Jump Horse Safety: Reconciling Public Debate and Australian Thoroughbred Jump Racing Data, 2012–2014

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

| Locations of races | Restricted to 15 South Australia and Victorian race courses, predominantly non-Metropolitan. |

| Type of races | Two thirds hurdle races, one-third steeplechases. |

| Regulatory bodies | Administered under state-based Local Rules of Racing by Thoroughbred Racing South Australia (TRSA) and Racing Victoria (RVL). |

| Industry bodies | Australian Jumping Racing Association (AJRA). |

| Race regulations | Specify minimum weight (64 kg); course condition rating; height, number and placement of obstacles; maximum field size; use of whips; horse boots; etc. |

| Industry review | Seven safety performance reviews by regulatory bodies since 1994. |

| Race review | In addition to the TRSA and VRL Stewards Committee review, TRSA and VRL Jump Review Panels review each horse’s jump at each obstacle in each race and may refer horse or jockey to undergo further training. The Panel includes a former jump jockey who can provide individual coaching if needed. |

| Qualification | Horses, trainers and jockeys must undergo qualification training and trials, overseen by VRL and TRSA, in order to compete in a maiden hurdle race. Horses that progress to open hurdle races are then eligible to qualify for steeplechase races. Mandatory trainer and jockey skills workshops held annually. |

| Veterinary inspections | Of each horse, before and after each race. |

| Race season | March to September. Races are scheduled at approximately fortnightly intervals. |

| Number of races | Less than 100 per season. |

| Horses | Thoroughbreds, drawn from flat racing population, must be at least three years old, and may race in both flat and jump races during the jump race season. |

| Tracks | Left handed turf tracks, no steep downhill runs to finishing-lines. |

| Race field | Field sizes are small, with less than 8 horses on average in a race. Low fields are not uncommon (<5 starters). |

| Race start | Starting gates used at commencement of races. |

| Race speed | Races are run on slow tracks (heavy conditions), with heavier weights carried (>64 kg). |

| Hurdle obstacles | Hurdles are padded panels, maximum 1 metre in height, with standardised design. |

| Steeple obstacles | Steeples are a mix of brush top panels and live hedges not less than 1.15 m in height, depending on race course, with height and width specified by regulator. No water jumps or drops. |

