Programmed Grooming after 30 Years of Study: A Review of Evidence and Future Prospects

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review of the Programmed Grooming Model

2.1. Recent Advances in the Molecular Basis of Rodent Grooming

2.2. General Predictions to Differentiate between the Models (Table 1)

| Programmed Grooming Model | Stimulus-Driven Grooming Model |

|---|---|

| Grooming is regulated by an endogenous mechanism independent of parasite bites | Grooming is regulated by exogenous peripheral stimulation from ectoparasite bites |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.3. Specific Predictions of Programmed Grooming (Table 2)

2.3.1. Body Size Principle

| Cost of ectoparasites increases with decreasing body size due to greater surface-to-volume ratios in smaller animals

|

| Cost of grooming exceeds fitness benefit for energy-limited breeding males that must prioritize vigilance for estrous females and rival males

|

| Species have evolved a species-typical baseline grooming rate that matches the intensity of ectoparasite threat in their ancestral habitat

|

| Species respond to short-term changes in parasite challenge by adjusting their grooming efforts

|

2.3.2. Vigilance Principle

2.3.3. Habitat Principle

2.3.4. Tick Challenge Principle

2.4. Predictions of the Programmed Grooming Model

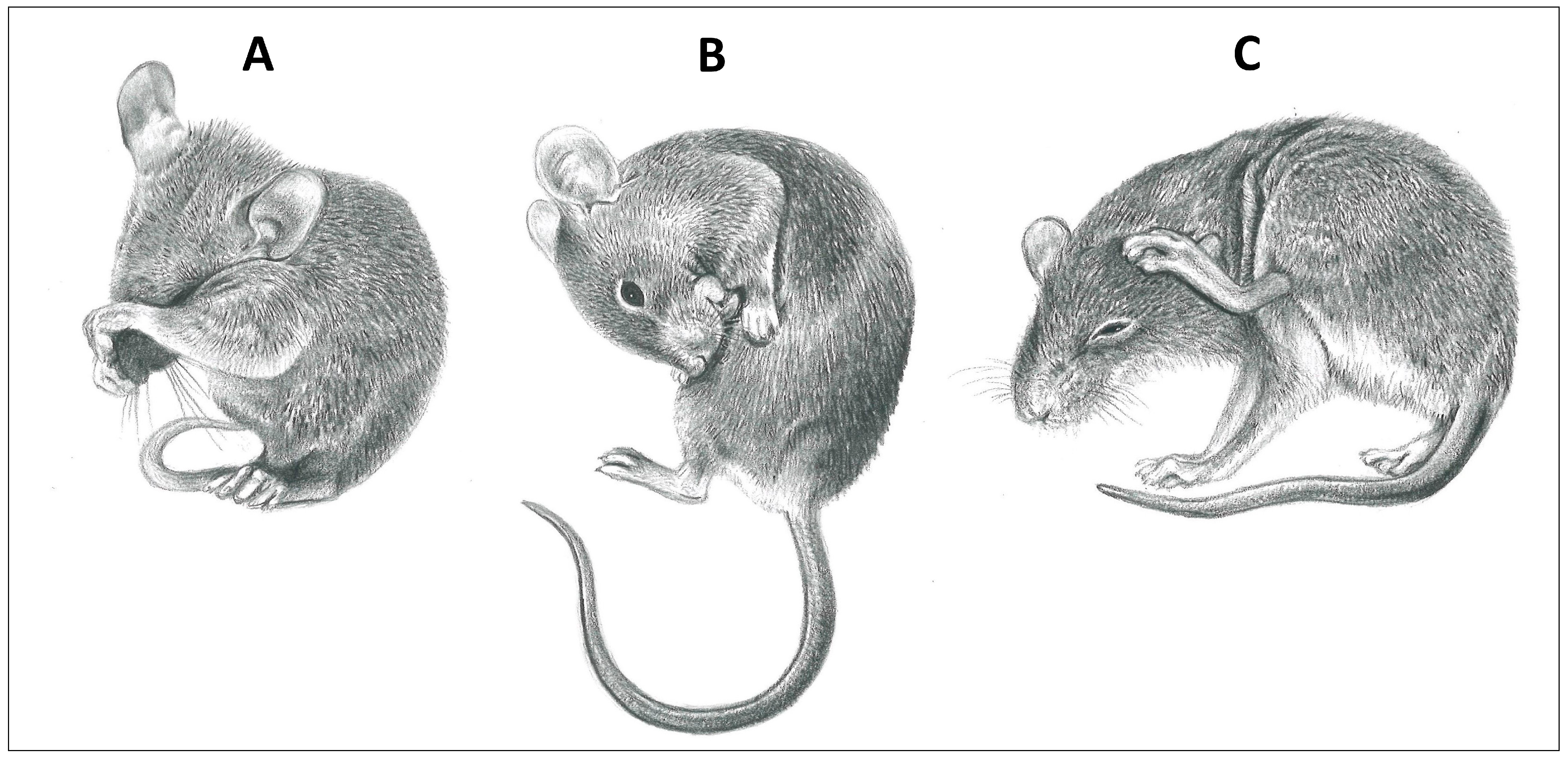

- Between species, individuals of smaller species will groom more frequently than those of larger species (interspecific body size principle). Usually, females are compared to control for intraspecific variation.

- Within a species, smaller juveniles will groom more frequently than larger adults and, for sexually dimorphic species, smaller females will groom more frequently than larger males (intraspecific body size prediction).

- Within a species, the grooming rate of actively breeding males will be lower compared with non-breeding males or adult females (vigilance prediction).

