Absence of Host-Specific Hemotropic Mycoplasmas in Horses and Donkeys from Croatia: First Systematic Survey in Southeastern Europe

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

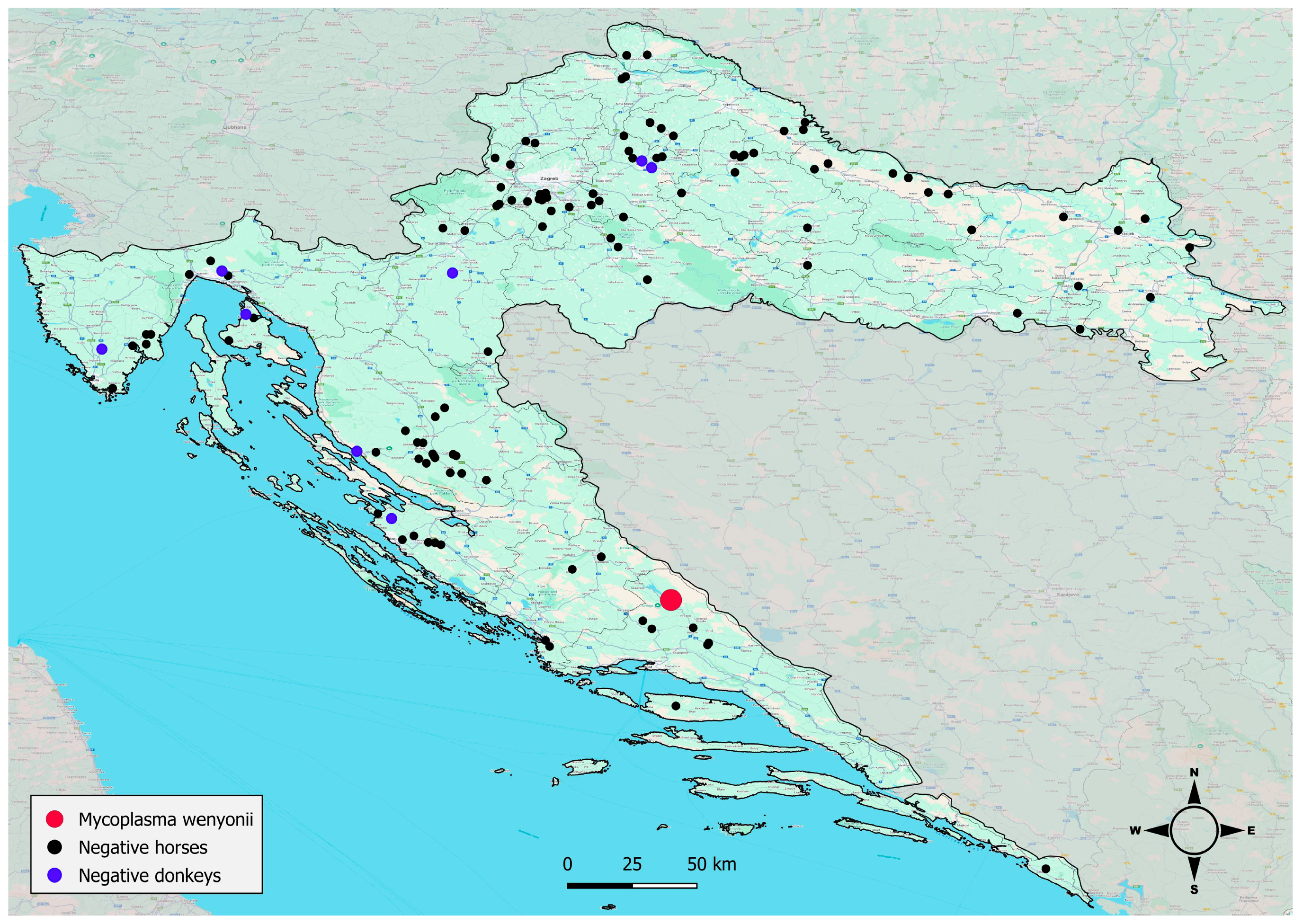

2.1. Study Area, Animals and Study Design

2.2. Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

2.3. Molecular Detection and Sequencing

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Messick, J.B. Hemotrophic mycoplasmas (hemoplasmas): A review and new insights into pathogenic potential. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2004, 33, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, M.; Stadler, J.; Ritzmann, M.; Ade, J.; Hoelzle, K.; Hoelzle, L.E. Hemotrophic mycoplasmas-vector transmission in livestock. Microorganisms 2004, 12, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žilić, D.J.; Naletilić, Š.; Mihaljević, Ž.; Gagović, E.; Špičić, S.; Reil, I.; Duvnjak, S.; Tuk, M.Z.; Hodžić, A.; Beck, R. Hemotropic pathogens in aborted fetuses of domestic ruminants: Transplacental transmission and implications for reproductive loss. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1632135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoelzle, K.; Ade, J.; Hoelzle, L.E. Persistence in livestock mycoplasmas—A key role in infection and pathogenesis. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 2020, 7, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretillat, S. L’he’mobartonellose equine au Niger. Bull. Acad. Vet. Fr. 1978, 51, 351–358. [Google Scholar]

- Dieckmann, S.M.; Winkler, M.; Groebel, K.; Dieckmann, M.P.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Hoelzle, K.; Wittenbrink, M.M.; Hoelzle, L.E. Haemotrophic Mycoplasma infection in horses. Vet. Microbiol. 2010, 145, 351–353. [Google Scholar]

- Dieckmann, S.M.; Hoelzle, K.; Dieckmann, M.P.; Straube, I.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Hoelzle, L.E. Occurrence of hemotrophic mycoplasmas in horses with correlation to hematological findings. Vet. Microbiol. 2012, 160, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happi, A.N.; Oluniyi, P.E. A rare case of equine Haemotropic Mycoplasma infection in Nigeria. Niger. Vet. J. 2020, 41, 274–286. [Google Scholar]

