1. Introduction

The global livestock industry is under increasing pressure to reduce its environmental footprint, particularly regarding nitrogen emissions from pig production [

1]. Over 70% of pig feed comprises nitrogenous compounds, of which incomplete digestion leads to elevated nitrogen levels in feces [

2]. The subsequent volatilization of nitrogen as ammonia contributes significantly to atmospheric pollution [

3]. To address these challenges, low-protein diets (LPDs), also known as ideal amino acid diets, have emerged as a promising strategy to reduce nitrogen excretion while maintaining growth performance [

4,

5]. LPDs are designed to meet the specific amino acid requirements of animals at different growth stages by adjusting the types, quantities, and proportions of dietary amino acids. The concept of low-protein diets has been widely adopted in pigs, poultry, and other livestock species [

6,

7]. Compared to the dietary protein levels recommended by the National Research Council (NRC) in 1998 [

8], the NRC 2012 guidelines [

9] suggest a reduction in crude protein (CP) by 2–4% in pig diets. This highlights the considerable potential and advantages of LPDs in the swine industry. LPDs present a cost-effective alternative by reducing the cost of protein-rich feed ingredients while maintaining performance parameters, including growth rate, carcass characteristics, and meat quality [

10]. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that for every 1% decrease in dietary protein, total nitrogen excretion can be reduced by 8–10%, underscoring the value of LPDs as an environmentally friendly feeding strategy to mitigate nitrogen emissions and environmental pollution [

11,

12].

Although previous research has mainly focused on the effects of LPDs on growth performance and nitrogen balance, the systemic effects of protein restriction—particularly on meat quality, gut microbiota, and host metabolism—remain insufficiently explored [

13,

14]. LPDs can alter the composition of the intestinal microbiota, potentially enriching bacterial taxa involved in nitrogen cycling, such as

Christensenellaceae [

15]. However, the integrative impact of protein level reduction on the gut microbiota, host metabolic pathways, and muscle nutrient profiles in finishing pigs remains poorly understood.

Therefore, the present study aimed to comprehensively investigate the effects of low-protein diets on finishing pigs using multi-omics approaches. By integrating data on growth performance, 16S rRNA sequencing, serum metabolomics, and muscle composition analysis, this study seeks to elucidate how LPDs affect gut microbiota, serum metabolic pathways, and muscle fatty acid profiles, ultimately providing more sustainable strategies for swine production.

2. Materials and Methods

All procedures involving pigs were carried out at Niu Jiaowan Pig Farm Co., Ltd. (Leizhou City, Zhanjiang, Guangdong Province, China) under the management of the Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of China Agricultural University (Approval No. AW22302302-1-4).

2.1. Animals, Design and Management

A total of 180 healthy crossbred finishing pigs (Duroc × Liangguang Small Spotted; initial body weight 85.49 ± 4.90 kg) were enrolled in a 35-day trial and randomly assigned (six replicate pens per treatment, ten pigs per pen, male: female = 1:1) to one of three dietary regimens: Control (CON), receiving a standard protein diet (15.5% crude protein); Low-Protein 1 (LP1), containing 14.5% crude protein; or Low-Protein 2 (LP2), formulated with 13.5% crude protein. All diets supplied equivalent net energy, calcium, phosphorus and standardized ileal digestible amino acids (

Table 1). The barn was equipped with an intelligent environmental control system capable of regulating temperature and humidity; however, during the experimental period, the indoor temperature remained above the preset range of 20 ± 2 °C due to the high ambient temperature in summer, while the relative humidity was maintained between 60% and 75%. The house floor was a partially slatted concrete floor. Each pen (3.2 m × 4.0 m) was equipped with a stainless-steel dry–wet feeder and a nipple-type automatic drinking system, allowing pigs ad libitum access to feed and water. In addition, vaccination was carried out according to the schedule detailed in

Supplementary Table S1.

2.2. Sample Collection

Daily feed offered and refusals were recorded for each pen to compute average daily feed intake (ADFI). Body weights taken on experimental day 0 and day 35 were used to calculate average daily gain (ADG). Feed conversion ratio (FCR) was calculated as follows:

During days 33 to 35 of the experiment, fecal and feed samples (1 kg each) were collected from each pen after thoroughly cleaning the pen. Samples were collected twice daily (morning and evening), and care was taken to avoid fecal contamination. All samples were mixed thoroughly and dried in a 65 °C oven for 72 h. The dried feed and fecal samples were ground through a 1 mm sieve and held at 4 °C until analysis.