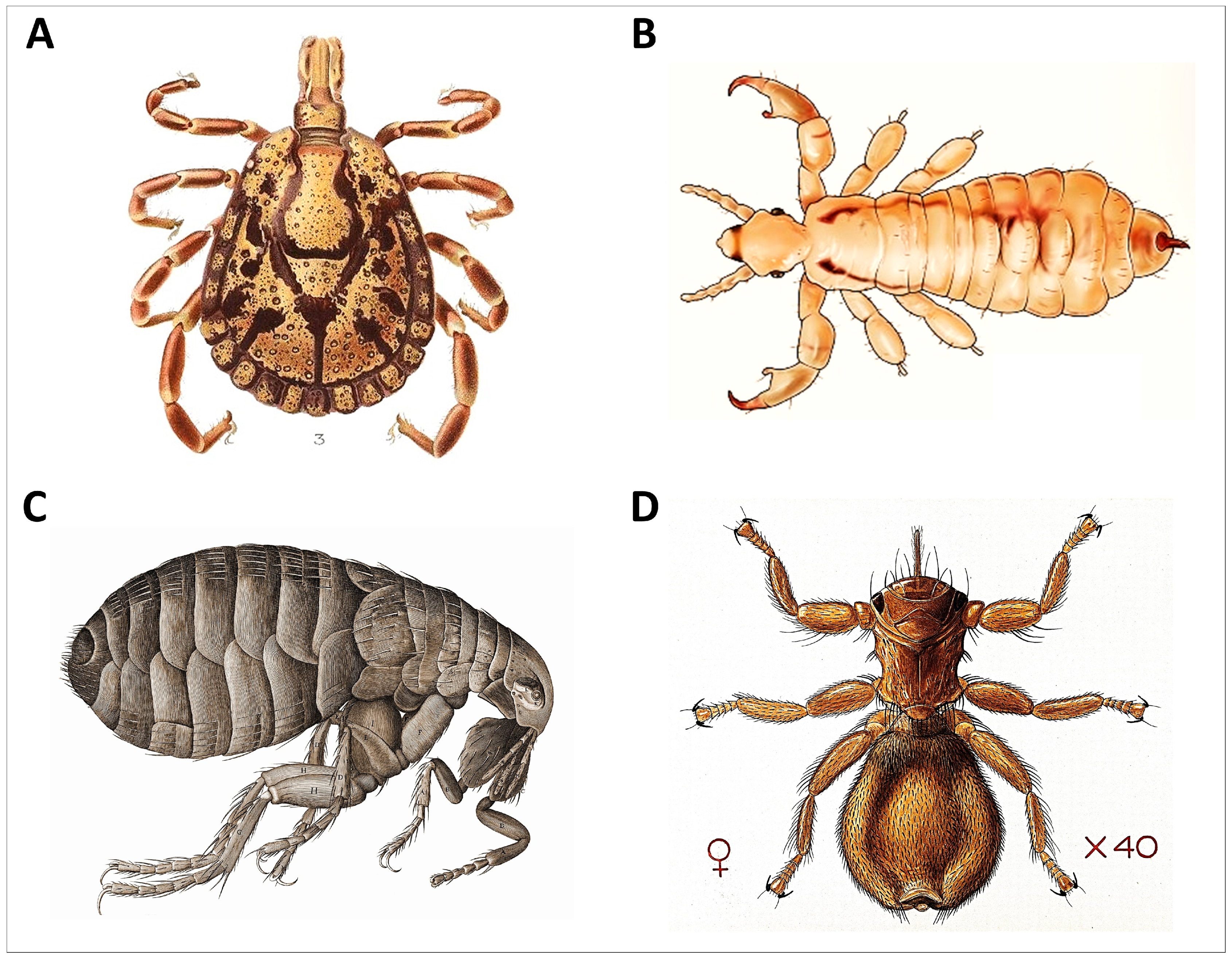

- Individuals exposed to a higher density of ectoparasite infestation will groom more than individuals exposed to lower infestation and such individuals will carry a lower ectoparasite load as a result (tick challenge principle).

- Species that are adapted to ectoparasite-dense environments will groom at a higher rate compared with species adapted to ectoparasite-sparse habitats, even in an environment with little or no ectoparasites (habitat principle).

2.5. Allogrooming

3. Results

3.1. Testing the Model Predictions

3.1.1. Hawlena et al., 2008

3.1.2. Sarasa et al., 2011

3.1.3. Heine et al., 2016

3.1.4. Blank 2023

3.1.5. Summary

3.2. Testing the Model Itself

- If individuals that groom more have fewer parasites (i.e., grooming rate is negatively correlated with parasite load or density). Note that stimulus-driven grooming predicts the opposite, that individuals with more parasites will groom more.

- If individuals maintain a baseline rate of grooming in a parasite-free or parasite-sparse environment. Even better, if individuals display the predicted differences in body size, sex, or breeding status in a parasite-free/sparse environment.

- Note that these criteria were formulated with tick parasitism in mind. Would these criteria be different when considering other parasites, such as fleas or keds?

