Exploring the Impact of Emotional Eating Among University Students: A Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

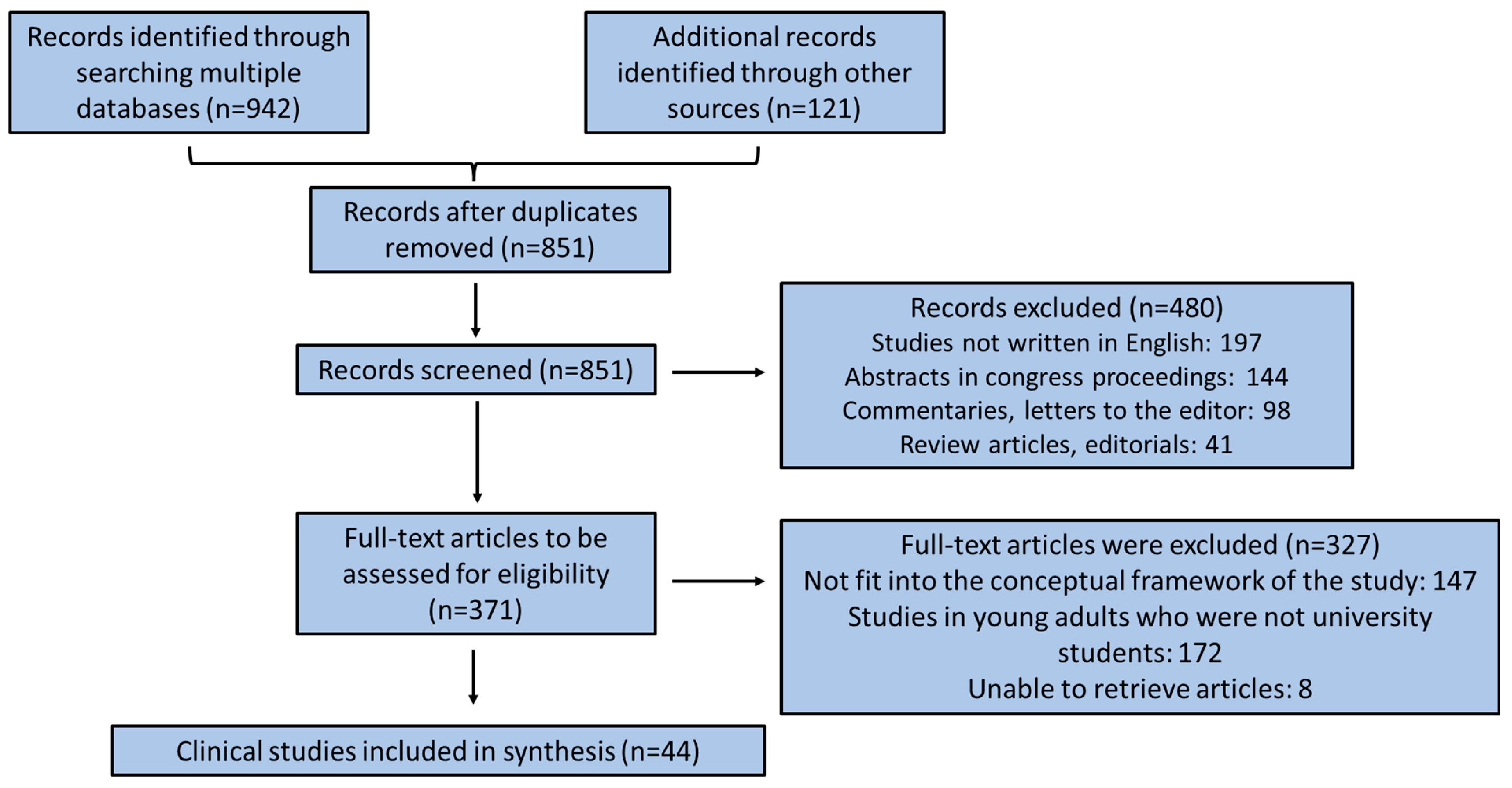

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith, J.; Ang, X.Q.; Giles, E.L.; Traviss-Turner, G. Emotional eating interventions for adults living with overweight or obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meye, F.J.; Adan, R.A. Feelings about food: The ventral tegmental area in food reward and emotional eating. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 35, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, O.; Çamli, A.; Kocaadam-Bozkurt, B. Factors affecting food addiction: Emotional eating, palatable eating motivations, and BMI. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 6841–6848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Power, D.; Jones, A.; Keyworth, C.; Dhir, P.; Griffiths, A.; Shepherd, K.; Smith, J.; Traviss-Turner, G.; Matu, J.; Ells, L. Emotional eating interventions for adults living with overweight and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of behaviour change techniques. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2025, 38, e13410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakanalis, A.; Mentzelou, M.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Papandreou, D.; Spanoudaki, M.; Vasios, G.K.; Pavlidou, E.; Mantzorou, M.; Giaginis, C. The association of emotional eating with overweight/obesity, depression, anxiety/stress, and dietary patterns: A review of the current clinical evidence. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, J.; Marx, W.; Dash, S.; Carney, R.; Teasdale, S.B.; Solmi, M.; Stubbs, B.; Schuch, F.B.; Carvalho, A.F.; Jacka, F.; et al. The effects of dietary improvement on symptoms of depression and anxiety: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychosom. Med. 2019, 81, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.-Q.; Peng, C.-L.; Lian, Y.; Wang, B.-W.; Chen, P.-Y.; Wang, G.-P. Association between dietary inflammatory index and mental health: A systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 662357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnatowska, E.; Surma, S.; Olszanecka-Glinianowicz, M. Relationship between mental health and emotional eating during the COVID-19 pandemic: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaner, G.; Yurtdaş-Depboylu, G.; Çalık, G.; Yalçın, T.; Nalçakan, T. Evaluation of perceived depression, anxiety, stress levels and emotional eating behaviours and their predictors among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health Nutr. 2023, 26, 674–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, H.S.J.; Soong, R.Y.; Ang, W.H.D.; Ngooi, J.W.; Park, J.; Yong, J.Q.Y.O.; Goh, Y.S.S. The global prevalence of emotional eating in overweight and obese populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychol. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, K.L.; Panza, E.; Appelhans, B.M.; Whited, M.C.; Oleski, J.L.; Pagoto, S.L. The emotional eating scale. Can a self-report measure predict observed emotional eating? Appetite 2012, 58, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domoff, S.E.; Meers, M.R.; Koball, A.M.; Musher-Eizenman, D.R. The validity of the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire: Some critical remarks. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2014, 19, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, B.G.; da Silva, W.R.; Maroco, J.; Campos, J.A.D.B. Psychometric characteristics of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire-18 and eating behavior in undergraduate students. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2021, 26, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsson, J.; Persson, L.O.; Sjöström, L.; Sullivan, M. Psychometric properties and factor structure of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ) in obese men and women. Results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) study. Int. J. Obes. Relat. 2000, 24, 1715–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lauzon, B.; Romon, M.; Deschamps, V.; Lafay, L.; Borys, J.M.; Karlsson, J.; Ducimetière, P.; Charles, M.A. The Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire-R18 is able to distinguish among different eating patterns in a general population. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 2372–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Strien, T.; Frijters, J.E.R.; Bergers, G.P.A.; Defares, P.B. The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating behavior. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1986, 5, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebolla, A.; Barrada, J.R.; van Strien, T.; Oliver, E.; Baños, R. Validation of the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) in a sample of Spanish women. Appetite 2014, 73, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaulet, M.; Canteras, M.; Morales, E.; López-Guimera, G.; Sánchez-Carracedo, D.; Corbalán-Tutau, M.D. Validation of a questionnaire on emotional eating for use in cases of obesity: The Emotional Eater Questionnaire (EEQ). Nutr. Hosp. 2012, 27, 645–651. [Google Scholar]

