Probabilistic Analysis of Rainfall-Induced Slope Stability Using KL Expansion and Polynomial Chaos Kriging Surrogate Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Stochastic Field Modeling Based on Karhunen–Loève Expansion

2.1.1. Mathematical Foundation and Theoretical Framework

2.1.2. Implementation Steps and Key Technologies

- 1.

- Preliminary Data Processing

- 2.

- Covariance Function Selection

- 3.

- Solving Eigenvalue Problems

- (1)

- Galerkin Method: Discretizes integral equations into matrix eigenvalue problems, suitable for irregular domains and complex covariance functions.

- (2)

- Wavelet-Galerkin Technique: Combines wavelet basis functions to improve computational efficiency, suitable for large-scale random fields.

- 4.

- Order Truncation Determination

- 5.

- Non-Gaussian Random Field Processing

2.2. Alternative Modeling Theory

2.2.1. Polynomial Chaos Expansion (PCE)

2.2.2. Kriging

2.2.3. Polynomial Chaos Kriging (PCK)

2.3. Control Equations of Rainfall Infiltration Model

2.3.1. Water Flow in Unsaturated Soil

2.3.2. Elastic–Plastic Deformation in Soil

2.3.3. Local Safety Factor Method

2.4. Calculation Procedure

3. Model Settings

4. Result Analysis