3.2.1. Stopka and Graciasova 2001

3.2.2. Yamada and Urabe 2007

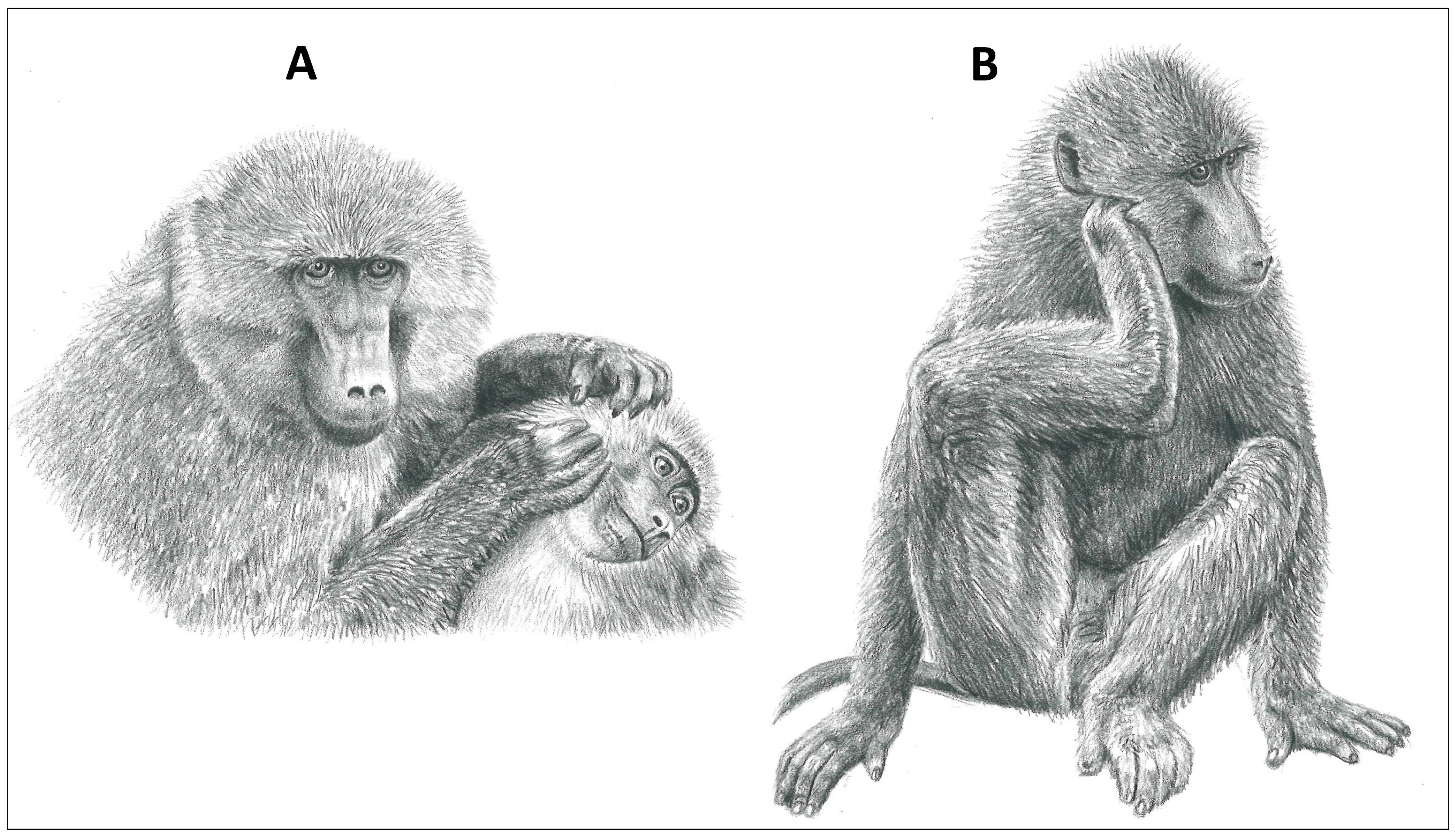

3.2.3. Akinyi et al., 2013

3.2.4. Eads et al., 2017

3.2.5. Rayner et al., 2022

4. Conclusions and a Personal Reflection

4.1. History of the Programmed Grooming Model

4.2. Conclusions

- The Hart–Mooring studies used a standardized methodology that did not vary across dozens of field investigations. However, the new studies generally employ different data collection methods, which often make it difficult or impossible (e.g., [66]) to compare studies or to interpret the results in light of the programmed grooming predictions. In my opinion, any investigation seeking to explicitly test the programmed grooming model must make every effort to use the same methods and metrics that we used, if this is possible.

- The predictions of the programmed grooming model should be tailored to the biology of the host under investigation. The original formulation of the model predictions was based on ungulate hosts, which may not be appropriate for alternative hosts. For rodents, in which altricial juveniles may have a lighter hair coat, less surface-to-volume ratio differences compared with adults, and are incapable of fully functional self-grooming, testing the body size principle by comparing the grooming rate of juveniles versus adults may not be appropriate. It might be more useful to predict that juveniles will employ more efficient grooming patterns, such as the dorsoventral sequence of grooming observed in sciurognathid rodents [37].

- Similarly, the predictions of the programmed grooming model should be tailored to the biology of the ectoparasite involved. Because the model predictions were based on tick ectoparasites, some aspects of the model may be inappropriate for alternative parasites, such as lice, fleas, or keds. Unlike ticks, which move slowly, take a long time to blood feed, feed only once, and produce only slight cutaneous irritation, fleas and keds are highly mobile, feed multiple times, and ked bites are rather painful. One might expect that the effectiveness of a programmed grooming system could be different for these ectoparasites compared with ticks and may, thus, require new predictions.