- Putnoky, S.; Serban, D.M.; Banu, A.M.; Ursoniu, S.; Serban, C.L. Reliability and validity of the Emotional Eater Questionnaire in Romanian adults. Nutrients 2022, 15, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella-Zarb, R.A.; Elgar, F.J. The ‘Freshman 5′: A Meta-analysis of weight gain in the freshman year of college. J. Am. Coll. Health 2009, 58, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-González, V.; Arnau-Salvador, R.; Deltell, C.; Mayolas-Pi, C.; Reverter-Masia, J. Physical activity, eating habits and tobacco and alcohol use in students of a Catalan university. Rev. Fac. Med. 2018, 66, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, S.H.; Saeedi, A.A.; Baamer, M.K.; Shalabi, A.F.; Alzahrani, A.M. Eating habits among medical students at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2020, 13, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosevski, D.L.; Milovancevic, M.P.; Gajic, S.D. Personality and psychopathology of university students. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2010, 23, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, P.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Guo, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, P.; Hu, B.; et al. Exploring the interconnections of anxiety, depression, sleep problems and health-promoting lifestyles among Chinese university students: A comprehensive network approach. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1402680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashizawa, R.; Hamaoka, K.; Honda, H.; Yoshimoto, Y. Correlation between psychological stress and depressive symptoms among Japanese university students: A cross-sectional analysis. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2024, 36, 656–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro-González, S.; Garrido-Miguel, M.; Pascual-Morena, C.; Pozuelo-Carrascosa, D.P.; Fernández-Rodríguez, R.; Martínez-Hortelano, J.A.; Mesas, A.E.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. The association between adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and depression and anxiety symptoms in university students: The mediating role of lean mass and the muscle strength index. Nutrients 2025, 17, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heumann, E.; Helmer, S.M.; Busse, H.; Negash, S.; Horn, J.; Pischke, C.R.; Niephaus, Y.; Stock, C. Depressive and anxiety symptoms among university students during the later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany—Results from the COVID 19 German Student Well-being Study (C19 GSWS). Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1459501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, T.B.; Lorenzetti Branco, J.H.; Martins, T.B.; Santos, G.M.; Andrade, A. Impact of social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of university students and recommendations for the post-pandemic period: A systematic review. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2024, 43, 100941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, M.; Mantzorou, M.; Serdari, A.; Bonotis, K.; Vasios, G.; Pavlidou, E.; Trifonos, C.; Vadikolias, K.; Petridis, D.; Giaginis, C. Evaluating Mediterranean diet adherence in university student populations: Does this dietary pattern affect students’ academic performance and mental health? Int. J. Health Plann. Manage 2020, 35, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gull, M.; Kaur, N.; Abuhasan, W.M.F.; Kandi, S.; Nair, S.M. A Comprehensive Review of Psychosocial, Academic, and Psychological Issues Faced by University Students in India. Ann. Neurosci. 2025, 09727531241306571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, N.; Zarei, H.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Ghasemi, H.; Hosseinian-Far, A.; Mohammadi, M. The impact of social networking addiction on the academic achievement of university students globally: A meta-analysis. Public Health Pract. 2025, 9, 100584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szemik, S.; Zieleń-Zynek, I.; Szklarek, E.; Kowalska, M. Prevalence and determinants of overweight or obesity among medical students over a 2-year observation. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1437292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuter, P.R.; Forster, B.L.; Brister, S.R. The influence of eating habits on the academic performance of university students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 69, 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Işik, K.; Cengi, Z.Z. The effect of sociodemographic characteristics of university students on emotional eating behavior. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2021, 57, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohara, K.; Kato, Y.; Mase, T.; Kouda, K.; Miyawaki, C.; Fujita, Y.; Okita, Y.; Nakamura, H. Eating behavior and perception of body shape in Japanese university students. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2014, 19, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amoako, M.; Amoah-Agyei, F.; Du, C.; Fenton, J.I.; Tucker, R.M. Emotional eating among Ghanaian university students: Associations with physical and mental health measures. