1. Introduction

Internal parasites pose a significant concern for both people and animals [

1]. In small ruminants, gastrointestinal parasitism may result in substantial direct and indirect economic losses; for example, a 16% reduction in farmers’ profit, primarily due to a 50% reduction in weight gain, has been referred to parasitic infections in goats [

2]. Parasitism is also associated with anorexia, decreased resilience to illness, and in severe cases, mortality [

3]. The effects of parasitism on the economy and small ruminants’ health are exacerbated by the emerging challenge of increase in anthelmintic resistance [

4]. Therefore, both the World Health Organization and the World Association for the Advancement of Veterinary Parasitology have recommended fecal egg counts (

FECs) as a monitoring tool in humans [

1] and for assessing intestinal parasite infections in livestock [

5].

An essential component of targeted selective treatment programs in small ruminants is FEC [

6] and it can also be used to monitor drug efficacy and guide treatment strategies based on parasite species prevalence and resistance status [

7]. Despite its widespread use, FEC methods are time consuming, require laboratory equipment and trained personnel, meanwhile the underlying methodology has not altered much in the last century [

8,

9].

The McMaster method, first introduced in the 1930s [

9], is a traditional quantitative egg-counting chamber technique that is still widely accepted as the industry standard today. Over time, multiple adaptations of the McMaster technique have been developed, including chamber-based methods such as the Moredun method [

10], FECPAK [

11], FLOTAC [

12], and Mini-FLOTAC [

13], all of which can be considered enhancements of the original McMaster principle. Recently, an alternative approach of quantifying fecal eggs has been introduced by implementing new technologies that combine dual-step sample processing with fluorescence-based imaging and artificial intelligence-driven classification and counting (Parasight

®; MEP Equine Solutions, Lexington, KY, USA). This approach is consistent with earlier methods that used fluorescent chitin-binding probes to label helminth eggs, combined with automated image analysis for detection and enumeration [

14,

15]. Although the proprietary details of the commercial platform remain undisclosed, the system appears to rely on the same fluorescence-imaging-plus-AI framework. This is an important shift from both manual microscopy and traditional McMaster flotation approach to implementation of sophisticated and objective image-recognition systems that employ fluorescence associated techniques.

Adoption of novel diagnostic technologies is intrinsically challenging, as all procedures regardless of design might be subjected to variability arising from both random and systematic sources of error. Understanding this variability and rigorously validating new methods is therefore essential before clinical implementation. The primary objective of the present study was to evaluate the agreement and classification consistency of an AI-assisted fecal egg counting device (Parasight®) relative to the conventional McMaster technique in Kiko male goats, with the aim of assessing its suitability as a screening and clinical decision-support tool. In addition, we evaluated the diagnostic performance of the Parasight® system for identifying animals exceeding the commonly applied therapeutic threshold for Trichostrongylus infection (≥1000 eggs per gram). Finally, we examined the relationship between Parasight® and manual egg counts across multiple sampling times to determine how effectively the automated system captured relative changes in fecal egg burden over time.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Husbandry

A total of 68 male Kiko goats of comparable age were enrolled in the annual University of Florida Buck Test program. At enrollment, the goats had a mean body weight of 25.6 ± 0.51 kg (range: 18.1–34.9 kg), an average body condition score (BCS) of 2.9 ± 0.01 (range: 2.5–3.5), and a mean FAMACHA© score of 1.4 ± 0.01 (range: 1–2). The animals were sourced from multiple external farms and transported to the University of Florida in June 2025, where they were maintained for three months at the Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (IFAS) small ruminant research facility. All goats were group-housed on outdoor pastures under standard husbandry practices, with unrestricted access to Bahiagrass pasture and water. Upon arrival, combination oral anthelmintic treatments (Levamisole 12 mg/kg, Fenbendazole 10 mg/kg, Cydectin 0.4 mg/kg) were administered on day 0 of the test. No anthelmintic treatment was administered during the study period, allowing the natural progression of gastrointestinal nematode infection.

