Abstract

This study offers a detailed assessment of the geosites and mining sites present in the Zaruma- Portovelo mining district (Ecuador) through their qualitative and quantitative assessment. It shows up the potentiality of this area taking advantage of its geological-mining heritage. The methodological process includes: (i) compilation and inventory of all the sites within the study area with particular geological or mining interest; (ii) preparation of reports and thematic cartography, (iii) assessment and classification of the elements of geological-mining interest; (iv) SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) analysis and TOWS (Threats, Opportunities, Weaknesses, Strengths) matrix preparation seeking strategies to guarantee the viability of geotourism. A total of 16 sites of geological interest and 11 of mining interest were identified. The 77% of these sites was proved to be of high and very high interest in scientific terms. Likewise, their susceptibility to degradation assessed from their vulnerability and fragility was found to be high or very high in the 30% of the cases. As for the protection priority, all the studied sites obtained a medium-high result. Finally, the study based on the SWOT-TOWS revealed the possibility of applying action strategies in order to facilitate the compatibility of geotourism with the current productive activities, despite the difficult situation in the study area created by mining activities.

1. Introduction

The word and the concept of “geodiversity” was first introduced in the early nineties [1,2]. The term, coined as an analogue to biodiversity [3], has become increasingly common, and it mainly appears in relation to geological heritage and conservation [4,5]. Nevertheless, it has not always been used with the same meaning. For [6] geodiversity is “the number and variety of structures (sedimentary, tectonic, geological materials (minerals, rocks, fossils and soils)), that constitute the substratum in a region, above which the organic activity is settled, the anthropic included”. This definition focuses on the geological features leaving space for the possibility of the development of anthropic activities. On the other hand, [7] considers geodiversity as the diversity of the geographical space and defines it as “the diversity coming from the nature itself (physical-geographical environment) and from the social processes, such as production, settlement and circulation (the human being and its activities)”, considering human activities (e.g., mining) as part of geodiversity. According to [4], the question regarding whether geodiversity should be included in geographical diversity or excluded from it poses practical problems, and therefore geodiversity should be considered as an intrinsic part and a characteristic feature of the territory. As part of the territory, it would relate directly to the geography, landscape, climate, culture and economy of the area. The study of geodiversity, limited to strictly geological features (geology, topography, geomorphology, hydrogeology and soils), represents the base from which relationships between other features and the geological heritage can be developed.

The geological heritage is defined as the group of geological elements with outstanding scientific, cultural and educational values [4,5,8,9,10]. Even though the terms “geological heritage” and “geodiversity” are related to each other and they are both subject to assessment of interest and quality, the study of geological heritage is independent from that of geodiversity. The latter does not consider the variety, frequency and distribution of geological-geomorphological features. Some authors, such as [11], maintain that the geological heritage is a representative example of the geodiversity of a given site. Geological heritage is formed by all those places or points of geological interest, defined as sites or geosites that stand out from their surroundings due to their scientific and/or educational value.

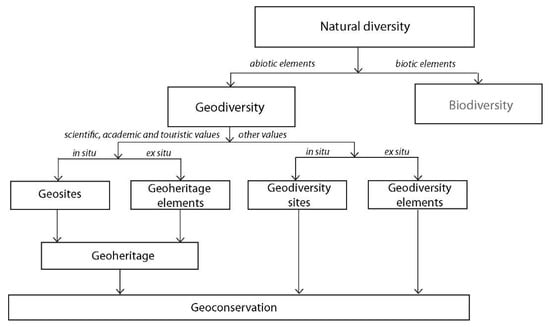

Usually, only a small fraction of the geodiversity has a relevant value to justify the application of geoconservation measures, regardless of whether this fraction is considered geological heritage or not [12]. According to [13], geoconservation strategies should be applied to the characterization and management of every feature of geodiversity that shows any kind of value. A simplified conceptual framework explaining and correlating geodiversity and its main components, within the domain of natural diversity (geosites, geoheritage elements, geodiversity sites and geodiversity elements) [12], is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of geodiversity, geological heritage and geoconservation Modified from [9].

Many governmental programs (e.g., Geoheritage-federal-programs, USA) aim to preserve the sites that are considered the most valuable in terms of their geodiversity especially if they are classified as geological heritage. These programs are generally referred to as geoconservation programs [12,14,15]. The development of an inventory of geosites should be the first step of every strategy pursuing geological heritage conservation. The implementation of conservation and interpretation without a complete inventory of geosites is an inappropriate beginning for any geoconservation project [16]. Creating a protected area is, in most of the countries, a long and complicated bureaucratic process. Thus, this effort must only be applied to those geosites, which stand out due to their scientific, academic and touristic values. To assess this importance, a sound national inventory is essential. After creating an inventory of geosites, the following steps in the geoconservation strategy must be their characterization by assessing their relevance, their protection according to the national legal framework, their preservation, interpretation, and monitoring [12].