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Little, D.A. The Effect of Cattle Tick Infestation on the Growth Rate of Cattle. Aust. Vet. J. 1963, 39, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherst, R.W.; Maywald, G.F.; Kerr, J.D.; Stegeman, D.A. The Effect of Cattle Tick (Boophilus microplus) on the Growth of Bos indicus x Bos taurus Steers. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 1983, 34, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, M.; Sutherst, R.; Bourne, A. Tick (Acarina: Ixodidae) Infestations on Zebu Cattle in Northern Uganda. Bull. Entomol. Res. 1991, 81, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norval, R.A.I.; Sutherst, R.W.; Kurki, J.; Gibson, J.D.; Kerr, J.D. The Effect of the Brown Ear-tick Rhipicephalus appendiculatus on the Growth of Sanga and European Breed Cattle. Vet. Parasitol. 1988, 30, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, H.G. Suitability of Birds and Mammals as Hosts for Immature Stages of the Lone Star Tick, Amblyomma americanum (Acari, Ixodidae). J. Med. Entomol. 1981, 18, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, H.G. Suitability of White-tailed Deer, Cattle, and Goats as Hosts for the Lone Star Tick, Amblyomma americanum (Acari, Ixodidae). J. Kansas Entomol. Soc. 1988, 61, 251–257. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, B.L. Behavioral Adaptations to Pathogens and Parasites: Five Strategies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1990, 14, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckstein, R.A.; Hart, B.L. Grooming and Control of Fleas in Cats. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2000, 68, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