Over the course of the program, each animal underwent seven rounds of FEC evaluation. For the present study, only the final three FECs were included, ensuring that all animals were maintained under identical environmental and management conditions for at least 42 days before the first measurement.

All goats underwent routine bi-weekly health monitoring by University of Florida, College of Veterinary Medicine veterinarians, which included physical examinations, measurement of BCS and body weight, FAMACHA© scoring, measurement of scrotal circumference and fecal sampling for FECs. All goats were maintained under uniform management conditions at the IFAS facility throughout this experiment.

2.2. Animal Selection and Sampling

From the initial population of 68 male Kiko goats enrolled in the University of Florida Buck Test (average age at the start of the program = 143.14 ± 5.2 days), 44 animals were randomly selected for inclusion into this study. Goats were eligible if they were clinically healthy, within the target age range, and maintained under uniform management and nutrition throughout the test period. Animals had not received any anthelmintic or antimicrobial treatment during the test period and showed no evidence of systemic illness, diarrhea, or other clinical abnormalities. Only goats providing a sufficient quantity of fresh feces for analysis, where traceable through individual identification (ear tag), were included. To account for natural variation in body weight, goats were stratified into quartiles (Q1–Q4) based on baseline weights, and 11 goats were randomly chosen from each quartile using a random number generator (Microsoft Excel). The mean (±SEM) body weight in each quartile was: Q1 = 20.23 ± 0.56 kg, Q2 = 24.63 ± 0.25 kg, Q3 = 27.67 ± 0.27 kg, and Q4 = 30.61 ± 0.47 kg. Unique animal IDs and block assignments were recorded. This block-randomization approach ensured a balanced representation across body weight categories and minimized potential bias related to body weight. Due to the lack of fecal sample collection at specific time points, 8, 4, and 12 samples were excluded from the first, second, and third sampling periods, respectively.

Each goat was sampled once every other week for a total of three consecutive time points (T1, T2 and T3), yielding three sampling events per animal. At each time point, a single fecal sample was collected and then divided into two subsamples. One subsample was analyzed using the Parasight® automated egg-counting device, while the other was examined manually by two independent observers using the McMaster technique. Manual observers were blinded to both the Parasight® results and to each other’s counts to minimize observer’s bias. Manual fecal egg counts were performed independently by two licensed veterinarians, each with approximately 10 years of experience in clinical parasitology and laboratory-based diagnostic microscopy. Both observers had extensive prior experience with the McMaster technique in routine clinical and research settings. In addition, they received similar formal training in parasitological diagnostics, as they completed their veterinary education together and subsequently underwent comparable postgraduate training. This shared educational and professional background ensured consistency in egg identification and counting procedures and strengthened the reliability of the manual McMaster method used as the reference standard in this study.

Immediately after collection, fecal samples were placed in a cooler (≈4 °C) and subsequently stored under refrigeration until analysis. All manual McMaster counts were completed within 6 days of collection, with samples maintained at 4 °C throughout the storage period. This time window was chosen because refrigerated fecal egg counts are reported to remain relatively stable for approximately one week, whereas detectability begins to decline when refrigeration extends beyond ~8 days [

16]. Additionally, both manual observers read slides concurrently to avoid differences in slide quality or sample condition due to processing time.

All fecal egg counts were expressed as eggs per gram (EPG) of feces. In addition, technicians responsible for sample handling were blinded to sample identity to ensure objectivity throughout the study.

2.3. Egg Counting Methods

Each fecal sample was divided into two equal portions: one designated for manual McMaster counting and the other for analysis using Parasight

® system (Parasight System Inc., Lexington, KY, USA). From the portion assigned to the manual McMaster method, two replicate slides were prepared and examined independently to account for within-sample variability and ensure counting precision. Fecal egg counts were performed using the modified McMaster technique as previously described [

17]. Briefly, approximately 2 g of fresh feces was homogenized with 28 mL of saturated salt flotation solution (specific gravity ~1.20). The suspension was strained through a tea strainer to remove large debris, and each chamber of a McMaster slide (0.15 mL per chamber) was carefully filled with filtration. Slides were allowed to stand for ~5 min to permit egg flotation and then examined under a compound microscope at 100× magnification. Strongyle-type eggs (

Haemonchus contortus,

Ostertagia spp.,

Trichostrongylus spp.,

Cooperia sp.),

Moniezia spp. and

Strongyloides spp. were counted by the two observers within the ruled grid areas of both chambers to obtain fecal egg counts.