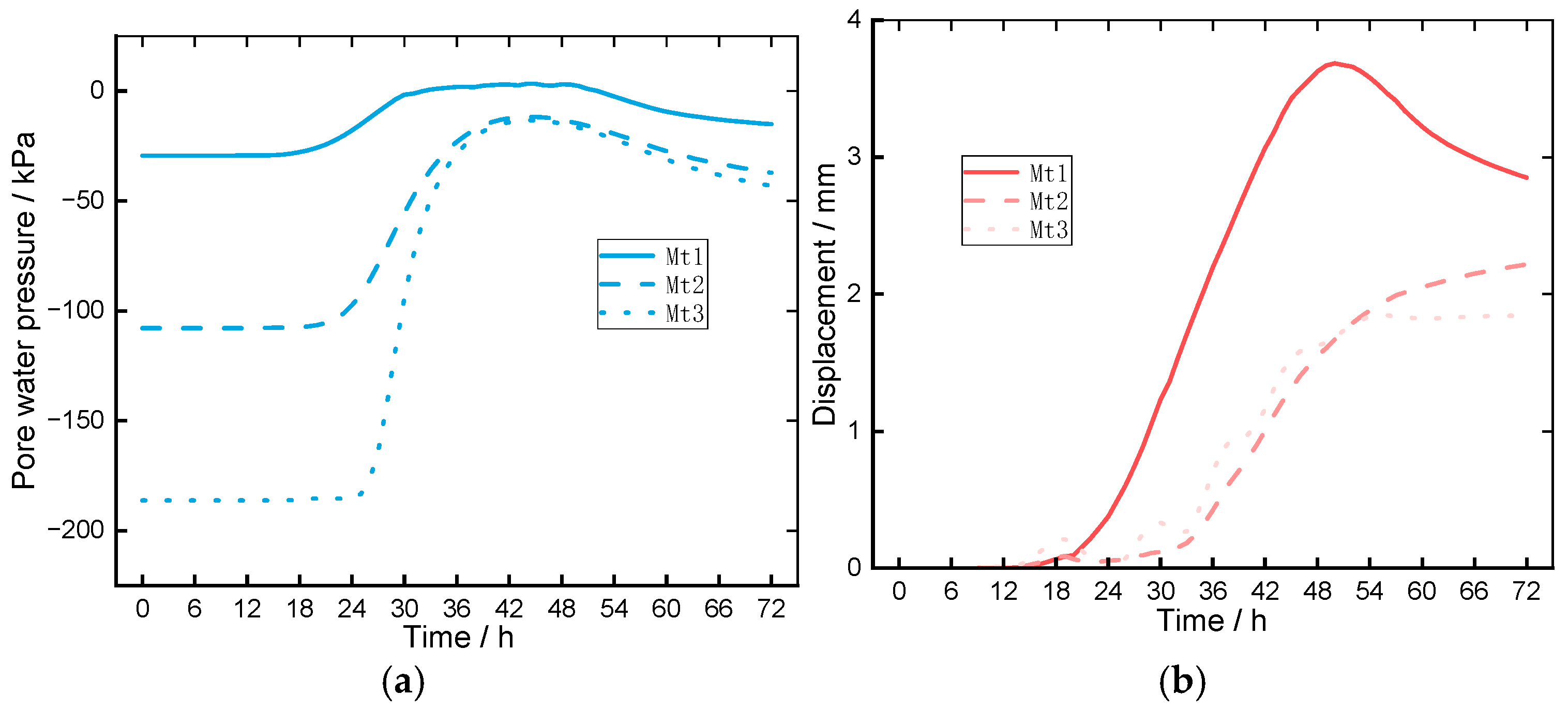

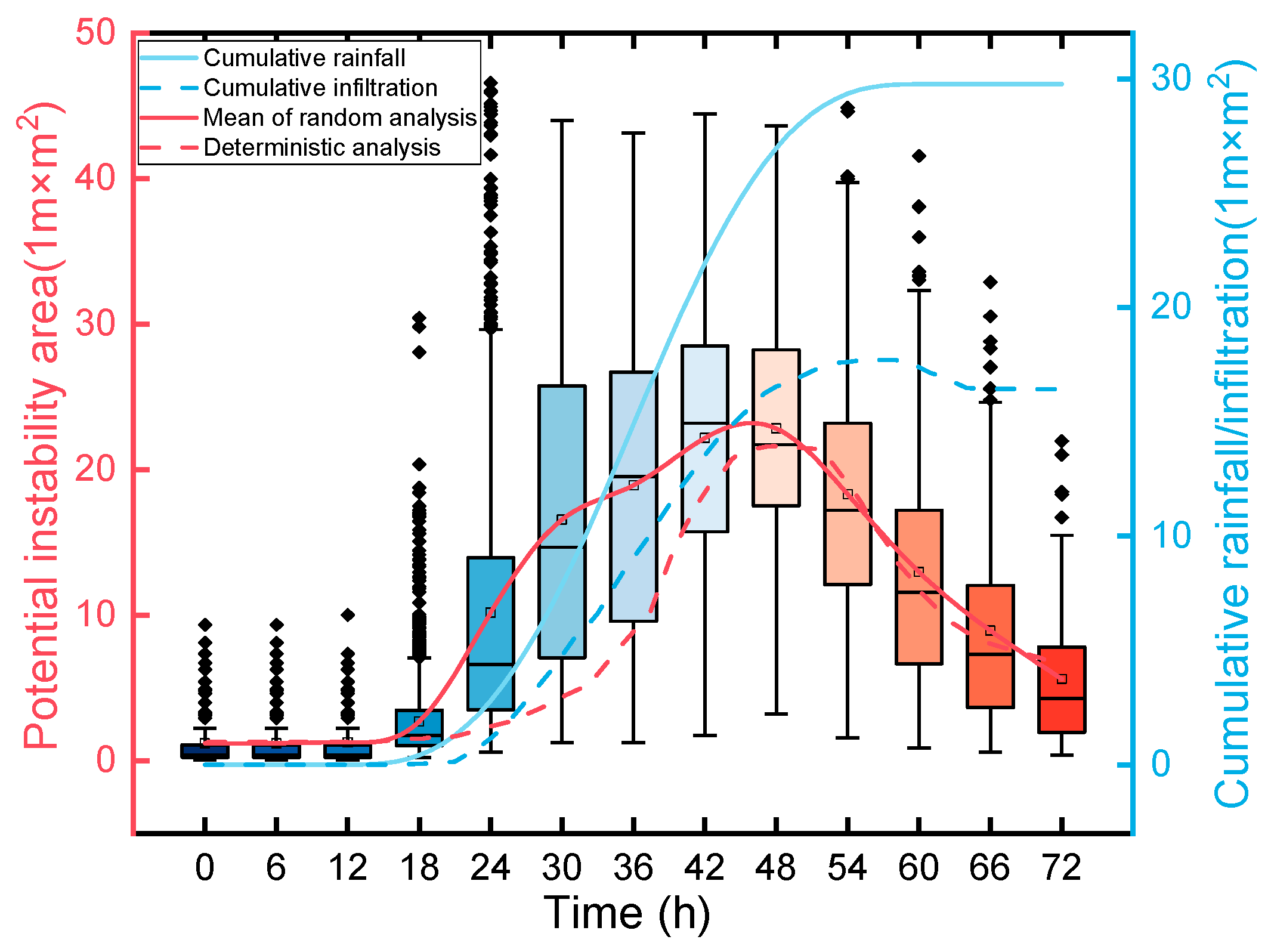

4.1. Definitive Analysis

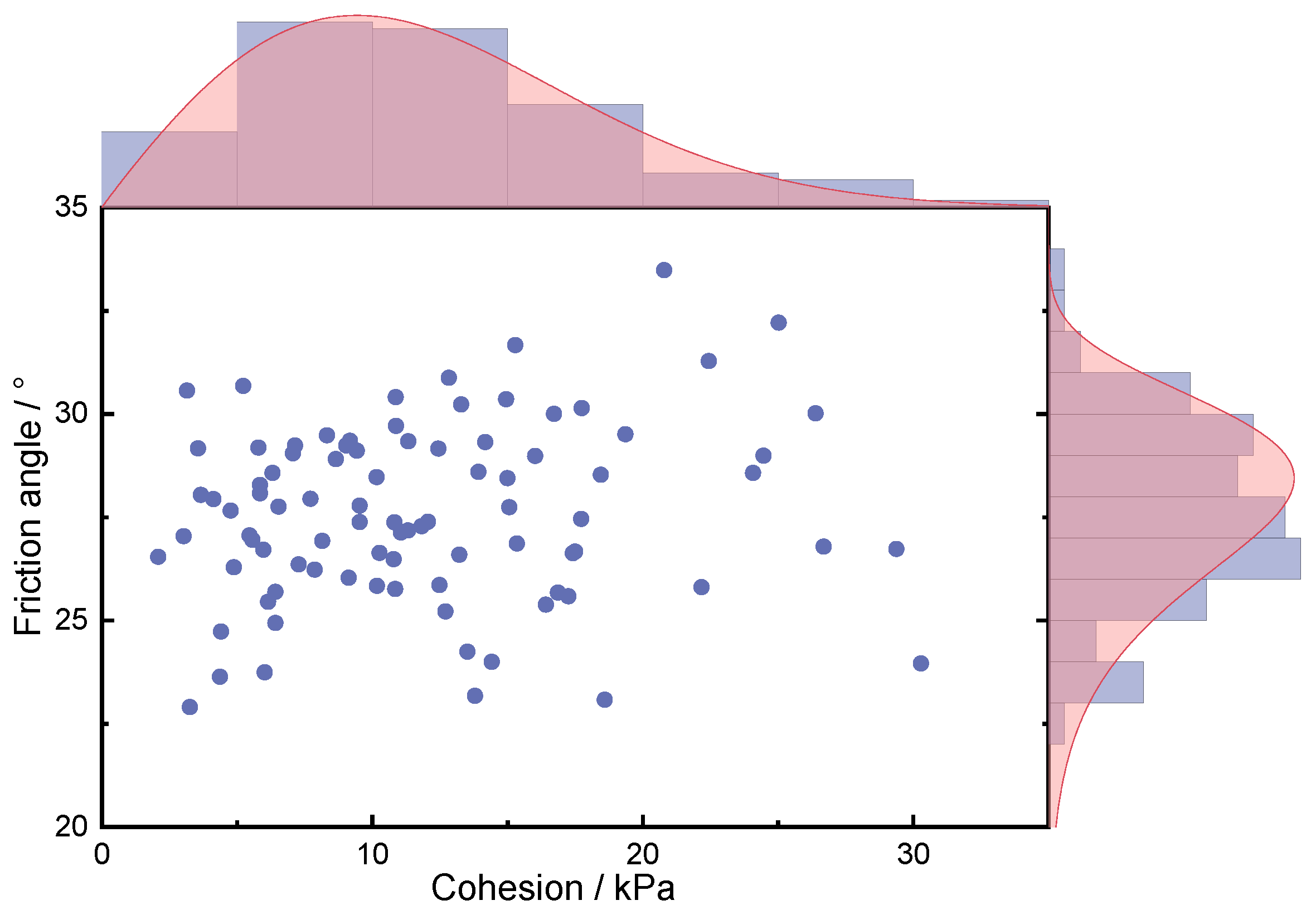

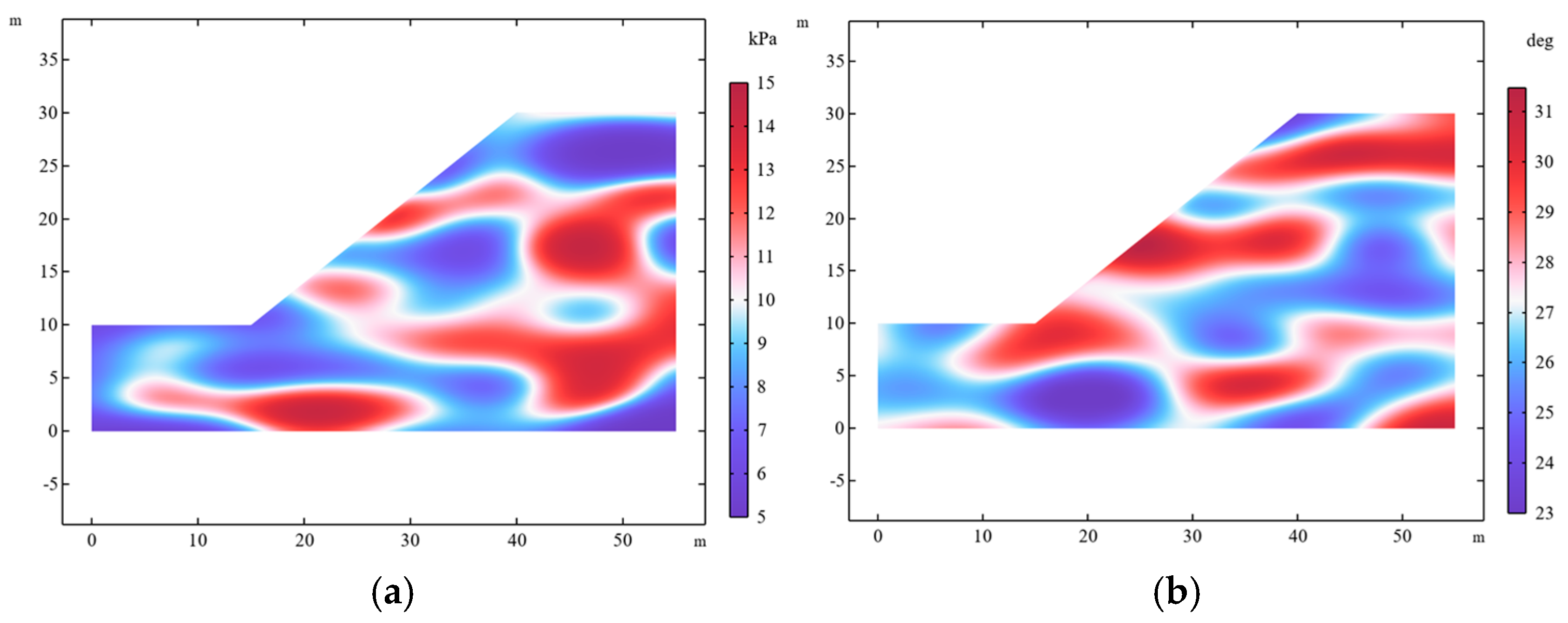

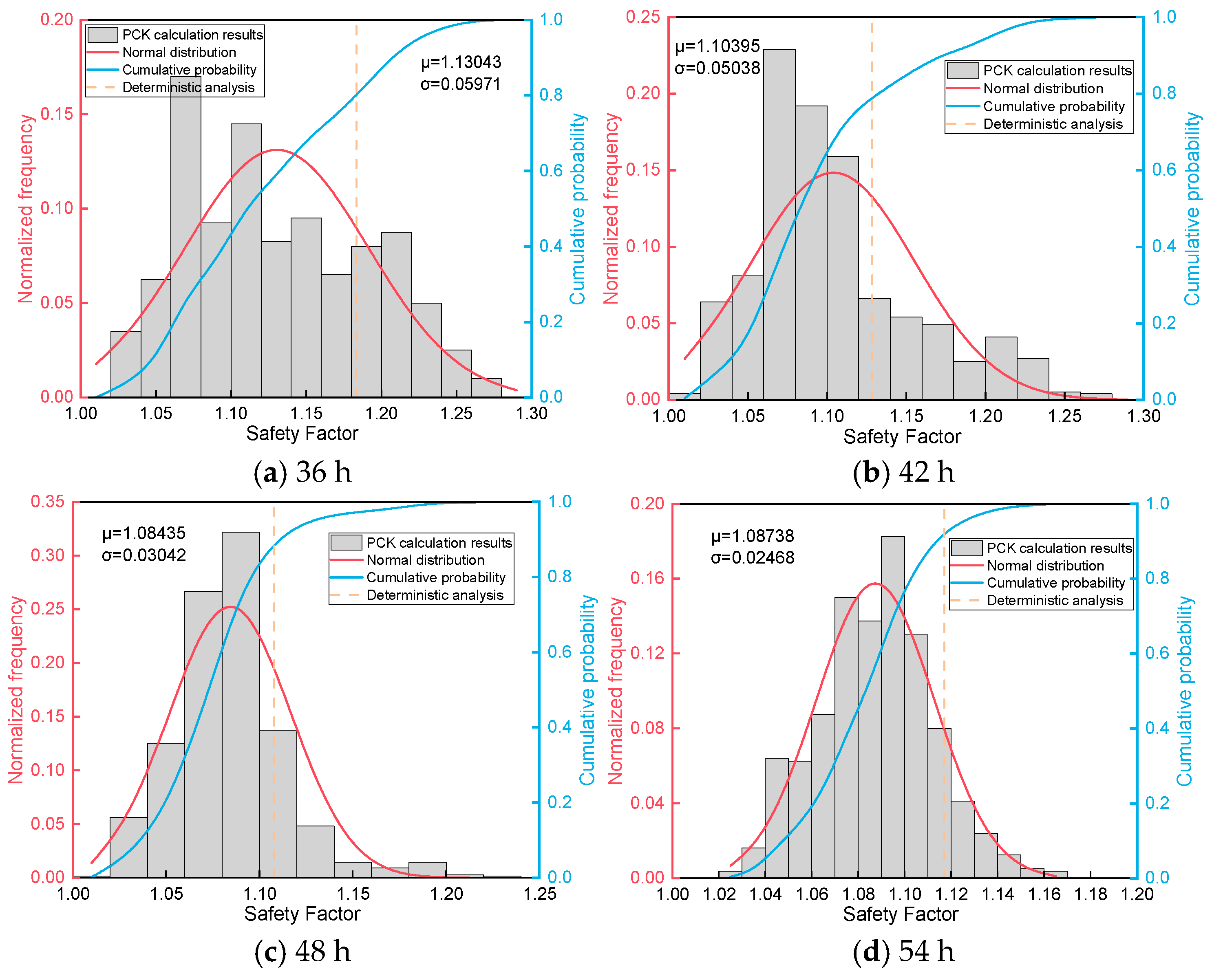

4.2. Uncertainty Analysis

5. Discussion

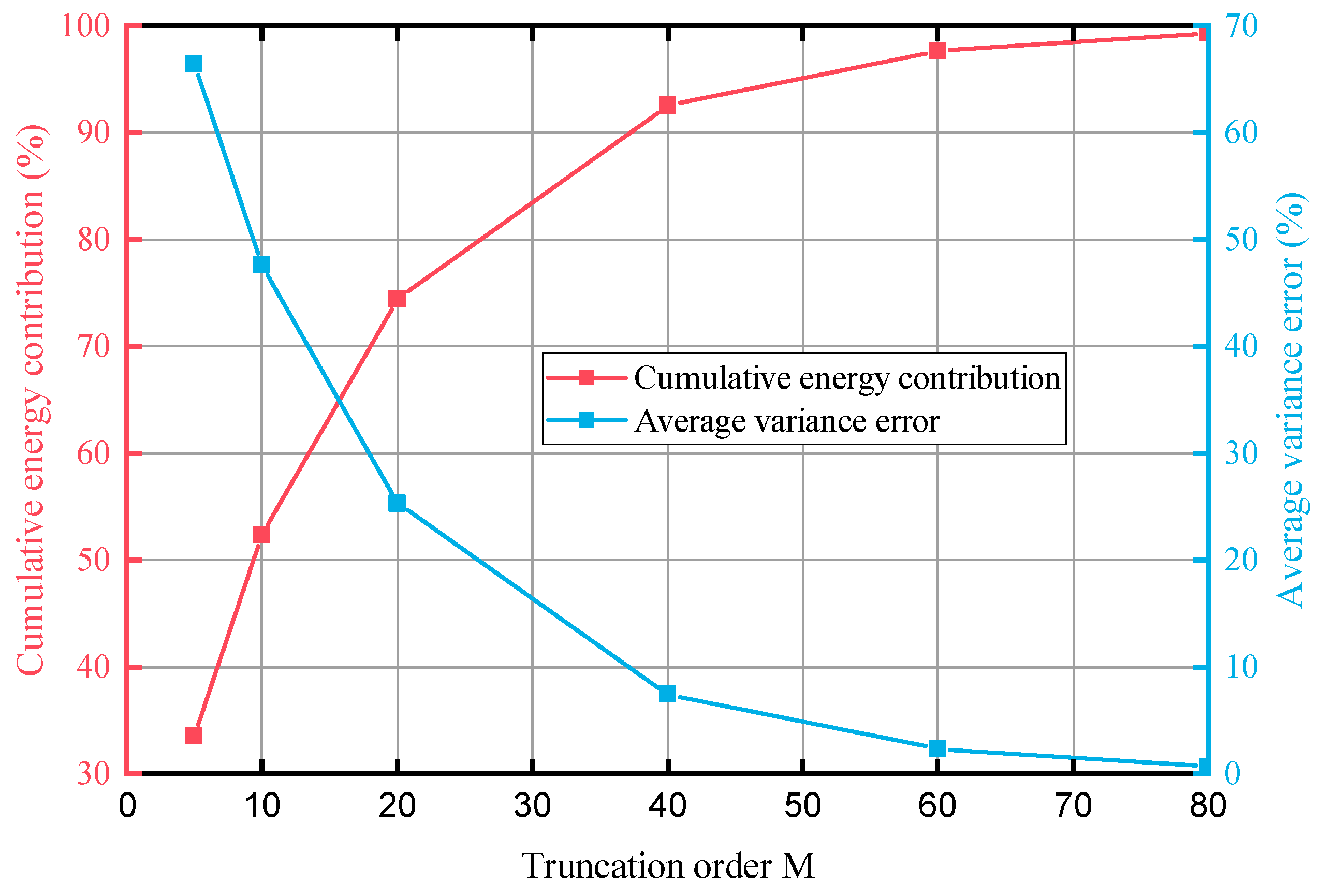

5.1. Sensitivity Analysis of KL Expansion Truncation Order

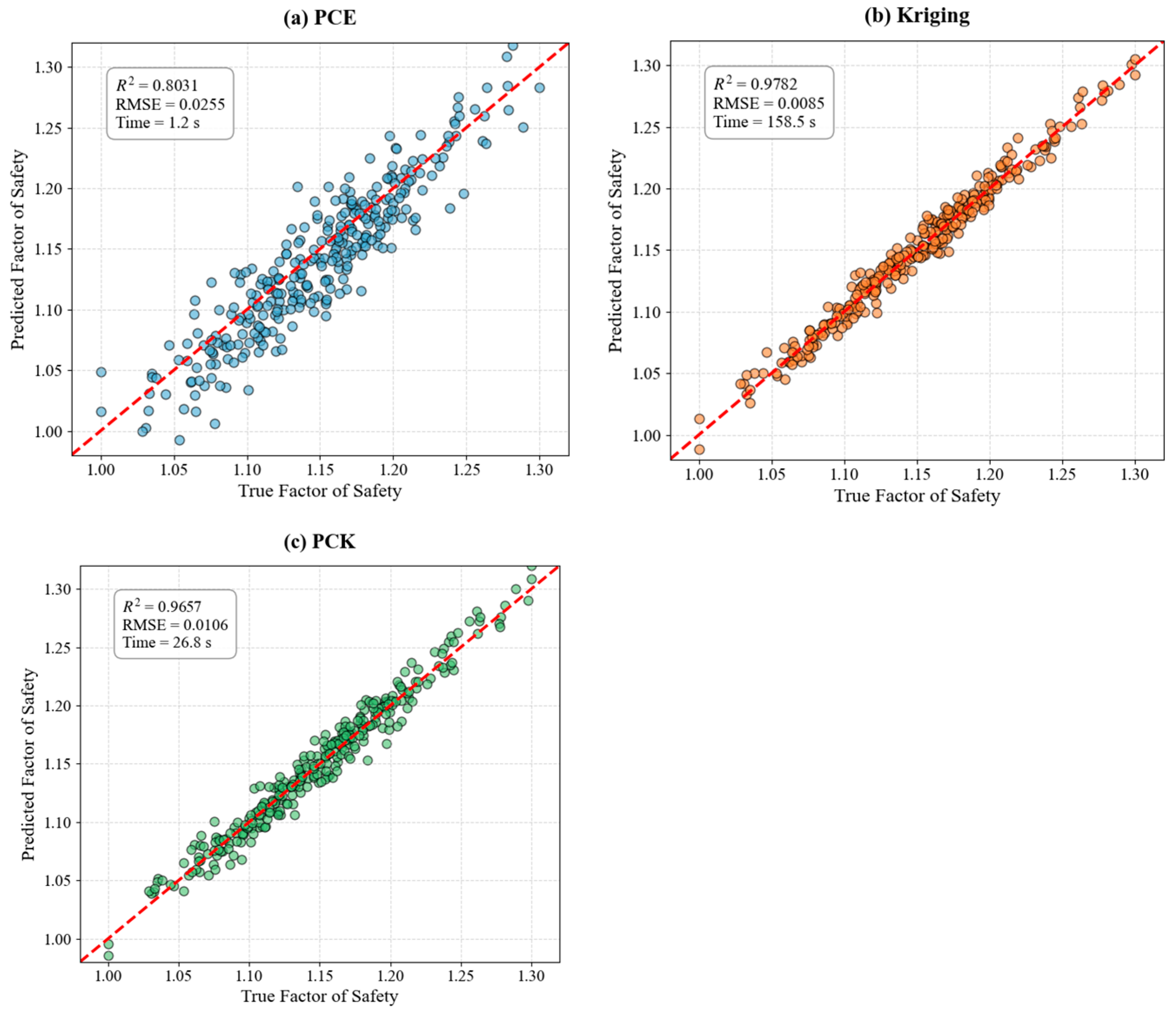

5.2. Comparison of Surrogate Model Performance

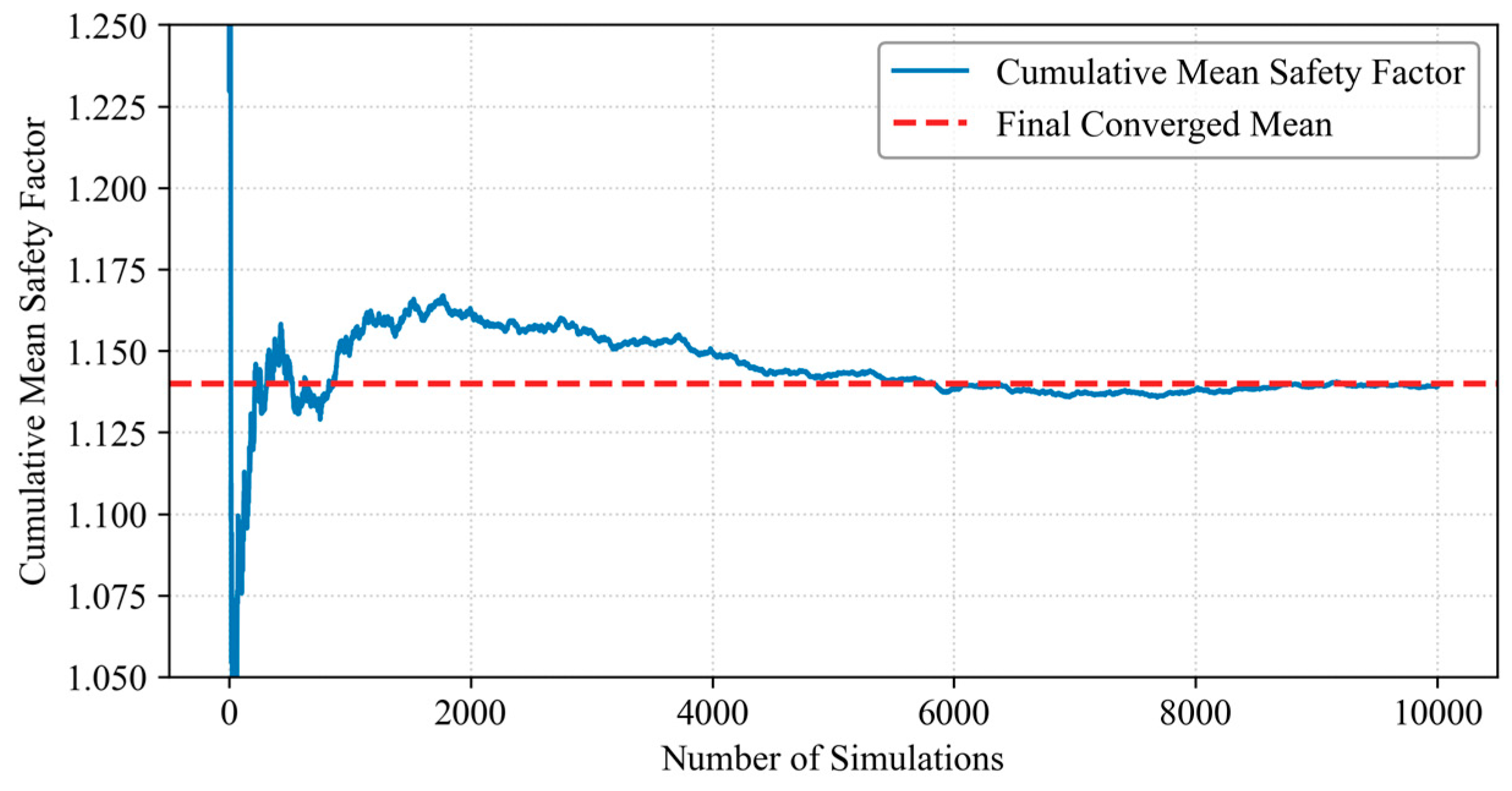

5.3. Monte Carlo Simulation Convergence

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gariano, L.S.; Guzzetti, F. Landslides in a changing climate. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2016, 162, 227–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harianto, R.; Alfrendo, S.; Choon, E.L. Effects of Rainfall Characteristics on the Stability of Tropical Residual Soil Slope. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences, Lyon, France, 17–21 October 2016; p. 915004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China. 2022 China Natural Resources Statistical Bulletin (Excerpts). China Natural Resources News, 13 April 2023; (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Zhu, L.; Guo, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yin, Y. Rainfall-Induced Failure Mechanisms of Cohesive Slopes in Deep Excavations. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2025, 43, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Xiao, J.; Tan, F.; Huang, C. Mechanisms of pile-soil stress and deformation in excavations under the coupled effects of excavation disturbance and extreme rainfall infiltration. Sci. Rep. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, A.W. The Use of the Slip Circle in the Stability Analysis of Slopes. Géotechnique 1955, 5, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janbu, N. Slope Stability Computations; Embankment Dam Engineering Casagrande Volume; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern, N.R.; Price, V.E. The Analysis of the Stability of General Slip Surfaces. Géotechnique 1965, 15, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozato, K.; Dolojan, N.L.J.; Touge, Y.; Kure, S.; Moriguchi, S.; Kawagoe, S.; Kazama, S.; Terada, K. Limit equilibrium method-based 3D slope stability analysis for wide area considering influence of rainfall. Eng. Geol. 2022, 308, 106808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Guo, R.; Liu, C. Study on Hybrid Stress Finite Elements of 3D Arbitrary Polyhedral Considering Gravity. Acta Mech. Solida Sin. 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, T. Stability of Steep Slopes on Hard Unweathered Rock. Geotechnique 1962, 12, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metya, S.; Bhattacharya, G. Probabilistic Stability Analysis of the Bois Brule Levee Considering the Effect of Spatial Variability of Soil Properties Based on a New Discretization Model. Indian Geotech. J. 2016, 46, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, D.V.; Lane, P.A. Slope stability analysis by finite elements. Géotechnique 2001, 51, 653–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Li, D.Q.; Cao, Z.J.; Tang, X.S.; Zhou, C.B. Monte Carlo simulation-based reliability design method for rock slopes. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2016, 35, 3794–3804. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tamimi, S.; Amadei, B.; Frangopol, D.M. Monte Carlo simulation of rock slope reliability. Comput. Struct. 