- Kalantari, M.; Sharifiyazdi, H.; Ghane, M.; Nazifi, S. The occurrence of hemotropic Mycoplasma ovis-like species in horses. Prev. Vet. Med. 2020, 175, 104877. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kakimori, M.T.A.; Barros, L.D.; Collere, F.C.M.; Ferrari, L.D.R.; de Matos, A.; Lucas, J.I.; Coradi, V.S.; Mongruel, A.C.B.; Aguiar, D.M.; Machado, R.Z.; et al. First molecular detection of Mycoplasma ovis in horses from Brazil. Acta. Trop. 2023, 237, 106697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballados-González, G.G.; Cruz-Romero, A.; Martínez-Hernández, J.M.; Aguilar-Dominguez, M.; Vieira, R.F.C.; Grostieta, E.; Becker, I.; Sánchez-Montes, S. Confirmation of the presence of Hemotropic Mycoplasma species in working equids from Veracruz, Mexico. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2025, 57, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, R.F.; Vidotto, O.; Vieira, T.S.; Guimaraes, A.M.; Santos, A.P.; Nascimento, N.C.; Santos, N.J.; Martins, T.F.; Labruna, M.B.; Marcondes, M.; et al. Molecular investigation of hemotropic mycoplasmas in human beings, dogs and horses in a rural settlement in southern Brazil. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2015, 57, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, J.D.M.; Mongruel, A.C.B.; Machado, C.A.L.; Chiyo, L.; Leandro, A.S.; Britto, A.S.; Martins, T.F.; Barros-Filho, I.R.; Biondo, A.W.; Perotta, J.H.; et al. Tick-borne pathogens in carthorses from Foz do Iguaçu City, Paraná State, southern Brazil: A tri-border area of Brazil, Paraguay and Argentina. Vet. Parasitol. 2019, 273, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altay, K.; Erol, U.; Sahin, O.F.; Ulucesme, M.C.; Aytmirzakizi, A.; Aktas, M. Survey of tick-borne pathogens in grazing horses in Kyrgyzstan: Phylogenetic analysis, genetic diversity, and prevalence of Theileria equi. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1359974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varanat, M.; Maggi, R.G.; Linder, K.E.; Breitschwerdt, E.B. Molecular prevalence of Bartonella, Babesia, and hemotropic Mycoplasma sp. in dogs with splenic disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2011, 25, 1284–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongruel, A.C.B.; Spanhol, V.C.; Valente, J.D.M.; Porto, P.P.; Ogawa, L.; Otomura, F.H.; Marquez, E.d.S.; André, M.R.; Vieira, T.S.W.J.; Vieira, R.F.d.C. Survey of vector-borne and nematode parasites involved in the etiology of anemic syndrome in sheep from Southern Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2020, 29, e007320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagawa, M.; Matsumoto, K.; Yokoyama, N.; Inokuma, H. Prevalence and Molecular Analyses of Hemotrophic Mycoplasma spp. (Hemoplasmas) Detected in Sika Deer (Cervus nipponyesoensis) in Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2013, 76, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byamukama, B.; Tumwebaze, M.A.; Tayebwa, D.S.; Byaruhanga, J.; Angwe, M.K.; Li, J.; Galon, E.M.; Liu, M.; Li, Y.; Ji, S.; et al. First Molecular Detection and Characterization of Hemotropic Mycoplasma Species in Cattle and Goats from Uganda. Animals 2020, 10, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, E.P.; Vidotto, O.; Almeida, J.C.; Ribeiro, L.P.; Borges, M.V.; Pequeno, W.H.; Stipp, D.T.; de Oliveira, C.J.; Biondo, A.W.; Vieira, T.S.; et al. Serological and molecular detection of Theileria equi in sport horses of northeastern Brazil. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016, 47, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, M.R.; Duarte, J.M.B.; Gonçalves, L.R.; Sacchi, A.B.V.; Jusi, M.M.G.; Machado, R.Z. New records and genetic diversity of Mycoplasma ovis in free-ranging deer in Brazil. Epidemiol. Infect. 2020, 148, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, C.A.L.; Vidotto, O.; Conrado, F.O.; Santos, N.J.R.; Valente, J.D.M.; Barbosa, I.C.; Trindade, P.W.S.; Garcia, J.L.; Biondo, A.W.; Vieira, T.S.W.J.; et al. Mycoplasma ovis infection in goat farms from northeastern Brazil. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 55, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, R.G.; Compton, S.M.; Trull, C.L.; Mascarelli, P.E.; Mozayeni, B.R.; Breitschwerdt, E.B. Infection with hemotropic Mycoplasma species in patients with or without extensive arthropod or animal contact. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 3237–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, A.C.; Kumaragurubaran, K.; Gunasekaran, K.; Murugasamy, S.A.; Arunachalam, S.; Annamalai, R.; Ragothaman, V.; Ramaswamy, S. Molecular Detection of Hemoplasma in animals in Tamil Nadu, India and Hemoplasma genome analysis. Vet. Res. Commun. 2024, 48, 955–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Fernández, A.; Maggi, R.; Martín-Valls, G.E.; Baxarias, M.; Breitschwerdt, E.B.; Solano-Gallego, L. Prospective serological and molecular cross-sectional study focusing on Bartonella and other blood-borne organisms in cats from Catalonia (Spain). Parasit. Vectors 2022, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, L.B.; Calchi, A.C.; Vultão, J.G.; Yogui, D.R.; Kluyber, D.; Alves, M.H.; Desbiez, A.L.J.; de Santi, M.; Soares, A.G.; Soares, J.F.; et al. Molecular investigation of haemotropic Mycoplasmas and Coxiella burnetii in free-living Xenarthra mammals from Brazil, with evidence of new haemoplasma species. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, e1877–e1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Konstantinović, N.; Gotić, J.; Baban, M.; Csik, G.; Listeš, E.; Gagović, E.; Jurković Žilić, D.; Arežina, I.; Šubara, G.; Čulina, F.E.; et al. Absence of Host-Specific Hemotropic Mycoplasmas in Horses and Donkeys from Croatia: First Systematic Survey in Southeastern Europe. Animals 2026, 16, 263. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020263

Konstantinović N, Gotić J, Baban M, Csik G, Listeš E, Gagović E, Jurković Žilić D, Arežina I, Šubara G, Čulina FE, et al. Absence of Host-Specific Hemotropic Mycoplasmas in Horses and Donkeys from Croatia: First Systematic Survey in Southeastern Europe. Animals. 2026; 16(2):263. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020263

Chicago/Turabian StyleKonstantinović, Nika, Jelena Gotić, Mirjana Baban, Goran Csik, Ema Listeš, Ema Gagović, Daria Jurković Žilić, Ivan Arežina, Gordan Šubara, Franka Emilija Čulina, and et al. 2026. "Absence of Host-Specific Hemotropic Mycoplasmas in Horses and Donkeys from Croatia: First Systematic Survey in Southeastern Europe" Animals 16, no. 2: 263. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020263

APA StyleKonstantinović, N., Gotić, J., Baban, M., Csik, G., Listeš, E., Gagović, E., Jurković Žilić, D., Arežina, I., Šubara, G., Čulina, F. E., Delić, N., Višal, D., Zvonar, Z., Beck, R., & Kostelić, A. (2026). Absence of Host-Specific Hemotropic Mycoplasmas in Horses and Donkeys from Croatia: First Systematic Survey in Southeastern Europe. Animals, 16(2), 263. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020263