Transcriptomic and Physiological Responses Reveal a Time-Associated Multi-Organ Injury Pattern in European Perch (Perca fluviatilis) Under Acute Alkaline Stress

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Animals and Acclimation

2.2. Alkaline Stress Experimental Design

2.3. Sample Collection and Processing

2.4. Histological and Biochemical Analysis

2.5. RNA Extraction, Transcriptome Sequencing, and Bioinformatics Analysis

2.6. cDNA Synthesis and qRT-PCR Validation

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

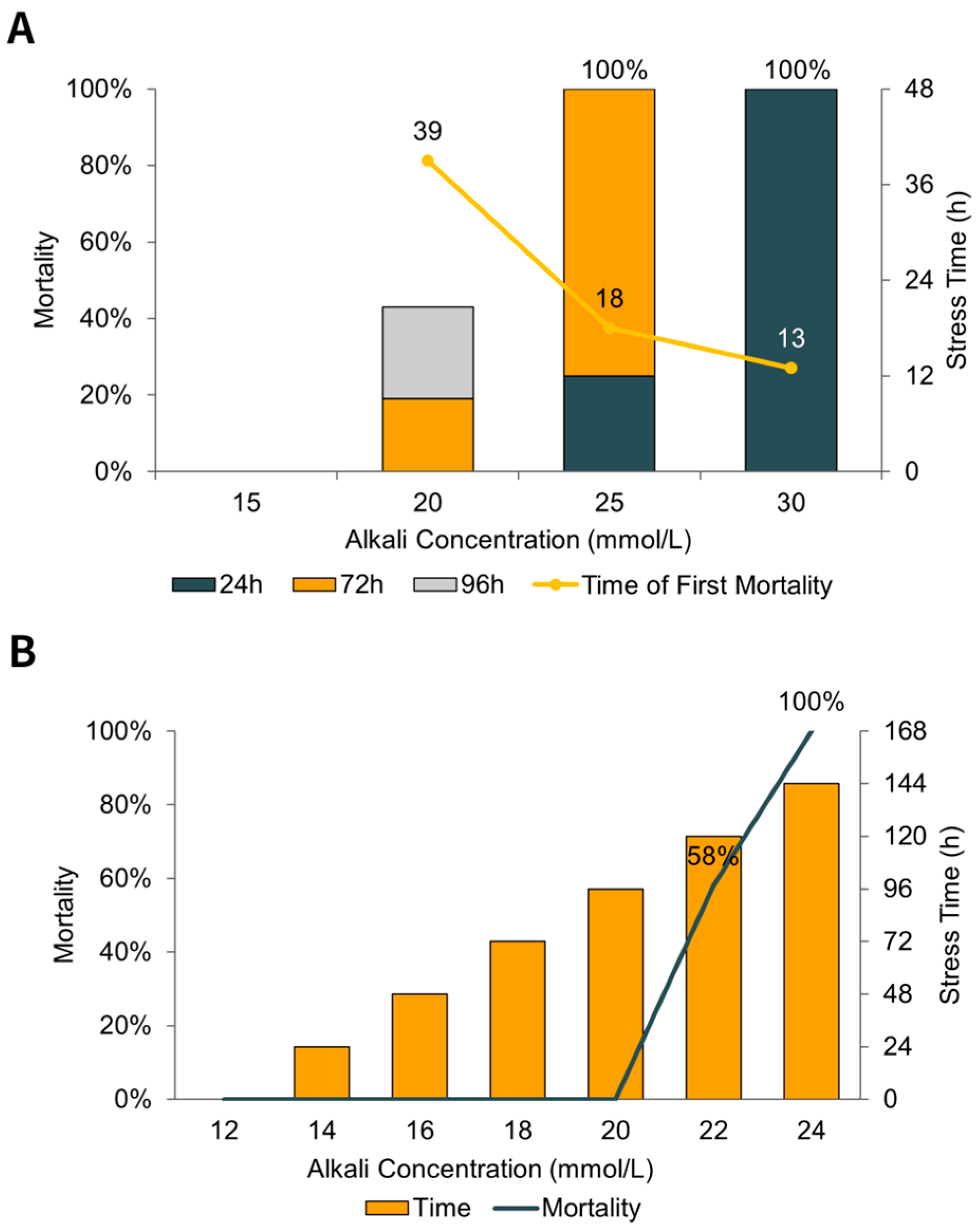

3.1. Alkaline Stress Experiment

3.2. Acute Alkaline Stress Induces Rapid and Progressive Pathological Damage in Gills and Liver

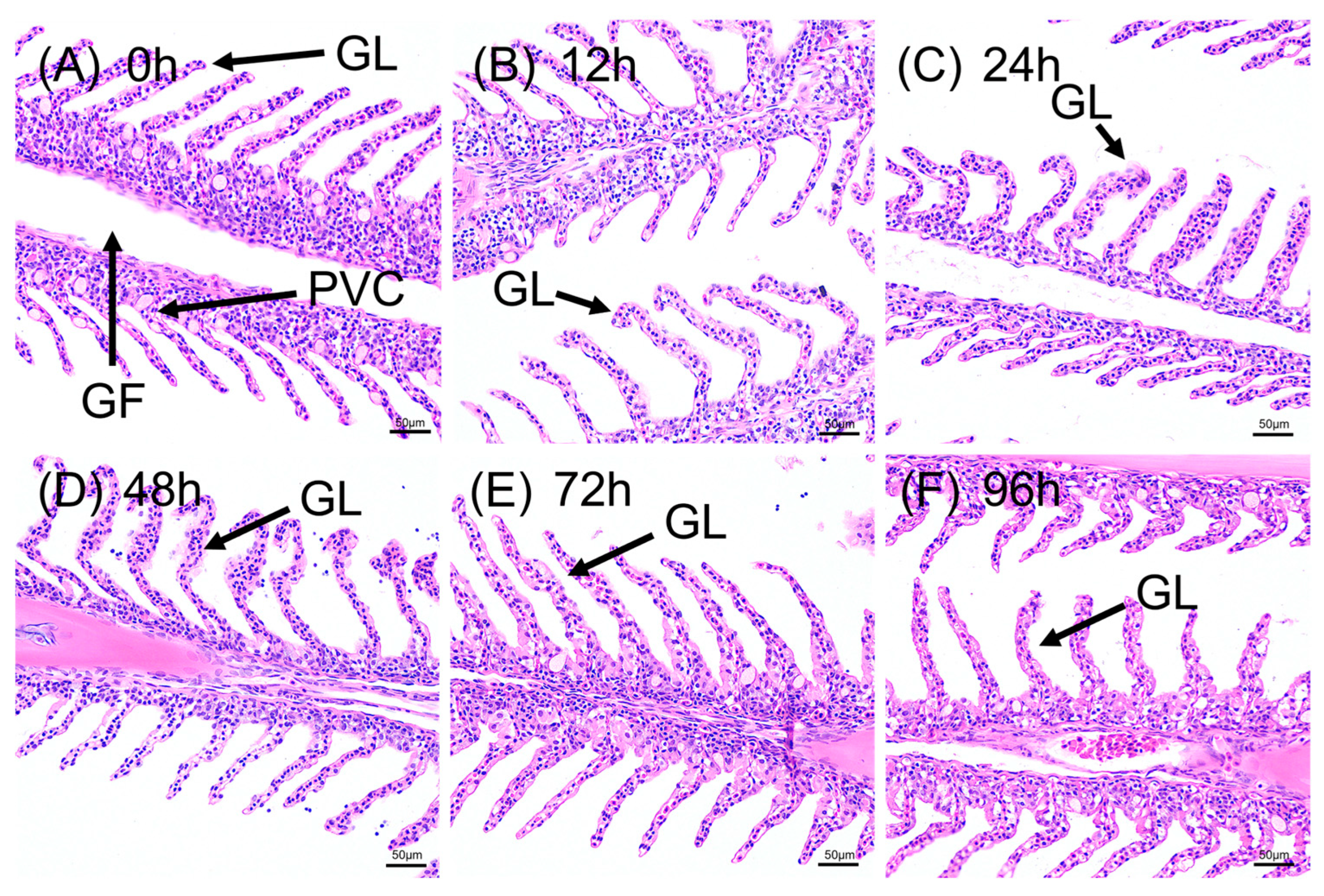