On the morning of day 35, after an overnight fast, one pig with an average body weight was selected from each replicate for blood sampling. Approximately 10 mL of blood was collected via the anterior vena cava using a sterile winged infusion set (22 G) connected to an EDTA-K2 anticoagulant tube (Shandong Ao Saite Medical Equipment, Heze, China) for hematological analysis, and another 10 mL was collected into vacuum tubes without anticoagulant for serum preparation. All blood samples were gently inverted several times immediately after collection and transported to the laboratory at 2–8 °C within 2 h. The anticoagulated blood was used for hematological determinations, while the non-anticoagulated blood was left standing for approximately 3 h at room temperature, followed by centrifugation at 3000× g for 10 min at 4 °C. The obtained serum was aliquoted into 2 mL cryotubes and stored at −80 °C until further biochemical and metabolomic analyses.

On day 36, following a 12 h fast, the same animals were transported (60–70 km/h for 1 h), allowed to rest for 4 h, then stunned electrically and slaughtered. Cecal contents were immediately collected and rapidly frozen (snap-frozen) in liquid nitrogen. Two samples of Longissimus dorsi (between the third and fourth last ribs on the left side) were excised—one kept on ice for meat-quality assays and the other frozen in liquid nitrogen before storage at −80 °C. Approximately 10 g each of liver tissue and mid-cecum chyme were collected from each pig as representative samples. About 1–2 g portions were subsampled into sterile 2 mL cryotubes, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until further analysis.

2.3. Chemical Analysis

2.3.1. Nutrient Digestibility and Fecal Nitrogen Excretion

Dry matter (DM) and crude protein (CP) in feed and feces were analyzed using Association of Official Analytical Chemists [

16] procedures; neutral detergent fiber (NDF) was determined on an ANKOM Fiber Analyzer (ANKOM Technology, Macedon, NY, USA) following Van Soest et al. [

17]; gross energy (GE) was measured by an oxygen-bomb calorimeter (Model 6400, Parr Instrument Company, Moline, IL, USA) in accordance with ISO 9831:1998 [

18]; and chromium concentrations were quantified by atomic absorption spectrophotometry (Z-5000; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

Apparent total tract digestibility (ATTD) of each nutrient was then calculated as follows:

where DC is chromium concentration in the diet, FN is nutrient concentration in feces, FC is chromium concentration in feces, and DN is nutrient concentration in the diet.

The calculation of fecal nitrogen excretion per unit of body weight gain was performed according to the method described by Pan et al. [

19], as follows:

2.3.2. Hematological, Serum Biochemical, and Serum Metabolomics Analyses

Hematological parameters were determined using an automated hematology analyzer (ADVIA® 2120i Hematology System, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc., Erlangen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The measured indicators included white blood cell count (WBC), red blood cell count (RBC), hemoglobin concentration (Hb), hematocrit (HCT), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), platelet count (PLT), red cell distribution width–standard deviation (RDW-SD), red cell distribution width–coefficient of variation (RDW-CV), and mean platelet volume (MPV).

Serum biochemical parameters were analyzed using a CX-4 automatic biochemical analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). The measured items included alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), total protein (TP), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), glucose (GLU), triglycerides (TG), and total cholesterol (TC). All analyses were performed using commercial assay kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

