An Animal Welfare Risk Assessment Process for Zoos

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Need for Appropriate Welfare Strategies in Zoos

1.2. Resource-Based and Animal-Based Welfare Assessments

1.3. Zoo Animal Welfare Assessment Approaches

1.4. Developing an Animal Welfare Risk Assessment Process

2. Materials and Methods—Description of Process

2.1. Sites

2.2. Description of the Process

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Reporting Results

3. Results

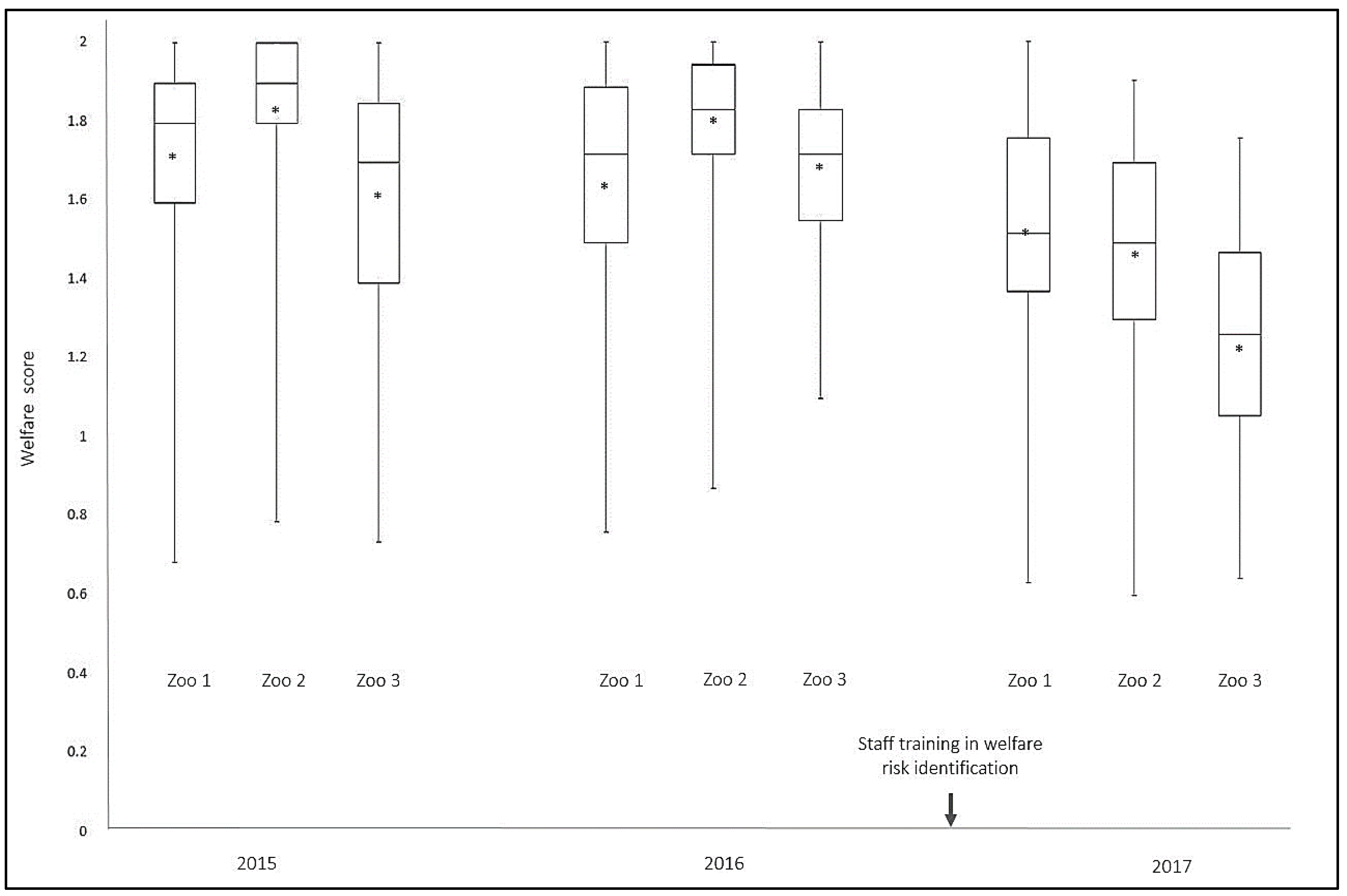

3.1. Demonstration of Use

3.2. Indicator Level Evaluation

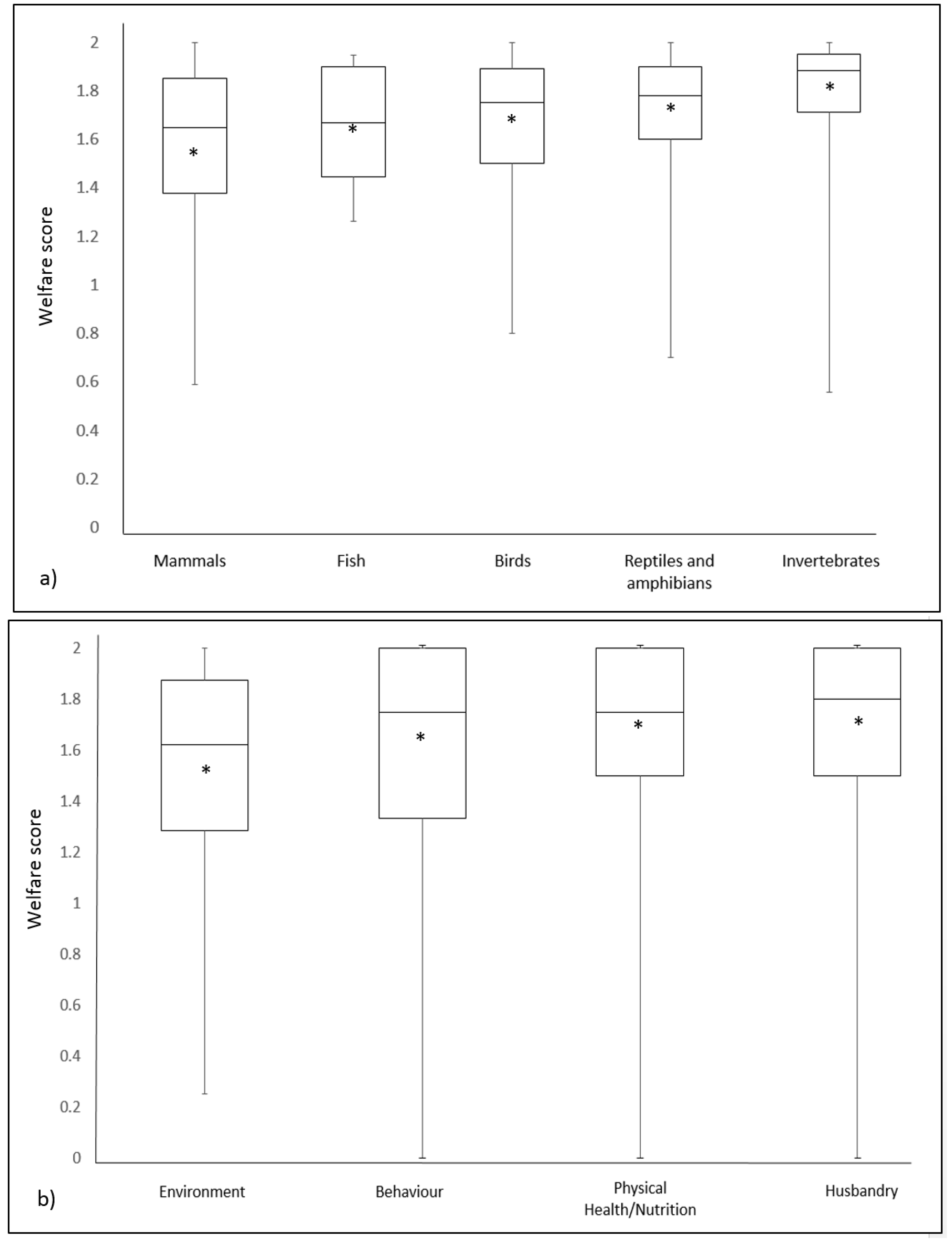

3.3. Taxonomic and Welfare Domain Trends

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Trial Results

4.2. The Value of the Process

4.3. Other Considerations and Limitations of Use

5. Conclusions

Author contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gracia, A. The determinants of the intention to purchase animal welfare-friendly meat products in Spain. Anim. Welf. 2013, 22, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, C.J.; Izmirli, S.; Aldavood, S.J.; Alonso, M.; Choe, B.I.; Hanlon, A.; Handziska, A.; Illmann, G.; Keeling, L.; Kennedy, M.; et al. Students’ attitudes to animal welfare and rights in Europe and Asia. Anim. Welf. 2012, 21, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prickett, R.W.; Norwood, F.B.; Lusk, J.L. Consumer preferences for farm animal welfare: Results from a telephone survey of US households. Anim. Welf. 2010, 19, 335–347. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhonacker, F.; Verbeke, W.; Van Poucke, E.; Tuyttens, F.A.M. Do citizens and farmers interpret the concept of farm animal welfare differently? Livest. Sci. 2008, 116, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broom, D.M. Considering animals’ feelings: Précis of Sentience and animal welfare (Broom 2014). Anim. Sentience Interdiscip. J. Anim. Feel. 2016, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Marchant-Forde, J.N. The science of animal behavior and welfare: Challenges, opportunities, and global perspective. Front. Vet. Sci. 2015, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, M.; Diez-Leon, M.; Mason, G. Animal welfare science: Recent publication trends and future research priorities. Int. J. Comp. Psychol. 2014, 27, 80–100. [Google Scholar]

- Maple, T.L.; Perdue, B.M. Zoo Animal Welfare; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013; p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J.; Hughes, K.; Dierking, L. Conservation learning in wildlife tourism settings: Lessons from research in zoos and aquariums. Environ. Educ. Res. 2007, 13, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, N.; Cohen, S. The public face of zoos: Images of entertainment, education and conservation. Anthrozoös 2011, 24, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gusset, M.; Dick, G. The global reach of zoos and aquariums in visitor numbers and conservation expenditures. Zoo Biol. 2011, 30, 566–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moorhouse, T.P.; D’Cruze, N.C.; Macdonald, D.W. The effect of priming, nationality and greenwashing on preferences for wildlife tourist attractions. