1. Introduction

This present work is devoted to cryoseismological research in the high Tien Shan glacier zone, which is new for Kazakhstan and Central Asia. The research was conducted between 2023 and 2025 as part of the IRN BR21881915 Targeted Funding Program (TFP) “Application of nuclear, seismic and infrasound methods for assessing climate change and mitigating the effects of climate change” by the National Nuclear Center of the Republic of Kazakhstan. The main task was to create a special network of multi-parameter observations for glacial processes and to obtain experimental seismic and infrasound data as a result of joint processing of data from the field and permanent stations of the National Nuclear Center (NNC) network of the Republic of Kazakhstan [

1]. It was necessary to study the capabilities of such a system as a tool for monitoring the dynamics of glacial processes. The results of the assessment of the capabilities of the created system for monitoring glacial seismic activity are presented; seismic and infrasound noise and its connection with meteorological and other factors were studied and estimates of the representative magnitude and energy class of recorded glacial earthquakes were calculated.

In recent years, due to great interest in global warming and its impact on the climate, active research of glaciers has begun both in the Arctic zone and in mountainous regions on the continents. A detailed review of global and local sources on the study of seismic processes in glaciers under the influence of climate change is given in Ref. [

2]. It shows that the worldwide interest in cryoseismological research increased in 2016 after the discovery of glacial earthquakes by Ekström et al. [

3,

4]. The results of subsequent studies by various scientists have shown that changes in daily air temperature generate glacial seismicity. The crevasses and cracks appearing in the ice are fundamental components of the mass balance of glaciers; they serve as pathways for meltwater into the glacial water-bearing system and provide a large amount of latent heat into glaciers. This causes shifts in the glacial mass, and its movement can be recorded by seismic methods. The arrangement of long-term continuous monitoring will make it possible to assess and predict changes in the dynamics of glacial processes as a result of global climate change.

Why is this issue so important and relevant for Kazakhstan? Let us refer to the data published in a new report by an international organization (IKI global program) [

5] published in 2025. It is very important for Kazakhstan to have a comprehensive understanding of the risks associated with water. Water is a key resource and the basis for the social and economic stability of key economic sectors, including agriculture, industry, and energy production. Kazakhstan is experiencing significant impact from climate change, as it influences its environmental, social, and economic landscape.

Over the past six decades, the average annual temperature in Kazakhstan has risen by 0.3 °C per decade. Forecasts indicate a further increase in average annual temperatures. These temperature changes are accompanied by changes in precipitation patterns, exacerbating water-related risks in Kazakhstan, a country that already struggles with water scarcity and uneven distribution of water resources. The water situation in the country is further aggravated by the melting of glaciers in the Tien Shan mountains. In 2020, Kazakhstan experienced record high temperatures, exceeding the climatic norm by 1.92 °C, which surpassed the previous record in 2013 of 1.89 °C. Glaciers in the Tien Shan and Pamir mountains are thus melting at an accelerated rate, and these are sources of water for major rivers such as the Amu Darya and Syr Darya. These changes have contributed to an increase in natural disasters such as droughts, floods, mudflows, and landslides, leading to land degradation, damage to infrastructure, and loss of life. We are witnessing the gradual disappearance of glaciers in the mountains of the Northern Tien Shan; for example, near the city of Almaty in Kazakhstan. The water demand for agriculture needs is predicted to increase, and this is despite the fact that the productivity of irrigation water in Kazakhstan is six to eight times lower than in other countries.

Temperature rises have led to more frequent and intense heat waves across the country, especially in the south, southwest, and west regions. This has affected precipitation patterns, water resources, and agriculture. This warming trend will probably exacerbate the existing problems. Long-term water availability will decline due to the continuing retreat of glaciers and reduction of snow cover in mountainous areas. Measures to adapt to climate change need to be developed: water resource monitoring systems are being introduced, but the set of measures may also include the creation of monitoring and warning systems on glacier dynamics based on multi-parameter monitoring of glacial earthquakes.