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Chen, G.; Wu, S.; Niu, R.; Fan, X. Patterns of negative emotional eating among Chinese young adults: A latent class analysis. Appetite 2020, 155, 104808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saritas, M.; Sukut, Ö. The effect of solution-focused group counseling on emotional eating levels in university students: A randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Rep. 2024, 332941241293697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hootman, K.C.; Guertin, K.A.; Cassano, P.A. Stress and psychological constructs related to eating behavior are associated with anthropometry and body composition in young adults. Appetite 2018, 125, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villano, I.; Ilardi, C.R.; Arena, S.; Scuotto, C.; Gleijeses, M.G.; Messina, G.; Messina, A.; Monda, V.; Monda, M.; Iavarone, A.; et al. Obese subjects without eating disorders experience binge episodes also independently of emotional eating and personality traits among university students of southern Italy. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalkowska, J.; Poínhos, R. Eating behaviour among university students: Relationships with age, socioeconomic status, physical activity, body mass index, waist-to-height ratio and social desirability. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawant, N.S.; More, S.R.; Singh, S.D.; Agrawal, A.S.; Chauhan, A. Eating behaviours, social media usage, and its association: A cross-sectional study in Indian medical undergraduates. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2024, 33, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixit, U.; He, J.; Whited, M.; Ellis, J.M.; Zickgraf, H.F. Negative emotional eating patterns among American university students: A replication study. Appetite 2023, 186, 106554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shatwan, I.M.; Alzharani, M.A. Association between perceived stress, emotional eating, and adherence to healthy eating patterns among Saudi college students: A cross-sectional study. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2024, 43, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houminer Klepar, N.; Davidovitch, N.; Dopelt, K. Emotional Eating among College Students in Israel: A Study during Times of War. Foods 2024, 13, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwalska, J.; Kolasińska, K.; Łojko, D.; Bogdański, P. Eating behaviors, depressive symptoms and lifestyle in university students in Poland. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chearskul, S.; Pummoung, S.; Vongsaiyat, S.; Janyachailert, P.; Phattharayuttawat, S. Thai version of Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire. Appetite 2010, 54, 410–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diggins, A.; Woods-Giscombe, C.; Waters, S. The association of perceived stress, contextualized stress, and emotional eating with body mass index in college-aged Black women. Eat. Behav. 2015, 19, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yang, Q.; Luo, J.; Ouyang, Y.; Sun, M.; Xi, Y.; Yong, C.; Xiang, C.; Lin, Q. Association between emotional eating, depressive symptoms and laryngopharyngeal reflux symptoms in college students: A cross-sectional study in human. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Moreno, M.; Garcés-Rimón, M.; Miguel, M.; Iglesias López, M.T. Adherence to Mediterranean Diet, alcohol consumption and emotional eating in Spanish university students. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; He, X.; Tang, Y.; Tang, J.; Yang, J. Unveiling the links between physical activity, self-identity, social anxiety, and emotional eating among overweight and obese young adults. Front. Psychol. 2024, 14, 1255548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J. Impact of stress levels on eating behaviors among college students. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sze, K.Y.P.; Lee, E.K.P.; Chan, R.H.W.; Kim, J.H. Prevalence of negative emotional eating and its associated psychosocial factors among urban Chinese undergraduates in Hong Kong: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Ji, S.; Qu, J.; Bu, Y.; Li, W.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, X.; Fu, X.; Liu, Y. Sleep quality and emotional eating in college students: A moderated mediation model of depression and physical activity levels. J. Eat. Disord. 2024, 12, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalton, E.D. Emotional eating in college students: Associations with coping and healthy eating motivators and barriers. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2024, 31, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchena-Giráldez, C.; Carbonell-Colomer, M.; Bernabéu-Brotons, E. Emotional eating, internet overuse, and alcohol intake among college students: A pilot study with virtual reality. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1400815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J.; Zahry, N.R. Relationships among perceived stress, emotional eating, and dietary intake in college students: Eating self-regulation as a mediator. Appetite 2021, 163, 105215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.; Greene, G.; Schwartz-Barcott, D. Perceptions of emotional eating behavior. A qualitative study of college students. Appetite 2013, 60, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constant, A.; Gautier, Y.; Coquery, N.; Thibault, R.; Moirand, R.; Val-Laillet, D. Emotional overeating is common and negatively associated with alcohol use in normal-weight female university students. Appetite 2018, 129, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klatzkin, R.R.; Nolan, L.J.; Kissileff, H.R. Self-reported emotional eaters consume more food under stress if they experience heightened stress reactivity and emotional relief from stress upon eating. Physiol. Behav. 2022, 243, 113638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poínhos, R.; Oliveira, B.M.P.M.; Correia, F. Psychopathological correlates of eating behavior among Portuguese undergraduate students. Nutrition 2018, 48, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Guo, M.; Wang, J.; Lin, L. The Relationship Between Fears of Compassion, Emotion Regulation Difficulties, and Emotional Eating in College Students: A Moderated Mediation Model. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 780144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grajek, M.; Krupa-Kotara, K.; Białek-Dratwa, A.; Staśkiewicz, W.; Rozmiarek, M.; Misterska, E.; Sas-Nowosielski, K. Prevalence of emotional eating in groups of students with varied diets and physical activity in Poland. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, M.; Ayhan, N.Y.; Çolak, H.; Sarıyer, E.T.; Çevik, E. The effect of chronotype on addictive eating behavior and BMI among university students: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrabec, A.; Yuhas, M.; Deyo, A.; Kidwell, K. Social jet lag and eating styles in young adults. Chronobiol. Int. 2022, 39, 1277–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budkevich, R.O.; Putilov, A.A.; Tinkova, E.L.; Budkevich, E.V. Chronobiological traits predict the restrained, uncontrolled, and emotional eating behaviors of female university students. Chronobiol. Int. 2021, 38, 1032–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos, M.; Elena, B.; Teresa, I.M. Are adherence to the Mediterranean Diet, emotional eating, alcohol intake, and anxiety related in university students in Spain? Nutrients 2020, 12, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, R.M.; Alharbi, H.F. The indicator of emotional eating and its effects on dietary patterns among female students at Qassim university. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Intiful, F.D.; Oddam, E.G.; Kretchy, I.; Quampah, J. Exploring the relationship between the big five personality characteristics and dietary habits among students in a Ghanaian university. BMC Psychol. 2019, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkin, N.; Kütük, H.; Gürol, D.M.; Bilgen, Y.D. The relationship between emotional eating disorders and problematic internet use in university students: The mediating role of mukbang behavior. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2024, 70, e20240343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristanto, T.; Chen, W.S.; Thoo, Y.Y. Academic burnout and eating disorder among students in Monash university Malaysia. Eat. Behav. 2016, 22, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, M.L.; Sprada, G.B.; Hultstrand, K.V.; West, C.E.; Livingston, J.A.; Sato, A.F. Toward a deeper understanding of food insecurity among college students: Examining associations with emotional eating and biological sex. J. Am. Coll. Health 2023, 71, 1463–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Ureña, G.; Renghea, A.; Hernández, S.; Crespo, A.; Fernández-Martínez, E.; Iglesias-López, M.T. Nutritional habits and eating attitude in university students during the last wave of COVID-19 in Spain. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeladita-Huaman, J.A.; Aparco, J.P.; Franco-Chalco, E.; Nateros-Porras, L.; Tejada-Muñoz, S.; Abarca-Fernandez, D.; Jara-Huayta, I.; Zegarra-Chapoñan, R. Emotional impact of COVID-19 and emotional eating and the risk of alcohol use disorder in Peruvian healthcare students. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constant, A.; Fortier, A.; Serrand, Y.; Bannier, E.; Moirand, R.; Thibault, R.; Coquery, N.; Godet, A.; Val-Laillet, D. Emotional overeating affected nine in ten female students during the COVID-19 university closure: A cross-sectional study in France. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eşer Durmaz, S.; Keser, A.; Tunçer, E. Effect of emotional eating and social media on nutritional behavior and obesity in university students who were receiving distance education due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Z Gesundh. Wiss. 2022, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, W.M.; Abdeldaim, D.E. Emotional eating in relation to psychological stress during COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study in faculty of medicine, Tanta University, Egypt. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Type | Study Population | EE Assessment * | Basic Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional study | 537 Turkish university students | EES | EE was positively related to BMI and body weight. Will, anger, BMI, and body weight were predictors of EE. | Isik et al., 2021 [34] |

