Refining Housing, Husbandry and Care for Animals Used in Studies Involving Biotelemetry

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Housing, Husbandry and Care Issues Associated With Biotelemetry

2.1. Group Housing

- (1)

- The ‘buddy’ system, in which an instrumented animal is group housed with one or more uninstrumented individuals [20,21]. The fate of the buddy (or buddies) can be planned for in advance. Potential options are: (i) rehoming; (ii) use in another study, provided that the animals are suitable (e.g., of an appropriate age); or (iii) humane killing at the end of the study. Both options (i) and (ii) may involve changing established groups, in which case advice from animal technologists or the attending veterinarian can help to reduce stress to the animals. Option (iii) is an ethical issue, although it need not be an animal welfare issue if the killing technique is properly refined. The animals’ tissues or organs should be used in other studies or for training purposes where appropriate, or facilities may sell surplus, euthanased animals for use as food for rehabilitated wildlife, raptors or ‘exotic’ companion animals. Some establishments have set up programmes in which surplus animals can be certified fit and rehomed to responsible carers [22,23] and there is a legal framework to support rehoming in many countries, provided that it is in the animal’s best interests [7].

- (2)

- Devices that can be switched on and off with a magnetically actuated system in situ, i.e., following implantation, and used one at a time in pair- or group-housed animals. This avoids the issue of deciding fates for ‘ex-buddies’, provided that recording data sequentially is compatible with the scientific protocol, or can be compensated for by the experimental design. Switching devices on and off can also extend battery life, thus facilitating reduction in animal numbers because more data can be gathered from each animal (but see Section 2.3 below).

- (3)

- Instrumenting all animals, and then separating them for data recording sessions only. This allows data to be recorded at the same time from different individuals, but periods of social isolation (and being moved to a different enclosure, if applicable) will be highly stressful for some animals, with implications for welfare and data quality [20,21]. The suitability of this approach will depend upon factors such as the species, duration of isolation and whether animals can habituate to the protocol.

- (4)

- Use of data logging devices instead of transmitters, where data are recorded onto a microchip and downloaded once the device has been retrieved from the animal. Data can be retrieved following each session if external loggers are used, but there will clearly be a longer wait in the case of implanted loggers. Also, device failure may not be detected until the download is attempted, meaning that studies would have to be repeated.

- The pair or group was well-established and stable before surgery. If groups are stable before surgery, there is a greater chance of achieving harmonious regrouping afterwards. Drawing pairs or groups from littermates is an obvious option, which should be possible whether animals are bred either in-house or externally. Good liaison with the breeder will be necessary if animals are sourced from outside the establishment (liaison with any external breeding facilities to ensure consistency in housing and care conditions is also good practice, although if there are differences then the aim should be to ‘level up’ and implement the better husbandry protocols at both).

- If animals have undergone transport to the facility, they have had an adequate settling-in period to enable both recovery from any transport stress and acclimatisation to environmental changes and new caretakers. Absolute minimum settling-in periods before surgery have been suggested of a week for rodents, two weeks for dogs, and a month for non-human primates [6]. Note that animals should be allowed a minimum post-implantation recovery period of two weeks before conducting further procedures [20,21].

- Animals have recovered from anaesthesia so that they are capable of interacting appropriately with others.

- Wound closure has been fully refined, for example by the use of intradermal sutures [24]. This, together with effective pain management and careful asepsis, will stop animals paying excessive attention to their own wounds, reducing the risk of drawing the attention of others via visual or olfactory cues.

- Housing and care are also refined, including the provision of sufficient space and enrichment, which will shift animals’ attention from their own and others’ wounds and allow them to retreat from one another [6].

- There is adequate supervision from carers in the initial regrouping period, and for as long as is necessary to ensure that there is no persistent discomfort or pain. Behavioural assessments should also check that animals are interacting in an acceptable way, e.g., hierarchies are appropriate and there is no bullying [5,25].

If single housing really is unavoidable for justifiable scientific reasons, animals should not undergo implantation surgery unless they are able to tolerate being housed on their own. A trial period should be set up to assess how well animals can adapt before moving on with the study.

