The Large Variability in Response to Future Climate and Land-Use Changes Among Large- and Medium-Sized Terrestrial Mammals in the Giant Panda Range

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Species Occurrence Data

2.2. Current and Future Climate and Land-Use Variables

2.3. Species Distribution Modelling

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Model Performance and Variable Importance

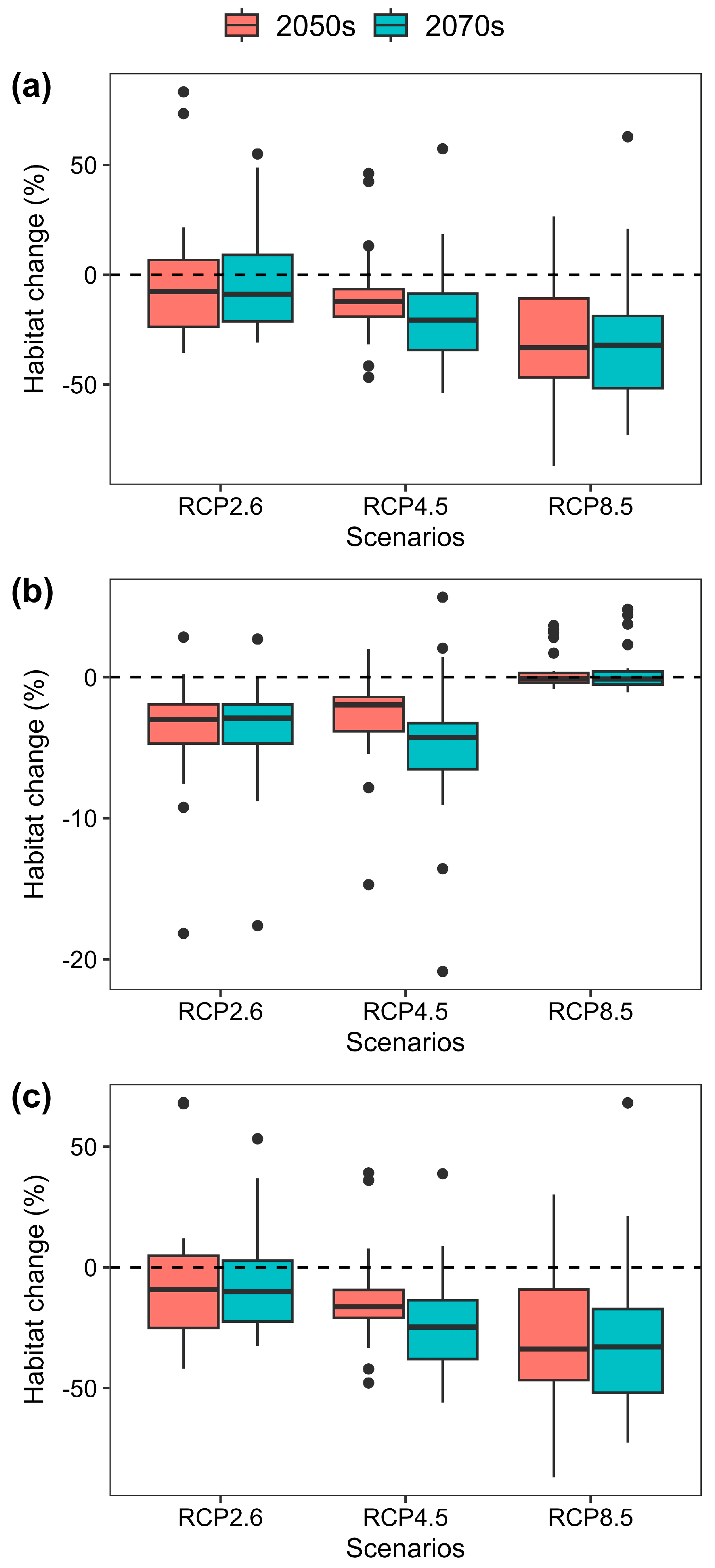

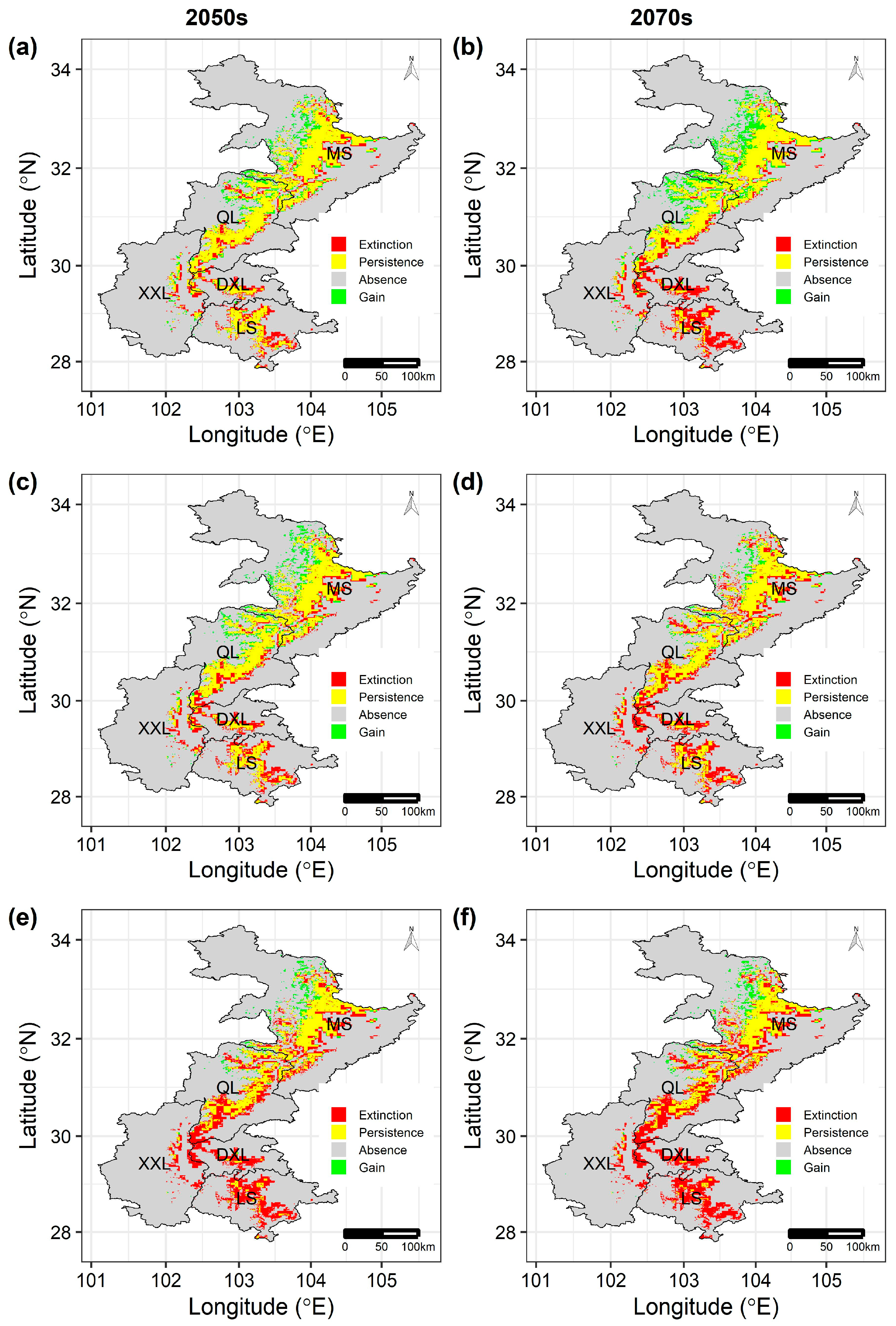

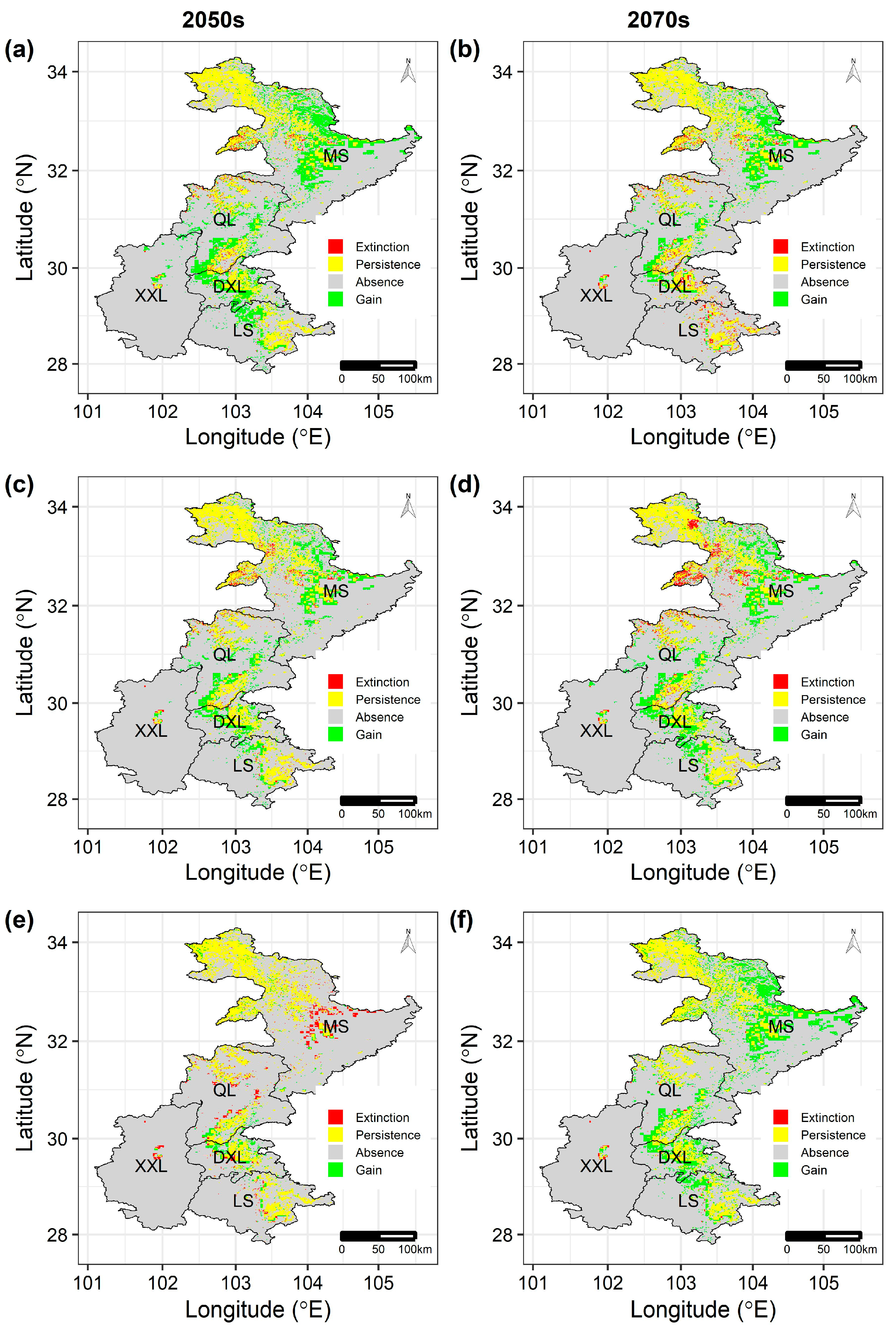

3.2. The Isolated Effect of Climate and Land Use on Habitat Suitability

3.3. The Modulating Effect of Land-Use Change Within Climate Scenarios

3.4. Focus on One Representative and One Atypical Species

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ceballos, G.; Ehrlich Paul, R.; Barnosky Anthony, D.; García, A.; Pringle Robert, M.; Palmer Todd, M. Accelerated modern human–induced species losses: Entering the sixth mass extinction. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1400253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, O.E.; Stuart, C.F.; Armesto, J.J.; Berlow, E.; Bloomfield, J.; Dirzo, R.; Huber-Sanwald, E.; Huenneke, L.F.; Jackson, R.B.; Kinzig, A.; et al. Global biodiversity scenarios for the year 2100. Science 2000, 287, 1770–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Febbraro, M.; Menchetti, M.; Russo, D.; Ancillotto, L.; Aloise, G.; Roscioni, F.; Preatoni, D.G.; Loy, A.; Martinoli, A.; Bertolino, S.; et al. Integrating climate and land-use change scenarios in modelling the future spread of invasive squirrels in Italy. Divers. Distrib. 2019, 25, 644–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiens, J.A.; Stralberg, D.; Jongsomjit, D.; Howell, C.A.; Snyder, M.A. Niches, models, and climate change: Assessing the assumptions and uncertainties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 19729–19736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.B.; Alagador, D.; Cabeza, M.; Nogués-Bravo, D.; Thuiller, W. Climate