1. Introduction

Tapertail anchovy (

Coilia nasus), commonly known as knife fish, phoenix tail fish, or hair flower fish, belongs to the order Clupeiformes, family Engraulidae, and genus

Coilia. This species is predominantly found in the northwestern and western Pacific Ocean. In China,

C. nasus is widely distributed across the Yellow Sea, Bohai Sea, East China Sea, and in various connected rivers and lakes, such as the Yangtze River, Yellow River, Liao River, and Qiantang River. It is considered a common small-to-medium-sized commercial fish in China [

1]. Historically,

C. nasus was abundant in terms of resources and catch, with its flesh—known for its tender texture and high fat content—being highly prized. It was even regarded as one of the “Three Delicacies of the Yangtze River”. Threatened by overexploitation and habitat loss in the early 21st century, the population of

C. nasus has declined significantly [

2]. As a result,

C. nasus has been listed on the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species [

3].

In recent years, with the implementation of national policies such as the “Yangtze River Protection Law” and the “10-Year Fishing Ban on the Yangtze River” catches of wild

C. nasus have been prohibited. As a result, the demand for

C. nasus is mainly met through aquaculture. Due to the high price of wild-caught

C. nasus, illegal fishing still occurs. The emergence of traceability technologies has helped regulate and ensure the authenticity of these products. However, current assessments of the genetic structure and diversity of wild and farmed populations are limited, and research on seafood traceability is still in its infancy in China [

4]. As a result, pinpointing and tracing the origin of

C. nasus from the Yangtze River has become a critical issue that must be addressed.

Research on the genetic diversity of

C. nasus has only been initiated in recent decades. Cheng et al. [

5] analyzed the genetic polymorphism and genetic relationships of

C. nasus species using mitochondrial cytochrome b gene fragments as molecular markers. Additionally, Yang et al. [

6] used the full sequence of the mitochondrial control region as molecular markers to analyze the genetic structure of

C. nasus populations in the Yangtze River estuary and adjacent areas. However, there is a notable degree of genetic differentiation among different populations of

C. nasus. These findings suggest that the resources of

C. nasus have been compromised, and its genetic pool has diminished, highlighting the urgent need for enhanced conservation efforts and further research. The genetic structure and diversity of a population serve as the theoretical foundation and crucial reference for the rational development and sustainable utilization of its resources.

C. nasus is widely distributed and has formed numerous geographic populations. Due to environmental changes and adaptation to different habitats, these geographic populations exhibit variations. However, the extent of differences between these populations remains poorly understood, and research on traceability technologies is scarce.

Microsatellite DNA is one of the most important molecular markers currently used to construct genetic maps. There are linked relationships between genes, and some genes can form linkage groups that can be independently separated from other linkage groups. Researchers can obtain the order and relative distance of individual genes on the chromosomes based on the genetic distances between them, and localize multiple genes directly on the chromosomes, thus constituting a physical map. Zhang et al. [

7] constructed a high-density linkage map using 164 female

Epinephelus fuscoguttatus and their female parents Currently, microsatellite markers have been successfully applied in parentage identification across various species [

8]. This method, particularly in forensic science, is considered one of the most accurate techniques for individual identification and parentage testing. It has also been widely used in marine species. Zhang et al. [

9] studied the relationship between the accuracy of microsatellite-based parentage identification, the identification ability, and the size of the candidate parent population in Hucho taimen, revealing that the identification ability decreased as the size of the candidate parent population increased. Yang et al. [

10] used 11 pairs of developed microsatellite primers to tag parents and established a systematic evaluation method of “tagging parents—release and re-capture—paternity identification”, with high identification accuracy.