2. Methodology

3. Results

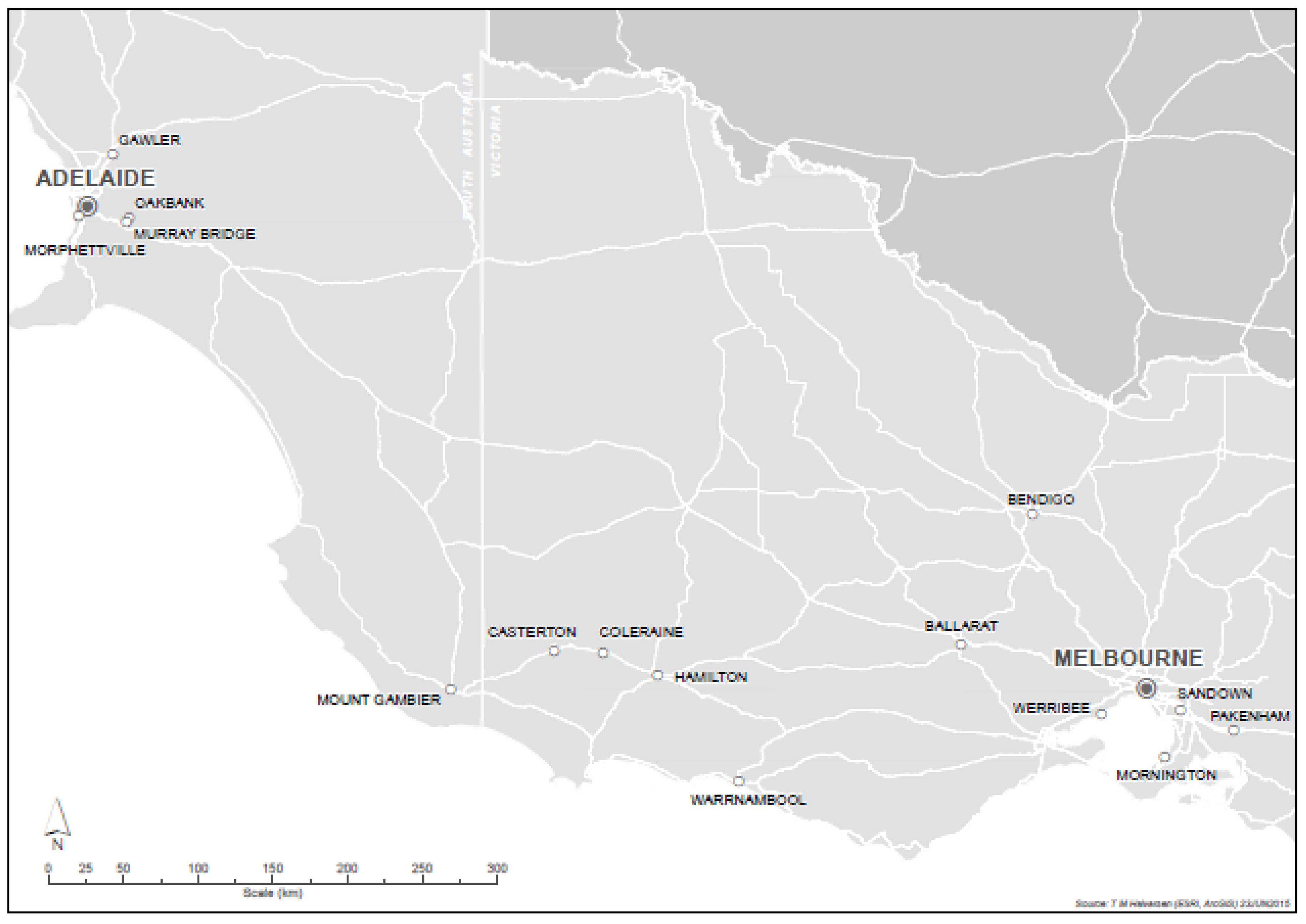

3.1. Location of Australian Jump Racing

3.2. Participants in Australian Jump Racing

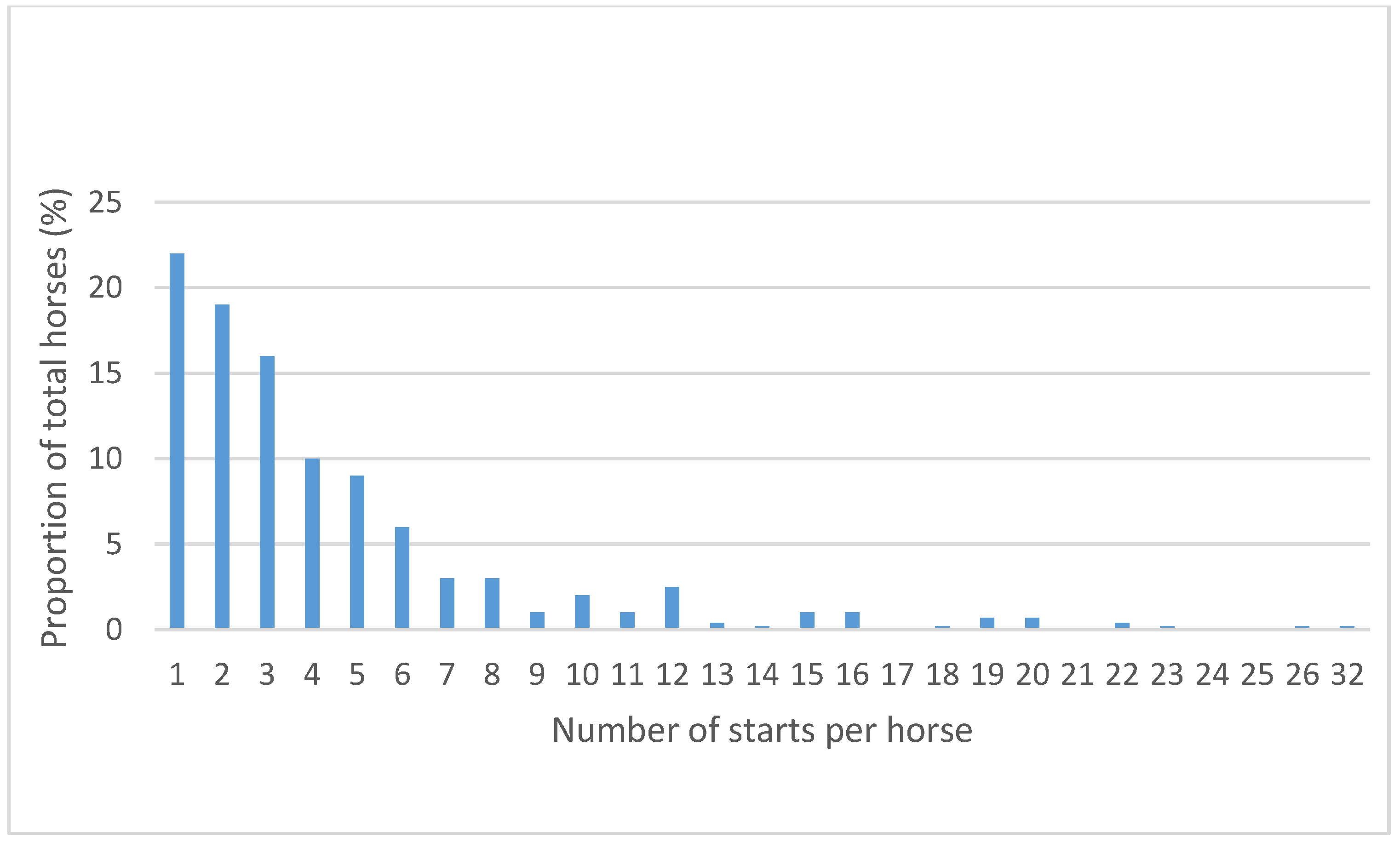

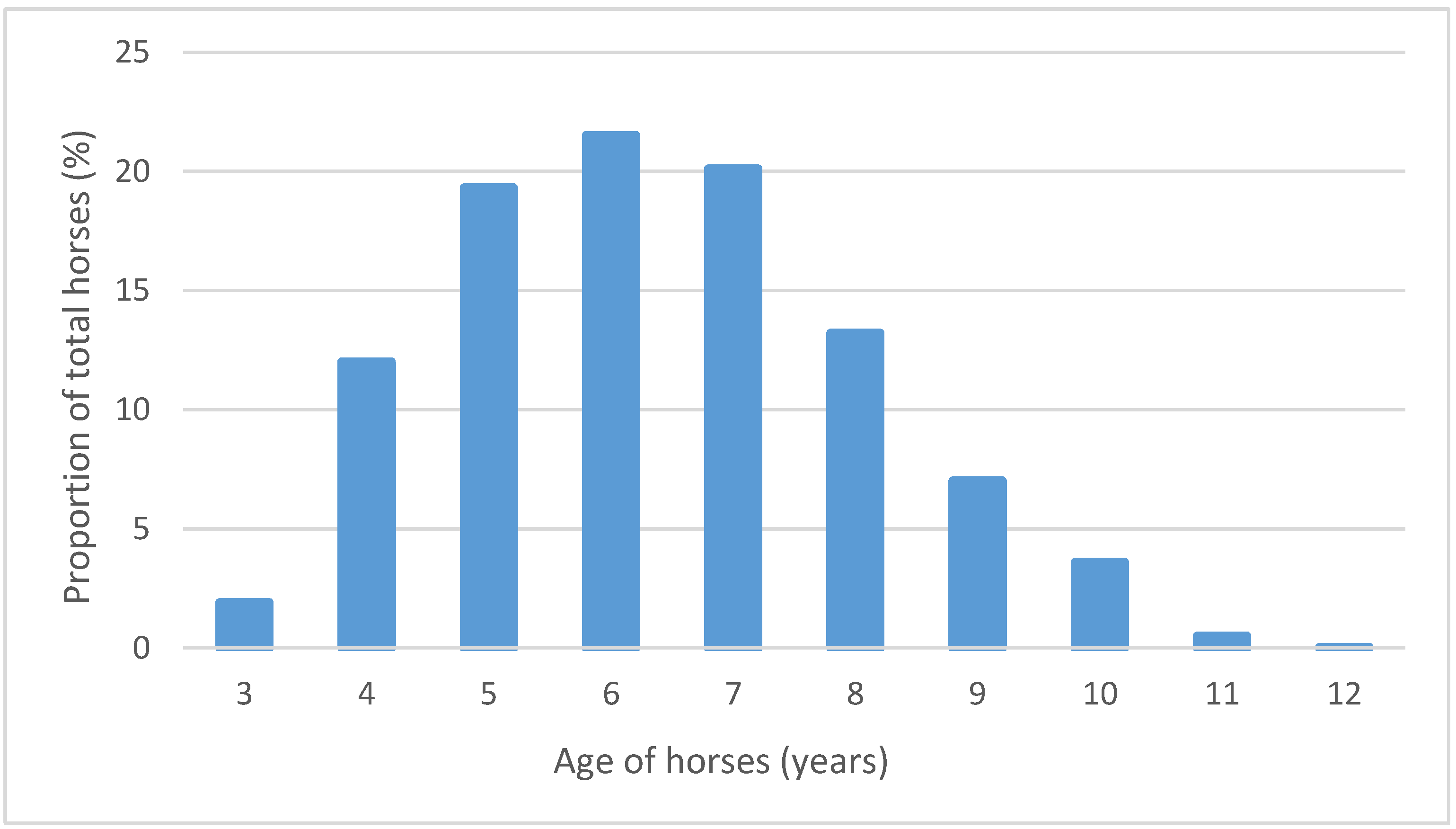

3.2.1. Horses

| Number of Horses 2012 | Number of Horses 2013 | Number of Horses 2014 | Number of Horses 2012 & 2013 | Number of Horses 2012 & 2014 | Number of Horses 2012, 2013 & 2014 | Number of Horses 2012 & 2014 but not 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 176 | 209 | 195 | 65 (37%) | 40 (21%) | 27 (14%) | 13 (7%) |

3.2.2. Trainers

| Trainer Rank | Number of Starts | Proportion of Total Starts (%) | Proportion of Victorian Starts (%) | Proportion of South Australian Starts (%) | Number of Horses Trained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Victoria | |||||