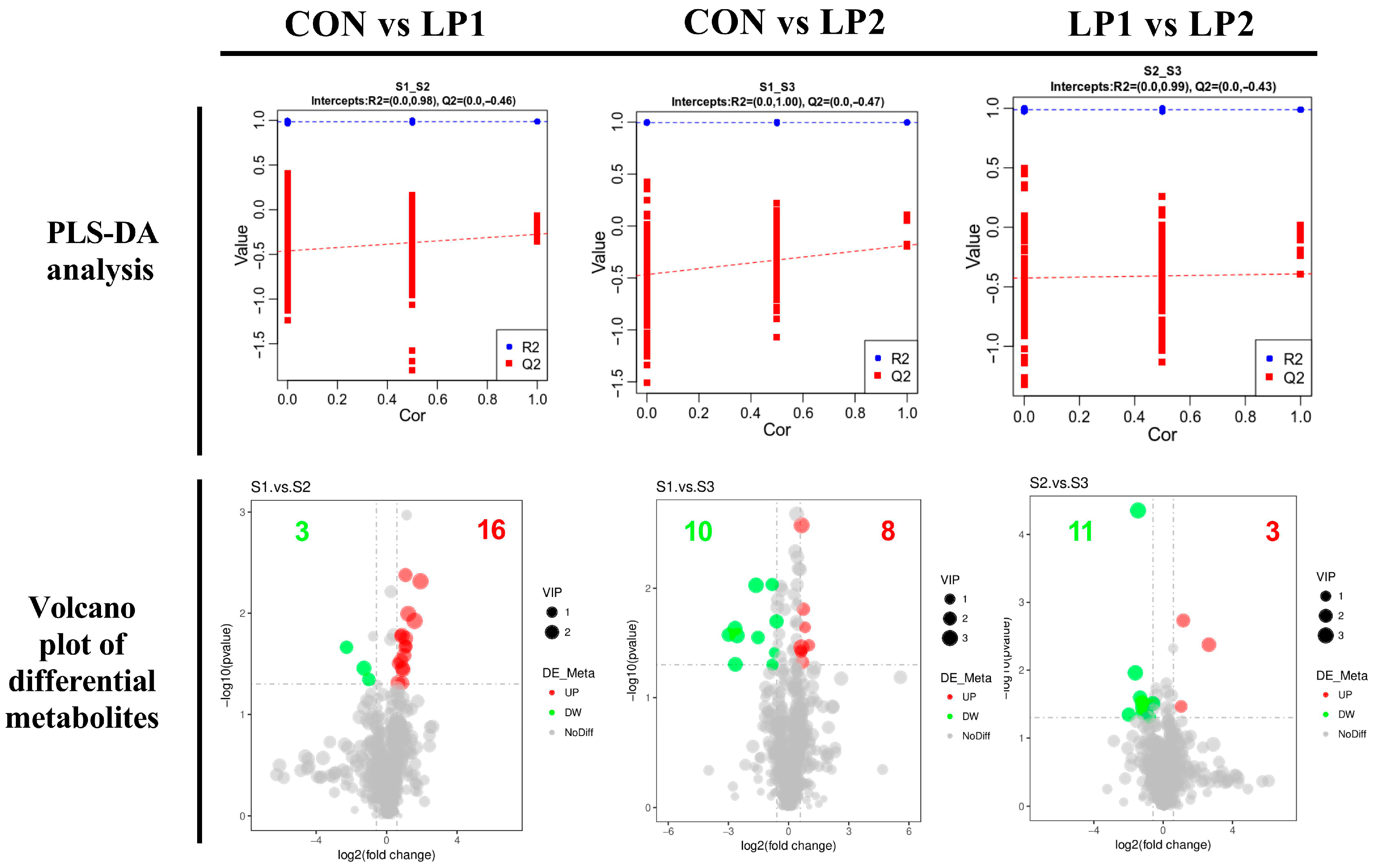

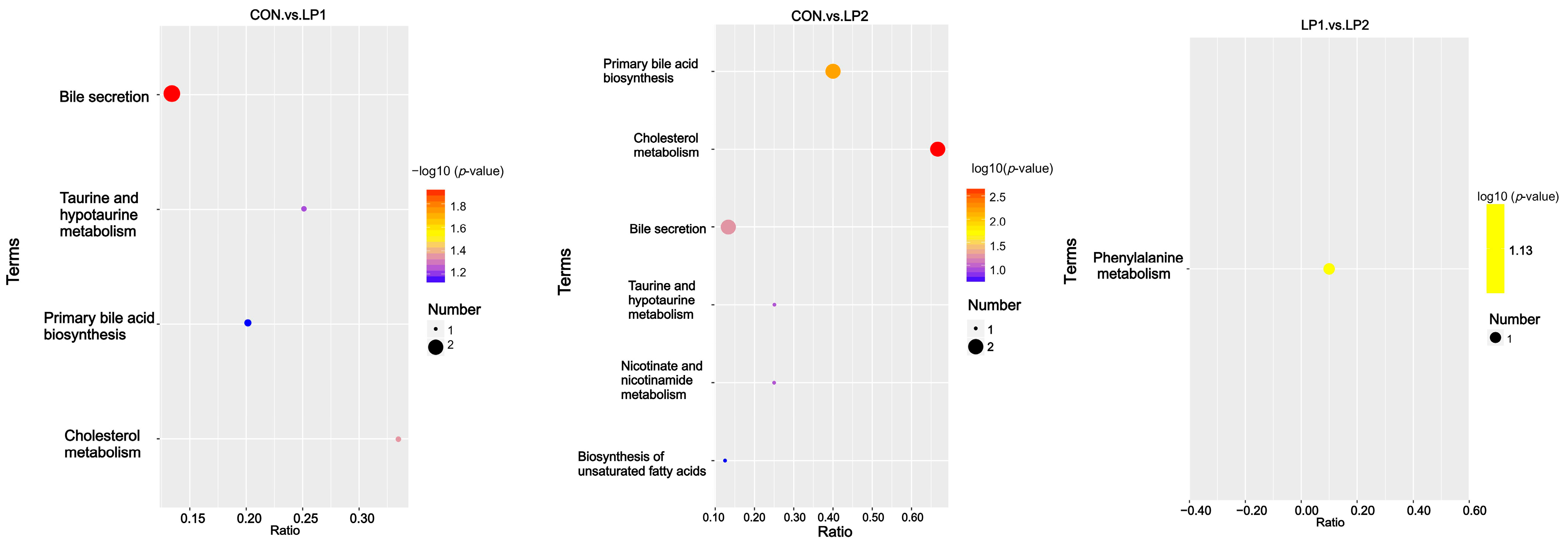

Non-targeted serum metabolomics analysis was performed according to Liu Et Al. [

20]. In brief, serum (400 μL) was mixed 1:1 with methanol: acetonitrile (

v/

v), sonicated (40 kHz, 30 min, 5 °C), then centrifuged (13,000×

g, 15 min, 4 °C). The supernatant was dried under nitrogen, reconstituted in acetonitrile: water (1:1,

v/

v), briefly sonicated, centrifuged again, and transferred to liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) vials. Metabolites were profiled on a Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA, USA) LC-MS/MS, annotated via Human Metabolome Database (HMDB), Metlin and Majorbio, and processed on the Majorbio Cloud Platform.

2.3.3. Hepatic Biochemical Analyses

Hepatic antioxidant parameters, including superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity, total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC), and malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration, were determined using commercial assay kits, whereas inflammatory and stress-related indicators, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-10 (IL-10), and heat shock protein 70 (HSP-70), were quantified using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China). Total protein concentration in the liver homogenates was determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit from the same manufacturer. All hepatic parameters were normalized to total protein content and expressed per mg or g of total protein.

