Breeding and Disease Resistance Evaluation of a New Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) Strain Resistant to Largemouth Bass Virus (LMBV)

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fish and Virus

2.2. Generational Breeding of Largemouth Bass for Disease Resistance

2.3. Comparison of Survival Rates Across the Three Breeding Generations After LMBV Infection

2.4. Viral Load Dynamics

2.5. Expression of Immune-Related Genes

2.5.1. Challenge Experiment and Sample Collection

2.5.2. RNA Extraction and Tr2anscription

2.5.3. Expression of the Immune-Related Genes

2.6. Antioxidant Capacity Assessment

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

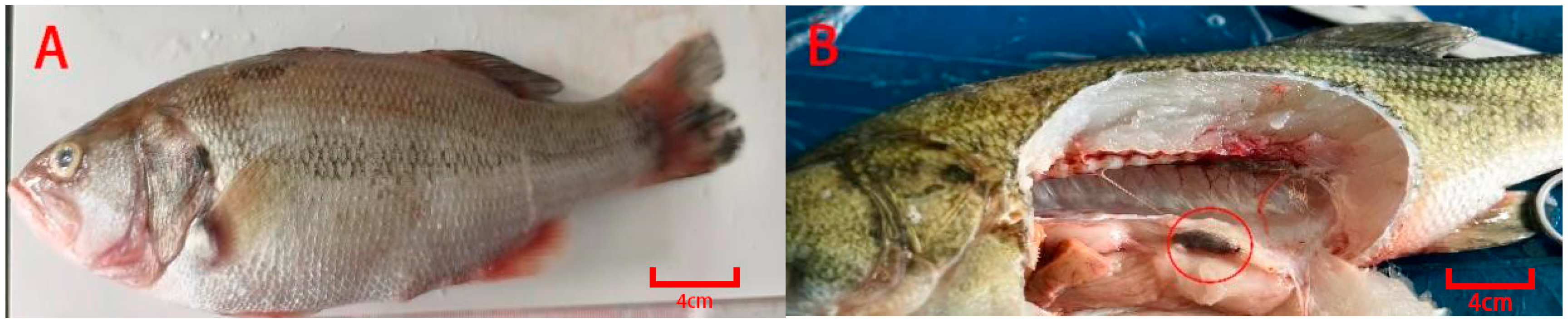

3.1. Breeding of Candidate Populations Resistant to LMBV

3.2. Comparative Experiment on Viral Resistance

3.3. Immune-Related Gene Expression Analysis

3.4. Antioxidant Capacity Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Y.; Gui, B.; Jia, Z.; Li, Y.; Liao, L.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Huang, R. Artificial Infection Pathway of Largemouth Bass LMBV and Identification of Resistant and Susceptible Individuals. Aquaculture 2024, 582, 740527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, B.; Yu, R.; Xu, W.; Liu, X.; Su, J.; Yuan, G. Hepcidin Contributes to Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) against Bacterial Infections. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 266, 131144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, W.; Shao, W.; He, Z.; Lu, Y.; Xin, Y.; Shen, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, X. Viral Metagenome Analysis Uncovers Hidden RNA Virome Diversity in Juvenile Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides). Aquaculture 2025, 595, 741571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grizzle, J.; Altinok, I.; Fraser, W.; Francis-Floyd, R. First Isolation of Largemouth Bass Virus. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2002, 50, 233–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.; Li, S.; Xie, J.; Bai, J.; Chen, K.; Ma, D.; Jiang, X.; Lao, H.; Yu, L. Characterization of a Ranavirus Isolated from Cultured Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) in China. Aquaculture 2011, 312, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Geng, Y.; Qin, Z.; Wang, K.; Ouyang, P.; Chen, D.; Huang, X.; Zuo, Z.; He, C.; Guo, H.; et al. A New Ranavirus of the Santee-Cooper Group Invades Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) Culture in Southwest China. Aquaculture 2020, 526, 735363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Lin, Q.; Liang, H.; Liu, L.; Huang, Z.; Li, N.; Su, J. The Biological Features and Genetic Diversity of Novel Fish Rhabdovirus Isolates in China. Arch. Virol. 2017, 162, 2829–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhong, Y.; Luo, M.; Zheng, G.; Huang, J.; Wang, G.; Geng, Y.; Qian, X. Largemouth Bass Ranavirus: Current Status and Research Progression. Aquac. Rep. 2023, 32, 101706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonthai, T.; Loch, T.P.; Yamashita, C.J.; Smith, G.D.; Winters, A.D.; Kiupel, M.; Brenden, T.O.; Faisal, M. Laboratory Investigation into the Role of Largemouth Bass Virus (Ranavirus, Iridoviridae) in Smallmouth Bass Mortality Events in Pennsylvania Rivers. BMC Vet. Res. 2018, 14, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Liu, D.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; He, H.; He, B.; Zhu, L.; Chu, P. Pathogenicity Characterization, Immune Response Mechanisms, and Antiviral Strategies Analysis Underlying a LMBV Strain in Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides). Aquacult. Rep. 2024, 36, 102133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Lai, F.; Yang, J.; Qin, Q.; Huang, Y.; Huang, X. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Host Immune Response upon LMBV Infection in Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides). Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2023, 137, 108753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plumb, J.A.; Zilberg, D. Survival of Largemouth Bass Iridovirus in Frozen Fish. J. Aquat. Anim. Health 1999, 11, 94–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Dong, J.; Li, W.; Tian, Y.; Hu, J.; Ye, X. Response to Four Generations of Selection for Growth Performance Traits in Mandarin Fish (Siniperca chuatsi). Aquaculture 2022, 548, 737590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjedrem, T. The First Family-based Breeding Program in Aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 2010, 2, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Hayes, B.J.; Guthridge, K.; Ab Rahim, E.S.; Ingram, B.A. Use of a Microsatellite-based Pedigree in Estimation of Heritabilities for Economic Traits in Australian Blue Mussel, Mytilus galloprovincialis. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 2011, 128, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, G.H.; Wang, L.; Sun, F.; Yang, Z.T.; Wong, J.; Wen, Y.F.; Pang, H.Y.; Lee, M.; Yeo, S.T.; Liang, B.; et al. Improving Growth, Omega-3 Contents, and Disease Resistance of Asian Seabass: Status of a 20-Year Family-Based Breeding Program. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2024, 34, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Luo, X.; Zuo, S.; Fu, X.; Lin, Q.; Niu, Y.; Liang, H.; Ma, B.; Li, N. Genome-Wide Association Study of Resistance to Largemouth Bass Ranavirus (LMBV) in Micropterus salmoides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Lin, Q.; Liu, L.; Liang, H.; Huang, Z.; Li, N. The Pathogenicity and Biological Features of Santee-Cooper Ranaviruses Isolated from Chinese Perch and Snakehead Fish. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 112, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Li, N.; Lai, Y.; Luo, X.; Wang, Y.; Shi, C.; Huang, Z.; Wu, S.; Su, J. A Novel Fish Cell Line Derived from the Brain of Chinese Perch Development and Characterization. J. Fish Biol. 2015, 86, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galkanda-Arachchige, H.S.C.; Davis, R.P.; Nazeer, S.; Ibarra-Castro, L.; Davis, D.A. Effect of Salinity on Growth, Survival, and Serum Osmolality of Red Snapper, Lutjanus campechanus. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 47, 1687–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, M.; Zhang, X.; Shi, Q.; Xu, Z. Fish Genomics and Its Application in Disease-Resistance Breeding. Rev. Aquac. 2025, 17, e12973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuji, K.; Hasegawa, O.; Honda, K.; Kumasaka, K.; Sakamoto, T.; Okamoto, N. Marker-Assisted Breeding of a Lymphocystis Disease-Resistant Japanese Flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). Aquaculture 2007, 272, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suebsong, W.; Poompuang, S.; Srisapoome, P.; Koonawootrittriron, S.; Luengnaruemitchai, A.; Johansen, H.; Rye, M. Selection Response for Streptococcus Agalactiae Resistance in Nile Tilapia Oreochromis Niloticus. J. Fish Dis. 2019, 42, 1553–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Fu, Y.; Wu, H.; Chen, X.; Liu, S.; Feng, H. MAVS of Triploid Hybrid of Red Crucian Carp and Allotetraploid Possesses the Improved Antiviral Activity Compared with the Counterparts of Its Parents. Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2019, 89, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrier, E.R.; Dorson, M.; Mauger, S.; Torhy, C.; Ciobotaru, C.; Hervet, C.; Dechamp, N.; Genet, C.; Boudinot, P.; Quillet, E. Resistance to a Rhabdovirus (VHSV) in Rainbow Trout: Identification of a Major QTL Related to Innate Mechanisms. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhou, T.; Bai, H.; Ke, Q.; Li, B.; Bai, M.; Zhou, Z.; Pu, F.; Zheng, W.; Xu, P. Genome-Wide Association Analysis Reveals the Genetic Architecture of Parasite (Cryptocaryon irritans) Resistance in Large Yellow Croaker (Larimichthys crocea). Mar. Biotechnol. 2021, 23, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couper, K.N.; Blount, D.G.; Riley, E.M. IL-10: The Master Regulator of Immunity to Infection. J. Immunol. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Immunol. 2008, 180, 5771–5777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.W.; de Waal Malefyt, R.; Coffman, R.L.; O’Garra, A. Interleukin-10 and the Interleukin-10 Receptor. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2001, 19, 683–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutz, S.; Ouyang, W.; Crellin, N.K.; Valdez, P.A.; Hymowitz, S.G. Regulation and Functions of the IL-10 Family of Cytokines in Inflammation and Disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 29, 71–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, F.; Olaf, M. Interrelation of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Neurodegenerative Disease: Role of TNF. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015, 610813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Yan, K.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; He, Y.; Wang, E.; Wang, G. Dietary Sanguinarine Enhances Disease Resistance to Aeromonas Dhakensis in Largemouth (Micropterus Salmoides). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2025, 165, 110577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Huo, X.; Tian, Q.; Wang, P.; Zhao, F.; Yang, C.; Su, J. The Oral Antigen-Adjuvant Fusion Vaccine P-MCP-FlaC Provides Effective Protective Effect against Largemouth Bass Ranavirus Infection. Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2023, 142, 109179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wessel, Ø.; Haugland, Ø.; Rode, M.; Fredriksen, B.N.; Dahle, M.K.; Rimstad, E. Inactivated Piscine orthoreovirus Vaccine Protects against Heart and Skeletal Muscle Inflammation in Atlantic Salmon. J. Fish Dis. 2018, 41, 1411–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamek, M.; Matras, M.; Dawson, A.; Piackova, V.; Gela, D.; Kocour, M.; Adamek, J.; Kaminski, R.; Rakus, K.; Bergmann, S.M.; et al. Type I Interferon Responses of Common Carp Strains with Different Levels of Resistance to Koi Herpesvirus Disease during Infection with CyHV-3 or SVCV. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 87, 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Ge, X.; Lin, H.; Niu, J. Effect of Dietary Carbohydrate on Non-Specific Immune Response, Hepatic Antioxidative Abilities and Disease Resistance of Juvenile Golden Pompano (Trachinotus ovatus). Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2014, 41, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraternale, A.; Paoletti, M.F.; Casabianca, A.; Nencioni, L.; Garaci, E.; Palamara, A.T.; Magnani, M. GSH and Analogs in Antiviral Therapy. Mol. Asp. Med. 2009, 30, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name | Sequences (5′-3) | Accession Numbers | Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| GADD45b-F | CTTTCTGCTGCGACAACGAC | XM_038699817.1 | 138 bp |

