Knowledge, Perception, and Practices of Wildlife Conservation and Biodiversity Management in Bangladesh

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Informed Consent and Confidentiality

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Survey and Questionnaires

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Respondent

3.2. Public Knowledge About Biodiversity of Wild Animal Species

3.3. Knowledge About Wildlife and Biodiversity

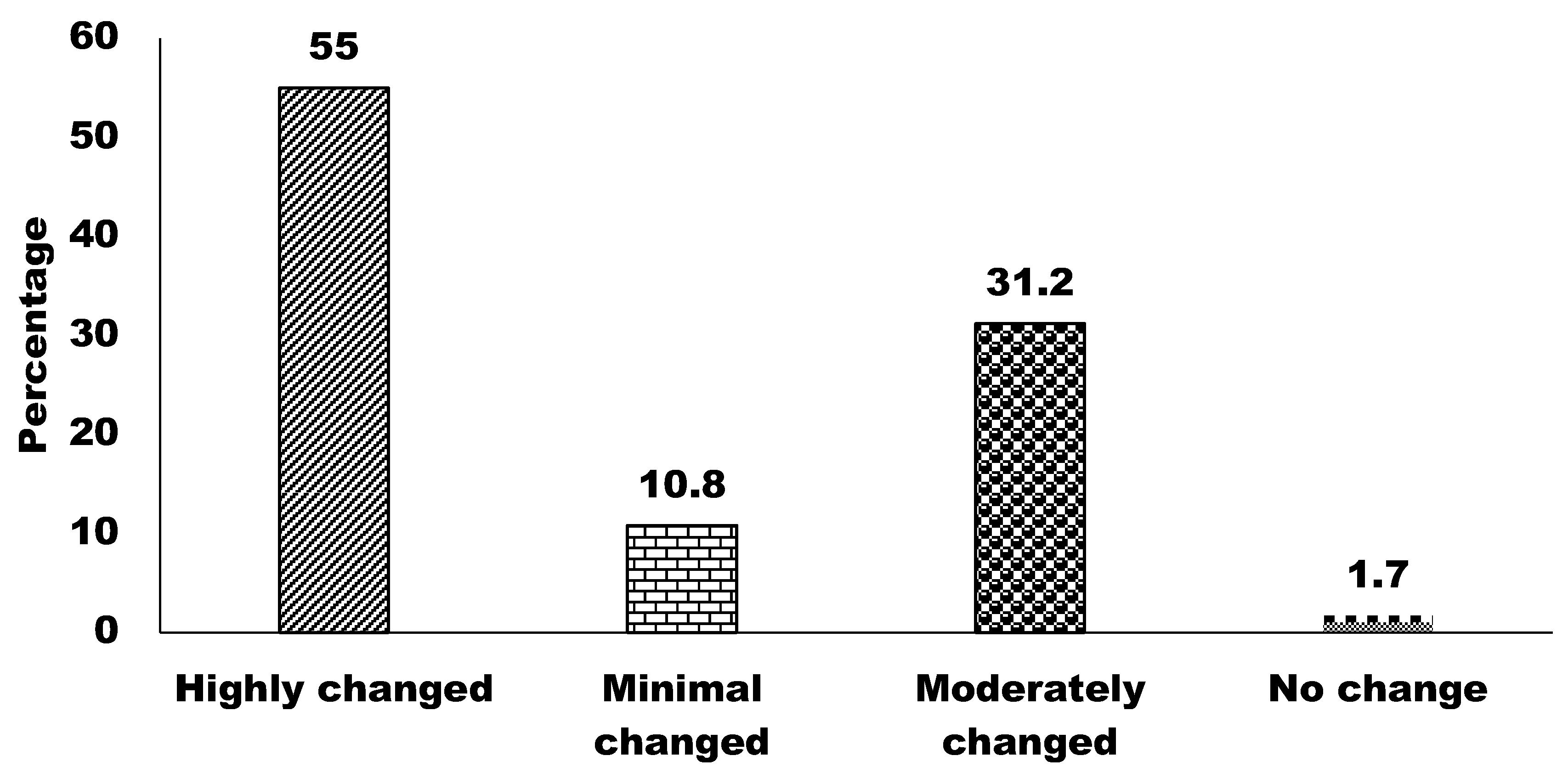

3.4. Changes in Wildlife Habitats in Bangladesh

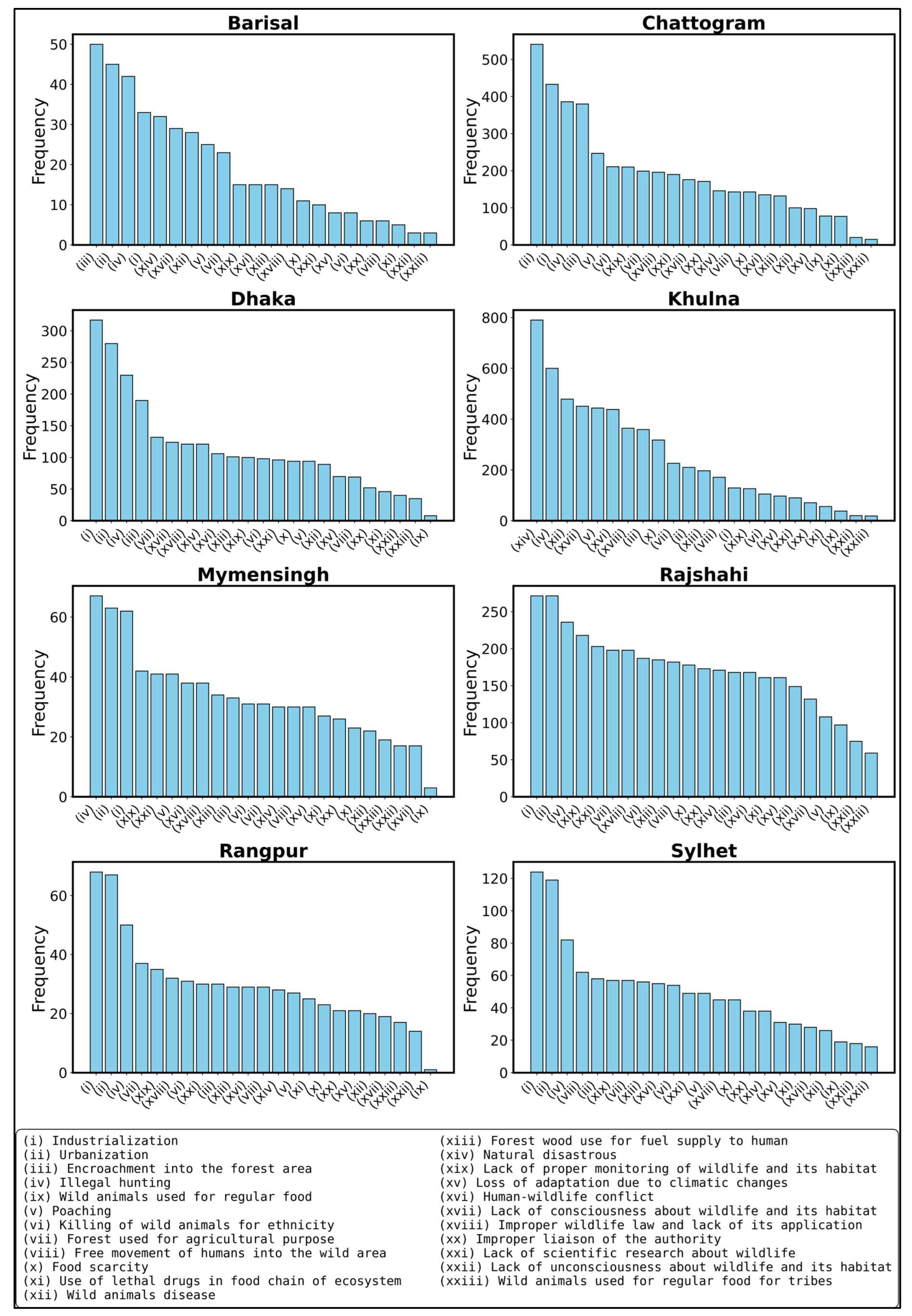

3.5. Perception of Causes of Destruction of Wildlife Habitat and Biodiversity in Bangladesh

3.6. Strategies to Avoid Human-Wildlife Conflict

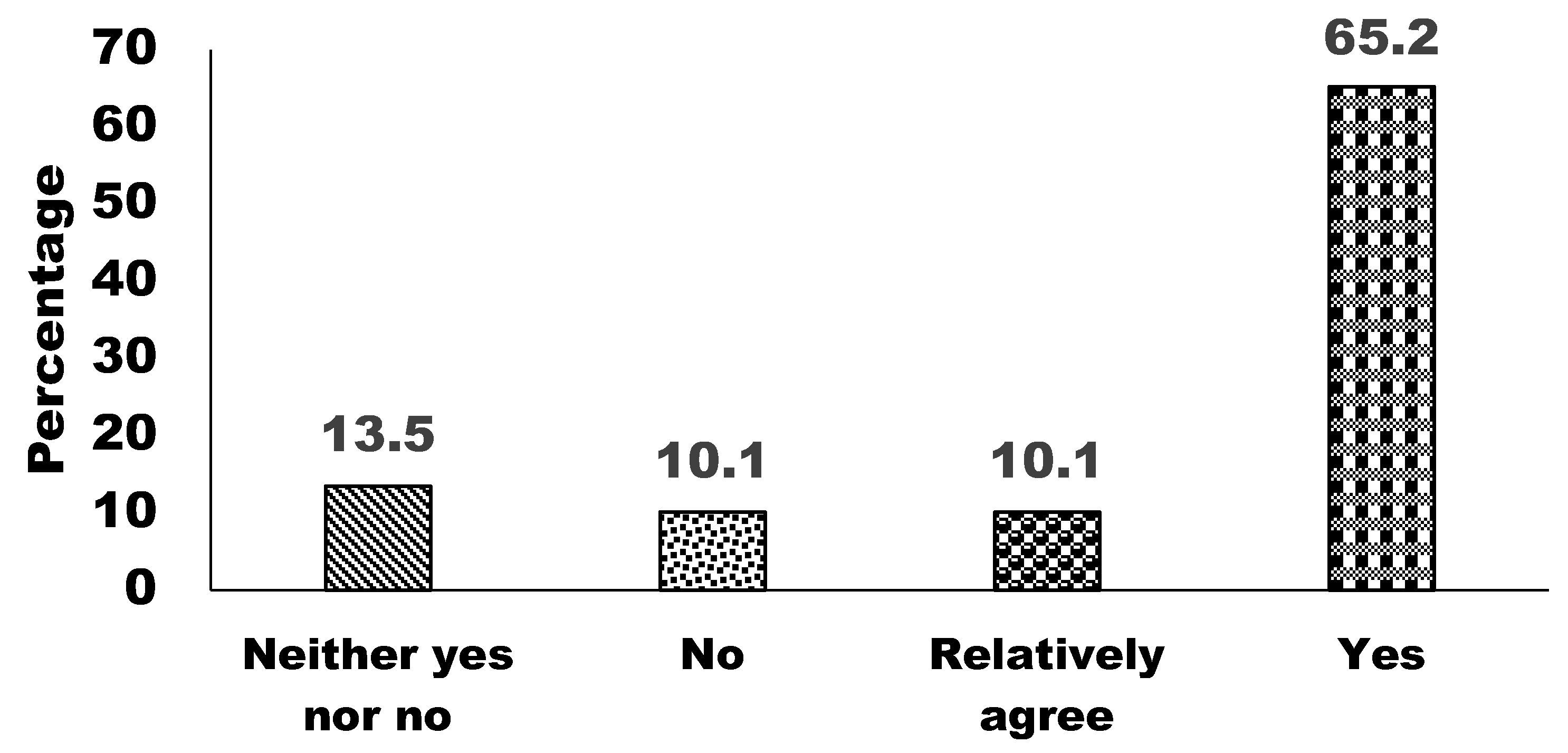

3.7. Perceptions of the Balance Between Humans and Wildlife

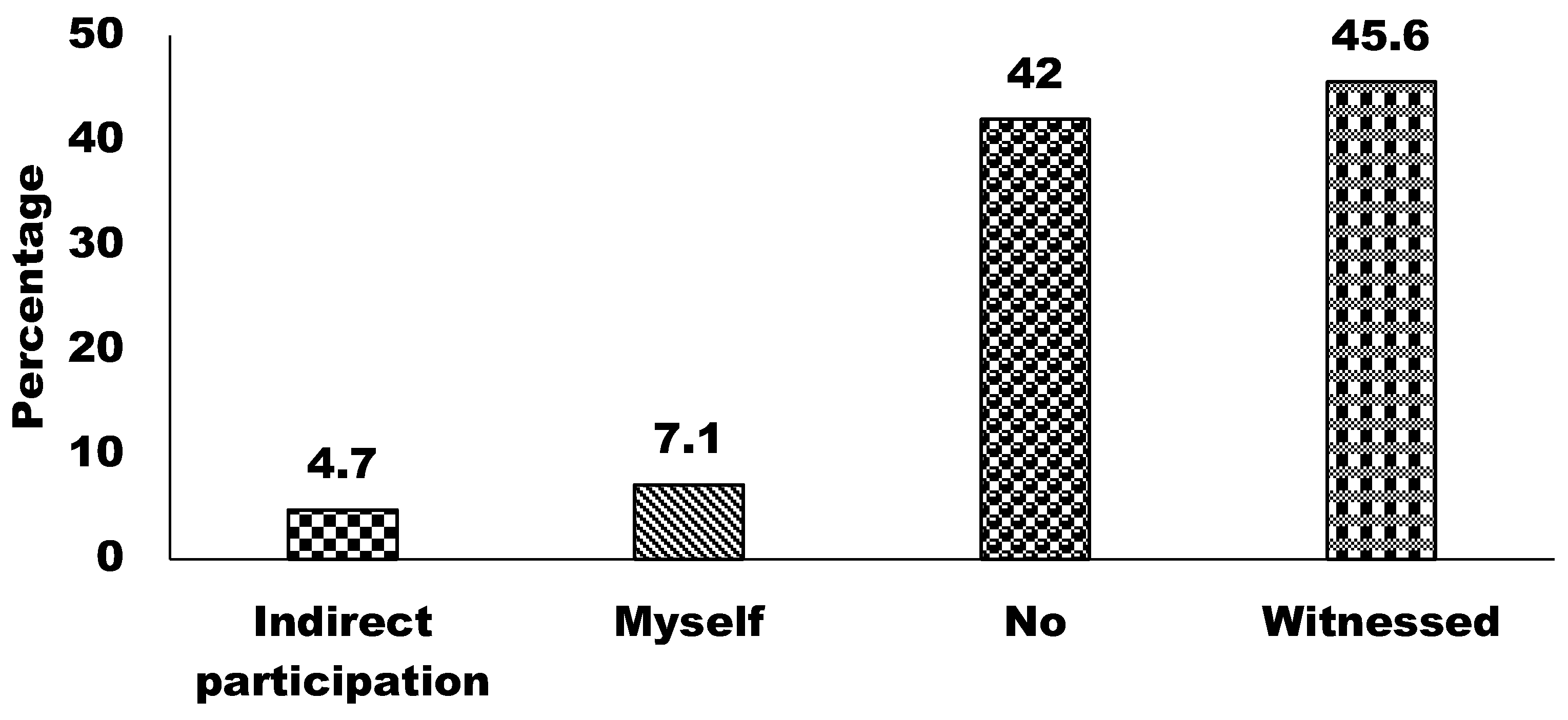

3.8. Practice in Wildlife Hunting

3.9. Public Perception of Wildlife Hunting and Trade

3.10. Association Between Sociodemographic Factors and Levels of KPP

3.11. Differences in KPP

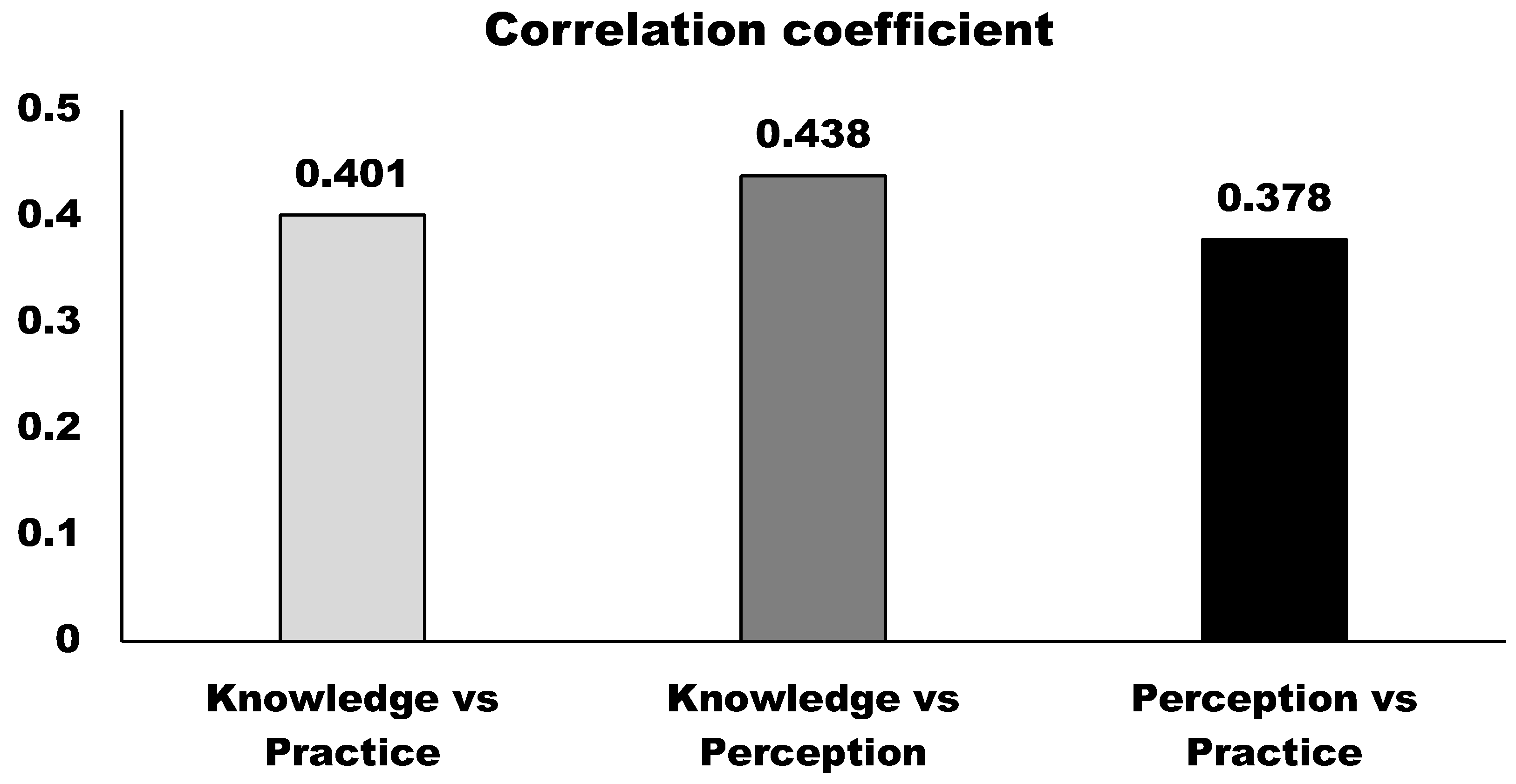

3.12. Correlation Analysis Between KPP

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oommen, M.A.; Cooney, R.; Ramesh, M.; Archer, M.; Brockington, D.; Buscher, B.; Fletcher, R.; Natusch, D.J.D.; Vanak, A.T.; Webb, G. The fatal flaws of compassionate conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2019, 