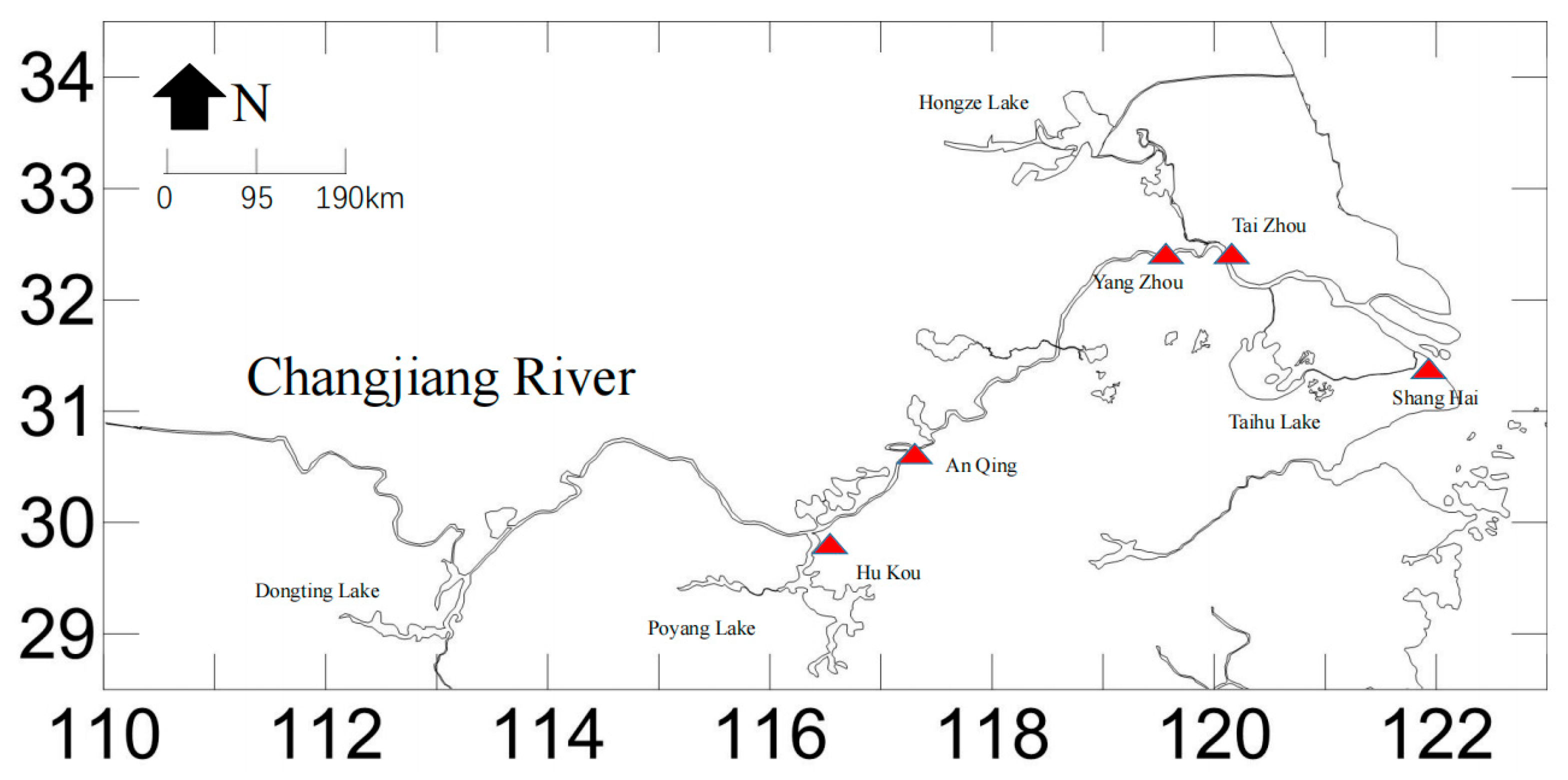

Therefore, in this study, a systematic analysis of C. nasus population was carried out through microsatellite markers, and the discriminant function was constructed using microsatellite data. The objective was to analyze the population construction of C. nasus from the genetic diversity level, population genetic structure and population discrimination perspectives. This will help to promote the conservation of C. nasus germplasm resources and accurately locate the origin of C. nasus at the molecular level, which will help people to protect wild C. nasus.

4. Discussion

Microsatellite markers have become a popular tool for detecting genetic variation in aquatic species due to their co-occurrence, ease of detection, high polymorphism, stability, and minimal DNA quality requirements. In the present study, 18 microsatellite loci were chosen to investigate the genetic diversity and structure of four wild populations and one breeding population of C. nasus. The analysis revealed average values of 20.567 for Na, 13.506 for Ne, and high polymorphism with PIC averaging 0.919, indicating strong genetic diversity. All 21 microsatellite loci had PIC values exceeding 0.5, confirming their high polymorphism. These markers are suitable for assessing genetic diversity in C. nasus populations and can be applied in selection and breeding programs. The results from this study will provide valuable data for monitoring genetic variation in C. nasus populations.

