Determinants of Entero-Invasive and Non-Entero-Invasive Diarrheagenic Bacteria Among HIV-Positive and HIV-Negative Adults in Ghana

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Laboratory Diagnostics

2.3. Statistics

2.4. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

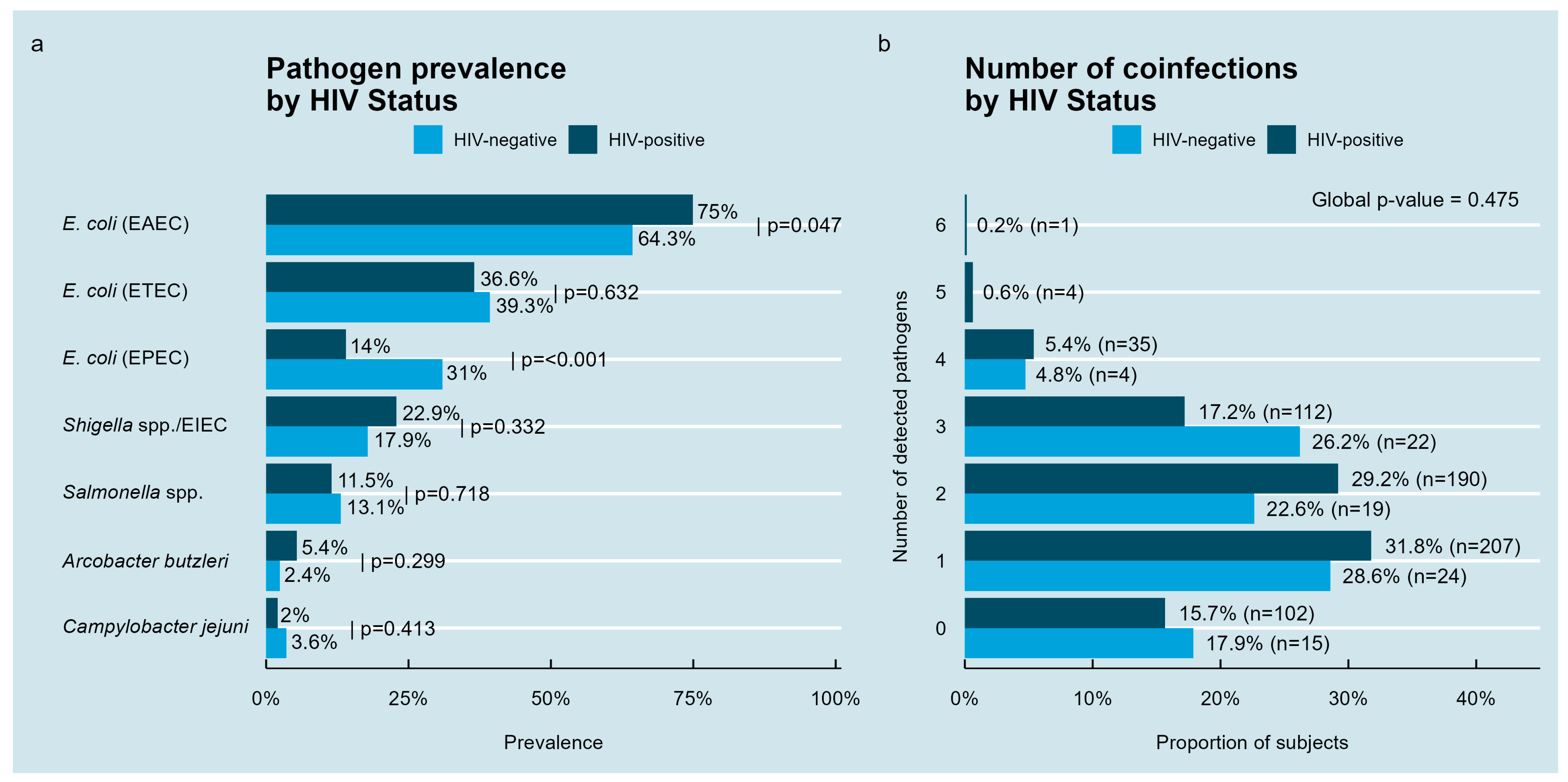

3.2. Detection of Bacterial Enteropathogens in Stool Samples According to HIV Infection

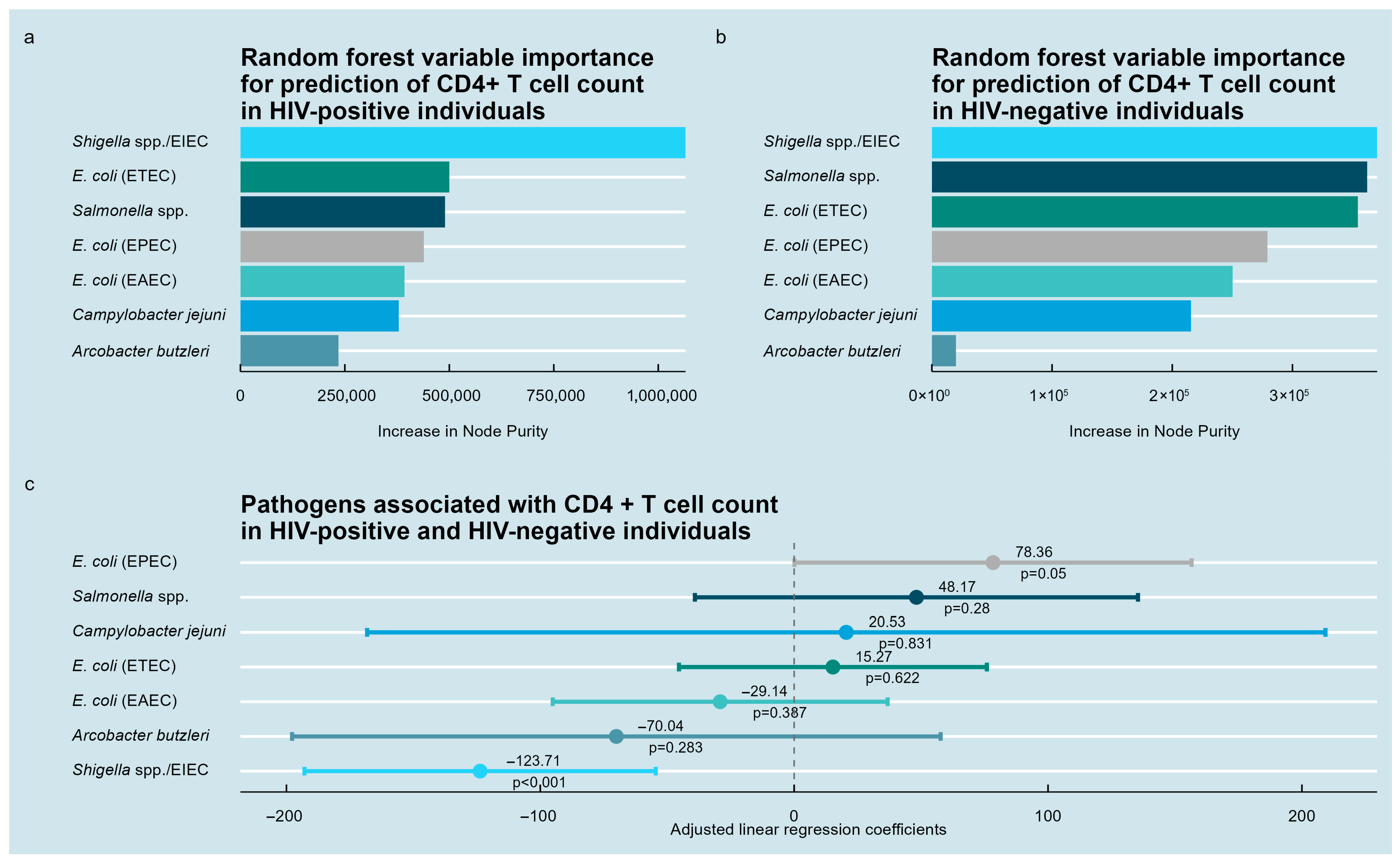

3.3. Enteric Pathogens Associated with CD4+ T-Lymphocyte Counts

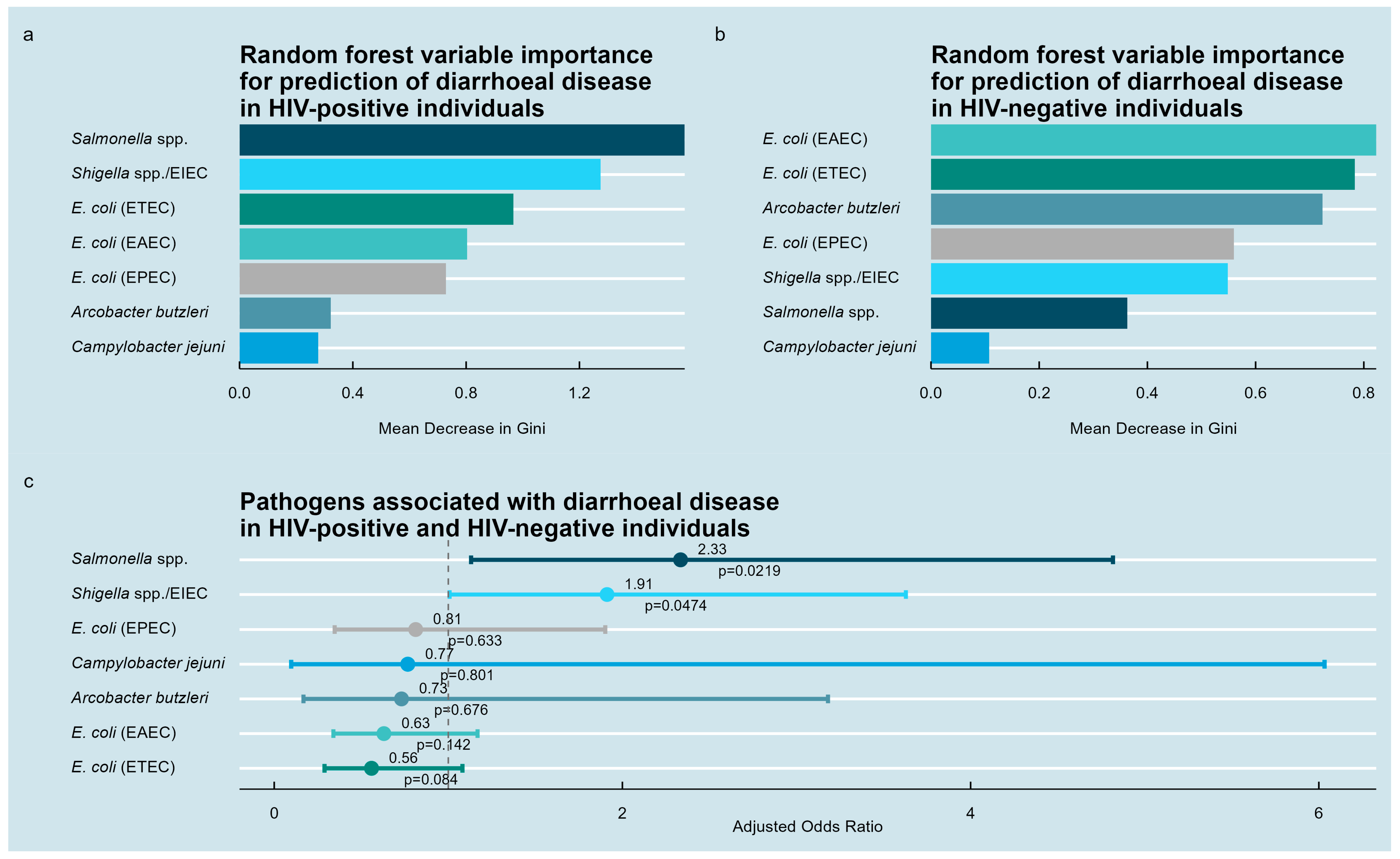

3.4. Pathogens Associated with Diarrheal Disease

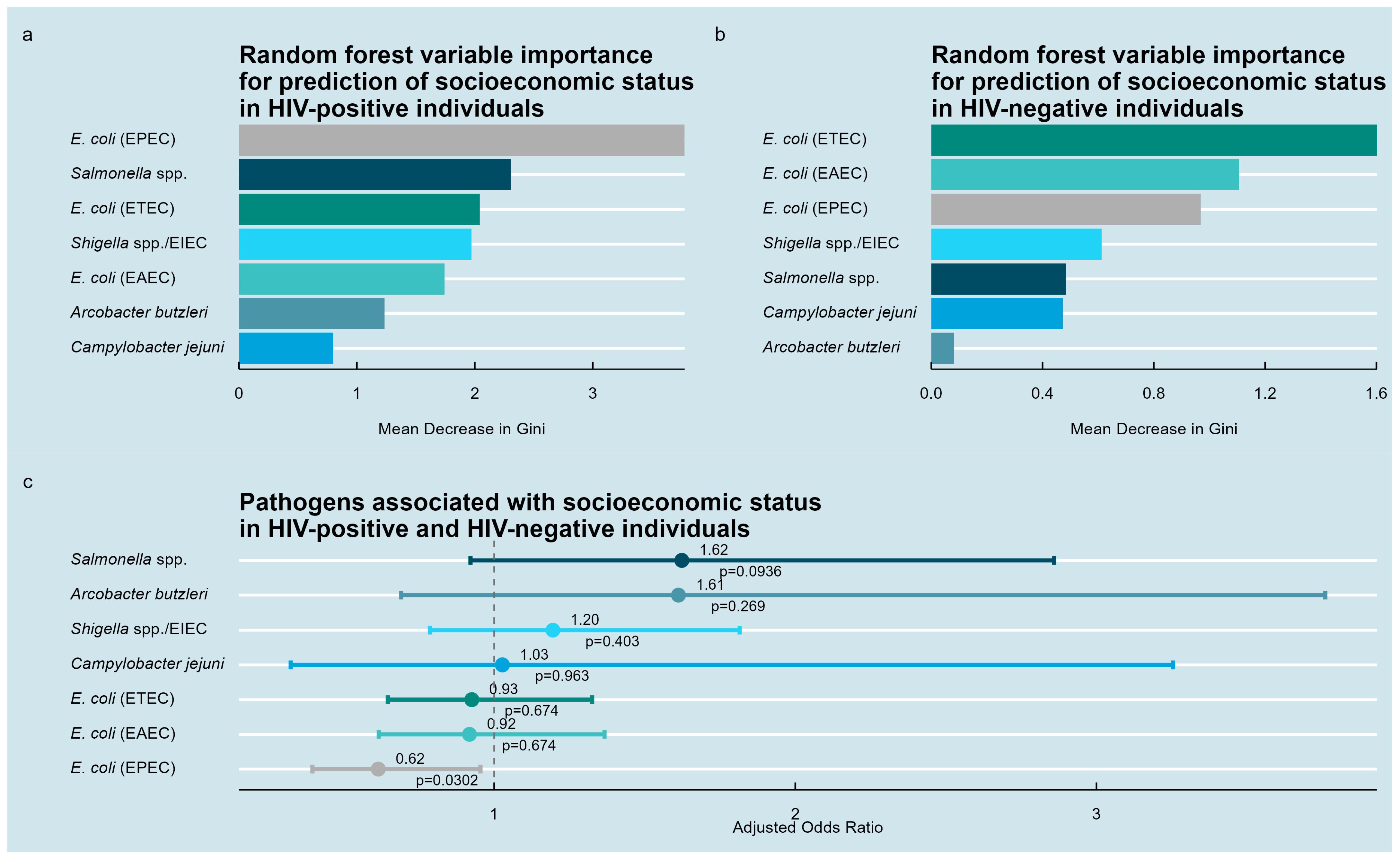

3.5. Pathogens Associated with the Socioeconomic Status Index

3.6. Correlations of Cycle Threshold (Ct) Values with CD4+ T-Lymphocyte Count

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 95% CI | 95% confidence interval |

| AIDS | acquired immunodeficiency syndrome |

| cART | combination antiretroviral therapy |

