1. Introduction

The technology of eye tracking has proven to be a powerful tool for understanding human visual perception, attention, and subsequent decision-making [

1,

2]. Whenever people look at their surroundings, they consciously or subconsciously focus on only a limited amount of the information available. This limited focus is what is commonly referred to as “visual attention” and can be measured using fixations (i.e., a prolonged pause of the eye movement on a particular element in the visual field) and saccades (i.e., the rapid movements between fixations) [

3]. Gaze behavior has been shown to generally reflect the direction of attention. It is widely assumed that it is impossible to shift the point of gaze without also shifting attention [

4].

Over the years, significant strides have been made in applying eye tracking to various domains, such as psychology, neuroscience, and human-computer interaction, to study visual attention and cognitive processes, including sports performance analysis [

5]. Eye tracking technology has been used as a diagnostic tool to analyze relevant visual search strategies or hand-eye coordination in professional sports [

6]. Wood and Wilson [

7] and Adolphe, Vickers, and Laplante [

8] employed eye tracking in structured training programs, involving video feedback of gaze behavior and on-court training. Research by Savelsbergh, van Gastel, and van Kampen [

9] demonstrated how gaze behavior and anticipation efforts may be improved through the acquisition of different gaze patterns. For instance, eye tracking has been used to analyze athletes’ visual strategies, such as how soccer players scan the field or how shooters focus on their targets. The technology provides objective data on where individuals look, for how long, and in what sequence, thereby offering insights into their attentional focus and information processing [

9,

10]. Over the years, eye tracking technology has also been used to examine the visual search strategies of sports officials and referees [

11,

12,

13]. After all, most, if not all, judges are required to take decisions in a highly pressurized environment with a wealth of information to consider in a limited amount of time [

14]. To be able to make accurate judgments, officials must be able to select and process informational cues that are most relevant to that particular situation [

12,

15].

Investigating the visual search behavior of officials involved at different levels of the sport is therefore thought to be a meaningful strategy for developing more effective decision-making capabilities [

14,

16,

17,

18]. Studies in gymnastics, for example, suggest that more experienced judges generate more fixations in total while also fixating comparatively more often on specific anatomical parts of the athlete, such as the head and arms [

19,

20,

21]. In a study involving high- and low-level ice hockey referees assessing video clips, the more experienced referees were more accurate in their decision-making, yet no differences in gaze behavior could be found between the two groups [

22]. The authors argue that visual assessment strategies differ when assessing sporting performances. At the same time, high-level referees may have developed more cognitive processes that allow them to extract relevant visual information more effectively (e.g., [

23]). As Haider and Frensch [

24] have argued in their Information Reduction hypothesis, as individuals become more skilled in a task, they process information more efficiently by focusing on relevant cues and filtering out irrelevant information. As such, it may well be the case that expert officials are able to extract critical information (visual cues) more quickly, allowing them to anticipate more effectively than novices [

9,

10,

25].

Performance in equestrian sports depends on the harmonious yet highly intricate interaction between the horse and the rider [

26]. In equestrian dressage, judges are tasked with evaluating the performance of horse-rider combinations based on a set of predefined concepts [

27,

28].

Judges must be able to provide accurate and relevant feedback on the quality of movements, the accuracy of execution, and the level of harmony between horse and rider, in line with the principles of ethical horse training [

29]. Equestrian judges generally receive extensive training based on the principles of classical dressage, commonly referred to as the Training Scale. These six interdependent and progressive criteria aim to develop a horse’s physical and mental aptitudes, preparing it step by step for the different levels of dressage: ‘Rhythm’ refers to the consistency of each pace, maintained at a steady tempo. ‘Suppleness’ reflects the fluidity of the horse’s movements across various movements and in response to the rider’s aids. The term ‘Contact’ denotes the gentle, continuous connection between the rider’s hand and the horse’s mouth. ‘Impulsion’ describes the controlled release of energy by the horse in order to move forward. ‘Straightness’ indicates the alignment of the horse’s hindquarters with its front, on straight lines as well as when bent. ‘Collection’, as the last and most advanced step of the training scale, involves the increased engagement of the hind legs and a lowering of the hindquarters, which gives the forehand a seemingly lighter appearance. Although these criteria do not directly address horse welfare, the overarching principles of the FEI mandate that the welfare of the horse is fundamental in all equestrian training and activities [

28,

30,

31].