Na,

Ne, I,

Ho,

He, and PIC are key parameters used to assess the genetic diversity of a population, and they are all positively correlated with it. It is generally believed that the closer

Na is to the absolute value of

Ne indicates that the population alleles are more evenly distributed and have higher genetic diversity [

14]. In the current study,

Na was found to be greater than

Ne in all five populations of

C. nasus, indicating that the alleles were unevenly distributed across these populations. This pattern has also been observed in species like cipangopaludina chinensis [

14] and macrobrachium rosenbergii [

15]. The index I reflects both the genetic richness and evenness of a population [

16]. For instance, the average I-value of nine populations of tachypleus tridentatus was 1.39, indicating high genetic diversity in these populations [

17]. In the case of cipangopaludina chinensis, I-values ranged from 0.412 to 1.226, also showing significant genetic diversity [

14]. In this study, the I-values of the five

C. nasus populations ranged from 2.626 to 2.794, with an average of 2.743, reflecting high genetic diversity in all five populations. While

Ho can provide insight into genetic diversity,

He is less influenced by sample size and is therefore often considered a more reliable measure of population diversity [

18]. A higher

He value generally indicates greater genetic diversity. For example,

He values for 14 populations of pelteobagrus fulvidraco ranged from 0.358 to 0.749, suggesting high genetic diversity [

19]. In this study, the

He values for the five populations of

C. nasus ranged from 0.903 to 0.931, indicating high genetic diversity across all populations. Furthermore, when

He exceeds

Ho, as seen in nine populations in a prior study, it suggests the potential presence of heterozygous deletions, possibly due to rare genotypes, dummy alleles, artificial selection, or inbreeding [

20]. Similar patterns were observed in the study of six cyprinus carpio populations by Dong et al. [

21]. The inbreeding coefficient within population (

Fis) is a core parameter in population genetics for quantifying the level of inbreeding among individuals within a population. In the present study, the

Fis values of the

C. nasus populations ranged from 0.1 to 0.3, indicating a mild level of inbreeding with a slight deficit of heterozygotes, which exerted a negligible impact on the genetic composition of the populations. This pattern could be attributed to the anadromous migratory behavior of

C. nasus: annual migrations facilitate genetic exchange among different geographic populations, thereby mitigating the degree of inbreeding within individual populations.

A

FST value of less than 0.05 indicates a low level of genetic differentiation between populations, while values between 0.05 and 0.15 suggest moderate differentiation, and values between 0.15 and 0.25 indicate a high level of differentiation [

19]. In the present study, the

FST values ranged from 0.2898 to 0.5714, indicating a low level of genetic differentiation among most populations. Notably, the

FST values between the HK population with the SH, AQ and YZ populations were all greater than 0.05, which demonstrated a moderate degree of genetic differentiation between the Hukou population and the aforementioned populations (

p < 0.01). This phenomenon could be attributed to the fact that the HK population inhabits Poyang Lake permanently, leading to limited genetic exchange with other populations. In contrast, the remaining populations undertake migratory reproduction along the Yangtze River, thus facilitating relatively frequent genetic communication. Gene flow plays a key role in maintaining low genetic differentiation between populations. Generally, if

Nm is less than 1, it suggests potential genetic segregation, while

Nm more than 1 means genetic differentiation is not significant, and

Nm more than 4 indicates very minimal differentiation [

22]. In this study, all populations had

Nm values more than 4 (ranging from 6.449 to 10.858), which indicates frequent gene flow between populations and low genetic differentiation. The

C. nasus is a migratory fish species, and their migration route is from the Yellow Sea to the mouth of the Yangtze River in Shanghai, and then upstream along the main channel of the Yangtze River. We collected samples along this route. Most

C. nasus are migratory, but there are also some that stay in large lakes along the way, and the annual migration season promotes their genetic exchange [

23]. The AMOVA analysis revealed that 4% of the genetic variation came from differences within populations, 23% from differences between individuals, and 73% from differences within individuals. This also supports the conclusion that genetic differentiation among the five populations of

C. nasus is low. The standardized genetic distances, calculated using Nei’s method, reflect the degree of genetic differentiation, while the genetic similarity coefficients show the relatedness between populations, with the two being inversely proportional [