| GADD45b-R | GAGGGTTCGTGACCAGGATG | ||

| FOXO3-F | ACAAGTACACCAAGTCCGCC | XM_038727152.1 | 196 bp |

| FOXO3-R | CTGGCGTTGGAATTAGTGCG | ||

| IL-10-F | CTAGACCAGAGCGTCGAGGA | XM_038696252.1 | 103 bp |

| IL-10-R | CCAAGGCTGTTGGCAGAATC | ||

| TNF-α-F | ATCTGCTGTGAATGCCGTGA | OK493793.1 | 203 bp |

| TNF-α-R | CGTCAGCCTGGATAGACGAC | ||

| IFN-γ-F | TGCAGGCTCTCAAACACATC | XM_038707474.1 | 105 bp |

| IFN-γ-R | TGTTTTCGGTCAGTGTGCTC | ||

| 18s-F | TGACGGAAGGGCACCACCAG | XR_005440960.1 | 130 bp |

| 18s-R | GCACCACCACCCACAGAATCG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, W.; Li, P.; Luo, X.; Li, N.; Lin, Q.; Liang, H.; Niu, Y.; Ma, B.; Xiao, W.; Fu, X. Breeding and Disease Resistance Evaluation of a New Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) Strain Resistant to Largemouth Bass Virus (LMBV). Animals 2025, 15, 3510. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243510

Li W, Li P, Luo X, Li N, Lin Q, Liang H, Niu Y, Ma B, Xiao W, Fu X. Breeding and Disease Resistance Evaluation of a New Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) Strain Resistant to Largemouth Bass Virus (LMBV). Animals. 2025; 15(24):3510. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243510

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Wenxian, Pinhong Li, Xia Luo, Ningqiu Li, Qiang Lin, Hongru Liang, Yinjie Niu, Baofu Ma, Wenwen Xiao, and Xiaozhe Fu. 2025. "Breeding and Disease Resistance Evaluation of a New Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) Strain Resistant to Largemouth Bass Virus (LMBV)" Animals 15, no. 24: 3510. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243510

APA StyleLi, W., Li, P., Luo, X., Li, N., Lin, Q., Liang, H., Niu, Y., Ma, B., Xiao, W., & Fu, X. (2025). Breeding and Disease Resistance Evaluation of a New Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) Strain Resistant to Largemouth Bass Virus (LMBV). Animals, 15(24), 3510. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243510