Another concept directly related to geologic heritage or geoheritage is “mining heritage”. It can be defined as the total surface and subsurface mining works, hydraulic and transport facilities, machinery, documents or objects related to former mining activities with a historical, cultural or social value [17]. There are several places on the Earth with outstanding geomining features (mining sites) [18] that found a way to benefit from these singular historic and touristic values and use them for local development. Among these cases are Ouro Preto and Diamantinita in Brazil, Cerro Rico de Potosí in Bolivia, Las Escombreras in Sardinia or the Kurkur-Dungul area in Egypt [18,19,20].

In terms of appreciation of geology and landscape, travelling to areas of either great natural beauty or unique geographical phenomena is not something new. Nevertheless, the concept of geotourism [21] appeared in the nineties as “geological” rather than “geographical” tourism. Geotourism, regarded as geographical tourism, was first reported by the National Geographic Society [22]. Thus, geotourism can be seen as a branch of tourism based on geographical location and geological nature that attributes “sense of place” to the area [14,23]. Geotourism understands, promotes and appreciates the environment. It recognizes the importance of geological and climatic phenomena also as a determinant factor in the biotic environment [17,24,25]. Nevertheless, if geotourism lacks the adequate control and prevision, it can itself pose a threat to nature [25].

The region studied here is located in Southern Ecuador. It is a mining district where activity goes back to the Pre-Columbian era. It has a great potential as a touristic destination due to its areas of geological and mining interest, among other aspects. However, the situation of uncontrolled mining activity in the area, currently limited by legal restrictions, calls for alternatives favoring the socioeconomic development while respecting the environment and the territory. On the basis of the above, the aim of this work is to examine the potentiality of geotourism in Zaruma-Portovelo through the inventory, description and assessment of the outstanding geological and mining features in the area (sites of geological and mining interest) while exploring solutions to the environmental and socioeconomic problems related to gold mining. It is important to consider that Zaruma-Portovelo area was selected for this study due to its significance as gold deposit in Ecuador, its relevant geological-mining heritage and, principally, cultural heritage.

2. Geographic and Geological Setting

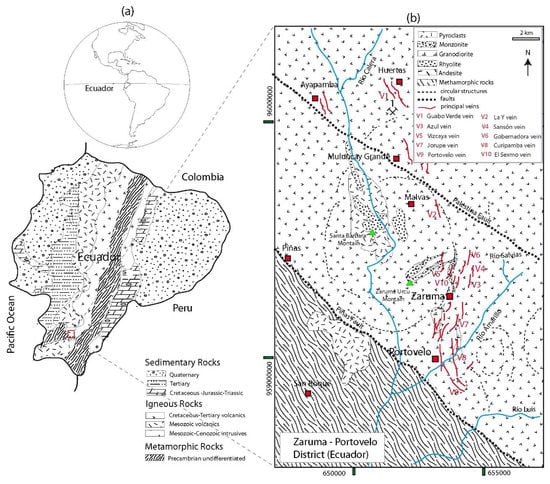

The study area lies in Southern Ecuador (Figure 2a), in the higher part of El Oro province (municipalities of Zaruma and Portovelo), and it is known as Zaruma-Portovelo mining district. The extension of the area of interest is approximately 1000 km2 and its average elevation is around 1200 m. The area is located in the western part of the Andean Mountains (Chilla Cordillera) and within the medium-high section of the Puyango River basin. From a geological point of view, this zone is characterized mainly by the presence of continental-volcanic, plutonic and metamorphic rocks (Figure 2b). Furthermore, the predominant structures (faults) follow an E-W direction, and thus are discordant with the septentrional and eastern Andean system, in which the predominant direction is NNE [26,27,28]. Morphologically, the most remarkable feature is the mountain relief, characterized fundamentally by noticeable fluvial incisions and by the absence of stratovolcanoes [29], very common in the Andean Mountains.

Figure 2.

(a) Simplified geological map of Ecuador and location of selected area; and (b) geological map of Zaruma-Portovelo gold field with basic geology (volcanic and intrusive rocks), principal structures and most important veins. Modified from [28] with data from [30].

It is an argentiferous polymetallic, epigenetic mineral deposit with an epithermal character, in which the ore occurs in seams [28,29,30]. The mining activity in the Zaruma-Portovelo region traces its origins back to the Pre-Columbian era and continues nowadays. Along with the ongoing development of a planned exploitation methods (using modern equipment and machinery for the extraction, grinding, crushing, transportation and recovery processes) promoted by mining companies and associations, there still exists unofficial and uncontrolled mining activity in the area. This poses a serious threat to the natural resources and to the human activities [31,32]. Facing these circumstances, apart from politics limiting this kind of exploitation, it is necessary to consider alternative economic enterprises, such as geotourism, that are compatible with the planned activities under development (mining, agriculture, ranching and tourism).