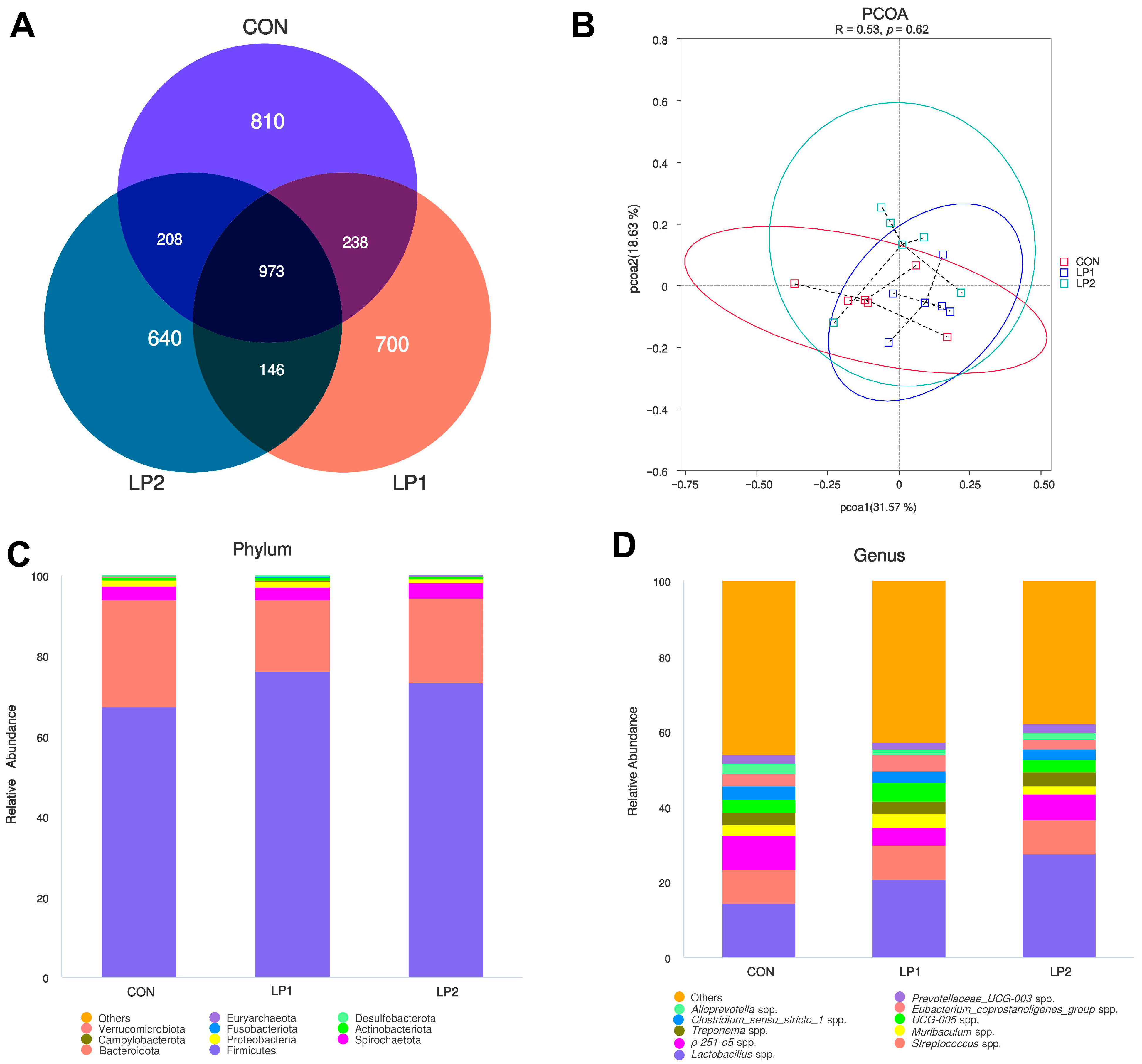

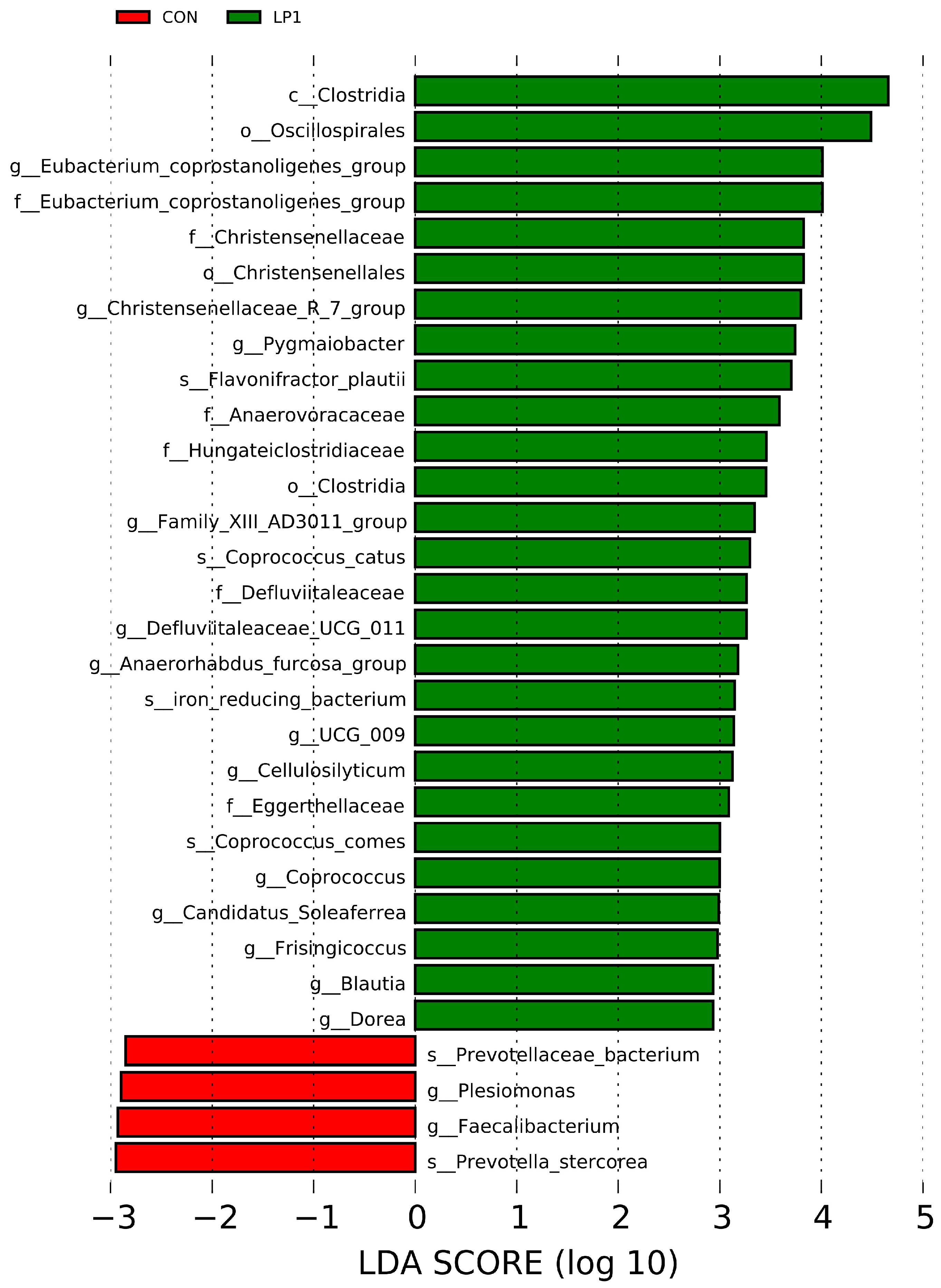

2.3.4. Cecal Microbiota Analysis

Five cecal chyme samples (one per replicate) were processed for 16S rRNA profiling at Shanghai Majorbio. Genomic DNA was extracted (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, USA) and quantified by NanoDrop. The V3–V4 region was amplified with primers 338F/806R (

Table S2), purified (AxyPrep), and measured on a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Sequencing libraries were generated and run as 300 bp paired-end reads on an Illumina HiSeq PE300 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Raw reads were quality-filtered with Trimmomatic and merged using Fast Length Adjustment of Short reads (FLASH version 1.2.11) software, then clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 97% similarity via a highly accurate method for generating OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Taxonomic assignment employed the ribosomal database project database, and relative abundances were reported as percentages.

2.3.5. Meat Quality Evaluation of Longissimus dorsi Muscle

Within 45 min post-slaughter, backfat thickness, muscle color, drip loss, pH

45min and loin eye area were assessed. Backfat was measured at the first rib, between the 6th–7th ribs and the last lumbar vertebra using a vernier caliper, and the mean of these three readings was recorded. The

Longissimus dorsi cross-section’s width and height were also measured by caliper, with muscle color determined on the loin eye region using a CR-410 colorimeter (Konica Minolta, Tokyo, Japan). Loin eye area (cm

2) was calculated as (width × height) × 0.7, and drip loss (%) was calculated as follows:

2.3.6. Amino Acid Composition of Longissimus dorsi Muscle

Freeze-dried Longissimus dorsi powder (0.1 g) was accurately weighed into ampoules, then hydrolyzed with 10 mL of 6 mol/L HCl at 110 ± 1 °C for 24 h. After cooling, the hydrolysate was transferred into a 100 mL volumetric flask, and 1 mL aliquots were evaporated to dryness at 60 °C. To remove residual acid, each dry residue was dissolved in 1 mL of distilled water and evaporated twice more. The final residue was reconstituted in 1 mL of double-distilled water, filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane, and 1 mL of filtrate was analyzed on a Hitachi L-8900 amino acid analyzer (Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Total amino acids were then quantified.