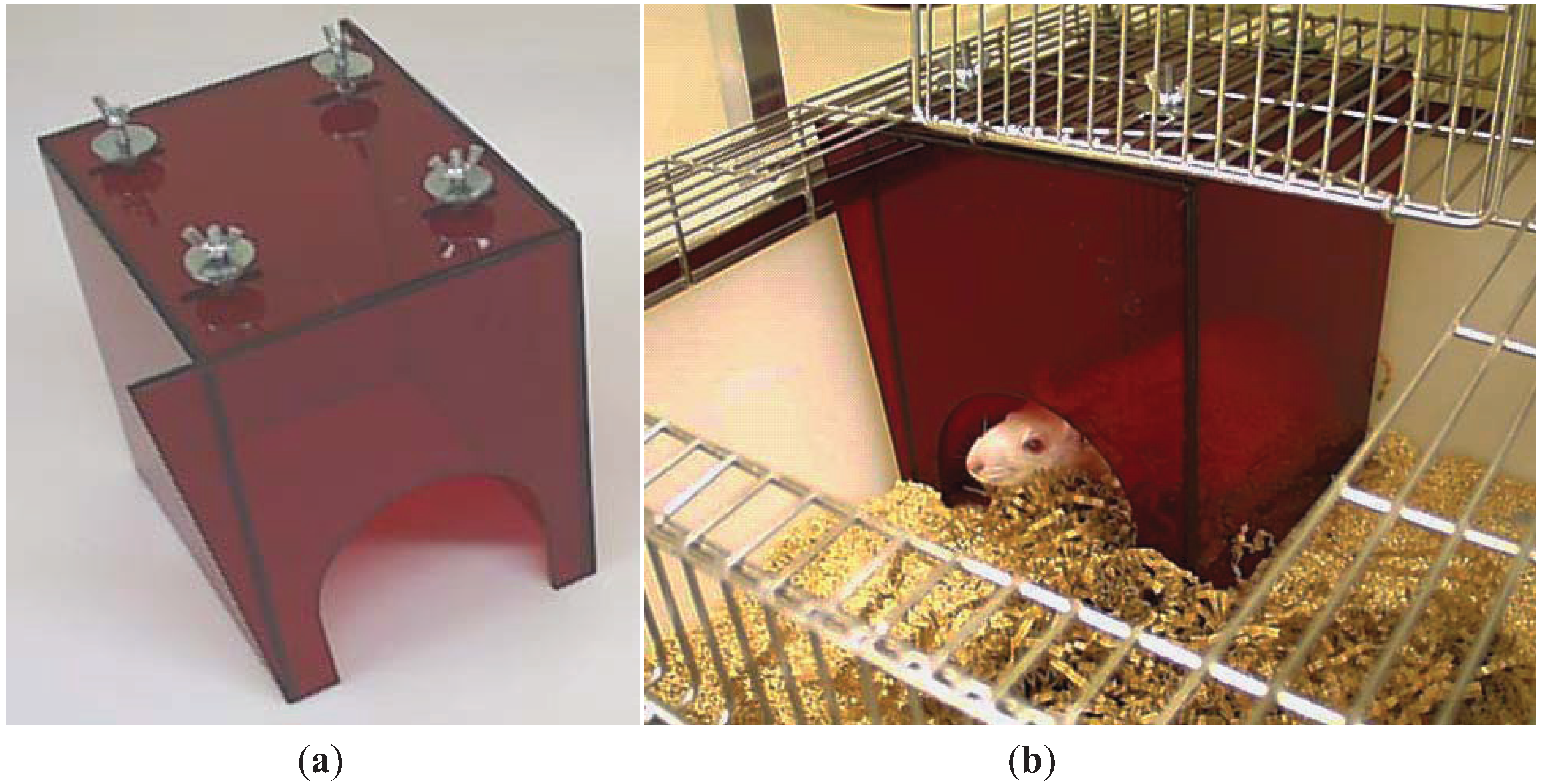

2.2. Providing Environmental Enrichment

2.3. Long Term Housing in the Laboratory and Reuse

2.4. Using Telemetered Physiological or Behavioural Data to Help Assess Wellbeing

- using telemetered data to help determine humane endpoints;

- reusing implanted animals in welfare studies, e.g., to provide physiological correlates with behaviour;

- using telemetered data to assess stress due to restraint and transport;

- comparing responses to different housing, enrichments and interactions with humans;

- monitoring recovery from surgery using telemetered data; and

- using physiological data to help compare the effectiveness of different analgesic agents.

3. Recommendations

- Recognise that although biotelemetry can facilitate reduction and refinement, the technique has the potential to cause suffering—it is a ‘refinement that needs refining’. There is a need to apply a harm-benefit assessment to procedures involving biotelemetry and to ensure that these are fully refined.

- Keep up to date with technical developments such as wider availability of multi-frequency devices and smaller implants. If there are unmet technological needs that could help to refine the use of biotelemetry (e.g., multi-frequency, implantable devices for mice), communicate with device manufacturers to make them aware of the demand.