33, 784–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, N.J.; Roth, R.; Klain, S.C.; Chan, K.; Christie, P.; Clark, D.A.; Cullman, G.; Curran, D.; Durbin, T.J.; Epstein, G.; et al. Conservation social science: Understanding and integrating human dimensions to improve conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 205, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengistu, F.; Assefa, E. Towards sustaining watershed management practices in Ethiopia: A synthesis of local perception, community participation, adoption and livelihoods. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 112, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.J. Using perceptions as evidence to improve conservation and environmental management. Conserv. Biol. 2016, 30, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montana, M.; Mlambo, D. Environmental awareness and biodiversity conservation among resettled communal farmers in Gwayi Valley Conservation Area, Zimbabwe. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2019, 26, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, B. Human-wildlife conflicts and the need to include tolerance and coexistence: An introductory comment. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2016, 29, 738–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Huitrón, N.M.; Naranjo, E.J.; Santos-Fita, D.; Estrada-Lugo, E. The Importance of Human Emotions for Wildlife Conservation. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butchart, S.H.; Walpole, M.; Collen, B.; van Strien, A.; Scharlemann, J.P.; Almond, R.E.; Baillie, J.E.; Bomhard, B.; Brown, C.; Bruno, J.; et al. Global biodiversity: Indicators of recent declines. Science 2010, 328, 1164–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trisos, C.H.; Merow, C.; Pigot, A.L. The projected timing of abrupt ecological disruption from climate change. Nature 2020, 580, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAlpine, C.; Catterall, C.P.; Nally, R.M.; Lindenmayer, D.; Reid, J.L.; Holl, K.D.; Bennett, A.F.; Runting, R.K.; Wilson, K.; Hobbs, R.J.; et al. Integrating plant- and animal-based perspectives for more effective restoration of biodiversity. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silaeva, T.; Andreychev, A.; Kiyaykina, O.; Balčiauskas, L. Taxonomic and ecological composition of forest stands inhabited by forest dormouse Dryomys nitedula (Rodentia: Gliridae) in the Middle Volga. Biologia 2021, 76, 1475–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, F.S., 3rd; Zavaleta, E.S.; Eviner, V.T.; Naylor, R.L.; Vitousek, P.M.; Reynolds, H.L.; Hooper, D.U.; Lavorel, S.; Sala, O.E.; Hobbie, S.E.; et al. Consequences of changing biodiversity. Nature 2000, 405, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.M.; Amin, A.S.M.R.; Sarker, S.K. National report on alien invasive species of Bangladesh. In Invasive Alien Species in South-Southeast Asia: National Reports & Directory of Resources; Pallewatta, N., Reaser, J.K., Gutierrez, A.T., Eds.; Global Invasive Species Programme (GISP): Cape Town, South Africa, 2003; pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, J.S.; Waylen, K.A.; Mulder, M.B. How national context, project design, and local community characteristics influence success in community-based conservation projects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 21265–21270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; da Fonseca, G.A.B.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faroque, S.; Nigel, S. Law-Enforcement challenges, responses and collaborations concerning environmental crimes and Harms in Bangladesh. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2020, 66, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, Z. TK10 Crore Traded in Wildlife Trafficking a Year. The Business Standard. 2020. Available online: https://www.tbsnews.net/bangladesh/crime/TK10-crore-traded-wildlife-trafficking-year-35599 (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- Montero, M.; Wright, J.J.; Khan, E.M.; Najeeb, M. Illegal logging, fishing, and wildlife trade: The costs and how to combat it. World Bank Group 2019, 143758, 70. [Google Scholar]