change threatens European conservation areas. Ecol. Lett. 2011, 14, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, T.H.; Gillings, S.; Pearce-Higgins, J.W.; Brereton, T.; Crick, H.Q.P.; Duffield, S.J.; Morecroft, M.D.; Roy, D.B. Large extents of intensive land use limit community reorganization during climate warming. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 23, 2272–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecl, G.T.; Araújo, M.B.; Bell, J.D.; Blanchard, J.; Bonebrake, T.C.; Chen, I.C.; Clark, T.D.; Colwell, R.K.; Danielsen, F.; Evengård, B.; et al. Biodiversity redistribution under climate change: Impacts on ecosystems and human well-being. Science 2017, 355, eaai9214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestele, R.; Brown, C.; Polce, C.; Maes, J.; Whitehorn, P. Large variability in response to projected climate and land-use changes among European bumblebee species. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 4530–4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Zhao, X. Large variability in response to future climate and land-use changes among Chinese Theaceae species. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12, e9480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radinger, J.; Hölker, F.; Horký, P.; Slavík, O.; Dendoncker, N.; Wolter, C. Synergistic and antagonistic interactions of future land use and climate change on river fish assemblages. Glob. Change Biol. 2016, 22, 1505–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yu, L.; Sohl, T.; Clinton, N.; Li, W.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, X.; Gong, P. A cellular-automata downscaling based 1 km global land use datasets (2010–2100). Sci. Bull. 2016, 61, 1651–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Swaisgood, R.R.; Owen, M.A.; Zhao, X.; Wei, W.; Hong, M.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Z. Assessing the effectiveness of protected areas for panda conservation under future climate and land use change scenarios. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 342, 118319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares-Filho, B.; Moutinho, P.; Nepstad, D.; Anderson, A.; Rodrigues, H.; Garcia, R.; Dietzsch, L.; Merry, F.; Bowman, M.; Hissa, L.; et al. Role of Brazilian Amazon protected areas in climate change mitigation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 10821–10826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, C.R.; Bittick, S.J.; Fong, P. Simultaneous synergist, antagonistic and additive interactions between multiple local stressors all degrade algal turf communities on coral reefs. J. Ecol. 2017, 106, 13901400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Zhuo, Y.; Xu, W.; Kessler, M.; Wang, M.; Yang, W. Synergistic effects of climate and land use change on khulan (Equus hemionus hemionus) habitat in China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 54, e03181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L.Q.; Thong, V.D.; Son, N.T.; Tu, V.T.; Tuan, T.A.; Luong, N.T.; Vy, N.T.; Thanh, H.T.; Huang, J.C.-C.; Csorba, G.; et al. Potential individual and interactive effects of climate and land-cover changes on bats and implications for conservation planning: A case study in Vietnam. Biodivers. Conserv. 2023, 32, 4481–4508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opdam, P.; Wascher, D. Climate change meets habitat fragmentation: Linking landscape and biogeographical scale level in research and conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2004, 117, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, L.; Biesmeijer, J.C.; Rasmont, P.; Vereecken, N.J.; Dvorak, L.; Fitzpatrick, U.; Francis, F.; Neumayer, J.; Ødegaard, F.; Paukkunen, J.P.T.; et al. The interplay of climate and land use change affects the distribution of EU bumblebees. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Forestry Administration. The Third National Survey Report on Giant Panda in China; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- State Forestry Administration. The Fourth National Survey Report on Giant Panda in China; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, X.; Wei, W.; Hong, M.