Approaching Standardization of Bovine Ovarian Cortex Cryopreservation: Impact of Cryopreservation Protocols and Tissue Size on Preantral Follicle Population

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection and Processing of Ovarian Tissue

2.2. Slow Freezing and Thawing Protocols

2.3. Vitrification and Warming Protocols

2.3.1. Vitrification-Warming Protocol 1

- I.

- 5 min in 5 mL of vitrification 1—solution 1 (VT1-S1): HS + 5% DMSO + 5% ethylene glycol (EG) + 0.125 M sucrose.

- II.

- 5 min in 5 mL of vitrification 1—solution 2 (VT1-S2): HS + 10% DMSO + 10% EG + 0.25 M sucrose.

- III.

- 2 min in 5 mL of vitrification 1—solution 3: HS + 20% DMSO + 20% EG + 0.5 M sucrose.

2.3.2. Vitrification-Warming Protocol 2

- I.

- 25 min in 5 mL of vitrification 2—solution 1 (VT2-S1): HS + 7.5% DMSO + 7.5% EG + 0.15 M sucrose.

- II.

- 15 min in 5 mL of vitrification 2—solution 2 (VT2-S2): HS + 20% DMSO + 20% EG + 0.5 M sucrose.

2.4. Histological Evaluation

2.5. Immunohistochemistry Analysis for Ki67

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Fragment Size on Preantral Follicular Morphology and Distribution