2. Materials and Methods

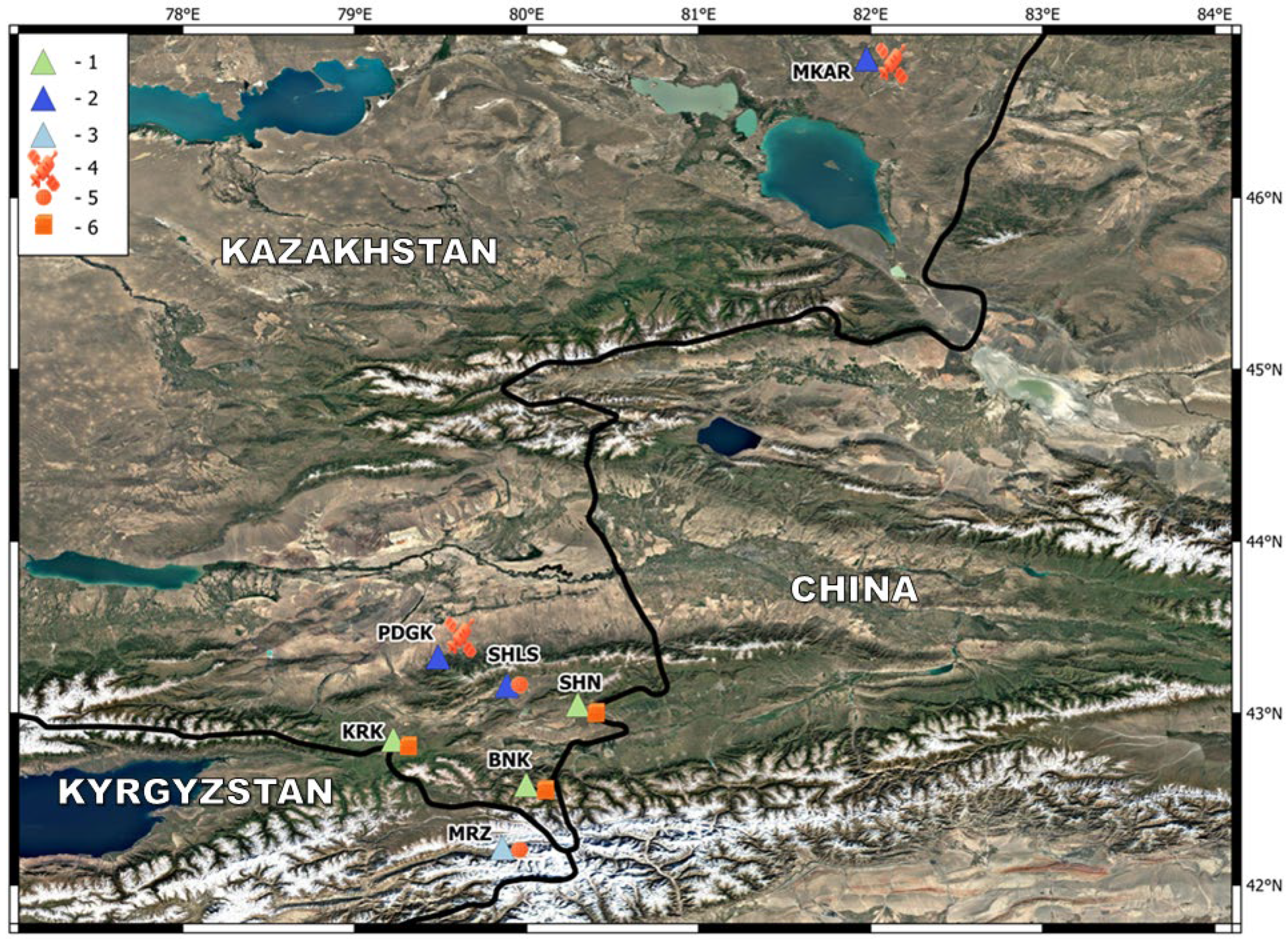

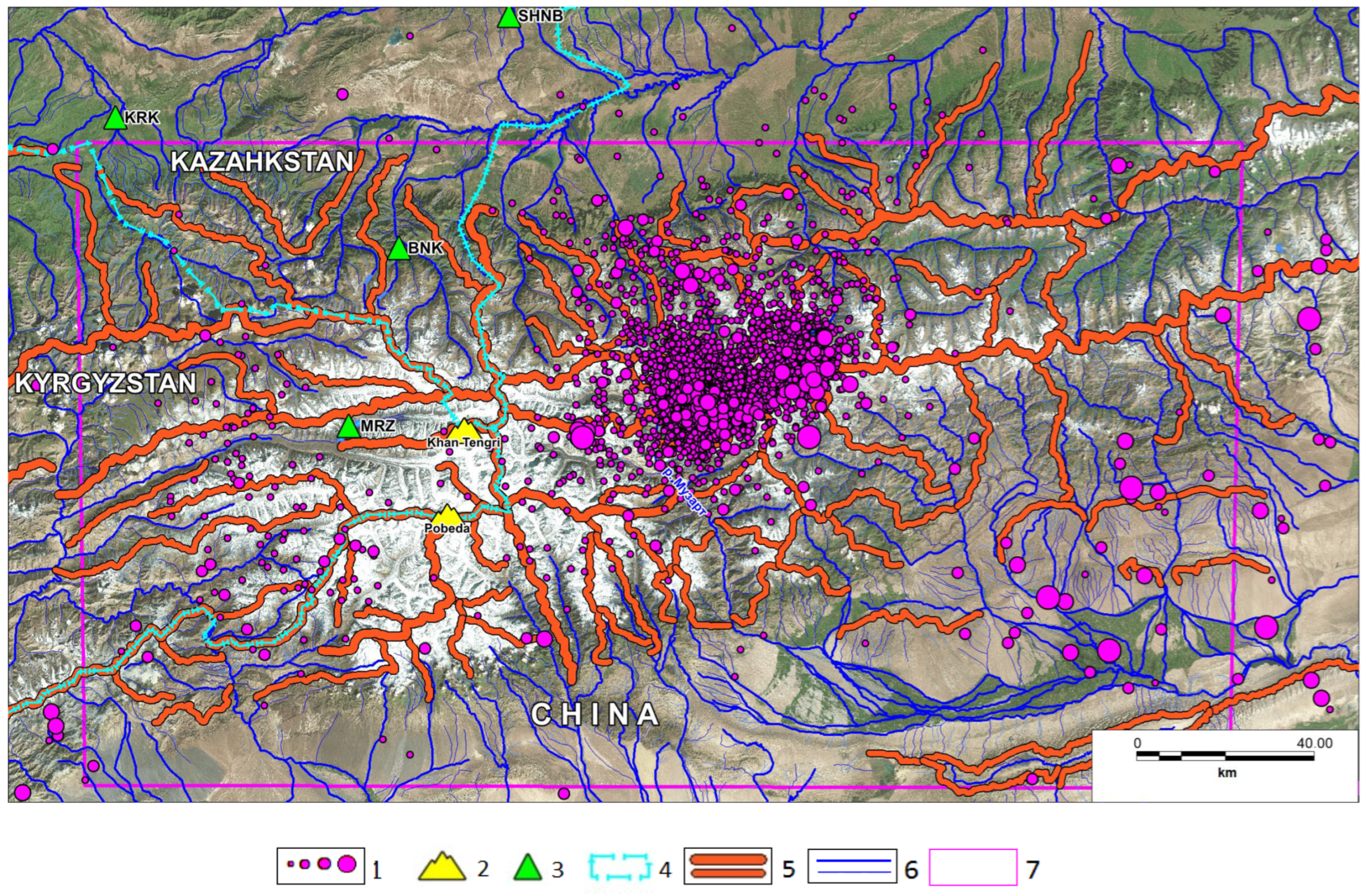

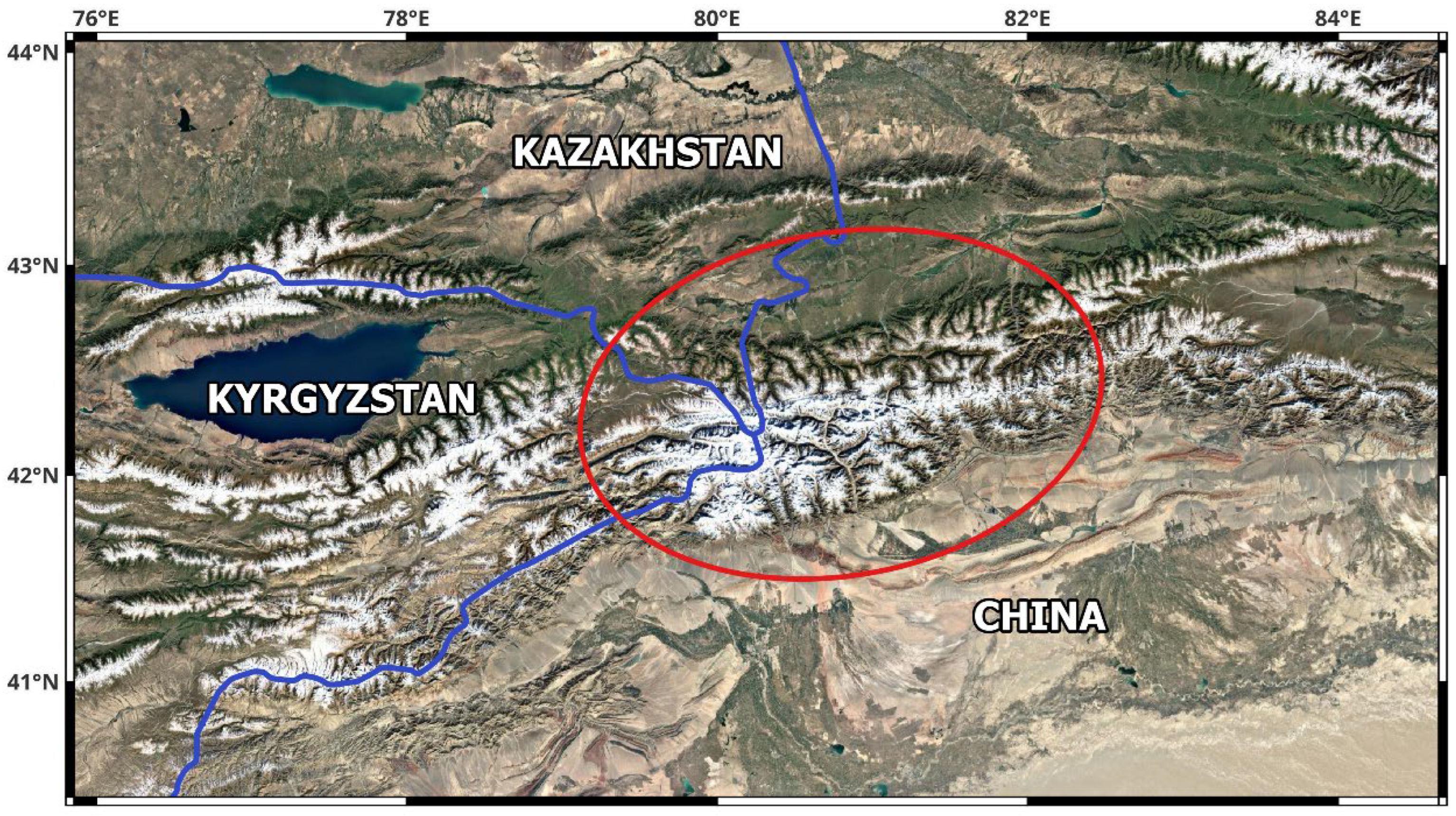

To study glacial earthquakes, the region of high Tien Shan where the borders of three countries—Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and China—converge, was chosen. This area contains the main large-scale glaciers of the high mountainous part of the Tien Shan. The highest mountain peaks of the Tien Shan are located here: Khan Tengri Peak (7010 m) and Pobeda Peak (7439 m). This area is known to seismologists as being seismically active. All recorded earthquakes are up to 60 km in depth, i.e., its epicenters are located in the Earth’s crust. The largest known earthquake in this area occurred in 1716 in China and had a magnitude of M = 7.5. However, no large earthquakes were recorded within the glacier zone.

Figure 1 shows an overview map of the high-mountain Tien Shan glacier research area.

A detailed study of the seismicity in this zone was planned, as well as the determination of the epicenter field structure and seismic mode. Probably, the seismic activity of this zone could be an indicator of glacier destruction as a result of climate change. The main research tool was a network of seismic, infrasound, and meteorological monitoring stations.

Site selection was chosen for instrument installation and the arrangement of observation using field network stations.