| 1 | 231 | 11.7 | 9.2 | 19.9 | 34 |

| 2 | 136 | 6.9 | 7.7 | 4.4 | 21 |

| 3 | 135 | 6.9 | 7.3 | 5.5 | 24 |

| 4 | 89 | 4.5 | 5.1 | 2.8 | 25 |

| 5 | 79 | 4.0 | 4.8 | 1.5 | 18 |

| South Australia | |||||

| 1 | 67 | 3.5 | 1.0 | 12.1 | 15 |

| 2 | 32 | 1.6 | 0.1 | 6.6 | 3 |

| 3 | 10 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 1.5 | 6 |

| 4 | 7 | 0.3 | n/a | 1.5 | 3 |

| 5 | 7 | 0.3 | n/a | 1.5 | 3 |

| New South Wales | |||||

| 1 | 4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0 | 4 |

| New Zealand | |||||

| 1 | 33 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 5.2 | 12 |

| 2 | 3 | 0.15 | n/a | 0.4 | 2 |

| 3 | 1 | n/a | n/a | 0.2 | 1 |

3.2.3. Jockeys

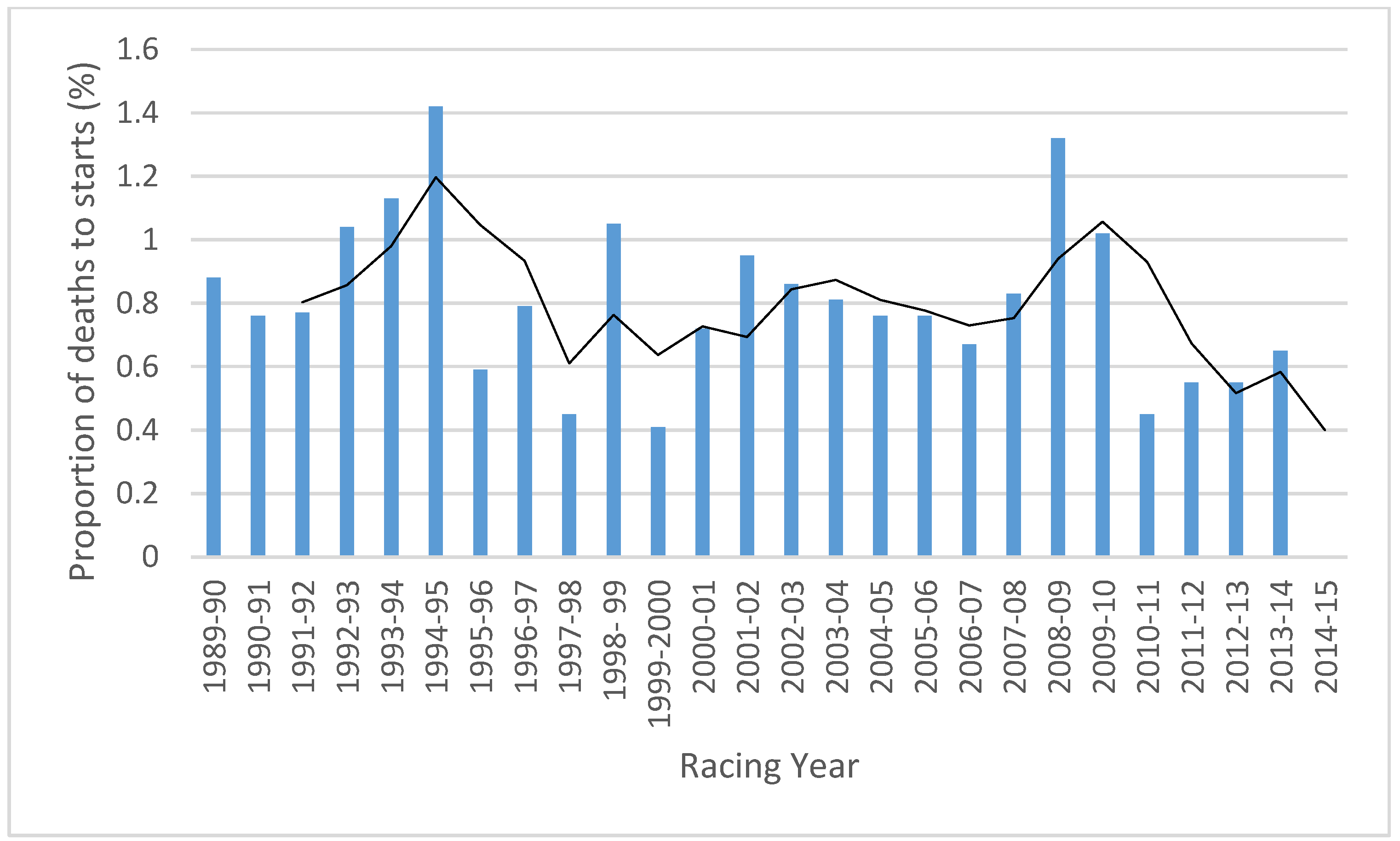

3.3. Horse Falls and Fatalities

| Race Type | Starts | Finishes | Deaths | Fatality Rate (Deaths per 1000 Starts) | Falls | Fall Rate (% of Starts) | Fatalities as Proportion of Falls (%) | FF* | BD** | RO*** | LR**** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hurdle | 1328 | 1135 | 1 | 0.75 | 39 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 128 | 7 | 1 | 18 |

| Steeplechase | 642 | 537 | 9 | 14 | 26 | 4.0 | 35 | 65 | 14 | ||

| Total | 1970 | 1672 | 10 | 5.1 | 65 | 3.3 | 15 | 193 | 7 | 1 | 32 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Risks to Horses in Hurdles and Steeplechases

4.2. Does Jump Racing Extend a Horse’s Racing Career?

4.3. The Future of Jump Racing

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Evans, D.; McGreevy, P. An investigation of racing performance and whip use by jockeys in thoroughbred races. PLoS ONE 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McManus, P.; Montoya, D. Towards new understandings of human-animal relationships in sport: A study of Australian jumps racing. Soc. Cultur. Geogr. 2012, 13, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitchens, P.; Blizzard, C.L.; Jones, G.; Day, L.; Fell, J. Enduring sport: The incidence of race day jockey falls in Australia, 2002–2006. Med. J. Austr. 