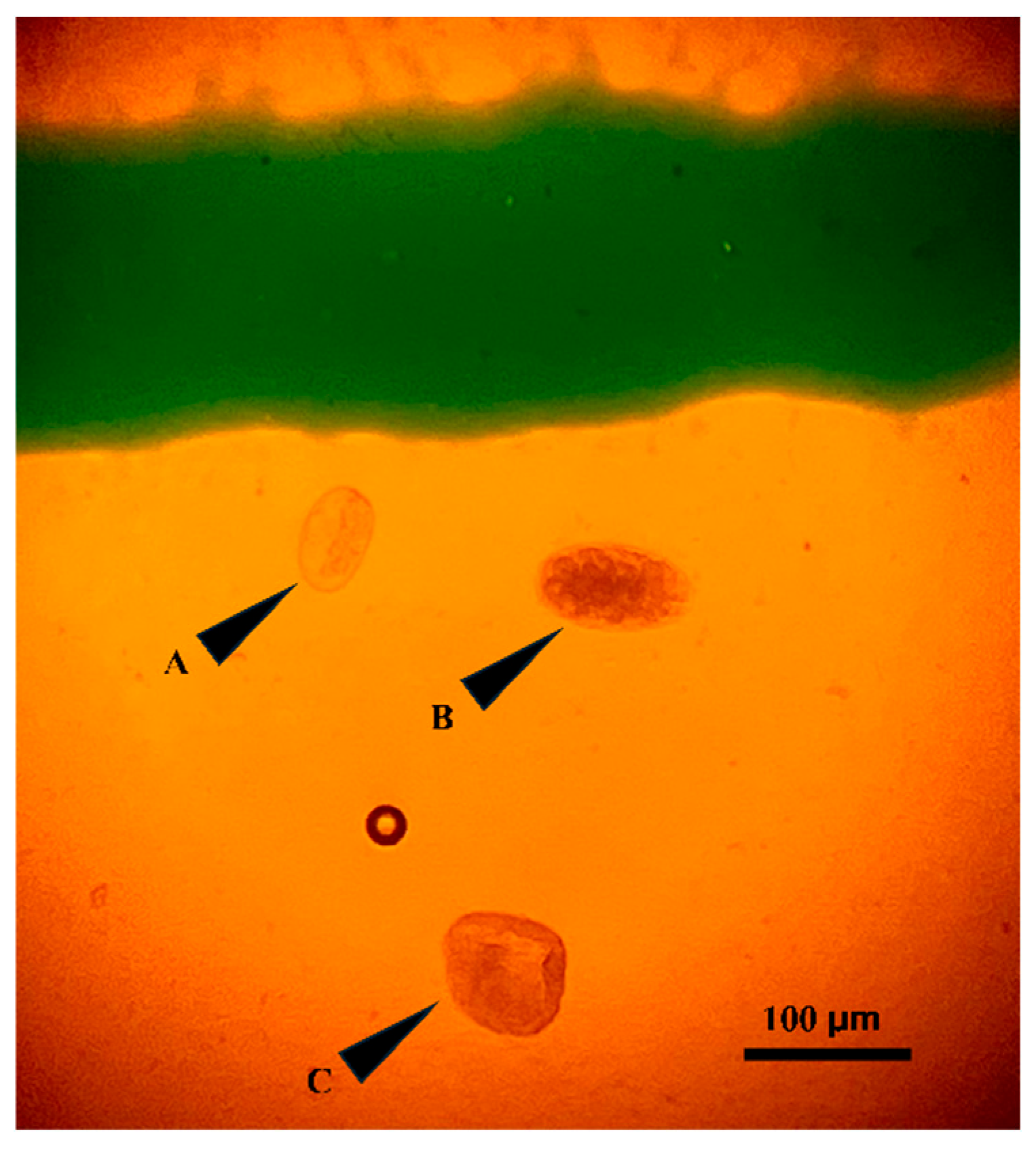

Figure 1. Representative micrographs of an example of the three nematode egg types identified in goat fecal samples. The total number of eggs was multiplied by 50 to obtain eggs per gram. To ensure consistency, all slides were read within 60 min of preparation, and fecal samples were stored at 4 °C and processed within 6 days of collection. The sensitivity of the method was 50 EPG.