To start the cryoseismological monitoring of the selected area, first, it was necessary to carry out reconnaissance studies to select sites for three observation stations installation. This work was carried out from the end of 2023. The sites were selected based on a set of criteria: On the one hand, the stations had to be located as close as possible to glaciers located on the territory of the Republic of Kazakhstan. On the other hand, it was necessary to follow safety measures to protect the equipment from vandalism; thus, the opportunity of placing the stations on private land was assessed. The sites for the stations’ installation had to be characterized by a low level of seismic noise (both natural and human-made), the presence of dense ground, the absence of swampy or water-saturated soil, and in areas affected by tectonic faults. The Kazakhstan National Data Center (KNDC) analyzed the initial reconnaissance data and studied the comparative possibilities of installing stations in different locations for an extended period. The results are summarized as follows: Seismic stations at all three selected sites are sensitive to events generated by glaciers. No infrasound events associated with glacial earthquakes were detected. Negotiations were held and agreements were concluded with security guards and landowners.

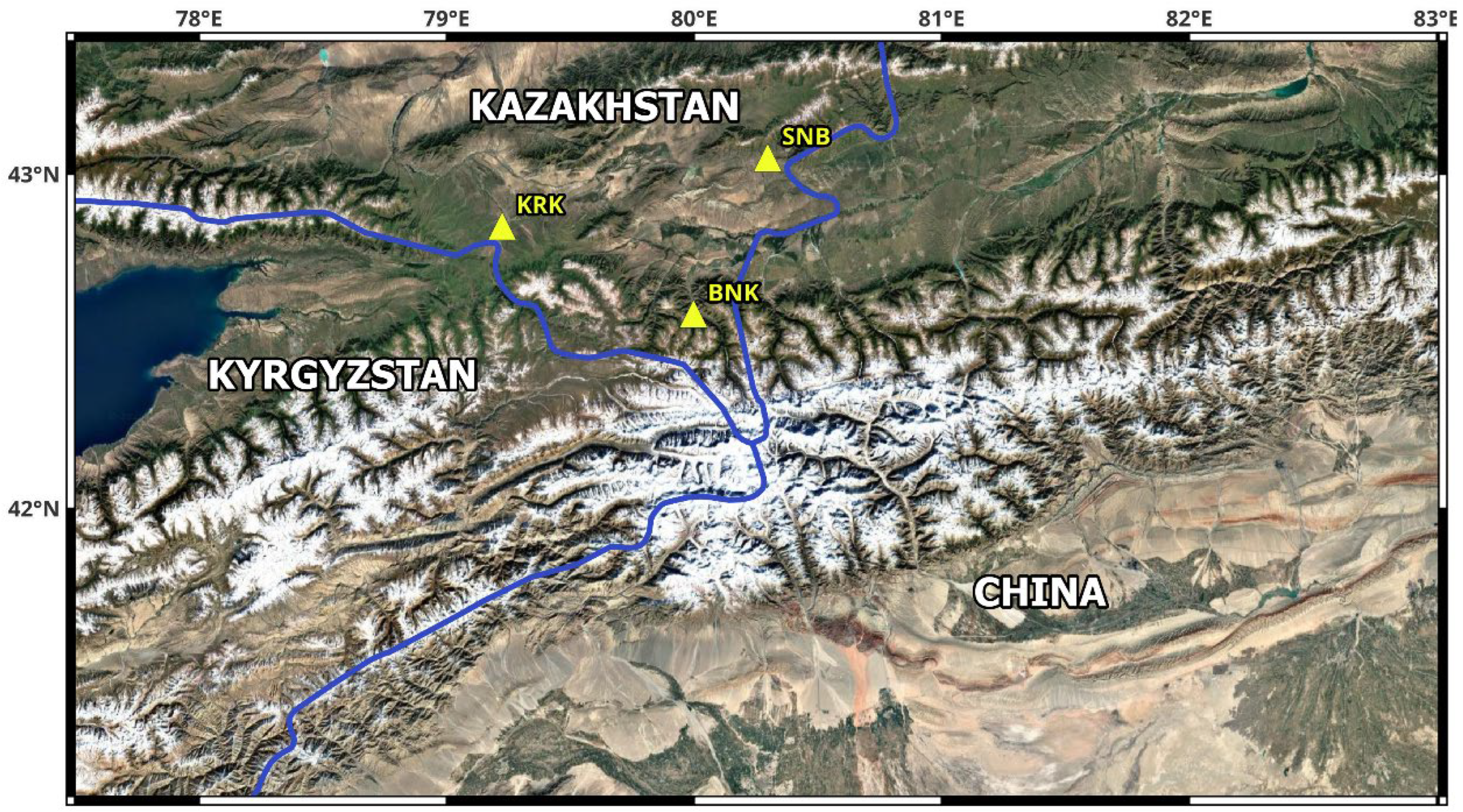

The sites for three stations were selected:

- -

Karkara (KRK) is located 400 m away from Karkara-Tyup highway, 180 m away from the winter camp. The selected site is the lower part of the southeastern slope of gentle hills formed by Neogene deposits (

Figure 2,

Table 1).

- -

Bayankol (BNK) is located in the Bayankol Gorge, Akkol area. The site is a small intermountain valley where two mountain gorges converge. In the northern part of the valley, filled with loose sediments, there is a gentle elevation—a remnant with fragments and outcrops of coarse-grained quartz–feldspar granites (

Figure 2,

Table 1).

- -

Shynybek (SHN) is located 200 m northeast of the winter camp. The selected site consists of Neogene sedimentary deposits; no bedrock outcrops were found. The soil consists of dense grayish-brown clay. At a depth of 0.5 m, there is a heavily gypsum-rich clayey–gravelly weathering crust of grayish-yellowish color with large (up to 20 cm), angular fragments of gypsum-rich tuffs of mixed composition and dark gray color (

Figure 2,

Table 1).

The seismic equipment set, consisting of a DR 4040 recorder, a CMG 40T seismometer, a CMG 5T accelerometer, and an electronic thermometer, was installed at all three stations. Unfortunately, the insufficient amount of available equipment did not allow us to install microbarometers for recording infrasound signals at all stations from the beginning of the observations. At the beginning, there was only one MB2005 microbarometer at our disposal, but later, a second MB 3a microbarometer was purchased and installed. During the course of the work, one GMX weather station was purchased; it was moved sequentially between stations to study wind increases, weather conditions, and the potential for recording infrasound signals generated by the high-mountain glaciers of the Tien Shan.

Figure 3 shows a diagram of the field stations’ operational periods and their equipment to study seismic, infrasound, and meteorological parameters. The diagram shows the periods and stations at which comprehensive studies of seismic, infrasound, and meteorological data are possible.

Before installing the equipment at all stations, some preparatory work was carried out by KNDC: diagnostics of the equipment and the testing of a complete set of seismic stations consisting of a DR 4040 digitizer, a GURALP CMG 40T seismometer, a CMG 5T accelerometer, microbarometers, and a weather station. The following parameters were set for recording seismic oscillations:

Sample rate—100 sample/s.

Amplification—1.

Recording parameter—ground oscillation velocity (nm/s), acceleration of ground oscillations (nm/s2).

Recording format—CSS3.0

Upon completion of the preparation work (site selection, equipment preparation, coordination with local executive bodies, border service, forestry), the equipment installation was carried out, including the preparation of seismic vaults, pedestals, fences, and a test run of the equipment.

Figure 4 shows photographs of the installation of the autonomous power supply system, protective fencing, and a set of seismic recording equipment. The installation of infrasound stations at an altitude of over 1000 m above sea level required changes to the sensitive settings of the MB2005 microbarometer. The microbarometer housing was opened to access the adjustable elements, and the system was adjusted under the control of a multimeter. Thus, the microbarometer was adjusted to operate under the atmospheric pressure conditions of a specific site while maintaining the dynamic range specified by the manufacturer.

To suppress the noise of the MB2005 microbarometer, a noise suppression system consisting of four orthogonal beams, each 6 m long made of plastic tubes with air intakes at the ends in the form of funnels with fine-mesh metal screens inside to prevent small insects from entering the system, was installed. The microbarometer itself, with the noise reduction system connected, was installed in a prepared pit, covered with a thermal box and a shield with a protective film, and then covered with soil.

The stages of the preparation, adjustment, and installation of the microbarometer are shown in

Figure 5.

Equipment operability was examined both on-site during visits to the stations and at the data center. At the stations, the integrity and operability of all equipment was checked, while seismic and infrasound noise levels were analyzed at the data center. Station maintenance and data collection were carried out monthly throughout the year. Even during the winter period, there were no failures in station maintenance and data collection. In this regard, it can be stated that seismic and infrasound monitoring is a reliable, stable, year-round, and all-weather type of monitoring for glacial process dynamics.

Figure 6 shows a view of the Shynybek station and a view from the station to Khan Tengri peak.