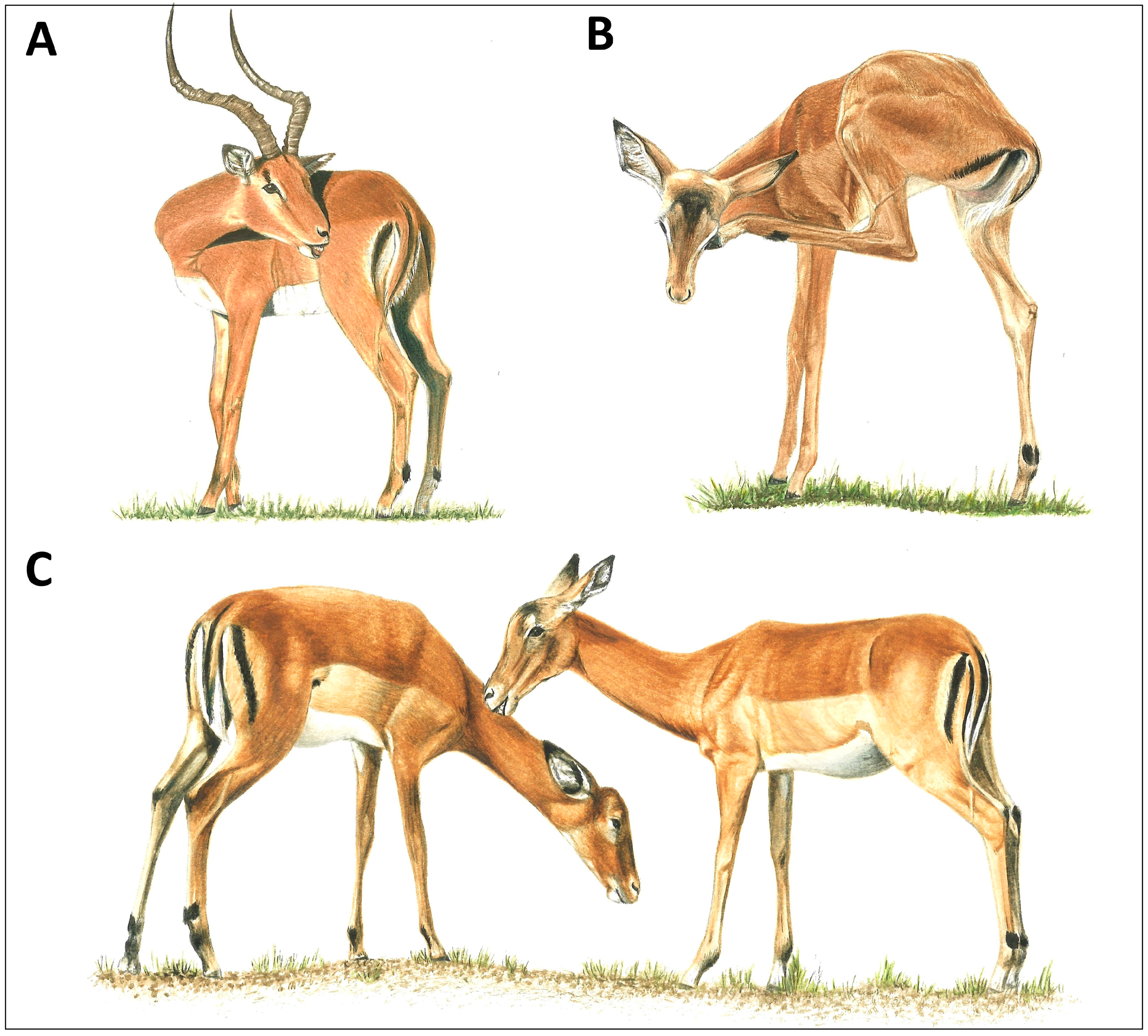

- Mooring, M.S.; McKenzie, A.A.; Hart, B.L. Grooming in Impala: Role of Oral Grooming in Removal of Ticks and Effects of Ticks in Increasing Grooming Rate. Physiol. Behav. 1996, 59, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestripieri, D. Vigilance Costs of Allogrooming in Macaque Mothers. Am. Nat. 1993, 141, 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cords, M. Predator Vigilance Cost of Allogrooming in Wild Blue Monkeys. Behaviour 1995, 132, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooring, M.S.; Hart, B.L. Costs of Allogrooming in Impala: Distraction from Vigilance. Anim. Behav. 1995, 49, 1414–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooring, M.S.; Hart, B.L. Differential Grooming Rate and Tick Load of Territorial-Male and Female Impala, Aepyceros melampus. Behav. Ecol. 1995, 6, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooring, M.S.; McKenzie, A.A.; Hart, B.L. Role of Sex and Breeding Status in Grooming and Total Tick Load of Impala. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1996, 39, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, R.C.; Epstein, A.N. Saliva Lost by Grooming: A Major Item in the Rat’s Water Economy. Behav. Biol. 1974, 11, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenzie, A.A. The Ruminant Dental Grooming Apparatus. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 1990, 99, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooring, M.S.; Samuel, W.M. Premature Loss of Winter Hair in Free-ranging Moose (Alces alces) Infested with Winter Ticks (Dermacentor albipictus) is Correlated with Grooming Rate. Can. J. Zool. 1999, 77, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, B.L.; Hart, L.A.; Mooring, M.S.; Olubayo, R. Biological Basis of Grooming Behavior in Antelope—The Body Size, Vigilance and Habitat Principles. Anim. Behav. 1992, 44, 615–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averianov, A.O.; Lopatin, A.V. High-level Systematics of Placental Mammals: Current Status of the Problem. Biol. Bull. 2014, 41, 801–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooring, M.S. The Effect of Tick Challenge on Grooming Rate by Impala. Anim. Behav. 