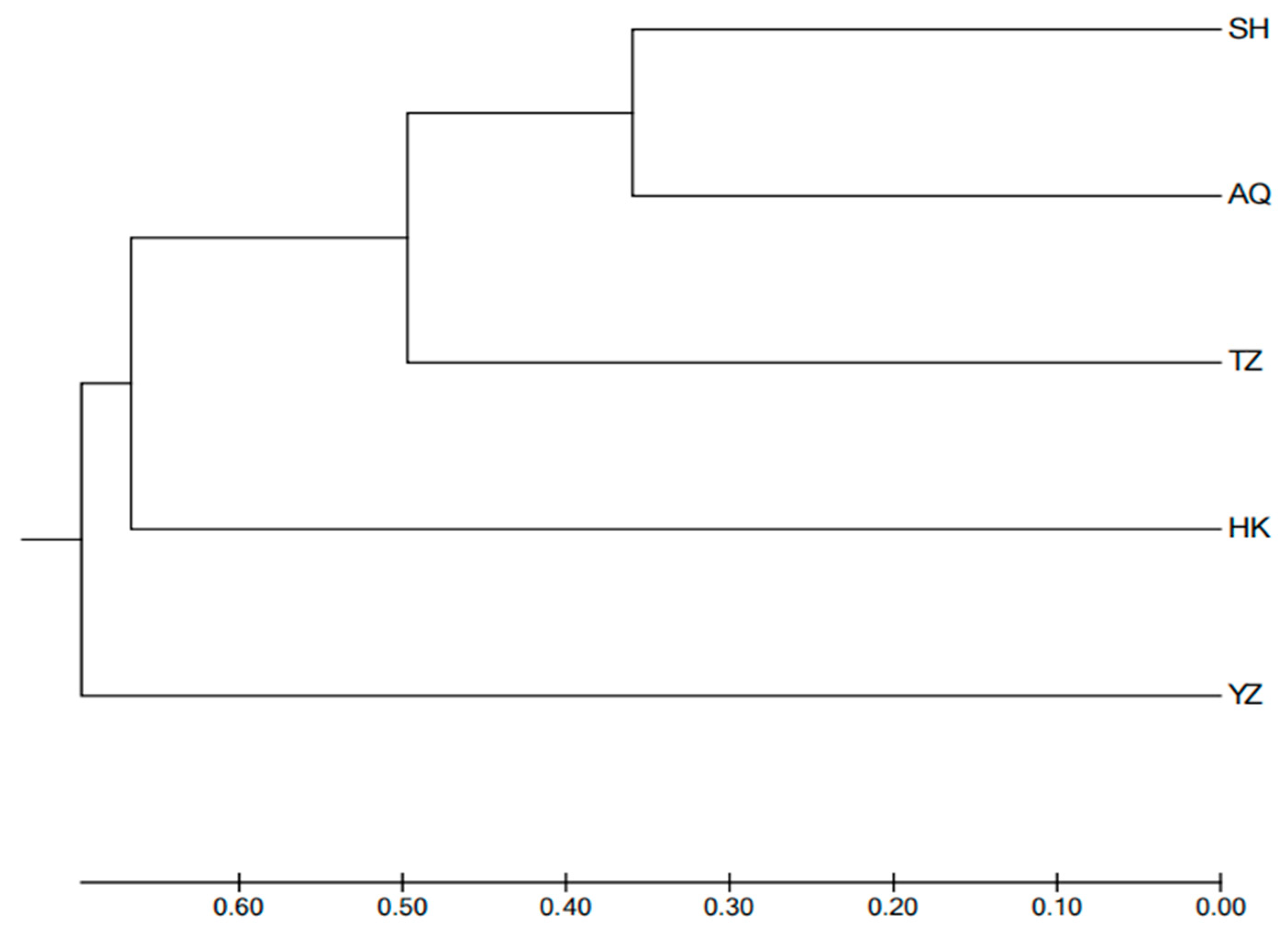

24]. In this study, genetic distances between populations ranged from 0.719 to 1.898, with similarity coefficients varying between 0.150 and 0.487. The SH and AQ populations were the most genetically similar, with the smallest genetic distance (0.719) and highest similarity coefficient (0.487). In contrast, the YZ population had larger genetic distances from other populations (1.056 to 1.898) and lower similarity coefficients (0.150 to 0.348), reflecting its distinctness from the other populations. This could also be due to other groups being wild populations. According to the UPGMA clustering tree based on Nei’s genetic distance, the SH group clustered first with the AQ group, then with the TZ group, followed by the HK group, and finally the YZ group. Similarly, the PCoA results showed that the SH and AQ groups clustered together, while the YZ group was distinct.