When assessing horse-rider combinations in competition, judges are currently required to take all of these elements into account and assess them in relation to a set pattern of increasingly advanced movements [

27,

28]. However, the complexity of such judging tasks has been argued to exceed human cognitive capacity [

32,

33,

34], resulting in the development of cognitive heuristics, commonly referred to as short-cuts, in order to cope with high cognitive load, executed under time pressure [

15,

35,

36,

37]. Some of these cognitive short cuts have been shown to result in systematic errors and biases, such as nationalistic bias [

35], patriotism by proxy, home bias, reputation, and order bias [

15]. While equestrian federations do produce lengthy manuals, describing each movement in great detail, there is, as yet, a lack of specific, non-arbitrary descriptions of the most salient aspects or elements of performance, including relevant welfare parameters. As a result, there is little consensus on precisely which aspects of the horse-rider combination judges should focus on. At times, this may even lead to horse-rider combinations being awarded high scores for their performances, even though certain aspects of that performance do not align with current understandings of equine welfare [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. For example, a recent study by Kienapfel et al. [

40] investigating horse-rider combinations competing at an international Grand Prix dressage competition showed that higher judging scores were positively correlated with nasal planes held behind the vertical. Such head-neck positions were also associated with unusual oral behavior and conflict behavior. Furthermore, results also showed that riders whose horses showed more unusual oral behavior and head-neck positions behind the vertical ranked higher in the FEI world ranking. Similarly, a study by Hamilton et al. [

43] investigating conflict behaviors in horses competing in lower level dressage showed that horses with nasal planes on or behind the vertical received higher scores. While the study did not find positive correlations between higher scores and conflict behaviors, it also failed to show any negative relationships, suggesting that judges either failed to see such behavioral expressions or did not interpret them correctly. Thus, in an attempt to foster continued transparency in equestrianism and promote a continued focus on equine welfare, especially given the welfare concerns leveled at equestrianism [

44,

45,

46,

47] understanding what judges currently focus on when assessing horse-rider combinations is essential.

An earlier study by Wolframm et al. [

48] provided some initial insights into the visual search strategies of Grand Prix judges. However, as yet little is known about the visual gaze behavior of dressage judges, including which elements of the horse-rider combination dressage judges focus on. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to explore visual search behavior and attentional patterns in equestrian dressage judges at different levels and across different movements, drawing on duration and frequency of fixations.