2009, 190, 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.M.; Marks, F.; Mata, F.; Parkin, T. A case control study to investigate risk factors associated with horse falls in steeplechase races at Cheltenham racetrack. Compar. Exerc. Physiol. 2013, 9, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.M.; Marlin, D.M.; Langley, N.; Parkin, T.D.; Randle, H. The Grand National; A review of factors associated with non-completion and horse-falls, 1990–2012. Compar. Exerc. Physiol. 2013, 9, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, J. Should the Grand National be Banned? 2014. Available online: http://horsetalk.co.nz/2014/should-the-grand-national-be-banned/LZexzz3JbMISd97 (accessed on 26 August 2015).

- Alexander, M. Premier Annointed Patron Saint of Jumps Racing. 2013. Available online: http://www.standard.net.au/story/1474965/premier-anointed-patron-saint-of-jumps-racing/ (accessed on 26 August 2015).

- Yeo, J.-H.; Neo, H. Monkey business: Human-animal conflicts in urban Singapore. Soc. Cultur. Geogr. 2010, 11, 681–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, D.J.; Clark, S.G. The discourses of incidents: Cougars on Mt Elder and in Sabine canyon, Arizona. Policy Sci. 2012, 45, 315–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, P.; Graham, R.; Ruse, K. The construction of human-animal relationships. National jumps day 2013, Te Rapa, Hamilton, NZ. NZ Geogr. 2013, 70, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, P.; Albrecht, G.; Graham, R. The Global Horseracing Industry. Social, Economic, Environmental and Ethical Perspectives; Routledge: Abingdon, VA, USA; New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Vamplew, W. Horses, history and heritage; A comment on the state of going. Austr. Sport. Soc. Histor. Stud. 2008, 23, vii–x. [Google Scholar]

- International Federation of Horse Racing Authorities. Annual Report, 2013. 2013. Available online: http://www.horseracinfed.com/Default.asp?section=Resources&area=2 (accessed on 26 August 2015).