3. Methodology

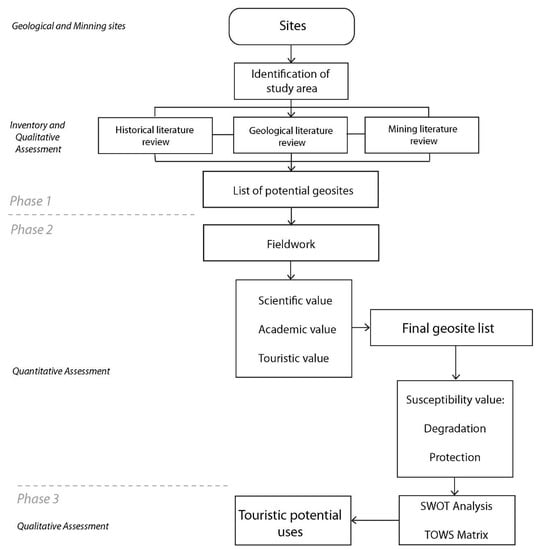

The procedure followed in this study is divided into three different phases (Figure 3) adopting the methods of other previous studies of characterization, assessment and use of areas with singular geological-mining values [12,33]. The scientific value is focused on highlighting the importance of the site from the point of view of its contribution to knowledge advance while the academic value is focused on the ease of transmitting this knowledge to society.

Figure 3.

Scheme of the methodology used for the assessment of the sites (geosites and mining sites). Modified from [12,33]. SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats). TOWS (Threats, Opportunities, Weaknesses, Strengths).

3.1. Information Gathering and Preliminary Analysis

In this phase, all the available information was gathered in a thorough literature review of project reports, theses, articles and scientific publications about the study area [19,20,29]. Furthermore, enquiries were held to local agents (e.g., interviews with the miners and the general population) and also on fieldwork [18,34]. The areas of interest were inventoried and stored in a Geographical Information System (GIS) for their posterior analysis and detailed assessment. As a result of this first phase, an inventory was obtained, containing information about areas of remarkable geological interest (geosites) and mining interest (mining sites). The criterion established to decide whether a site is rather of geological or of mining interest was to consider its most remarkable geological or mining feature.

3.2. Specific Selection and Site Assessment

All the sites of interest listed in the mentioned inventory were studied in detail, including a quantitative assessment of the degree of interest. Even though there are several methods for the specific assessment of the sites with geological or mining interest [12,33,35], here we followed the procedure proposed by [33]. Firstly, the interest of the sites was assessed by three independent experts on the basis of a wide range of parameters (e.g., representativeness, rareness, spectacularity, etc.) listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Assessment procedure of the scientific (Sc.), academic (Ac.) and touristic (To.) interest of a particular site. The indicated values are a theoretical example. Modified from [33]. Interest value rank (0, 1, 2, 3 or 4). Weight (constant values in %). Interpretation: Maximum (400), Very high (267–400), High (134–266), Medium (50–134), Low (<50).

The Table 1 allows calculating the final parameters in an automated manner by combining the values established by experts and the valuation weights described in the scientific literature. The procedure comprised the following elements: (i) the score of the interest criterion established by experts with numerical values 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4 (being 0 the lowest and 4 the highest); (ii) the valuation weights for each criterion, according to the information available in the specialized literature [33]; (iii) the automated calculation of the scientific (Sc), academic (Ac), touristic (To) and total interest degrees. The total degree is the average of the other three values. Furthermore, the results yielded by the numerical assessment (Table 1) allowed us to conduct a qualitative evaluation of the sites.

In relation to conservation, site degradation susceptibility (DS) was assessed as a function of fragility (Fr.) and vulnerability (Vul.) to external threats. Furthermore, protection priority (Pp) was determined on the basis of the DS and total interest values. The analysis of a series of criteria, such as the size of site or threats, served as input for these assessments. The complete list of parameters considered in the study is listed in Table 2 along with the sheet that allows the automated calculation of the final parameters (Fr., Vul., and DS) by combining assessment values given by experts with the valuation weights described in the scientific literature [33], similar to the procedure followed in Table 1.

Table 2.

Assessment procedure of the fragility (Fr.), vulnerability (Vul.) and degradation susceptibility (DS) of a particular site. The indicated values are a theoretical example. For Fr and Val., values range from 0 to 4. Weight (constant values in %). Interpretation of DS: Very high (200–400), High (68–199), Medium (13–67), Low (<13). Maximum (400). Interpretation of Pp: Very high (113–400), High (17–113), Medium (1–16), Low (0). Maximum (400). Modified from [33].

Degradation susceptibility assessment was conducted taking into consideration the following results: (i) fragility and vulnerability scores given by experts with numerical values between 0 and 4 (0 the lowest and 4 the highest); (ii) valuation weights for every criterion, in accordance with the information available in specific literature [33]; (iii) calculated values of fragility and vulnerability degree and of degradation susceptibility (multiplying the values of fragility and vulnerability and then dividing the result by 400), by using a calculation sheet. Once established the degree of interest and the degradation susceptibility, we have calculated the scientific, academic, touristic and protection priorities (Pp) using formulae (1)–(4) (Table 2).