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2017, 12, 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.J. Visitor reaction to pacing behavior: Influence on the perception of animal care and interest in supporting zoological institutions. Zoo Biol. 2012, 31, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashaw, M.J.; Gibson, M.D.; Schowe, D.M.; Kucher, A.S. Does enrichment improve reptile welfare? Leopard geckos (Eublepharis macularius) respond to five types of environmental enrichment. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 184, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, A.C.; Palme, R.; Moreira, N. How environmental enrichment affects behavioral and glucocorticoid responses in captive blue-and-yellow macaws (Ara ararauna). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 201, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagman, J.D.; Lukas, K.E.; Dennis, P.M.; Willis, M.A.; Carroscia, J.; Gindlesperger, C.; Schook, M.W. A work-for-food enrichment program increases exploration and decreases stereotypies in four species of bears. Zoo Biol. 2018, 37, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanson, K.V.; Wielebnowski, N.C. Effect of housing and husbandry practices on adrenocortical activity in captive Canada lynx (Lynx canadensis). Anim. Welf. 2013, 22, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.J.; Ivy, J.A.; Vicino, G.A.; Schork, I.G. Impacts of natural history and exhibit factors on carnivore welfare. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2018, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, S.R.; Schapiro, S.J.; Hau, J.; Lukas, K.E. Space use as an indicator of enclosure appropriateness: A novel measure of captive animal welfare. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 121, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan, C.L.; Hogan, J.N.; Bonaparte-Saller, M.K.; Mench, J.A. Housing and social environments of African (Loxodonta africana) and Asian (Elephas maximus) elephants in North American zoos. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baird, B.A.; Kuhar, C.W.; Lukas, K.E.; Amendolagine, L.A.; Fuller, G.A.; Nemet, J.; Willis, M.A.; Schook, M.W. Program animal welfare: Using behavioral and physiological measures to assess the well-being of animals used for education programs in zoos. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 176, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomfield, R.C.; Gillespie, G.R.; Kerswell, K.J.; Butler, K.L.; Hemsworth, P.H. Effect of partial covering of the visitor viewing area window on positioning and orientation of zoo orangutans: A preference test. Zoo Boil. 2015, 34, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherwen, S.L.; Magrath, M.J.; Butler, K.L.; Hemsworth, P.H. Little penguins, Eudyptula minor, show increased avoidance, aggression and vigilance in response to zoo visitors. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2015, 168, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwen, S.L.; Harvey, T.J.; Magrath, M.J.; Butler, K.L.; Fanson, K.V.; Hemsworth, P.H. Effects of visual contact with zoo visitors on black-capped capuchin welfare. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2015, 167, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whay, H.R. The journey to animal welfare improvement. Anim. Welf. 2007, 16, 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Appleby, M.C.; Hughes, B.O.; Mench, J.A.; Olsson, A. Animal Welfare, 2nd ed.; CAB International Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Whay, H.R.; Main, D.C.J.; Green, L.E.; Webster, A.J.F. Assessment of the welfare of dairy cattle using animal-based measurements: Direct observations and investigation of farm records. Vet. Rec. 2003, 153, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitham, J.C.; Wielebnowski, N. Animal-based welfare monitoring: Using keeper ratings as an assessment tool. Zoo Biol. 2009, 28, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitham, J.C.; Wielebnowski, N. New directions for zoo animal welfare science. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2013, 147, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J. Animal Welfare: Limping towards Eden; UFAW Animal Welfare Series; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, D. Understanding Animal Welfare: The Science in Its Cultural Context; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, J.C. Programmatic approaches to assessing and improving animal welfare in zoos and aquariums. Zoo Biol. 2009, 28, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellor, D.J.; Patterson-Kane, E.; Stafford, K.J. The Sciences of Animal Welfare; UFAW Animal Welfare Series; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, J.C.; Lindberg, A.C.; Main, D.C.; Whay, H.R. Assessment of the welfare of working horses, mules and donkeys, using health and behaviour parameters. Prev. Vet. Med. 2005, 69, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellor, D.J. Operational details of the Five Domains Model and its key applications to the assessment and management of animal welfare. Animals 2017, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlstead, K.; Mellen, J.; Kleiman, D.G. Black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis) in U.S. zoos: I. Individual behavior profiles and their relationship to breeding success. Zoo Biol. 1999, 18, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielebnowski, N.C. Behavioral differences as predictors of breeding status in captive cheetahs. Zoo Biol. 1999, 18, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wielebnowski, N.C.; Fletchall, N.; Carlstead, K.; Busso, J.M.; Brown, J.L. Noninvasive assessment of adrenal activity associated with husbandry and behavioral factors in the North American clouded leopard population. Zoo Biol. 2002, 21, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orban, D.A.; Soltis, J.; Perkins, L.; Mellen, J.D. Sound at the zoo: Using animal monitoring, sound measurement, and noise reduction in zoo animal management. Zoo Biol. 2017, 36, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justice, W.S.; O’Brien, M.F.; Szyszka, O.; Shotton, J.; Gilmour, J.E.; Riordan, P.; Wolfensohn, S. Adaptation of the animal welfare assessment grid (AWAG) for monitoring animal welfare in zoological collections. Vet. Rec. 2017, 181, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clegg, I.L.; Borger-Turner, J.L.; Eskelinen, H.C. C-Well: The development of a welfare assessment index for captive bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). Anim. Welf. 2015, 24, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botreau, R.; Veissier, I.; Butterworth, A.; Bracke, M.B.M.; Keeling, L.J. Definition of criteria for overall assessment of animal welfare. Anim. Welf. 2007, 16, 225–228. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan, R.; Carter, S.; Allard, S. A universal animal welfare framework for zoos. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2015, 18, S1–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoo Monitor. Available online: www.zoomonitor.org (accessed on 18 July 2018).

