Magnetic ‘Fingerprinting’ of Sediments in Taizhou Bay: Implications for Provenance

Abstract

1. Introduction

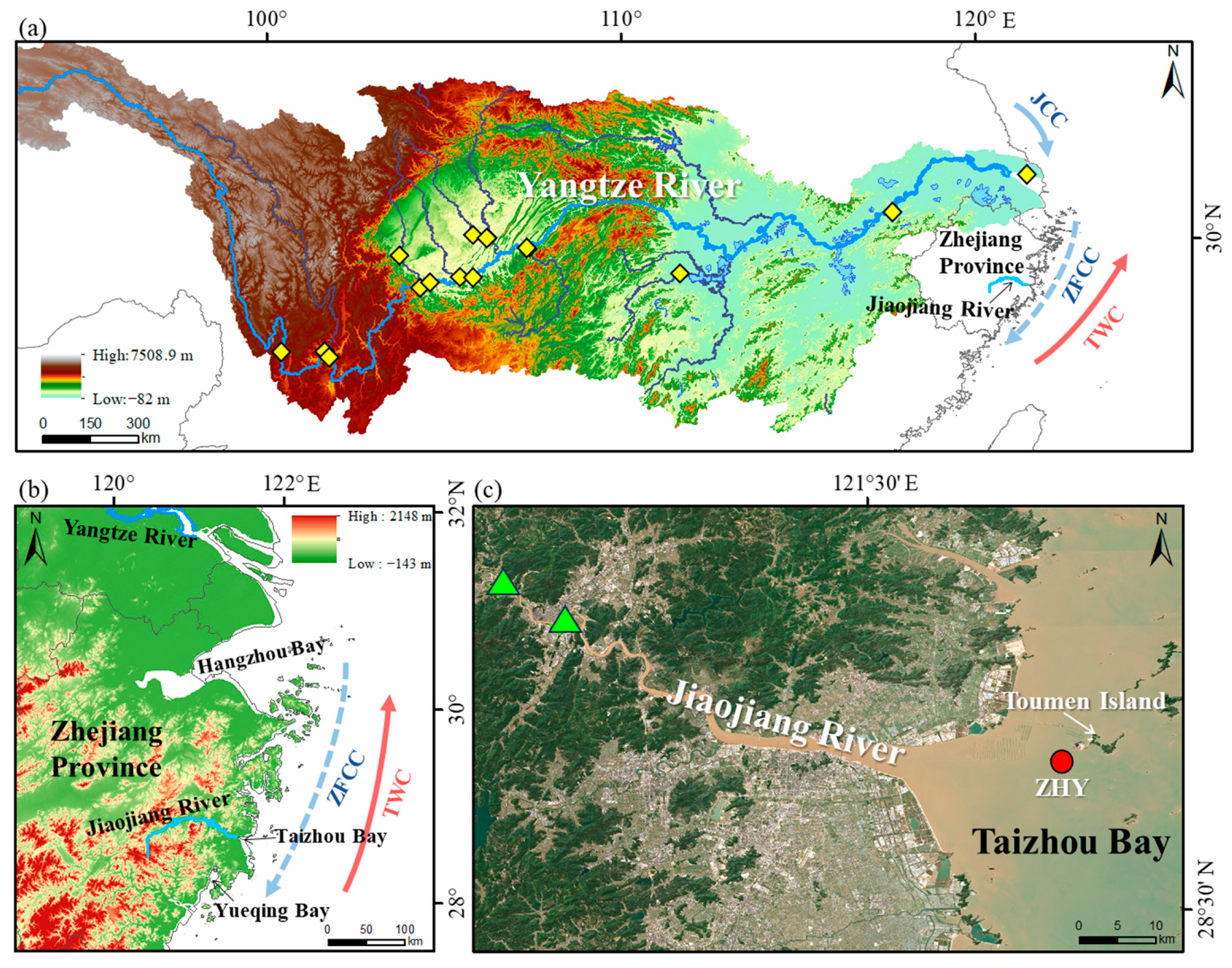