3.2.1. Structural Degeneration of Gill Tissue

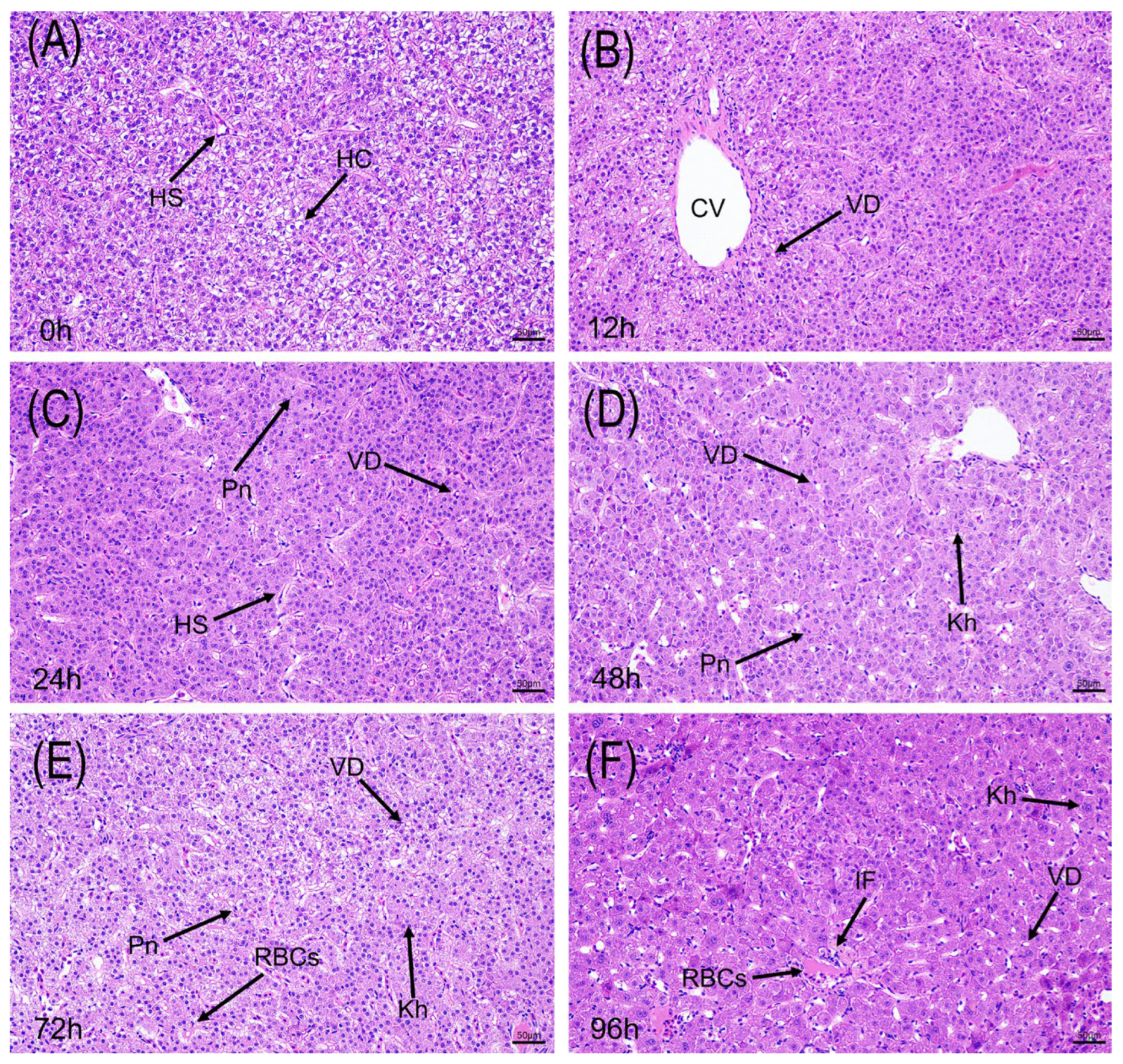

3.2.2. Pathological Changes in Liver Tissue

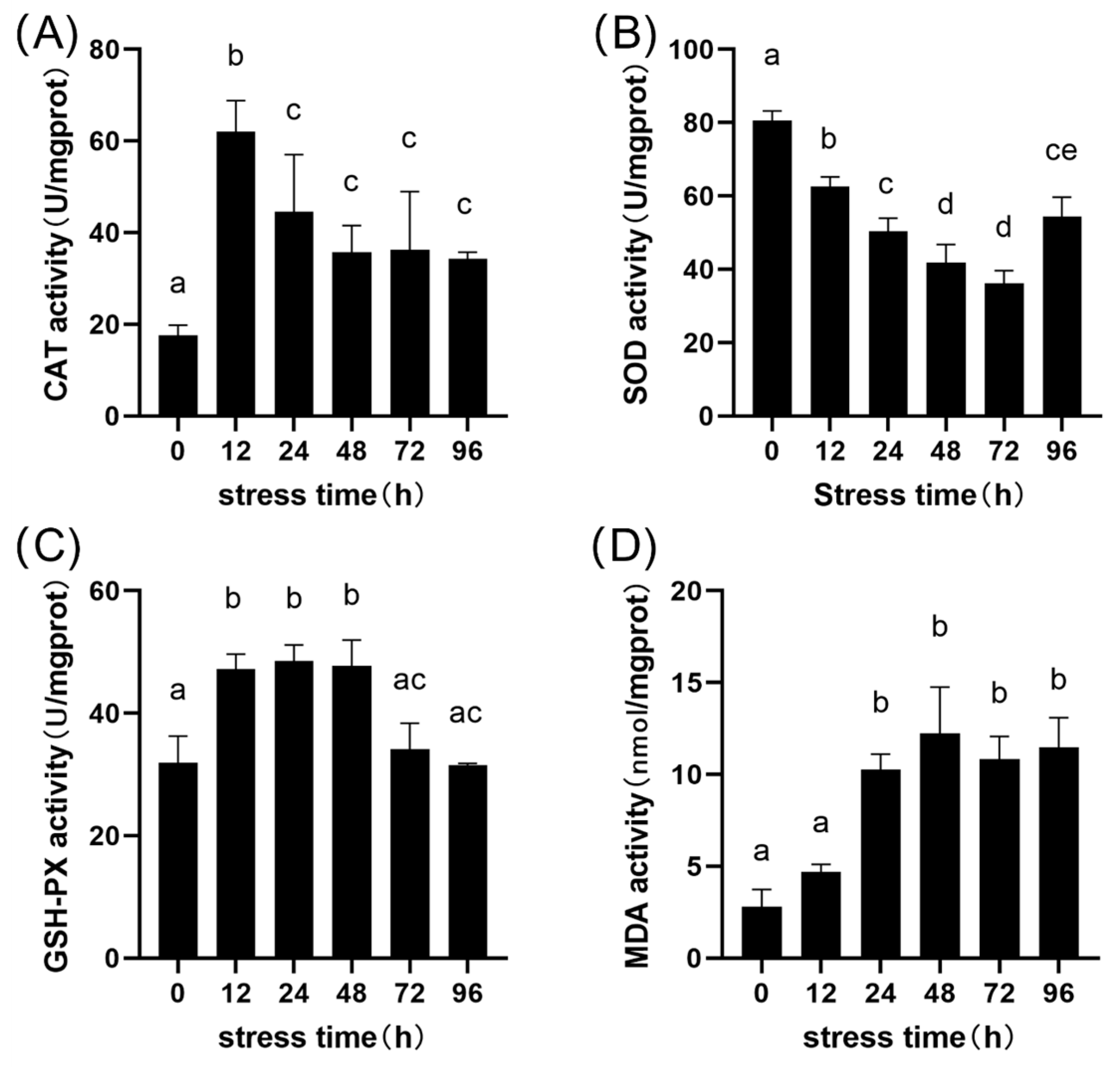

3.3. Hepatic Oxidative Stress Response

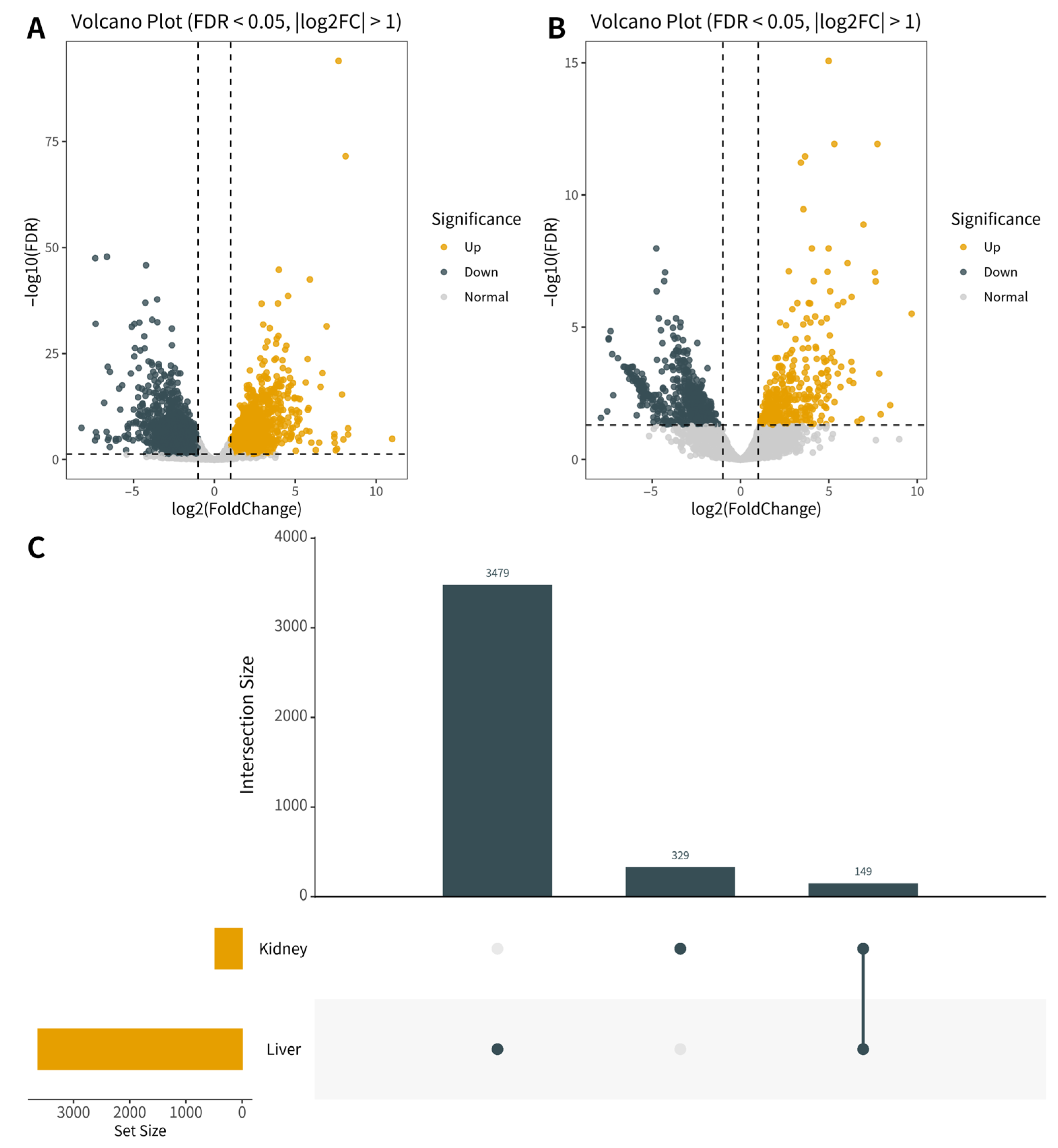

3.4. Transcriptome Sequencing Reveals Large-Scale Gene Reprogramming in Liver and Kidney

3.5. Functional Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

3.6. Key Differentially Expressed Genes

3.7. Validation of RNA-Seq Data by qRT-PCR

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| acod1 | aconitate decarboxylase 1 |

| aldh18a1 | aldehyde dehydrogenase 18 family member A1 |

| ampd2b | adenosine monophosphate deaminase 2b |