4. Discussion

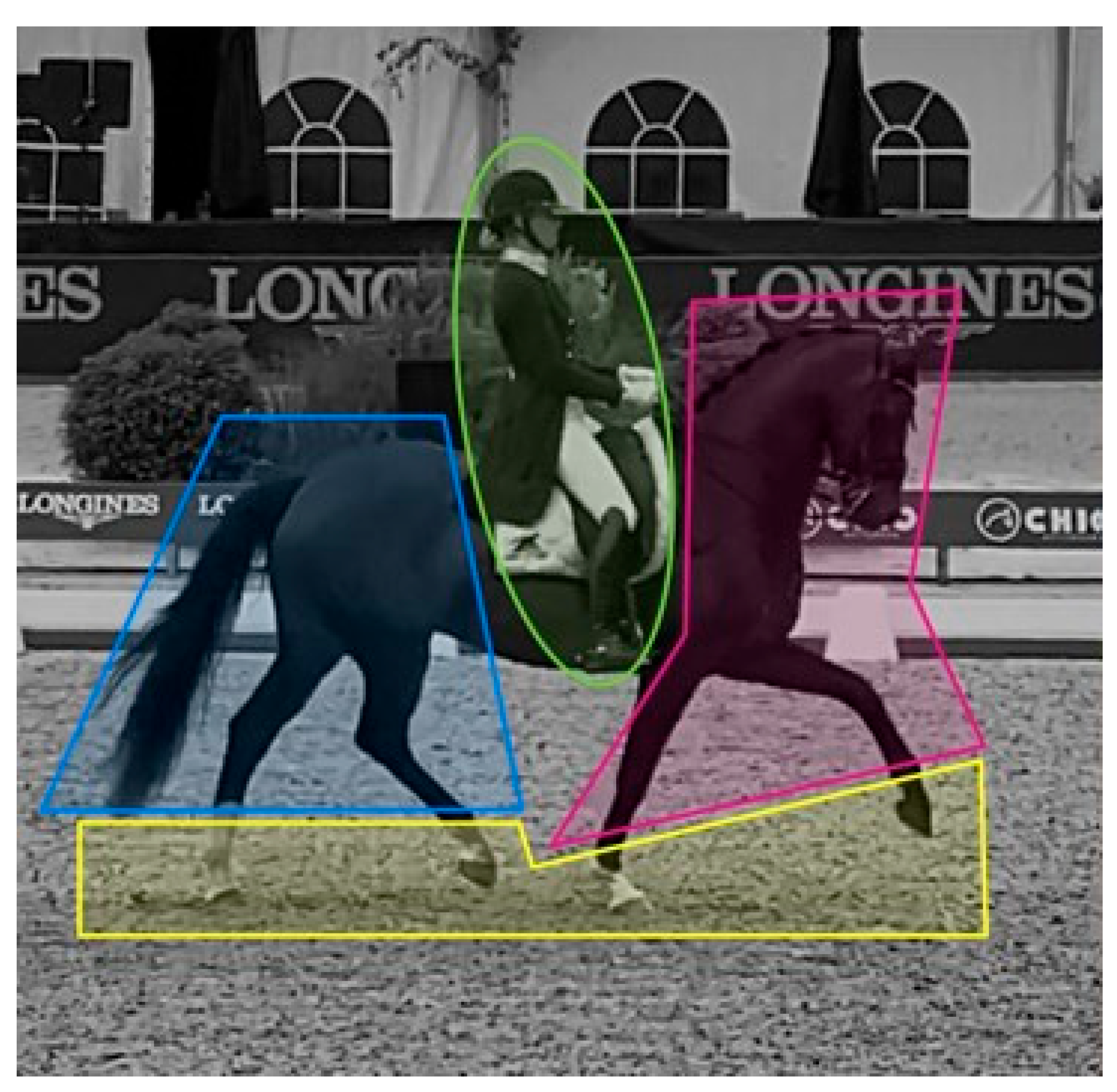

The primary aim of the study was to examine the visual search behaviors and attentional patterns of equestrian dressage judges, focusing on different movements and levels of judging expertise. Current results highlight the importance of certain anatomical areas over others and demonstrate judges’ propensity to focus on the front of the horse, irrespective of the nuanced differences across various movements.

Findings align with previous research by Wolframm et al. [

48], which demonstrated that during trot and canter movements, Grand Prix judges significantly prioritized the front of the horse over the back end of the horse or the rider. These findings are particularly interesting when considered in the context of equine training. The hindquarters of the horse are considered essential and are colloquially referred to as the “engine” of movement [

54,

55]. By teaching a horse to lower its croup, flex its hindlegs, and place them under its center of mass while pushing off actively and at the same time working into a soft contact, it will develop ‘impulsion,’ i.e., a measure of controlled yet forward-moving energy, as well as the ability to carry itself [

56,

57]. This combination of self-carriage, propulsive yet contained energy, and relaxation are considered the cornerstones of good dressage and essential to achieving both collected and extended paces [

27,

28,

54,

58,

59,

60]. As such, it may easily be assumed that judges will tend to focus on the back end of the horse to determine whether the horse is actually lowering its hindquarters and producing the required levels of energy. However, the front of the horse, particularly how it carries its head and neck, the lift through the shoulder [

54,

57,

58], and the quality of the contact [

42,

61], are likely to provide immediate and visually accessible cues of the horse’s engagement, self-carriage, and levels of relaxation [

42,

54,

56,

58].

