Early-Life Socialization Enhances Social Competence and Alters Affiliative Preference in Piglets

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Housing

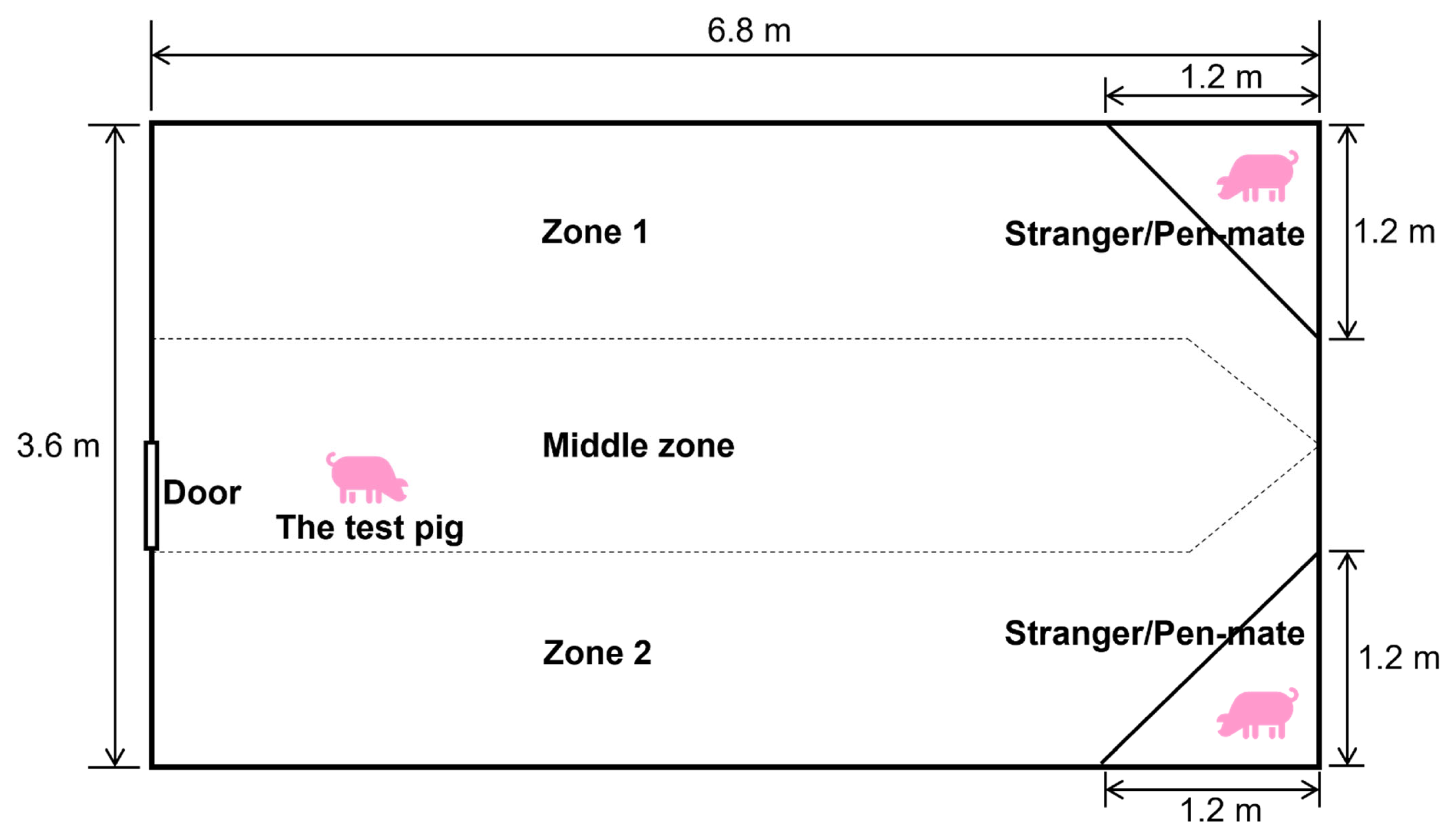

2.2. Social Preference Test

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

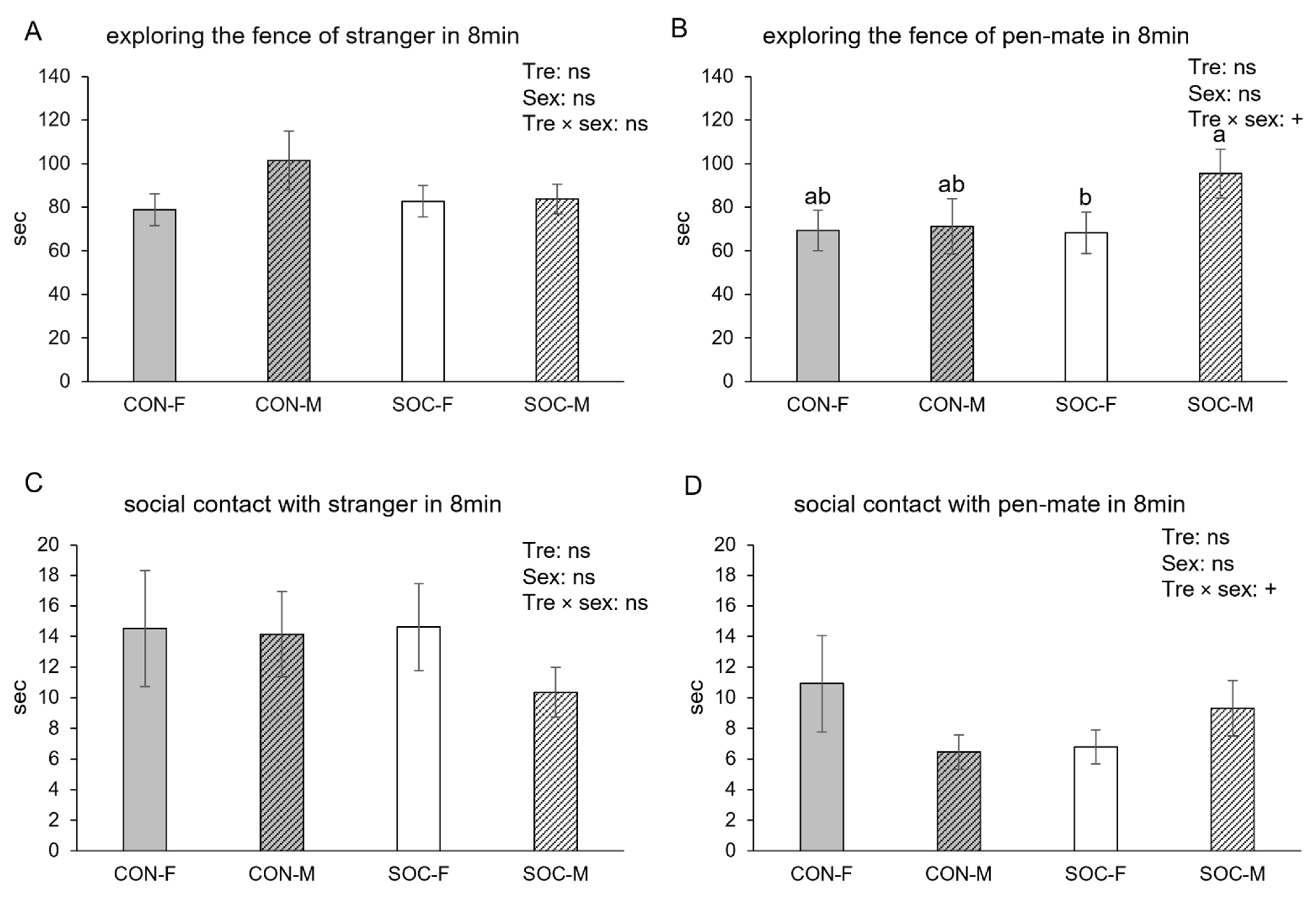

3.1. The Entire Test (8 Min)

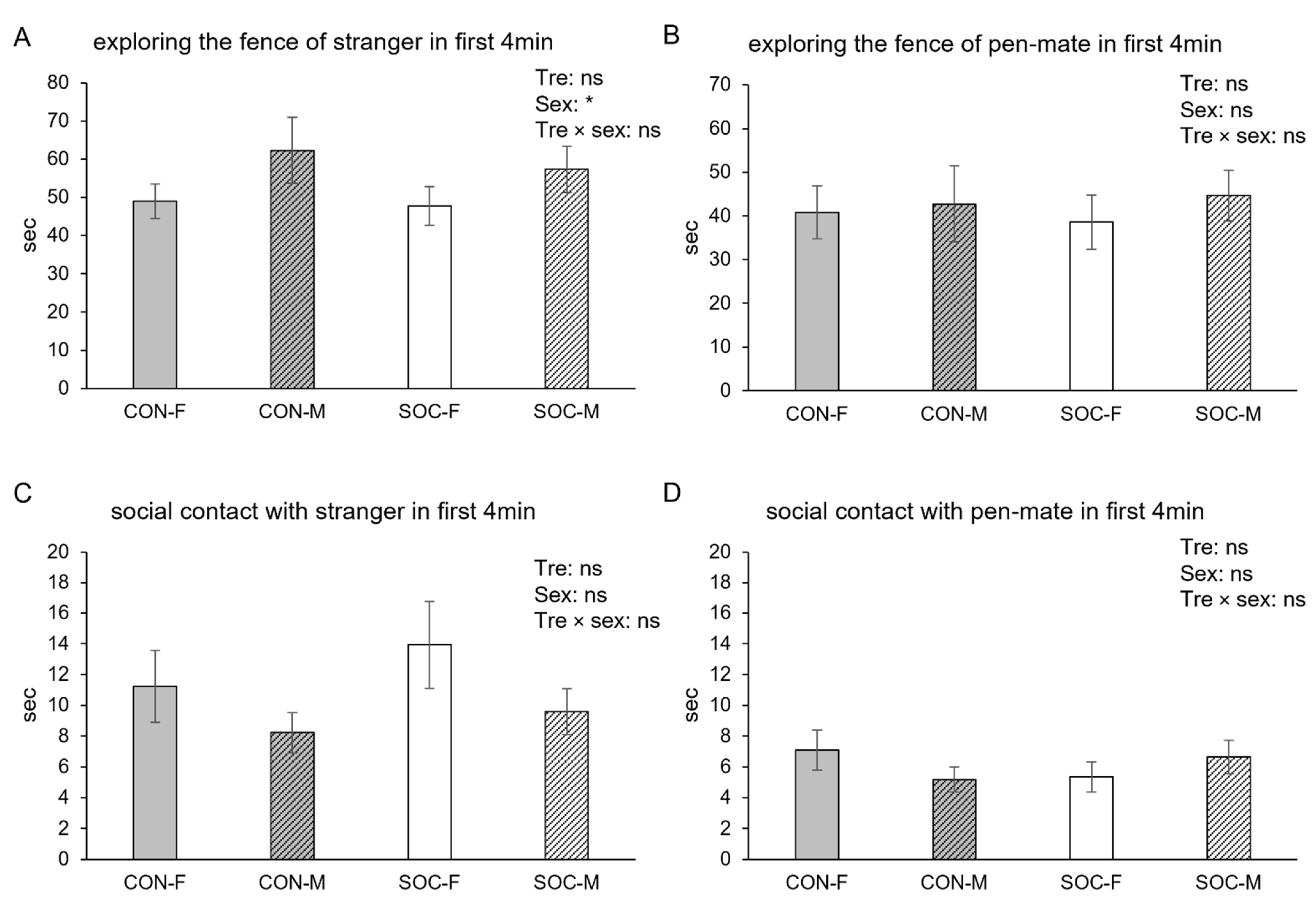

3.2. The First Half of the Test

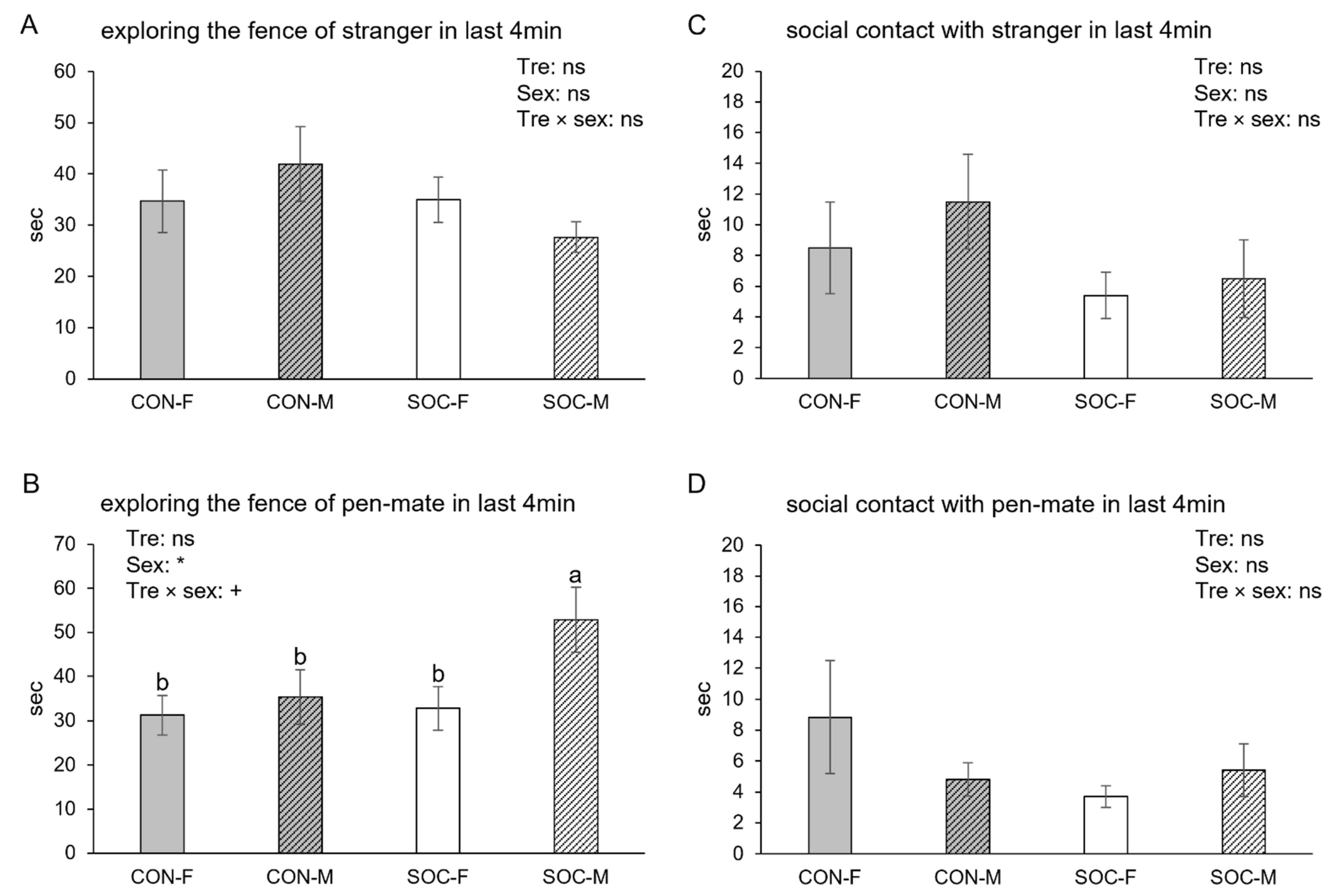

3.3. The Last Half of the Test

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Campbell, J.M.; Crenshaw, J.D.; Polo, J. The biological stress of early weaned piglets. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2013, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerlink, I.; Farish, M.; D’Eath, R.B.; Arnott, G.; Turner, S.P. Long Term Benefits on Social Behavior after Early Life Socialization of Piglets. Animals 2018, 8, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Kerschaver, C.; Turpin, D.; Michiels, J.; Pluske, J. Reducing Weaning Stress in Piglets by Pre-Weaning Socialization and Gradual Separation from the Sow: A Review. Animals 2023, 13, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, H.L.; Lopez-Verge, S.; Chong, Q.; Gasa, J.; Manteca, X.; Llonch, P. Short communication: Preweaning socialization and environmental enrichment affect