Pp (Sc) = (ISc)2 × SD × (1/4002)

Pp (Ac) = (IAc)2 × SD × (1/4002)

Pp (To) = (ITo)2 × SD × (1/4002)

Pp = ((ISc + IAc + ITo)/3)2 × SD × (1/4002)

3.3. Diagnosis and Proposal for Geotourism

A diagnosis, through the analysis of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) was applied taking into account the list of assessed sites of geological and mining interest. The SWOT analysis was developed with the participation of several representatives from the public and private sectors, and also from the general public, aiming to gather a significant sample of opinions. This phase of the work pursued to redefine the geotourism potential of the area including criteria that describe the relationship between local society and the geological and mining potential.

4. Results

4.1. Inventory of Sites

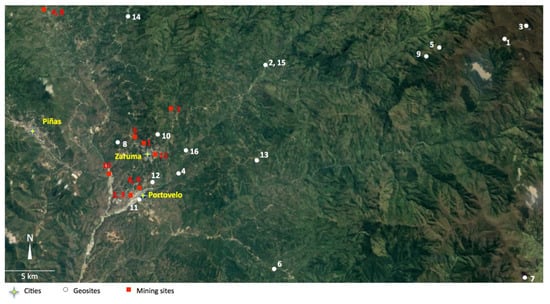

As baseline information, available data of 52 elements of potential touristic, scientific and academic interest were considered. As the result of a first selection, 27 locations were chosen, and then defined as geosites or mining sites (Table 3 and Figure 4), considering their characteristic features (either geological or mining). Table 3 lists the 16 potential geosites including mountains, rivers and waterfalls with a marked geological nature (Figure 5). In the case of the mining sites, 11 potential places of interest were identified, among which mines and mining facilities stand out (Figure 6). This inventory served as a starting point to gauge the potential of the area and to carry out a more exhaustive assessment afterwards.

Table 3.

List of potential geosites and mining sites identified in the study area.

Figure 4.

Location of the geosites and mining sites identified in the Zaruma-Portovelo mining district. [36].

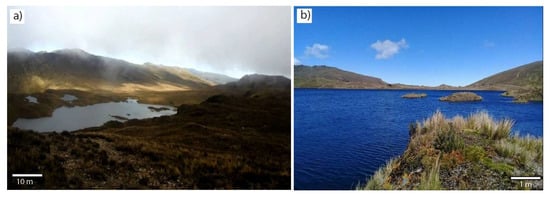

Figure 5.

Example of geosite (e.g., Laguna de Chinchilla) inventoried in the study area. (a) Panoramic view [37], (b) detailed view.

Figure 6.

Example of mining site (e.g., Mina el Sexmo) inventoried in the study area. (a) Mine entrance, (b) underground passage [38], (c) mineralization inside the mine.

4.2. Assessment of the Selected Geosites and Mining Sites

In this phase of the study, the scientific, didactic and touristic/recreational interests were assessed, following the described procedure.

In Table 4, the resulting scores are listed in decreasing order according to the mean value of the interests (scientific, academic and touristic). In accordance with the value rank presented in Table 1:

Table 4.

Assessment of the degree of interest of the geosites and mining sites (*). Scientific (Sc), Academic (Ac), Tourism (To) and Average.

- one site (4%) is of very high interest. It is a mining site.

- twenty sites (74%) are considered of high interest, of which 15 are geosites (75%), and 5 are mining sites (25%).

- six sites (22%) are considered of medium interest, of which one is a geosite (17%), whereas the remaining 5 are mining sites (83%).

- none of the proposed sites is considered to have a low interest, which proves the great relevance of the selected sites in the Zaruma-Portovelo district.

Next, the 27 selected sites were assessed in terms of fragility and vulnerability. The degradation susceptibility was calculated from these two parameters. The combination of degradation susceptibility and interest permitted the evaluation of the protection priority, Pp, of the sites. In Table 5, the results are listed in decreasing order according to degradation susceptibility and protection priority values.

Table 5.

Susceptibility and Protection Priority assessment of the geosites and mining sites (*). Fragility (Fr.), Vulnerability (Vul.), Degradation Susceptibility (DS), Protection Priority (Pp).

According to the classification described in Table 2, all the geosites and mining sites have high degradation susceptibility (DS):

- Two sites (7%) have very high DS. They are both mining sites.

- Fifteen sites (56%) have high DS. Seven of these sites are mining sites (47%) whereas the remaining eight are geosites (53%).

- Ten sites (37%) have a medium DS. Only one of them is a mining site (10%).

- There are no sites with low DS.

The combination of degradation susceptibility and interest allows the determination of the protection priority (Pp). The results listed in Table 5 reveal that the geosites and mining sites have a medium-high protection priority:

- Six sites (22%) present a high Pp index, of which 5 are mining sites (83%).

- Twenty-one sites (78%) present a medium Pp index, 16 of which are geosites (76%) and 5 are mining sites (24%).