- Mattson, D.; Logan, K.; Sweanor, L. Factors governing risk of cougar attacks on humans. Hum. Wildl. Interact. 2011, 5, 135–158. [Google Scholar]

- Hossen, A.; Røskaft, E. A case study on conflict intensity between humans and elephants at Teknaf Wildlife Sanctuary, Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2023, 4, 1067045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shazali, A.G.; Mayele, J.M.; Saburi, J.E.; Nadlin, J. Evaluating the impacts of human activities on diversity, abundance, and distribution of large mammals in Nimule National Park, South Sudan. Open J. Ecol. 2024, 14, 483–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Plas, F. Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning in naturally assembled communities. Biol. Rev. 2019, 94, 1220–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizina, Y.; Kobei, D. Indigenous peoples and sustainable wildlife management in the global era. Unasylva 2017, 68, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.M.H. Ecology and Conservation of the Bengal Tiger in the Sundarbans Mangrove Forest of Bangladesh. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chakma, S. Assessment of Large Mammals of the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh with Emphasis on Tiger Panthera Tigris. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Zoology, University of Dhaka, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, M.A.; Feeroz, M.M.; Hasan, M.K. Human-wildlife conflict in Bangladesh: Species, extent, and management practices. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2013, 18, 174–184. [Google Scholar]

- Basir, N.S.; Ming, W.L. The role of governmental and non-governmental organizations in environmental conservation. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 232, 483–491. [Google Scholar]

- Kioko, J.M.; Kiringe, J. Youth’s knowledge, attitudes and practices in wildlife and environmental conservation in Maasailand, Kenya. South. Afr. J. Environ. Educ. 2010, 27, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Snyman, S.L. The role of tourism employment in poverty reduction and community perceptions of conservation and tourism in southern Africa. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 395–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, R.M.; Sarker, S.U.; Rahman, M.M. Cultural perspectives on wildlife conservation: Insights from rural Bangladesh. Ecol. Manag. Conserv. 2015, 20, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Mariki, S.B. Pupils’ awareness and attitudes towards wildlife conservation in two districts in Tanzania. Asian J. Humanit. Soc. Stud. 2016, 4, 142–150. [Google Scholar]

- Afriyie, J.O.; Asare, M.O.; Hejcmanová, P. Exploring the Knowledge and Perceptions of Local Communities on Illegal Hunting: Long-Term Trends in a West African Protected Area. Forests 2021, 12, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oražem, V.; Smolej, T.; Tomažič, I. Students attitudes to and knowledge of brown bears (Ursus arctos L.): Can more knowledge reduce fear and assist in conservation efforts? Animals 2021, 11, 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukul, S.A.; Uddin, M.B.; Rahman, M.A. Integrating community knowledge and scientific approaches for sustainable wildlife conservation in Bangladesh. Conserv. Sci. 2017, 5, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.K.; Mukul, S.A.; Sohel, M.S.I. Forest conservation strategies and the role of local communities in Bangladesh. For. Policy Econ. 2022, 134, 102613. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; van der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinney, W. Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 28 June–3 July 2010; pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Waskom, M.L. Seaborn: Statistical Data Visualization. J. Open Source Softw. 2021, 6, 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GADM. Database of Global Administrative Areas. Version 4.1. 2023. Available online: https://gadm.org (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Chowdhury, S.; Alam, S.; Labi, M.M.; Khan, N.; Rokonuzzaman, M.; Biswas, D.; Tahea, T.; Mukul, S.A.; Fuller, R.A. Protected areas in South Asia: Status and prospects. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 811, 152316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, S. Threatened species could be more vulnerable to climate change in tropical countries. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 159989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.M.H. Protected areas of Bangladesh: A Guide to Wildlife; Nishorgo Program, Wildlife Management and Nature Conservation Circle; Bangladesh Forest Department: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Feeroz, M.M.; Hasan, M.K.; Khalilullah, M.I. Nocturnal terrestrial mammals of Teknaf Wildlife Sanctuary, Bangladesh. Zoo’s Print 2012, 27, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN Bangladesh. Red List of Bangladesh Volume 1: Summary; IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, Bangladesh Country Office: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2015; pp. xvi+122. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.K. Overview of the forest biodiversity in Bangladesh. In Assessment, Conservation and Sustainable Use of Forest Biodiversity; CBD Technical Series No. 3; Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2001; pp. 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.R. Causes of biodiversity depletion in Bangladesh and their consequences on ecosystem services. Am. J. Environ. Prot. 2015, 4, 214–236. [Google Scholar]