In 2025, data from the Merzbacher permanent station [

6,

7], installed in 2009 near Merzbacher Lake at the junction of the North and South Engilchek glaciers at an altitude of 3304 m above sea level, was added to the network data of three field stations in the near zone. The seismic station is only one element of the comprehensive high-mountain geoscience station of Gottfried Merzbacher, established by the Central-Asian Institute for Applied Geosciences (CAIAG) in collaboration with the German Helmholtz Center for Geosciences (GFZ), Potsdam.

Figure 7 shows a view of the Gottfried Merzbacher station. The station is located in close proximity to the glacier. It is a three-component seismic station Merzbacher (MRZ1), equipped with STS-2 broadband seismometers and digitizer EarthData PS6-24 installed in a 2 m-deep bunker. The sampling frequency is 20 samples per second. For reference: at the base of the Gottfried Merzbacher geoscience station, the CAIAG, together with the GFZ, carried out the work on sounding and seismic and glacial monitoring of the Engilchek glacier in the upper reaches of the Sary-Jaz River Basin. Airborne radar measurements have determined that the thickness of the Engilchek glacier in the area of Merzbacher Lake is 375 m. In total, the thickness of the glacier mass varies in this area from 250 m to 350 m. The Engilchek glacier has a layered structure: the upper layer is 44–66 m thick, the middle layer is 25–60 m thick, and the lower layer is 60–250 m thick [

8]. According to radio probe measurements, the thickness of the South Engilchek glacier varies between 350 and 400 m [

8].

According to Ref. [

7], “the data from the Merzbacher stations are freely available for use in environmental research and the provision of public information services, such as hydrometeorological services, as well as to support information-based decision-making, particularly in the areas of water and land resource management and climate change adaptation.” Files from the station are transmitted directly to the open-access Sensor Data Storage System (SDSS) developed and hosted by the CAIAG in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, and thus become immediately available to the public. Based on the existing memorandum between our organization and CAIAG, while carrying out work on the Targeted Funding Program related to the study of the climate impact on glacial processes, we were given access to the server with data from the Merzbacher station [

7].

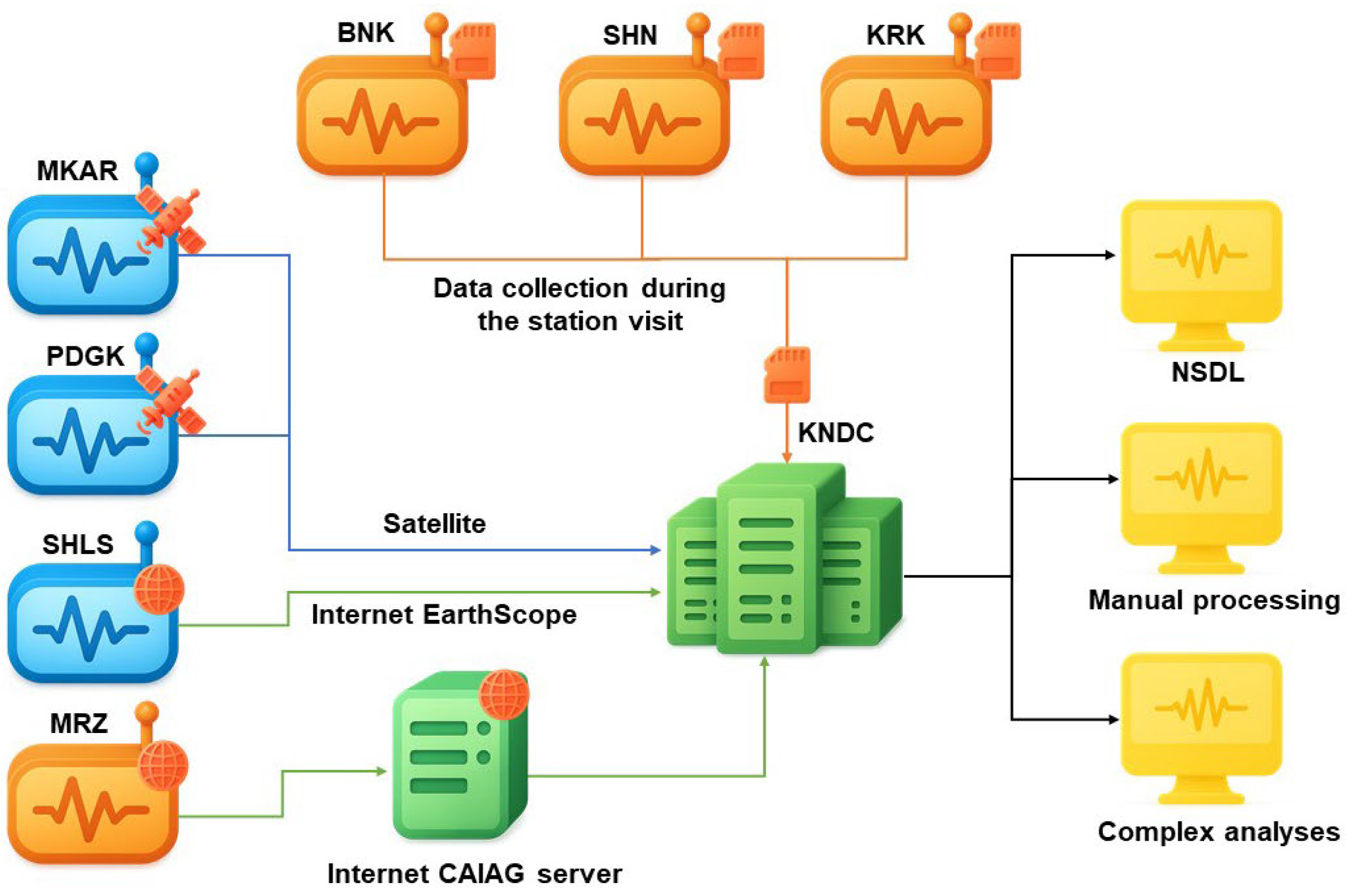

The MRZ1 seismic station data was included in the common database and connected to joint processing with data from three field stations of the IGR NNC RK and two permanent stations in this area—Podgornoye and Shalkode. Thus, the monitoring network in the zone close to the glaciers included six seismological stations. Additionally, remote data from the Makanchi seismic array, located more than 500 km from the glaciers, was used for analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Seismic Network Sensitivity for Observing Glacial Earthquakes and Factors Affecting Variations

When all stations were put into operation, the capability of the network to record glacial seismic events was studied, the predicted representative energy levels of recorded events were calculated, and variations of the monitoring sensitivity of stations were assessed. A similar analysis was conducted separately for seismic and infrasound stations.

Glacial processes was analyzed using data from following seismic stations: three field stations of the NNC RK (

Table 1)—permanent stations Pogronoye (PDGK) of the KZ NNC RK network and Shalkode (SHLS) of the QZ network (SNECCA Project, the operator is NRCSOR) [

9]—and one permanent station located directly at the glacial zone, Merzbacher of CAIAG [

6,

7]. Data from the entire seismic network is transmitted to the KNDC in Almaty via various channels (satellite, internet, delivered by engineers) and converted into a single database for processing (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9).

Figure 9 shows a chart of data acquisition process in KNDC, Almaty.

The values of approximate distance to the glacial event concentration zones are shown in

Table 2.

Seismic data processing was performed in automatic and manual modes. The NSDL automatic system for detection and location of seismic events was used [

10]. The NSDL system can be divided into two large functional groups. The first includes a detector and locator of regional seismic events for individual stations and some additional utilities, allows for viewing data from individual seismic stations, finds seismic events in them, preliminarily locates them, saves records of these events in separate files, and saves event parameters in bulletins and a database. The second part of the system is the associator. The associator summarizes data from several seismic stations for a single event, locates the detected events more accurately, rejects false detector triggers where possible, and saves the results in the form of a database and a bulletin [

10].

For manual processing, the Antelope 4.3 (BRTT) software package was used. According to the results of manual location, the accuracy of epicenter determination is 0.5–1 km, and according to the automatic location, it is 0.5–4 km. The accuracy of magnitude calculation is within 0.2 units.

Mpv magnitude and energy class K [

11,

12] are used for magnitude and energy characterization of events. The mpv magnitude scale is analogous to the mb magnitude. For its calculation, the records by SKM-type instruments (vertical component) for longitudinal waves and a regional calibration curve for the Tien Shan and Dzhungaria regions are used. This scale is very convenient for parameterizing small and moderate earthquakes in the studied area of the Tien Shan. The mpv magnitude classification has been used in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan along with the K energy class for almost 40 years. Currently, its application is necessary to maintain the continuity and uniformity of the Central Asian earthquake catalogs.

