Study on the Development and Formation Specifics of Longissimus Dorsi Muscles in Ziwuling Black Goats

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Location and Time

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Histo- and Morphlolgical Analysis

2.4. Immunofluorescence Staining

2.4.1. Deparaffinization of Paraffin Sections to Water

2.4.2. Antigen Retrieval

2.4.3. Circle Drawing and Serum Blocking

2.4.4. Primary and Secondary Antibody Incubation

2.4.5. DAPI Counterstaining and Mounting

2.4.6. Image Acquisition

2.5. Transcriptome Sequencing Analysis of Goat Longissimus Dorsi Muscle

2.5.1. RNA Extraction, Library Construction, and Sequencing

2.5.2. Alignment with Reference Genome

2.5.3. Functional Annotation Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

2.5.4. Validation by Real-Time Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

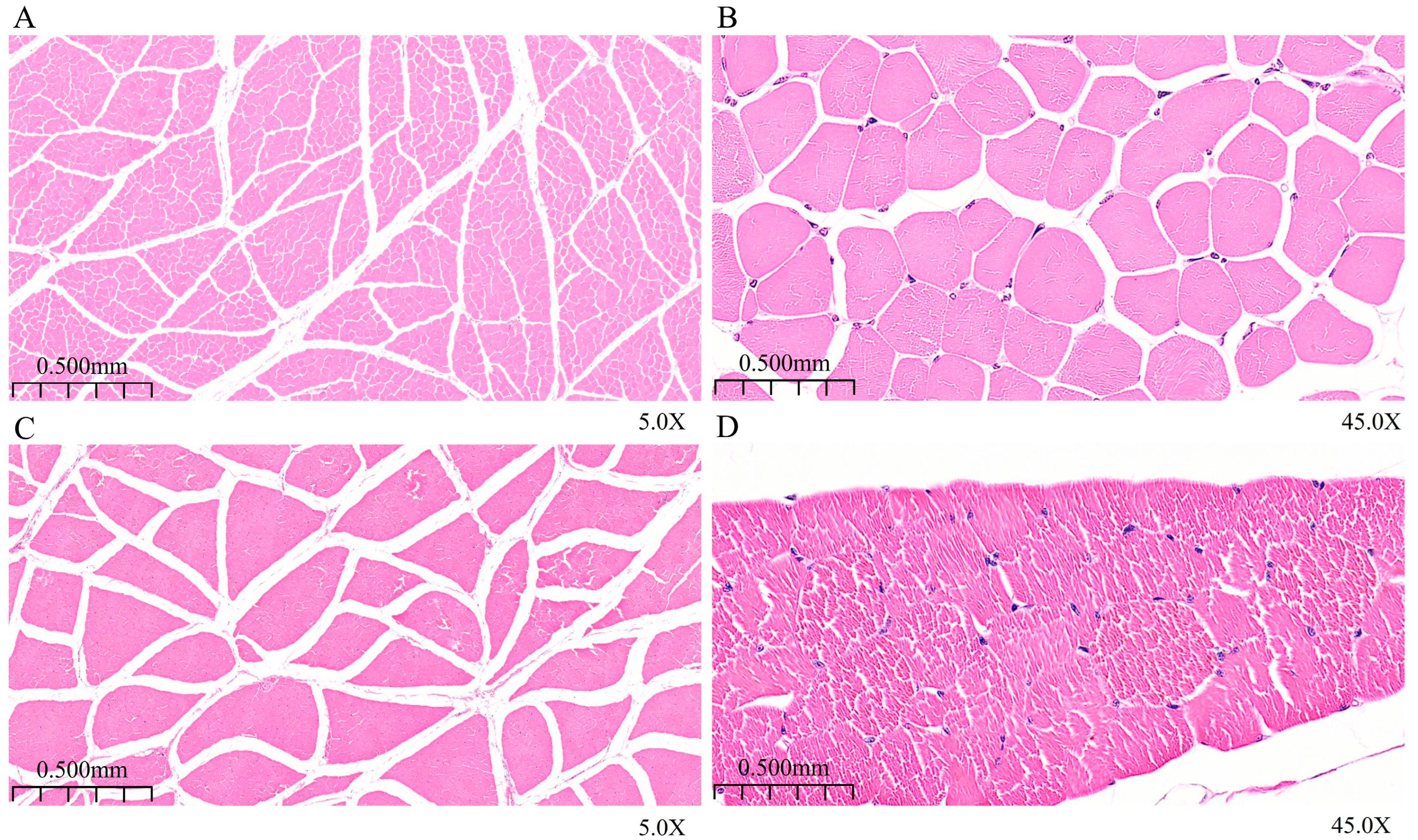

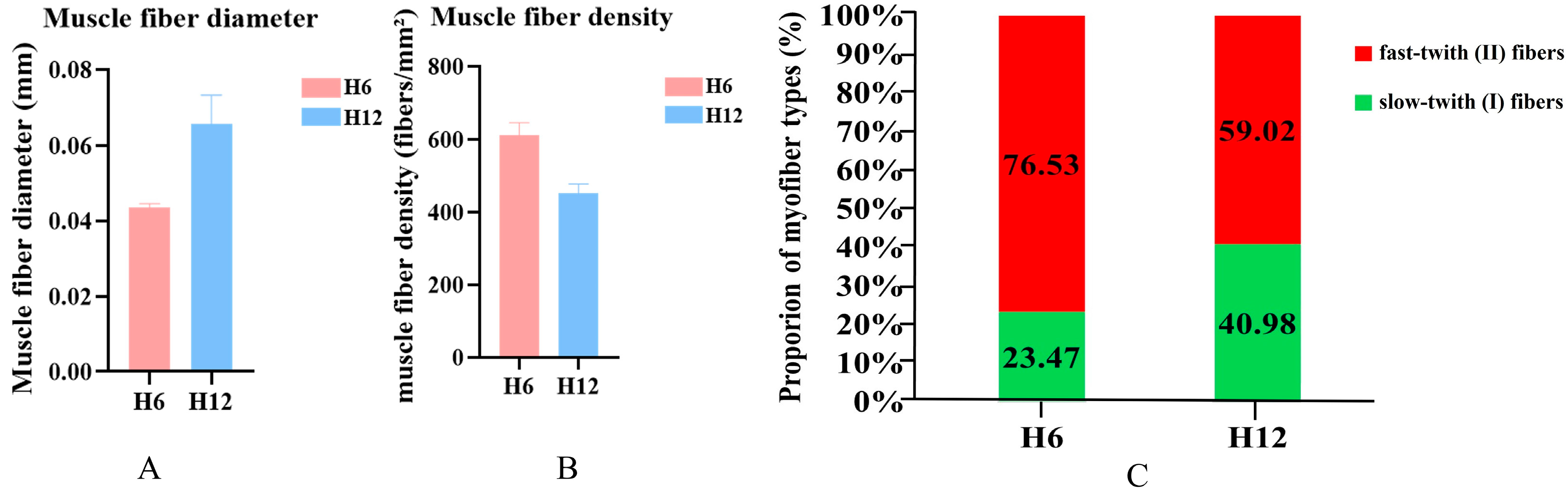

3.1. Analysis of Morphological Characteristics of Longissimus Dorsi Muscle

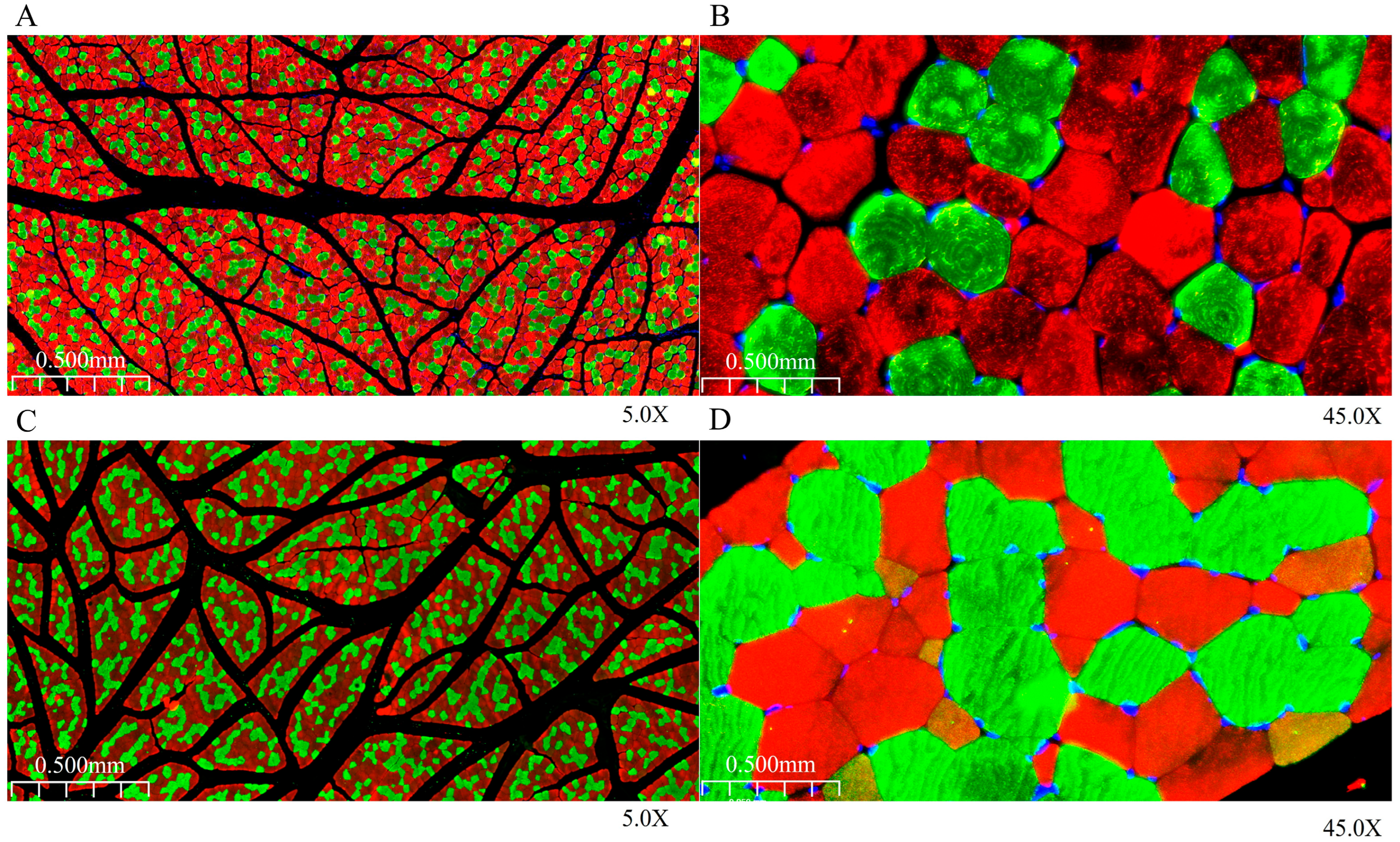

3.2. Analysis of Immunofluorescence Staining Characteristics of Longissimus Dorsi Muscle

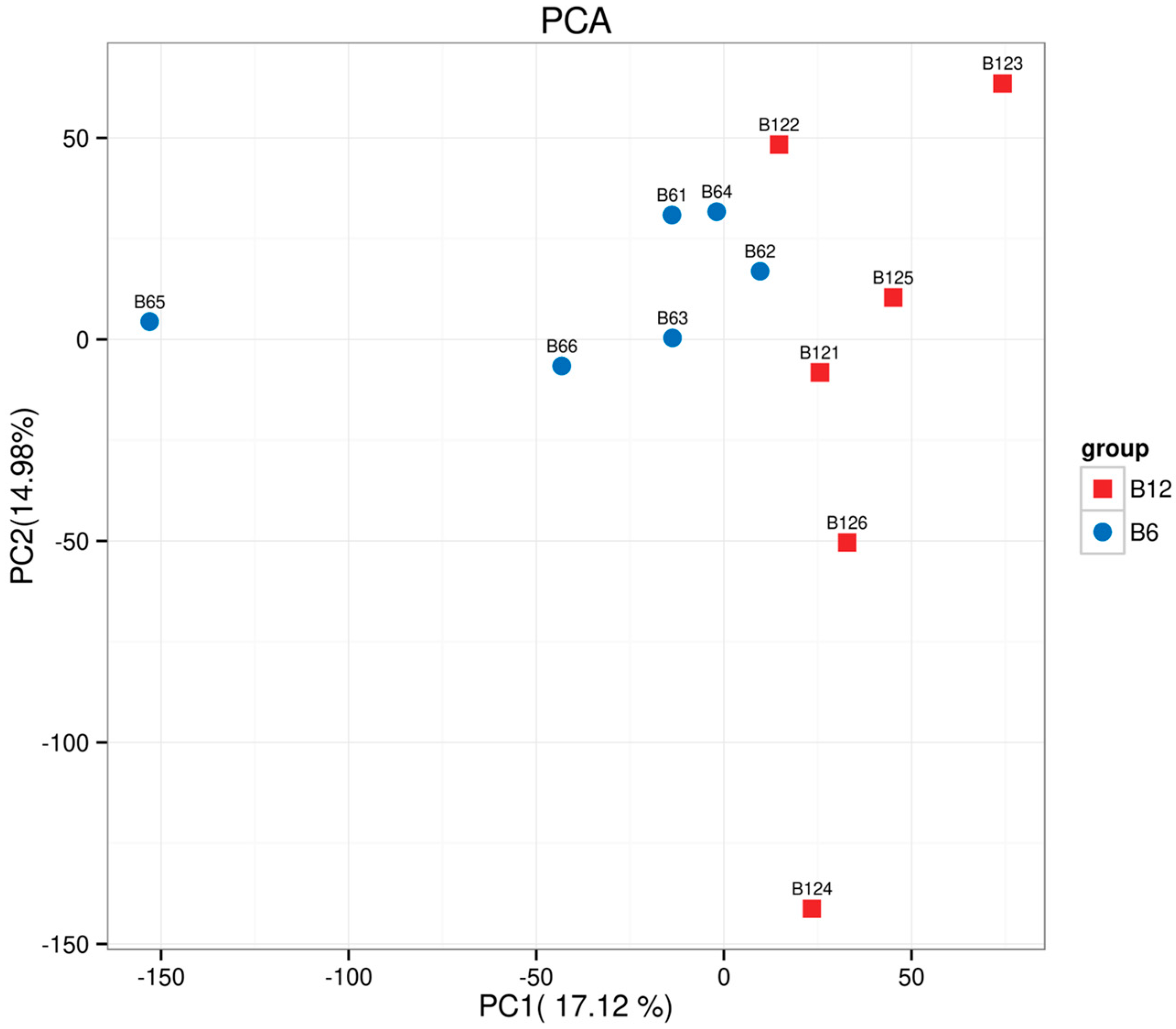

3.3. Quality Assessment of Longissimus Dorsi Muscle RNA-Seq Data