2.3.7. Fatty Acid Profiling of Longissimus dorsi Muscle

Lipids were extracted from freeze-dried muscle samples using chloroform: methanol (2:1, v/v). Fatty acid methyl esters were prepared and analyzed by gas chromatography (Agilent 6890 series, Wilmington, DE, USA). Results were expressed as mg of fatty acid per g of dry-matter muscle.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Except for microbiota and metabolomics data, all statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.3.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Each pen was considered the experimental unit. Data were tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test and for homogeneity of variances using Levene’s test before performing ANOVA. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA to compare treatment groups, followed by Duncan’s multiple range test for post hoc comparisons, with the Kruskal–Wallis rank—sum test applied when data failed parametric assumptions. Cecal microbiota differences and effect sizes were determined by LEfSe (LDA score ≥ 2.00), while serum metabolites showing FDR—adjusted p < 0.05 in one—way ANOVA were further evaluated by LDA (score ≥ 2.5) and subjected to both univariate and multivariate analyses in MetaboAnalyst 4.0 (The Metabolomics Innovation Centre, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada). Trends were noted at 0.05 < p ≤ 0.10, significant differences at p ≤ 0.05, and highly significant differences at p ≤ 0.01.

4. Discussion

Dietary optimization by partially substituting crude protein with crystalline amino acids such as lysine, tryptophan, and threonine has become a well-established nutritional approach to reduce dietary protein while maintaining performance [

21]. In our study, both LP1 and LP2 diets, when supplemented with essential amino acids, supported growth performance comparable to the control group, consistent with the results of Han et al. [

10], who observed that reducing dietary crude protein by 1–1.5% did not impair growth performance, nutrient digestibility, or meat quality in finishing pigs. By contrast, more drastic reductions without proper amino acid balancing have been reported to compromise intake and weight gain [

22]. These findings collectively highlight that adequate amino acid supplementation is the key to sustaining animal performance under reduced protein regimens. In China, indigenous pig breeds such as Meishan, Fengjing, and Minzhu are known for their slower growth rates compared to commercial breeds like Duroc. Previous studies have reported that the ADG of these local breeds is significantly lower than that of Duroc pigs [

23]. Most research on Chinese native pigs has focused on their reproductive performance and meat quality [

24], with limited studies examining their growth parameters such as ADG and ADFI. Among the few studies on the Duroc × Liangguang Small Spotted crossbred, reports from domestic Chinese journals show that their ADG ranges from 488 to 549 g/d, ADFI from 2180 to 2350 g/d, and FCR from 4.15 to 4.76 during the finishing phase. These results align closely with those of our study, where the Duroc × Liangguang Small Spotted crossbred pigs exhibited ADG values ranging from 542.09 to 559.82 g/d, ADFI from 2263.71 to 2267.33 g/d, and FCR from 4.06 to 4.19. These results indicate that this hybrid cross, even with moderate dietary protein reduction, maintains favorable growth performance, supporting the notion that protein reduction with proper amino acid supplementation does not impair growth.

Beyond growth performance, the environmental benefits of low-protein diets deserve emphasis. Finishing pigs typically display low nutrient utilization efficiency, leading to excessive nitrogen excretion and environmental pollution [

25]. Incorporating crystalline amino acids into reduced-protein diets enhances nitrogen utilization efficiency, thereby reducing nitrogen losses [

4,

5]. In the present trial, dietary protein reduction by 1–2% lowered nitrogen output per kilogram of weight gain by 9–14% without affecting apparent total tract digestibility, echoing previous reports that each 1% reduction in dietary protein reduces nitrogen excretion by 8–10% [

11,

12]. Thus, our results reinforce the environmental value of amino acid–fortified low-protein diets in reducing the ecological footprint of pig production.