short-term performance after regrouping in commercially reared pigs. Animal 2021, 15, 100115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, W.; Bi, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Liu, R.; Zhang, X.; Shu, Y.; Li, X.; Bao, J.; Liu, H. Impact of early socialization environment on social behavior, physiology and growth performance of weaned piglets. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 238, 105314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, L.C.; Ko, H.; Yang, C.; Llonch, L.; Manteca, X.; Camerlink, I.; Llonch, P. Early socialisation as a strategy to increase piglets’ social skills in intensive farming conditions. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 206, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, J.E.; Camerlink, I.; Turner, S.P.; Farish, M.; Arnott, G. Socialisation and its effect on play behavior and aggression in the domestic pig (Sus scrofa). Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutzer, T.; Bünger, B.; Kjaer, J.B.; Schrader, L. Effects of early contact between non-littermate piglets and of the complexity of farrowing conditions on social behavior and weight gain. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 121, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrey, L.; Kemper, N.; Fels, M. Behavior and skin injuries of piglets originating from a novel group farrowing system before and after weaning. Agriculture 2019, 9, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerlink, I.; Farish, M.; Arnott, G.; Turner, S.P. Sexual dimorphism in ritualized agonistic behavior, fighting ability and contest costs of Sus scrofa. Front. Zool. 2022, 19, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakawa, H. Revisiting sociability: Factors facilitating approach and avoidance during the three-chamber test. Physiol. Behav. 2023, 272, 114373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubry, A.V.; Joseph, B.C.; Goodwin, N.L.; Li, L.; Navarrete, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tsai, V.; Durand-de, C.R.; Golden, S.A.; Russo, S.J. Sex differences in appetitive and reactive aggression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022, 47, 1746–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fels, M.; Schrey, L.; Rauterberg, S.; Kemper, N. Early socialisation in group lactation system reduces post-weaning aggression in piglets. Vet. Rec. 2021, 189, e830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdon, M.; Morrison, R.S.; Hemsworth, P.H. Rearing piglets in multi-litter group lactation systems: Effects on piglet aggression and injuries post-weaning. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 183, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S.P.; Weller, J.E.; Camerlink, I.; Arnott, G.; Choi, T.; Doeschl-Wilson, A.; Farish, M.; Foister, S. Play fighting social networks do not predict injuries from later aggression. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, J.E.; Turner, S.P.; Futro, A.; Donbavand, J.; Brims, M.; Arnott, G. The influence of early life socialisation on cognition in the domestic pig (Sus scrofa domestica). Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerlink, I.; Turner, S.P.; Farish, M.; Arnott, G. Advantages of social skills for contest resolution. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2019, 6, 181456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlone, J.J. Influence of resources on pig aggression and dominance. Behav. Process. 1986, 12, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhim, S.J.; Son, S.H.; Hwang, H.S.; Lee, J.K.; Hong, J.K. Effects of Mixing on the Aggressive Behavior of Commercially Housed Pigs. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 28, 1038–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolhuis, J.E.; Schouten, W.G.; Schrama, J.W.; Wiegant, V.M. Individual coping characteristics, aggressiveness and fighting strategies in pigs. Anim. Behav. 2005, 69, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Eath, R.; Burn, C. Individual differences in behavior: A test of’coping style’does not predict resident-intruder aggressiveness in pigs. Behavior 2002, 139, 1175–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clouard, C.; Resmond, R.; Prunier, A.; Tallet, C.; Merlot, E. Exploration of early social behaviors and social styles in relation to individual characteristics in suckling piglets. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimert, I.; Rodenburg, T.B.; Ursinus, W.W.; Kemp, B.; Bolhuis, J.E. Responses to novel situations of female and castrated male pigs with divergent social breeding values and different backtest classifications in barren and straw-enriched housing. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 151, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rault, J. Friends with benefits: Social support and its relevance for farm animal welfare. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2012, 136, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friel, M.; Kunc, H.P.; Griffin, K.; Asher, L.; Collins, L.M. Positive and negative contexts predict duration of pig vocalisations. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimert, I.; Bolhuis, J.E.; Kemp, B.; Rodenburg, T.B. Indicators of positive and negative emotions and emotional contagion in pigs. Physiol. Behav. 2013, 109, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Behavior | Definition |