2. Study Area and Sampling

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sample Collection

3. Material and Methods

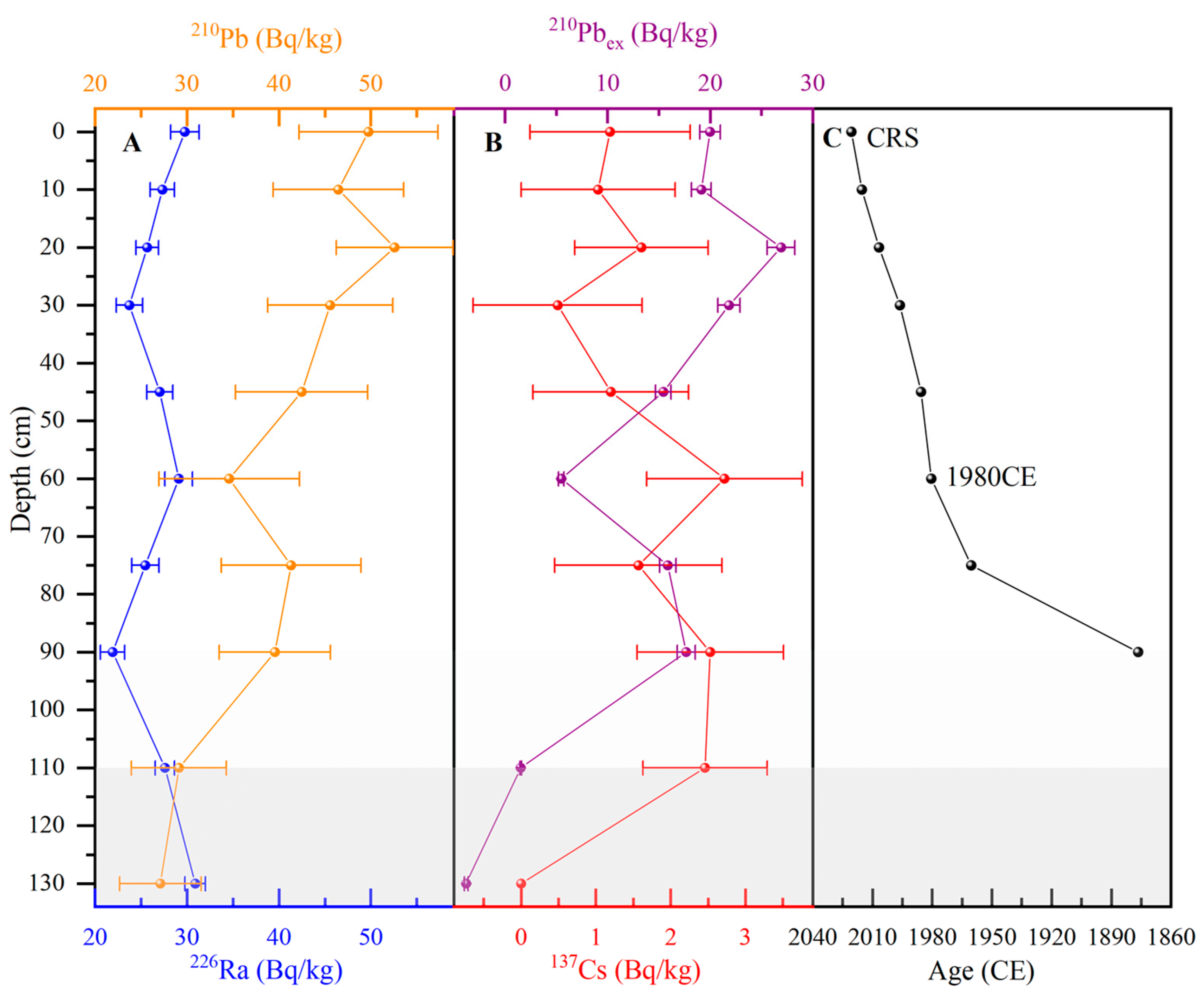

3.1. Dating Methods