- Franks, T. Animal welfare (Jumps Racing) Amendment Bill. 2015. Available online: http://www.tammyfranks.org.au/?s=jumps+racing (accessed on 25 August 2015).

- Law Society of South Australia. Jumps Racing Submission. 2011. Available online: http://.lawsocietysa.asn.au/LSSA/media/Archived_Submissions.aspx?Websitekey=bf611791-fae7-49b2-884d-cf15580b554e (accessed on 25 August 2015).

- Racing Victoria. Jumps Racing Qualification. 2015. Available online: http://www.rv.racing.com/racing-and-integrity/rules-of-racing (accessed on 26 August 2015).

- Racing Victoria. Rules of Racing. 2015. Available online: http://www.rvracing.com/racing-and-integrity/rules-of-racing (accessed on 25 August 2015).

- Smith, P. Jumps Racing is Dead, Now We Have to Muster the Courage to Bury it. 2009. Available online: http://www.theaustralian.com.au/archive/news/jumps-racing-is-dead/story-e6frg7mo-1225710546646 (accessed on 25 August 2015).

- Racing Victoria. David Jones to Conduct Jumps Review. 2008. Available online: http://racing.co/news/2008-04-09/david-jones-to-conduct-jumps-review (accessed on 26 August 2015).

- Victorian Jumps Races Suspended after More Deaths. 2009. Available online: http://www.smh.com.au/news/sport/horseracing/victorian-jumps-races-suspended-after-more-deaths/2009/05/07/1241289301661.html (accessed on 25 August 2015).

- Animals Australia. Submission to State of Victoria, Members of Parliament, Dec 2008. Available online: http://www.animalsaustralia.org/documents/Jumps-Racing-Submission-to-Victorian-MPs-Dec-2008.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2015).

- Boden, L.; Anderson, J.A.; Charles, K.L.; Morgan, J.M.; Parkin, T.D.H.; Slocombe, R.F.; Clarke, A.F. Risk of fatality and causes of death of thoroughbred horses associated with racing in Victoria, Australia: 1989–2004. Equine Vet. J. 2006, 38, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racing Victoria. Jumps Racing Review 2009 Racing Victoria Limited. 2009. Available online: http://www.rspca.vic.org/issues-take-action/jumps-racing/RSPCA-2009-Racing-Victoria-Limited-review.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2015).

- Racing Victoria. Jumps Racing Decision. 2010. Available online: http://www.racing.com/news/2010-01-2/jumps-racing-decision-january-21 (accessed on 25 August 2015).

- Racing Victoria. Board Decision on Hurdle and Steeplechase Racing. 2010. Available online: http://www.racing.com/news/2010-09-02/board-decision-on-hurdle-and-steeplechase-racing (accessed on 25 August 2015).

- Racing Victoria. One Year Steeplechase Racing Program Approved. 2010. Available online: http://www.racing.com/news/2010-10-07/one-year-steeplechase-racing-program-approved (accessed on 26 August 2015).

- Fortnum, S. Racing Minister Pledges Support for Jumps Racing. 2011. Available online: http://www.races.com.au/2011/04/09/racing-minister-pledges-support-for-jumps-racing (accessed on 26 August 2015).

- Racing Victoria. Jumps Racing Program Released. Available online: http://www.racing.com/news/2011-11-22/jumps-racing-program-released (accessed on 26 August 2015).

- Barnes, J. Brief History of Jumps Racing in Australia. 2015. Available online: http://barnesphotography.com.au/jumps11/page1.htm (accessed on 25 August 2015).

- Bazley, N. Jumps Ban. 2009. Available online: http://www.abc.net.au/btn/story/s2573586.htm (accessed on 30 July 2015).

- RSPCA Victoria. 2014 Another Horse Death Marks Another Day in Jumps Racing: When Will It End? 2015. Available online: http://rspcavic.org/documents/media/Media%/releases/2014/RSPCA-Media-Release-Another-horse-death-marks-another-day-in-jumps-racing.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2015).

- RSPCA South Australia. Jumps Racing. 2015. Available online: http://www.rspca.org/the-issues/jumps-racing/ (accessed on 26 August 2015).

- Coalition for the Protection of Racehorses. Jumps Racing. 2015. Available online: http://www.horseracingkills.com/the-issues/jumps-racing (accessed on 26 August 2015).

- Coalition for the Protection of Racehorses. Deathwatch Report 2014. 2014. Available online: http://www.horseracingkills.com/the-issues/jumps-racing (accessed on 26 August 2015).