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z. The fate of giant panda and its sympatric mammals under future climate change. Biol. Conserv. 2022, 274, 109715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Pan, S.; Che, Q.; Wei, W.; Zhao, X.; Tang, J. Impacts of climate change on the distributions and diversity of the giant panda with its sympatric mammalian species. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 144, 109452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fick, S.E.; Hijmans, R.J. WorldClim 2: New 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Anderson, R.P.; Schapire, R.E. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol. Model. 2006, 190, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.B.; New, M. Ensemble forecasting of species distributions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007, 22, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Newell, G.; White, M. On the selection of thresholds for predicting species occurrence with presence-only data. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 6, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Huang, J.; Guo, H.; Du, S. Projecting species loss and turnover under climate change for 111 Chinese tree species. Forest Ecol. Manag. 2020, 477, 118488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Préau, C.; Bertrand, R.; Sellier, Y.; Grandjean, F.; Isselin-Nondedeu, F. Climate change would prevail over land use change in shaping the future distribution of Triturus marmoratus in France. Anim. Conserv. 2022, 25, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Order | Common Name | Scientific Name | Number of Records | Training AUC | Test AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primates | Sichuan Snub-Nosed Monkey | Rhinopithecus roxellana | 191 | 0.914 ± 0.004 | 0.912 ± 0.002 |