| angptl3 | angiopoietin like 3 |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| asb10 | ankyrin repeat and SOCS box containing 10 |

| atp6v1ab | ATPase H+ Transporting V1 Subunit A, isoform b |

| BCA | Bicinchoninic acid assay |

| BH | Benjamini–Hochberg procedure |

| c9 | complement C9 |

| CAT | Catalase |

| cDNA | complementary DNA |

| CV | central vein |

| DEGs | Differentially Expressed Genes |

| dgat2 | Diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 2 |

| egln3 | egl-9 family hypoxia inducible factor 3 |

| fabp10a | fatty acid binding protein 10a, liver basic |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| FPKM | Fragments Per Kilobase per Million bases |

| Gb | Gigabases |

| GC | Guanine-Cytosine content |

| GF | Gill Filaments |

| GL | Gill Lamellae |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| GSH-Px | Glutathione Peroxidase |

| H&E | Hematoxylin-Eosin |

| HC | hepatocytes |

| HIF-1 | Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1 |

| higd1a | HIG1 hypoxia inducible domain family member 1A |

| hsp90aa1.2 | Heat shock protein 90 alpha family class A member 1.2 |

| HS | hepatic sinusoids |

| ldha | Lactate dehydrogenase A |

| IF | inflammatory cell infiltration |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| Kh | karyorrhexis |

| klhl38b | kelch-like family member 38b |

| LC50 | Median lethal concentration |

| MAS | marker-assisted selection |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| MS-222 | Tricaine methanesulfonate |

| myl13 | myosin, light chain 13 |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| PCO2 | Partial pressure of Carbon Dioxide |

| pfkfb3 | 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3 |

| Pn | pyknosis |

| PQC | protein quality control |

| prkcg | protein kinase C gamma |

| prlra | prolactin receptor a |

| PVC | pavement cells |

| qRT-PCR | quantitative real-time PCR |

| rbpjl | recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin kappa J region like |

| RNA-Seq | RNA Sequencing |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RSEM | RNA-Seq by Expectation-Maximization |

| SD | standard deviation |

| slc7a11 | solute carrier family 7 member 11 |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| SRA | Sequence Read Archive |