3.4. Alignment of Longissimus Dorsi Muscle RNA-Seq Data with Reference Genome

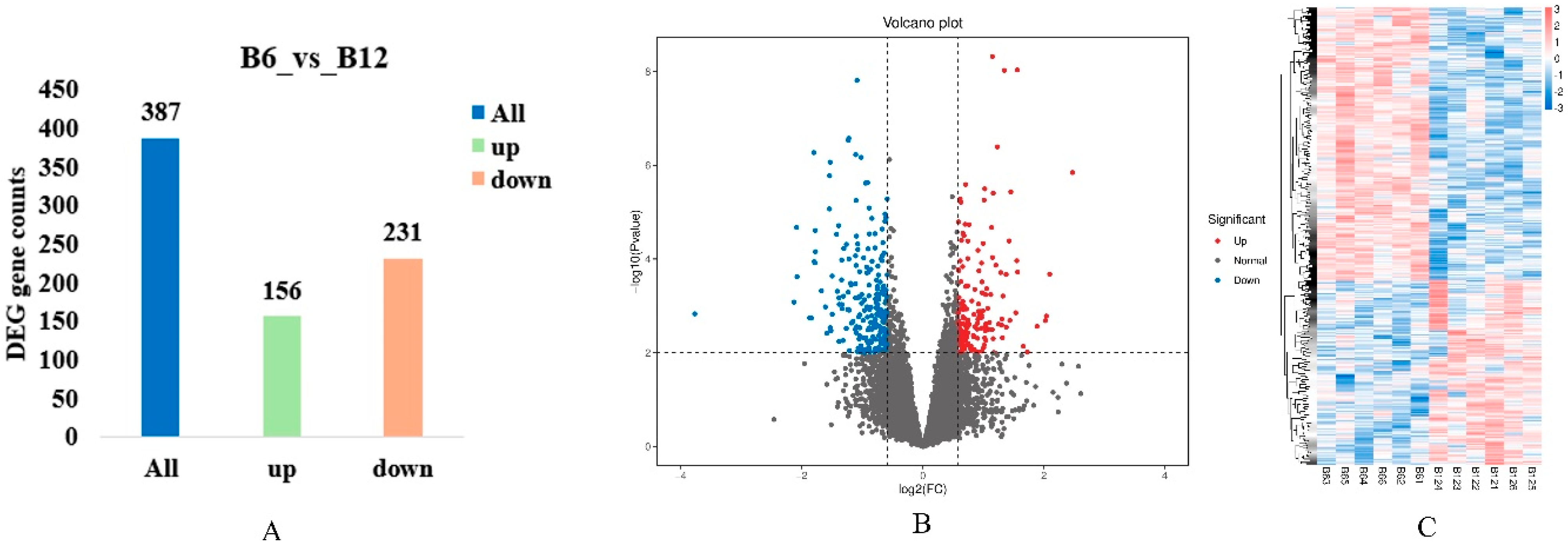

3.5. Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes

3.6. Functional Annotation of Differentially Expressed Genes

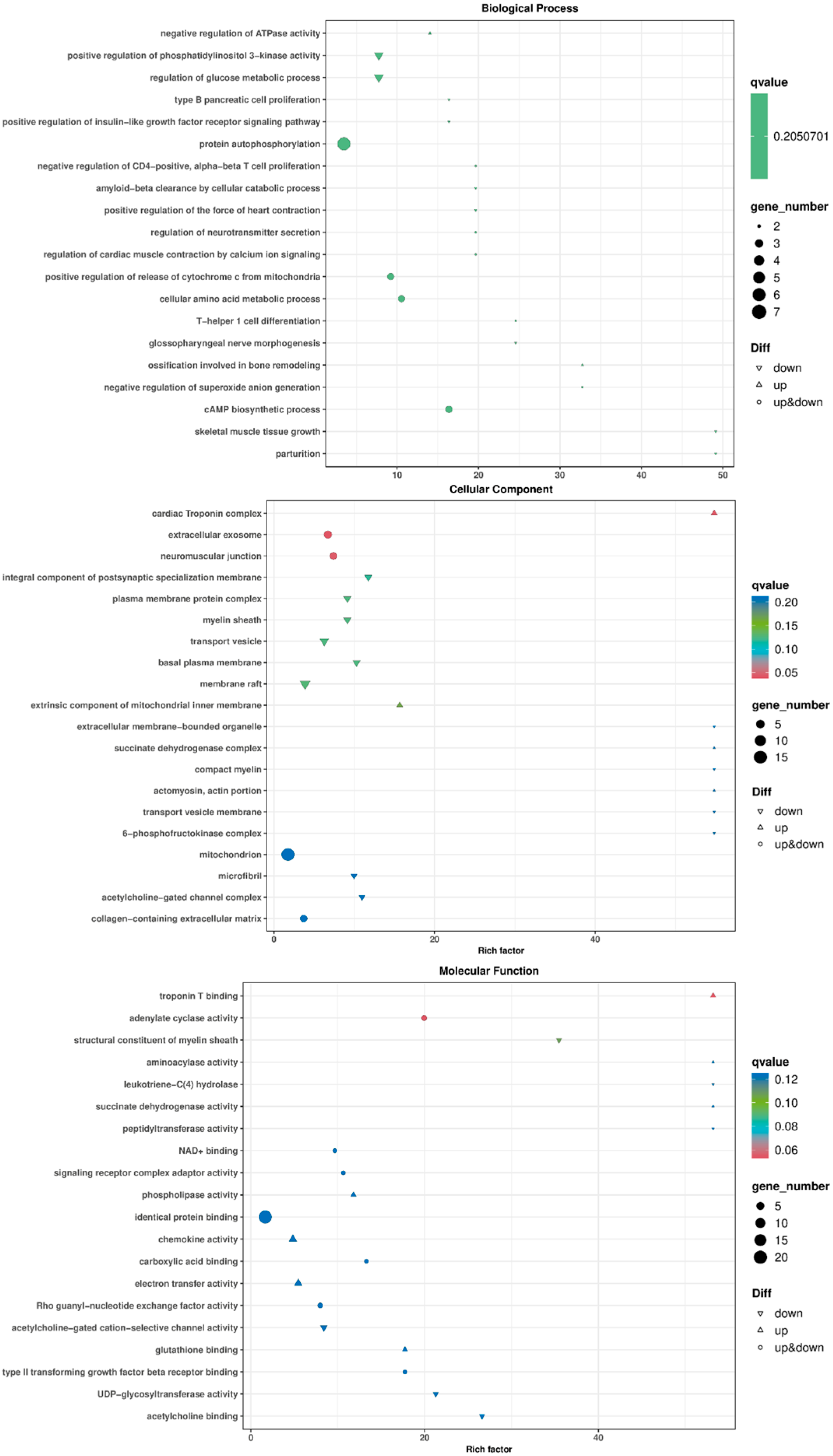

3.6.1. GO Enrichment Analysis

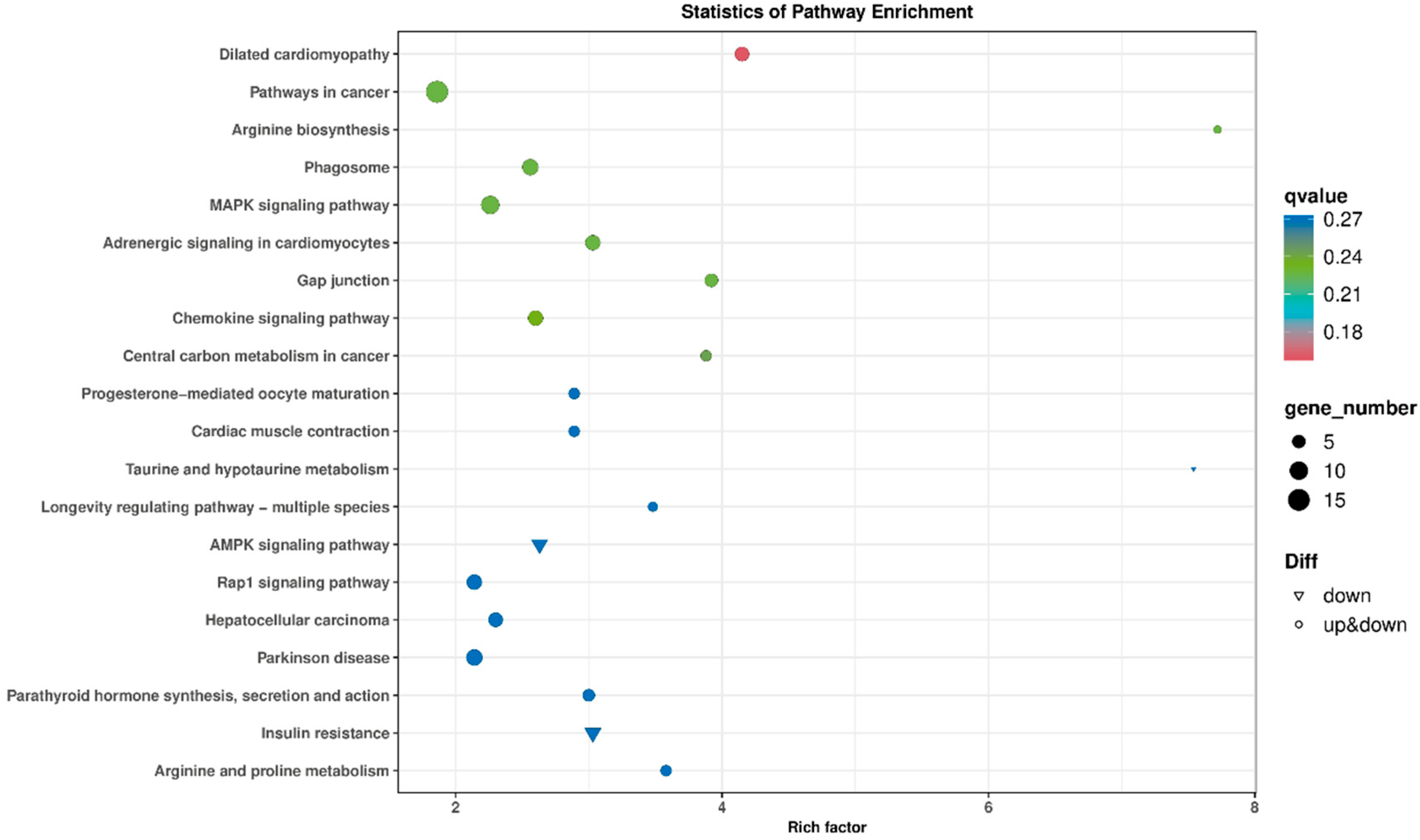

3.6.2. KEGG Signaling Pathway Enrichment Analysis

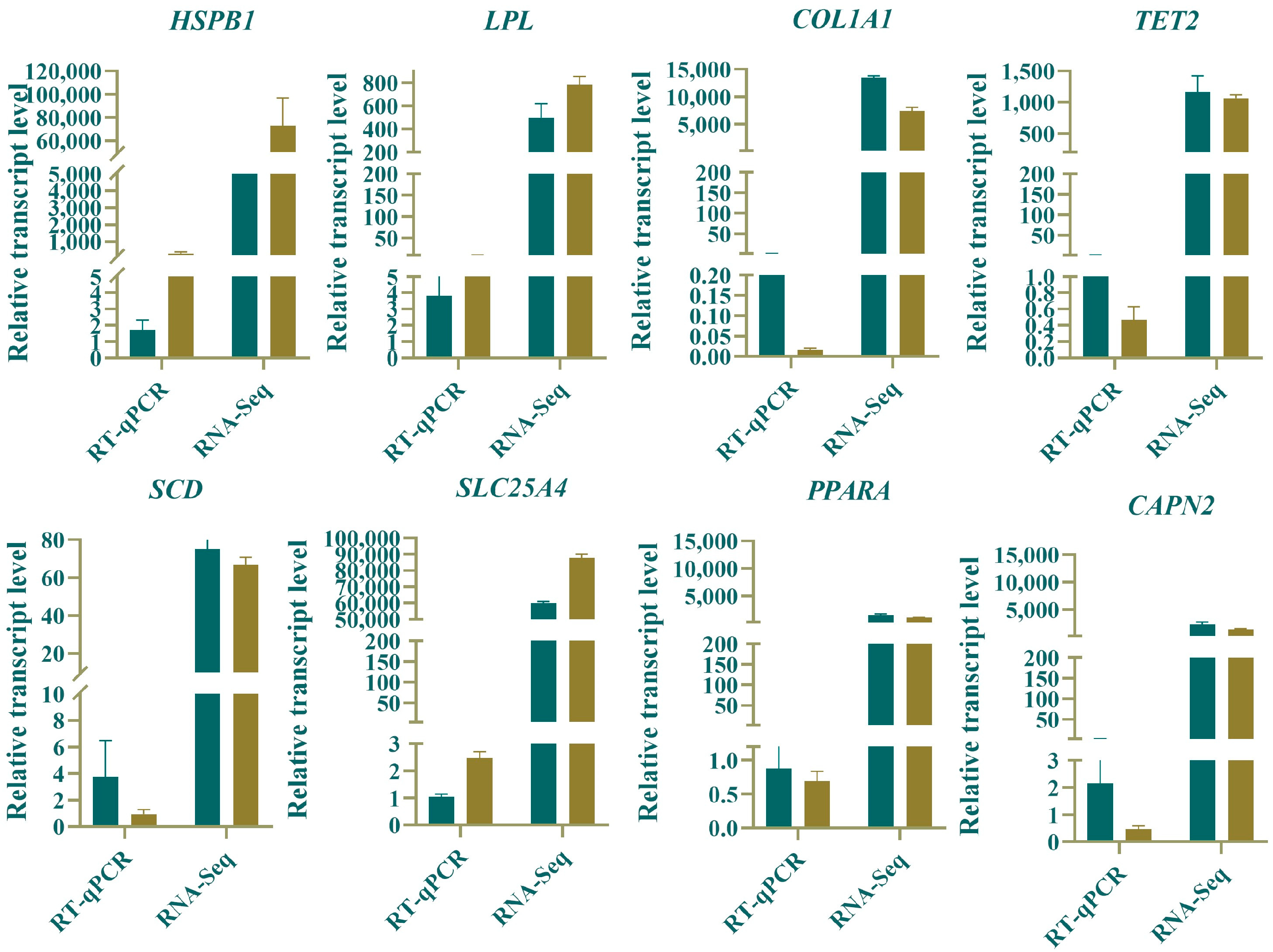

3.7. RT-qPCR Validation

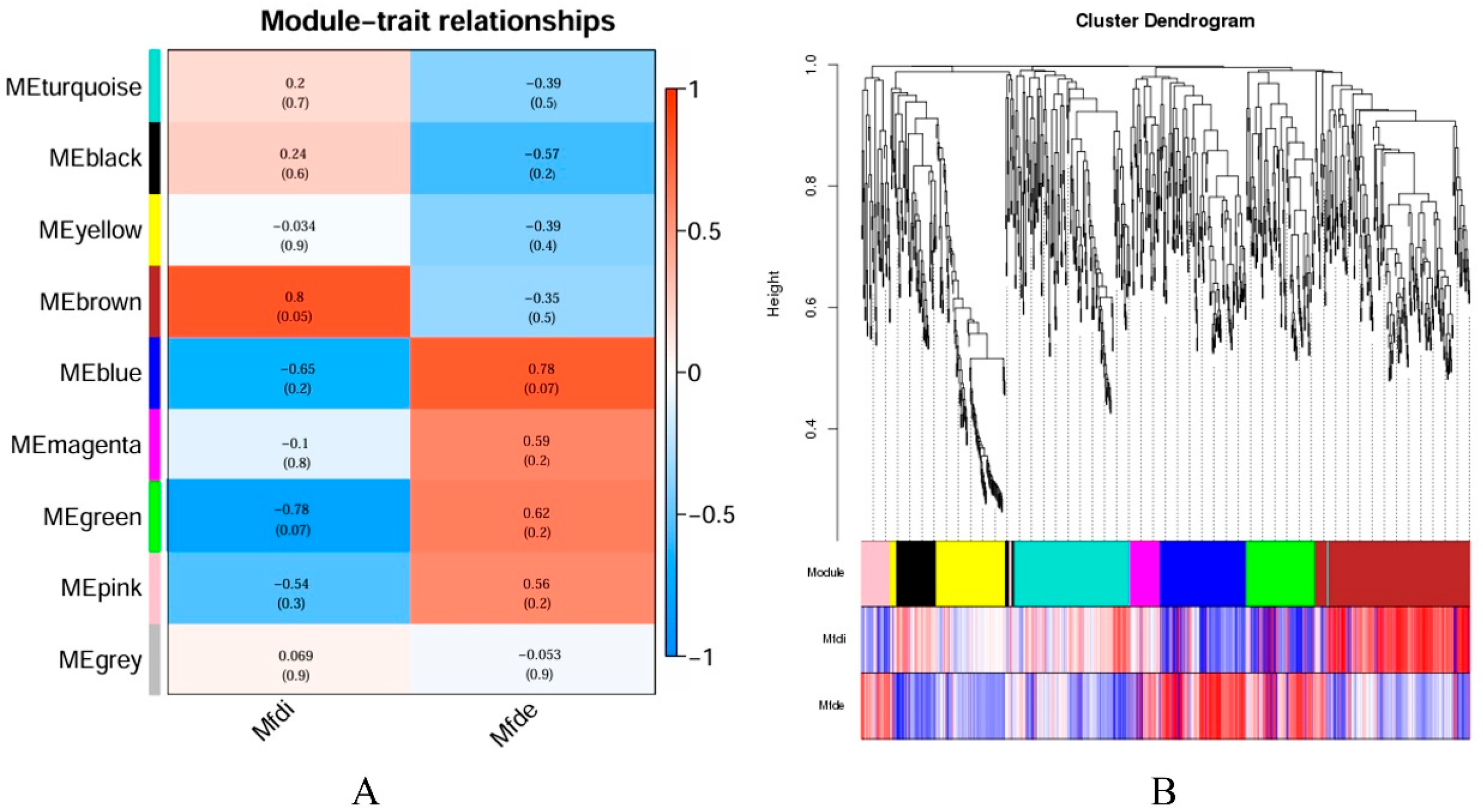

3.8. Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Listrat, A.; Lebret, B.; Louveau, I.; Astruc, T.; Bonnet, M.; Lefaucheur, L.; Picard, B.; Bugeon, J. How muscle structure and composition influence meat and flesh quality. Sci. World J. 2016, 2016, 3182746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Han, X.; Tan, D.; Chen, J.; Lai, C.; Yang, X.; Shan, X.; Silva, L.; Jiang, H. Effects of muscle fiber composition on meat quality, flavor characteristics, and nutritional traits in lamb. Foods 2025, 14, 2309–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yuan, L.; Song, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y. Distribution of extracellular matrix related proteins in normal and cryptorchid ziwuling black goat testes. Anim. Reprod. 