Carcass traits and muscle nutrient composition further revealed threshold-dependent responses to protein reduction. LP1 pigs exhibited increased backfat thickness compared with both the control and LP2 groups, whereas no significant differences were observed in loin-eye area, drip loss, or pH values. Similar results have been reported by Morazán et al. [

26], who found that reduced dietary protein increased backfat deposition, and by Madrid et al. [

27], who suggested that decreased protein intake reduces the energy lost through protein catabolism and urinary nitrogen, thereby favoring lipid deposition. The absence of further fat accumulation in LP2 suggests that additional protein restriction may cross a metabolic threshold, limiting substrates for lipid accretion. Nutrient composition analyses of the

Longissimus dorsi provided further evidence for these threshold-dependent effects. While total fatty acid levels did not differ between the control and LP1 groups, LP2 selectively reduced several key fatty acids, including palmitic acid (C16:0), stearic acid (C18:0), and oleic acid (C18:1n9c). These findings align with Liu et al. [

28], who reported that reducing protein in Ningxiang pigs decreased the levels of C17:0, C17:1, and C18:3n3, and with Zhou et al. [

29] and Teye et al. [

30], who observed declines in saturated and unsaturated fatty acids under low-protein diets. Such changes are important because intramuscular fatty acid composition directly influences meat nutritional value and consumer preference. Similarly, the muscle amino acid profile showed that LP2-fed pigs had significantly reduced concentrations of both essential amino acids (e.g., lysine, phenylalanine, leucine) and flavor-related amino acids (e.g., glutamic acid, aspartic acid) compared with LP1. Essential amino acids are critical for protein deposition and growth [

31], while glutamic and aspartic acids contribute to umami taste and pork palatability [

32]. Comparable studies have reported minimal changes in pork amino acid composition under moderate protein restriction [

33], whereas Berrazaga et al. [

34] emphasized that protein source and amino acid balance shape muscle amino acid profiles. Together, these results suggest that moderate protein reduction (LP1) can maintain both nutritional and sensory qualities of pork, but further restriction (LP2) risks reducing the levels of amino acids central to meat quality.

Integration of microbiota and metabolomic data provides mechanistic insights into these observations. Excess dietary protein reaching the hindgut fosters proteolytic fermentation and favors pathogenic bacteria [

35], whereas reducing protein intake or improving digestibility suppresses proteolytic fermentation and enriches beneficial taxa [

36]. In the present study, the control group exhibited higher abundances of

Prevotella spp. and

Faecalibacterium spp., while LP1 enriched

Christensenellaceae and

Clostridia. These taxa have been linked with improved fiber fermentation and host lipid metabolism [

15], suggesting that moderate protein reduction selectively reshaped the gut microbial community toward functions beneficial for energy utilization. The microbial shifts coincided with serum metabolomic changes, particularly the downregulation of bile secretion and cholesterol metabolism pathways. Such alterations are consistent with Xu et al. [

7], who reported reduced bile acid synthesis and altered lipid metabolism in pigs fed long-term low-protein diets. Moreover, the metabolic reprogramming observed here coincided with differences in carcass fatness and muscle nutrient composition, supporting the notion that gut microbiota and host metabolism jointly mediate the effects of dietary protein reduction. Supporting this, Gurr et al. [

37] demonstrated that low-protein diets increased plasma triiodothyronine levels, indicating enhanced lipid metabolism, and Fuller [

38] proposed that protein restriction shifts metabolic resources from protein synthesis toward lipid storage. Thus, the combined evidence suggests that dietary protein reduction regulates a diet–microbiota–host axis, which governs lipid turnover, nitrogen utilization, and muscle nutrient deposition. In addition, considering that the mean barn temperature during the trial reached 31.36 °C, pigs in this study were exposed to heat stress conditions. Heat stress has been shown to impair intestinal integrity, alter microbial composition, and reduce feed intake and growth performance [

39]. Previous studies have reported that low-protein diets can alleviate heat stress by reducing metabolic heat production, improving nitrogen utilization efficiency, and maintaining antioxidant balance [

40,

41]. Therefore, the beneficial microbial and metabolic adaptations observed here may partly reflect the mitigating effects of low-protein diets under heat-stress conditions. Future research should further explore the interaction between dietary protein levels and heat stress responses to better understand their combined influence on intestinal health and metabolism.