Since its introduction in 1979, the moment magnitude Mw has been used for small, moderate, and large earthquakes. Initially, Mw was mainly calculated for large earthquakes with magnitudes greater than about 4.5 due to data and methodological limitations. In this work, we investigate small seismic events. Mw for small and moderate earthquakes can be estimated using different approaches; for example, coda calibration technology (CCT) [

13,

14]. At our center, such calculations have been performed for earthquakes in the Northern and Southern Tien Shan, yielding several conversion ratios of Mw (CCT) with respect to standard magnitude measures such as mb, mpv, and K [

15]. Within the International Science and Technology Center (ISTC) Project “Central Asia Seismic Hazard Assessment and Bulletin Unification” (CASHA-BU, 2021–2023) [

15], conversion ratios linking the values of mpv and K with Mw, calculated using the CCT technique [

13,

14], were obtained. The following conversion ratios have been developed for transition to a single characteristic of event magnitude—Mw:

Some recent studies, for example, Ref. [

16], describe correcting Mw values by calculating Mwg values for earthquakes with a magnitude of 3.5 or higher. To convert mpv magnitude values to Mw values, one can use the formulas from Ref. [

16].

Using the mb-to-mpv ratios and formulas from Ref. [

16], we obtained a relationship between Mwg and mpv and estimated the magnitude thresholds of seismic events recorded by the network of field stations in Mwg units. The results of the calculations for both mpv and Mwg magnitudes are given in

Table 3, and by energy class in

Table 4.

Table 3 shows that individual stations are capable of recording seismic events with magnitudes starting from 1.5 (Mwg) at night and 1.6 (Mwg) during the day without gaps. The representative magnitude level across the network, if at least three stations are given for locating a single event, is Mwg = 1.9–2.2.

3.2. Seismic Noise and Its Variation

Seismic noise was analyzed for all six stations installed in the near zone. The calculation method used is described in Ref. [

17]. The analysis was performed in the following steps:

- -

The selection of recording segments for the same periods of time for day (6–7 a.m. GMT) and night (4–5 p.m. GMT). The segments were 10 min long and records without events were selected, with 10 segments separately for day and night.

- -

The calculation of the spectral characteristics of noise for each station, for each component, separately for daytime and nighttime periods.

- -

The calculation of average (median) spectral curves (noise models) for each station and each component for day and night.

- -

The comparison of results with Peterson’s global noise models [

18] and between data from all stations in the near zone.

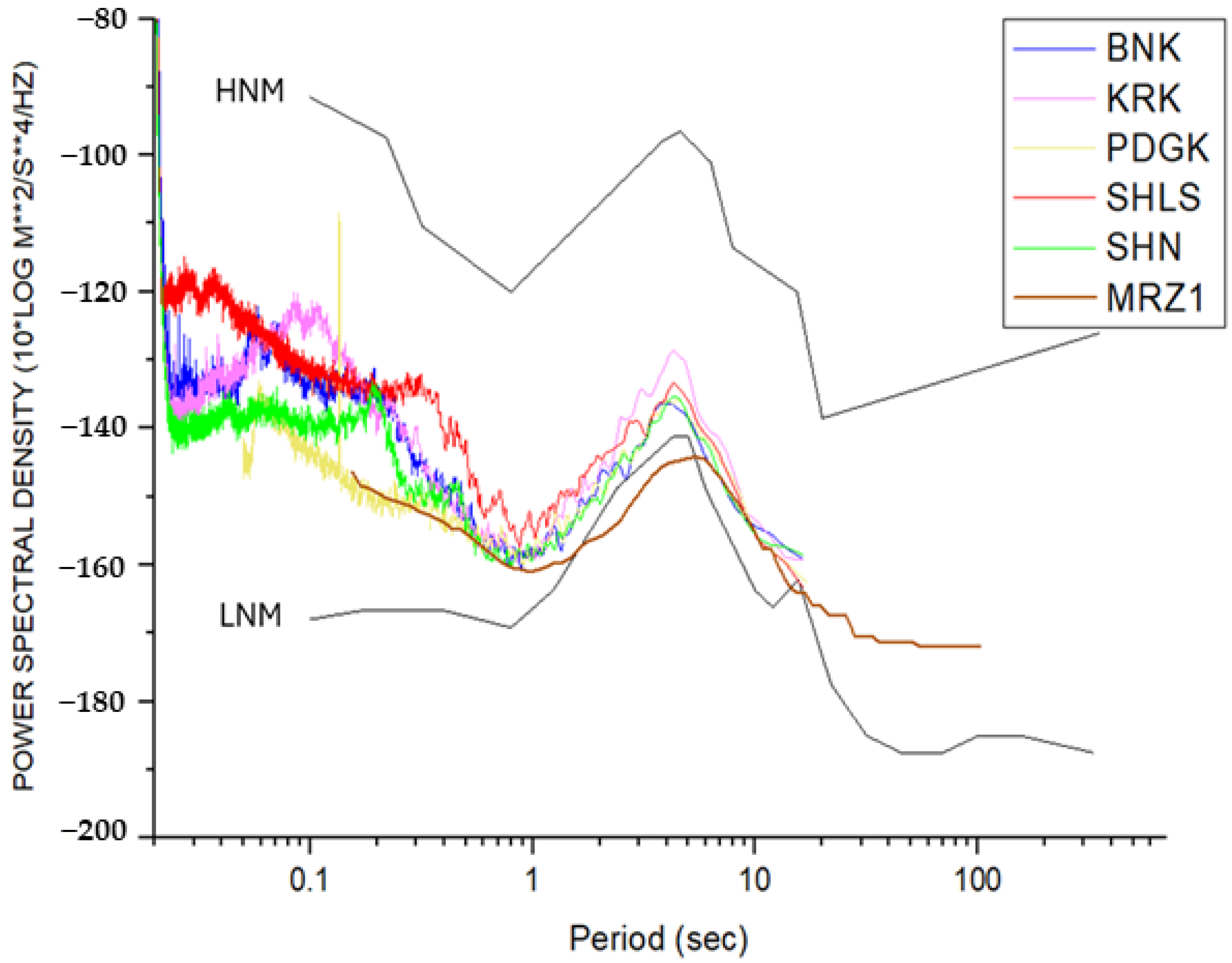

Below are summary graphs of the spectral power density of seismic noise for all stations for nighttime (

Figure 10). The black lines show the standard high-level and low-level seismic noise curves (High Noise Model and Low Noise Model) according to Peterson [

18], which allow for the noise level to be assessed relative to global models.

A comparison of daytime and night− time noise levels shows a clear pattern in noise variations throughout the day. The daytime noise level is higher than the nighttime level at frequencies above 5 Hz at all stations except the Merzbacher station. The Merzbacher station also has the lowest noise level (

Figure 11). However, a slight increase in daytime noise is noticeable at this station at frequencies close to 1 Hz. A low noise level is also observed at the Podgornoye station. The equipment at these two permanent stations was installed in bunkers on a rock foundation. However, the equipment at the field stations was installed in seismic vaults of 40–50 cm in depth.

