Readmission Events Following EGD for Upper Gastrointestinal Bleed: An Analysis Using the National Readmission Database

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bai, L.; Jiang, W.; Cheng, R.; Dang, Y.; Min, L.; Zhang, S. Does Early Endoscopy Affect the Clinical Outcomes of Patients with Acute Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gut Liver 2023, 17, 566–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagesh, V.K.; Pulipaka, S.P.; Bhuju, R.; Martinez, E.; Badam, S.; Nageswaran, G.A.; Tran, H.H.V.; Elias, D.; Mansour, C.; Musalli, J.; et al. Management of gastrointestinal bleed in the intensive care setting, an updated literature review. World J. Crit. Care Med. 2025, 14, 101639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, A.J.; Laine, L. Management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. BMJ 2019, 364, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perisetti, A.; Kopel, J.; Shredi, A.; Raghavapuram, S.; Tharian, B.; Nugent, K. Prophylactic pre-esophagogastroduodenoscopy tracheal intubation in patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. Proc. 2019, 32, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, A.K.; Hoversten, P.; Leggett, C.L. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding: Etiologies and management. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2019, 94, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fouad, T.R.; Abdelsameea, E.; Abdel-Razek, W.; Attia, A.; Mohamed, A.; Metwally, K.; Naguib, M.; Waked, I. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding in Egyptian patients with cirrhosis: Post-therapeutic outcome and prognostic indicators. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 34, 1604–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biecker, E. Diagnosis and therapy of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. World J. Gastrointest. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 6, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Menachem, T.; Decker, G.A.; Early, D.S.; Evans, J.; Fanelli, R.D.; Fisher, D.A.; Fisher, L.; Fukami, N.; Hwang, J.H.; Ikenberry, S.O.; et al. Adverse events of upper GI endoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2012, 76, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkun, A.N.; Almadi, M.; Kuipers, E.J.; Laine, L.; Sung, J.; Tse, F.; Leontiadis, G.I.; Abraham, N.S.; Calvet, X.; Chan, F.K.; et al. Management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: Guideline recommendations from the international consensus group. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 171, 805–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.Y.; Yu, Y.; Tang, R.S.; Chan, H.C.; Yip, H.C.; Chan, S.M.; Luk, S.W.; Wong, S.H.; Lau, L.H.; Lui, R.N.; et al. Timing of endoscopy for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1299–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, P.; Spínola, A.; Correia, J.F.; Pereira, A.M.; Nora, M. The Predictive Value of Glasgow-Blatchford Score: The Experience of an Emergency Department. Cureus 2023, 15, e34205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatten, K.; Purssell, H.; Banerjee, A.K.; Soteriadou, S.; Ang, Y. Glasgow Blatchford Score and risk stratifications in acute upper gastrointestinal bleed: Can we extend this to 2 for urgent outpatient management? Clin. Med. 2018, 18, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivieri, S.; Carron, P.N.; Schoepfer, A.; Ageron, F.X. External validation and comparison of the Glasgow-Blatchford score, modified Glasgow-Blatchford score, Rockall score and AIMS65 score in patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding: A cross-sectional observational study in Western Switzerland. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 2023, 30, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.W.; Song, Y.W.; Tak, D.H.; Ahn, B.M.; Kang, S.H.; Moon, H.S.; Sung, J.K.; Jeong, H.Y. The AIMS65 Score Is a Useful Predictor of Mortality in Patients with Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Urgent Endoscopy in Patients with High AIMS65 Scores. Clin. Endosc. 2015, 48, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunne, C.L.; Kaur, S.; Delacruz, B.; Bresee, L.C. 30-day readmission rates among upper gastrointestinal bleeds: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 38, 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, S.; Sharma, S.; Aziz, M.; Ehrlich, D.; Perumpail, M.; Sciarra, M.; Tabibian, J.H. Impact of Readmission for Variceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: A Nationwide Analysis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2022, 67, 2087–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abougergi, M.S.; Peluso, H.; Saltzman, J.R. Thirty-Day Readmission Among Patients With Non-Variceal Upper Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage and Effects on Outcomes. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strömdahl, M.; Helgeson, J.; Kalaitzakis, E. Emergency readmission following acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 29, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.K.; Anugwom, C.; Campbell, J.; Wadhwa, V.; Gupta, N.; Lopez, R.; Shergill, S.; Sanaka, M.R. Early esophagogastroduodenoscopy is associated with better outcomes in upper gastrointestinal bleeding: A nationwide study. Endosc. Int. Open 2017, 5, E376–E386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, N.; Tapper, E.B.; Patwardhan, V.R.; Ketwaroo, G.A.; Thaker, A.M.; Leffler, D.A.; Feuerstein, J.D. Risk factors for adverse outcomes in patients hospitalized with lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2015, 90, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daðadóttir, S.M.; Ingason, A.B.; Hreinsson, J.P.; Björnsson, E.S. Comparison of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with and without liver cirrhosis. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 59, 1081–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjonilla, M.; Chiu, A.; Hameed, N.; Zhang, X.; Khan, M.; Sun, E.; Mizrahi, J. Risk factors associated with 30-day readmission rates in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2024, 99, AB417–AB418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapaskar, N.; Pang, A.; Werner, D.A.; Sengupta, N. Resuming Anticoagulation Following Hospitalization for Gastrointestinal Bleeding Is Associated with Reduced Thromboembolic Events and Improved Mortality: Results from a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2021, 66, 554–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marlicz, W.; Loniewski, I.; Koulaouzidis, G. Proton pump inhibitors, dual antiplatelet therapy, and the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2022, 97, 648–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Franchis, R.; Bosch, J.; Garcia-Tsao, G.; Reiberger, T.; Ripoll, C.; Abraldes, J.G.; Albillos, A.; Baiges, A.; Bajaj, J.; Bañares, R.; et al. Baveno VII–renewing consensus in portal hypertension. J. Hepatol. 2022, 76, 959–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, A.S.; Thuluvath, P.J. The Role of Endoscopy for Primary and Secondary Prophylaxis of Variceal Bleeding. Gastrointest. Endosc. Clin. 2024, 34, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, D.E.; Ripoll, C.; Thiele, M.; Fortune, B.E.; Simonetto, D.A.; Garcia-Tsao, G.; Bosch, J. AASLD Practice Guidance on risk stratification and management of portal hypertension and varices in cirrhosis. Hepatology 2024, 79, 1180–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, S.; Naga, Y.M.; Liu, J.; Dai, M.; Yang, S.; Wang, L.; Ye, B. Esophageal Variceal Ligation Monotherapy versus Combined Ligation and Sclerotherapy for the Treatment of Esophageal Varices. C. J. Gastroente. Hepatol. 2021, 2021, 8856048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Feng, Y.; Sun, L.H.; Zhang, B.J.; Yao, H.J.; Qiao, J.G.; Zhang, S.F.; Zhang, P.; Liu, B. Role of argon plasma coagulation in treatment of esophageal varices. World J. Clin. Cases 2021, 9, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukund, A.; Vasistha, S.; Jindal, A.; Patidar, Y.; Sarin, S.K. Emergent rescue transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt within 8 h improves survival in patients with refractory variceal bleed. Hepatol. Int. 2023, 17, 954–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, L.; Barkun, A.N.; Saltzman, J.R.; Martel, M.; Leontiadis, G.I. Correction to: ACG Clinical Guideline: Upper Gastrointestinal and Ulcer Bleeding. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 116, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddique, S.M.; Hettinger, G.; Dash, A.; Neuman, M.; Mitra, N.; Lewis, J.D. The Role of Hospital Characteristics in Clinical and Quality Outcomes for Gastrointestinal Bleeding in a National Cohort. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 119, 1616–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilicki, D.J.; Reeves, M.J. Outpatient follow-up visits to reduce 30-day all-cause readmissions for heart failure, COPD, myocardial infarction, and stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2024, 21, E74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.H.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Sohn, C.H.; Ahn, S.; Seo, D.W.; Kim, W.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Lim, K.S. Outcomes and role of urgent endoscopy in high-risk patients with acute nonvariceal gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 16, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viderman, D.; Seri, E.; Aubakirova, M.; Abdildin, Y.; Badenes, R.; Bilotta, F. Remote monitoring of chronic critically ill patients after hospital discharge: A systematic review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Population Characteristics (%) | Index Admissions for GI Bleed That Underwent EGD | 30-Day Readmissions for Recurrent GI Bleed |