1989, 33, 1495–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, B.; Adhikari, S. A reduced polynomial chaos expansion method for the stochastic finite element analysis. Sadhana Acad. Proc. Eng. Sci. 2012, 37, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, F.S. Slope Reliability and Response Surface Method. J. Geotech. Eng. Asce 1985, 111, 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Cheng, Z. Global Sensitivity Analysis of Structural Random Response Based on Polynomial Chaotic Expansion. Acad. J. Sci. Technol. 2025, 16, 78–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meulenaere, R.; Coppitters, D.; Sikkema, A.; Maertens, T.; Blondeau, J. Uncertainty Quantification for Thermodynamic Simulations with High-Dimensional Input Spaces Using Sparse Polynomial Chaos Expansion: Retrofit of a Large Thermal Power Plant. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanmarcke, J.H. Random Fields: Analysis and Synthesis; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1983; Available online: https://books.google.com.sg/books?hl=zh-CN&lr=&id=0MCxDV1bonAC&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&ots=LPdjpB2kSS&sig=3YdvFv-xnQRsWuUGRe3sZt-aSCI&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Wolfe, G.F.D.; Griffiths, D.V.; Huang, J. Probabilistic Slope Stability Analysis Of Embankment Dams Using Random Finite Elements (Rfem). In Proceedings