Exploring and Developing the Questions Used to Measure the Human–Dog Bond: New and Existing Themes

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review of Current HAI and HDB Assessment Tool Questions (Part I)

2.2. Identifying Novel HDB Themes for Future HDB Questionnaires (Part II)

2.2.1. Participant Recruitment

2.2.2. Interview Process

2.2.3. Thematic Analysis

2.2.4. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Review of Current HAI and HDB Assessment Tool Questions (Part I)

3.2. Identifying Novel HDB Themes for Future HDB Questionnaires (Part II)

3.2.1. Affirmation of HDB from the Dog (Theme 1)

Excitement (Theme 1 Subtheme)

“When I come home from work, he gets what we call the crazies and basically that means it’s just a crazy five-minute period where he’s just like “mum’s home! I’m so excited!” he’s just running around the house, then we have a lil’ tug of war and everything. And I’m just like… it just makes me so happy!”(Guardian of a newly adopted dog)

“He was still massively bonded to his previous owner. His previous owner came to visit us about 18 months after he came to us, just kind of to say, “hi and how’s he doing?” and [Dog] went absolutely berserk when he arrived! He was so excited! I mean, literally did laps, did zoomies [sic], around the garden, you know, he was just so excited to see him!”(Current dog’s owner describing the dog being reunited with their old owner)

“He is very over the top. Yeah, no you almost have to kind of actively discourage the over enthusiasm when he walks in or when you get home.”(Guardian in a single-dog household)

“We always have a whole re-greeting dynamic even if one’s just been away for 10 min.”(Guardian to a multiple-dog household)

“So, at first when we were at home with him, he would sit in his crate, he didn’t really care about being near to us, and so that was part of the reason I thought maybe he’s doesn’t like [us], maybe he’s not happy?”(Guardian of a newly adopted dog)

“One evening he just jumped up on the couch and sat between us and we were like ‘Woah, he’s done it! he’s done it—he’s happy!’”(Guardian in a single-dog household)

Proximity (Theme 1 Subtheme)

“Some of them have been very tactile, where the dog has come to me for lots of fuss. And I’ve also been able to, like, they trust me to touch them pretty much anywhere… …whereas some of them have been more relationships of, for instance, just being nearby, so it’s more of just a companionship rather than a full-on physical relationship.”(Guardian of multiple dogs)

“She [the dog] was quite standoffish in her behaviour, in that she didn’t seek physical contact with you very, very often, or not to start with anyway, she does more now, but at the start she was very self-contained and did her own thing, and would actively at times, she’d sit with you in the room for a little while.”(Guardian of an assistance dog)

“He’ll go and lie by himself up the stairs or at the end of the couch beside you… … He would sometimes come up sit with me, but other times go and sit by himself.”(Guardian of an older dog in a multi-dog household)

Affection (Theme 1 Subtheme)

“I know everyone says dogs hate hugs, which is rubbish when it comes to [dog’s name], because [dog’s name] will wrap his arms and legs around you... … [dog’s name] sort of pulls you into him.”(Guardian discussing the differences between the dogs in their household)

“…and in the mornings, he likes to loll[sic] on me, he likes a cuddle.”(Guardian describing their daily routine with their dog)

“Some dogs enjoy that tactile contact, and when it’s a new person she’ll enjoy it with you for a few moments, whereas I could probably go on [with tactile contact] for minutes and minutes at a time with her, with her cuddling with me on the sofa and [me] stroking her.”(Guardian in a multiple dog household)

“I think I am more snuggly with my boys, and they are more snuggly with me, than the bitches are.”(Guardian in a multiple dog household)

“I think with [dog’s name] it’s probably kind of late in the evening when she’s got into a comfortable spot. If she’s close to you, and she’s kind of in a spot where she will request, you know, that you stroke her head in a certain way, and be very specific about what she wants and she literally will just kind of cuddle in, and just relax completely, and just as long as you keep doing what she wants you to do then she’s totally happy, and that’s lovely from my point of view in terms of going, you know, feel like she’s relaxing and content where she is, and knowing she’s comfortable.”(Guardian of a rehomed dog)

Recall (Theme 1 Subtheme)