| Ct | cycle threshold |

| DNA | desoxyribonucleic acid |

| EAEC | enteroaggregative Escherichia coli |

| EIEC | enteroinvasive Escherichia coli |

| EPEC | enteropathogenic Escherichia coli |

| ETEC | enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli |

| HIV | human immunodeficiency virus |

| IQR | inter-quartile range |

| min. | minute |

| µL | microliter |

| N | number |

| NA | not applicable |

| PCA | principal component analysis |

| PCR | polymerase chain reaction |

| PLWH | people-living-with-HIV |

| SD | standard deviation |

| sec. | second |

| SES | socio-economic status |

| spp. | species (plural) |

Appendix A

| PCR target | Salmonella spp. |

| Target gene | ttrC |

| Detection limit | 3.6 × 102 copies/µL |

| Forward primer | 5′-ATT-GTT-GAT-TCA-GGT-ACA-AAC-3′ |

| Reverse primer | 5′-AAT-TAG-CCA-TGT-TGT-AAT-CTC-3′ |

| Probe and modifications | 5′-JOE-CAA-GTT-CAA-CGC-GCA-ATT-TA-BHQ1-3′ |

| Positive control plasmid insert | 5′-CTG-GAC-ATT-GTT-GAT-TCA-GGT-ACA-AAC-CGT-CCC-CAA-GTT-CAA-CGC-GCA-ATT-TAA-CCC-TTA-CTC-GTT-ACC-AGG-CGG-AAC-GGA-TGG-CTG-GCT-GGC-TAT-TCT-CGG-CAC-CTT-CGG-CCT-GTG-GAT-AGC-GCT-ACT-GAT-TAT-TAT-TCG-TGA-AAC-GCT-GAA-CGG-ACT-CAC-CAG-GAG-ATT-ACA-ACA-TGG-CTA-ATT-TAA-CCC-3′ |

| GenBank accession number used for the insert | CP007365.2 |

| Reference | [55] |

| PCR target | Shigella spp./entero-invasive Escherichia coli (EIEC) |

| Target gene | ipaH |

| Detection limit | 3.6 × 102 copies/µL |

| Forward primer | 5′-CAG-AAG-AGC-AGA-AGT-ATG-AG-3′ |

| Reverse primer | 5′-CAG-TAC-CTC-GTC-AGT-CAG-3′ |

| Probe and modifications | 5′-ROX-ACA-GGT-GAT-GCG-TGA-GAC-TG-BHQ2-3′ |

| Positive control plasmid insert | 5′-CGC-AGG-CAG-AAG-AGC-AGA-AGT-ATG-AGA-TGC-TGG-AGA-ATG-AGT-ACT-CTC-AGA-GGG-TGG-CTG-ACC-GGC-TGA-AAG-CAT-CAG-GTC-TGA-GCG-GTG-ATG-CGG-ATG-CGC-AGA-GGG-AAG-CCG-GTG-CAC-AGG-TGA-TGC-GTG-AGA-CTG-AAC-AGC-AGA-TTT-ACC-GTC-AGC-TGA-CTG-ACG-AGG-TAC-TGG-CCC-TG-3′ |