of the Association of State Dam Safety Officials Annual Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 20–23 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Spencer, B.F.; Elnashai, A.S. Bayesian Updating of Fragility Functions using Hybrid Simulation. J. Struct. Eng. 2013, 139, 1160–1171. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/261987177_Bayesian_Updating_of_Fragility_Functions_Using_Hybrid_Simulation (accessed on 15 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, D.V.; Fentont, G.A. The Random Finite Element Method (RFEM) in Steady Seepage Analysis; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozato, K.; Sugo, D.; Dolojan, N.L.J.; Nomura, R.; Terada, K.; Takase, S.; Kaneko, K.; Moriguchi, S. Rapid prediction of rainfall-induced landslides over a wide area aided by a simulation-based surrogate model. Comput. Geotech. 2025, 188, 107480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshtegar, B.; Hasanipanah, M.; Nguyen-Thoi, T.; Yagiz, S.; Amnieh, H.B. Potential efficacy and application of a new statistical meta based-model to predict TBM performance. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 2021, 35, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, T.; Koch, M.C.; Papaioannou, I.; Fujisawa, K. Efficient Bayesian inversion for simultaneous estimation of geometry and spatial field using the Karhunen-Loève expansion. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2025, 441, 117960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Pan, W.; Zheng, X. A spectral-fast Voronoi framework based on multivariate Karhunen–Loève expansion for simulation of two-dimensional random fields. Appl. Math. Model. 2026, 150, 116422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhi, P. Reliability assessment of RAC chloride concentration using Karhunen–Loève expansion with digital-image kernels. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 245, 118352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Li, R.; Zhang, C.-S.; Chen, Z. Combined discontinuous and continuous Galerkin methods for fractured poroelastic media flow on polytopic grids. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2026, 474, 116986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Q.M.; Salahuddin, A.A. A polynomial extrapolation-based wavelet-Galerkin method for dynamic response reconstruction. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 102009. [Google Scholar]