- Ensure that surgical procedures are conducted according to current good practice with respect to the competence of the surgeon, surgical approach, welfare assessment, pain management, wound closure and asepsis.

- Provide group housing for social animals used in biotelemetry studies as the default; ensure that animals are only singly housed if there is sound scientific or veterinary justification.

- If periods of single housing are unavoidable during data collection, keep these to a minimum and monitor animals carefully during reintroductions.

- Provide environmental enrichment as the default, thinking creatively about alternative approaches if some items would not be appropriate.

- Critically consider the pros and cons of automated observation systems that necessitate single housing, taking the welfare and scientific implications into account.

- Set a limit for maximum duration of laboratory housing for long term studies, with clear criteria for behavioural assessments and humane endpoints. Seek advice on this from the attending veterinarian, experienced animal technologists, and/or local ethics, animal care and use committee or animal welfare body as appropriate.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dictionary and Thesaurus – Merriam-Webster Online. Available online: http://www.merriam-webster.com/ (accessed on 13 December 2013).

- Sarazan, R.D.; Schweitz, K.T.R. Standing on the shoulders of giants: Dean Franklin and his remarkable contributions to physiological measurements in animals. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2009, 33, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenwis, J.E. Recent advances in telemetry promote further progress in reduction and refinement. NC3Rs Invited Articles, 2010. Available online: http://www.nc3rs.org.uk/news.asp?id=16 (accessed on 13 December 2013).

- Anonymous. ICHS7A Safety Pharmacology Studies for Human Pharmaceuticals. 2000. Available online: http://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Safety/S7A/Step4/S7A_Guideline.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2013).

- Morton, D.B.; Hawkins, P.; Bevan, R.; Heath, K.; Kirkwood, J.; Pearce, P.; Scott, L.; Whelan, G.; Webb, A. Refinements in telemetry procedures: Seventh report of the BVA(AWF)/FRAME/ RSPCA/UFAW Joint Working Group on Refinement, Part A. Lab. Anim. 2003, 37, 261–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, P.; Morton, D.B.; Bevan, R.; Heath, K.; Kirkwood, J.; Pearce, P.; Scott, L.; Whelan, G.; Webb, A. Husbandry refinements for rats, mice, dogs and non-human primates used in telemetry procedures: Seventh report of the BVA(AWF)/FRAME/RSPCA/UFAW Joint Working Group on Refinement, Part B. Lab. Anim. 2004, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on the Protection of Animals used for Scientific Purposes. Off. J. Eur. Union 2010, L 276, 33–79. [Google Scholar]

- Guiding Principles for Preparing for Undertaking Aseptic Surgery. A Report by the LASA Education, Training and Ethics Section. Jennings, M.; Berdoy, M. (Eds.) Laboratory Animal Science Association (LASA): Tamworth, UK, 2010; Available online: http://www.lasa.co.uk/publications.html (accessed on 13 December 2013).

- van der Staay, F.J.; Arndt, S.S.; Nordquist, R.E. Evaluation of animal models of neurobehavioral disorders. Behav. Brain. Funct. 2009, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilkenny, C.; Parsons, N.; Kadyszewski, E.; Festing, M.F.W.; Cuthill, I.C.; Fry, D.; Hutton, J.; Altman, D.G. Survey of the quality of experimental design, statistical analysis and reporting of research using animals. PLoS ONE 2009, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Worp, H.B.; Howells, D.W.; Sena, E.S.; Porritt, M.J.; Rewell, S.; O’Collins, V.; Macleod, M.R. Can animal models of disease reliably inform human studies? PLoS Med. 2010, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Editorial Staff of Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. Animal Models: Their Value in Predicting Drug Efficacy and Toxicity; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; Volume 1245. [Google Scholar]

- CAMARADES. Why is CAMARADES Needed? 2011. Available online: http://www.camarades.info/ index_files/Why%20CAMARADES.htm (accessed on 29 January 2014).