“When she eats cat poo! ..... I don’t like her very much (laughs). No, I don’t think so. I think, her recall’s really bad, so when she doesn’t come back, that makes me more frustrated rather than worried because she just acting like an idiot.”(Guardian of an older dog)

“I would say he’s one of the most difficult cockers I’ve ever had to date, or worked with to date, and I would say that includes other people’s cockers. One minute he’s there and then the next he’s out and off! Hence the reason he has his own hashtag!”(Guardian of a multiple-dog household, who also breeds dogs)

“When walking the dog and a herd of runners ran by and that frightened the dog and the dog panicked and ran off. She behaved in a manner unbecoming of her you know, she freaked out and it took me a while to recover her, for her to come back to me, so I’d lost, I lost the bond in that instance.”(Male guardian of a single dog)

“Walks he always wanted to be near you, around you, he would always come back from other dogs.”(Guardian of a single dog)

Interviewer: “And when he’s out, does he retain a bond with you, or does he have any behaviours that indicate that?”

Participant: “He always loops, I mean they go far and wide pointers, they just disappear into the undergrowth and out of sight but [Dog] does specifically loop round every few minutes to check in. He’s not the pointer that kind of disappears over the horizon completely. So, he literally does come [back] and he will literally come running back to you with eye contact kind of like going “I’m here, I’m here. Are you okay? Ok right, I’m off again.” “Yeah he will look directly at you.”(Guardian of a multiple-dog household)

“Yeah. I actually learned a lot from him because he was very much the dog, you know, if you were out walking and you had him off lead, I’d call to him he’d come straight back to me, I’d pop him on the lead and someone’s off lead dog would be coming bounding up and I’d be going “Please put your dog on a lead!” and the person’s going “but he’s friendly” and I’d be going “but mine isn’t!”(Guardian of a multiple-dog household)

“In return, I expect him to, yeah, I mean, be fairly well behaved, umm, which but that’s through training and obviously I can’t expect him to be well behaved without him being trained but I mean he does all that anyway, he’s still young and he likes to play but he is generally well behaved—very well behaved actually I’d say. And when he’s out, he’s no trouble at all, he comes back when he’s called, he’s a pleasure to have as a dog actually.”(Co-guardian to a single dog)

“Well, I don’t think it is any one behaviour. I like it when he comes when I tell him to, and he likes to play with me, and I like to play with him, and I can see he’s happy because he wags his tail, and he’s happiest of all when I give him food, so it’s all aspects really, it’s his demur [sic].”(Co-guardian to a single dog)

“I think the thing I don’t like, or don’t like the idea of, is if people think I beat him [in response to the dog not coming back when called]. I’d hate to go into a park, and I call him, and he sort of like puts his head down for some reason, which he could do, and people think “oh look at that poor dog.”(Male guardian of a single dog)

“I’m not horrible to my dogs, but you must have, for their safety, you need certain boundaries or certain stringent things that are in place because their safety is important. So, if it means that I’m going to shout, somebody might interpret that as “oh you’re being a bit mean”, but I don’t want that dog going in somewhere unsafe.”(Guardian of multiple dogs)

3.2.2. Understanding of Dogs’ Preferences, Likes, and Dislikes (Theme 2)

“The two boys, I think they get as much out of physical contact and being with me as I do, and [Dog] is a classic example in that he will work much more for physical contact and praise than treats, and I train with treats, I use treats, BUT he’s definitely not a foodie orientated dog. No, he loves you—basically just give him a big physical fuss.”(Guardian to multiple dogs)

“Sometimes you can get dogs where they’re so they can provide reinforcement to themselves from the environment, and from so many other things, that potentially they don’t pay us [humans] [any attention] in [that] they are not too in tune with the owner, or the owner doesn’t necessarily play a really pivotal role in [their] development, or welfare. Do you see what I mean? Like they [guardians] feed them, and the dog knows that, but they [the dog] [would] also potentially just as happily go off with somebody else. It’s not necessarily a really unique bond in that sense.”(Dog guardian who also works with dogs)

“I remember one dog would scare her a lot so my bond would become more supportive. An example might be thunder or fireworks when then I became another role of protector.”(Guardian of an assistance dog)

