1. Introduction

Since industrialization, global warming has been occurring worldwide, including in Korea, with unprecedented climate change manifesting particularly since the latter half of the 20th century [

1]. Examining changes in seasonal duration, summer periods with average temperatures of 25 °C or higher lasted 98 days during an earlier 30-year period (1912–1941), whereas in a recent 30-year period (1988–2017), this figure increased to 117 days, representing a 19-day extension in exposure to high summer temperatures [

2]. These climate changes directly impact the agricultural sector and represent a major factor causing decreased livestock productivity and economic losses in the livestock industry.

In response to heat stress, animals activate both physiological and behavioral heat dissipation mechanisms. Dermal arteriole dilation redirects blood flow to the skin surface to promote heat exchange with the environment, while increased sweating and mouth breathing enhance evaporative cooling [

3,

4]. Concurrently, behavioral adjustments including shade-seeking and reduced activity help minimize metabolic heat generation and support thermoregulation [

5]. Heat stress induces various physiological changes in dairy cows, affecting their behavior, metabolism, and productivity [

6]. When the temperature–humidity index (THI) exceeds 72, dairy cows begin to experience moderate heat stress [

7], and break points which seriously decrease productivity are reported around THI values of 80–82 for milk yield of Holstein cows in South Korea [

8]. Climate changes directly lead to decreased milk yield and cause multiple productivity losses, including alterations in milk composition, reduced reproductive efficiency, and increased disease incidence, which ultimately have direct negative impacts on farm profitability.

The rumen serves as a fermentation vat where microbial metabolism generates considerable metabolic heat. During heat stress, ruminants reduce feed intake to minimize the thermogenic effect of digestion and lower overall body heat production [

9]. This decrease in feed intake is one of the primary factors contributing to the decline in milk production in dairy cows. Rumen temperature typically exceeds rectal temperature under normal feeding conditions due to heat generated by microbial fermentation [

10]. Therefore, feeding nutrients with rumen-undegradable characteristics can sustain nutrient intake while minimizing increases in core body temperature.

Nutritionally, GABA is catabolized by mitochondrial GABA transaminase (GABA-T) to form succinic semialdehyde, which is subsequently oxidized to succinate and incorporated into the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, thereby contributing to cellular energy production [

11]. In high-temperature environments (THI 78–80 or higher), cows supplemented with GABA exhibit greater feed intake as well as increased milk protein and lactose content compared to controls [

12,

13]. Supplementing 0.8–1.2 g/day of GABA has been shown to increase milk production and milk protein yield, reduce non-esterified fatty acids (NEFAs; indicating improved energy metabolism), and raise antioxidant markers such as glutathione peroxidase and superoxide dismutase [

14]. Consequently, the provision of ruminally protected GABA may mitigate heat stress-induced decrements in productive performance, despite the paucity of research addressing this hypothesis. Therefore, this study was conducted to evaluate the effect of rumen-protected GABA supplementation on milk productivity of lactating Holstein cows.

4. Discussion

Heat stress of livestock animals is mainly evaluated using THI, which is calculated using temperature and relative humidity [

18]. The THI is classified by the productivity of the livestock animal, and it has four fractions. Generally, a THI threshold of 72 is used, as Holstein cow productivity begins to decline at or above this value [

19]. The THI classification was divided into normal (THI under 68), mild (THI 68 to 72), moderate (THI 72 to 80), severe (THI 80 to 90), and danger zone (THI over 90). A previous study used a slightly different scale (e.g., normal < 70, alert 70–78, danger 79–82, emergency > 82), but similarly identified THI values above 72 as indicative of heat stress onset [