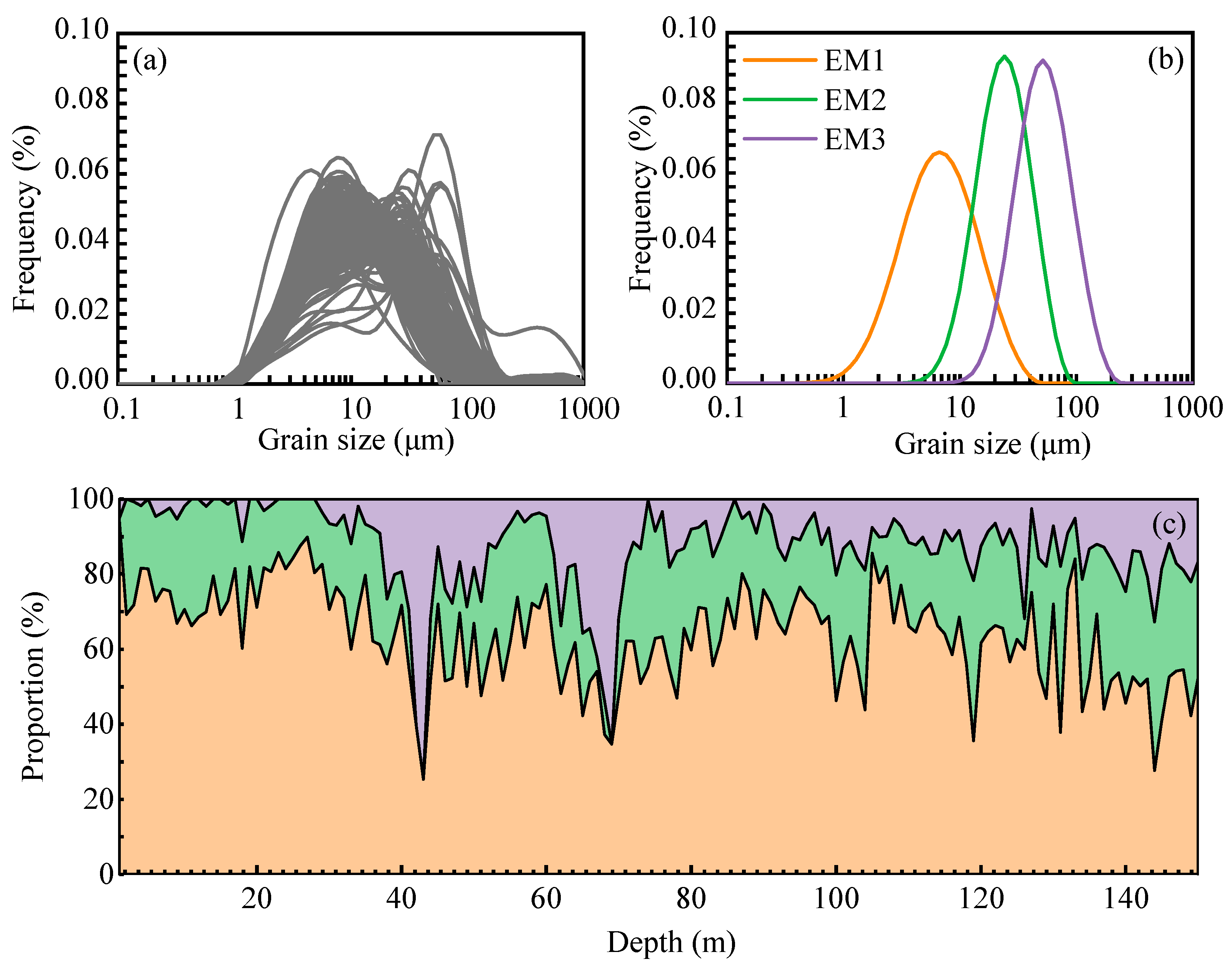

3.2. Subsection Grain Size and End-Member Modeling

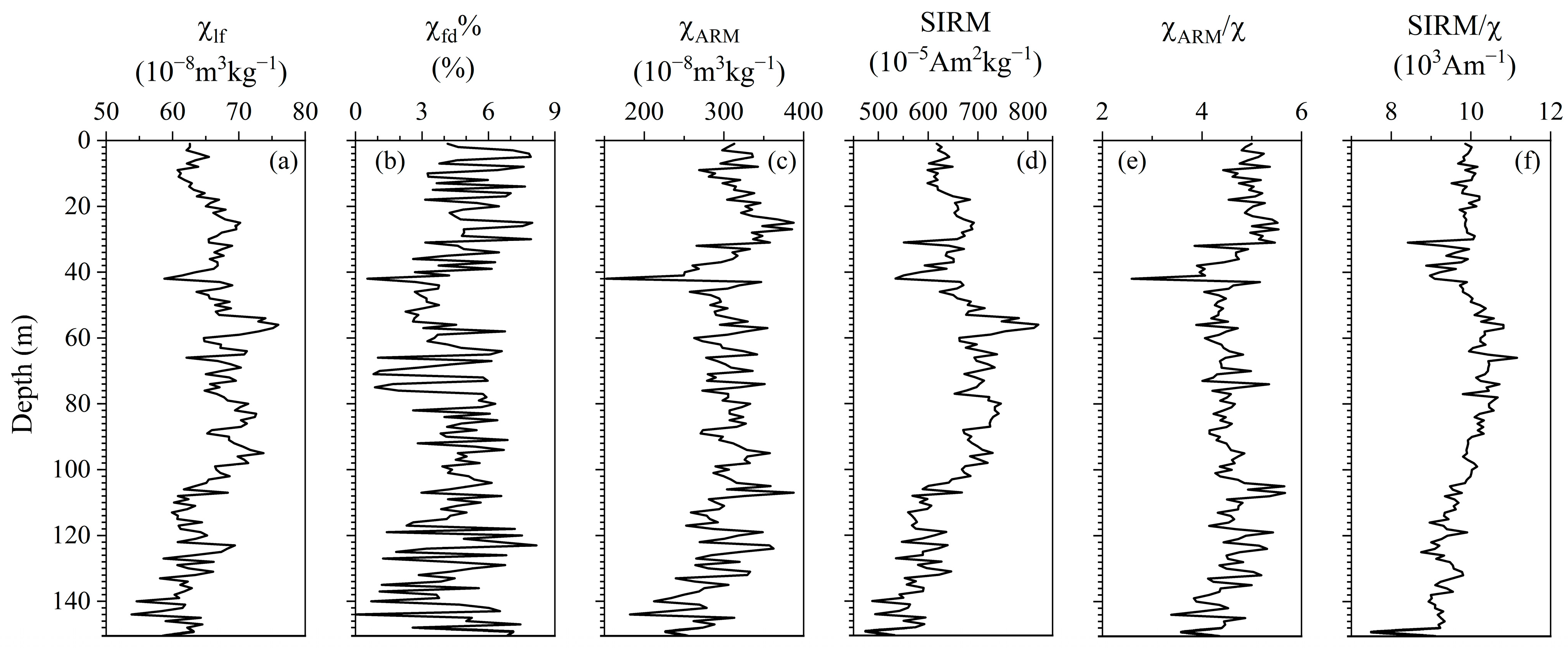

3.3. Magnetic Property Measurements