“We didn’t live right next to the main road, but it was just off our road and up another one and it was there. And it was connecting between two cities, so it was quite busy and a lot of like farm trucks and stuff going past, and I was like we’ll have to do lots of desensitisation and counter conditioning to noisy trucks—didn’t bat an eyelid and there’s lots of buses as well. Doesn’t like cars splashing through puddles though; startles at the noise, of like any sort of noise like the splash of a puddle, or when a bird suddenly takes off from a bush and it’s that kind of like “spshhhh” noise, but not bangs and not claps. It is very specific, like, a specific kind of “spshhh” kind of noise.”(Guardian of a rehomed dog)

“He had been an outdoor [dog] when we got him, we realised quite quickly that he preferred to have access to the garden as much as possible. And we did, we actually gave him a kennel in a reasonably sized garden, so we actually had a kennel in the garden and we just basically kind of let him move around.”(Guardian of a rehomed older dog)

“I think one of the reasons I don’t particularly like staying away from home is because lots of hotels and Airbnb’s are really strict about not having the dog on the bed. Which she [the dog] doesn’t like and I really look forward to getting home and having a cuddle with [Dog] in the morning [on the bed] with a cup of tea.”(Guardian of an assistance dog)

“You know he’s always been like that and that’s about the only thing about him. I think, why do you do that? and I don’t know. And I don’t think I’ll ever know coz he can’t tell me.”(Guardian of an assistance dog)

“[Dog 1] has had her own different tricky areas, which has taught me so many things, but it’s not taught me to decipher them, just like, “oh, how do I cope with this? So, what do I need to do to work with that”, you know, if I brought [Dog 2] into a new house she’d settle and lie down quite easily. [Dog 1] would to an extent, but I know I could leave [Dog 2], whereas [Dog 1] would be like, “I can’t be left”. So, there is certain scenarios that [Dog 1] needs a bit more work on, she’s reliant on me because she doesn’t like being left.”(Guardian of an assistance dog)

“It’s a bit like a mum-child relationship, she definitely gets angry with me, well not angry just stroppy, but at the same time if she’s feeling poorly, or wants something, I’m the first person she comes to.”(Guardian of a single dog)

“I think [Dog] gets angry with me sometimes—oh she does get cross! She definitely gets cross. If we go somewhere, she doesn’t want to be or something, she will absolutely tell me and she’ll strop about it afterwards.”

“I think she would be very specific about who she engages with and she doesn’t engage with so she would decide whether she wants to be with you or attached to you. And you’ve got to, well we’ve learnt, or we have figured out that you have to kind of respect her choices or ways and just let her, let her kind of direct things to make her comfortable. So, she could be anybody’s as long as they were prepared to respect that. I don’t think she could cope with a house full of children for example, no way. And as we know that she’s worried about men she actively avoids them. Now, with my husband, she’s as cuddly with him as she is with me but that’s taken five years to kind of learn.”(Female owner of an older rehomed dog)

“I am conscious people have said to me “oh you shouldn’t allow that” and I’m like “why? that’s their dynamic”. Now I don’t believe they’re a pack. There is definitely a movable dynamic in our house as to, you know, who goes where, who’s allowed to sleep where, who has what toy and that kind of thing, and I allow them that”(Female owner of multiple dogs)

“I think what dogs like is rules and they want to know what they are allowed to do and what they’re not allowed to do.”(Guardian of an assistance dog)

“I think he expects sometimes, he will expect me to tell him off. Like if he picks up my shoe—and he likes to show off right—If he picks up my shoe, he knows if he sees me he’ll drop it because he knows I’m going to tell him off… …Whereas if [female owner] was to walk into the room and he’s got my shoe, and she says “stop it” he’ll sort of run around, probably doing a round of the room you see, but once he sees me he’ll drop it, and he lays down as if to say “I’ve done something wrong, I shouldn’t of done that”. So, I’m just generally harder with him [than the female owner], you know, because I want him to be a well-behaved dog.”(Guardian of a young companion dog)