- AWARE. Available online: https://www.aware.institute/ (accessed on 19 July 2018).

- Mellor, D.J.; Hunt, S.; Gusset, M. Caring for Wildlife: The World Zoo and Aquarium Animal Welfare Strategy; WAZA Executive Office: Gland, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 1–87. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, D.J. Positive animal welfare states and reference standards for welfare assessment. N. Z. Vet. J. 2015, 63, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellor, D.J.; Beausoleil, N.J. Extending the “Five Domains” model for animal welfare assessment to incorporate positive welfare states. Anim. Welf. 2015, 24, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeates, J. Naturalness and Animal Welfare. Animals 2018, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemsworth, P.H.; Coleman, G.; Sherwen, S.L. Human Contact. In Animal Welfare, 3rd ed.; Appleby, M.C., Olsson, A.S., Galind, F., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, K.A.; Bethell, E.J.; Jacobson, S.L.; Egelkamp, C.; Hopper, L.M.; Ross, S.R. Evaluating mood changes in response to anthropogenic noise with a response-slowing task in three species of zoo-housed primates. Anim. Behav. Cognit. 2018, 5, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quadros, S.; Goulart, V.D.; Passos, L.; Vecci, M.A.; Young, R.J. Zoo visitor effect on mammal behaviour: Does noise matter? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 156, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, G.; Kuhar, C.W.; Dennis, P.M.; Lukas, K.E. A Survey of Husbandry Practices for Lorisid Primates in North American Zoos and Related Facilities. Zoo Biol. 2013, 32, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashaw, M.J.; Kelling, A.S.; Bloomsmith, M.A.; Maple, T.L. Environmental Effects on the Behavior of Zoo-housed Lions and Tigers, with a Case Study of the Effects of a Visual Barrier on Pacing. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2007, 10, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellen, J.D. Factors influencing reproductive success in small captive exotic felids (Felis spp.): A multiple regression analysis. Zoo Biol. 1991, 10, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosey, G.; Melfi, V. Human–animal bonds between zoo professionals and the animals in their care. Zoo Biol. 2012, 31, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melfi, V.A. There are big gaps in our knowledge, and thus approach, to zoo animal welfare: A case for evidence-based zoo animal management. Zoo Biol. 2009, 28, 574–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maple, T.L. Empirical zoo: Opportunities and challenges to a scientific zoo biology. Zoo Biol. 2008, 27, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Environment (Physical/Social) | Focus of the Question |