Considering the limited time judges have to make decisions, strategic gaze patterns that rely on the most informative visual inputs while disregarding less critical data are essential [

12,

14]. Judges will have to prioritize those features that, to them, offer the most immediate and relevant visual information. Such an interpretation is in line with Haider and Frensch’s Information Reduction hypothesis [

24] and is further supported by other research highlighting the importance for judges to engage with visual cues essential for detailed processing of relevant information [

1,

2,

62]. As the findings from several studies examining equine behavioral parameters during dressage competitions seem to indicate [

40,

41,

43], conflict behaviors do not currently present sufficiently salient cues to significantly impact performance scores, possibly because they are being overshadowed by the performance parameters endorsed by current criteria [

27,

28].

Nevertheless, current findings also provide indications for a more nuanced comparison of visual search strategies between different levels of judges. In those movements in which the horse has to actively engage its hindquarters in order to achieve the level of impulsion and degree of self-carriage required to perform the movement well, namely the collected trot, collected canter, and extended canter, differences in gaze behavior between judges at the foundational compared to the advanced level became apparent. Advanced judges focused longer and more often on the horse’s feet in, respectively, the collected trot and collected canter. In extended canter, the total and average duration, as well as the number of fixations on the feet, were all greater for advanced judges compared to judges at the foundational levels of the sport. Conversely, in these three movements, foundational level judges paid comparatively more attention to the rider.

These findings tend to align with research from Bard et al. [

20] and Pizzera et al. [

19], who investigated gaze patterns in gymnastic judging. The authors found that experienced judges focused more on the gymnast’s head and arms, while novice judges paid more attention to the gymnast’s legs. The implication here is that, at an advanced level, judges are able to draw meaning from very specific areas of interest because they provide a more nuanced and subtle indication of the quality of the entire performance. Following such a line of argument, current findings would suggest that looking at, for instance, the horse’s feet is a more effective approach when assessing horse-rider performance. The Federation Equestre Internationale describes collection through the shortening of the strides with the same levels of activity, resulting in a more cadenced appearance of the gait [

27]. In the extension, the horse is required to lengthen its frame and cover more ground without the steps becoming hurried. It could therefore be argued that both for the collected and extended gaits, the feet provide essential clues on how to assess the quality of the movements. As has been argued by Spitz et al. [

63], highly advanced officials develop more elaborate knowledge structures, allowing them to extract more detailed information from very specific aspects of athletic performances and be able to predict how subsequent performance might unfold [

63,

64]. Advanced dressage judges could be argued to have developed more refined assessment strategies to judge horse-rider combinations. It should be borne in mind, though, that these knowledge structures will have developed over the past few years and be primarily based on the judging principles established by the FEI and national governing bodies [

28,

65]. Behavioral parameters indicative of a horse’s welfare state rather than performance, such as head-neck positions [

39,

40,

42], excessive oral behavior [

40], or tail swishing [

38,

40], do not, at present, feature in those judging guidelines. It stands to reason, therefore, that welfare parameters are not (yet) considered sufficiently pertinent to affect gaze behavior or subsequent judging decisions.

In equestrian sports, the level of horse-rider performance depends on two athletes, the rider and the horse. At the lower levels of the sport, the rider or the horse (or both) are merely at the beginning of their journey to develop the necessary physical (and mental) aptitude to perform in dressage. Horse-rider combinations performing at the higher levels of the sport are required to demonstrate a more sophisticated level of training. It might therefore be argued that differences in gaze behavior between advanced and foundational level judges are due to the task-specific demands required of them when judging at their usual level. At an advanced level, judges are used to seeing and assessing horse-rider combinations capable of showing degrees of collection. As a result, judges may focus more on the details that are indicative of the horse’s ability to perform those higher-level movements, such as the placement of the horse’s feet, in order to gauge the quality of collection and extensions. At the foundational level, however, judges need to pay more attention to the rider, as, at that level, riders are still developing either their own skill set or that of their horse. As such, the way they interact with their horse through their seat, legs, and hands becomes more important to evaluate. Differences in gaze behavior might therefore not merely be a reflection of a lack of proficiency but might, in fact, be indicative of different evaluation criteria for advanced compared to foundational levels. Findings from Kienapfel et al. [

42] might provide additional evidence. The authors demonstrated that a head-neck position behind the vertical was penalized at lower levels of dressage but not at higher levels. As findings from the current study demonstrated, lower level judges tend to focus more on the rider. As a result, they might be more prone to seeing the rider using inappropriate, heavy-handed aids that effectively pull the horse’s head behind the vertical. The lower scores given by the lower level judges in Kienapfel’s [

42] study might therefore be in reference to poorer riding skills, while at the same time penalizing inappropriate head-neck positions. Advanced judges, on the other hand, tend to focus significantly less on the rider, paying more attention to cues that are primarily performance-oriented, rather than indicative of welfare.