2022, 19, e20220005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Luo, Y.; Wang, J.; Hu, J.; Liu, X.; Li, S.; Hao, Z.; Li, M.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Integrated transcriptome analysis reveals roles of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) in caprine skeletal muscle mass and meat quality. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2023, 23, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Hao, Z.; Wang, J.; Hu, J.; Liu, X.; Li, S.; Ke, N.; Song, Y.; Lu, Y.; Hu, L.; et al. Comparative transcriptome profile analysis of longissimus dorsi muscle tissues from two goat breeds with different meat production performance using RNA-seq. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 619399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candek-Potokar, M.; Lefaucheur, L.; Zlender, B.; Bonneau, M. Effect of slaughter weight and/or age on histological characteristics of pig longissimus dorsi muscle as related to meat quality. Meat Sci. 1999, 52, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Lu, X.; Sun, X.; Jiang, H.; Chen, Y. Preliminary studies on the molecular mechanism of intramuscular fat deposition in the longest dorsal muscle of sheep. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozawa, S.; Mitsuhashi, T.; Mitsumoto, M.; Matsumoto, S.; Itoh, N.; Itagaki, K.; Kohno, Y.; Dohgo, T. The characteristics of muscle fiber types of longissimus thoracis muscle and their influences on the quantity and quality of meat from japanese black steers. Meat Sci. 2000, 54, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yue, F.; Kuang, S. Muscle histology characterization using h&e staining and muscle fiber type classification using immunofluorescence staining. Bio Protoc. 2017, 7, e2279. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H.; Joo, S.T.; Ryu, Y.C. Skeletal muscle fiber type and myofibrillar proteins in relation to meat quality. Meat Sci. 2010, 86, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiaffino, S.; Reggiani, C. Fiber types in mammalian skeletal muscles. Physiol. Rev. 2011, 91, 1447–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavaux, D.; Art, T.; McEntee, K.; Reznick, M.; Lekeux, P. Muscle fibre type and size, and muscle capillary density in young double-muscled blue belgian cattle. Zentralbl Veterinarmed A 1994, 41, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqin, Q.; Nishiumi, T.; Yamada, T.; Wang, S.; Liu, W.; Wu, R.; Borjigin, G. Relationships among muscle fiber type composition, fiber diameter and MRF gene expression in different skeletal