| Space allowance |

| Complexity: provision of species-appropriate behavioural opportunities in enclosure |

| Substrate quality and variation |

| Sensory environment: vision, sound, olfactory, and tactile |

| Animal safety |

| Access to appropriate thermal range |

| Social group |

| Facilities to allow effective management of the individual or group |

| Behaviour | |

| Behavioural opportunities through enrichment |

| Time spent engaged in various behaviours |

| Presence or absence and frequency of abnormal behaviour |

| Range of behavioural repertoire observed |

| Food presentation for behavioural opportunities |

| Physical Health/Nutrition | |

| Diet and drinking water |

| Body condition (including weight and coat/feather/skin condition) |

| Proactive health care; injury or disease |

| Husbandry | |

| Time available to monitor, as well as physical ability to check on animals |

| Human-animal relationships |

| Flexibility, predictability of routines, and choice |

| Training for future health management |

| Score | Description |

|---|---|

| Resource-Based Risk Level | |

| 0 | High risk: E.g., resource considered to be inadequate for animal and likely to have welfare implications |

| 1 | Moderate risk: E.g., resource considered to be suboptimal and improvements needed |

| 2 | No observable risk: E.g., resource provision considered to be good and species-appropriate according to natural behavioural biology |

| Animal-Based Welfare Level | |

| 0 | Poor: E.g., animals either under or over weight; behavioural abnormality present; limited behavioural diversity observed compared to that expected for the species; shows little engagement with and is excessively fearful of keepers |

| 1 | Moderate: E.g., animals slightly over or under weight; have observed signs of behavioural abnormality but not frequent; displays limited behavioural repertoire; somewhat engaged with environment and keepers |

| 2 | Good: E.g., animals in good condition; no signs of behavioural abnormality; displays high levels of behavioural diversity as expected for the species; appears engaged in environment and with keepers |

| Unknown | Team considers they do not have information critical to making a judgement |

| Measure | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zoo 1 | |||

| Number of enclosures assessed | 101 | 93 | 107 |

| Average welfare risk score | 1.73 | 1.67 | 1.50 |

| Standard error | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Median welfare risk | 1.80 | 1.72 | 1.5 |

| Zoo 2 | |||

| Number of enclosures assessed | 74 | 65 | 63 |

| Average welfare risk score | 1.82 | 1.80 | 1.45 |

| Standard error | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Median welfare risk | 1.90 | 1.83 | 1.47 |

| Zoo 3 | |||

| Number of enclosures assessed | 45 | 44 | 36 |

| Average welfare risk score | 1.61 | 1.69 | 1.21 |

| Standard error | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| Median welfare risk | 1.70 | 1.72 | 1.24 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sherwen, S.L.; Hemsworth, L.M.; Beausoleil, N.J.; Embury, A.; Mellor, D.J. An Animal Welfare Risk Assessment Process for Zoos. Animals 2018, 8, 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8080130

Sherwen SL, Hemsworth LM, Beausoleil NJ, Embury A, Mellor DJ. An Animal Welfare Risk Assessment Process for Zoos. Animals. 2018; 8(8):130. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8080130

Chicago/Turabian StyleSherwen, Sally L., Lauren M. Hemsworth, Ngaio J. Beausoleil, Amanda Embury, and David J. Mellor. 2018. "An Animal Welfare Risk Assessment Process for Zoos" Animals 8, no. 8: 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8080130

APA StyleSherwen, S. L., Hemsworth, L. M., Beausoleil, N. J., Embury, A., & Mellor, D. J. (2018). An Animal Welfare Risk Assessment Process for Zoos. Animals, 8(8), 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8080130