Automated FECs were performed with a commercial system (Parasight

® powered by FecalsightAI™; MEP Equine Solutions, Lexington, KY, USA) which concentrates eggs by filtration, fluorescently labels them, and enumerates them using automated imaging and a deep-learning classifier, following the fluorescence-based approach described by [

15]. Detailed proprietary implementation is not publicly disclosed.

2.4. Sample Size Calculation

To evaluate the agreement between the Parasight

® automated egg-counting device and the manual McMaster method, the concordance correlation coefficient (CCC) method was implemented and sample size was determined using the Lin’s method [

18] which estimates the number of subjects needed to detect a meaningful difference between an expected CCC and a null value at a specified significance level and power. We assumed an expected CCC of 0.80, representing good agreement based on conventional thresholds, and a minimum acceptable (null) value of 0.60. With a two-sided alpha of 0.05 and 80% power, the required sample size was 40 animals. To account for potential sample loss, we increased enrollment by 10%, resulting in a final study population of 44 animals. Fecal egg shedding in small ruminants can fluctuate over time due to environmental factors, and physiological stressors, therefore we incorporated three sampling times spaced two weeks apart to improve the reliability of our evaluation. Multiple sampling timepoints allowed us to assess the temporal consistency of agreement between methods and to capture potential differences in method performance across varying parasite burdens. This design also ensured that both the manual and automated methods were evaluated under conditions of low, moderate, and high egg counts, thereby providing a more comprehensive assessment of agreement across the full biologically relevant range of fecal egg shedding.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software (version 4.3.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). To test consistency among manual observers, the intraclass correlation coefficient (

ICC) measurement was used for each of the samples in three sampling times separately for each parasite egg related to

Trichostrongylus,

Moniezia,

Strongyloides and Total EPG is the sum of

Trichostrongyle spp.,

Strongyloides and

Moniezia. A two-way random-effects model with absolute agreement was applied, and ICC values were reported with 95% confidence intervals. Interpretation followed standard benchmarks that includes values < 0.50 = poor, 0.50–0.75 = moderate, 0.75–0.90 = good, and >0.90 = excellent reliability [

19]. Agreement between observers was further evaluated using Bland–Altman analysis, reporting mean bias and 95% limits of agreement.

To compare the Parasight® automated device with manual McMaster reference, the reference value was calculated as the average of the two observers’ counts for each sample and time point. This agreement was assessed for Trichostrongyle, Strongyloides and Total EPG (the current configuration of the Parasight® device is limited to detecting and counting Trichostrongylus and Strongyloides eggs only) which is sum of Trichostrongyle and Strongyloides using Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient. To address the right-skewed distribution typically observed in fecal egg count data, log transformation was initially explored during preliminary analyses; however, agreement statistics presented in the final tables were computed on the original EPG scale to allow direct interpretation of absolute differences between methods. Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for CCC were obtained using the epi.ccc() function (epiR package, version 4.3.2), and the bias correction factor (Cb) was reported to quantify scale and location shift. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was additionally computed to assess monotonic association.