| GenBank accession number used for the insert | M32063.1 |

| Reference | [55] |

| PCR target | Campylobacter jejuni |

| Target gene | gyrA |

| Detection limit | 3.6 × 102 copies/µL |

| Forward primer | 5′-CTA-TAA-CAA-CTG-CAC-CTA-CTA-AT-3′ |

| Reverse primer | 5′-ATG-AAA-TTT-TTG-CCA-GTG-GTG-3′ |

| Probe and modifications | 5′-FAM-CTT-AAT-AGC-CGT-CAC-CCC-AC-BHQ1-3′ |

| Positive control plasmid insert | 5′-CAT-TTT-CTA-TAA-CAA-CTG-CAC-CTA-CTA-ATT-CGT-CAT-TTT-TCT-CTT-TAA-ACT-TAA-TAG-CCG-TCA-CCC-CAC-GAC-TTA-CAC-GAC-CGA-TTT-CAC-GTA-CTT-TAG-CAA-GTG-GGA-ATT-TGA-TAC-ACA-TAC-CTT-TTT-TGG-TTA-CTG-CAA-AGA-GCA-TTT-TAC-CTT-GTG-TGC-TTA-CAC-TTT-CTT-CAT-TTT-CAA-GAT-TTT-CAT-CAT-CTA-AAT-TTT-CAA-TTT-CTT-GAT-TTT-CTA-AAT-TTT-CTT-CAC-CAC-CAC-TGG-CAA-AAA-TTT-CAT-CTT-CAT-3′ |

| GenBank accession number used for the insert | CP012244.1 |

| Reference | [55] |

| PCR target | Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) PCR 1 |

| Target gene | eae gene |

| Detection limit | 2.5 × 101 copies/µL |

| Forward primer | 5′-CAT-TGA-TCA-GGA-TTT-TTC-TGG-TGA-TA-3′ |

| Reverse primer | 5′-CTC-ATG-CGG-AAA-TAG-CCG-TTA-3′ |

| Probe and modifications | 5′-ROX-ATA-GTC-TCG-CCA-GTA-TTC-GCC-ACC-AAT-ACC-BHQ2-3′ |

| Positive control plasmid insert | 5′-CGT-CTT-CAT-TGA-TCA-GGA-TTT-TTC-TGG-TGA-TAA-TAC-CCG-TTT-AGG-TAT-TGG-TGG-CGA-ATA-CTG-GCG-AGA-CTA-TTT-CAA-AAG-TAG-TGT-TAA-CGG-CTA-TTT-CCG-CAT-GAG-CGG-CTG-3′ |

| GenBank accession number used for the insert | Z11541.1 |

| Reference | [54] |

| PCR target | Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) PCR 2 |

| Target gene | EAF plasmid sequence |

| Detection limit | 3.1 × 101 copies/µL |

| Forward primer | 5′-CAG-GGT-AAA-AGA-AAG-ATG-ATA-A-3′ |

| Reverse primer | 5′-GCA-TGG-AAC-ATC-GAT-CAG-TGA-3′ |

| Probe and modifications | 5′-6-FAM-TGG-AGT-GAT-CGA-ACG-GGA-TCC-A-BHQ1-3′ |

| Positive control plasmid insert | 5′-AAA-AAA-CAG-GGT-AAA-AGA-AAG-ATG-ATA-AGT-TAA-CGC-TTG-GAG-TGA-TCG-AAC-GGG-ATC-CAA-ATC-ACT-GAT-CGA-TGT-TCC-ATG-CGA-ATA-AGT-GAT-CGA-TCA-TGT-CGG-AAT-ATC-CAA-AAA-CCC-GAA-ATC-ACC-AGT-TGC-CAC-ATT-GAA-CGG-CGC-TGG-TGA-TTT-CGG-GTT-CGT-CAC-TTT-ATG-GAT-ACC-ATC-AAC-CCA-TTC-CCC-GGA-GAA-AGT-ATG-GGC-TGG-CTA-AAG-TGT-AGC-GNC-ATT-AAG-AGC-AGT-TAT-TTA-GTA-TTT-TAA-TGA-GTA-TCG-AAT-CTT-TAT-ATT-TGC-ATC-ATT-CCG-TTG-TTG-GTC-CGC-CTT-CTG-ACA-AGC-TGT-GTT-GGC-AGA-AGA-AAC-GTC-GTT-AGC-GGT-TCC-TAT-TTT-GTT-ACT-ACC-TAG-ATA-TAT-ATC-AGG-TTT-TTG-ATA-ATA-CAT-GGT-CCC-CAT-ATT-CAT-A-3′ |

| GenBank accession number used for the insert | X76137.1 |

| Reference | [54] |

| PCR target | Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) |

| Target gene | eltB gene (component 1) and estB gene (component 2) |

| Detection limit | 2.7 × 101 copies/µL |

| Component | 1 |

| Forward primer | 5′-GCG-TTA-CTA-TCC-TCT-CTA-TG-3′ |

| Reverse primer | 5′-TGA-TAT-TCC-GAA-CAT-AGT-TCT-GTA-3′ |

| Probe and modifications | 5′-JOE-TAG-ACT-GGG-GAG-CTC-CGT-GTG-C-BHQ1-3′ |

| Positive control plasmid insert | 5′-TAT-TTA-CGG-CGT-TAC-TAT-CCT-CTC-TAT-GTG-CAC-ACG-GAG-CTC-CCC-AGT-CTA-TTA-CAG-AAC-TAT-GTT-CGG-AAT-ATC-ACA-ACA-CAC-AAA-TAT-ATA-CGA-TAA-ATG-ACA-AGA-TAC-TAT-CAT-ATA-CGG-AAT-CGA-TGG-CAG-GCA-AAA-GAG-AAA-TGG-TTA-TCA-TTA-CAT-TTA-AGA-GCG-GCG-CAA-CAT-TTC-AGG-TCG-AAG-TCC-CGG-GCA-GTC-AAC-ATA-TAG-ACT-CCC-AAA-AAA-AAG-CCA-TTG-AAA-GGA-TGA-AGG-ACA-CAT-TAA-GAA-TCA-CAT-ATC-TGA-CCG-AGA-CCA-AAA-TTG-ATA-AAT-TAT-GTG-TAT-GGA-ATA-ATA-AAA-CCC-CCA-ATT-CAA-TT-3′ |

| GenBank accession number used for the insert | KJ716874.1 |

| Component | 2 |

| Forward primer | 5′-TCC-CTC-AGG-ATG-CTA-AAC-3′ |

| Reverse primer | 5′-CAA-CAA-AGC-AAC-AGG-TAC-ATA-CGT-3′ |

| Probe and modifications | 5′-JOE-ATA-GCA-CCC-GGT-ACA-AGC-AGG-BHQ1-3′ |

| Positive control plasmid insert | 5′-CAC-CTT-TCC-CTC-AGG-ATG-CTA-AAC-CAG-TAG-AGT-CTT-CAA-AAG-AAA-AAA-TCA-CAC-TAG-AAT-CAA-AAA-AAT-GTA-ACA-TTG-CAA-AAA-AAA-GTA-ATA-AAA-GTG-GTC-CTG-AAA-GCA-TGA-ATA-GTA-GCA-ATT-ACT-GCT-GTG-AAT-TGT-GTT-GTA-ATC-CTG-CTT-GTA-CCG-GGT-GCT-ATT-AAT-AAT-ATA-AAG-GGA-ACT-AAA-CAG-TTC-CCT-TTA-TAT-TTG-TTC-TGA-TTC-TGA-TGA-TGT-CTG-TAA-CGT-ATG-TAC-CTG-TTG-CTT-TGT-TGA-ATA-AA-3′ |

