K.C.; Wallace, R.; Womack, C.; Mossavar-Rahmani, Y.; Eaton, C. Calcium plus vitamin supplementation and joint symptoms in postmenopausal women in the women’s health initiative randomized trial. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 1302–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xiao, W.; Luo, W.; Zeng, C.; Deng, Z.; Ren, W.; Lei, G. Alteration of amino acid metabolism in osteoarthritis: Its implications for nutrition and health. Amino Acids 2016, 48, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Camara, C.C.; Dowless, G.V. Glucosamine sulphate for osteoarthritis. Ann. Pharmacother. 1998, 32, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fransen, M.; Agaliotis, M.; Nairn, L.; Votrubec, M.; Bridgett, L.; Su, S.; Woodward, M. Glucosamine and chondroitin for knee osteoarthritis: A double-bind randomised placebo-controlled clinical trial evaluating single and combination regimens. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015, 74, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konopka, A.R.; Nair, K.S. Mitochondrial and skeletal muscle health with advancing age. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2013, 379, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, K.; Engelhardt, M. Strength and muscle mass loss with aging process. Age and strength loss. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2014, 3, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brotto, M.; Abreu, E.L. Sarcopenia: Pharmacology of today and tomorrow. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2012, 343, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Blizzard, L.; Fell, J.; Giles, G.; Jones, G. Association between dietary nutrient intake and muscle and strength in community-dwelling older adults: The Tasmanian Older Adult Cohort Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2010, 58, 2129–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Landi, F. Sarcopenia. Clin. Med. 2014, 14, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, I.H. Sarcopenia: Origins and clinical relevance. J. Nutr. 1997, 127, 990S–991S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, W.J. Skeletal muscle loss: Cachexia, sarcopenia, and inactivity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1123S–1127S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, R.P.; Weaver, C.M. Newer perspectives on calcium nutrition and bone quality. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2005, 24, 574S–581S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theuwissen, E.; Smit, E.; Vermeer, C. The role of vitamin K in soft-tissue calcification. Adv. Nutr. 2012, 3, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolland, M.J.; Avenell, A.; Baron, J.A.; Grey, A.; MacLennan, G.S.; Gamble, G.D.; Reid, I.R. Effect of calcium supplements on risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular events: Meta-analysis. BMJ 2010, 341, c3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolland, M.J.; Grey, A.; Avenell, A.; Gamble, G.D.; Reid, I.R. Calcium supplements with or without vitamin D and risk of cardiovascular events: Reanalysis of the Women’s Health Initiative limited access dataset and meta-analysis. BMJ 2011, 342, d2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Kaaks, R.; Linseisen, J.; Rohrmann, S. Associations of dietary calcium intake and calcium supplementation with myocardial infarction and stroke risk and overall cardiovascular mortality in the Heidelberg cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition study (EPIC-Heidelberg). Heart 2012, 98, 920–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaëlsson, K.; Melhus, H.; Warensjö Lemming, E.; Wolk, A.; Byberg, L. Long term calcium intake and rates of all cause and cardiovascular mortality: Community based prospective longitudinal cohort study. BMJ 2013, 346, f228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentti, K.; Tuppurainen, M.T.; Honkanen, R.; Sandini, L.; Kroger, H.; Alhava, E.; Saarikoski, S. Use of calcium supplements and the risk of coronary heart disease in 52–62-year-old women: The Kuopio Osteoporosis Risk Factor and Prevention Study. Maturitas 2009, 63, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Murphy, R.A.; Houston, D.K.; Harris, T.B.; Chow, W.H.; Park, Y. Dietary and supplemental calcium intake and cardiovascular disease mortality: The National Institutes of Health-AARP diet and health study. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beulens, J.W.; Bots, M.L.; Atsma, F.; Bartelink, M.L.E.; Prokop, M.; Geleijnse, J.M.; Van Der Schouw, Y.T. High dietary menaquinone intake is associated with reduced coronary calcification. Atherosclerosis 2009, 203, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geleijnse, J.M.; Vermeer, C.; Grobbee, D.E.; Schurgers, L.J.; Knapen, M.H.; van der Meer, I.M.; Hofman, A.; Witteman, J.C. Dietary intake of menaquinone is associated with a reduced risk of coronary heart disease: The Rotterdam Study. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 3100–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theuwissen, E.; Magdeleyns, E.J.; Braam, L.A.J.L.M.; Teunissen, K.J.; Knapen, M.H.; Binnekamp, I.A.G.; Vermeer, C. Vitamin K status in healthy volunteers. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corson, T.W.; Crews, C.M. Molecular understanding and modern application of traditional medicines: Triumphs and trials. Cell 2007, 130, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S. From exotic spice to modern drug? Cell 2007, 130, 765–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belcaro, G.; Dugall, M.; Luzzi, R.; Hosoi, M.; Ledda, A.; Feragalli, B.; Giacomelli, L. Phytoproflex®: Supplementary management of osteoarthrosis: A supplement registry. Minerva Med. 2018, 109, 88–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatcher, H.; Planalp, R.; Cho, J.; Torti, F.M.; Torti, S.V. Curcumin: From ancient medicine to current clinical trials. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008, 65, 1631–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcaro, G.; Cesarone, M.R.; Dugall, M. Product-evaluation registry of Meriva®, a curcumin-phosphatidylcholine complex, for the complementary management of osteoarthritis. Panminerva Med. 2010, 52, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Resch, K.L.; Hill, S.; Ernst, E. Use of complimentary therapies by individuals with ‘arthritis’. Clin. Rheumatol. 1997, 16, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayliss, M.T. Biochemical changes in shumanosteoarthrotic cartilage. In Studies in Osteoarthrosis Pathogenesis, Intervention, Assessment; Lott, D.J., Jasani, M.K., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1987; pp. 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Cuaz-Pérolin, C.; Billiet, L.; Baugé, E.; Copin, C.; Scott-Algara, D.; Genze, F.; Rouis, M. Anti -inflammatory and antiatherogenic effects of the NF-κB inhibitor acetyl-11-keto-β-boswellic acid in LPS-challenged ApoE−/− mice. Arteriosclerosis. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008, 28, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrovets, T.; Büchele, B.; Krauss, C.; Laumonnier, Y.; Simmet, T. Acetyl-boswellic acids inhibit lipopolysaccharide-mediated TNF-α induction in monocytes by direct interaction with IκB kinases. J. Immunol. 2005, 174, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchele, B.; Zugmaier, W.; Simmet, T. Analysis of pentacyclic triterpenic acids from frankincense gum resins and related phytopharmaceuticals by high-performance liquid chromatography. Identification of lupeolic acid, a novel pentacyclic triterpene. J. Chromatogr. B 2003, 791, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, M.; Majeed, S.; Narayanan, N.K.; Nagabhushanam, K. A pilot, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to assess the safety and efficacy of a novel Boswellia serrata extract in the management of osteoarthritis of the knee. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 1457–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearle, A.D.; Scanzello, C.R.; George, S.; Mandl, L.A.; DiCarlo, E.F.; Peterson, M.; Crow, M.K. Elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels are associated with local inflammatory findings in patients with osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2007, 15, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Wang, O. Clinical trials in “emerging markets”: Regulatory considerations and other factors. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2013, 36, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, R.R. Protein supplements and exercises. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 72, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut Solak, B.; Akin, N. Functionality of Whey Protein. Int. J. Health Nutr. 2012, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Belcaro, G.; Nicolaides, A.N. A new role for natural drugs in cardiovascular medicine. Angiology 2001, 52, S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.W.; Housh, T.J.; Johnson, G.O.; Schmidt, R.J.; Housh, D.J.; Coburn, J.W.; Malek, M.H.; Mielke, M. Effects of a protease supplement on eccentric exercise-induced markers of delayed-onset muscle soreness and muscle damage. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2007, 21, 661–667. [Google Scholar]