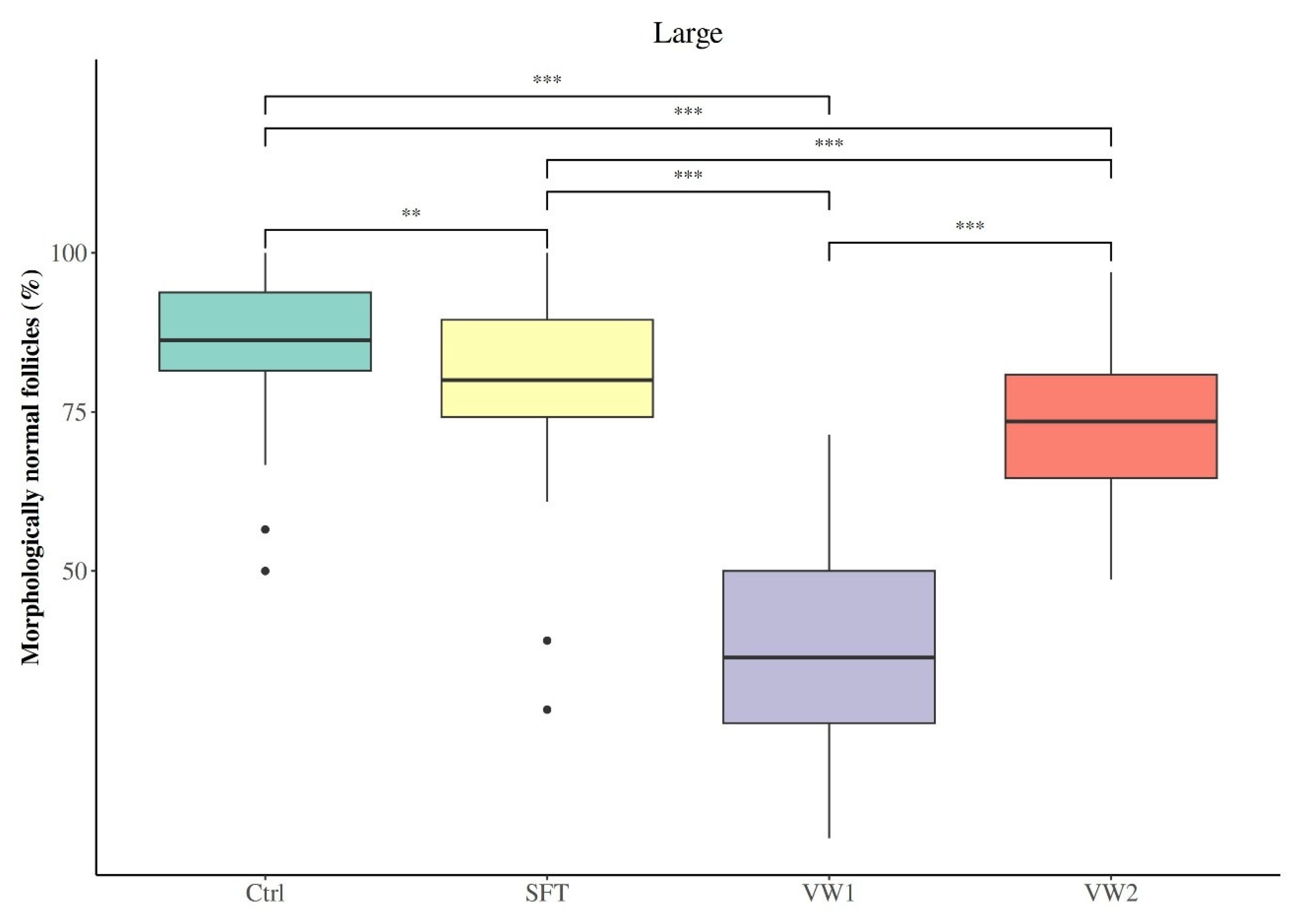

3.2. Effect of Cryopreservation Procedure on Preantral Follicular Morphology and Distribution

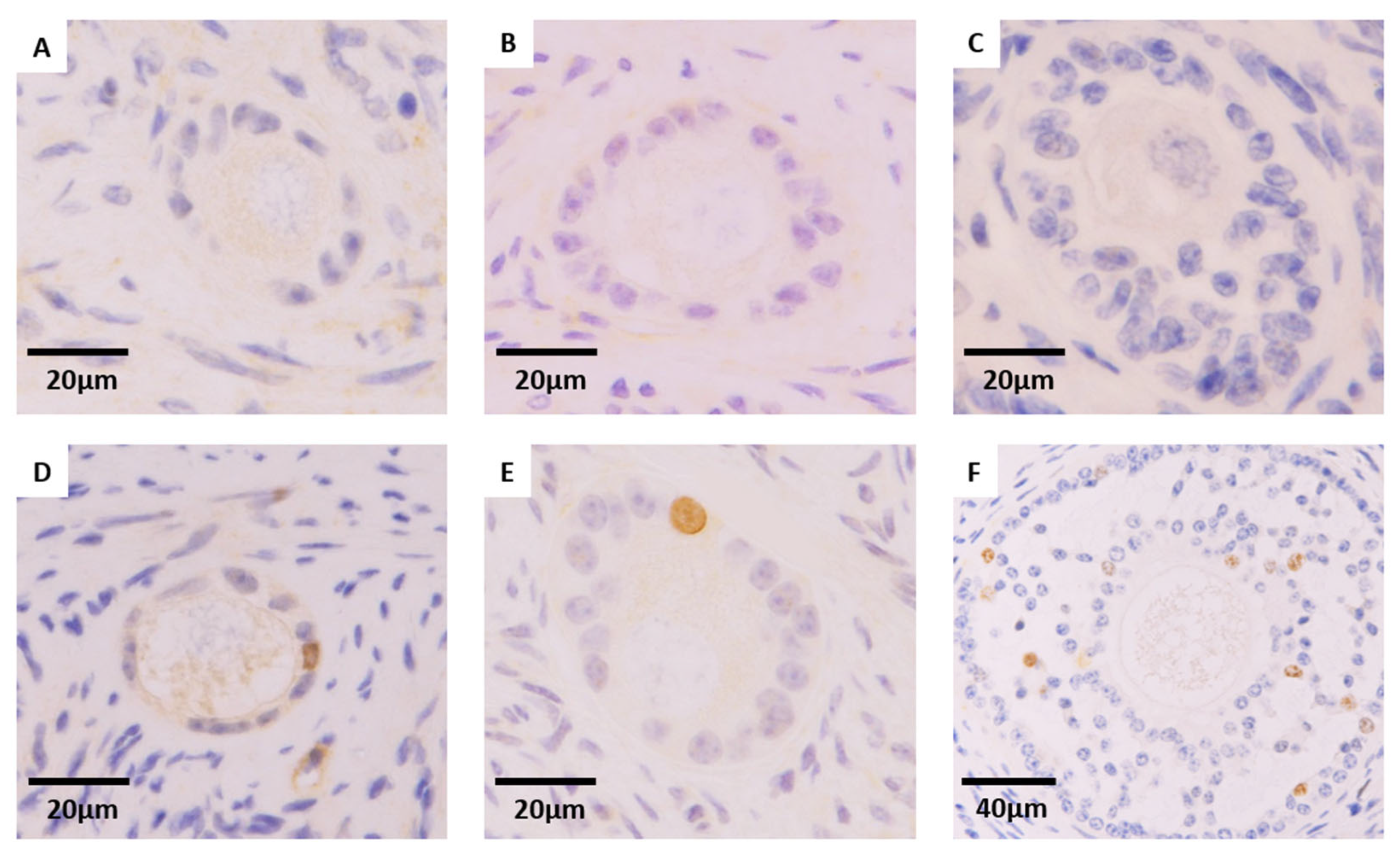

3.3. Effect of Cryopreservation Procedure on Granulosa Cell Proliferation of Preantral Follicles (Ki67 Expression)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Erickson, B.H. Development and senescence of the postnatal bovine ovary. J. Anim. Sci. 1966, 25, 800–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girard, A.; Dufort, I.; Douville, G.; Sirard, M.A. Global gene expression in granulosa cells of growing, plateau and atretic dominant follicles in cattle. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2015, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Silva-Santos, K.C.; Santos, G.M.; Siloto, L.S.; Hertel, M.F.; Andrade, E.R.; Rubin, M.I.; Sturion, L.; Melo-Sterza, F.A.; Seneda, M.M. Estimate of the population of preantral follicles in the ovaries of Bos taurus indicus and Bos taurus taurus cattle. Theriogenology 2011, 76, 1051–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tharasanit, T.; Thuwanut, P. Oocyte Cryopreservation in Domestic Animals and Humans: Principles, Techniques and Updated Outcomes. Animals 2021, 11, 2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ogawa, B.; Ueno, S.; Nakayama, N.; Matsunari, H.; Nakano, K.; Fujiwara, T.; Ikezawa, Y.; Nagashima, H. Developmental ability of porcine in vitro matured oocytes at the meiosis II stage after vitrification. J. Reprod. Dev. 2010, 56, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, R.A.; Wallace, W.H.; Baird, D.T. Ovarian cryopreservation for fertility preservation: Indications and outcomes. Reproduction 2008, 136, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herraiz, S.; Novella-Maestre, E.; Rodríguez, B.; Díaz, C.; Sánchez-Serrano, M.; Mirabet, V.; Pellicer, A. Improving ovarian tissue cryopreservation for oncologic patients: Slow freezing versus vitrification, effect of different procedures and devices. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 101, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikiforov, D.; Russo, V.; Nardinocchi, D.; Bernabò, N.; Mattioli, M.; Barboni, B. Innovative multi-protectoral approach increases survival rate after vitrification of ovarian tissue and isolated follicles with improved results in comparison with conventional method. J. Ovarian Res. 2018, 11, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Locatelli, Y.; Calais, L.; Duffard, N.; Lardic, L.; Monniaux, D.; Piver, P.; Mermillod, P.; Bertoldo, M.J. In vitro survival of follicles in prepubertal ewe ovarian cortex cryopreserved by slow freezing or non-equilibrium vitrification. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2019, 36, 1823–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Candelaria, J.I.; Denicol, A.C. Assessment of ovarian tissue and follicular integrity after cryopreservation via slow freezing or vitrification followed by in vitro culture. FS Sci. 2024, 5, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díez, C.; Muñoz, M.; Caamaño, J.N.; Gómez, E. Cryopreservation of the bovine oocyte: Current status and perspectives. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2012, 47, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prentice-Biensch, J.R.; Singh, J.; Mapletoft, R.J.; Anzar, M. Vitrification of immature bovine cumulus-oocyte complexes: Effects of cryoprotectants, the vitrification procedure and warming time on cleavage and embryo development. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2012, 10, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hwang, I.S.; Hochi, S. Recent progress in cryopreservation of bovine oocytes. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 570647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ríos, G.L.; Suqueli García, M.F.; Manrique, R.J.; Buschiazzo, J. Optimization of bovine oocyte cryopreservation: Membrane fusion competence and cell death of linoleic acid-in vitro matured oocytes subjected to vitrification. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1628947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alkali, I.M.; Colombo, M.; De Iorio, T.; Piotrowska, A.; Rodak, O.; Kulus, M.J.; Niżański, W.; Dziegiel, P.; Luvoni, G.C. Vitrification of feline ovarian tissue: Comparison of protocols based on equilibration time and temperature. Theriogenology 2024, 224, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, R.R.; Amorim, C.; Cecconi, S.; Fassbender, M.; Imhof, M.; Lornage, J.; Paris, M.; Schoenfeldt, V.; Martinez-Madrid, B. Cryopreservation of ovarian tissue: An emerging technology for female germline preservation of endangered species and breeds. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2010, 122, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, T.; Pavone, M. Exploring the Frontiers of Ovarian Tissue Cryopreservation: A Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kagawa, N.; Silber, S.; Kuwayama, M. Successful vitrification of bovine and human ovarian tissue. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2009, 18, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, J.F.; Jeff Huang, C.C. Bovine models for human ovarian diseases. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2022, 189, 101–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbato, V.; Genovese, V.; De Gregorio, V.; Di Nardo, M.; Travaglione, A.; De Napoli, L.; Fragomeni, G.; Zanetti, E.M.; Adiga, S.K.; Mondrone, G.; et al. Dynamic in vitro culture of bovine and human ovarian tissue enhances follicle progression and health. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gómez-Álvarez, M.; Agustina-Hernández, M.; Francés-Herrero, E.; Bueno-Fernandez, C.; Alonso-Frías, P.; Corpas, N.; Faus, A.; Pellicer, A.; Cervelló, I. Generation of healthy bovine ovarian organoids: A proof-of-concept derivation technique. J. Ovarian Res. 2025, 18, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khattak, H.; Malhas, R.; Craciunas, L.; Afifi, Y.; Amorim, C.A.; Fishel, S.; Silber, S.; Gook, D.; Demeestere, I.; Bystrova, O.; et al. Fresh and cryopreserved ovarian tissue transplantation for preserving reproductive and endocrine function: A systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2022, 28, 400–416, Erratum in Hum. Reprod. Update 2022, 28, 455. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmac015. PMID: 35199164; PMCID: PMC9733829.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, A.A.; Kubo, H.; Handa, N.; Hanna, M.; Laronda, M.M. A Systematic Review of Ovarian Tissue Transplantation Outcomes by Ovarian Tissue Processing Size for Cryopreservation. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 918899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Erden, M.; Uyanik, E.; Demeestere, I.; Oktay, K.H. Perinatal outcomes of pregnancies following autologous cryopreserved ovarian tissue transplantation: A systematic review with pooled analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 231, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schallmoser, A.; Einenkel, R.; Färber, C.; Emrich, N.; John, J.; Sänger, N. The effect of high-throughput vitrification of human ovarian cortex tissue on follicular viability: A promising alternative to conventional slow freezing? Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 307, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cheng, H.; Ye, X.; Zhu, H.; Li, Y.; Liang, X.; Chang, X.; Cui, H. An experimental study on autologous transplantation of fresh ovarian tissue in sheep. Gynecol. Obstet. Clin. Med. 2021, 1, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, S.; Joshi, V.B.; Larson, N.B.; Young, M.C.; Bilal, M.; Walker, D.L.; Khan, Z.; Granberg, C.F.; Chattha, A.; Zhao, Y. Vitrification versus slow freezing of human ovarian tissue: A systematic review and meta-analysis of histological outcomes. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2023, 40, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bizarro-Silva, C.; Bergamo, L.Z.; Costa, C.B.; González, S.M.; Yokomizo, D.N.; Rossaneis, A.C.; Verri Junior, W.A.; Sudano, M.J.; Andrade, E.R.; Alfieri, A.A.; et al. Evaluation of Cryopreservation of Bovine Ovarian Tissue by Analysis of Reactive Species of Oxygen, Toxicity, Morphometry, and Morphology. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sugishita, Y.; Taylan, E.; Kawahara, T.; Shahmurzada, B.; Suzuki, N.; Oktay, K. Comparison of open and a novel closed vitrification system with slow freezing for human ovarian tissue cryopreservation. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2021, 38, 2723–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Deligiannis, S.P.; Kask, K.; Modhukur, V.; Boskovic, N.; Ivask, M.; Jaakma, Ü.; Damdimopoulou, P.; Tuuri, T.; Velthut-Meikas, A.; Salumets, A. Investigating the impact of vitrification on bovine ovarian tissue morphology, follicle survival, and transcriptomic signature. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2024, 41, 1035–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Galbinski, S.; Kowalewski, L.S.; Grigolo, G.B.; da Silva, L.R.; Jiménez, M.F.; Krause, M.; Frantz, N.; Bös-Mikich, A. Comparison between two cryopreservation techniques of human ovarian cortex: Morphological aspects and the heat shock response (HSR). Cell Stress Chaperones 2021, 27, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lu, X.L.; Yu, J.; Zhang, G.; Wei, Z.T.; Li, J.T.; Zhang, J.M. Effects of varying tissue sizes on the efficiency of baboon ovarian tissue vitrification. Cryobiology 2014, 69, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorricho, C.M.; Tavares, M.R.; Apparício, M.; Fonseca-Alves, C.E.; Macente, B.I.; Mansano, C.F.M.; Toniollo, G.H. Vitrification of cat ovarian tissue: Does fragment size matters? Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2018, 53, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, M.; Bos-Mikich, A.; Frantz, N.; Rodrigues, J.L.; Brunetto, A.L.; Schwartsmann, G. The effects of sample size on the outcome of ovarian tissue cryopreservation. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2010, 45, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupont, Á.; Sanguinet, E.; Ferreira, M.; Ramos, L.; Lothhammer, N.; Frantz, N.; Bos-Mikich, A. Morphological study on the effects of sample size on ovarian tissue vitrification. JBRA Assist. Reprod. 2022, 26, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Faheem, M.S.; Carvalhais, I.; Chaveiro, A.; Moreira da Silva, F. In vitro oocyte fertilization and subsequent embryonic development after cryopreservation of bovine ovarian tissue, using an effective approach for oocyte collection. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2011, 125, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, M.; Peirson, S.N.; Hankins, M.W.; Foster, R.G. Long-term constant light induces constitutive elevated expression of mPER2 protein in the murine SCN: A molecular basis for Aschoff’s rule? J. Biol. Rhythms 2005, 20, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amorim, C.A.; Jacobs, S.; Devireddy, R.V.; Van Langendonckt, A.; Vanacker, J.; Jaeger, J.; Luyckx, V.; Donnez, J.; Dolmans, M.M. Successful vitrification and autografting of baboon (Papio anubis) ovarian tissue. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 2146–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, K.L.; Byskov, A.G.; Nyboe Andersen, A.; Müller, J.; Yding Andersen, C. Density and distribution of primordial follicles in single pieces of cortex from 21 patients and in individual pieces of cortex from three entire human ovaries. Hum. Reprod. 2003, 18, 1158–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, K.A.; Alves, B.G.; Gastal, G.D.A.; Haag, K.T.; Gastal, M.O.; Figueiredo, J.R.; Gambarini, M.L.; Gastal, E.L. Preantral follicle density in ovarian biopsy fragments and effects of mare age. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2017, 29, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcozzi, S.; Vicenti, R.; La Sala, G.; Lamsira, H.K.; Scarica, C.; Bertani, N.; De Felici, M.; Fabbri, R.; Klinger, F.G. Short-Term In Vitro Culture of Human Ovarian Tissue: A Comparative Study of Serum Supplementation for Primordial Follicle Survival. Life 2025, 15, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Follicles with Normal Morphology (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Ctrl | SFT | VW1 | VW2 |