Bland–Altman analyses were performed on the original EPG scale to quantify absolute disagreement between Parasight

® and manual McMaster counts. In this framework, mean bias represents the average difference in EPG (Parasight

®—manual), and the limits of agreement (LoA) describe the range within which most measurement differences are expected to fall. This approach provides a direct interpretation of numerical under- or overestimation in biologically meaningful units. Initial exploratory analyses was performed on log-transformed data to evaluate proportional disagreement. In order to allow for comparison with

Table 1 and to maintain consistency with the manual method’s measurement scale,

Table 2 represents the final results in the original EPG scale after back-transformation. Observer agreement on categorical classification of

Trichostrongylus egg counts (>1000 vs. ≤1000 EPG) was assessed with Cohen’s κ, interpreted as: ≤0.20 = slight, 0.21–0.40 = fair, 0.41–0.60 = moderate, 0.61–0.80 = substantial, and ≥0.81 = almost perfect agreement [

20]. For categorization of the continued measures of FECs of

Trichostrongylus, we used the cut off 1000 EPG of parasite eggs to consider it as a clinical infection in goats. However, it is worth mentioning that no single universal threshold has been set for

Trichostrongylus and not all the thresholds can apply to all situations. General guidelines suggest treating goats with FECs above 200 EPG with treatment becoming necessary for higher counts such as 500 EPG. However, the most important factor which determines the treatment is clinical signs of the disease which indicate the animals with high FEC, combined with clinical signs, to be targeted for clinical treatment.

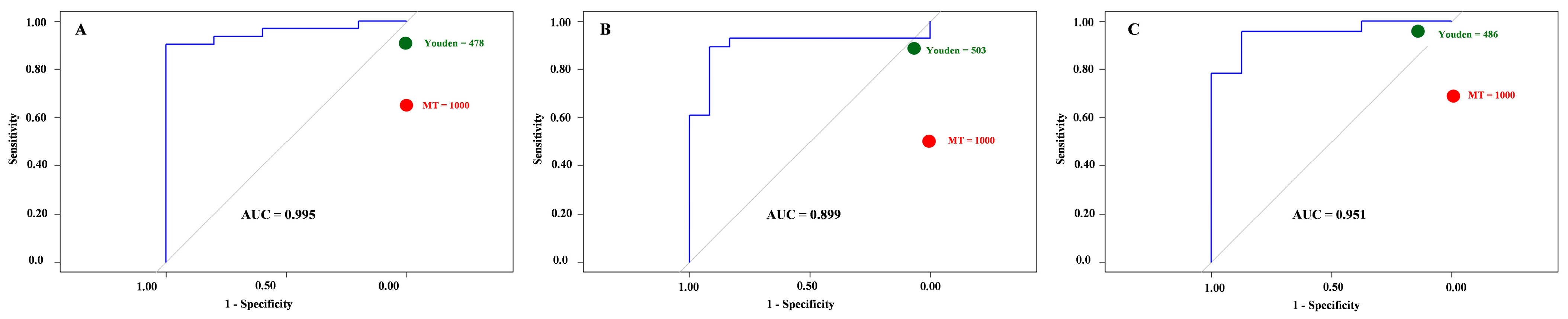

The diagnostic performance of the Parasight

® device relative to the manual McMaster method was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (

ROC) analysis. The average classification from the two manual observers (>1000 vs. ≤1000 eggs per gram [EPG]) served as the reference standard, and Parasight

® counts were treated as the continuous predictor. An area under the curve (

AUC) of 0.5 indicates a non-informative test (equivalent to random classification), whereas an AUC of 1.0 represents perfect discrimination. Test accuracy was interpreted as follows: 0.90–1.00 = excellent, 0.70–0.89 = acceptable, and <0.70 = poor [

21]. The optimal Parasight

® cutoff value was determined by maximizing Youden’s J statistic (sensitivity + specificity − 1). Diagnostic performance was further evaluated at the clinical decision threshold of 1000 EPG, with sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (

PPV), and negative predictive value (

NPV) reported. All ROC analyses were conducted separately for each sampling time point (T1–T3).