4. Results

4.1. Chronological Analysis

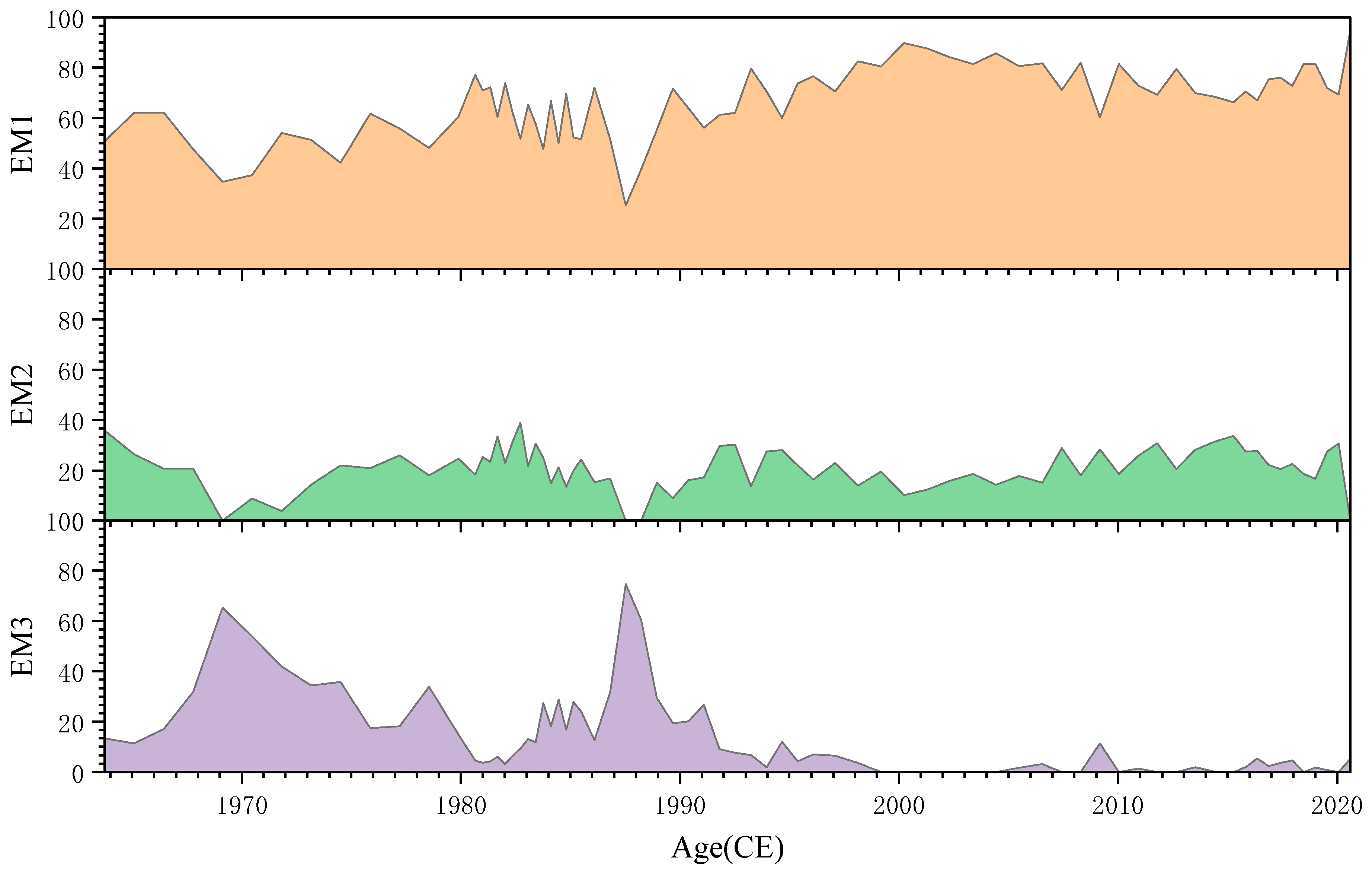

4.2. Grain Size Analysis

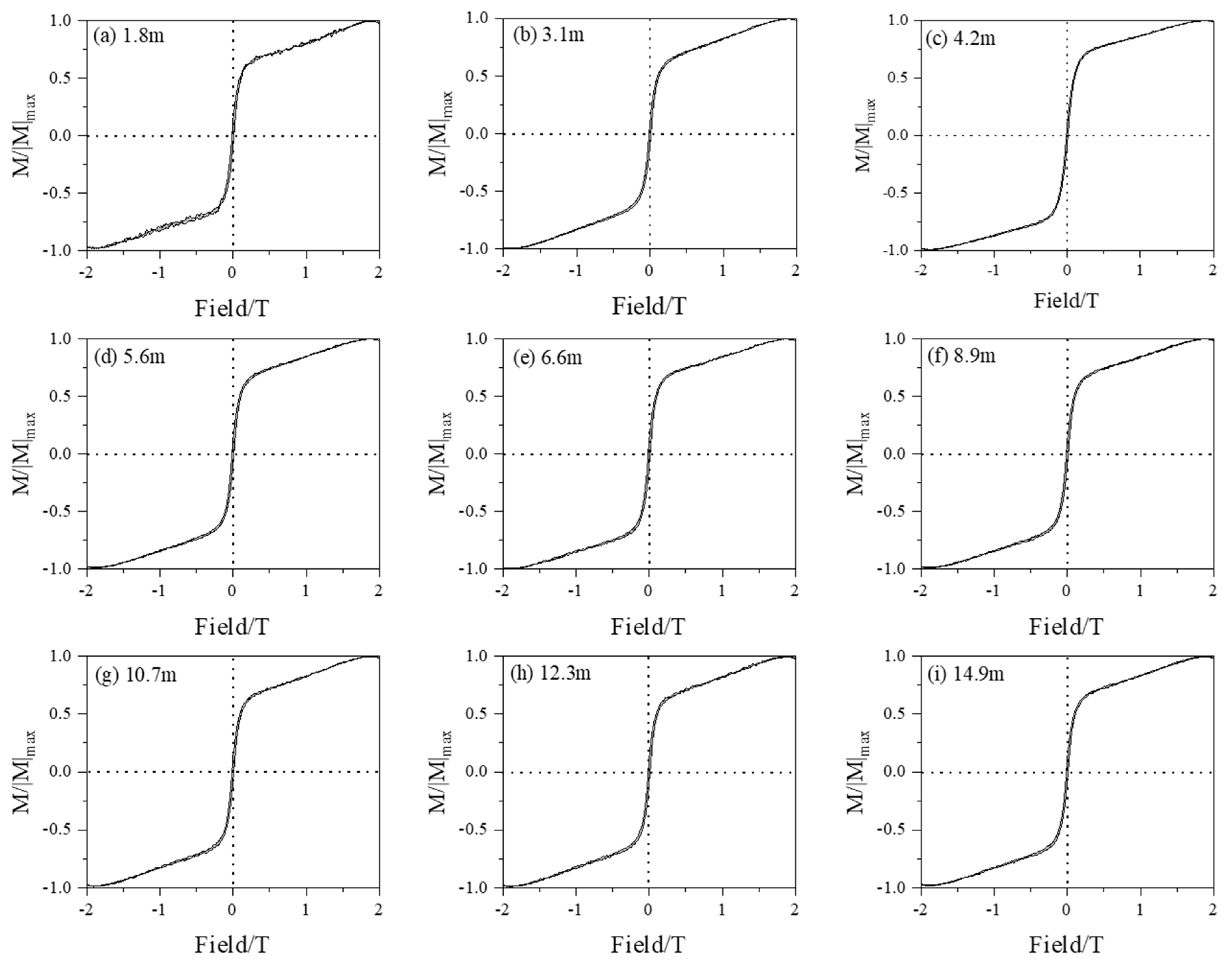