| stard5 | StAR related lipid transfer domain containing 5 |

| tcirg1b | T-cell immune regulator 1, member b |

| ucp1 | uncoupling protein 1 |

| uox | urate oxidase |

| VD | vacuolar degeneration |

References

- Ye, W.; Wang, W.; Hua, J.; Xu, D.; Qiang, J. Physiological and Transcriptome Analyses Offer Insights into Revealing the Mechanisms of Red Tilapia (Oreochromis spp.) in Response to Carbonate Alkalinity Stress. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Y.; Liu, H.; Yuan, H.; Du, X.; Huang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y. Comparative Mechanisms of Acute High-Alkalinity Stress on the Normal and Hybrid Populations of Pacific White Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1559292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, Á.; Homoki, D.Z.; Bársony, P.; Kertész, A.; Remenyik, J.; Pesti-Asbóth, G.; Fehér, M. The Effects of Contrast between Dark- and Light-Coloured Tanks on the Growth Performance and Antioxidant Parameters of Juvenile European Perch (Perca fluviatilis). Water 2022, 14, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, Á.; Kovács, L.; Homoki, D.; Minya, D.; Fehér, M. Examining the Production Parameters of European Perch (Perca fluviatilis) Juveniles under Different Lighting Conditions. Acta Agrar. Debreceniensis 2021, 1, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Guo, K.; Luo, L.; Zhang, R.; Xu, W.; Song, Y.; Zhao, Z. Fattening in Saline and Alkaline Water Improves the Color, Nutritional and Taste Quality of Adult Chinese Mitten Crab Eriocheir Sinensis. Foods 2022, 11, 2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.H.; Piermarini, P.M.; Choe, K.P. The Multifunctional Fish Gill: Dominant Site of Gas Exchange, Osmoregulation, Acid-Base Regulation, and Excretion of Nitrogenous Waste. Physiol. Rev. 2005, 85, 97–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, C.M. Toxic Responses of the Gill. In Target Organ Toxicity in Marine and Freshwater Teleosts; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Heisler, N. 6 Acid-Base Regulation in Fishes*. In Fish Physiology; Gills; Hoar, W.S., Randall, D.J., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984; Volume 10, pp. 315–401. [Google Scholar]