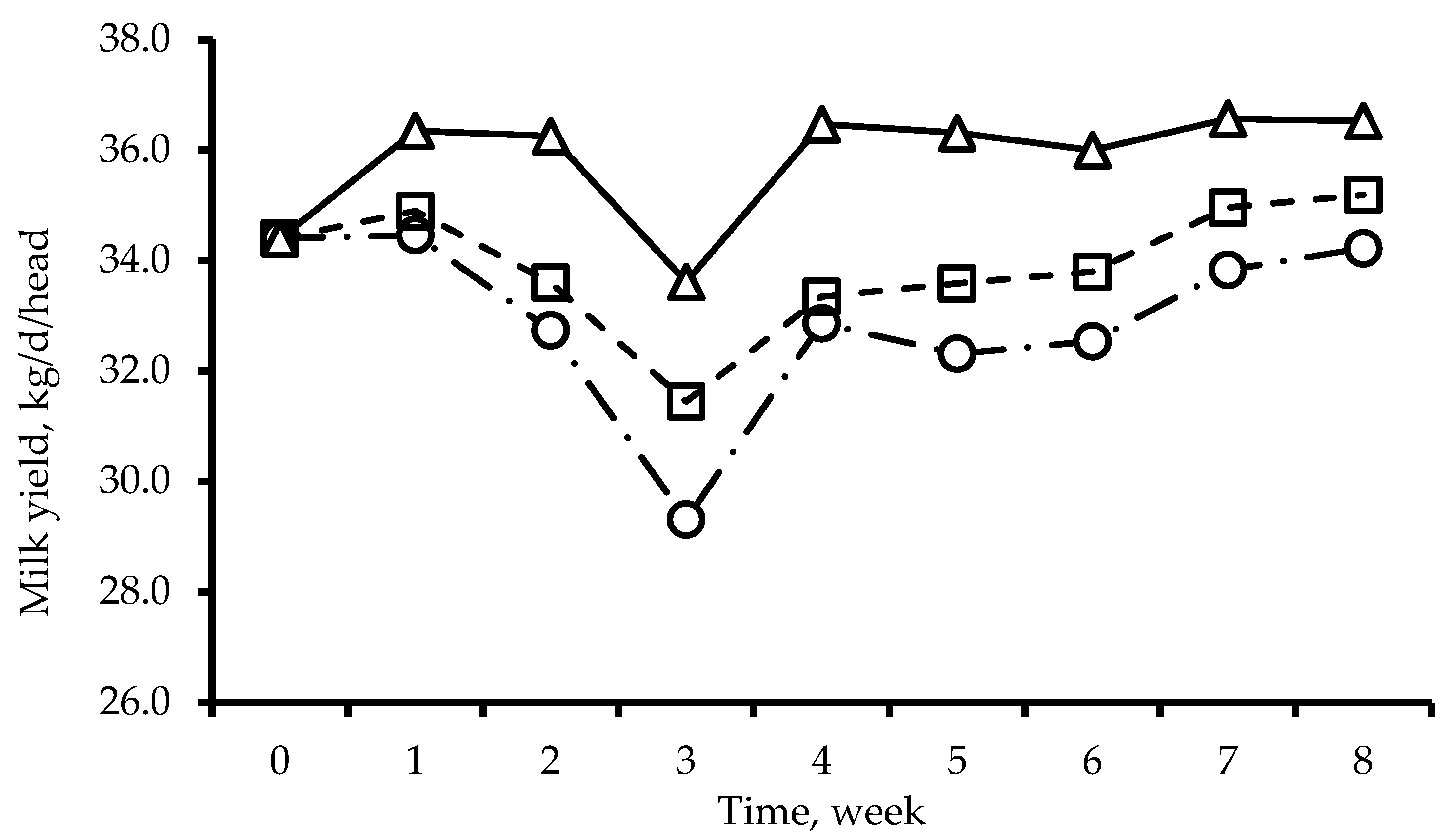

20]. In this study, during week 0 to week 6, minimum THI was shown to be greater than standard thresholds (THI 72) of other studies and meant that most experimental cows were affected by heat stress during experimental periods. As maximum THI was shown to be under 90 during the entire experimental period, it is considered that it did not affect mortality risks. The decline in milk yield began after week 1, when the daily proportion of time under severe heat stress conditions (THI 80 to 89) exceeded the proportion of time below the moderate heat stress between weeks 1 and 2 (

Table 3 and

Figure 1). Recovery of milk yield was observed from week 4 onward (

Figure 1), corresponding to a decrease in daily exposure to severe heat stress conditions (THI 80–89) between weeks 3 and 4 (