|---|---|---|

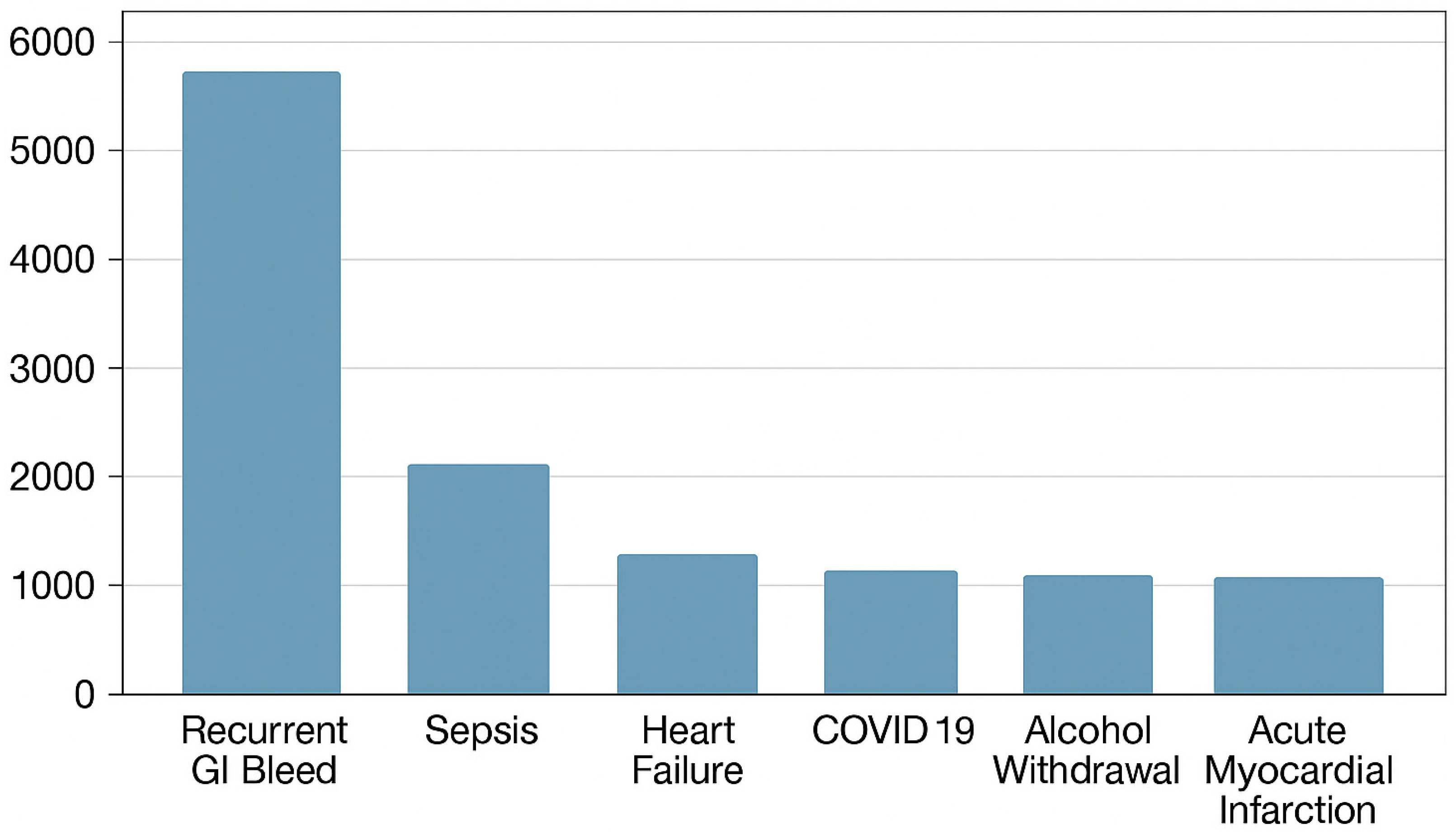

| Total number | 34,257 | 5423 |

| Mean age | 67.63 (67.47–67.79) | 68.46 (67.91–69.02) |

| Sex | Male: 52.57% | Male: 53.40% |

| Female: 47.43% | Female: 46.60% | |

| Quarterly income | 1st Quartile: 28.82% | 1st Quartile: 29.77% |

| 2nd Quartile: 27.06% | 2nd Quartile: 25.88% | |

| 3rd Quartile: 24.50% | 3rd Quartile: 23.26% | |

| 4th Quartile: 19.63% | 4th Quartile: 21.08% | |

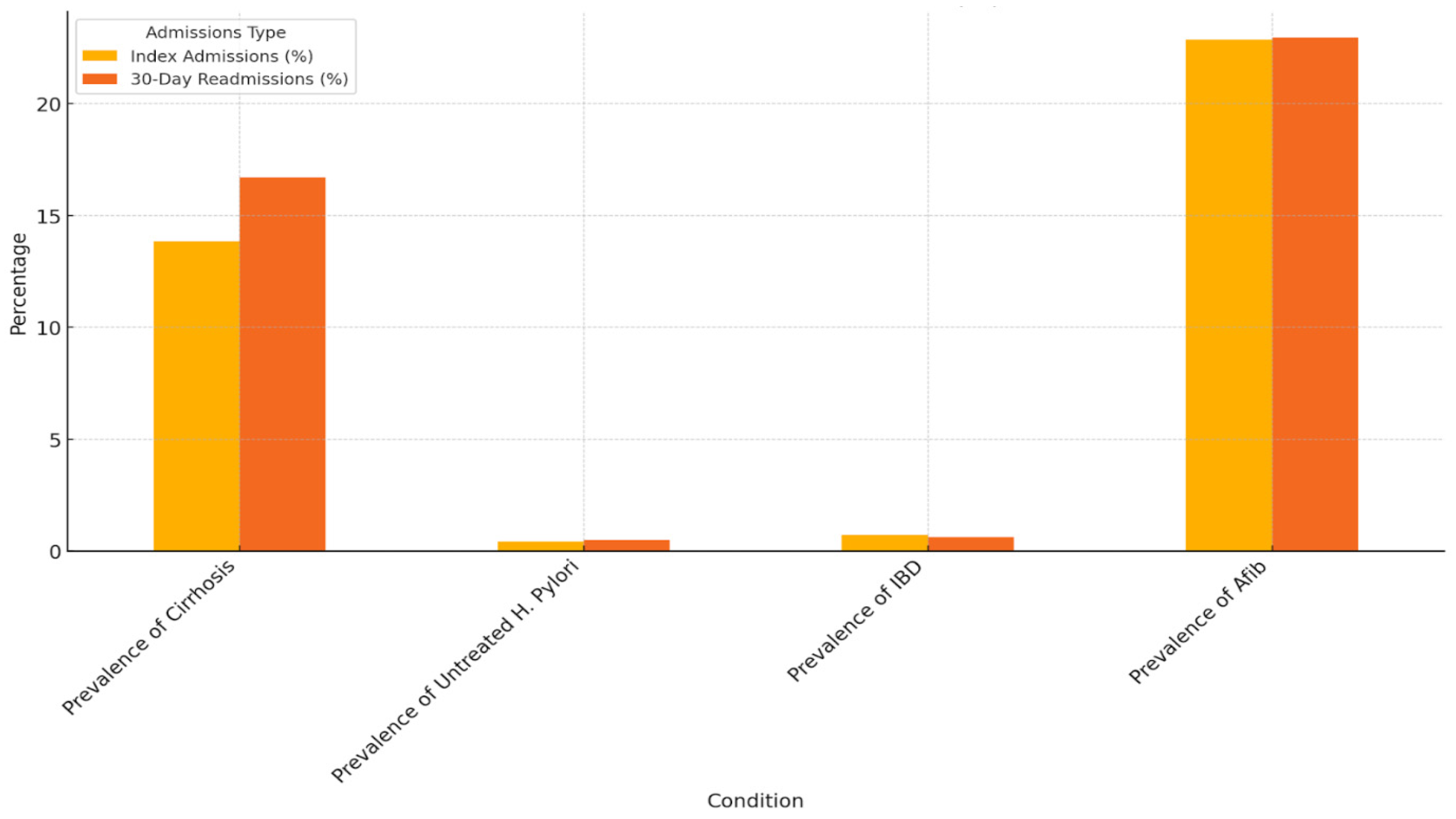

| Prevalence of cirrhosis | 13.84% (13.48–14.21%) | 16.71% (15.31–18.21%) |

| Prevalence of alcohol abuse | 6.10% (5.85–6.36%) | 6.09% (5.22–7.09%) |

| Prevalence of use of chronic anticoagulation | 24.83%% (24.38–25.29%) | 19.70% (18.20–21.29%) |

| Prevalence of use of antiplatelet/antithrombotic agents | 8.90% (8.60–9.21%) | 7.98% (6.99–9.10%) |

| Index Admissions for GI Bleed | 30-Day Readmissions for Recurrent GI Bleed | |

|---|---|---|

| All-cause mortality prevalence (%) | 3.53% (3.41–3.65%) | 1.46% (1.30–1.63%) |

| Mean of total hospital charges (USD) | 61,521.17 (60,681.86–62,360.48) | 82,544.82 (80,796.39–84,293.26) |

| Mean length of hospital stay (days) | 4.97 (4.91–5.02) | 5.38 (5.31–5.45) |

| Population Characteristics (%) | Index Admissions for GI Bleed that Underwent EGD | 30-Day Readmissions for Recurrent GI Bleed |

|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of cirrhosis | 13.84% (13.48–14.21%) | 16.71% (15.31–18.21%) |