- Ip, A.Y.K.; Chew, S.F. Ammonia Production, Excretion, Toxicity, and Defense in Fish: A Review. Front. Physiol. 2010, 1, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lushchak, V.I. Environmentally Induced Oxidative Stress in Aquatic Animals. Aquat. Toxicol. 2011, 101, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. Oxidative Stress: A Concept in Redox Biology and Medicine. Redox Biol. 2015, 4, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valko, M.; Leibfritz, D.; Moncol, J.; Cronin, M.T.D.; Mazur, M.; Telser, J. Free Radicals and Antioxidants in Normal Physiological Functions and Human Disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007, 39, 44–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ighodaro, O.M.; Akinloye, O.A. First Line Defence Antioxidants-Superoxide Dismutase (SOD), Catalase (CAT) and Glutathione Peroxidase (GPX): Their Fundamental Role in the Entire Antioxidant Defence Grid. Alex. J. Med. 2018, 54, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gerstein, M.; Snyder, M. RNA-Seq: A Revolutionary Tool for Transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Wang, W.; Li, J.; Feng, W.; Kamunga, E.M.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, Y. Physiological and Molecular Responses of Juvenile Silver Crucian Carp (Carassius gibelio) to Long-Term High Alkaline Stress: Growth Performance, Histopathology, and Transcriptomic Analysis. Aquac. Rep. 2024, 39, 102393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zheng, J.; Xu, Y.; Li, F.; Liu, S.; Jiang, W.; Chi, M.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, H. Changes in the Physiological Indicators and Gene Expression for Grass Carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) in Response to Alkaline Stress. Aquac. Int. 2025, 33, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomczynski, P.; Sacchi, N. Single-Step Method of RNA Isolation by Acid Guanidinium Thiocyanate-Phenol-Chloroform Extraction. Anal. Biochem. 1987, 162, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. Fastp: An Ultra-Fast All-in-One FASTQ Preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A Fast Spliced Aligner with Low Memory Requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhl, H.; Euclide, P.T.; Klopp, C.; Cabau, C.; Zahm, M.; Lopez-Roques, C.; Iampietro, C.; Kuchly, C.; Donnadieu, C.; Feron, R.; et al. Multi-Genome Comparisons Reveal Gain-and-Loss Evolution of Anti-Mullerian Hormone Receptor Type 2 as a Candidate Master Sex-Determining Gene in Percidae. BMC Biol. 2024, 22, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Dewey, C.N. RSEM: Accurate Transcript Quantification from RNA-Seq Data with or without a Reference Genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, A.; Williams, B.A.; McCue, K.; Schaeffer, L.; Wold, B. Mapping and Quantifying Mammalian Transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat. Methods 2008, 5, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Gene Ontology Consortium. The Gene Ontology Resource: Enriching a GOld Mine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D325–D334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Abudu, A.; Zhu, K.; Han, T.; Duan, C.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Shi, G.; Zhu, C.; Li, G.; et al. Acute Alkalinity Stress Induces Functional Damage and Alters Immune Metabolic Pathways in the Gill Tissue of Spotted Scat (Scatophagus argus). Aquaculture 2025, 599, 742186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, J.; Tao, Y.; Lu, S.; Li, Y.; Dong, Y.; Jiang, B.; Xi, B.; Qiang, J. Integration of Transcriptome, Histopathology, and Physiological Indicators Reveals Regulatory Mechanisms of Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) in Response to Carbonate Alkalinity Stress. Aquaculture 2025, 596, 741883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, D.d.S.; Moraes, B.; Becker, A.G.; Crestani, M.; Spanevello, R.; Loro, V.L.; Baldisserotto, B. Ammonia and pH Effects on Some Metabolic Parameters and Gill Histology of Silver Catfish, Rhamdia Quelen (Heptapteridae). Aquaculture 2008, 277, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, D.J.; Tsui, T.K.N. Ammonia Toxicity in Fish. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2002, 45, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Liu, Y.; Wei, X.; Geng, C.; Liu, W.; Han, L.; Yuan, F.; Wang, P.; Sun, Y. Effects of Saline-Alkaline Stress on Metabolome, Biochemical Parameters, and Histopathology in the Kidney of Crucian Carp (Carassius auratus). Metabolites 2023, 13, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayala, A.; Muñoz, M.F.; Argüelles, S. Lipid Peroxidation: Production, Metabolism, and Signaling Mechanisms of Malondialdehyde and 4-Hydroxy-2-Nonenal. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 360438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Ge, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, M.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Li, J. Metabolomic Responses Based on Transcriptome of the Hepatopancreas in Exopalaemon carinicauda under Carbonate Alkalinity Stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 268, 115723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.; Geng, L.; Wei, H.J.; Liu, T.; Che, X.; Li, W.; Liu, Y.; Shi, X.D.; Li, J.; Teng, X.; et al. Analysis Revealed the Molecular Mechanism of Oxidative Stress-Autophagy-Induced Liver Injury Caused by High Alkalinity: Integrated Whole Hepatic Transcriptome and Metabolome. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1431224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanoa, B.S.; Cogliati, T.; Satish, A.G.; Bruford, E.A.; Friedman, J.S. Update on the Kelch-like (KLHL) Gene Family. Hum. Genom. 2013, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anasa, V.V.; Ravanan, P.; Talwar, P. Multifaceted Roles of ASB Proteins and Its Pathological Significance. Front. Biol. 2018, 13, 376–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardley, H.C.; Robinson, P.A. E3 Ubiquitin Ligases. Essays Biochem. 2005, 41, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laloum, T.; Martín, G.; Duque, P. Alternative Splicing Control of Abiotic Stress Responses. Trends Plant Sci. 2018, 23, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushik, S.; Cuervo, A.M. The Coming of Age of Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, I.D.; Verlander, J.W. Ammonia Transporters and Their Role in Acid-Base Balance. Physiol. Rev. 2017, 97, 465–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewerenz, J.; Hewett, S.J.; Huang, Y.; Lambros, M.; Gout, P.W.; Kalivas, P.W.; Massie, A.; Smolders, I.; Methner, A.; Pergande, M.; et al. The Cystine/Glutamate Antiporter System Xc− in Health and Disease: From Molecular Mechanisms to Novel Therapeutic Opportunities. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 522–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherghina, M.-E.; Peride, I.; Tiglis, M.; Neagu, T.P.; Niculae, A.; Checherita, I.A. Uric Acid and Oxidative Stress—Relationship with Cardiovascular, Metabolic, and Renal Impairment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, G.-H.; Takeda, K. Role and Regulation of Prolyl Hydroxylase Domain Proteins. Cell Death Differ. 2008, 15, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-Y.; Chen, M.; Mu, W.-J.; Luo, H.-Y.; Guo, L. The Functional Role of Higd1a in Mitochondrial Homeostasis and in Multiple Disease Processes. Genes Dis. 2023, 10, 1833–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, T.; McCormick, S.D. Prolactin and Growth Hormone in Fish Osmoregulation. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2006, 147, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Zhang, L.; Natarajan, S.K.; Becker, D.F. Proline Mechanisms of Stress Survival. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 19, 998–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massolini, G.; Calleri, E. Survey of Binding Properties of Fatty Acid-Binding Proteins: Chromatographic Methods. J. Chromatogr. B 2003, 797, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikka, A.; Jauhiainen, M. The Role of ANGPTL3 in Controlling Lipoprotein Metabolism. Endocrine 2016, 52, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lettieri-Barbato, D. Redox Control of Non-Shivering Thermogenesis. Mol. Metab. 2019, 25, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rus, H.; Cudrici, C.; Niculescu, F. The Role of the Complement System in Innate Immunity. Immunol. Res. 2005, 33, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Control Group | Alkaline Stress Group | Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.8 ± 0.2 | 9.4 ± 0.3 | YSI ProPlus Meter |