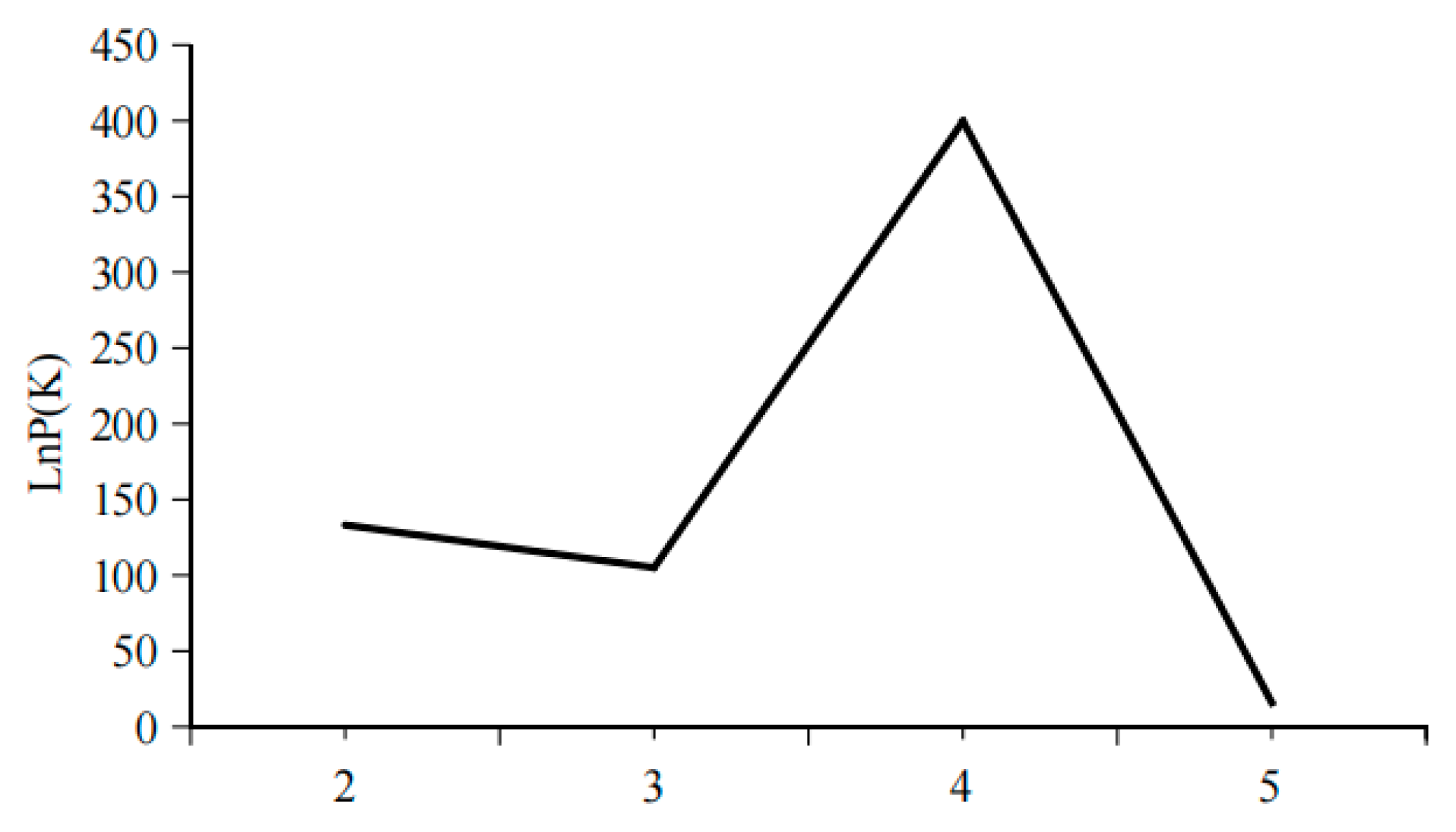

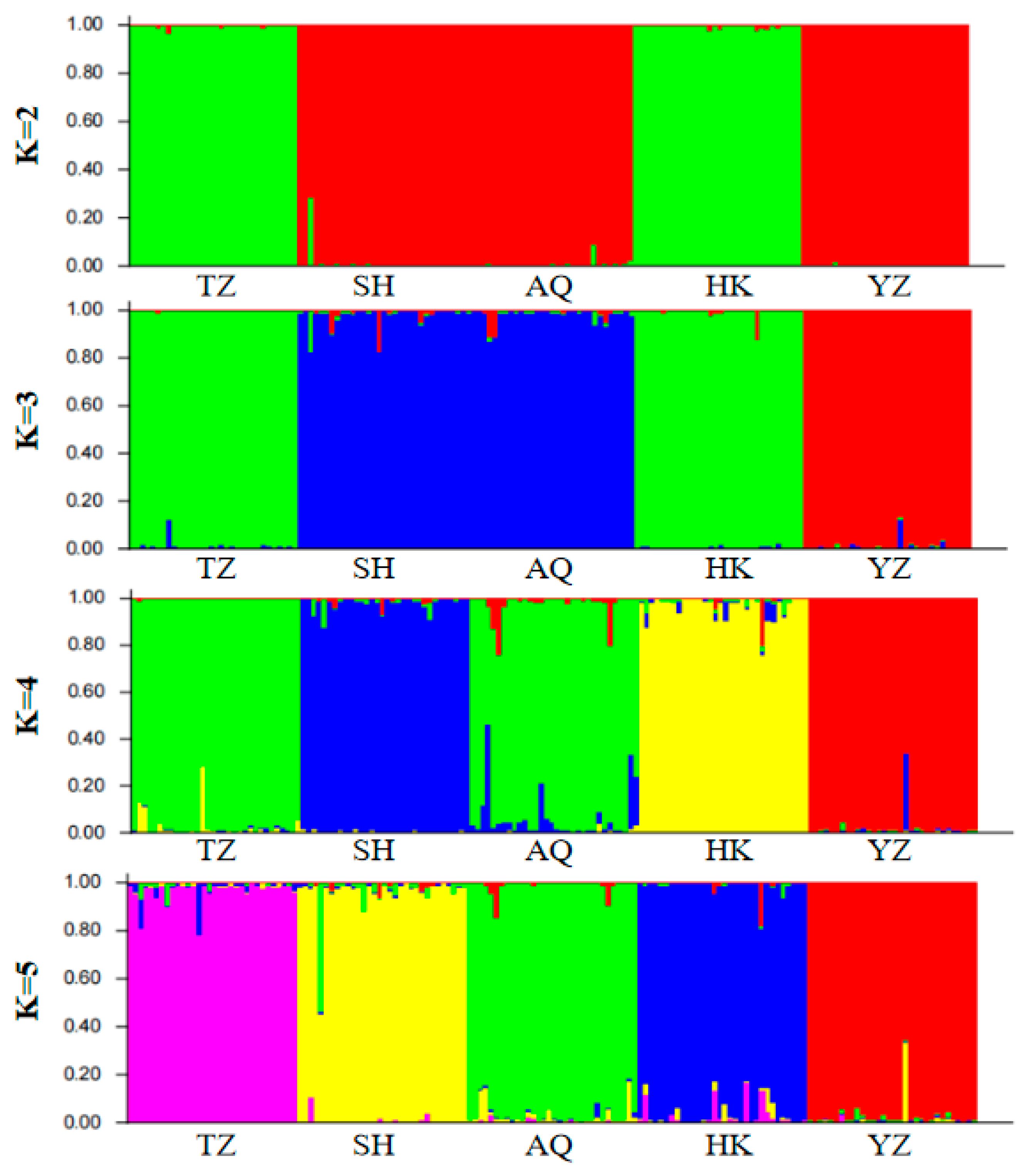

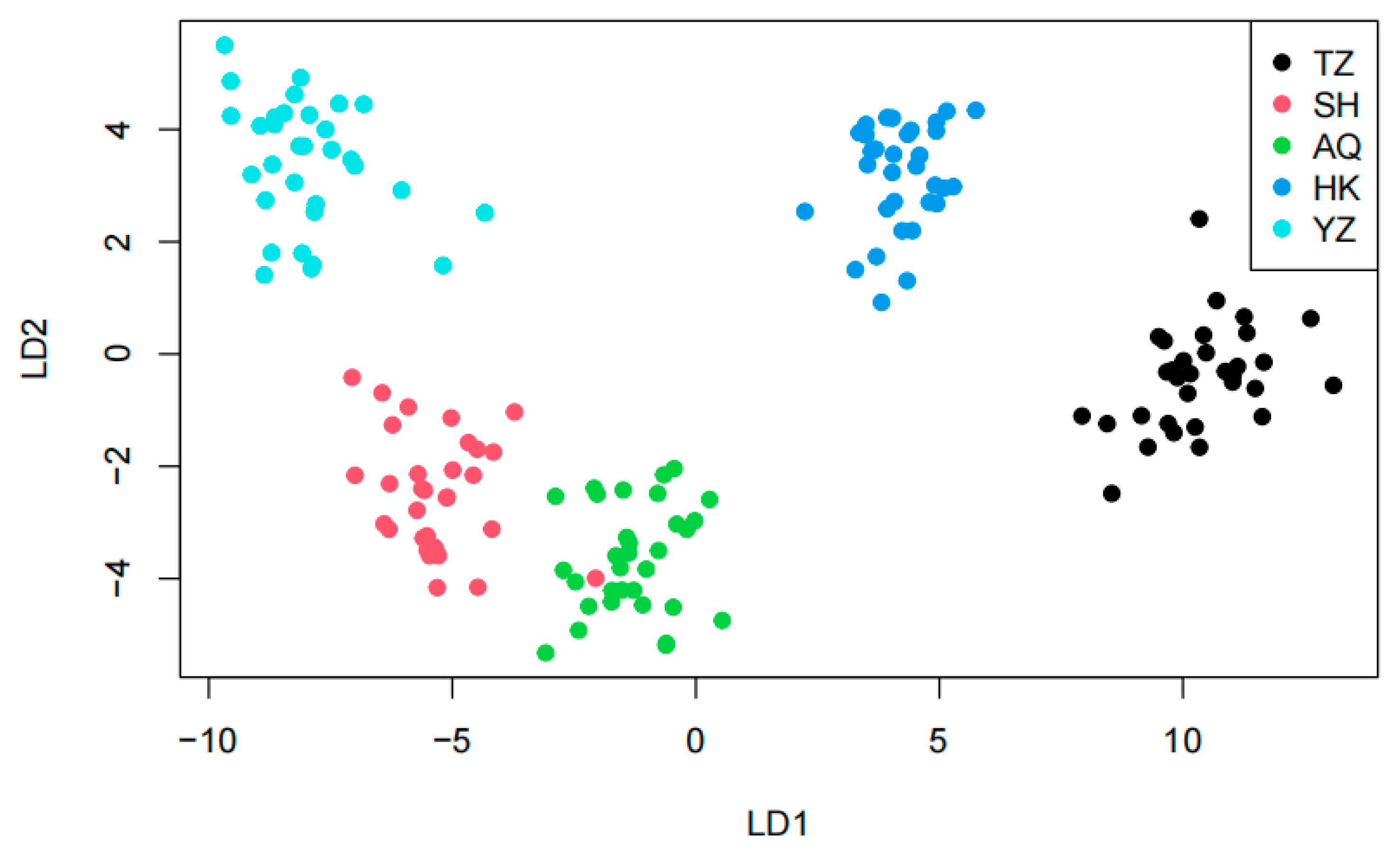

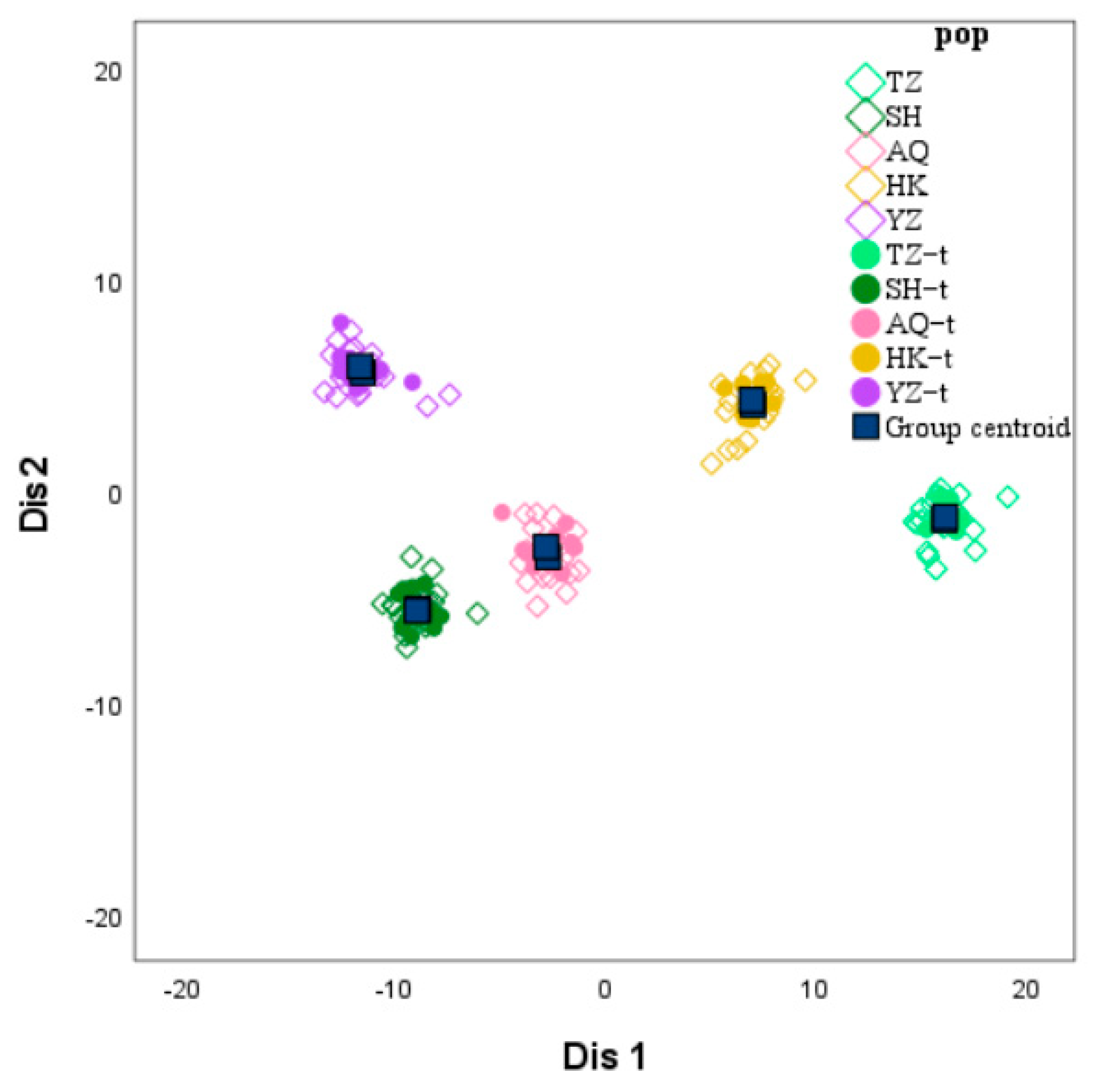

Structure is considered an ideal method for analyzing population genetic structure, as its computational process does not require prior knowledge of the genetic background of the populations. In this study, K values ranging from 2 to 5 were selected, with the number of repetitions set to twenty. The trends of K values and the mean of the related statistic Var[LnP(K)] were analyzed (

Figure 3). A clear inflection point was detected at K = 3, indicating that the optimal estimated number of theoretical populations is three. Examination of the structure plots for different K values (primarily at K = 3) revealed that the genetic structures of SH and AQ are relatively close, while those of TZ and