- The Humane Society. Jump Racing. 2015. Available online: http://www.hsi.org.au/go/to/567/jumps-racing.html#.VZ8rG10ViUk (accessed on 26 August 2015).

- RSPCA Victoria. Jumps Racing. 2015. Available online: http://www.rspcavic.org/issues-take-action/jumps-racing/ (accessed on 26 August 2015).

- Australian Racing Board. Australian Racing Fact Book 2013/14. 2014. Available online: http://www.australianracingboard.com.au/fact_book.aspx (accessed on 26 August 2015).

- Racing Victoria. RVL Implements Further Jumps Policies. 2008. Available online: http://racing.com/news/2008-08-22/rvl-implements-further-jumps-policies (accessed on 26 August 2015).

- Williams, J.M.; Marks, C.F.; Parkin, T.D.M.; DaMata, F. An epidemiological review of factors that increase the risk of horse falls in steeplechase races at Cheltenham. Compar. Exerc. Physiol. 2013, 9, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinchbeck, G.L.; Clegg, P.D.; Proudman, C.J.; Morgan, K.L.; French, N.P. Case control study to investigate factors for horse falls in hurdle racing in England and Wales. Vet. Rec. 2003, 152, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinchbeck, G.L.; Clegg, P.D.; Proudman, C.J.; Morgan, K.L.; French, N.P. Whip use and race progress are associated with horse falls in hurdle and steeplechase racing in the UK. Equine Vet. J. 2004, 36, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, J.M.; Aldous, N.; Da Mata, F. Factors associated with horse falls in British steeplechase racing from 2008 to 2011. In Proceedings of the 8th International Society of Equitation Science; International Society of Equitation Science: Edinburgh, UK, 2012; p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.M.; Smith, K. Factors associated with horse falls in British class 1 steeplechases 1999 to 2011. In Proceedings of the 8th International Society of Equitation Science; International Society of Equitation Science: Edinburgh, UK, 2012; p. 143. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, M. Bool Brings Hope and Relief to Jumping Fraternity. 2014. Available online: http://www.smh.com.au/sport/horseracing/bool-brings-hope-and-belief-to-jumping-fraternity-20140503-zr3r3.html (accessed on 25 August 2015).

- Auld, T.; Fawkes, A. Jumps Racing Back on Track. 2012. Available online: http://www.standard.net.au/story/370326/jumps-racing-back-on-track/ (accessed on 25 August 2015).

- Pinchbeck, G.L.; Clegg, P.; Proudman, C.; Riggs, C.; Singer, E.R.; Webbon, P.M.; Morgan, K.L. Race and course level risk factors for fatal distal limb fracture in racing Thoroughbreds. Equine Vet. J. 2004, 36, 521–526. [Google Scholar]

- Parkin, T. Epidemiology of training and racing injuries. Equine Vet. J. 2007, 39, 466–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demo for Try Pickle. Available online: http://www.facebook.com/banjumpsracing/event/44562276530/ (accessed on 1 September 2015).

- Jumps Racing: The Week That Never Was. 2014. Available online: http://www.banjumpsracing.com/2014/05 (accessed on 5 April 2015).

- Bailey, C.J.; Hodgson, D.R.; Bourke, J.M. Flat, hurdle and steeple racing; Risk factors for musculoskeletal injury. Equine Vet. J. 1998, 30, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourke, J.M. Fatalities on racecourses in Victoria. A seven year study. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference of Racing Analysts and Veterinarians; R & W Publications: Elma, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 265–268. [Google Scholar]

- Pinchbeck, G.L.; Clegg, P.D.; Proudman, C.J.; Morgan, K.L.; French, N.P. A prospective cohort study to investigate factors for horse falls in UK hurdle and steeplechase racing. Equine Vet. J. 2004, 36, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinchbeck, G.L.; Clegg, P.D.; Proudman, C.J.; Morgan, K.L.; Wood, J.L.; French, N.P. Factors and sources of variation in horse falls in steeplechase racing in the UK. Prev. Vet. Med. 2002, 55, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, T.D.H.; Clegg, P.D.; French, N.P.; Proudman, C.J.; Riggs, C.M.; Singer, E.R.; Webbon, P.M.; Morgan, K.L. Risks for fatal lateral condylar fracture of the third metacarpus/metatarsus in UK racing. Equine Vet. J. 2004, 37, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, B.A.; Hitchens, P.L.; Otarhal, P.; Si, L.; Palmer, A.J. Workplace injuries in thoroughbred racing: An analysis of insurance payments and injuries amongst jockeys in Australia from 2002 to 2010. Animals 2015, 5, 897–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K.; McGreevy, P.; McManus, P. A critical review of horse-related risk: A research agenda for safer mounts, riders and equestrian cultures. Animals 2015, 5, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, D. Eventing in Crisis. 2015. Available online: http://www.horsetalk.co.nz/saferdie/131-eventingincrisis.shtml#ixzz3Xue7tgCh (accessed on 2 July 2015).