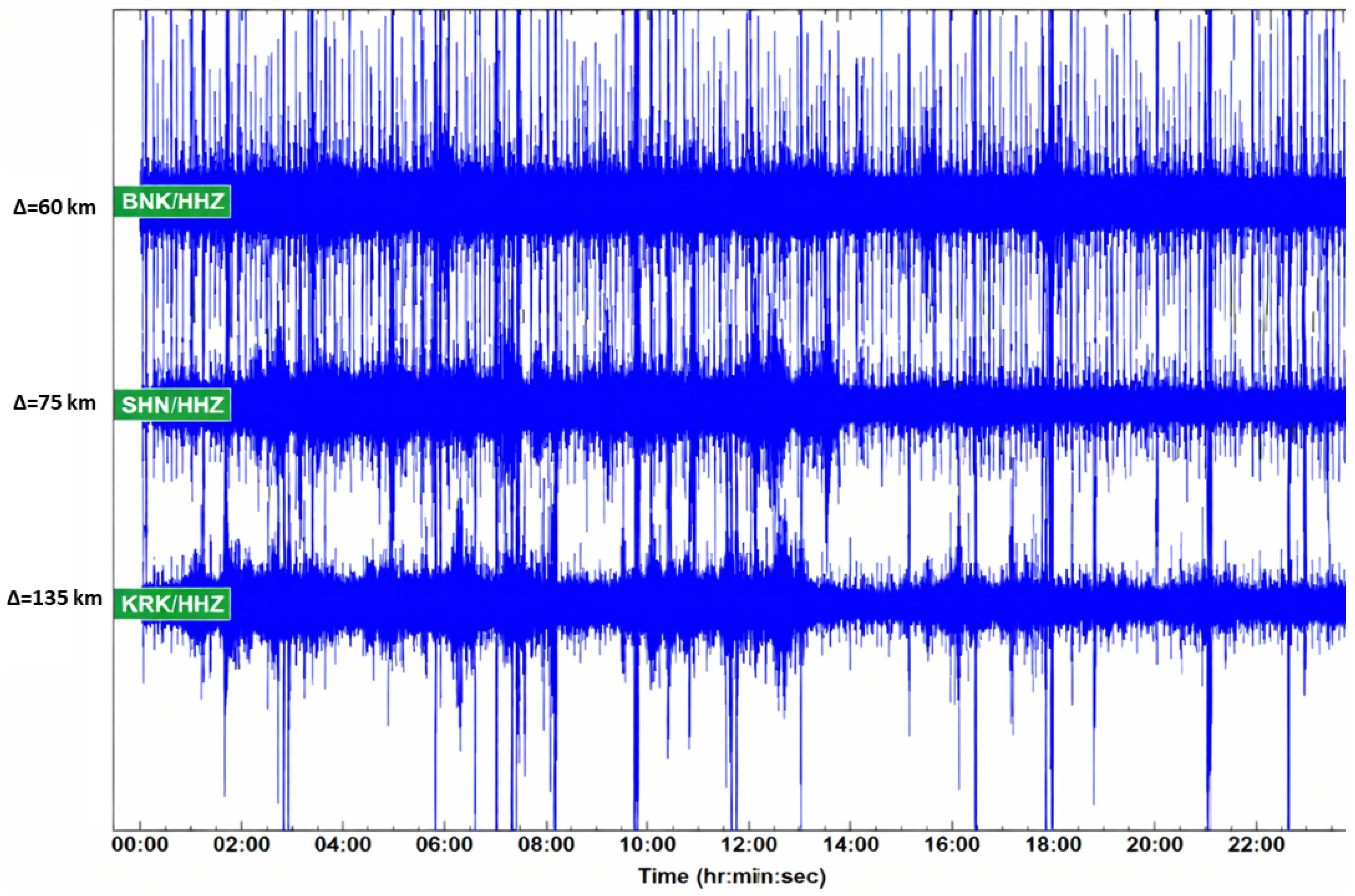

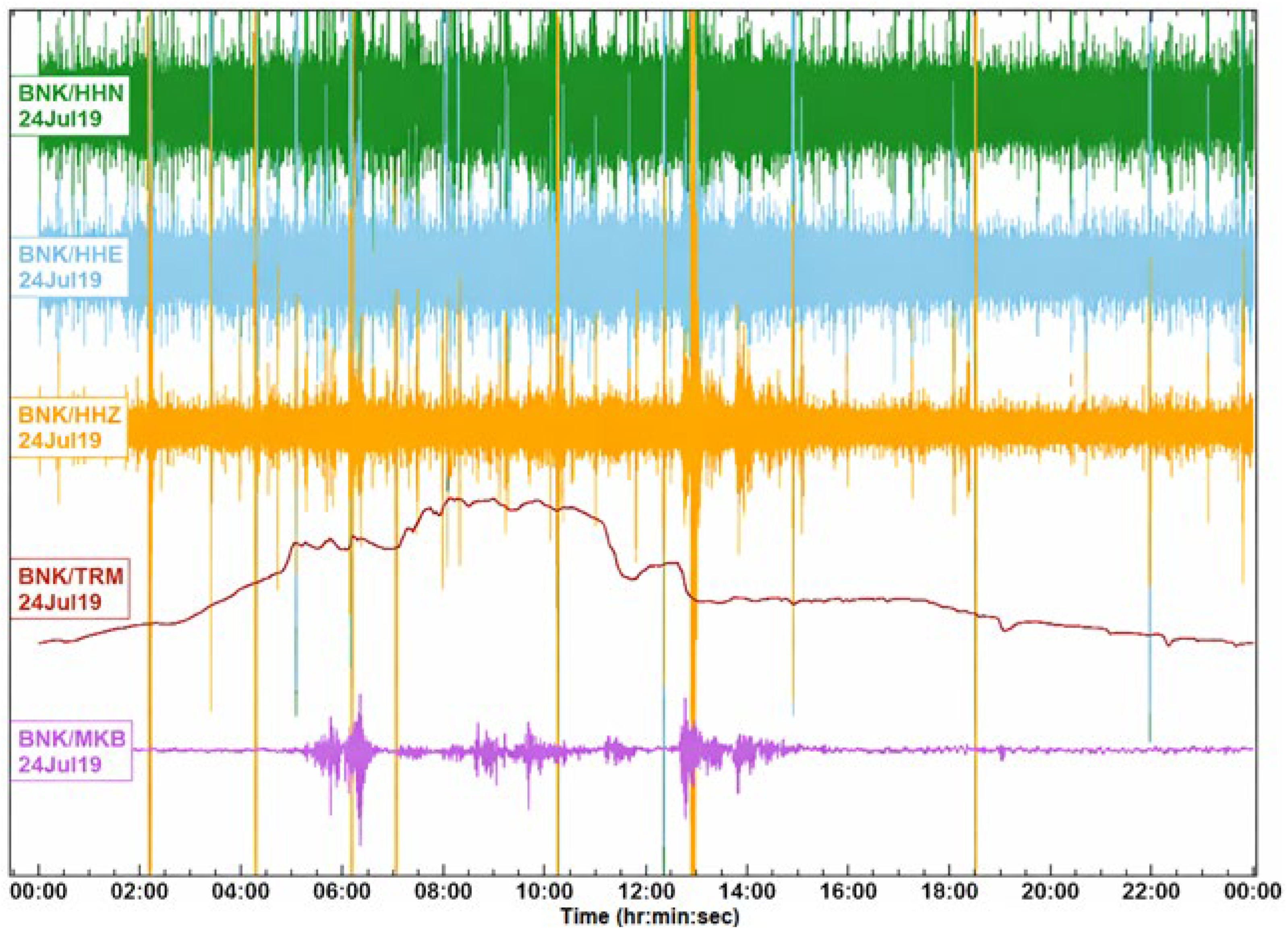

Figure 12 shows seismograms from field stations for one day, Z components. The station traces in the figure are arranged from top to bottom according to their distance from the glacial zone (60 km Bayankol, 75 km Shynybek, 135 km Karkara).

The analysis of diurnal seismic records from three field stations clearly shows, even without any processing, a difference in seismic noise levels between day and night hours. At approximately 13–14 h GMT (18–19 h local time), the noise level changes significantly: it becomes lower (the width of the dark part of the vibration trace narrows). This effect is more pronounced at the Shynybek and Karkara stations and less at the Bayankol station. The vertical lines on all traces are glacial seismic events, the exact number of which cannot be calculated. The number of seismic events decreases with distance from the glaciers.

Figure 12 shows similar diurnal seismic oscillations from the Merzbacher station. The almost complete absence of visible daily variations in seismic noise is noteworthy. The width of the “dark” band remains almost unchanged throughout the day.

The possible reason for this is the significantly different locations of the stations and different conditions of the equipment installation. Seismic noise levels at the field stations are affected by increased general noise from transport, the operation of various devices, and agricultural activity in villages during daylight hours, which are completely absent at the altitude of the Merzbacher station (3304 m). In addition, at the Merzbacher station, the equipment is installed in a 2 m bunker, while at the other stations, the equipment is installed in seismic vaults of 40–50 cm depth. This excludes the influence of wind interference on the seismic noise level.

The data analysis also showed a noticeable increase in the number of glacial events after 15:00 GMT (evening and night, local time). This phenomenon is also confirmed by the results of all network data processing: the diurnal number of glacial earthquakes clearly depends on temperature change.

In cases where the actual physical characteristics of the oscillations are known from seismic noise recordings, the minimum expected magnitudes and energy classes of glacial earthquakes can be estimated upon detection. The following well–founded assumptions were used. It was assumed that the amplitude of the signal in P–waves should exceed the amplitude of seismic noise by three times, and the amplitude of S–waves should be approximately twice the amplitude of P–waves.