1995, 50, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawlena, H.; Abramsky, Z.; Krasnov, B.R. Ectoparasites and Age-dependent Survival in a Desert rodent. Oecologia 2006, 148, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido, M.; Adler, V.H.; Pnini, M.; Abramsky, Z.; Krasnov, B.R.; Gutman, R.; Kronfeld-Schor, N.; Hawlena, H. Time Budget, Oxygen Consumption and Body Mass Responses to Parasites in Juvenile and Adult Wild Rodents. Parasites Vectors 2016, 9, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brain, C.; Bohrmann, R. Tick Infestation of Baboons (Papio ursinus) in the Namib Desert. J. Wildl. Dis. 1992, 28, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veríssimo, C.J.; D’Agostino, S.M.; Pessoa, F.F.; de Toledo, L.M.; de Miranda Santos, I.K.F. Length and Density of Filiform Tongue Papillae: Differences Between Tick-susceptible and Resistant Cattle May Affect Tick Loads. Parasites Vectors 2015, 8, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, A.A.; Weber, A. Loose Front Teeth: Radiological and Histological Correlation with Grooming Function in the Impala Aepyceros melampus. J. Zool. 1993, 231, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, L.L.; Rosenblatt, J.S. Changes in Self-licking During Pregnancy in the Rat. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 1967, 63, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, W.A.; Keirans, J.E.; Bell, J.F.; Clifford, C.M. Host Ectoparasite Relationships. J. Med. Entomol. 1975, 12, 143–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbern, D.L.; Gispen, W.H. Neural Mechanisms and Biological Significance of Grooming Behavior. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1988, 525, R9–R10. [Google Scholar]

- Fentress, J.C. Expressive Contexts, Fine-structure, and Central Mediation of Rodent Grooming. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1988, 525, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruijt, B.M.; Vanhooff, J.A.R.A.M.; Gispen, W.H. Ethology and Neurobiology of Grooming Behavior. Physiol. Rev. 1992, 72, 825–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riek, R. Studies on the Reactions of Animals to Infestation with Ticks. VI. Resistance of Cattle to Infestation with the Tick Boophilus microplus (Canestrini). Crop Past. Sci. 1962, 13, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willadsen, P. Immunity to Ticks. Adv. Parasitol. 1980, 18, 293–313. [Google Scholar]