| GenBank accession number used for the insert | M34916.1 |

| Reference | [54] |

| PCR target | Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC) |

| Target gene | aatA gene |

| Detection limit | 1.2 × 101 copies/µL |

| Forward primer | 5′-CAA-TGT-ATA-GAA-ATC-CGC-TGT-T-3′ |

| Reverse primer | 5′-CTG-TCA-GAT-AAA-ATC-TCG-AGA-GAA-3′ |

| Probe and modifications | 5′-Cy5-CATGTTCCTGAGAGTGCAATCCCAG-BHQ2-3′ |

| Positive control plasmid insert | 5′-AGC-TAA-TAA-TGT-ATA-GAA-ATC-CGC-TGT-TTT-ACA-CTC-TTT-TAA-CTT-ATG-ATA-TGT-AAT-GTC-TGG-GAT-TGC-ACT-CTC-AGG-AAC-ATG-ATA-TTC-TCT-CGA-GAT-TTT-ATC-TGA-CAG-TAA-ACT-TTC-CTC-CTC-CTC-AAG-GAC-A-3′ |

| GenBank accession number used for the insert | X81423.1 |

| Reference | [54] |

| PCR target | Arcobacter butzleri |

| Target gene | rpoB/C |

| Detection limit | 3.7 × 102 copies/µL |

| Forward primer | 5′-GCC-ACA-CCA-GTG-ACA-ATA-TC-3′ & 5′-AAA-AAA-TAC-TTT-CTT-GGT-CTT-GTG-GTG-TA-3′ |

| Reverse primer | 5′-AAC-AAC-ACC-TTT-GTA-TCT-CAT-TTT-TTT-G-3′ |

| Probe and modifications | 5′-HEX-TTG-GAC-CAG-TAA-AAG-ATT-ATG-AGT-GTC-TTT-GTG-GTA-AA-BHQ1-3′ |

| Positive control plasmid insert | 5′-GCA-AGT-CCA-GAA-AAA-ATA-CTT-TCT-TGG-TCT-TGT-GGT-GAA-GTT-AAA-AAA-CCT-GAA-ACA-ATT-AAT-TAT-AGA-ACA-TTA-AAA-CCA-GAA-AGA-GAT-GGA-TTA-TTT-TGT-GCT-AAA-ATT-TTT-GGA-CCA-GTA-AAA-GAT-TAT-GAG-TGT-CTT-TGT-GGT-AAA-TAC-AAA-AAA-ATG-AGA-TAC-AAA-GGT-GTT-GTT-TGC-GAA-A-3′ |

| GenBank accession number used for the insert | AB104468.1 |

| Reference | [56,57] |

| Salmonella spp., Shigella spp./EIEC, Campylobacter jejuni PCR | EPEC, ETEC, EAEC PCR | Arcobacter butzleri PCR | |

| Reaction chemistry | |||

| Master Mix | HotStar master mix (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) | HotStar master mix (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) | HotStar master mix (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) |

| Reaction volume (µL) | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 |

| Forward primer concentration (nM) | 750.0 (Salmonella spp.), 375.0 (Shigella spp./EIEC), 125.0 (C. jejuni) | 125.0 | 300.0 |

| Reverse primer concentration (nM) | 750.0 (Salmonella spp.), 375.0 (Shigella spp./EIEC), 125.0 (C. jejuni) | 125.0 | 300.0 |

| Probe concentration (nM) | 42.0 (Salmonella spp.), 21.0 (Shigella spp./EIEC), 35.0 (C. jejuni) | 18.0 (eae gene of EPEC), 35.0 (EAF plasmid of EPEC and aatA gene of EAEC), 70.0 (estB and eltA genes of ETEC) | 100.0 |

| Final Mg2+ concentration (mM) | 3.0 | 6.0 | 4.5 |

| Bovine serum albumin (ng/µL) | - | 2.0 | 5.0 |

| Eluate volume (µL) | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Run conditions | |||

| Initial denaturation | 15 min. at 95 °C | 15 min. at 95 °C | 15 min. at 95 °C |

| Cycle numbers | 45 | 45 | 40 |

| Denaturation | 15 sec. at 95 °C | 15 sec. at 95 °C | 15 sec. at 95 °C |

| Annealing | 20 sec. at 56 °C with a touchdown 13 × 0.5/cycle | 30 sec. at 60 °C | 60 sec. at 60 °C |

| Amplification | 30 sec. at 72 °C | 30 sec. at 72 °C | together with annealing |

| Hold | 30 sec. at 40 °C | 20 sec. at 40 °C | 20 sec. at 40 °C |

References

- Chui, D.W.; Owen, R.L. AIDS and the gut. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1994, 9, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaijee, F.; Subramony, C.; Tang, S.J.; Pepper, D.J. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated gastrointestinal disease: Common endoscopic biopsy diagnoses. Patholog. Res. Int. 2011, 2011, 247923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.D.; Djomand, G.; De Cock, K.M. Natural history and spectrum of disease in adults with HIV/AIDS in Africa. AIDS 1997, 11 (Suppl. B), S43–S54. [Google Scholar]

- Pithie, A.D.; Malin, A.S.; Robertson, V.J. Salmonella and shigella bacteraemia in Zimbabwe. Cent. Afr. J. Med. 1993, 39, 110–112. [Google Scholar]