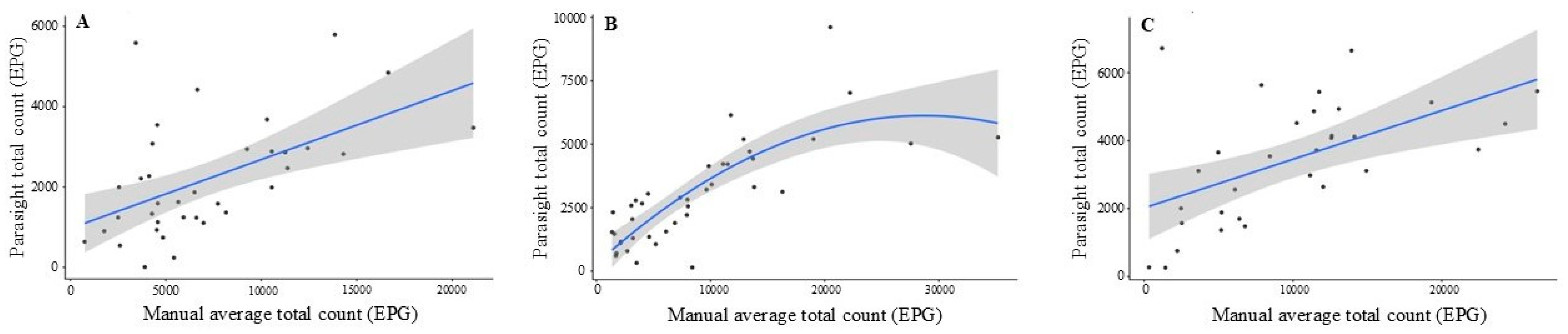

Regression analyses were conducted separately for each sampling time to evaluate the association between Parasight® total egg counts and the manually derived total egg counts (average of two observers at each time point). For each timepoint, linear and quadratic variables (Manual + Manual2) were initially fitted, and the quadratic term was retained only when its contribution was statistically significant (p ≤ 0.10).

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to evaluate the performance of an AI-assisted fluorescence imaging system (Parasight

® automated device) for fecal egg counting in Kiko goats, using the conventional McMaster method as the reference standard. As a foundational step, inter-observer reliability of the manual McMaster technique was assessed to establish a robust benchmark for comparison. Overall, the two observers demonstrated consistently high agreement across all sampling times, particularly for

Trichostrongyle and

Moniezia counts, confirming the reliability of the McMaster method as a gold-standard approach for fecal egg quantification. The McMaster method is currently recommended for use in veterinary practice as a simple and user-friendly method [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. The Bland–Altman plots (

Figure 2A–C) visually reinforced this strong concordance, showing minimal systematic bias and narrow limits of agreement between observers. These findings indicate that the manual method produces repeatable results under controlled conditions, with only minor dispersion at higher egg concentrations where counting precision typically declines. Cohen’s Kappa analysis of categorical classification (≤1000 vs. >1000 EPG) further supported this conclusion. Agreement between the two observers was perfect at T1, almost perfect at T2, and substantial at T3, with raw agreement consistently exceeding 90%. These findings confirm that both manual observers were highly consistent not only in quantitative enumeration but also in clinical classification of infection levels. Across all three sampling times, ICCs consistently reflected good agreement between observers, supporting the reproducibility of manual counting under controlled conditions. Nevertheless, Bland–Altman analysis revealed a more nuanced picture: while mean biases were modest (ranging from +749 to +1626 EPG), the limits of agreement were wide (up to −7962 to +11,106 EPG). This indicates that although observers tended to rank samples similarly, absolute discrepancies between counts could still be biologically relevant. The total EPG values can thus be viewed as an aggregate in which the variability of

Trichostrongyle and

Strongyloides components becomes amplified. High variability in the FECs has been reported previously (Carstensen et al., 2013) [

23] and the effect of reducing sample processing time as a source of human error has been documented previously [

14]. However, in this study there was no time limitation that would force the manual observer to have errors related to the shortness of time budget. Together, these results demonstrate that the McMaster method provides reliable inter-observer consistency, but its precision naturally declines as egg concentrations increase. This finding highlights the intrinsic variability of manual microscopy that must be considered when validating automated alternatives.