| Rhesus Macaque | Macaca mulatta | 47 | 0.923 ± 0.008 | 0.917 ± 0.005 | |

| Tibetan Macaque | Macaca thibetana | 306 | 0.822 ± 0.019 | 0.766 ± 0.031 | |

| Carnivora | Asiatic Black Bear | Ursus thibetanus | 537 | 0.909 ± 0.006 | 0.905 ± 0.004 |

| Grey Wolf | Canis lupus | 19 | 0.903 ± 0.060 | 0.797 ± 0.075 | |

| Red Fox | Vulpes vulpes | 29 | 0.872 ± 0.010 | 0.862 ± 0.007 | |

| Giant Panda | Ailuropoda melanoleuca | 2075 | 0.834 ± 0.051 | 0.692 ± 0.085 | |

| Chinese Red Panda | Ailurus fulgens | 632 | 0.826 ± 0.015 | 0.824 ± 0.005 | |

| Hog Badger | Arctonyx albogularis | 149 | 0.830 ± 0.032 | 0.783 ± 0.014 | |

| Masked Palm Civet | Paguma larvata | 28 | 0.771 ± 0.058 | 0.715 ± 0.045 | |

| Asiatic Golden Cat | Catopuma temminckii | 23 | 0.891 ± 0.013 | 0.880 ± 0.011 | |

| Leopard Cat | Prionailurus bengalensis | 522 | 0.862 ± 0.084 | 0.756 ± 0.081 | |

| Artiodactyla | Forest Musk Deer | Moschus berezovskii | 290 | 0.865 ± 0.014 | 0.841 ± 0.008 |

| Tufted Deer | Elaphodus cephalophus | 786 | 0.827 ± 0.027 | 0.788 ± 0.023 | |

| Sambar Deer | Rusa unicolor | 271 | 0.898 ± 0.006 | 0.894 ± 0.003 | |

| Reeves’ Muntjac | Muntiacus reevesi | 78 | 0.780 ± 0.082 | 0.648 ± 0.105 | |

| Takin | Budorcas taxicolor | 1535 | 0.813 ± 0.014 | 0.796 ± 0.010 | |

| Chinese Serow | Capricornis sumatraensis | 914 | 0.918 ± 0.019 | 0.910 ± 0.009 | |

| Chinese Goral | Naemorhedus griseus | 1289 | 0.879 ± 0.024 | 0.833 ± 0.031 | |

| Wild Boar | Sus scrofa | 1385 | 0.941 ± 0.012 | 0.927 ± 0.009 | |

| Rodentia | Chinese Bamboo Rat | Rhizomys sinensis | 73 | 0.831 ± 0.008 | 0.823 ± 0.007 |

| Malayan Porcupine | Hystrix brachyura | 117 | 0.844 ± 0.015 | 0.836 ± 0.010 | |

| Himalayan Marmot | Marmota himalayana | 18 | 0.841 ± 0.046 | 0.777 ± 0.056 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhao, X.; Tang, J.; Xu, H.; Yu, H.; Wei, W.; Zhang, Z. The Large Variability in Response to Future Climate and Land-Use Changes Among Large- and Medium-Sized Terrestrial Mammals in the Giant Panda Range. Animals 2026, 16, 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16030420

Zhao X, Tang J, Xu H, Yu H, Wei W, Zhang Z. The Large Variability in Response to Future Climate and Land-Use Changes Among Large- and Medium-Sized Terrestrial Mammals in the Giant Panda Range. Animals. 2026; 16(3):420. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16030420

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Xuzhe, Junfeng Tang, Hongxia Xu, Huiliang Yu, Wei Wei, and Zejun Zhang. 2026. "The Large Variability in Response to Future Climate and Land-Use Changes Among Large- and Medium-Sized Terrestrial Mammals in the Giant Panda Range" Animals 16, no. 3: 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16030420

APA StyleZhao, X., Tang, J., Xu, H., Yu, H., Wei, W., & Zhang, Z. (2026). The Large Variability in Response to Future Climate and Land-Use Changes Among Large- and Medium-Sized Terrestrial Mammals in the Giant Panda Range. Animals, 16(3), 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16030420