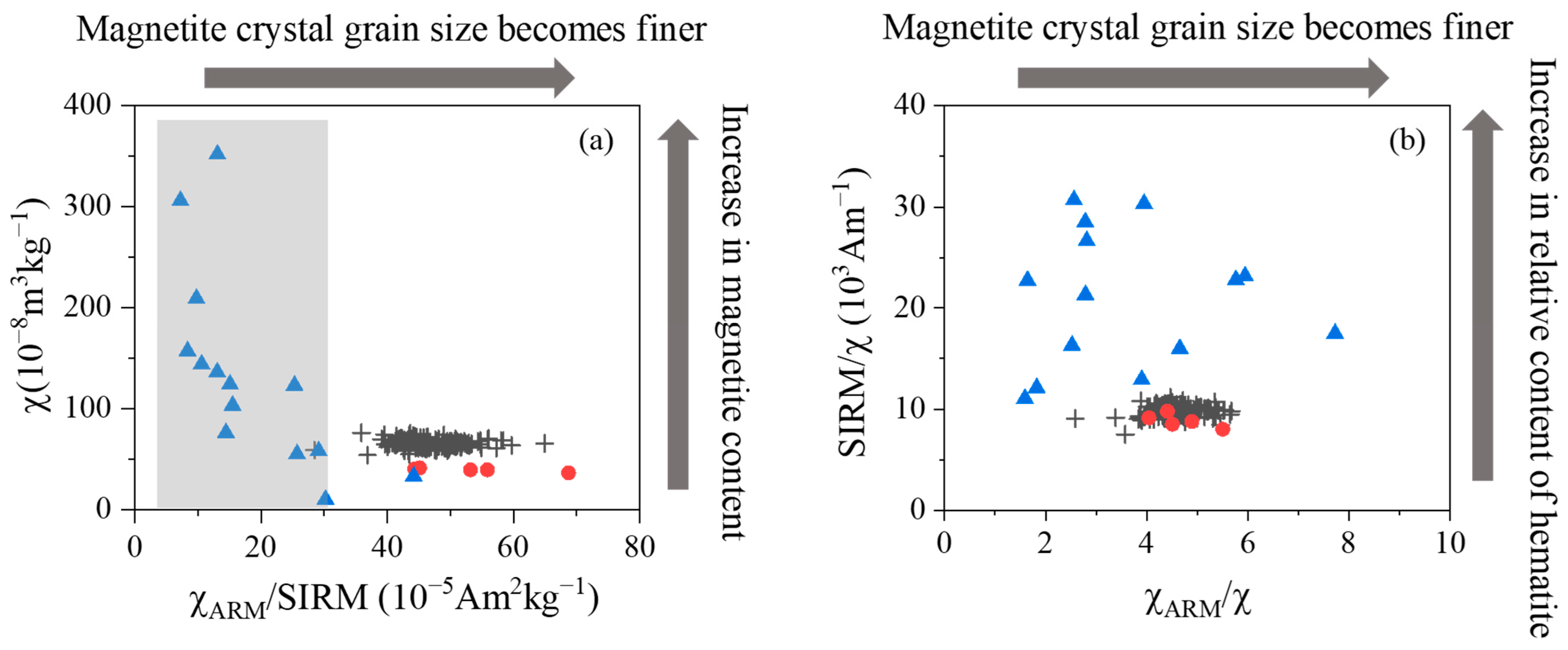

4.3. Magnetic Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Magnetic Evidence for Sediment Provenance in Taizhou Bay