When comparing the Parasight

® automated fluorescence-imaging device with the manual McMaster method, the agreement was variable across sampling times and parasite groups. Lin’s CCC ranged from poor to moderate, indicating limited absolute agreement between the two methods. The strongest concordance was observed for

Trichostrongyle eggs at T3, while

Strongyloides and total EPG values showed lower levels of agreement. Despite these modest CCC values, the corresponding Spearman’s rank correlations were moderate to high, suggesting that Parasight

® automated device effectively captured the relative ranking of infection intensities, even when absolute counts diverged from the manual reference. A previous study [

14] has shown a strong linear correlation between automated and McMaster counts (R

2 ≈ 0.93); however, correlation primarily reflects association rather than full agreement. Similarly, earlier work by Slusarewicz et al., (2016) [

15] demonstrated the feasibility of using fluorescent chitin-binding probes and smartphone-based imaging for parasite egg enumeration, showing a strong linear relationship with manual McMaster counts (R

2 ≈ 0.93–0.98) and improved precision through automated image analysis. However, that study primarily assessed correlation and technical performance rather than full analytical agreement. In the present study, we extended this evaluation by assessing both precision and accuracy using Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient and Bland–Altman analysis

Results of the Bland–Altman analysis provided further insight into the pattern of disagreement between the two methods. Across all sampling times, the Parasight

® automated device consistently underestimated fecal egg counts relative to the manual McMaster technique, with mean percentage biases ranging from −48% to −82%. The 95% limits of agreement were wide, particularly at lower egg concentrations, reflecting greater variability in low-count samples. Nevertheless, most observations fell within these limits, indicating that although systematic underestimation occurred, the magnitude of disagreement remained within a diagnostically acceptable range. Similar tendencies have been reported in previous studies evaluating automated FEC technologies, where differences in flotation media, image-processing thresholds, and egg-recognition algorithms influenced count outcomes. A recent study in sheep [

24] demonstrated that a fluorescence-AI platform can rapidly quantify the percentage of

Haemonchus contortus with both strong correlation and Lin’s concordance relative to manual fluorescence microscopy and coproculture (R

2 ≈ 0.82–0.88; qc ≈ 0.86–0.94), albeit with a subtle tendency toward lower automated percentages. These results support the broader feasibility of fluorescence-based automation. Our study complements this literature by evaluating absolute fecal egg counts in goats and by quantifying agreement with both Lin’s CCC and Bland–Altman limits. Taken together, our analyses suggest that Parasight

® automated device is promising, while also underscoring the value of method-specific calibration for clinical decision making.

Categorical agreement between the Parasight® automated device and the average of the two manual observers was also evaluated to assess consistency in diagnostic classification. At T1 and T2, agreement was fair, with raw agreements of 69.4% and 65.0%. At T3, the level of agreement improved to moderate. These results indicate that although Parasight® automated device tended to misclassify some samples near the clinical threshold, primarily underestimating those above 1000 EPG. Collectively, the continuous and categorical analyses demonstrate that the Parasight® automated device reproduced overall infection trends and rankings observed with the manual McMaster method, but systematic underestimation reduced exact numerical and categorical alignment. To our knowledge, this is the first evaluation of categorical agreement (≤1000 vs. >1000 EPG) between an automated fluorescence-AI system and the manual McMaster reference. Calibration of diagnostic thresholds is therefore warranted to ensure equivalence in treatment decision-making.

Across all sampling times, ROC analysis demonstrated that the Parasight® device achieved excellent overall discrimination when benchmarked against the manual McMaster reference (AUC = 0.90–0.96). Despite this strong diagnostic capacity, the device consistently underestimated egg counts, a trend also evident in Bland–Altman and concordance analyses. This systematic underestimation primarily affected samples near the clinical threshold of 1000 EPG, leading to reduced sensitivity when the manual cutoff was directly applied. At this threshold, specificity and positive predictive value remained at 100%, indicating that Parasight® device rarely overestimated or falsely classified negatives as positives. However, sensitivity declined from 89 to 96% at the optimized cutoff (~480–500 EPG) to 50–70% when using the fixed manual threshold, resulting in lower negative predictive values (31–53%).