- Mollah, A.R.; Rahaman, M.M.; Rahman, M.S. Site level field appraisal for protected area co management: Teknaf Game Reserve. In Nature Conservation Management (NACOM); Nishorgo Publication: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2004; pp. 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- DeCosse, P.J.; Roy, M.K. Do the Poor Win or Lose When We Conserve Our Protected Areas? Nishorgo Publication: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2005; pp. 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Getachew, T.; Barihun, G.E.C. Method of Conservation of the Ecosystem and Biodiversity in Ethiopia; Ecosystem and Biodiversity Richness, Protecting and Research Institution: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 1996; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, M.S.H.; Gudmundsson, C.; Izumiyama, S.; Koike, M.; Nazia, N.; Rana, M.P.; Mukul, S.A.; Muhammed, N.; Redowan, M. Community attitudes toward forest conservation programs through collaborative protected area management in Bangladesh. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2014, 16, 1235–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, J.N.; Heinen, J.T. Does community-based conservation shape favorable attitudes among locals? An empirical study from Nepal. Environ. Manag. 2001, 28, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Bhagwat, S.A. Protected areas: A resource or constraint for local people? A study at Chitral Gol National Park, North-West Frontier Province, Pakistan. Mt. Res. Dev. 2010, 30, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisiforou, O.; Charalambides, A.G. Assessing undergraduate university students’ level of knowledge, attitudes, and behavior towards biodiversity: A case study in Cyprus. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2012, 34, 1027–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roskaft, E.; Bjerke, T.; Kaltenborn, B.; Linnell JD, C.; Andersen, R. Patterns of self-reported fear towards large carnivores among the Norwegian public. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2003, 24, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltenborn, B.P.; Bjerke, T.; Nyahongo, J. Living with problem animals: Self reported fear of potentially dangerous species in the Serengeti region, Tanzania. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2010, 11, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokop, P.; Tunnicliffe, S.D. Effects of keeping pets on children’s attitudes toward popular and unpopular animals. Anthrozoös 2010, 23, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, M.J.; Roque de Pinho, J.; Perry, J. Maintaining complex relations with large cats: Maasai and lions in Kenya and Tanzania. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2010, 15, 332–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Osborn, F.; Plumptre, A.J. Confict of interest between people and baboons, crop raiding in Uganda. Int. J. Primatol. 2000, 21, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treves, A. Balancing the Needs of People and Wildlife: When Wildlife Damage Crops and Prey on Livestock; University of Wisconsin—Madison: Madison, WI, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mekonen, S. Coexistence between human and wildlife: The nature, causes and mitigations of human wildlife conflict around Bale Mountains National Park, Southeast Ethiopia. BMC Ecol. 2020, 20, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Vliet, N.; Gomez, J.; Quiceno-Mesa, M.P.; Escobar, J.F.; Andrade, G.; Vanegas, L.; Nasi, R. Sustainable wildlife management and legal commercial use of bushmeat in Colombia: The resource remains at the cross-road. Int. Rev. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2015, 17, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabuhoro, E.; Wright, B.A.; Powell, R.B.; Hallo, J.C.; Layton, P.A.; Munanura, I.E. Perceptions and behaviors of Indigenous populations regarding illegal use of protected area resources in East Africa’s Mountain Gorilla Landscape. Environ. Manag. 2020, 65, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindemann-Matthies, P.; Keller, D.; Li, X.; Schmid, B. Attitudes toward forest diversity and forest ecosystem services—A cross-cultural comparison between China and Switzerland. J. Plant Ecol. 2014, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venuste, N.; Olivier, H.; Valens, N. Knowledge, attitudes, and awareness of pre-service teachers on biodiversity conservation in Rwanda. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2017, 12, 643–652. [Google Scholar]

- Nyberg, E.; Castéra, J.; Mc Ewen, B.; Gericke, N.; Pierre, C. Teachers’ and Student Teachers’ Attitudes Towards Nature and the Environment—A Comparative Study Between Sweden and France. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 64, 1090–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coracero, E.E.; Facun MC, T.; Gallego RB, J.; Lingon, M.G.; Lolong, K.M.; Lugayan, M.M.; Montesines KB, G.; Sangalang, L.R.; Suniega, M.J.A. Knowledge and perspective of students towards biodiversity and its conservation and protection. Asian J. Univ. Educ. 2022, 18, 118–131. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Increasing protected areas for wild animals | 521 | 17.02 |

| Support local wildlife conservation efforts | 265 | 8.66 |

| Keeping people out of wildlife areas | 702 | 27.71 |

| Increasing the awareness about wildlife and its necessity in biodiversity | 761 | 24.86 |

| Avoid encroaching on wildlife habitats, nesting areas, and feeding grounds | 4 | 0.13 |

| Increasing coexistence between people and wildlife, giving necessary training | 67 | 2.18 |

| No attempt | 77 | 2.50 |

| No idea | 517 | 16.89 |

| Yes | No | Either Yes or No | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Freq (%) | Freq (%) | Freq (%) |

| Wildlife hunting is a task that is right to do | 354 (11.60) | 2408 (78.60) | 278 (9.10) |

| Support wildlife trade | 557 (18.20) | 2247 (73.40) | 237 (7.70) |

| Illegal wildlife hunting (wildlife-related offenses) | 1863 (60.80) | 450 (14.70) | 721 (23.5) |

| Knowledge | Chi2 | Perception | Chi2 | Practice | Chi2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Category | Low Knowledge | High Knowledge | p-Value | Bad | Good | p-Value | Bad | Good | p-Value |

| Age | 17–20 | 141 (4.60) | 191 (6.24) | 0.0001 | 93 (3.03) | 242 (7.90) | 0.0005 | 84 (2.74) | 249 (8.13) | |

| 21–30 | 649 (21.20) | 827 (27.02) | 308 (10.06) | 1469 (48.00) | 338 (11.04) | 1136 (37.09) | ||||

| 31–40 | 283 (9.24) | 409 (13.36) | 284 (9.28) | 408 (13.33) | 181 (5.91) | 511 (16.69) | ||||

| 41–50 | 186 (6.07) | 130 (4.24) | 202 (6.60) | 113 (3.69) | 137 (4.47) | 179 (5.84) | ||||

| 51–60 | 112 (3.66) | 49 (1.60) | 128 (4.18) | 33 (1.07) | 80 (2.61) | 82 (2.67) | ||||

| Above 60 | 47 (1.53) | 12 (0.39) | 49 (1.60) | 9 (0.29) | 27 (0.88) | 33 (1.07) | ||||

| Education | PhD | 5 (0.166) | 8 (0.26) | 1 (0.03) | 14 (0.45) | 15 (0.49) | 15 (0.49) | |||

| Masters | 132 (4.31) | 287 (9.37) | 48 (1.56) | 371 (12.12) | 404 (13.20) | 417 (13.62) | ||||