- Grand National Deaths at Aintree Fuel Criticism from Animal Rights Groups. Available online: http://www.london24.com/sport/other/grand_national_2013_horse_deaths_at_aintree_fuel_criticism_from_animal_rights_groups (accessed on 5 April 2015).

- O’Sullivan, S. Animals, Equality and Democracy; Palgrave MacMillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- McGinley, S. The Glorious Spectacle of Jumps Racing. 2013. Available online: http://www.theroar.com.au/2013/06/05/the-glorious-spectacle-of-jumps-racing (accessed on 1 September 2015).

- Adams, J. Over the Hurdles; Melbourne Books: Melbourne, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Best, G. Gotta Take Care Rewards Trainers Judgement with Galleywood. 2014. Available online: http://www.smh.com.au/sport/horseracing/gotta-take-care-rewards-trainers-judgment-with-galleywood-20140430-zr219.html (accessed on 25 August 2015).

- Best, G. Let the Fun Times Roll in the Brierly. 2012. Available online: http://www.standard.net.au/story/71258/let-the-fun-times-roll-in-brierly/ (accessed on 25 August 2015).

- Bolwell, C.F.; Rogers, C.W.; Gee, E.K.; Rosanowski, S.M. Descriptive statistics and the pattern of horse racing in New Zealand: Part One Thoroughbred racing. Animal Prod. Sci. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velie, B.D.; Wade, C.M.; Hamilton, N.A. Profiling the careers of thoroughbred horses racing in Australia betwen 2000 and 2010. Equine Vet. J. 2013, 45, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geelen, R. The internet age of misinformation. Breed. Rac. 2014, 117, 52–54. [Google Scholar]

- Auld, T. Bumper Results for May Racing Carnival. 2015. Available online: http://www.standard.net.au/story/3074625/bumper-results-for-may-racing-carnival/ (accessed on 25 August 2015).

- Auld, T. Napthine Hails Valediction Win a Success for Jumps Racing. 2014. Available online: http://www.standard.net.au/story/2213088/napthine-hails-valediction-win-a-success-for-jumps-racing/ (accessed on 25 August 2015).

- Stephens, T. Motion to Establish a Joint Committee on Jumps Racing. 2015. Available online: http://www.terrystephens.com.au/news/Speeches/ID/164/Motion-To-Establish-a-Joint-Committee-on-Jumps-Racing (accessed on 1 September 2015).

- Carlyon, C. D-Day for Jumps. After a Brutal Backlash, the Carnival could be Over; Herald Sun: Melbourne, Australia, 2009; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Paluka Visit a Jump Ahead. 2015. Available online: http://www.standard.net.au/story/3145927/pakula-visit-a-jump-ahead/ (accessed on 25 August 2015).

- Auld, T. Prizemoney Boost as Races Transferred to Warrnambool. 2015. Available online: http://www.standard.net.au/story/3051460/prizemoney-boost-as-races-transferred-to-warrnambool/ (accessed on 25 August 2015).

- Racing Victoria to Transfer Grand Nationals from Sandown. 2015. Available online: http://www.smh.com.au/sport/horseracing/racing-victoria-to-transfer-grand-nationals-from-sandown-20150427-1muins.html (accessed on 19 October 2015).

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruse, K.; Davison, A.; Bridle, K. Jump Horse Safety: Reconciling Public Debate and Australian Thoroughbred Jump Racing Data, 2012–2014. Animals 2015, 5, 1072-1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani5040399

Ruse K, Davison A, Bridle K. Jump Horse Safety: Reconciling Public Debate and Australian Thoroughbred Jump Racing Data, 2012–2014. Animals. 2015; 5(4):1072-1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani5040399

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuse, Karen, Aidan Davison, and Kerry Bridle. 2015. "Jump Horse Safety: Reconciling Public Debate and Australian Thoroughbred Jump Racing Data, 2012–2014" Animals 5, no. 4: 1072-1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani5040399

APA StyleRuse, K., Davison, A., & Bridle, K. (2015). Jump Horse Safety: Reconciling Public Debate and Australian Thoroughbred Jump Racing Data, 2012–2014. Animals, 5(4), 1072-1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani5040399