| Cross-sectional study | 548 Japanese university underweight and normal-weight students | DEBQ | EE was positively associated with BMI. Amongst obese students, women had higher levels of EE than men. | Ohara et al., 2014 [35] |

| Cross-sectional study | 129 Ghanaian university students | TFEQ | EE was related to BMI concerning males and anxiety, and sleep quality regarding females. | Amoako et al., 2023 [36] |

| Longitudinal study | 1068 Chinese university students | AEBQ | Sex and BMI were identified as significant predictors for harmful EE patterns. Students with emotional over- and under-eating had the highest severity concerning eating disorder symptomatology and psychological distress. | He et al., 2020 [37] |

| Randomized controlled experimental study | 55 Turkish university students | DEBQ | A considerable difference was noted between the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up test BMI of those in the experimental group receiving solution-focused counseling compared to those receiving healthy nutrition training. The short-term solution-focused approach was effective in reducing EE levels. | Saritas et al., 2024 [38] |

| Longitudinal study | 173 USA university students | TFEQ | Baseline EE sub-scales were positively associated with baseline weight, BMI, waist circumference, and fat mass index. | Hootman et al., 2018 [39] |

| Cross-sectional study | 266 Italian university students | EOQ | A psychological pattern of increasing overeating behavior and reduced Self-Directedness in combination with increased Sadness and Anger was found. Males presenting elevated perceived stress at university entrance gained considerably higher body weight during the 2nd semester | Villano et al., 2021 [40] |

| Cross-sectional study | 353 Polish university students | TFEQ | A positive association between EE with EE among females was noted. Social desirability was negatively correlated with uncontrolled eating and EE. Amongst males, physical activity had a main effect on EE. | Kowalkowska et al., 2021 [41] |

| Cross-sectional study | 434 Saoudi Arabia university students | EEQ | EE was related to short healthy eating index score and BMI. Academic major was related to perceived stress and EE. | Sawant et al., 2024 [42] |

| Cross-sectional study | 553 USA university students | AEBQ | Emotional over- and under-eating class had the greatest probability of depression, anxiety, stress, and psychosocial impairment because of eating disorder symptoms as well as decreased psychological flexibility. | Dixit et al., 2023 [43] |

| Cross-sectional study | 272 Saoudi university students | TFEQ | A considerable association of increased social media usage with developing abnormal eating behaviors (EE) was reported. | Shatwan and Alzharani, 2024 [44] |

| Cross-sectional study | 575 Isralian university students | Not validated questionnaire | Students having elevated stress and spending more time on social media were shown more often engaging in EE. | Houminer Klepar et al., 2024 [45] |

| Cross-sectional study | 227 Polish university students | TFEQ | BMI, depression, and impulsiveness scores were higher in participants with a high EE score. Emotional eaters were also characterized by higher scores in cognitive restraint and uncontrolled eating components. | Suwalska et al., 2022 [46] |

| Validation study | 89 Thai university students | TFEQ | Restraint and disinhibition scores were more elevated in females compared to males. Restraint and disinhibition scores were also related to body fat but not to BMI. | Chearskul et al., 2010 [47] |

| Cross-sectional study | 99 African American female university students | REBPQ subscales | Perceived stress was correlated with EE. Stress experience may interact with EE to influence BMI. | Diggins et al., 2015 [48] |

| Cross-sectional study | 1301 Chinese university students | TFEQ | Both EE and depression symptoms were related with laryngopharyngeal reflux symptomatology. Female students exhibited more elevated EE scores compared to males. University students whose major was liberal art, with higher BMI, and with low physical activity levels exhibited increased EE scores. | Liu et al., 2020 [49] |