- None of the analyzed sites have either low or very high Pp values.

In general, the results demonstrate the existence of geological singularities as well as an important mining legacy, both with a real potential to be exploited in the context of geotourism.

4.3. SWOT Analysis and TOWS Matrix

Together with the inventory and assessment of the geosites and mining sites, a SWOT analysis was performed (Table 6) in order to determine the strengths, opportunities, weaknesses and threats of the area in geotourism.

Table 6.

SWOT Analysis (internal analysis) de la zona de estudio.

The TOWS matrix tool was used to create strategies (Table 7) by the combination of the internal (Strengths and Weaknesses) and the external features (Opportunities and Threats) identified in the SWOT analysis (Table 6).

It is important to mention that the SWOT and TOWS analyses involve the same basic steps and are likely to produce similar results. The order in which managers think about strengths, weaknesses, threats and opportunities may, however, have an impact on the outcome of the analysis. The SWOT analysis and the TOWS matrix enabled us to establish a series of strategies to guarantee the optimal use of resources including the most appropriate actions for preserving, restoring and divulgating the identified geosites and mining sites. Finally, an attempt was made to establish the foundation for future, more ambitious actions (e.g., proposal for the creation of a geopark named Ruta del Oro).

The outcome of the combined analysis of the internal (strengths and weaknesses) and external features (opportunities and threats) can be summarized in seven general strategies:

- (i)

- To raise awareness about and to promote geosites and mining sites as a basis for alternative tourism (geotourism). Specific programs to develop consciousness about the great importance of these areas as tourist destinations should be created by local public organisms (municipalities), educational centers (schools and high schools) and private companies of the tourism sector.

- (ii)

- To formalize alliances between different sectors to maximize the utilization of these resources. Work committees could identify specific actions to boost the tourism development building on geological and mining resources.

- (iii)

- To steer current infrastructure development policies towards the enhancement and conditioning of these facilities (e.g., roads, drinkable water, recreational areas, signposting, etc.) in the areas of interest.

- (iv)

- To guarantee the preservation and protection of the geological heritage and the geodiversity through the implementation of land management plans. It is fundamental to introduce local legislation regulating the management of the natural areas, in general, and of the geological and mining resources, particularly.

- (v)

- To motivate quality improvement in the current tourism services through the creation of programs ensuring their quality and their long-term maintenance.

- (vi)

- Development of supplementary activities directly linked to tourism through participatory models, especially in related productive activities (agriculture, construction, craftwork, transportation, communications, etc.).

- (vii)

- Implementation of integral programs for the development of specific tourism products and services: adventure tourism and ecotourism, spa and hydrotherapy, cultural and archaeological tourism, etc.

4.4. Proposed Route Including Geosites and Mining Sites

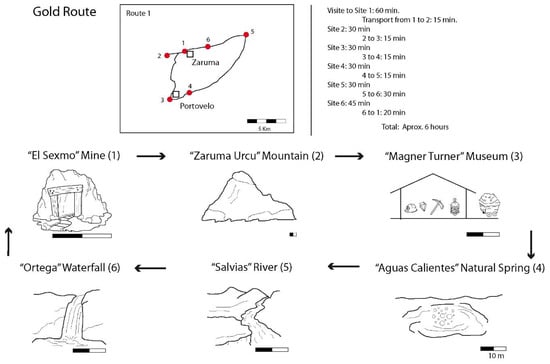

Based on the described data and on previous studies concerning the creation of a geotourism route named “Ruta del Oro” (Gold Route) [19,34,39,40], we propose the development of a specific itinerary of the geosites and mining sites in the area (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Suggested itinerary, within “Ruta del Oro”, selecting several geosites and mining sites.

The proposed itinerary is one example among several potential alternatives considering the sites inventoried in this study. Apart from making the visit to these sites feasible, the route matches the following criteria: (i) accessibility to every selected geosite and mining site with a motor vehicle; (ii) pleasant and attractive tour, as the distance between the sites of interest is not too long. The circuit can be completed in about 6 hours, with the possibility of visiting other sites nearby. A general assessment of the proposed route from the average values of every suggested site is presented in Table 8. The results reveal the significance of this geotourism route and its potential contribution to the regional tourism offer. A complete visit to all the inventoried geosites and mining sites would take approximately 3 days.

Table 8.

Interest, Fr., Vul., DS, and Pp assessment in the context of the proposed route (Figure 7).

5. Discussion

The described methodology [33] enables the assignment of a semi quantitative value to the tourism resources and possibilities of the Zaruma-Portovelo mining district and its surroundings. Particularly, the process made it possible to identify and order the areas of interest from three general points of view: interest, susceptibility and protection [12]. The same approach was used both for the geosites and the mining sites considering that the mining sites are often situated in places with special features of geology, topography, geomorphology, rivers, and a unique landscape and biodiversity [18]. The assessment of these sites of interest pursued to facilitate the practical use of the inventory by all the potential users. The aim of the assessment was: (i) to inform non expert people about the relative value of a site compared to others in the same area, thus allowing the prioritization for use or conservation interventions and (ii) to have distinguishable groups of sites with scientific, didactic or touristic value. According to [41], different assessment methods produce different results. This reveals the need to apply several parallel methods at a given site, since a universal application or a process that allows correlating different values have not been found yet.