- Hawkins, P. Facts and demonstrations: Exploring the effects of enrichment on data quality. The Enrichment Record 2014, 12–21. Available online: http://enrichmentrecord.com/current-issue/ (accessed on 18 February 2014). [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th ed.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, C.; Canal, J.R.; Domínguez, E.; Campillo, J.E.; Guillén, M.; Torres, M.D. Individual housing influences certain biochemical parameters in the rat. Lab. Anim. 1997, 31, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Späni, D.; Arras, M.; König, B.; Rülicke, T. Higher heart rate of laboratory mice housed individually vs in pairs. Lab. Anim. 2003, 37, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verwer, C.M.; van der Ven, L.T.M.; van den Bos, R.; Hendriksen, C.F.M. Effects of housing condition on experimental outcome in a reproduction toxicity study. Reg. Tox. Pharmacol. 2007, 48, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karelina, K.; Norman, G.J.; Zhang, N.; Morris, J.S.; Peng, H.; DeVries, A.C. Social isolation alters neuroinflammatory response to stroke. PNAS 2009, 106, 5895–5900. [Google Scholar]

- Meijer, M.K.; Kramer, K.; Remie, R.; Spruijt, B.M.; van Zutphen, L.F.M.; Baumans, V. Effect of routine procedures on physiological parameters in mice kept under different husbandry procedures. Anim. Welf. 2006, 15, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Meijer, M.K.; Sommer, R.; Spruijt, B.M.; van Zutphen, L.F.M. Influence of environmental enrichment and handling on the acute stress response in individually housed mice. Lab. Anim. 2007, 41, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laboratory Animal Science Association (LASA). Laboratory Animal Science Association Guidance on the Rehoming of Laboratory Dogs. A Report Based on a LASA Working Party and LASA Meeting on Rehoming Laboratory Animals; Jennings, M., Howard, B., Eds.; LASA: Tamworth, UK, 2004; Available online: http://www.lasa.co.uk/publications.html (accessed on 13 December 2013).

- Hawkins, P.; Hubrecht, R.; Buckwell, A.; Cubitt, S.; Howard, B.; Jackson, A. Refining Rabbit Care: A Resource for Those Working With Rabbits in Research; RSPCA: Southwater, UK, 2008. Available online: http://www.rspca.org.uk/researchrabbits (accessed on 13 December 2013).

- Wolfensohn, S.; Lloyd, M. Introduction to surgery and surgical techniques. In Handbook of Laboratory Animal Management and Welfare, 4th ed.; Wolfensohn, S., Lloyd, M., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, P.; Morton, D.B.; Burman, O.; Dennison, N.; Honess, P.; Jennings, M.; Lane, S.; Middleton, V.; Roughan, J.V.; Wells, S.; Westwood, K. A guide to defining and implementing protocols for the welfare assessment of laboratory animals: Eleventh report of the BVA(AWF)/FRAME/RSPCA/UFAW Joint Working Group on Refinement. Lab. Anim. 2011, 45, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaman, S.C. Laboratory Rabbit Housing: An Investigation of the Social and Physical Environment. A Summary of the Report to the UFAW Pharmaceutical Housing and Husbandry Steering Committee (PHHSC), Based on a Ph.D. Thesis, 2002. Available online: http://www.ufaw.org.uk/pdf/phhsc-schol1-summary.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2013).

- Buchanan-Smith, H. Marmosets and tamarins. In The UFAW Handbook on the Care and Management of Laboratory and Other Research Animals, 8th ed.; Hubrecht, R., Kirkwood, J., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2010; pp. 543–563. [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur Clark, J.; Pomeroy, C.J. The laboratory dog. In The UFAW Handbook on the Care and Management of Laboratory and Other Research Animals, 8th ed.; Hubrecht, R., Kirkwood, J., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2010; pp. 432–452. [Google Scholar]

- Van Loo, P.L.P.; Kuin, N.; Sommer, R.; Avsaroglu, H.; Pham, T.; Baumans, V. Impact of ‘living apart together’ on postoperative recovery of mice compared with social and individual housing. Lab. Anim. 2007, 41, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masneuf, S.; University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland. Personal observations. 2011.

- LASA/RSPCA. Guiding Principles on Good Practice for Ethical Review Processes, 2nd ed. 2010. Available online: http://www.lasa.co.uk/publications.html (accessed on 13 December 2013).

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Hawkins, P. Refining Housing, Husbandry and Care for Animals Used in Studies Involving Biotelemetry. Animals 2014, 4, 361-373. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani4020361

Hawkins P. Refining Housing, Husbandry and Care for Animals Used in Studies Involving Biotelemetry. Animals. 2014; 4(2):361-373. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani4020361

Chicago/Turabian StyleHawkins, Penny. 2014. "Refining Housing, Husbandry and Care for Animals Used in Studies Involving Biotelemetry" Animals 4, no. 2: 361-373. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani4020361

APA StyleHawkins, P. (2014). Refining Housing, Husbandry and Care for Animals Used in Studies Involving Biotelemetry. Animals, 4(2), 361-373. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani4020361