Table 3). Following the return of THI values below the heat stress threshold after week 6, rapid recovery of milk yield was observed in all treatments, with substantial improvement evident within 7 days (between weeks 6 and 7). Previous research has demonstrated that milk yield can decrease by 35% during 10 days of severe heat stress exposure (THI 84), with 60% recovery of the lost production achieved within 14 days post-stress [

21]. In this study, milk yield of the control group declined by a maximum of 14.7% during the period of increasing severe heat stress exposure, reaching the lowest point in week 3. Following the reduction in severe heat stress, milk yield recovered by approximately 8.8% and remained at this level through week 6. However, in a previous study, it was reported that the THI ratio threshold for a decline in productivity was −100 according to the criteria calculated by the method of Nam et al. [

15], while in the present study, a decrease was observed starting at −144.4. This may indicate that the constant interval values used for THI ratio calculation [

15] do not universally ensure accuracy across all studies. To improve model performance, it would be advisable to collect temperature, humidity, and flow rate data under a variety of environmental conditions and refine the model accordingly.

In this study, all animals received the same amount of feed under restricted feeding conditions and were exposed to identical heat stress environments. Therefore, GABA supplementation was the only difference between treatment groups. Nutritionally, GABA is metabolized by mitochondrial GABA transaminase (GABA-T), producing succinic semialdehyde, which is then converted to succinate and enters the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, thereby linking GABA metabolism to cellular energy production [

11]. Specifically, GABA, which escapes rumen degradation, can directly participate in carbohydrate metabolism without conversion to volatile fatty acids. This may explain the increased milk yield observed when rumen-protected GABA was supplemented. Feed intake is a major source of heat generation in ruminants, and reducing feed intake serves to lower metabolic heat load during heat stress conditions [

16]. Although ruminal temperature was not measured in this study and GABA did not affect rectal temperature, previous research demonstrated a strong correlation between daily THI and rumen temperature during heat stress [

15], suggesting that heat stress in animals is closely associated with external environmental conditions. Rumen-protected GABA, which bypasses degradation in the rumen, can be directly utilized as a nutrient by the animal. This approach is believed to help reduce body heat gain and provide an effective source of energy, particularly under heat stress conditions.

In particular, in this study, the milk yield in the GABA treatment group was consistently higher than that of the control group during the entire experimental period (

Figure 1), and the trends observed in both milk yield and 3.5% fat-corrected milk (FCM) indicate the positive effect of GABA supplementation (

Table 5). Direct correlations between GABA and milk fat are less frequently reported, but some studies suggest overall positive effects on milk performance, especially under heat stress [

12,

14]. Conversely, several studies have demonstrated that supplementing dairy cows with GABA, particularly in rumen-protected form, prevents a decrease in milk production and milk protein content, especially during periods of heat stress [

12,

13]. On the other hand, a previous study reported a quadratic response to GABA supplementation levels, with milk protein increases being greater at lower doses [

12]. These results suggest that milk protein response to GABA is not dose-dependent beyond certain levels. Although there is no established direct biochemical correlation between the activity of GABA and lactose concentrations, GABA participates in insulin and glucose regulation, both of which are essential for lactose synthesis [

22]. Although the precise mechanism underlying the GABA supplementation effect in milk fat remains unclear, multiple studies have established that GABA participates in carbohydrate metabolism and contributes to improved energy metabolism in dairy cows. The behavioral changes observed during the experimental period following rumen-protected GABA supplementation clearly demonstrate rumen-protected GABA’s effectiveness. In the rumen-protected GABA treatment group, both activity time and feed intake time increased significantly, while rest and rumination times decreased significantly. Previous studies have consistently confirmed that GABA supplementation leads to increased feed intake time, changes in rumination and rest patterns, and reduced oxidative stress in the body [

12,

13]. However, the restricted feeding protocol in this study prevented assessment of GABA’s effect on voluntary feed intake, which increased in previous studies.

Overall, supplementation with rumen-protected GABA appears to beneficially reduce heat generated from ruminal fermentation by providing additional nutrients during periods of heat stress. This nutritional strategy increases feed intake and helps prevent productivity losses in ruminants exposed to high ambient temperatures, primarily through positive physiological and metabolic effects.