HK are also similar. In contrast, the genetic structure of YZ is distinctly distant from the other four populations, with only a small number of individuals exhibit cross mixing. From a geographical perspective, SH and AQ are both located along the main channel of the Yangtze River, while TZ and HK are situated at the confluence of Poyang Lake and Hongze Lake with the Yangtze River, respectively. YZ represents an artificially cultured population. Their geographical distribution is consistent with the genetic structure inferred by Structure analysis. DAPC does not rely on assumptions of Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium or linkage equilibrium and can provide a robust, model-free assessment of population structure. As shown in

Figure 5, individuals from SH and AQ exhibit some degree of overlap, whereas populations TZ and HK are closely clustered. The YZ population is clearly separated from the other four populations, with no observed individual-level admixture. The inclusion of DAPC strengthens the inference of genetic clustering and validates that the division of

C. nasus populations into three genetic groups is biologically meaningful.

To investigate the population structure of

C. nasus, Xu et al. [

25] employed landmark-based geometric morphometric analysis to quantify otolith morphological characteristics and demonstrated efficacy in distinguishing

C. nasus across distinct aquatic habitats from the Yangtze River. Otolith microchemistry also can be a good way to clearly determined the habitats of

C. nasus [

26]. In addition, muscle mineral elements can be used to determine fish habitat [

27]. In the current study, we adopted a molecular-level approach utilizing microsatellite markers to differentiate

C. nasus populations from various geographical locations. Studies have shown that SNP markers can be used to genetically discriminate fish populations. RA Del [

28] used SNP markers for population genetic analysis of farmed mussels, and more than 90% of the individuals were successfully localized to their place of origin; Zhang et al. [

29] used microsatellite DNA analysis to determine the origin of 190 farmed escaped Atlantic salmon. In our study, the results demonstrated 100% classification accuracy, indicating that this molecular approach effectively identifies the geographical origins of

C. nasus and provides a reliable method for provenance determination. This method enables market regulatory authorities to effectively trace the geographic origin of wild

C. nasus, thereby helping to reduce illegal fishing activities.