| Bachelor | 348 (11.36) | 479 (15.64) | 119 (3.88) | 705 (23.03) | 717 (23.42) | 826 (26.98) | ||||

| HSC | 248 (8.10) | 386 (12.61) | 145 (4.73) | 487 (15.91) | 475 (15.52) | 633 (20.68) | ||||

| SSC | 106 (3.46) | 172 (5.62) | 141 (4.60) | 139 (4.54) | 176 (5.75) | 279 (9.11) | ||||

| Up to high school | 78 (2.54) | 46 (1.50) | 93 (3.03) | 32 (1.04) | 63 (2.05) | 125 (4.08) | ||||

| Up to primary school | 45 (1.47) | 22 (0.71) | 49 (1.60) | 18 (0.58) | 26 (0.84) | 67 (2.18) | ||||

| No education | 432 (14.11) | 64 (2.09) | 435 (14.21) | 54 (1.76) | 156 (5.09) | 497 (16.24) | ||||

| Division | Barisal | 11 (0.35) | 59 (1.92) | 13 (0.42) | 57 (1.86) | 4 (0.13) | 66 (2.15) | |||

| Chattogram | 371 (12.11) | 334 (10.90) | 238 (7.80) | 468 (15.28) | 300 (9.80) | 404 (13.20) | ||||

| Dhaka | 178 (5.81) | 288 (9.41) | 119 (3.88) | 348 (11.37) | 61 (1.99) | 404 (13.20) | ||||

| Khulna | 398 (13.00) | 686 (22.41) | 493 (16.11) | 590 (19.28) | 364 (11.89) | 721 (23.56) | ||||

| Mymensingh | 55 (1.79) | 42 (1.37) | 16 (0.52) | 81 (2.64) | 10 (0.32) | 87 (2.84) | ||||

| Rajshahi | 238 (7.77) | 103 (3.36) | 122 (3.98) | 221 (7.22) | 45 (1.47) | 298 (9.73) | ||||

| Rangpur | 50 (1.63) | 44 (1.43) | 23 (0.75) | 72 (2.35) | 4 (0.13) | 91 (2.97) | ||||

| Sylhet | 128 (4.18) | 64 (2.09) | 49 (1.60) | 132 (4.32) | 65 (2.12) | 126 (4.11) | ||||

| Occupation | Banker | 7 (0.22) | 19 (0.62) | 3 (0.09) | 4 (0.13) | 4 (0.13) | 22 (0.71) | |||

| Boatman | 4 (0.13) | 1 (0.03) | 5 (0.16) | 1 (0.03) | 3 (0.09) | 2 (0.06) | ||||

| Business | 61 (1.99) | 148 (4.83) | 87 (2.84) | 123 (4.01) | 25 (0.81) | 185 (6.04) | ||||

| Car driver | 16 (0.52) | 13 (0.42) | 22 (0.71) | 7 (0.22) | 10 (0.32) | 19 (0.62) | ||||

| Engineer | 1 (0.03) | 12 (0.39) | 1 (0.03) | 12 (0.39) | 1 (0.03) | 12 (0.39) | ||||

| Farmer | 169 (5.52) | 41 (1.33) | 170 (5.55) | 36 (1.17) | 106 (3.46) | 104 (3.39) | ||||

| Fisherman | 45 (1.47) | 13 (0.42) | 47 (1.53) | 11 (0.35) | 16 (0.52) | 42 (1.37) | ||||

| Govt employe | 35 (1.14) | 55 (1.79) | 15 (0.49) | 75 (2.45) | 7 (0.22) | 83 (2.87) | ||||

| Hawker | 19 (0.62) | 1 (0.03) | 19 (0.62) | 2 (0.06) | 13 (0.42) | 8 (0.26) | ||||

| Health professionals | 31 (1.01) | 71 (2.32) | 4 (0.13) | 98 (3.20) | 2 (0.06) | 100 (3.26) | ||||

| Housewife | 275 (8.98) | 196 (6.40) | 339 (11.07) | 132 (4.31) | 281 (9.18) | 120 (3.92) | ||||

| Journalist | 1 (0.03) | 2 (0.06) | 1 (0.03) | 2 (0.06) | 1 (0.03) | 2 (0.06) | ||||

| Others | 148 (4.83) | 119 (3.88) | 115 (3.75) | 149 (4.86) | 148 (4.83) | 117 (3.82) | ||||

| Player | 1 (0.03) | 6 (0.19) | 2 (0.06) | 5 (0.16) | 3 (0.09) | 4 (0.13) | ||||

| Private employee | 38 (1.24) | 97 (3.16) | 29 (0.94) | 106 (3.46) | 11 (0.35) | 123 (4.01) | ||||

| Researcher | 3 (0.09) | 7 (0.22) | 1 (0.03) | 9 (0.29) | 1 (0.03) | 9 (0.29) | ||||

| Retired | 16 (0.52) | 11 (0.35) | 15 (0.49) | 10 (0.32) | 7 (0.22) | 20 (0.65) | ||||

| Student | 462 (15.09) | 608 (19.86) | 157 (5.13) | 911 (29.77) | 178 (5.81) | 891 (29.11) | ||||

| Teacher | 64 (2.09) | 174 (5.68) | 22 (0.71) | 217 (7.09) | 7 (0.22) | 232 (7.58) | ||||

| Unemployed | 35 (1.14) | 21 (0.68) | 19 (0.62) | 35 (1.14) | 28 (0.91) | 27 (0.88) | ||||

| Knowledge | Perception | Practice | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Category | Odds Ratio | 95% CL | Odds Ratio | CI | Odds Ratio | CI | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Age (years) | 17–20 | 2.28 | 0.23 | 22.87 | 1.24 | 0.20 | 7.71 | 2.03 | 0.34 | 12.22 |