- Cockburn, E.; Hayes, P.R.; French, D.N.; Stevenson, E.; St Clair Gibson, A. Acute milk-based protein-CHO supplementation attenuates exercise-induced muscle damage. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2008, 33, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Control Group | Experimental Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Female | Male | |

| No of subjects (%) | 27 (60.00) | 18 (40.00) | 39 (61.90) | 24 (38.10) |

| Mean age (SD) in years | 60.89 (11.37) | 61.38 (10.21) | 60.78 (11.13) | 61.12 (13.68) |

| Mean weight (SD) in kg | 71.71 (5.05) | 71.32 (5.11) | 71.67 (6.12) | 70.77 (6.78) |

| Mean height (SD) in meter | 1.55 (0.92) | 1.58 (0.88) | 1.56 (0.93) | 1.57(0.98) |

| Mean BMI (SD) in kg/m² | 29.85 (6.94) | 28.57 (6.64) | 29.43 (7.11) | 28.71 (6.32) |

| Mean symptom duration in years (SD) | 6.89 (1.90) | 7.78(1.78) | 6.12 (2.11) | 7.26 (2.01) |

| Indian ethnic group (%) | ||||

| Bengali | 8 (29.63) | 5 (27.78) | 14 (35.90) | 6 (25.00) |

| Gujrati | 3 (11.11) | 2 (11.11) | 6 (15.38) | 3 (12.50) |

| Marwaree | 5 (18.52) | 2 (11.11) | 4 (10.26) | 4 (16.67) |

| Marathi | 3 (11.11) | 2 (11.11) | 3 (7.69) | 3 (12.50) |

| Tamil | 2 (7.41) | 2 (11.11) | 2 (5.13) | 2 (8.33) |

| Punjabi | 2 (7.41) | 1 (5.56) | 4 (10.26) | 2 (8.33) |

| Shindhi | 1 (3.70) | 2 (11.11) | 3 (7.69) | 2 (8.33) |

| North East India | 3 (11.11) | 2 (11.11) | 3 (7.69) | 2 (8.33) |

| Dietary habits (%) | ||||

| Vegetarian | 12 (44.44) | 10 (55.56) | 28 (71.79) | 10 (41.67) |

| Non-vegetarian | 15 (55.56) | 8 (44.44) | 11 (28.21) | 14 (58.33) |

| Other habits (%) | ||||

| Smoking | 3 (11.11) | 9 (50.00) | 2 (5.13) | 5 (20.83) |

| Drinking alcohol | 7 (25.93) | 11 (61.11) | 6 (15.38) | 11 (45.83) |

| Drinking tea and coffee | 12 (44.44) | 16 (88.89) | 18 (46.15) | 12 (50.00) |

| Chewing tobacco | 2 (7.41) | 4 (22.22) | 3 (7.69) | 4 (16.67) |

| Analysis of radiological reports (%) | ||||

| KOA in right knee with osteophytes | 10 (37.04) | 8 (44.44) | 12 (30.77) | 7 (29.17) |

| KOA in left knee with osteophytes | 17 (62.96) | 10 (55.56) | 27 (69.23) | 17 (70.83) |

| Work status (%) | ||||

| Employed fulltime | 2 (7.41) | 7 (38.89) | 3 (7.69) | 8 (33.33) |

| Employed part time | 1 (3.70) | 2 (11.11) | 2 (5.13) | 2 (8.33) |

| Housewife / Home- maker | 20 (74.07) | 0 (0.00) | 27 (69.23) | 0 (0.00) |

| Retired | 2 (7.41) | 6 (33.33) | 4 (10.26) | 10 (41.67) |

| Self employed | 2 (7.41) | 3 (16.67) | 3 (7.69) | 4 (16.67) |

| Marital status (%) | ||||

| Single | 2 (7.41) | 1 (5.56) | 2 (5.13) | 1 (4.17) |

| Married | 17 (62.96) | 14 (77.78) | 28 (71.79) | 20 (83.33) |

| Separated | 2 (7.41) | 1 (5.56) | 2 (5.13) | 1 (4.17) |

| Divorced | 1 (3.70) | 2 (11.11) | 2 (5.13) | 2 (8.33) |

| Widowed | 5 (18.52) | 0 (0.00) | 5 (12.82) | 0 (0.00) |

| Multiple complaints or comorbidities (%) | ||||

| Constipation | 17 (62.96) | 10 (55.56) | 27 (69.23) | 16 (66.67) |

| Acidity and reflux | 12 (44.44) | 7 (38.89) | 16 (41.03) | 18 (75.00) |

| Insomnia | 10 (37.04) | 8 (44.44) | 18 (46.15) | 8 (33.33) |

| Varicose veins | 8 (29.63) | 6 (33.33) | 14 (35.90) | 11 (45.83) |

| Urinary incontinence | 13 (48.15) | 7 (38.89) | 19 (48.72) | 18 (75.00) |

| Crepitus during knee flexion | 14 (51.85) | 8 (44.44) | 21 (53.85) | 19 (79.17) |

| Morning stiffness (<30 min.) | 17 (62.96) | 10 (55.56) | 18 (46.15) | 14 (58.33) |

| Measures taken to diminish pain and inflammation (%) | ||||

| Kneecap uses | 24 (88.89) | 16 (88.89) | 34 (87.18) | 18 (75.00) |

| Lumbar belt uses | 5 (18.52) | 2 (11.11) | 4 (10.26) | 2 (8.33) |

| Paracetamol and NSAID use | 26 (96.30) | 16 (88.89) | 37 (94.87) | 21 (87.50) |

| Arthrocentesis (four months ago) | 11 (40.74) | 7 (38.89) | 8 (20.51) | 5 (20.83) |