| Cross-sectional study | 584 Spanish university students | EEQ | Almost 38.6% of the students were categorized as eating very emotionally or eating emotionally, and 37.2% were classified as low emotional eaters. EEQ was weakly, positively associated with BMI in female students. | López-Moreno et al., 2021 [50] |

| Cross-sectional study | 373 Chinese overweight and obese university students | EES | Physical activity considerably influenced self-identity and social anxiety that considerably impacted EE. | Wang et al., 2024 [51] |

| Cross-sectional study | 1000 Korean university students | Not validated questionnaire | Female students were found to tend to eat to release stress as a way to decrease this kind of mood. | Choi, 2020 [52] |

| Cross-sectional study | 424 Chinese university students | DEBQ | More than 3-fold greater probability of negative EE was found among females compared with their male counterparts. Having at least mild depressive symptoms was the only independent parameter related to negative EE amongst males. Amongst females, harmful EE was independently associated with depressive symptoms and mild stress. | Sze et al., 2021 [53] |

| Cross-sectional study | 813 Chinese university students | DEBQ | After adjusting for sex, age, and BMI, sleep quality was identified as a predictor factor of EE. Physical activity levels attenuated the association of sleep quality with EE through depression. Depression was also identified as a crucial predictor of EE amongst students with high physical inactivity. | Zhou et al., 2024 [54] |

| Longitudinal study | 232 USA university students | Emotion and Stress-Related Eating subscale of the (EADES) | At baseline, EE was significantly associated with perceived stress, barriers to and motivators of healthy eating, and avoidance coping. Baseline stress levels were not related to EE one year later. | Dalton et al., 2024 [55] |

| Cross-sectional study | 56 Spanish university students | EEQ | EE and internet overuse were associated with impulsivity, depression, and anxiety. Impulsivity and depressive symptoms were responsible for 45% of the EE variance. | Marchena-Giráldez et al., 2024 [56] |

| Cross-sectional study | 523 USA university students | EES | Perceived stress was positively correlated with EE and negatively correlated with eating self-regulation. A positive association between EE and the consumption of sweets and soft drinks was noted. | Ling et al., 2021 [57] |

| Exploratory qualitative study | 16 USA university students | WREQ | Females recognized stress as the main cause for EE, more often followed by guilt. Males were mainly characterized by unpleasant feelings like monotony or anxiety, turning to food as a distraction. | Bennett et al., 2013 [58] |

| Cross-sectional study | 377 French female university students | EOQ and TFEQ | Half of the students reported intermittent emotional overeating in the last 28 days. A positive association of distress-induced overeating with inability to resist emotional cues, disordered eating symptomatology, and loss of control over food consumption was noted. | Constant et al., 2018 [59] |

| Exploratory qualitative study | 43 USA female university students | TFEQ | Self-assessment of EE in the aggregate was not related to enhanced food consumption in response to stress or harmful emotions. | Klatzkin et al., 2022 [60] |

| Cross-sectional study | 258 Portuguese university students | DEBQ | Utmost all eating behaviors’ dimensions (all except external eating and flexible control in the male group) were considerably ascribed to BMI and psychopathological disorders. | Poínhos et al., 2018 [61] |

| Cross-sectional study | 673 Chinese university students | DEBQ | A positive association of fear of compassion for self and fear of compassion from others with emotional regulation problems, which, in turn, were associated with EE for female students, was noted. For male students, merely a positive association of fear of compassion for self with emotional regulation problems was noted. | Zhang et al., 2021 [62] |

| Cross-sectional study | 300 Polish university students | TFEQ | Students presenting higher BMI, no healthy nutritional habits, reduced levels of physical activity, who underestimated meal size concerning weight and calories, and exhibited enhanced-stress feelings were more probable of developing EE. | Grajek et al., 2022 [63] |

| Cross-sectional study | 850 Turkish university students | TFEQ | An increase in BMI of students was associated with a reduction of 25.6% in the TFEQ scores. The students’ BMI and TFEQ scores depended by their MEQ scores. | Arslan et al., 2022 [64] |