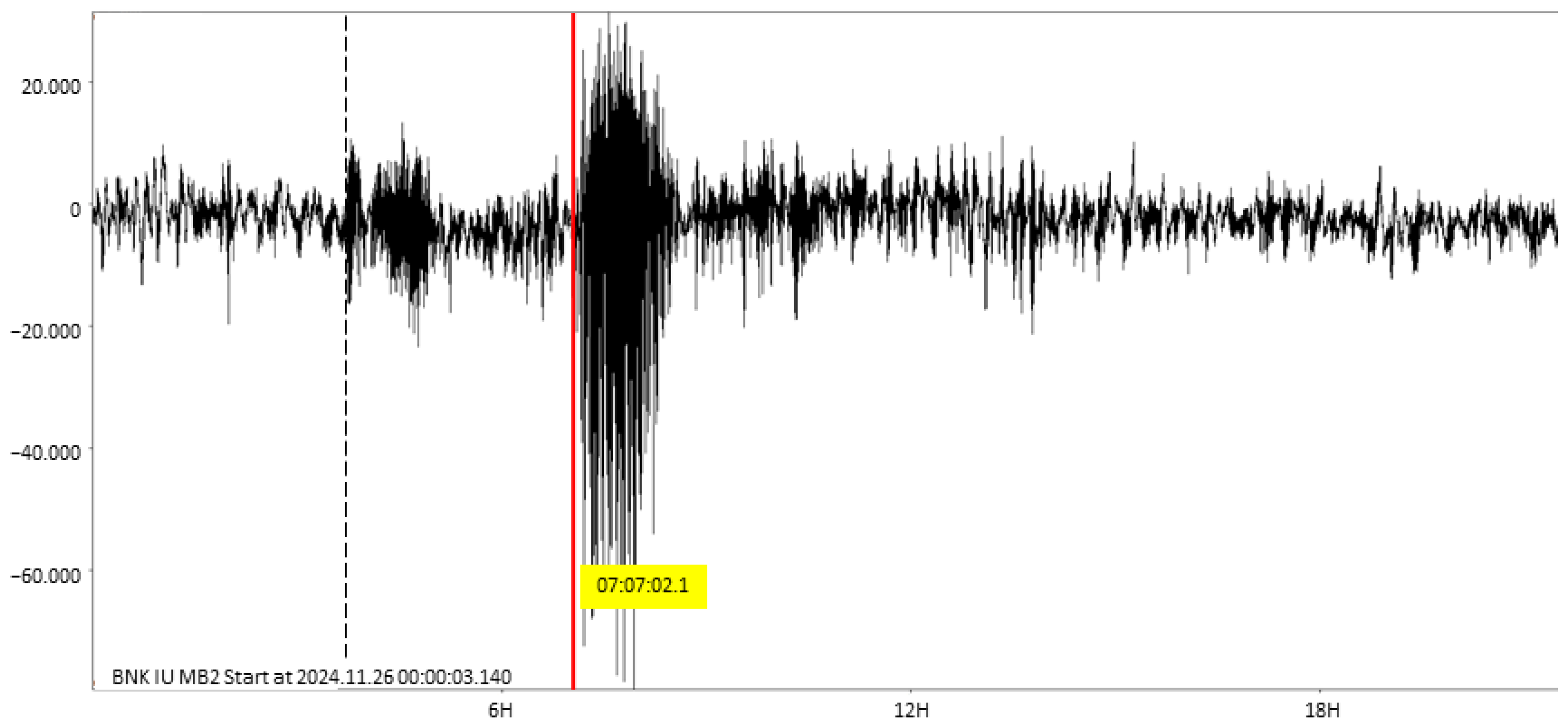

Figure 13 shows the waveforms for all stations in the near zone. However, all stations of the IGR NNC RK network record velocity, while the Merzbacher CAIES station records ground displacement.

Formulas for estimating the regional magnitude mpv [

11] and energy class K [

12] for Tien Shan earthquakes were used for the calculations. Since significant variations in oscillations during the day have been established, the calculations were performed for day and night. The night records show the smaller earthquakes clearer than the day–time records due to the noise variations.

The energy class is calculated using the formula K = 1.8 ⋅ log10 (Ap + As) + Ω(Δ,km), where Ap and As are the maximum amplitudes of longitudinal and transverse seismic waves measured in microns on the SKM channel, and Ω is a calibration function describing the attenuation of seismic waves, depending on the epicentral distance. Magnitude mpv = log10(Ap/T) + σ(Δ,km). Ap and T are the amplitude and corresponding period in the displacements of the longitudinal wave of ground vibrations, and σ(Δ,km) is the calibration function for Ap/T describing the attenuation of the vibration velocity depending on the epicentral distances. Note that for the Merzbacher station, it is not necessary to convert from velocities to ground displacements when calculating using these formulas since we had displacement records as the input.

The obtained results of the predicted sensitivity of the established monitoring network are shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

The analysis of seismic noise records from all stations installed in the near zone allow us to assume that the network is capable of detecting and locating glacial events of mpv ~2–2.5, Mwg ~1.9–2.2, and with an energy class of 5–6.

3.3. Analysis of Meteorological, Infrasound, and Seismic Data

For meteorological observations at the Bayankol (BNK), Karkara (KRK), and Shynybek (SHN) stations, a compact “Gill Maximet GMX 500” weather station able to record five basic parameters was used:

Wind speed (LWS), measurement unit—m/s.

Wind direction (LWD), measurement unit—° northward.

Temperature (LKO), measurement unit—°C.

Relative humidity (LIO), measurement unit—%.

Atmospheric pressure (LDO), measurement unit—kPa.