Interestingly though, current findings show no significant difference in how advanced and foundational level judges assess the walk. On average, judges focused twice as often on the front of the horse, with the average duration of fixations being as long on the front as on the feet. The rider and the back end of the horse received comparatively little attention. The walk is a gait without a suspension phase, characterized by four separate, equally spaced hoof placements. The horse must also be fully relaxed, accepting the bit without hesitation or resistance. As the walk has no suspension phase, generating the propulsive energy that can subsequently be contained and guided through a soft contact is not possible. In fact, too much or untimely interference from the rider, through the hands, legs, or an unbalanced seat, is likely to disturb the precarious rhythm of the walk and the soft, steady contact with the hand. Not surprisingly, therefore, the walk is generally considered the most challenging gait to ride well [

66,

67]. Judges’ fixation patterns on the front of the horse, followed by the feet, seem to indicate that these anatomical areas do indeed provide the most salient cues for judges to assess performances, regardless of level of experience [

19,

20,

63]. By assessing the front of the horse, judges are able to assess aspects relating to relaxation and acceptance of the contact, while fixations on the feet allow judges to determine aspects of the regularity of the walk.

Lastly, the effect of Horse-Rider Combination was less consistent across gaits. Judges focused more on Horse-Rider Combination 2 in Collected Trot and Horse-Rider Combination 1 in Extended Canter, indicating variability in visual strategies based on perceived performance or characteristics of the combinations. Additional research is required to gain a more thorough understanding of which specific elements in performance cause more or less intensive gaze patterns.

Taken together, current findings provide a first indication of which areas of the horse-rider combination provide judges with the most relevant information when assessing dressage performance. What is more, the current study also demonstrates that judges do, in fact, focus on a limited number of highly relevant areas of interest. However, these areas of interest tend to differ for certain movements and between judges at different levels of the sport. Recent studies highlight the necessity of not only focusing on gaze behavior but also on interpreting the visual information gathered [

68]. This dual focus has been identified as the “missing link” in elevating the effectiveness of judging [

14]. particularly relevant in the context of dressage. Given that undesirable head-neck positions and expressions of conflict behavior in dressage horses have been shown to be inadequately reflected in the dressage scores given [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43] it seems more important than ever to determine how judges interpret what they see. Future research should explore how assessment strategies of judges could be enhanced by opening up the discussion on precisely which aspects of the equine training scale and relevant welfare parameters, judges are assessing when focusing on specific parts of horses and riders. Providing immediate visual feedback and allowing judges to subsequently elucidate their decision-making processes might help to clarify what is meant by different training principles and how to assess them accurately, even when under time constraints. Such developments might also go some way towards lowering the cognitive load of the judging task and mitigating some of the more pronounced biases seen in dressage judging [

15,

35,

36]. Expanding this research to include other equestrian disciplines might also offer broader insights into the application of eye-tracking technology in sports performance analysis.

While this study provides considerable insights into the visual strategies of dressage judges, it is important to note the context in which these findings were generated. The number of participants, although sufficient to detect significant patterns in gaze behavior, was limited. While mitigated by the richness of the data collected from each participant, future studies should aim to include more participants, ideally also at the highest level of the sport, in order to be able to compare visual search patterns effectively.

As the judges involved in this study were not currently qualified to judge at the Grand Prix level, it was decided not to include the scores given in the analysis. In the future, combining dressage scores with visual search behavior would provide additional insights into how gaze patterns are related to perceptions of quality.

Lastly, the current study used a screen-based system to assess visual search behavior. While such a system makes it possible to accurately compare gaze behavior between individuals, it may not always replicate exactly the visual search pattern as it would in real life [

5]. Future studies should therefore focus on including dynamic eye tracking systems, which allow for the recording of visual attention in real-life settings.