| 21–30 | 2.30 | 0.24 | 22.60 | 2.41 | 0.40 | 14.41 | 2.16 | 0.37 | 12.73 | |

| 31–40 | 2.68 | 0.28 | 26.12 | 1.75 | 0.29 | 10.44 | 2.63 | 0.45 | 15.49 | |

| 41–50 | 1.95 | 0.20 | 19.07 | 1.34 | 0.22 | 8.05 | 1.79 | 0.30 | 10.61 | |

| 51–60 | 1.89 | 0.19 | 18.66 | 0.77 | 0.12 | 4.79 | 1.84 | 0.31 | 11.08 | |

| Above 60 | 0.73 | 0.07 | 7.63 | 0.33 | 0.05 | 2.44 | 1.18 | 0.19 | 7.53 | |

| Educational qualification | PhD | 1.85 | 0.18 | 18.68 | 1.94 | 0.19 | 20.13 | 1.76 | 0.20 | 15.18 |

| Masters | 0.74 | 0.40 | 1.34 | 1.21 | 0.72 | 2.01 | 0.89 | 0.50 | 1.60 | |

| Bachelor | 0.94 | 0.48 | 1.85 | 1.09 | 0.61 | 1.99 | 1.05 | 0.54 | 2.01 | |

| HSC | 0.45 | 0.25 | 0.80 | 0.52 | 0.33 | 0.81 | 0.51 | 0.29 | 0.89 | |

| SSC | 0.38 | 0.21 | 0.70 | 0.23 | 0.14 | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.24 | 0.78 | |

| Up to high school | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.26 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.23 | |

| Up to primary school | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.29 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.24 | |

| No education | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.06 | |

| Division | Barisal | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.43 | 0.61 | 0.28 | 1.30 | 0.21 | 0.09 | 0.50 |

| Chattogram | 0.42 | 0.18 | 1.01 | 0.57 | 0.02 | 15.23 | 0.30 | 0.02 | 4.81 | |

| Dhaka | 0.42 | 0.18 | 1.01 | 1.05 | 0.49 | 2.26 | 0.43 | 0.18 | 1.00 | |

| Khulna | 1.22 | 0.51 | 2.89 | 0.83 | 0.39 | 1.75 | 1.31 | 0.56 | 3.07 | |

| Mymensingh | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.52 | 1.29 | 0.48 | 3.45 | 0.25 | 0.10 | 0.64 | |

| Rajshahi | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.30 | 1.06 | 0.47 | 2.39 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.34 | |

| Rangpur | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.20 | 1.21 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.57 | |

| Sylhet | 0.35 | 0.13 | 0.91 | 1.98 | 0.81 | 4.83 | 0.62 | 0.25 | 1.56 | |

| Occupation | Banker | 0.24 | 0.01 | 6.45 | 0.89 | 0.09 | 9.19 | 0.52 | 0.03 | 10.36 |

| Businessman | 0.17 | 0.01 | 3.14 | 0.48 | 0.07 | 3.58 | 0.22 | 0.02 | 3.02 | |

| Car driver | 0.12 | 0.01 | 2.58 | 0.44 | 0.05 | 3.87 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 2.29 | |

| Fisherman | 0.09 | 0.00 | 1.71 | 0.41 | 0.05 | 3.12 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 3.28 | |

| Government employee | 0.09 | 0.00 | 1.75 | 0.46 | 0.05 | 3.81 | 0.26 | 0.02 | 3.63 | |

| Hawker | 0.16 | 0.01 | 3.17 | 0.84 | 0.11 | 6.52 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.48 | |

| Health professionals | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.56 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 2.44 | 0.68 | 0.05 | 9.75 | |

| Housewife | 0.62 | 0.02 | 12.30 | 3.01 | 0.31 | 34.04 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 4.68 | |

| Private employee | 0.15 | 0.01 | 2.72 | 0.53 | 0.07 | 3.89 | 0.41 | 0.03 | 5.88 | |

| Researcher | 0.24 | 0.01 | 9.61 | 0.94 | 0.07 | 12.56 | 0.54 | 0.02 | 15.17 | |

| Retired | 0.27 | 0.01 | 5.23 | 0.84 | 0.11 | 6.33 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 2.87 | |

| Student | 0.46 | 0.01 | 17.13 | 0.65 | 0.08 | 5.38 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 3.02 | |

| Teacher | 0.14 | 0.01 | 3.25 | 0.77 | 0.07 | 8.06 | 0.19 | 0.01 | 2.67 | |

| Unemployed | 0.16 | 0.01 | 3.06 | 0.98 | 0.13 | 7.26 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 2.90 | |

| Others | 0.09 | 0.00 | 1.64 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.93 | 0.26 | 0.02 | 3.52 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shawon, R.A.R.; Rahman, M.M.; Dandi, S.O.; Agbayiza, B.; Iqbal, M.M.; Sakyi, M.E.; Moribe, J. Knowledge, Perception, and Practices of Wildlife Conservation and Biodiversity Management in Bangladesh. Animals 2025, 15, 296. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15030296

Shawon RAR, Rahman MM, Dandi SO, Agbayiza B, Iqbal MM, Sakyi ME, Moribe J. Knowledge, Perception, and Practices of Wildlife Conservation and Biodiversity Management in Bangladesh. Animals. 2025; 15(3):296. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15030296

Chicago/Turabian StyleShawon, Raf Ana Rabbi, Md. Matiur Rahman, Samuel Opoku Dandi, Ben Agbayiza, Md Mehedi Iqbal, Michael Essien Sakyi, and Junji Moribe. 2025. "Knowledge, Perception, and Practices of Wildlife Conservation and Biodiversity Management in Bangladesh" Animals 15, no. 3: 296. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15030296

APA StyleShawon, R. A. R., Rahman, M. M., Dandi, S. O., Agbayiza, B., Iqbal, M. M., Sakyi, M. E., & Moribe, J. (2025). Knowledge, Perception, and Practices of Wildlife Conservation and Biodiversity Management in Bangladesh. Animals, 15(3), 296. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15030296