- Wikel, S.K. Immunomodulation of Host Responses to Ectoparasite Infestation—An Overview. Vet. Parasitol. 1984, 14, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francischetti, I.M.; Sa-Nunes, A.; Mans, B.J.; Santos, I.M.; Ribeiro, J.M. The Role of Saliva in Tick Feeding. Front. Biosci. 2009, 14, 2051–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mooring, M.S.; Blumstein, D.T.; Stoner, C.J. The Evolution of Parasite-defence Grooming in Ungulates. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2004, 81, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, J.M.; Capecchi, M.R. Hoxb8 is Required for Normal Grooming Behavior in Mice. Neuron 2002, 33, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malange, J.; Alberts, C.C.; Oliveira, E.S.; Japyassú, H.F. The Evolution of Behavioural Systems: A Study of Grooming in Rodents. Behaviour 2013, 150, 1295–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikrin, A.N.; Moskalenko, A.M.; Mukhamadeev, R.R.; de Abreu, M.S.; Kolesnikova, T.O.; Kalueff, A.V. The Emerging Complexity of Molecular Pathways Implicated in Mouse Self-grooming Behavior. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2023, 127, 110840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalueff, A.V.; Stewart, A.M.; Song, C.; Berridge, K.C.; Graybiel, A.M.; Fentress, J.C. Neurobiology of Rodent Self-grooming and its Value for Translational Neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, N.; Capecchi, M.R. Optogenetic Stimulation of Mouse Hoxb8 Microglia in Specific Regions of the Brain induces Anxiety, Grooming, or Both. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooring, M.S.; Hart, B.L. Reciprocal Allogrooming in Wild Impala Lambs. Ethology 1997, 103, 665–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooring, M.S.; Hart, B.L. Self Grooming in Impala Mothers and Lambs: Testing the Body Size and Tick Challenge Principles. Anim. Behav. 1997, 53, 925–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooring, M.S.; Samuel, W.M. Tick-removal Grooming by Elk (Cervus elaphus): Testing the Principles of the Programmed-grooming Hypothesis. Can. J. Zool. 1998, 76, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooring, M.S.; Samuel, W.M. Tick Defense Strategies in Bison: The Role of Grooming and Hair Coat. Behaviour 1998, 135, 693–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooring, M.S.; Patton, M.L.; Reisig, D.D.; Osborne, E.R.; Kanallakan, A.L.; Aubery, S.M. Sexually Dimorphic Grooming in Bison: The Influence of Body Size, Activity Budget and Androgens. Anim. Behav. 2006, 72, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooring, M.S.; Hart, B.L.; Fitzpatrick, T.A.; Reisig, D.D.; Nishihira, T.T.; Fraser, I.C.; Benjamin, J.E. Grooming in Desert Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis mexicana) and the Ghost of Parasites Past. Behav. Ecol. 2006, 17, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, B.L.; Pryor, P.A. Developmental and Hair-coat Determinants of Grooming Behaviour in Goats and Sheep. Anim. Behav. 2004, 67, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooring, M.S.; Reisig, D.D.; Niemeyer, J.M.; Osborne, E.R. Sexually and Developmentally Dimorphic Grooming: A Comparative Survey of the Ungulata. Ethology 2002, 108, 911–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallivan, G.J.; Culverwell, J.; Girdwood, R.; Surgeoner, G.A. Ixodid ticks of Impala (Aepyceros melampus) in Swaziland: Effect of Age Class, Sex, Body Condition and Management. S. Afr. J. Zool. 1995, 30, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooring, M.S.; Gavazzi, A.J.; Hart, B.L. Effects of Castration on Grooming in Goats. Physiol. Behav. 1998, 64, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakuma, Y.; Takeuchi, Y.; Mori, Y.; Hart, B.L. Hormonal Control of Grooming Behavior in Domestic Goats. Physiol. Behav. 2003, 78, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Main, A.J.; Sprance, H.E.; Kloter, K.O.; Brown, S.E. Ixodes dammini (Acari: Ixodidae) on White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus) in Connecticut. J. Med. Entomol. 1981, 18, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, M.L.; Samuel, W. Factors Affecting Transmission of Larval Winter Ticks, Dermacentor albipictus (Packard), to Moose, Alces alces L., in Alberta, Canada. J. Wildlife Dis. 1985, 21, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnard, D.R. Aspects of the Bovine Host–Lone Star Tick Interaction Process in Forage Area. In Morphology, Physiology, and Behavioural Biology of Ticks; Sauer, J.R., Hair, J.A., Eds.; Ellis Horwood: Chichester, UK, 1986; pp. 428–444. [Google Scholar]