| Cross-sectional study | 372 USA university students | TFEQ | Social jet lag considerably predicted reduced intuitive eating and greater EE. Sleep quality significantly predicted intuitive eating, EE, and loss of control overeating. | Vrabec et al., 2022 [65] |

| Cross-sectional study | 567 female Russian university students | TFEQ | Cognitive eating restraint and uncontrolled eating were associated with the morning subscale. EE was associated with the evening subscale MEQ. | Budkevich et al., 2021 [66] |

| Cross-sectional study | 252 Spanish university students | EEQ | State-anxiety was an identified predictive factor of the emotional eating score and its subscales, and gender was identified as a predictive factor of subscale guilt and the total emotional eating score. | Carlos et al., 2020 [67] |

| Cross-sectional study | 380 Saudi Arabia female university students | EES | Fat intake and educational level were substantially related to emotional eating, and they may be significant predictor factors of EE. | Alharbi et al., 2023 [68] |

| Cross-sectional study | 400 Ghanian university students | EES | A considerable percentage of females compared to males were emotional eaters. Fat consumption was a crucial predictive factor of EE and feelings of enthusiasm. | Intiful et al., 2019 [69] |

| Cross-sectional study | 483 Turkish university students | EEDS | EE was positively associated with mukbang addiction and problematic internet use. | Elkin et al., 2024 [70] |

| Longitudinal study | 132 Malaysian university students | TFEQ | EE scores were substantially different over levels of academic burnout next to 6–8 weeks. | Kristanto et al., 2016 [71] |

| Cross-sectional study | 232 USA university students | EES | Food insecurity was positively associated with EE. The above relationship was higher in male compared to female students. | Frank et al., 2023 [72] |

| Cross-sectional study | 161 Spanish female university students | EEQ | Emotional eaters compared to not emotional eaters showed low food addiction, a considerably enhanced consumption of carbohydrates, fat, and alcohol during the last wave of COVID-19 pandemia. | Díaz-Ureña et al., 2024 [73] |

| Cross-sectional study | 456 Peruvian university students | MEQ** | EE was associated with the overall emotional effect of COVID-19, BMI, depression and anxiety levels, and living with only one parent. | Zeladita-Huaman et al., 2024 [74] |

| Cross-sectional study | 302 French female university students | EOQ | Emotional overeating positively correlated with internal monotony proneness, smoking, attentional impulsivity, lack of ability to avoid emotional cues, and control loss over food consumption and harmfully with age and well-being during COVID-19 lockdown. | Constant et al., 2023 [75] |

| Cross-sectional study | 1000 Turkish university students | EES | EE, eating behavior, and BMI were influenced in students receiving distance education due to social media use throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. | Eser Durmaz et al., 2022 [76] |

| Cross-sectional study | 250 Egyptian university students | EES | COVID-19 pandemia, especially throughout the intervals of lockdown, had a harmful effect on people’s psychological stress and EE behaviors. | Shehata et al., 2023 [77] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alexatou, O.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Mentzelou, M.; Deligiannidou, G.-E.; Dakanalis, A.; Giaginis, C. Exploring the Impact of Emotional Eating Among University Students: A Literature Review. Med. Sci. 2025, 13, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13020056

Alexatou O, Papadopoulou SK, Mentzelou M, Deligiannidou G-E, Dakanalis A, Giaginis C. Exploring the Impact of Emotional Eating Among University Students: A Literature Review. Medical Sciences. 2025; 13(2):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13020056

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlexatou, Olga, Sousana K. Papadopoulou, Maria Mentzelou, Georgia-Eirini Deligiannidou, Antonios Dakanalis, and Constantinos Giaginis. 2025. "Exploring the Impact of Emotional Eating Among University Students: A Literature Review" Medical Sciences 13, no. 2: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13020056

APA StyleAlexatou, O., Papadopoulou, S. K., Mentzelou, M., Deligiannidou, G.-E., Dakanalis, A., & Giaginis, C. (2025). Exploring the Impact of Emotional Eating Among University Students: A Literature Review. Medical Sciences, 13(2), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13020056