| Small | 85.09 ± 10.98 | 86.66 ± 10.15 a | 39.28 ± 17.93 | 76.19 ± 13.29 |

| Large | 85.50 ± 10.67 | 79.35 ± 13.84 b | 38.27 ± 15.80 | 72.72 ± 11.59 |

| Small | Preantral Follicle Developmental Stage (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group (N of MNFs) | Primordial | Primary | Secondary |

| Ctrl (635) | 65.37 (55.41–72.65) | 26.09 (20.00–37.04) | 13.39 (10.00–19.17) |

| SFT (618) | 63.07 (51.04–70.57) | 26.67 (22.25–33.33) | 13.33 (10.00–18.54) |

| VW1 (362) | 66.67 (55.56–72.73) | 27.78 (21.11–35.68) | 16.67 (12.50–21.11) |

| VW2 (475) | 69.34 (59.12–80.00) | 21.11 (17.80–27.60) | 12.13 (8.33–19.55) |

| Large | Preantral Follicle Developmental Stage (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group (N of MNFs) | Primordial | Primary | Secondary |

| Ctrl (1018) | 59.09 (50.00–66.67) | 30.36 (25.00–34.62) | 13.12 (7.57–20.71) a |

| SFT (793) | 62.20 (50.32–69.81) | 25.00 (19.20–31.44) | 15.79 (7.02–17.27) a |

| VW1 (248) | 62.50 (50.00–75.00) | 31.67 (20.56–38.33) | 25.00 (15.48–33.33) b |

| VW2 (716) | 62.50 (54.80–71.43) | 28.08 (22.22–33.65) | 12.50 (8.33–16.53) a |

| Ki67-Positive Follicles (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Primary | Secondary | ||

| Small | Large | Small | Large | |

| Ctrl | 5.07% (11/217) | 5.20% (17/327) | 46.67% (42/90) | 38.60% (44/114) |

| SFT | 6.03% (14/232) | 5.07% (11/217) | 48.51% (49/101) | 50.94% (54/106) |

| VW1 | 3.06% (3/98) | 3.03% (2/66) | 54.55% (36/66) | 50% (15/30) |

| VW2 | 10.79% (15/139) a | 5.17% (12/232) b | 60.32% (38/63) | 52.69% (49/93) |

| Small | Ki67-Positive Follicles (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Primordial | Primary | Secondary | |

| Ctrl | 0% (0/515) a | 5.07% (11/217) b | 46.67% (42/90) c | p < 0.001 |

| SFT | 0% (0/556) a | 6.03% (14/232) b | 48.51% (49/101) c | p < 0.001 |

| VW1 | 0% (0/250) a | 3.06% (3/98) b | 54.55% (36/66) c | p < 0.001 |

| VW2 | 0% (0/419) a | 10.79% (15/139) b | 60.32% (38/63) c | p < 0.001 |

| Large | Ki67-Positive Follicles (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Primordial | Primary | Secondary | |

| Ctrl | 0.26% (2/774) a | 5.20% (17/327) b | 38.60% (44/114) c | p < 0.001 |

| SFT | 0% (0/655) a | 5.07% (11/217) b | 50.94% (54/106) c | p < 0.001 |

| VW1 | 0% (0/158) a | 3.03% (2/66) a | 50% (15/30) b | p < 0.001 |

| VW2 | 0% (0/553) a | 5.17% (12/232) b | 52.69% (49/93) c | p < 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Romero, P.; Carrocera, S.; García, A.; Nieto, P.; Iglesias, T.; Muñoz, M.; Díez, C. Approaching Standardization of Bovine Ovarian Cortex Cryopreservation: Impact of Cryopreservation Protocols and Tissue Size on Preantral Follicle Population. Animals 2026, 16, 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020266

Romero P, Carrocera S, García A, Nieto P, Iglesias T, Muñoz M, Díez C. Approaching Standardization of Bovine Ovarian Cortex Cryopreservation: Impact of Cryopreservation Protocols and Tissue Size on Preantral Follicle Population. Animals. 2026; 16(2):266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020266

Chicago/Turabian StyleRomero, Paula, Susana Carrocera, Aurora García, Pilar Nieto, Tania Iglesias, Marta Muñoz, and Carmen Díez. 2026. "Approaching Standardization of Bovine Ovarian Cortex Cryopreservation: Impact of Cryopreservation Protocols and Tissue Size on Preantral Follicle Population" Animals 16, no. 2: 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020266

APA StyleRomero, P., Carrocera, S., García, A., Nieto, P., Iglesias, T., Muñoz, M., & Díez, C. (2026). Approaching Standardization of Bovine Ovarian Cortex Cryopreservation: Impact of Cryopreservation Protocols and Tissue Size on Preantral Follicle Population. Animals, 16(2), 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020266