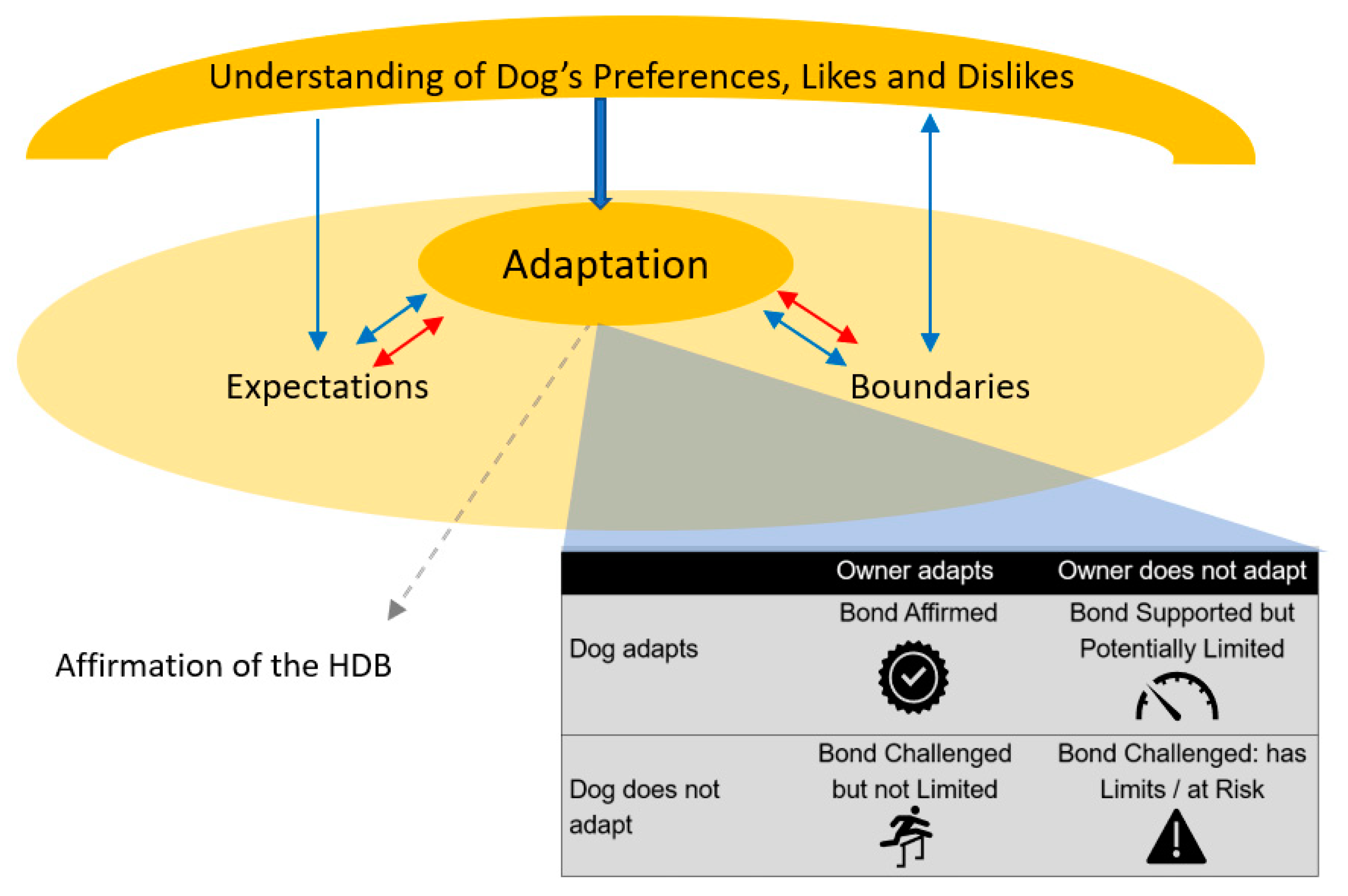

3.2.3. Adaptations of Dog and Human to the Relationship and an Evolution of the HDB (Theme 3)

“I think I just put some of the rules out of the window—with the assistance dog charity’s permission as well—and she was allowed on the bed and we didn’t worry about her pooing in a specific place and then we started to really bond, and we’ve [had] a really good bond since.”