muscles of naturally grazing wuzhumuqin sheep during postnatal development. Anim. Sci. J. 2017, 88, 2033–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Gao, H.; He, J.; Yu, A.; Sun, C.; Xie, Y.; Yao, H.; Wang, H.; Duan, Y.; Hu, J.; et al. Effects of dietary allium mongolicum regel powder supplementation on the growth performance, meat quality, antioxidant capacity and muscle fibre characteristics of fattening angus calves under heat stress conditions. Food Chem. 2024, 453, 139539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yu, A.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, X.; Guo, B.; Xu, L.; Tao, W.; Yang, R.; Sun, C.; Hu, J.; et al. Electronic nose, flavoromics, and lipidomics reveal flavor changes in longissimus thoracis of fattening saanen goats by dietary allium mongolicum regel flavonoids. Food Chem. X 2025, 29, 102752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Chen, S.; Niu, S.; Bi, X.; Qiao, L.; Yang, K.; Liu, J.; Liu, W. Hybrid sequencing in different types of goat skeletal muscles reveals genes regulating muscle development and meat quality. Animals 2021, 11, 2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Ai, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Long, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, L.; Gu, Q.; Han, H. Genome-wide epigenetic dynamics during postnatal skeletal muscle growth in hu sheep. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, W.; Weng, K.; Gu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, G.; Xu, Q. Effect of muscle fiber characteristics on meat quality in fast- and slow-growing ducks. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Wen, Y.; Li, X.; Peng, W.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Yang, P.; Chen, N.; Lei, C.; Zhang, J.; et al. Bovine enhancer-regulated circSGCB acts as a ceRNA to regulate skeletal muscle development via enhancing KLF3 expression. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 261, 129779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Li, F.; Cao, H.; Zhang, X.; Yu, D.; He, Z.; Ji, H.; Lv, K.; Wu, G.; et al. The integration of genome-wide DNA methylation and transcriptomics identifies the potential genes that regulate the development of skeletal muscles in ducks. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, X.; Huang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Lin, X. An improvement of the 2^(-delta delta CT) method for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction data analysis. Biostat. Bioinf. Biomath. 2013, 3, 71–85. [Google Scholar]