- Oktedalen, O.; Selbekk, B.; Helle, I.; Heger, B.; Serck-Hanssen, A.; Melby, K. Diagnostikk og behandling av infeksjoner i fordøyelseskanalen ved HIV [Diagnosis and treatment of infections of the digestive system in HIV-infected patients]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 1994, 114, 1416–1420. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, J.S.; Shah, S.S.; Motlhagodi, S.; Bafana, M.; Tawanana, E.; Truong, H.T.; Wood, S.M.; Zetola, N.M.; Steenhoff, A.P. An epidemiologic review of enteropathogens in Gaborone, Botswana: Shifting patterns of resistance in an HIV endemic region. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaisson, R.E. Infections due to encapsulated bacteria, Salmonella, Shigella, and Campylobacter. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 1988, 2, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiq, M.; O’Flanagan, H.; Richardson, D.; Llewellyn, C.D. Factors associated with sexually transmitted shigella in men who have sex with men: A systematic review. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2023, 99, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, C.J.; Kirkcaldy, R.D.; Workowski, K. Enteric Infections in Men Who Have Sex with Men. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 74 (Suppl. 2), S169–S178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, F.; Barber, T. ‘Gay bowel syndrome’: Relic or real (and returning) phenomenon? Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 27, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, J.; Czerwenka, W.; Gruner, E.; von Graevenitz, A. Shigellemia in AIDS patients: Case report and review of the literature. Infection 1993, 21, 122–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kist, M. Chronische Diarrhoe: Stellenwert der Mikrobiologie in der Diagnostik [Chronic diarrhea: Value of microbiology in diagnosis]. Praxis 2000, 89, 1559–1565. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hajra, D.; Nair, A.V.; Chakravortty, D. Decoding the invasive nature of a tropical pathogen of concern: The invasive non-Typhoidal Salmonella strains causing host-restricted extraintestinal infections worldwide. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 277, 127488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taramasso, L.; Tatarelli, P.; Di Biagio, A. Bloodstream infections in HIV-infected patients. Virulence 2016, 7, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2017 Non-Typhoidal Salmonella Invasive Disease Collaborators. The global burden of non-typhoidal salmonella invasive disease: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 1312–1324.

- Uche, I.V.; MacLennan, C.A.; Saul, A. A Systematic Review of the Incidence, Risk Factors and Case Fatality Rates of Invasive Nontyphoidal Salmonella (iNTS) Disease in Africa (1966 to 2014). PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastroeni, P.; Rossi, O. Immunology, epidemiology and mathematical modelling towards a better understanding of invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella disease and rational vaccination approaches. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2016, 15, 1545–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feasey, N.A.; Dougan, G.; Kingsley, R.A.; Heyderman, R.S.; Gordon, M.A. Invasive non-typhoidal salmonella disease: An emerging and neglected tropical disease in Africa. Lancet 2012, 379, 2489–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, L.; Venter, M.; Le Grange, M.; Meel, R. Non-typhoid Salmonella endocarditis complicated by cardiac failure and acute limb ischaemia in a person living with HIV and hepatitis C: A case report and literature review. ID Cases 2023, 32, e01747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talibi Alaoui, Z.; Arabi, F.; Ihbibane, F.; Soraa, N.; Tassi, N. The first description of liver abscesses due to Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica in an African HIV-infected young woman: Case report and review of the literature. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2021, 63, e72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilchrist, J.J.; MacLennan, C.A. Invasive Nontyphoidal Salmonella Disease in Africa. EcoSal. Plus 2019, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lê-Bury, G.; Niedergang, F. Defective Phagocytic Properties of HIV-Infected Macrophages: How Might They Be Implicated in the Development of Invasive Salmonella typhimurium? Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruby, T.; McLaughlin, L.; Gopinath, S.; Monack, D. Salmonella’s long-term relationship with its host. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 36, 600–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monack, D.M. Salmonella persistence and transmission strategies. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2012, 15, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo, F.; Céspedes, A.; Morales, P.; Chanqueo, L. Bacteriemia por Campylobacter jejuni en un paciente con infección por VIH en etapa SIDA [Campylobacter jejuni bacteremia in a patient with HIV infection in AIDS stage]. Rev. Chil. Infectol. 2019, 36, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tee, W.; Mijch, A. Campylobacter jejuni bacteremia in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected and non-HIV-infected patients: Comparison of clinical features and review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1998, 26, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobel, H.; López-Colomes, J.; Saballs, P.; Drobnic, L. Formas inusuales de bacteriemia por Campylobacter jejuni en pacientes con infección por el VIH [Unusual forms of bacteremia due to Campylobacter jejuni in patients with HIV infection]. Med. Clin. 1994, 103, 239. [Google Scholar]