Expectations (Theme 3 Subtheme)

“I mean, I guess collies and German shepherds are traditionally kind of bonded dogs but again, I don’t know whether that was a breed related thing or whether that was just because of his background and the way he’d been kind of raised.”(Guardian of an older rehomed dog)

“[many guardians believe that] this is brand new, but I should be Einsteining[sic] it by the end of this training session, which we know is not the case because they are individuals. And actually, it is understanding that we need to do a lot of work to buy the dog into what we’re doing, but then we can fade out the use of any tangible rewards and reinforcers if needs be.”(Dog guardian who also works with dogs)

“I think when we first got her, he [the partner] was very much hoping that she [the dog] would be if you like “his” dog, as historically quite a few [of our dogs] have kind of gravitated to me, mainly because they had more time with me because of our working pattern. So originally, I think he was anticipating, or hoping, that she would be his dog, more than my dog, but actually as it turned out, she was very, very, wary of us both—but him particularly—just being a man, so it did take him longer, him and her longer, to kind of figure each other out and decide what they like and what they don’t like, but now I would say she’s fully equally bonded with both of us, just in slightly different ways.”(Guardian of a rehomed dog)

“[Some days I think] “I’m going to let you rest, let you be a dog, let’s go for a walk”. And I don’t need to do any more with [her] or don’t want to do anything today. And actually, it’s probably made [our]—in terms of a working relationship—I’ve always had a really good, strong working relationship with [dogs] but probably the working relationship with [the dog] is even stronger [now] because when it does happen, it’s probably not as repetitive, as boring, or the pressures not [there].”(Guardian of an agility dog)

“I would say that the one [bond] they had with my partner were very affectionate and they were quite happy to chill out with him. I would say that with my dog walker… …they tend to get a lot more excitable when she comes in the house. Rather than just “oh your home hiya”, they’re like “OH MY GOD! A walk!” And it’s kind of the same with my mum, when she comes over to visit, she’s really bad for feeding them treats—no matter how often I ask her not too! If mum’s there, they’ll sit at her feet. It’s a learned behaviour but they expect it so they’re a lot more excitable…”(Guardian of a rehomed dog who also works with dogs)

Participant: “We used to walk him every day, got on really well with him, he got really excited bouncing back in his kennel. We were working on doing a grooming programme with him because he had really bad matts in his ears, but he wasn’t great at handling, so we had weeks and weeks of giving him cuddles, introducing him to the type of scissors we were going to use, making the noise around his head, and then when it came to actually touching him with the scissors—not to cut, just to touch—the minute I touched his ears with the scissors he turned, ran at me, growling, barking, growling at me, and obviously I put the scissors away and everything calmed down. But after that I’d probably say for about a week, he wasn’t as excited to see me anymore, he walked to the back of the kennel when I came towards the kennel to get him out. We did get that bond back, but I would say that he was a lot more worried about me being around him because he thought I might have the scissors again.”

Interviewer: “That’s really interesting, and quite unusual circumstances so an interesting example. Do you think it took you longer afterwards to build that bond back up with him?”

Participant: “yes definitely, he would do a lot of body language, like, he would kind of give me side-eye… …so it did take him a long time to realise I wasn’t going to do it again but to trust me again I would say.”

Interviewer: “What behaviours did he show when you got that trust back?”

Participant: “He was more excitable and waggy in his kennel, excitable when I came in, he stopped showing me side-eye… a lot more relaxed.”(Guardian of multiple dogs who worked with dogs too)

Boundaries (Theme 3 Subtheme)

Interviewer: “so almost because she needs that little bit of extra understanding? And you have that, do you think that makes you feel closer?”

Participant: “definitely you almost have to have all eyes on her in certain scenarios… …not everyone could be her owner… …I think she would be a tricky dog. For some people in those scenarios, especially taking her to the vet, because of her pain she will react… …But, you know, it doesn’t faze me, and I know that the pain is there, but I try and make [it] as pain free as possible with her.”(Guardian in a multiple-dog household)

“[Dog] has had her own different tricky areas and in there as well which has taught me so many things, but it’s not taught me to decipher them, just like, oh, how do I cope with this?”(Guardian of an assistance dog)

“I think what dogs like is rules and they want to know what they are allowed to do and what they’re not allowed to do, and so my partner moved in, and he didn’t want the dog to sleep on the bed with us. Fair enough it’s not a massive bed there’s not a load of room so suddenly the rule has changed for [dog] and she doesn’t get that, and she’s struggling as to why she now needs to sleep on the floor in her bed and not in my bed and I think that was the big problem, and so I had to compromise with my partner I said you know because you know he didn’t want the dog on the bed full stop. And I had to work with him to change that, you know not to change him but to say It’s actually really important for [dog] that she’s allowed on the bed sometimes and so every morning now if I’m not working [partner] leaves and [dog] gets on the bed and we have a cuddle—and that’s a really important part of our week.”(Guardian of a single dog)