5.2. End-Member Analysis Reveals a Decrease in Depositional Energy

5.3. Accelerated Sedimentation Rate Driven by Human Activities

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jia, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, S.; Wang, Q.; Wang, L.; Yang, L.; Xia, D.; Chen, F. No evidence for an anti-phased Holocene moisture regime in mountains and basins in Central Asian: Records from Ili loess, Xinjiang. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2021, 572, 110407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, J.; Fang, X.; Yang, S.; Nie, J.; Li, X. A rock magnetic study of loess from the West Kunlun Mountains. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2010, 115, B10101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Hao, Q.; Oldfield, F.; Bloemendal, J.; Deng, C.; Wang, L.; Song, Y.; Ge, J.; Wu, H.; Xu, B.; et al. New High-Temperature Dependence of Magnetic Susceptibility-Based Climofunction for Quantifying Paleoprecipitation From Chinese Loess. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2019, 20, 4273–4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, B.A. Palaeoclimatic records of the loess/palaeosol sequences of the Chinese Loess Plateau. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2016, 154, 23–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, B.A. Airborne Magnetite- and Iron-Rich Pollution Nanoparticles: Potential Neurotoxicants and Environmental Risk Factors for Neurodegenerative Disease, Including Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD 2019, 71, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Xia, D.-s.; Wang, B.; Liu, H.; Ma, X. Pollution monitoring using the leaf-deposited particulates and magnetism of the leaves of 23 plant species in a semi-arid city, Northwest China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 34898–34911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, D.; Wang, Y.; Jia, J.; Wei, H.; Fan, Y.; Jin, M.; Chen, F. Mountain loess or desert loess? New insight of the sources of Asian atmospheric dust based on mineral magnetic characterization of surface sediments in NW China. Atmos. Environ. 2020, 232, 117564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, B.A.; Mutch, T.J.; Cunningham, D. Magnetic and geochemical characteristics of Gobi Desert surface sediments: Implications for provenance of the Chinese Loess Plateau. Geology 2009, 37, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, R.; Meadows, M.; Sengupta, D.; Zhu, L. Sources of sediment in tidal flats off Zhejiang coast, southeast China. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2021, 39, 1245–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Wang, Y.; Xia, D.; Lu, H.; Gao, F. Dust Sources of Last Glacial Chinese Loess Based on the Iron Mineralogy of Fractionated Source Samples. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 2103–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, S.J.; Maher, B.A.; Bigg, G.R. Ocean circulation at the Last Glacial Maximum: A combined modeling and magnetic proxy-based study. Paleoceanography 2007, 22, PA2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, J.; Fang, X.; Kang, J.; Li, X.; Yan, M. Spatial and altitudinal variations in the magnetic properties of eolian deposits in the northern Tibetan Plateau and its adjacent regions: Implications for delineating the climatic boundary. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 208, 103271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Sun, Y.; Qiang, X.; Tada, R.; Hu, P.; Duan, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, J.; Su, K. Characterizing magnetic mineral assemblages of surface sediments from major Asian dust sources and implications for the Chinese loess magnetism. Earth Planets Space 2015, 67, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Lü, B.; Liu, X.; Du, J.; Chen, T.; Li, J. Chromaticity characteristics of soil profiles in the coastal areas of Fujian and Guangdong, southern China and their climatic significance. Quat. Int. 2023, 649, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Ji, J.; Barrón, V.; Torrent, J. Climatic thresholds for pedogenic iron oxides under aerobic conditions: Processes and their significance in paleoclimate reconstruction. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2016, 150, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Ji, J.; Balsam, W. Rainfall-dependent transformations of iron oxides in a tropical saprolite transect of Hainan Island, South China: Spectral and magnetic measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2011, 116, F03015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Lü, B.; Liu, X.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, X. Magnetic characteristics of purple soils in Wuyishan and their significance for pedogenesis. Quat. Sci. 2023, 43, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lü, B.; Liu, X.; Zheng, X.; Chen, Z.; Du, J. Different types of maghemite and their gensis in humid subtropical red soil derived from granite weathering crust. Quat. Sci. 2021, 41, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.H.; Zhang, W.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Ge, C.; Liu, J.; Bai, X.; Feng, H.; Yu, L. Magnetic properties of sediments of the Red River: Effect of sorting on the source-to-sink pathway and its implications for environmental reconstruction. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2016, 17, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, C.; Zhang, W.; Dong, C.; Wang, F.; Feng, H.; Qu, J.; Yu, L. Tracing sediment erosion in the yangtze river subaqueous delta using magnetic methods. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2017, 122, 2064–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.I.; Choi, J.Y.; Jung, H.S.; Rho, K.C.; Ahn, K.S. Recent sediment accumulation and origin of shelf mud deposits in the Yellow and East China Seas. Prog. Oceanogr. 2007, 73, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Li, A.; Liu, J.P.; Milliman, J.D.; Yang, Z.; Liu, C.-S.; Kao, S.