- Picard, B.; Gagaoua, M. Muscle fiber properties in cattle and their relationships with meat qualities: An overview. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 6021–6039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, F.V.; Michel, G.; Gruschwitz, F. Development of fiber type composition and fiber diameter in the longissimus muscle of the domestic pig (sus scrofa domesticus). Anat. Anz. 1983, 154, 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Ai, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Long, X.; Gu, Q.; Han, H. Dynamic changes in the global transcriptome of postnatal skeletal muscle in different sheep. Genes 2023, 14, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, M.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Shen, W.; Zhang, L.; Lin, S. Molecular mechanisms underlying the impact of muscle fiber types on meat quality in livestock and poultry. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1284551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Z.; Yue, Y.; Shi, H.; Zhang, J.; Liu, T.; Liu, J.; Yang, B. Effects of sheep sires on muscle fiber characteristics, fatty acid composition and volatile flavor compounds in f(1) crossbred lambs. Foods 2022, 11, 4076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Q.; Du, Z.Q. Advances in the discovery of genetic elements underlying longissimus dorsi muscle growth and development in the pig. Anim. Genet. 2023, 54, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, R.; Siddaraju, N.K.; Manjunatha, S.S.; Sudarshan, S.; Fairoze, M.N.; Kumar, A.; Chhabra, P.; Kaur, M.; Sreesujatha, R.M.; Ahlawat, S.; et al. Muscle transcriptome provides the first insight into the dynamics of gene expression with progression of age in sheep. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Sha, Y.; Chen, Q.; Chen, X.; Gao, M.; Liu, X.; He, Y.; Gao, X.; Hu, J.; Wang, J.; et al. The interaction between rumen microbiota and neurotransmitters plays an important role in the adaptation of phenological changes in tibetan sheep. BMC Vet. Res. 2025, 21, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xin, C.; Wang, S.; Zhuo, S.; Zhu, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Chen, Y. Lactate transported by MCT1 plays an active role in promoting mitochondrial biogenesis and enhancing TCA flux in skeletal muscle. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, 4508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liang, X.; Zhou, D.; Lai, L.; Xiao, L.; Liu, L.; Fu, T.; Kong, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Vega, R.B.; et al. Coupling of mitochondrial function and skeletal muscle fiber type by a mir-499/fnip1/AMPK circuit. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016, 8, 1212–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farha, S.; Comhair, S.; Hou, Y.; Park, M.M.; Sharp, J.; Peterson, L.; Willard, B.; Zhang, R.; DiFilippo, F.P.; Neumann, D.; et al. Metabolic endophenotype associated with right ventricular glucose uptake in pulmonary hypertension. Pulm. Circ. 2021, 11, 20458940–211054325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.Y.; Sun, C.Y.; Zhao, R.; Guan, X.L.; Li, M.L.; Zhang, F.; Wan, Z.H.; Feng, J.X.; Yin, M.; Lei, Q.Y.; et al. BAG2 releases SAMD4b upon sensing of arginine deficiency to promote tumor cell survival. Mol. Cell 2025, 85, 2581–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Meininger, C.J.; McNeal, C.J.; Bazer, F.W.; Rhoads, J.M. Role of l-arginine in nitric oxide synthesis and health in humans. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1332, 167–187. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karna, E.; Szoka, L.; Huynh, T.; Palka, J.A. Proline-dependent regulation of collagen metabolism. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 1911–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Fang, B.; Shan, S.; Li, Q. Mechanical stiffness promotes skin fibrosis through piezo1-mediated arginine and proline metabolism. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzig, S.; Shaw, R.J. AMPK: Guardian of metabolism and mitochondrial homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Yan, X.; Bai, Y.; Sun, L.; Zhao, L.; Jin, Y.; Su, L. Lactobacillus improves meat quality in sunit sheep by affecting mitochondrial biogenesis through the AMPK pathway. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1030485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancura, A.; Nagar, S.; Kaur, P.; Bu, P.; Bhagwat, M.; Vancurova, I. Reciprocal regulation of AMPK/SNF1 and protein acetylation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senatus, L.; Egana-Gorrono, L.; Lopez-Diez, R.; Bergaya, S.; Aranda, J.F.; Amengual, J.; Arivazhagan, L.; Manigrasso, M.B.; Yepuri, G.; Nimma, R.; et al. DIAPH1 mediates progression of atherosclerosis and regulates hepatic lipid metabolism in mice. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, K.; Kato, H.; Kurata, R.; Qianwen, L.; Hayakawa, T.; Okada, F.; Fujita, F.; Nakagawa, Y.; Tanemura, A.; Murota, H.; et al. Gap junction-mediated contraction of myoepithelial cells induces the peristaltic transport of sweat in human eccrine glands. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simko, V.; Iuliano, F.; Sevcikova, A.; Labudova, M.; Barathova, M.; Radvak, P.; Pastorekova, S.; Pastorek, J.; Csaderova, L. Hypoxia induces cancer-associated cAMP/PKA signalling through HIF-mediated transcriptional control of adenylyl cyclases VI and VII. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Zhao, J.; Li, F.; Zhao, X.; Feng, J.; Su, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhao, J. Vitamin a regulates mitochondrial biogenesis and function through p38 MAPK-PGC-1alpha signaling pathway and alters the muscle fiber composition of sheep. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Vega, A.; Cobb, M.H. Navigating the ERK1/2 MAPK cascade. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Nicolet, J. Specificity models in MAPK cascade signaling. FEBS Open Bio 2023, 13, 1177–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charo, I.F.; Ransohoff, R.M. The many roles of chemokines and chemokine receptors in inflammation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yu, M.; Deng, J.; Lv, X.; Liu, J.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C. Chemokine signaling pathway involved in CCL2 expression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Yonsei Med. J. 2015, 56, 1134–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graca, F.A.; Stephan, A.; Minden-Birkenmaier, B.A.; Shirinifard, A.; Wang, Y.D.; Demontis, F.; Labelle, M. Platelet-derived chemokines promote skeletal muscle regeneration by guiding neutrophil recruitment to injured muscles. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tidball, J.G. Regulation of muscle growth and regeneration by the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchert, M.; Koch, C.; Zieger, K.; Engele, J. Identification of CXCL11 as part of chemokine network controlling skeletal muscle development. Cell Tissue Res. 2021, 384, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagiv, A.; Krizhanovsky, V. Immunosurveillance of senescent cells: The bright side of the senescence program. Biogerontology 2013, 14, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.H.; Han, N.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Q. Gadd45a knockdown alleviates oxidative stress through suppressing the p38 MAPK signaling pathway in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Placenta 2018, 65, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Fan, Y.; Liang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, G.; Deng, M.; Wang, Z.; Lu, J.; Shi, J.; Wang, F.; et al. FTO-mediated demethylation of GADD45b promotes myogenesis through the activation of p38 MAPK pathway. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2021, 26, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, S.; Cai, B.; Nie, Q. PGC-1alpha affects skeletal muscle and adipose tissue development by regulating mitochondrial biogenesis. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2022, 297, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Software Name | Version | Purpose in This Study |