Regression analyses provided additional insight into the relationship between Parasight® device and manual McMaster counts beyond agreement metrics. While concordance and Bland–Altman analyses evaluate absolute equivalence, regression characterizes how changes in manual egg counts are reflected in the automated system. At T1 and T3, the relationship between the two methods was best described by a linear model, indicating that Parasight® device counts increased proportionally with manual counts, albeit at a reduced magnitude (0.14–0.17 EPG increase per 1 EPG increase manually). These shallow slopes support the consistent underestimation observed in the Bland–Altman plots and demonstrate that although Parasight® device tracked directional changes in egg burden, it systematically produced lower absolute values across the observed range. In contrast, T2 exhibited a significant quadratic pattern, with a steep initial increase and progressive flattening at higher egg concentrations. This curvilinear trend likely reflects partial sensor or algorithmic saturation under high parasite loads, a phenomenon also described in prior evaluations of automated FEC platforms. The strong model fit at T2 (R2 = 0.66), compared with more modest fits at T1 and T3 (R2 ≈ 0.29–0.30), suggests that the device performed most consistently when egg counts were moderate and more variable at low or extremely high burdens. Collectively, these regression findings indicate that the Parasight® device reliably captured relative differences in fecal egg shedding but exhibited non-proportional scaling and reduced accuracy as egg burdens increased, further reinforcing the need for method-specific calibration before applying manual diagnostic thresholds to automated outputs.

These findings collectively indicate that Parasight® device captures the directional trend and relative infection intensity reliably, but due to undercounting bias, the same treatment threshold cannot be directly transferred from manual to automated readings. Adjusting the operational cutoff to approximately 480–500 EPG would restore diagnostic equivalence to manual classification and minimize false negatives while maintaining high specificity. Importantly, this pattern was consistent across all three sampling periods, reflecting stable device performance under field conditions. Overall, this study demonstrates that the Parasight® AI-assisted fluorescence imaging system provides a robust, objective, and reproducible approach for fecal egg counting in goats, with excellent ability to rank parasite burden and discriminate animals above the clinical treatment threshold. However, systematic underestimation of egg counts relative to the manual McMaster method resulted in poor-to-moderate absolute agreement and reduced sensitivity when conventional thresholds were applied directly. These findings indicate that Parasight® is best suited as a calibrated decision-support or screening tool rather than a direct numerical replacement for manual counts. Importantly, adjusting the operational cutoff restored diagnostic equivalence with manual classification, supporting its practical use in targeted selective treatment programs. From a clinical perspective, this calibration-based approach can reduce labor demands and observer variability while maintaining appropriate treatment decisions. Future research should focus on external validation across diverse production systems, assessment of within-device repeatability, and refinement of algorithmic scaling to improve absolute agreement across the full range of parasite burdens.

The findings of this study should be interpreted considering both the inherent limitations of the McMaster FEC method and those of evaluating a proprietary automated diagnostic platform. The McMaster technique has limited analytical sensitivity, does not differentiate parasite species within strongyle-type eggs, and provides a single time-point estimate that can be influenced by egg-shedding variability, animal physiology, and environmental factors [

17]. Such biological and methodological variability likely contributed to part of the disagreement observed between the manual and automated methods. In addition, the Parasight

® system was evaluated as a fixed, commercially deployed algorithm, and its internal model architecture and training process are not publicly disclosed, limiting deeper assessment of algorithm-level sources of bias. Repeatability of the Parasight

® device itself was not directly evaluated in this study, as each sample was processed once to reflect routine clinical use; therefore, within-device precision could not be quantified. The consistently low Lin’s concordance correlation coefficients observed are best interpreted as reflecting systematic scale and location bias, primarily underestimation by the automated system, rather than poor association, as supported by moderate-to-high rank correlations, strong diagnostic discrimination, and coherent regression patterns. Finally, the absence of an independent external validation dataset represents an additional limitation, and future studies incorporating replicate automated measurements and multi-farm validation cohorts will be essential to fully characterize precision, robustness, and generalizability of automated fecal egg counting systems.