-J.; Wan, S.; Xu, F. Provenance, structure, and formation of the mud wedge along inner continental shelf of the East China Sea: A synthesis of the Yangtze dispersal system. Mar. Geol. 2012, 291–294, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, A.; Dong, J.; Lu, J.; Huang, J.; Wan, S. Provenance discrimination of sediments in the Zhejiang-Fujian mud belt, East China Sea: Implications for the development of the mud depocenter. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2018, 151, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dalrymple, R.W.; Yang, S.-Y.; Lin, C.-M.; Wang, P. Provenance of Holocene sediments in the outer part of the Paleo-Qiantang River estuary, China. Mar. Geol. 2015, 366, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Liu, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, Z.; Hu, G.; Kong, X. Modern muddy deposit along the Zhejiang coast in the East China Sea: Response to large-scale human projects. Cont. Shelf Res. 2016, 130, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Hu, Z.X.; Zhang, W.G.; Ji, R.; Nguyen, T.T.H. Influence of provenance and hydrodynamic sorting on the magnetic properties and geochemistry of sediments of the Oujiang River, China. Mar. Geol. 2017, 387, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, N.J.; Phinn, S.R.; DeWitt, M.; Ferrari, R.; Johnston, R.; Lyons, M.B.; Clinton, N.; Thau, D.; Fuller, R.A. The global distribution and trajectory of tidal flats. Nature 2019, 565, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Su, N.; Zhu, C.; He, Q. How have the river discharges and sediment loads changed in the Changjiang River basin downstream of the Three Gorges Dam? J. Hydrol. 2018, 560, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Water Resources of the People’s Republic of China. China River Sediment Bulletin 2019; China Water & Power Press: Beijing, China, 2020; p. 74. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, G.; Hu, F.; Zhang, Z. The sediment source and development mechanics of the muddy coast in the East Zhejiang. Donghai Mar. Sci. 1997, 15, 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, L.; Hu, K.; Zhang, X.; Xiong, W.; Wang, N.; Zhou, W.; Li, F. Sedimentary Magnetic Characteristics and Provenance Identification of Muddy Tidal Flats Along the Coast of Zhejiang and Fujian. Acta Sedimentol. Sin. 2022, 40, 774–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Jia, J.; Zhou, R.; Wang, B. Source tracing of tidal flats in Zhejiang coastal zone: Evidence from magnetic mineral inclusions. J. Earth Environ. 2024, 15, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, E.; Yang, S.; Wu, H.; Yang, C.; Li, C.; Liu, J.T. Kuroshio subsurface water feeds the wintertime Taiwan Warm Current on the inner East China Sea shelf. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2016, 121, 4790–4803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.P.; Xu, K.H.; Li, A.C.; Milliman, J.D.; Velozzi, D.M.; Xiao, S.B.; Yang, Z.S. Flux and fate of yangtze river sediment delivered to the east China sea. Geomorphology 2007, 85, 208–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yang, S.; Zhang, W. Magnetic properties of sediments from major rivers, aeolian dust, loess soil and desert in China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2012, 45, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleby, P.G.; Oldfield, F. The calculation of lead-210 dates assuming a constant rate of supply of unsupported 210Pb to the sediment. Catena 1978, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzyk, Z.Z.A.; Gobeil, C.; Macdonald, R.W. 210Pb and 137Cs in margin sediments of the Arctic Ocean: Controls on boundary scavenging. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2013, 27, 422–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi Dehkordi, N.; Khaledi Darvishan, A.; Porto, P.; Zare, M.R. Erosional history by combining 210Pbex and 137Cs methods with sediment fingerprinting and measurements. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Cabeza, J.A.; Ruiz-Fernández, A.C. 210Pb sediment radiochronology: An integrated formulation and classification of dating models. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2012, 82, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsumune, D.; Tsubono, T.; Aoyama, M.; Hirose, K. Distribution of oceanic 137Cs from the Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant simulated numerically by a regional ocean model. J Environ. Radioact. 2012, 111, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; An, Z. Pretreated methods on loess-palaeosol samples granulometry. Chin. Sci. Bull. 1998, 43, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weltje, G.J. End-member modeling of compositional data: Numerical-statistical algorithms for solving the explicit mixing problem. Math. Geol. 1997, 29, 503–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Sun, Y. QGrain: An open-source and easy-to-use software for the comprehensive analysis of grain size distributions. Sediment. Geol. 2021, 423, 105980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrent, J.; Barrón, V.; Liu, Q. Magnetic enhancement is linked to and precedes hematite formation in aerobic soil. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, 2005GL024818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binford, M.W. Calculation and uncertainty analysis of 210Pb dates for PIRLA project lake sediment cores. J. Paleolimnol. 1990, 3, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdoba, F.E.; Piovano, E.L.; Guerra, L.; Mulsow, S.; Sylvestre, F.; Zárate, M. Independent time markers validate 210Pb chronologies for two shallow argentine lakes in southern pampas. Quat. Int. 2017, 438, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino-López, M.A.; Blaauw, M.; Christen, J.A.; Sanderson, N.K. Bayesian analysis of 210pb dating. J. Agric. Biol. Environ. Stat. 2018, 23, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Deng, C.; Torrent, J.; Zhu, R. Review of recent developments in mineral magnetism of the Chinese loess. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2007, 26, 368–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldfield, F.; Crowther, J. Establishing fire incidence in temperate soils using magnetic measurements. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2007, 249, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Jin, C.; Hu, P.; Jiang, Z.; Ge, K.; Roberts, A.P. Magnetostratigraphy of Chinese loess–paleosol sequences. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2015, 150, 139–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Roberts, A.P.; Larrasoaña, J.C.; Banerjee, S.K.; Guyodo, Y.; Tauxe, L.; Oldfield, F. Environmental magnetism: Principles and applications. Rev. Geophys. 2012, 50, 2012RG000393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, K.; Williams, W.; Liu, Q.; Yu, Y. Effects of the core-shell structure on the magnetic properties of partially oxidized magnetite grains: Experimental and micromagnetic investigations. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2014, 15, 2021–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, M.F.; Zhao, B.; Chen, L.; Ding, Y.; Wang, N.; Ye, X.; Gao, C.; Duan, X.; Yao, P. Impacts of sea level rise and climate change on the sources, preservation and thermal stability of sedimentary organic carbon in the East China Sea inner shelf since the last deglaciation. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2025, 362, 109416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Li, X.; Tang, X.; Sun, X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, D.; Xu, L.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, H.; Wang, Y.; et al. The seas around China in a warming climate. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J. Influence of the Three Gorges Dam on the transport and sorting of coarse and fine sediments downstream of the dam. J. Hydrol. 2022, 615, 128654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.L.; Milliman, J.D.; Xu, K.H.; Deng, B.; Zhang, X.Y.; Luo, X.X. Downstream sedimentary and geomorphic impacts of the three gorges dam on the yangtze river. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2014, 138, 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H.; Jia, Y. Sedimentary Records of Paleoflood Events in the Desert Section of the Upper Yellow River Since the Late Quaternary. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C. Numerical Simulation Research on the Sediment Settling Characteristics in the Strong Tidal Current Estuarine Environment—A Case Study of the Jiaojiang Estuary in Zhejiang Coastal Area. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, W.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, X. Influences of variations in runoff and tide on spatial and temporal distribution of sediment concentration in Jiaojiang River estuary. Hydro-Sci. Eng. 2016, 3, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Yin, P.; Chu, Z.; Tian, Y.; Cao, K.; Li, M.; Guang, X.; Gao, B.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Y.; et al. Characteristics and influencing factors of water and sediment changes in Jiaojiang River Basin. Mar. Geol. Front. 2022, 38, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Sen, Z.; Zheng, H.; Pan, G. Response of estuarine erosion and deposition to reclamation in estuary. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Eng. Sci.) 2016, 50, 1791–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Pan, G.; Chen, P. Coastline Change of the Taizhou Bay and Its Driving Force Over the Last 30 Years. Coast. Eng. 2015, 34, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Huang, J.; Zhu, Y. Analysis on Changes in Coastline and Reclamation and its Causes Based on 40-year Satellite Data in Jiaojiang-Taizhou Bay. Geol. Rev. 2017, 63, 337–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, M.; Jiang, G. Influence of renovation project in Jiaojiang on estuary dynamic and evolution of river bed. J. Water Resour. Water Eng. 2011, 22, 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C. Responses of the Jiaojiang Estuary to Reclamation Projects. Doctoral Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Tao, J.; Zhang, C.; Dai, W.; Xu, F. Effect of the large-scale reclamation of tidal flats on the hydrodynamic characteristics in the Taizhou Bay. Mar. Sci. Bull. 2015, 34, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Wal, D.; Pye, K.; Neal, A. Long-term morphological change in the Ribble Estuary, northwest England. Mar. Geol. 2002, 189, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, F.; Bismuth, E.; Verney, R. Unraveling the impacts of meteorological and anthropogenic changes on sediment fluxes along an estuary-sea continuum. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Wei, X.; Mo, W.; Wu, C.; Bao, Y. A long-term numerical model of mophodynamic evolution and its applicationto Modaomen Estuary. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2012, 34, 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- Siemes, R.W.A.; Duong, T.M.; Borsje, B.W.; Hulscher, S.J.M.H. Fine Sediment Dynamics Affected by Large-Scale Interventions; A 3D Modelling Study of An Engineered Estuary. Estuaries Coasts 2025, 49, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, L.; Chen, P.; Xie, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, N.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shang, J.; Jia, J. Magnetic ‘Fingerprinting’ of Sediments in Taizhou Bay: Implications for Provenance. Geosciences 2026, 16, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences16010020

Yang L, Chen P, Xie Y, Liu S, Chen N, Tian Y, Zhang X, Shang J, Jia J. Magnetic ‘Fingerprinting’ of Sediments in Taizhou Bay: Implications for Provenance. Geosciences. 2026; 16(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences16010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Lei, Pinjing Chen, Yongqing Xie, Sisi Liu, Nuo Chen, Yuan Tian, Xu Zhang, Jiahan Shang, and Jia Jia. 2026. "Magnetic ‘Fingerprinting’ of Sediments in Taizhou Bay: Implications for Provenance" Geosciences 16, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences16010020

APA StyleYang, L., Chen, P., Xie, Y., Liu, S., Chen, N., Tian, Y., Zhang, X., Shang, J., & Jia, J. (2026). Magnetic ‘Fingerprinting’ of Sediments in Taizhou Bay: Implications for Provenance. Geosciences, 16(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences16010020