|---|---|

| Posture class | |

| Standing alert | Standing motionless |

| Standing | Standing with four paws on the floor |

| Walking | Walking |

| Lying | Lying on the floor |

| Other posture | Sitting or kneeling |

| Behavior class | |

| Exploring environment | Exploring the floor or wall of the arena by sniffing, nosing, licking or rooting with the rooting disc, except the areas with the familiar and unfamiliar pigs |

| Exploring the fence of the pen-mate a | Exploring the fence behind which the pen-mate is placed by sniffing, nosing, licking or rooting with the rooting disc |

| Exploring the fence of the stranger a | Exploring the fence behind which the unfamiliar pig is placed by sniffing, nosing, licking or rooting with the rooting disc |

| Social contact with the pen-mate a | Touching or sniffing any part of the pen-mate, including nose contact |

| Social contact with the stranger a | Touching or sniffing any part of the unfamiliar pig in the fence, including nose contact |

| Aggression directed at the pen-mate a | Fighting; horizontal or vertical knocking with the head or forward thrusting with the snout towards the pen-mate; intense ramming or pushing the pen-mate; biting the pen-mate |

| Aggression directed at the stranger a | Fighting; horizontal or vertical knocking with the head or forward thrusting with the snout towards the unfamiliar pig; intense ramming or pushing the unfamiliar pig; biting the unfamiliar pig |

| Defecating b | Defecation |

| Urinating b | Urinating |

| Other behavior | All other behaviors which are not described above |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luo, L.; Li, Z.; Bolhuis, J.E.; Wang, Y.; Wu, D.; Li, Y.; Li, C. Early-Life Socialization Enhances Social Competence and Alters Affiliative Preference in Piglets. Animals 2025, 15, 3395. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233395

Luo L, Li Z, Bolhuis JE, Wang Y, Wu D, Li Y, Li C. Early-Life Socialization Enhances Social Competence and Alters Affiliative Preference in Piglets. Animals. 2025; 15(23):3395. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233395

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuo, Lu, Zhengyu Li, Jantina Elizabeth Bolhuis, Yuyan Wang, Dongsheng Wu, Yansen Li, and Chunmei Li. 2025. "Early-Life Socialization Enhances Social Competence and Alters Affiliative Preference in Piglets" Animals 15, no. 23: 3395. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233395

APA StyleLuo, L., Li, Z., Bolhuis, J. E., Wang, Y., Wu, D., Li, Y., & Li, C. (2025). Early-Life Socialization Enhances Social Competence and Alters Affiliative Preference in Piglets. Animals, 15(23), 3395. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233395