| Total Alkalinity (mmol/L) | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 20.0 ± 0.2 | Acid–Base Titration |

| Total Hardness (mg/L CaCO3) | 180.5 ± 4.2 | 168.7 ± 6.5 | EDTA Titration |

| Dissolved Oxygen (mg/L) | 7.6 ± 0.4 | 7.4 ± 0.6 | YSI ProPlus Meter |

| TAN (mg/L) | <0.02 | <0.02 | Nessler’s Colorimetry |

| Ca2+ (mg/L) | 54.1 ± 2.8 | 49.5 ± 3.2 | EDTA Titration |

| Mg2+ (mg/L) | 10.9 ± 1.5 | 10.8 ± 1.8 | Calculated |

| Na+ (mg/L) | 32.5 ± 3.4 | 482.2 ± 10.6 | Flame Photometry |

| K+ (mg/L) | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | Flame Photometry |

| Tissue | Gene Symbol | FDR | log2FC | Regulated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kidney | acod1 | 0.000433265 | 6.33354 | up |

| prlra | 7.10 × 10−7 | 6.290565 | up | |

| myl13 | 0.000314724 | 5.697281 | up | |

| klhl38b | 0.000570015 | 5.502371 | up | |

| asb10 | 0.000205197 | 5.316526 | up | |

| slc7a11 | 1.18 × 10−12 | 5.309597 | up | |

| uox | 1.41 × 10−5 | −7.35524 | down | |

| fabp10a | 0.000147944 | −6.94263 | down | |

| ucp1 | 0.00089816 | −6.29334 | down | |

| c9 | 0.001419869 | −5.85674 | down | |

| Liver | stard5 | 4.39 × 10−8 | 8.261538 | up |

| aldh18a1 | 1.37 × 10−6 | 8.261132 | up | |

| higd1a | 3.84 × 10−32 | 6.940015 | up | |

| egln3 | 0.000101412 | 6.475258 | up | |

| slc7a11 | 3.38 × 10−43 | 5.905609 | up | |

| angptl3 | 1.01 × 10−32 | −7.33362 | down | |

| ampd2b | 2.34 × 10−5 | −6.57406 | down | |

| rbpjl | 6.77 × 10−6 | −6.53325 | down | |

| uox | 1.62 × 10−5 | −5.90873 | down | |

| prkcg | 1.70 × 10−12 | −5.81153 | down |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, G.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Gao, P.; Hu, J.; Sun, P.; Peng, F.; Chen, P.; Xu, J. Transcriptomic and Physiological Responses Reveal a Time-Associated Multi-Organ Injury Pattern in European Perch (Perca fluviatilis) Under Acute Alkaline Stress. Animals 2025, 15, 3621. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243621

Chen G, Liu Y, Li X, Gao P, Hu J, Sun P, Peng F, Chen P, Xu J. Transcriptomic and Physiological Responses Reveal a Time-Associated Multi-Organ Injury Pattern in European Perch (Perca fluviatilis) Under Acute Alkaline Stress. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3621. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243621

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Geng, Yi Liu, Xiaodong Li, Pan Gao, Jianyong Hu, Pengfei Sun, Fangyuan Peng, Peng Chen, and Jin Xu. 2025. "Transcriptomic and Physiological Responses Reveal a Time-Associated Multi-Organ Injury Pattern in European Perch (Perca fluviatilis) Under Acute Alkaline Stress" Animals 15, no. 24: 3621. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243621

APA StyleChen, G., Liu, Y., Li, X., Gao, P., Hu, J., Sun, P., Peng, F., Chen, P., & Xu, J. (2025). Transcriptomic and Physiological Responses Reveal a Time-Associated Multi-Organ Injury Pattern in European Perch (Perca fluviatilis) Under Acute Alkaline Stress. Animals, 15(24), 3621. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243621