- Wahab, N.; Dubey, V.; Sivachandran, V.; Llewellyn, C.; Richardson, D. Campylobacter spp. in men who have sex with men: A systematic review. Int. J. STD AIDS 2024, 35, 1094–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilmer, A.; Romney, M.G.; Gustafson, R.; Sandhu, J.; Chu, T.; Ng, C.; Hoang, L.; Champagne, S.; Hull, M.W. Shigella flexneri serotype 1 infections in men who have sex with men in Vancouver, Canada. HIV Med. 2015, 16, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frem, J.A.; Russell, A.; Fitzpatrick, C.; Williams, D.; Richardson, D. Gastrointestinal Escherichia coli in men who have sex with men: A systematic review. Int. J. STD AIDS 2025, 36, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D.; Savary-Trathen, A.; Fitzpatrick, C.; Williams, D. Estimated prevalence and associations of sexually transmissible bacterial enteric pathogens in asymptomatic men who have sex with men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2024, 100, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizade, H.; Sharifi, H.; Naderi, Z.; Ghanbarpour, R.; Bamorovat, M.; Aflatoonian, M.R. High Frequency of Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in HIV-Infected Patients and Patients with Thalassemia in Kerman, Iran. J. Int. Assoc. Provid. AIDS Care 2017, 16, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, A.M.; Rivera, F.P.; Romero, L.M.; Kolevic, L.A.; Castillo, M.E.; Verne, E.; Hernandez, R.; Mayor, Y.E.; Barletta, F.; Mercado, E.; et al. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) pediatric patients in Lima, Peru. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010, 83, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okeke, I.N. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in sub-Saharan Africa: Status, uncertainties and necessities. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2009, 3, 817–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, C.; Chincha, O.; Leon, M.; Iglesias, D.; Barletta, F.; Mercado, E.; Ochoa, T. High frequency of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patients with and without diarrhea in Lima, Peru. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010, 82, 1118–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, K.L.; Newman, G.S.; Cybulski, R.J.; Fang, F.C. Gastroenteritis in Men Who Have Sex with Men in Seattle, Washington, 2017–2018. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimesaat, M.M.; Karadas, G.; Alutis, M.; Fischer, A.; Kühl, A.A.; Breithaupt, A.; Göbel, U.B.; Alter, T.; Bereswill, S.; Gölz, G. Survey of small intestinal and systemic immune responses following murine Arcobacter butzleri infection. Gut Pathog. 2015, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baztarrika, I.; Salazar-Sánchez, A.; Hernaez Crespo, S.; López Mirones, J.I.; Canut, A.; Alonso, R.; Martínez-Ballesteros, I.; Martinez-Malaxetxebarria, I. Virulence genotype and phenotype of two clinical isolates of Arcobacter butzleri obtained from patients with different pathologies. Arch. Microbiol. 2023, 205, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.; Queiroz, J.A.; Oleastro, M.; Domingues, F.C. Genotypic and phenotypic features of Arcobacter butzleri pathogenicity. Microb. Pathog. 2014, 76, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levican, A.; Alkeskas, A.; Günter, C.; Forsythe, S.J.; Figueras, M.J. Adherence to and invasion of human intestinal cells by Arcobacter species and their virulence genotypes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 4951–4957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadas, G.; Sharbati, S.; Hänel, I.; Messelhäußer, U.; Glocker, E.; Alter, T.; Gölz, G. Presence of virulence genes, adhesion and invasion of Arcobacter butzleri. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 115, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baztarrika, I.; Wösten, M.M.S.M.; Alonso, R.; Martínez-Ballesteros, I.; Martinez-Malaxetxebarria, I. Genes involved in the adhesion and invasion of Arcobacter butzleri. Microb. Pathog. 2024, 193, 106752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadas, G.; Bücker, R.; Sharbati, S.; Schulzke, J.D.; Alter, T.; Gölz, G. Arcobacter butzleri isolates exhibit pathogenic potential in intestinal epithelial cell models. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 120, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arguello, E.; Otto, C.C.; Mead, P.; Babady, N.E. Bacteremia caused by Arcobacter butzleri in an immunocompromised host. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 1448–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathore, A.; Patel, F.; Gupta, N.; Asiimwe, D.D.; Rollini, F.; Ravi, M. First case of Arcobacter species isolated in pericardial fluid in an HIV and COVID-19 patient with worsening cardiac tamponade. ID Cases 2023, 32, e01771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.J.; Ko, W.C.; Huang, A.H.; Chen, H.M.; Jin, Y.T.; Wu, J.J. Arcobacter butzleri bacteremia in a patient with liver cirrhosis. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2000, 99, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Samie, A.; Obi, C.L.; Barrett, L.J.; Powell, S.M.; Guerrant, R.L. Prevalence of Campylobacter species, Helicobacter pylori and Arcobacter species in stool samples from the Venda region, Limpopo, South Africa: Studies using molecular diagnostic methods. J. Infect. 2007, 54, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kownhar, H.; Shankar, E.M.; Rajan, R.; Vengatesan, A.; Rao, U.A. Prevalence of Campylobacter jejuni and enteric bacterial pathogens among hospitalized HIV infected versus non-HIV infected patients with diarrhoea in southern India. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 39, 862–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Amoyaw, F.; Baden, D.; Durand, L.; Bronson, M.; Kim, A.; Grant-Greene, Y.; Imtiaz, R.; Swaminathan, M. Ghana’s HIV epidemic and PEPFAR’s contribution towards epidemic control. Ghana Med. J. 2019, 53, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eibach, D.; Krumkamp, R.; Hahn, A.; Sarpong, N.; Adu-Sarkodie, Y.; Leva, A.; Käsmaier, J.; Panning, M.; May, J.; Tannich, E. Application of a multiplex PCR assay for the detection of gastrointestinal pathogens in a rural African setting. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfo, F.S.; Eberhardt, K.A.; Dompreh, A.; Kuffour, E.O.; Soltau, M.; Schachscheider, M.; Drexler, J.F.; Eis-Hübinger, A.M.; Häussinger, D.; Oteng-Seifah, E.E.; et al. Helicobacter pylori Infection Is Associated with Higher CD4 T Cell Counts and Lower HIV-1 Viral Loads in ART-Naïve HIV-Positive Patients in Ghana. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eberhardt, K.A.; Sarfo, F.S.; Dompreh, A.; Kuffour, E.O.; Geldmacher, C.; Soltau, M.; Schachscheider, M.; Drexler, J.F.; Eis-Hübinger, A.M.; Häussinger, D.; et al. Helicobacter pylori Coinfection Is Associated with Decreased Markers of Immune Activation in ART-Naive HIV-Positive and in HIV-Negative Individuals in Ghana. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 61, 1615–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INSIGHT START Study Group; Lundgren, J.D.; Babiker, A.G.; Gordin, F.; Emery, S.; Grund, B.; Sharma, S.; Avihingsanon, A.; Cooper, D.A.; Fätkenheuer, G.; et al. Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy in Early Asymptomatic HIV Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 795–807. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, A.; Luetgehetmann, M.; Landt, O.; Schwarz, N.G.; Frickmann, H. Comparison of one commercial and two in-house TaqMan multiplex real-time PCR assays for detection of enteropathogenic, enterotoxigenic and enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2017, 22, 1371–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiemer, D.; Loderstaedt, U.; von Wulffen, H.; Priesnitz, S.; Fischer, M.; Tannich, E.; Hagen, R.M. Real-time multiplex PCR for simultaneous detection of Campylobacter jejuni, Salmonella, Shigella and Yersinia species in fecal samples. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2011, 301, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brightwell, G.; Mowat, E.; Clemens, R.; Boerema, J.; Pulford, D.J.; On, S.L. Development of a multiplex and real time PCR assay for the specific detection of Arcobacter butzleri and Arcobacter cryaerophilus. J. Microbiol. Methods 2007, 68, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, R.; Hahn, A.; Eberhardt, K.A.; Hagen, R.M.; Rohde, H.; Loderstädt, U.; Feldt, T.; Sarfo, F.S.; Di Cristanziano, V.; Kahlfuss, S.; et al. Comparison of the Diagnostic Accuracy of Three Real-Time PCR Assays for the Detection of Arcobacter butzleri in Human Stool Samples Targeting Different Genes in a Test Comparison without a Reference Standard. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanida, K.; Hahn, A.; Frickmann, H. Comparison of two commercial and one in-house real-time PCR assays for the diagnosis of bacterial gastroenteritis. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 2020, 10, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niesters, H.G. Quantitation of viral load using real-time amplification techniques. Methods 2001, 25, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderWeele, T.J.; Mathur, M.B. Some desirable properties of the Bonferroni correction: Is the Bonferroni correction really so bad? Am. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 188, 617–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, R.; Palit, P.; Haque, M.A.; Mahfuz, M.; Faruque, A.S.G.; Ahmed, T. Site specific incidence rate of virulence related genes of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli and association with enteric inflammation and growth in children. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.A.M.; Medeiros, P.H.Q.S.; Havt, A. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli subclinical and clinical infections. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 31, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.A.M.; Soares, A.M.; Filho, J.Q.S.; Havt, A.; Lima, I.F.N.; Lima, N.L.; Abreu, C.B.; Junior, F.S.; Mota, R.M.S.; Pan, W.K.; et al. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli Subclinical Infection and Coinfections and Impaired Child Growth in the MAL-ED Cohort Study. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2018, 66, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogawski, E.T.; Guerrant, R.L.; Havt, A.; Lima, I.F.N.; Medeiros, P.H.Q.S.; Seidman, J.C.; McCormick, B.J.J.; Babji, S.; Hariraju, D.; Bodhidatta, L.; et al. Epidemiology of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli infections and associated outcomes in the MAL-ED birth cohort. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platts-Mills, J.A.; Babji, S.; Bodhidatta, L.; Gratz, J.; Haque, R.; Havt, A.; McCormick, B.J.; McGrath, M.; Olortegui, M.P.; Samie, A.; et al. Pathogen-specific burdens of community diarrhoea in developing countries: A multisite birth cohort study (MAL-ED). Lancet Glob. Health 2015, 3, e564–e575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumkamp, R.; Sarpong, N.; Schwarz, N.G.; Adlkofer, J.; Loag, W.; Eibach, D.; Hagen, R.M.; Adu-Sarkodie, Y.; Tannich, E.; May, J. Gastrointestinal infections and diarrheal disease in Ghanaian infants and children: An outpatient case-control study. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003568, Correction in PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003728. [Google Scholar]