- Blatman, G.; Sudret, B. Adaptive sparse polynomial chaos expansion based on least angle regression. J. Comput. Phys. 2011, 230, 2345–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, R.; Rao, B. Assessment of high dimensional model representation techniques for reliability analysis. Probab. Eng. Mech. 2009, 24, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Lin, J.K.D.; Chang, C. Design and analysis of computer experiment via dimensional analysis. Qual. Eng. 2018, 30, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudret, B. Global sensitivity analysis using polynomial chaos expansions. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2008, 93, 964–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, R.G.; Spanos, P.D. Stochastic Finite Elements: A Spectral Approach; Courier Corporation: Chelmsford, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Wang, D. Structural reliability analysis based on polynomial chaos, Voronoi cells and dimension reduction technique. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2019, 185, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marelli, L.N.; Sudret, S.B. UQLab User Manual–Polynomial Chaos Expansions; Technical Report; Report UQLab-V1.4-104; Chair of Risk, Safety and Uncertainty Quantification; ETH: Zurich, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Babacan, S.D.; Molina, R.; Katsaggelos, A.K. Bayesian compressive sensingusing Laplace priors. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2009, 19, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lataniotis, C.; Wicaksono, D.; Marelli, S.; Sudret, B. UQLab User Manual–Kriging (Gaussian Process Modeling); Technical Report; Report UQLab-V1.3-105; Chair of Risk, Safety and Uncertainty Quantification; ETH: Zurich, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Q.-J.; Zhang, R.-F.; Ye, X.-Y.; Li, Z.-W. An efficient method combining polynomial-chaos kriging and adaptive radial-based importance sampling for reliability analysis. Comput. Geotech. 2021, 140, 104434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöbi, R. Surrogate models for uncertainty quantification in the contextof imprecise probability modelling. In IBK Bericht; ETH: Zurich, Switzerland, 2019; p. 505. [Google Scholar]

- van Genuchten, M.T. A closed-form equation for predicting the hydraulic conductivity of unsaturated soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1980, 44, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Şener-Kaya, B.; Wayllace, A.; Godt, J.W. Analysis of rainfall-induced slope instability using a field of local factor of safety. Water Resour. Res. 2012, 48, 9524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W. Impact of Slope Runoff on Shallow Slope Stability; Zhejiang University: Hangzhou, China, 2023. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Nian, G.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, L.; Bao, M.; Zhou, Z. Treatment and application of two boundary conditions in slope rainfall infiltration. Rock. Soil Mech. 2020, 41, 4105–4115. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, G.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, L.; Bao, M. Seepage and stability analysis of fractured rock slopes based on the dual-medium model. J. Coal Sci. 2020, 45, 736–746. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X. Copula-Based Simulation of Cross-Correlation Stochastic Fields and Reliability Analysis of Soil Slopes. Ph.D. Thesis, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, China, 2020. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Prior Limitation | Targeted Innovation of the Proposed Method |

|---|---|

| Deterministic methods: Ignorance of parameter uncertainty and spatial variability | KLE random field modeling characterizes marginal distributions and spatial correlation of c and phi, replacing single-valued parameters with physically meaningful 2D spatial random fields. |

| Probabilistic methods: Efficiency bottlenecks (MCS) and dimensionality curse (PCE) | PCK surrogate model fuses PCE’s global approximation and Kriging’s local interpolation to balance accuracy and efficiency, reducing computational time by 2–3 orders of magnitude compared to direct MCS/RFEM. |

| Probabilistic methods: Neglect of time-varying effects | Dynamic simulation across distinct rainfall stages (e.g., initial infiltration, saturation, post-rainfall) tracks temporal evolution of safety factors and failure probability. |

| Lack of integrated multi-dimensional frameworks | Unifies uncertainty–spatial variability–time-varying effects into a single pipeline, enabling comprehensive characterization of slope risk evolution. |

| Modulus of Elasticity/MPa | Poisson’s Ratio | Dry Density/kg | Porosity | Saturated Permeability/m/h | VG Model Parameter Alpha | VG Model Parameter n | Residual Moisture Content | Deterministic Model c/kPa | Deterministic Model phi/° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | 0.3 | 1370 | 0.46 | 0.018 | 0.167 | 1.7 | 0.08 | 10.18 | 27.83 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhou, B.; Hou, K.; Sun, H.; Cheng, Q.; Wang, H. Probabilistic Analysis of Rainfall-Induced Slope Stability Using KL Expansion and Polynomial Chaos Kriging Surrogate Model. Geosciences 2026, 16, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences16010036

Zhou B, Hou K, Sun H, Cheng Q, Wang H. Probabilistic Analysis of Rainfall-Induced Slope Stability Using KL Expansion and Polynomial Chaos Kriging Surrogate Model. Geosciences. 2026; 16(1):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences16010036

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Binghao, Kepeng Hou, Huafen Sun, Qunzhi Cheng, and Honglin Wang. 2026. "Probabilistic Analysis of Rainfall-Induced Slope Stability Using KL Expansion and Polynomial Chaos Kriging Surrogate Model" Geosciences 16, no. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences16010036

APA StyleZhou, B., Hou, K., Sun, H., Cheng, Q., & Wang, H. (2026). Probabilistic Analysis of Rainfall-Induced Slope Stability Using KL Expansion and Polynomial Chaos Kriging Surrogate Model. Geosciences, 16(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences16010036