| Prevalence of untreated H. Pylori | 0.42% (0.36–0.50%) | 0.51% (0.29–0.87%) |

| Prevalence of IBD | 0.73% (0.65–0.83%) | 0.63% (0.38–1.02%) |

| Prevalence of afib | 22.86% (22.42–23.31%) | 22.96% (21.37–24.64%) |

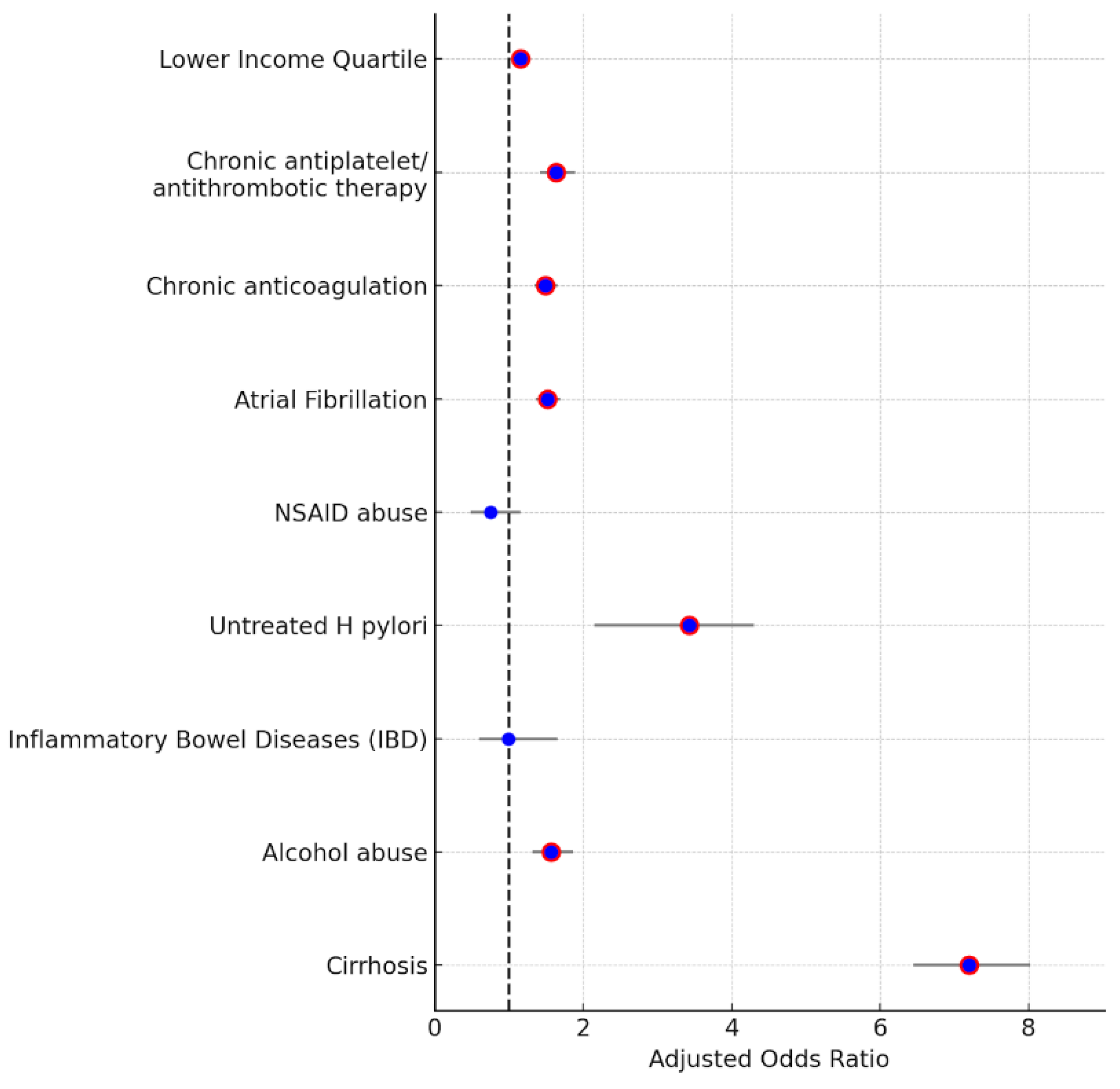

| Patient Characteristics | Adjusted Odds Ratio of Association | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Cirrhosis | 7.199 | (6.45–8.02) |

| Alcohol abuse | 1.571 | (1.32–1.86) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) | 0.992 | (0.597–1.649) |

| Untreated H pylori | 3.43 | (2.15–4.3) |

| NSAID abuse | 0.75 | (0.48–1.15) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.52 | (1.36–1.69) |

| Chronic anticoagulation | 1.49 | (1.35–1.65) |

| Chronic antiplatelet/antithrombotic therapy | 1.63 | (1.41–1.89) |

| Lower income quartile (1st quartile of monthly income) | 1.15 | (1.05–1.25) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nagesh, V.K.; Varughese, V.J.; Musalli, J.; Nageswaran, G.A.; Russell, E.; Feldman, S.A.; Weissman, S.; Atoot, A. Readmission Events Following EGD for Upper Gastrointestinal Bleed: An Analysis Using the National Readmission Database. Med. Sci. 2025, 13, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13020045

Nagesh VK, Varughese VJ, Musalli J, Nageswaran GA, Russell E, Feldman SA, Weissman S, Atoot A. Readmission Events Following EGD for Upper Gastrointestinal Bleed: An Analysis Using the National Readmission Database. Medical Sciences. 2025; 13(2):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13020045

Chicago/Turabian StyleNagesh, Vignesh Krishnan, Vivek Joseph Varughese, Jaber Musalli, Gomathy Aarthy Nageswaran, Erin Russell, Susan Anne Feldman, Simcha Weissman, and Adam Atoot. 2025. "Readmission Events Following EGD for Upper Gastrointestinal Bleed: An Analysis Using the National Readmission Database" Medical Sciences 13, no. 2: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13020045

APA StyleNagesh, V. K., Varughese, V. J., Musalli, J., Nageswaran, G. A., Russell, E., Feldman, S. A., Weissman, S., & Atoot, A. (2025). Readmission Events Following EGD for Upper Gastrointestinal Bleed: An Analysis Using the National Readmission Database. Medical Sciences, 13(2), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13020045