The applied SWOT analysis allowed us to relate the geotourism potentiality of areas of geological and mining interest to the existing infrastructure (i.e., roads, hotels, etc.) and ongoing economic activities (mining, agriculture, livestock). Moreover, the TOWS matrix provided important information about the applicability and feasibility of geotourism development and the necessity of relating the entire potentiality of the area (i.e., biodiversity, architecture, customs, culture and history) with the geological and mining heritage [8,10,12,14,15].

Regarding the obtained results, the assessment of the geosites and mining sites evinces: (i) the high interest of the considered areas and (ii) their proximity to each other. A viable alternative to exploit the geosites and mining sites may be the creation of a Geological-Mining Park [17,18,19,42] or, in the first instance, the creation of a Mining Route [39,43] connecting the different areas. The average global values of interest, DS, and Pp (Table 8) of all the sites included in the proposed route (Figure 7) offer a complementary criterion when evaluating different sites of interest in a specific itinerary. In general, the methodology of assessing a route on the basis of individual site values, as the proposed by [33], has proved to be a viable and adequate approach.

The development of proposals for the use of the areas of geological-mining interest, such as the one discussed here (i.e., itinerary to visit geosites and mining sites) would [17,24,25]: (i) foster the protection of the geosites and mining sites, (ii) advance the knowledge of these areas and (iii) offer new economic alternatives for the local population. This would contribute to the improvement of quality of life and to a social development in harmony with the environment [18,43].

In this specific case, the alternative use of geological and mining resources through geotourism would be compatible with the economic activities in the area (mining, agriculture, ranching and tourism). At the same time, if managed correctly, geotourism would benefit the protection of the geological and mining sites of interest [25]. Furthermore, the perspective and development offered by geotourism is an innovative option against the current problems in Zaruma-Portovelo, provoked by a non-regulated and decaying mining activity.

In accordance with [18,19,39], the creation of an official framework, such as a mining route, would allow visitors to learn about the diverse aspects of the geology and auriferous mining in the area in an efficient way. In general, geotourism is a key factor in the socioeconomic development of the local population, enhancing, at the same time, the preservation and protection of the geosites and mining sites [17,24,44].

6. Conclusions

The research presented in this paper reveals the existence of several areas of geological and mining interest in the Zaruma-Portovelo mining district. Following the example of similar initiatives launched in some European countries, these sites could be exploited through the development of geotourism.

In detail, 16 geosites and 11 mining sites were defined in the study area. The interest of geosites reached a score of 153 (high), whereas the interest of mining sites reached an average value of 160 (high). Regarding degradation susceptibility, geosites obtained a rating of 69 (high), whereas for the mining sites this value was 131 (high). The protection priority assessed for geosites reached a score of 11 (medium), and it was 20 (high) in the case of the mining sites.

The SWOT analysis and the TOWS matrix evince that the creation of a Mining Route, a Geological-Mining Park or any other official recognition and/or protection framework for the geosites and mining sites would favor the socioeconomic development in the study area. Nevertheless, it is essential to take adequate legal and financial measures to materialize the viability of the geological and mining uses in any of the aforementioned figures of utilization.

In the Zaruma-Portovelo mining district, the progressive decrease in the gold mining and the problems derived from related activities (environmental issues and terrain destabilization) call for alternative development strategies, such as the one suggested in this paper. Geotourism, as proposed here, represents a sustainable activity, which is also compatible with the current socioeconomic activities in the area. Its implementation can be considered an adequate alternative for socioeconomic and environmental development.

Author Contributions

P.C.M., G.H.F. and J.B. gathered the data of geosites and mining sites, adapted the assessment procedures from the scientific literature and realized the characterization of the sites of interest; P.C., M.J.D.-C. and E.B. completed the geological setting of the studied area and applied analysis tools to grade the different geosites. All the authors wrote this manuscript. E.B. encouraged and supervised the research.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SWOT | Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats |

| TOWS | Threats, Opportunities, Weaknesses, Strengths |

| DS | Degradation Susceptibility |

| Sc | Scientific Interest |

| Ac | Academic Interest |

| To | Touristic Interest |

| Fr | Fragility |

| Vul | Vulnerability |

| Pp | Protection priority |

References

- Sharples, C. A Methodology for the Identification of Significant Landforms and Geological Sites for Geoconservation Purposes; Report; Forestry Commission: Tasmania, Australia, 1993; p. 30.