| Use of hyaluronic acid injection | 8 (29.63) | 7 (38.89) | 6 (15.38) | 5 (20.83) |

| Use of corticosteroid injection | 6 (22.22) | 8 (44.44) | 7 (17.95) | 6 (25.00) |

| Massage with herbal or other gels | 18 (66.67) | 20 (111.11) | 25 (64.10) | 17 (70.83) |

| Homeopathic treatment | 19 (70.37) | 16 (88.89) | 19 (48.72) | 18 (75.00) |

| Ayurvedic treatment | 21 (77.78) | 17 (94.44) | 20 (51.28) | 20 (83.33) |

| Stick/walker use | 18 (66.67) | 11 (61.11) | 18 (46.15) | 10 (41.67) |

| Supplements taken to reduce pain or improve fitness (%) | ||||

| Calcium with vitamin D | 11 (40.74) | 10 (55.56) | 32 (82.05) | 19 (79.17) |

| Vitamin D injection | 8 (29.63) | 7 (38.89) | 14 (35.90) | 6 (25.00) |

| Glucosamine | 6 (22.22) | 8 (44.44) | 9 (23.08) | 4 (16.67) |

| Glucosamine and chondroitin | 5 (18.52) | 4 (22.22) | 7 (17.95) | 3 (12.50) |

| Comparison of Two Biomarkers | Female (n = 39) | Male (n = 24) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r-Value | p-Value | r-Value | p-Value | |

| CPRb-Vs-CPRt | −0.175 | 0.286 | −0.201 | 0.346 |

| PTHb-Vs-PTHt | 0.496 | 0.001 | 0.664 | 0.0004 |

| Vit.Db-Vs-Vit.Dt | 0.786 | 0.000 | 0.390 | 0.000 |

| Biomarker | Control Group without Supplement (n = 45) | Experimental Group with Supplement (n = 63) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | After Eight-Week | Baseline | After Eight-Week | |||||

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | |

| CPR (%) | 26.73 | 17.6 | 20.58 | 19.31 | 6.91 | 6.5 | 9.75 | 7.41 |

| PTH (%) | 41.67 | 60.72 | 41.49 | 58.31 | 41.6 | 40.83 | 20.53 | 18.36 |

| Vitamin D (%) | 43.13 | 49.37 | 43.45 | 49.67 | 43.6 | 30.89 | 33.12 | 29.35 |

| Knee Joints | Gradation | Control Group (n = 45) | Experimental Group (n = 63) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | After Eight-Week | Baseline | After Eight-Week | ||||||

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | ||

| KOA (Rt. knee) | Grade-0 | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Grade-1 | None | None | None | None | None | None | 4 | 6.35 | |

| Grade-2 | None | None | None | None | None | None | 8 | 12.70 | |

| Grade-3 | 23 | 51.11 | 21 | 46.67 | 28 | 44.44 | 30 | 47.62 | |

| Grade-4 | 22 | 48.89 | 24 | 53.33 | 35 | 55.56 | 21 | 33.33 | |

| KOA (Lt. knee) | Grade-0 | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Grade-1 | None | None | None | None | None | None | 3 | 4.76 | |

| Grade-2 | None | None | None | None | None | None | 7 | 11.11 | |

| Grade-3 | 19 | 42.22 | 17 | 37.78 | 27 | 42.86 | 31 | 49.21 | |

| Grade-4 | 26 | 57.78 | 28 | 62.22 | 36 | 57.14 | 22 | 34.92 | |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ganguly, A. Role of Jumpstart Nutrition®, a Dietary Supplement, to Ameliorate Calcium-to-Phosphorus Ratio and Parathyroid Hormone of Patients with Osteoarthritis. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci7120105

Ganguly A. Role of Jumpstart Nutrition®, a Dietary Supplement, to Ameliorate Calcium-to-Phosphorus Ratio and Parathyroid Hormone of Patients with Osteoarthritis. Medical Sciences. 2019; 7(12):105. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci7120105

Chicago/Turabian StyleGanguly, Apurba. 2019. "Role of Jumpstart Nutrition®, a Dietary Supplement, to Ameliorate Calcium-to-Phosphorus Ratio and Parathyroid Hormone of Patients with Osteoarthritis" Medical Sciences 7, no. 12: 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci7120105

APA StyleGanguly, A. (2019). Role of Jumpstart Nutrition®, a Dietary Supplement, to Ameliorate Calcium-to-Phosphorus Ratio and Parathyroid Hormone of Patients with Osteoarthritis. Medical Sciences, 7(12), 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci7120105