|---|---|---|

| Image-Pro Plus | 6.0 | Mainly used for image analysis, including image acquisition and morphological processing |

| Excel | 2016 | Preliminary data organization |

| SPSS | 24.0 | Used for professional statistical analysis |

| GraphPad Prism | 9 | Used for scientific data statistics and high-quality charting |

| Gene | Primer Sequence | Primer Length | Annealing Temperature | Sequence Number | Primer Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSPB1 | F: CAAGTCAGCTACCCAGTCGG R: TGTTCGGACTTTCCGGCTTC | 93 | 60 °C | XM_018040903.1 | Fairly good |

| LPL | F: GAGGCCTTGGAGATGTGGAC R: AATTGCACCGGTACGCCTTA | 114 | 60 °C | NM_001285607.2 | |

| COL1A1 | F: AAATGGAGCTCCTGGTCAGATG R: AGCACCATCATTTCCTCTAGCAC | 100 | 60 °C | XM_018064895.1 | |

| TET2 | F: GCCTAACCCACCGACTCTTC R: CTTGCTGTTTGTGCCCCATC | 77 | 60 °C | XM_013964483.2 | |

| SCD | F: GTGCCGTGGTATCTATGGGG R: ACAACAGCGTACCGGAGAAG | 74 | 60 °C | NM_001285619.1 | |

| SLC25A4 | F: AGTTCACTGGTCTGGGCAAC R: TGGACCGAGACGTTGAAACC | 88 | 60 °C | XM_018042040.1 | |

| PPARA | F: TTCCCTCTTTGTGGCTGCTA R: GCGTCGTCAGGATGGTTGTT | 135 | 60 °C | XM_018048905.1 | |

| CAPN2 | F: CATCCGGGTCTTTTCCGAGA R: GATGTCGTCCTCGCTGATGT | 97 | 60 °C | XM_018060202.1 | |

| GAPDH | F: AAGGTCGGAGTGAACGGATT R: ACGATGTCCACTTTGCCAGTA | 80 | 60 °C | XM_005680968.3 |

| Group | Genes | Signaling Pathways | Expression |

|---|---|---|---|

| B6_vs_B12 | ACACB CPT1A | AMPK signaling pathway | Down |

| ADCY6 ADCY7 | Gap junction | Down | |

| NOS1 SMOX | Arginine and proline metabolism | Down |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, H.; Shi, F.; Gu, L.; Wang, Y.; Yue, Y.; Huang, W.; Yang, Y.; Sun, P.; Xue, W.; Zhang, X.; et al. Study on the Development and Formation Specifics of Longissimus Dorsi Muscles in Ziwuling Black Goats. Animals 2025, 15, 3265. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223265

Guo H, Shi F, Gu L, Wang Y, Yue Y, Huang W, Yang Y, Sun P, Xue W, Zhang X, et al. Study on the Development and Formation Specifics of Longissimus Dorsi Muscles in Ziwuling Black Goats. Animals. 2025; 15(22):3265. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223265

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Hailong, Fuyue Shi, Lingrong Gu, Yanyan Wang, Yangyang Yue, Wei Huang, Yongqiang Yang, Panlong Sun, Wenyong Xue, Xiaoqiang Zhang, and et al. 2025. "Study on the Development and Formation Specifics of Longissimus Dorsi Muscles in Ziwuling Black Goats" Animals 15, no. 22: 3265. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223265

APA StyleGuo, H., Shi, F., Gu, L., Wang, Y., Yue, Y., Huang, W., Yang, Y., Sun, P., Xue, W., Zhang, X., Zhu, X., Shao, P., He, Y., Xu, J., & Liu, X. (2025). Study on the Development and Formation Specifics of Longissimus Dorsi Muscles in Ziwuling Black Goats. Animals, 15(22), 3265. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223265