- Garris, G.I.; Popham, T.W.; Zimmerman, R.H. Boophilus-microplus (Acari, Ixodidae)—Oviposition, Egg Viability, and Larval Longevity in Grass and Wooded Environments of Puerto-Rico. Environ. Entomol. 1990, 19, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, J.F.; Schmidtmann, E.T. Dispersal of Blacklegged Tick (Acari: Ixodidae) Nymphs and Adults at the Woods–pasture Interface. J. Med. Entomol. 1996, 33, 554–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgson, G.M.; Flay, K.J.; Perroux, T.A.; McElligott, A.G. You Lick Me, I Like You: Understanding the Function of Allogrooming in Ungulates. Mammal Rev. 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinyi, M.Y.; Tung, J.; Jeneby, M.; Patel, N.B.; Altmann, J.; Alberts, S.C. Role of Grooming in Reducing Tick Load in Wild Baboons (Papio cynocephalus). Anim. Behav. 2013, 85, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mooring, M.S. Ontogeny of Allogrooming in Mule Deer (Odocoileus hemionus). J. Mamm. 1989, 70, 484–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopka, P.; Graciasova, R. Conditional Allogrooming in the Herb-field Mouse. Behav. Ecol. 2001, 12, 584–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, B.L.; Hart, L.A. Reciprocal Allogrooming in Impala, Aepyceros melampus. Anim. Behav. 1992, 44, 1073–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooring, M.S.; Hart, B.L. Animal Grouping for Protection from Parasites: Selfish Herd and Encounter-dilution Effects. Behaviour 1992, 123, 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooring, M.S.; Hart, B.L. Effects of Relatedness, Dominance, Age, and Association on Reciprocal Allogrooming by Captive Impala. Ethology 1993, 94, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooring, M.S.; Hart, B.L. Reciprocal Allogrooming in Dam-reared and Hand-reared Impala Fawns. Ethology 1992, 90, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawlena, H.; Bashary, D.; Abramsky, Z.; Khokhlova, I.S.; Krasnov, B.R. Programmed versus Stimulus-driven Antiparasitic Grooming in a Desert Rodent. Behav. Ecol. 2008, 19, 929–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasa, M.; Pérez, J.M.; Alasaad, S.; Serrano, E.; Soriguer, R.C.; Granados, J.E.; Fandos, P.; Joachim, J.; Gonzalez, G. Neatness Depends on Season, Age, and Sex in Iberian ibex Capra pyrenaica. Behav. Ecol. 2011, 22, 1070–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heine, K.B.; DeVries, P.J.; Penz, C.M. Parasitism and Grooming Behavior of a Natural White-tailed Deer Population in Alabama. Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 29, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, D.A. Grooming Behavior in Goitered Gazelles: The Programmed versus Stimulus-driven Hypothesis. Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 35, 62–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooring, M.S.; Samuel, W.M. The Biological Basis of Grooming in Moose: Programmed versus Stimulus-driven Grooming. Anim. Behav. 1998, 56, 1561–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckstein, R.A.; Hart, B.L. The Organization and Control of Grooming in Cats. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2000, 68, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Beauchamp, G.; Mooring, M.S. Relaxed Selection for Tick-defense Grooming in Père David’s Deer? Biol. Conserv. 2014, 178, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, N.; Kamilar, J.M.; Nunn, C.L. Host Longevity and Parasite Species Richness in Mammals. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, M.; Urabe, M. Relationship Between Grooming and Tick Threat in Sika deer Cervus nippon in habitats with Different Feeding Conditions and Tick Densities. Mammal Study 2007, 32, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eads, D.A.; Biggins, D.E.; Eads, S.L. Grooming Behaviors of Black-tailed Prairie Dogs are Influenced by Flea Parasitism, Conspecifics, and Proximity to Refuge. Ethology 2017, 123, 924–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, J.G.; Sturiale, S.L.; Bailey, N.W. The Persistence and Evolutionary Consequences of Vestigial Behaviours. Biol. Rev. 2022, 97, 1389–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooring, M.S.; Benjamin, J.E.; Harte, C.R.; Herzog, N.B. Testing the Interspecific Body Size Principle in Ungulates: The Smaller They Come, the Harder They Groom. Anim. Behav. 2000, 60, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mooring, M.S. Programmed Grooming after 30 Years of Study: A Review of Evidence and Future Prospects. Animals 2024, 14, 1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14091266

Mooring MS. Programmed Grooming after 30 Years of Study: A Review of Evidence and Future Prospects. Animals. 2024; 14(9):1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14091266

Chicago/Turabian StyleMooring, Michael S. 2024. "Programmed Grooming after 30 Years of Study: A Review of Evidence and Future Prospects" Animals 14, no. 9: 1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14091266

APA StyleMooring, M. S. (2024). Programmed Grooming after 30 Years of Study: A Review of Evidence and Future Prospects. Animals, 14(9), 1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14091266