- Wiedenbein, F.W. Origin and use of the term ‘geotope’ in German-speaking countries. In Geological and Landscape Conservation; O’Halloran, D., Green, C., Harley, M., Knill, J., Eds.; Geological Society: London, UK, 1994; pp. 117–120. [Google Scholar]

- Erikstad, L. Geoheritage and geodiversity management—The questions for tomorrow. Proc. Geol. Assoc. 2013, 124, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcavilla, L.; Durán, J.J.; López-Martínez, J. Geodiversidad: Concepto y Relación con el Patrimonio Geológico. Geo-Temas 2008, 10, 1299–1303. [Google Scholar]

- Carcavilla, L.; Durán, J.J.; Garcia-Cortés, A.; López-Martínez, J. Geological heritage and geoconservation in Spain: Past, present and future. Geoheritage 2009, 1, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, L.M. Geodiversidad: Propuesta de una definición integradora. Bol. Geol. Min. 2001, 112, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, J. Los desafíos del estudio de la geodiversidad. Rev. Geogr. Venez. 2005, 46, 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Brilha, J.B. Património Geológico e Geoconservação: A Conservação da Natureza na sua Vertente Geológica; Palimage Editores: Viseu, Portugal, 2005; p. 190. ISBN 972-8575-90-4. [Google Scholar]

- Lazzari, M. Geosites, cultural tourism and sustainability in Gargano National park (southern Italy): The case of the Salata (Vieste) geoarchaeological site. Rend. Online Soc. Geol. It. 2013, 28, 97–101. [Google Scholar]

- Lazzari, M.; Aloia, A. Geoparks, Geoheritage and Geotourism: Opportunities and Tools in Sustainable Development of the Territory. GeoJ. Tour. Geosites 2014, 13, 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sharples, C. Concepts and Principles of Geoconservation; Tasmanian Parks & Wildlife Service: Hobart, Australia, September 2002; Volume 3, pp. 1–79. Available online: http://dpipwe.tas.gov.au/Documents/geoconservation.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2018).

- Brilha, J. Inventory and quantitative assessment of geosites and geodiversity sites: A review. Geoheritage 2016, 8, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, M.H.; Pena dos Reis, R.; Brilha, J.; Mota, T.S. Geoconservation as an emerging geoscience. Geoheritage 2011, 3, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, J.R. Geotourism’s global growth. Geoheritage 2011, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, M. Geodiversity: Valuing and Conserving Abiotic Nature, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2004; p. 508. ISBN 978-0-470-74215-0. [Google Scholar]

- Fernanda de Lima, F.; Brilha, J.; Salamuni, E. Inventorying Geological Heritage in Large Territories: A Methodological Proposal Applied to Brazil. Geoheritage 2010, 2, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nita, J.; Myga-Piateck, U. Geotourism potential of post-mining regions in Poland. Bull. Geogr. 2014, 7, 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata-Perelló, J.; Carrión, P.; Molina, J.; Villas-Boas, R. Geomining Heritage as a tool to promote the social development of rural communities. In Geoheritage: Assessment, Protection and Management, 3rd ed.; Reynard, E., Brihla, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 167–174. ISBN 978-0-12-809531-7. [Google Scholar]

- Berrezueta, E.; Domínguez-Cuesta, M.J.; Carrión, P.; Berrezueta, T.J.; Herrero, G. Propuesta metodológica para el aprovechamiento del patrimonio geológico minero de la zona Zaruma-Portovelo (Ecuador). Trabajos de Geología 2006, 26, 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Sallam, E.S.; Ponedelnik, A.A.; Tiess, G.; Yashalova, N.N.; Ruban, D.A. The geological heritage of the Kurkur-Dungul area in southern Egypt. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2018, 137, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hose, T.A. Geotourism, or can tourist become casual rock hounds. In Geology on Your Doorstep; Bennet, M.R., Ed.; The Geological Society: London, UK, 1996; pp. 207–228. [Google Scholar]

- Stueve, A.; Cook, S.; Drew, D. The Geotourism Study: Phase 1 Executive Summary. National Geographic Traveller, Travel Industry Association of America. 2002. Available online: https://www.crt.state.la.us/downloads/Atchafalaya/GeoTourismStudy.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2018).

- Dowling, R.K. Geotourism. The Encyclopedia of Sustainable Tourism; CABI: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 231–232. [Google Scholar]

- Hose, T.A. Geotourism and geoconservation. Geoheritage 2012, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, D.; Dowling, R.; Leung, Y. The nature and management of geotourism: A case study of two established iconic geotourism destination. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 2, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaradia, M.; Fontbote, L.; Beate, B. Cenozoic continental arc magmatism and associated mineralizationin Ecuador. Miner. Deposita 2004, 39, 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litherland, M.; Aspen, J.A. Terrane-boundary reactivation: A control on the evolution of the Northern Andes. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 1992, 5, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Thournout, F.; Salemink, J.; Valenzuela, G.; Merlyn, M.; Boven, A.; Muchez, P. Portovelo: A volcanic-hosted epithermal vein-system in Ecuador, South America. Miner. Deposita 1996, 31, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calle, J. Geología regional de Zaruma-Portovelo y consideraciones ambientales del sector. In El Patrimonio Geominero en el Contexto de la Ordenación del Territorio; Martins, L., Carrión, P., Eds.; ESPOL: Guayaquil, Ecuador, 2005; pp. 307–320. ISBN 9978-44-615-. [Google Scholar]