- Platts-Mills, J.A.; Gratz, J.; Mduma, E.; Svensen, E.; Amour, C.; Liu, J.; Maro, A.; Saidi, Q.; Swai, N.; Kumburu, H.; et al. Association between stool enteropathogen quantity and disease in Tanzanian children using TaqMan array cards: A nested case-control study. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2014, 90, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georges-Courbot, M.C.; Beraud-Cassel, A.M.; Gouandjika, I.; Georges, A.J. Prospective study of enteric Campylobacter infections in children from birth to 6 months in the Central African Republic. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1987, 25, 836–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.E.; Elfving, K.; Shakely, D.; Nilsson, S.; Msellem, M.; Trollfors, B.; Mårtensson, A.; Björkman, A.; Lindh, M. Rapid Clearance and Frequent Reinfection with Enteric Pathogens Among Children With Acute Diarrhea in Zanzibar. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 65, 1371–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paintsil, E.K.; Masanta, W.O.; Dreyer, A.; Ushanov, L.; Smith, S.I.; Frickmann, H.; Zautner, A.E. Campylobacter in Africa—A specific viewpoint. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 2023, 13, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | HIV-Positive Individuals, n = 651 | HIV-Negative Individuals, n = 84 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Age in years, median (IQR) | 40 (33/47) | 29 (24/37) |

| Female, n (%) | 469 (73.63) | 53 (64.63) | |

| Socioeconomic parameters | Access to tap water, n (%) | 337 (52.9) | 53 (63.86) |

| Electricity in household, n (%) | 595 (93.41) | 80 (96.39) | |

| Refrigerator in household, n (%) | 463 (72.68) | 68 (81.93) | |

| SES index high, n (%) | 459 (72.06) | 68 (81.93) | |

| Medical parameters | Cotrimoxazole prophylaxis, n (%) | 206 (33.01) | NA |

| Intake of cART, n (%) | 263 (41.29) | NA | |

| Body mass index, median (IQR) | 22 (20/26) | 24 (21/27) | |

| Virological andimmunological parameters | Viral load, log10 copies/mL, median (IQR) | 4.2 (1.6/5.4) | NA |

| CD4+ T cell count/µL, median (IQR) | 347 (145/571) | 949 (767/1168) | |

| CD8+ T cell count/µL, median (IQR) | 970 (648/1379) | 470 (354/710) | |

| CD4+/CD8+ T cell ratio, median (IQR) | 0.4 (0.2/0.7) | 2.0 (1.6/2.5) |

| Ct Values of the Real-Time PCR Assays | ||

|---|---|---|

| Spearman’s ρ | p-Value | |

| Arcobacter butzleri | 0.03 | 0.858 |

| Campylobacter jejuni | −0.11 | 0.692 |

| EAEC | 0.10 | 0.018 |

| EPEC (assay 1 targeting the eae gene) | 0.05 | 0.249 |

| EPEC (assay 2 targeting an EAF plasmid sequence) | −0.18 | 0.058 |

| ETEC | −0.10 | 0.102 |

| Salmonella spp. | 0.19 | 0.078 |

| Shigella spp. | 0.18 | 0.025 |

| Microorganism | Present Study on a Ghanaian Population with HIV | Ghanaian Children [66] | Tanzanian Children [67] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salmonella spp. | Associated with diarrhea | No association with diarrhea detected | No association with diarrhea detected |

| Shigella spp./enteroinvasive Escherichia coli | Associated with diarrhea | Associated with diarrhea | No association with diarrhea detected * |

| Campylobacter jejuni | No association with diarrhea detected | No association with diarrhea detected | No association with diarrhea detected |

| enteropathogenic Escherichia coli | No association with diarrhea detected | Not assessed | No association with diarrhea detected |

| enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli | No association with diarrhea detected | Not assessed | No association with diarrhea detected |

| enteroaggregative Escherchia coli | No association with diarrhea detected | Not assessed | No association with diarrhea detected |

| Arcobacter butzleri | No association with diarrhea detected | Not assessed | Not assessed |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Frickmann, H.; Sarfo, F.S.; Norman, B.R.; Dompreh, A.; Asibey, S.O.; Boateng, R.; Di Cristanziano, V.; Tufa, T.B.; Loderstädt, U.; Binder, R.; et al. Determinants of Entero-Invasive and Non-Entero-Invasive Diarrheagenic Bacteria Among HIV-Positive and HIV-Negative Adults in Ghana. Med. Sci. 2025, 13, 316. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040316

Frickmann H, Sarfo FS, Norman BR, Dompreh A, Asibey SO, Boateng R, Di Cristanziano V, Tufa TB, Loderstädt U, Binder R, et al. Determinants of Entero-Invasive and Non-Entero-Invasive Diarrheagenic Bacteria Among HIV-Positive and HIV-Negative Adults in Ghana. Medical Sciences. 2025; 13(4):316. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040316

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrickmann, Hagen, Fred Stephen Sarfo, Betty Roberta Norman, Albert Dompreh, Shadrack Osei Asibey, Richard Boateng, Veronica Di Cristanziano, Tafese Beyene Tufa, Ulrike Loderstädt, Ramona Binder, and et al. 2025. "Determinants of Entero-Invasive and Non-Entero-Invasive Diarrheagenic Bacteria Among HIV-Positive and HIV-Negative Adults in Ghana" Medical Sciences 13, no. 4: 316. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040316

APA StyleFrickmann, H., Sarfo, F. S., Norman, B. R., Dompreh, A., Asibey, S. O., Boateng, R., Di Cristanziano, V., Tufa, T. B., Loderstädt, U., Binder, R., Zautner, A. E., Luedde, T., Feldt, T., & Eberhardt, K. A. (2025). Determinants of Entero-Invasive and Non-Entero-Invasive Diarrheagenic Bacteria Among HIV-Positive and HIV-Negative Adults in Ghana. Medical Sciences, 13(4), 316. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040316