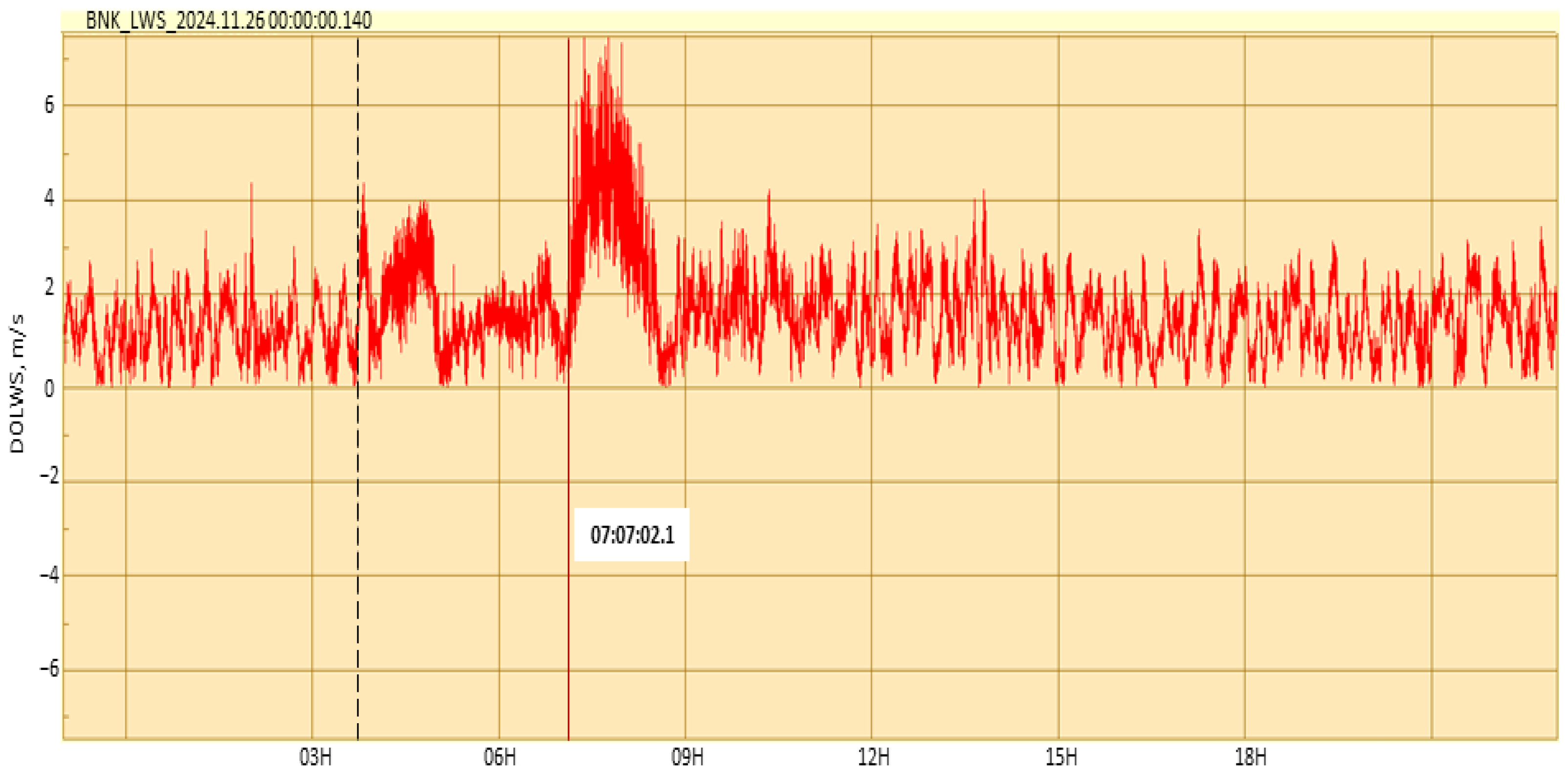

Based on meteorological data, wind increases and daily and seasonal changes in wind speed were studied for each station. The results of the meteorological data analysis are shown in the example of the Bayankol (BNK) station. An examination of the combined graphs of wind direction and speed allowed us to determine regular periodic changes in wind direction, characterized by relative stability in the evening and nighttime periods. In most cases, changes in wind direction coincide with an increase in wind speed. The prevailing wind speed ranges from 0.3 to 1.5 m/s, with an increase to 9.6 m/s during changes in direction. This analysis was performed every ten days during the entire observation period.

Then, the wind increases diagrams were constructed and analyzed for the Bayankol (BNK) station. The diagrams are divided into 16 sectors, each covering a direction equal to 22.5°. The prevailing wind direction, for example, in December 2024, is 180–202.5°, followed in intensity by 202.5–225° and 157.5–180° (

Figure 14). There is almost no wind from the direction 315–45° to the area of glacial seismicity.

Figure 14 schematically shows the wind direction relative to the station location. Long bold arrows indicate the direction during the night breeze, long thin arrows indicate the wind direction during the daytime breeze, and short thin arrows indicate a light wind during the change of main directions. The background of the figure is a satellite image.

The figure shows that the prevailing wind direction coincides with the direction of the Akkol Gorge, where the station is located. The azimuth of the Akkol Gorge is 195°, which is consistent with the wind increase diagram. The azimuth of the Bayankol Gorge that adjoins the Akkol Gorge is 120° at the point of junction, with a further change in azimuth to 355° in a northerly direction and subsequent exit into the foothill valley (not all of the area is shown in the figure).

Based on the results of the wind regime analysis at the station’s site over the year, the following can be stated:

- -

In general, the wind regime is relatively stable and predictable, except for periods when there are sudden changes in weather conditions (cyclones, anticyclones, etc.).

- -

The main direction of air mass movement in the surface layer during night and day breezes coincides with the direction of the gorge.

- -

Wind speed is mainly within the range of 2–4 m/s, increasing to 8–10 m/s during the transition from night breeze to day breezes, with gusts of up to 16 m/s.

- -

The daily cycle is roughly as follows: from 4 p.m. to 7:30 a.m. local time the next day (evening, night, and early morning), air masses move down along the Akkol Gorge, exiting into the Bayankol Gorge and further into the foothill valley. These are descending flows of air cooled overnight. Then, from 7:30 to 10:00, there is a temporary calm during which the wind direction changes. From 10:00 to 14:00, the air warmed in the valley begins to rise into the mountains, the wind speed increases, and the direction changes to almost the opposite. From 14:00 to 16:00, calm returns, the wind changes speed and direction, and the cycle repeats.

- -

During sudden weather changes (cyclone, anticyclone), the direction and speed of the wind change chaotically.

- -

There is practically no wind from the northwest and north directions, as there is a dead-end gorge in this direction that only leads to the Akkol Gorge.

A comparison of wind diagrams from all field stations shows that the main direction of surface winds at the Karkara and Bayankol stations is almost perpendicular to the direction of the research object, which makes it unlikely that infrasound signals generated by the glaciers of the central Tien Shan Mountains will be detected. The main wind direction at the Shynybek station not only corresponds well with the direction of the glaciers but also covers almost the entire area of the high-mountain Tien Shan. Thus, most probably, the Shynybek station can detect infrasound signals from glacial phenomena not only reflected from the stratosphere but also directly from glaciers, compared to the Karkara and Bayankol stations.

An analysis of the stations’ infrasound records revealed very intense fluctuations throughout each day. A detailed examination of combined infrasound and meteorological data revealed patterns in the periodicity of acoustic noise.

Figure 15 shows a three-day record of microbarometer signals (Bayankol station). The recording began at 00:00 on 30 May 2024 and ended at 23:59 on 1 June 2024 (GMT). The upper trace is the microbarometer record, and the lower trace is the recording from the temperature sensor installed at the same site.

Figure 15 shows that the onset of intense acoustic noise clearly correlates with the air temperature increase at the microbarometer installation site. The time from the temperature increase beginning to the appearance of intense acoustic noise is about two and a half to three hours. The duration of intense acoustic noise is, on average, about nine and a half to eleven hours per day. The average background noise level at night is about 18 mV, and during the day, it is 570 mV.

This pattern is observed daily throughout the entire observation period, significantly complicating the detection of infrasound events during the daytime against the background of interference. The time of the temperature increase beginning, the strengthening in wind speed, and the time of strong infrasound interference and its duration on the microbarometer records are completely synchronized. Thus, it can be concluded that the increase in the acoustic interference intensity on the microbarometer records is a consequence of meteorological parameter changes at the equipment installation site.

Figure 16 and

Figure 17 show that the time of wind speed increase and the time of the beginning and duration of intensive infrasound noise are completely synchronous in the microbarometer records.

Figure 18 shows a summary graph of temporal changes by a set of data from a multi-parameter system. Three components of seismic station records, temperature records, and infrasound station records are shown.

There is a correlation between the occurrence of infrasound and seismic noise and daily temperature changes. For infrasound vibrations, this correlation occurs due to the changes in wind parameters as a result of daily temperature increase; for seismic vibrations, the temperature increase after sunrise determines the overall level of cultural interference increase due to human activity at the station’s location area, increased traffic on the roads, the start of agricultural work in the fields, etc. The wind impact on the field stations’ equipment installed in seismic vaults also cannot be denied.

Based on the conducted analysis, an important methodological conclusion was made regarding the detectability of infrasound signals from glaciers: the most promising station for its detection is Shynybek, which is characterized by the wind direction directly from the zone of glacial earthquakes. The infrasound signals are better able to be searched outside the period of intense daytime noise associated with temperature and wind changes. This period can be predicted quite accurately.

As the number of the infrasound stations used (one and later two) did not allow for analyzing its data as an array and applying, for example, the PMCC technique [

19], the azimuth of the signal arrival, and the apparent velocity. All further processing of infrasound data was based on the association of infrasound signals with data from the seismic bulletin of glacial earthquakes. For further monitoring of glaciers, it is recommended to install an infrasound array consisting of at least three microbarometers and to apply infrasound wave path modeling to select the best site for infrasound recording.

During the glacial seismicity monitoring network operation, more than 4000 seismic events were recorded and processed at the data center. A seismic bulletin was compiled. A map of the located events epicenters is shown in

Figure 19. Within the area of the large-scale glaciers of the high-mountain Tien Shan that has linear dimensions of more than 200 km, a zone of high seismic activity with clear boundaries and structure is clearly distinguished. The events with the minimum magnitude were recorded by the Bayankol station: mpv = 0.9, Mwg = 0.7. Events with mpv = 2.0 and Mwg = 1.9 were detected and located without omission. The analysis of the identified patterns of glacial seismic events is beyond the scope of this paper.

—Recorder DR 4040, seismometer CMG 40T, accelerometer CMG 5T.

—Recorder DR 4040, seismometer CMG 40T, accelerometer CMG 5T.  —Electronic thermometer.

—Electronic thermometer.  —Microbarometer MB2005.

—Microbarometer MB2005.  —Microbarometer MB 3A.

—Microbarometer MB 3A.  —Weather station GMX 500.

—Weather station GMX 500.

—Recorder DR 4040, seismometer CMG 40T, accelerometer CMG 5T.

—Recorder DR 4040, seismometer CMG 40T, accelerometer CMG 5T.  —Electronic thermometer.

—Electronic thermometer.  —Microbarometer MB2005.

—Microbarometer MB2005.  —Microbarometer MB 3A.

—Microbarometer MB 3A.  —Weather station GMX 500.

—Weather station GMX 500.