- Berrezueta, E.; Ordóñez-Casado, B.; Bonilla, W.; Banda, R.; Castroviejo, R.; Carrión, P.; Puglla, S. Ore Petrography Using Optiacal Image Analysis: Application to Zaruma-Portovelo Deposit (Ecuador). Geosciences 2016, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrezueta, E. Metodología de Valoración de las Actividades de uso del Suelo en Zaruma-Portovelo. Ecuador; Seminario Internacional de Minería, Metalurgia y Medio Ambiente, Universidad Católica de Lovaina (Bélgica) y Universidad Politécnica Nacional (Ecuador): Quito, Ecuador, 2003; pp. 333–355. [Google Scholar]

- Espí, J.A.; Berrezueta, E. El análisis de la gestión de los recursos naturales: “la huella ecológica” como medida del esfuerzo dela naturaleza. In Agua, Minería y Medio Ambiente. Libro Homenaje al Profesor Rafael Fernández Rubio; López-Geta, J.A., Pulido, A., Baquero, J.C., Eds.; IGME: Madrid, Spain, 2005; pp. 685–706. ISBN 84-7840-574-7. [Google Scholar]

- García-Cortés, A.; Carcavilla, L.; Díaz-Martínez, E.; Vegas, J. Inventario de Lugares de Interés Geológico de la Cordillera Ibérica. 2012, pp. 1–147. Available online: http://www.igme.es/patrimonio/Informe%20Ib%C3%A9rica%20Final.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2018).

- Campoverde, C.; Ramírez, G.; Carrión, P.; Herrera, G. Zaruma-Portovelo: Contexto Geominero de Patrimonio y Diversidad para el Desarrollo Sostenible; IV Congreso Internacional de Geología y Minería Ambiental para el Ordenamiento Territorial y el Desarrollo: Molina de Aragón, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Reynard, E.; Fontana, G.; Kozlik, L.; Scapozza, C. A method for assessing “scientific” and “adicional values” of geomorphosites. Geograp. Helv. 2007, 62, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google Maps. Image of the Zaruma-Portovelo Mining District in Google Maps. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/@-3.6953608,-79.6297901,42481m/data=!3m1!1e3 (accessed on 5 April 2018).

- Viajandox. Chinchilla Lagoon (Image). Available online: https://www.ec.viajandox.com/zaruma/laguna-chinchilla-A1391 (accessed on 5 May 2018).

- El Tiempo. Un Recorrido por 500 Metros de Historia en la Mina El Sexmo, una de las Más Antiguas de Ecuador. Available online: https://www.eltiempo.com.ec/noticias/region/12/un-recorrido-por-500-metros-de-historia-en-la-mina-el-sexmo-una-de-las-mas-antiguas-de-ecuador (accessed on 5 May 2018).

- Campoverde, C.; Ramírez, G.; Carrión, P.; Herrera, G. Potencial Geoturístico-Minero de la Ruta del Oro, Ecuador; IV Congreso Internacional de Geología y Minería Ambiental para el Ordenamiento Territorial y el Desarrollo: Molina de Aragón, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Carrión, P.; Ramos, V.; Ladines, L.; Loayza, G.; Domínguez, J.; Berrezueta, E. La Ruta del Oro y el Patrimonio Geológico-Minero en Zaruma-Portovelo (Ecuador); IV Congreso Internacional Sobre Patrimonio Geológico y Minero, s-2, c-09: Utrillas, Spain, 2003; pp. 333–339. [Google Scholar]

- Strba, L.; Rybár, P.; Baláz, B.; Molokác, M.; Hvizdák, L.; Krsac, M.; Muchova, L.; Tometzová, D.; Ferencíková, J. Geosites assessments: Comparison of methods and results. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 18, 469–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orche, E. Rehabilitación del Patrimonio Minero de Fontao (Villa de Cruces): Propuesta de una Nueva Oferta Lúdica Cultural en Galicia; Congreso Internacional Sobre Patrimonio Geológico e Mineiro: Beja, Portugal, 2001; pp. 291–302. [Google Scholar]

- Carrión, P.; Herrera, G. Proyecto RUMYS: Rutas Minerales y Sostenibilidad. In Rutas Minerales en el Proyecto RUMYS. Un Factor Integral para el Desarrollo Sostenible de la Sociedad; Carrión, P., Ed.; ESPOL: Guayaquil, Ecuador, 2009; pp. 7–17. ISBN 978-9942-02-240-0. [Google Scholar]

- Newsome, D.; Dowling, R. Geoheritage and Geotourism. In Geoheritage: Assessment, Protection and Management, 3rd ed.; Reynard, E., Brihla, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 305–321. ISBN 978-0-12-809531-7. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).