“[Dog] would not like unknown dogs around him so that meant in the house sometimes we had, not issues, because with his own group he was fine. But as [the dog] got older, basically when I first got [other dog] I couldn’t have [other dog] and [first dog] in the house together… …I had to do lots of management.”(Guardian of a multi-dog household)

4. Discussion

4.1. HDB Affirmation

4.2. Understanding of Dogs’ Preferences, Likes, and Dislikes

4.3. Adaptation in the HDB

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Savolainen, P.; Zhang, Y.P.; Luo, J.; Lundeberg, J.; Leitner, T. Genetic evidence for an East Asian origin of domestic dogs. Science 2002, 298, 1610–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss; Basic Books; OKS Print: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Purdue University College of Veterinary Medicine. Center for the Human-Animal Bond. What Is the Human-Animal Bond? Available online: https://vet.purdue.edu/chab/about.php (accessed on 21 January 2019).

- American Veterinary Medical Association. Human-Animal Bond. Available online: https://www.avma.org/one-health/human-animal-bond (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- Society for Companion Animal Studies. Human-Animal Bond. Available online: http://www.scas.org.uk/human-animal-bond/ (accessed on 17 April 2020).

- Russow, L.-M. Ethical Implications of the Human-Animal Bond in the Laboratory. ILAR 2002, 43, 33–37. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ilarjournal/article/43/1/33/84617 (accessed on 17 April 2020).

- Johnson, T.P.; Garrity, T.F.; Stallones, L. Psychometric Evaluation of the Lexington Attachment to Pets Scale (LAPS). Anthrozoös 1992, 5, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.C.; Netting, F.E. The Status of Instrument Development in the Human–Animal Interaction Field. Anthrozoös 2012, 25 (Suppl. 1), s11–s55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, A. Considering the “Dog” in Dog–Human Interaction. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 642821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, E.; Bennett, P.C.; McGreevy, P.D. Current perspectives on attachment and bonding in the dog–human dyad. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2015, 8, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barker, S.B.; Wolen, A.R. The benefits of human–companion animal interaction: A review. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2008, 35, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowan, A.N.; Beck, A.M. The Health Benefits of Human-Animal Interactions. Anthrozoös 1994, 7, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samet, L.; Vaterlaws-Whiteside, H.; Upjohn, M.; Casey, R. Status of Instrument Development in the Field of Human-Animal Interactions & Bonds: Ten Years On. Soc. Anim. 2021; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crabtree, B.F.; Miller, W.L. Doing Qualitative Research, 2nd ed.; Sage: Southend Oaks, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog, H. Women Dominate Research on the Human-Animal Bond, Psychology Today. Available online: https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/animals-and-us/202105/women-dominate-research-the-human-animal-bond (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- Diesel, G.; Brodbelt, D.; Pfeiffer, D.U. Reliability of assessment of dogs’ behavioural responses by staff working at a welfare charity in the UK. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 115, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, C.; Jarvis, S.; McGreevy, P.D.; Heath, S.; Church, D.B.; Brodbelt, D.C.; O’Neill, D.G. Mortality resulting from undesirable behaviours in dogs aged under three years attending primary-care veterinary practices in England. Anim. Welf. 2018, 27, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gácsi, M.; Maros, K.; Sernkvist, S.; Faragó, T.; Miklósi, A. Human analogue safe haven effect of the owner: Behavioural and heart rate response to stressful social stimuli in dogs. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Horn, L.; Huber, L.; Range, F. The importance of the secure base effect for domestic dogs—Evidence from a manipulative problem-solving task. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barcelos, A.M.; Kargas, N.; Maltby, J.; Hall, S.; Mills, D.S. A framework for understanding how activities associated with dog ownership relate to human well-being. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, R.; Custance, D. A counterbalanced version of Ainsworth’s Strange Situation Procedure reveals secure-base effects in dog-human relationships. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 109, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehn, T.; McGowan, R.T.S.; Keeling, L.J. Evaluating the Strange Situation Procedure (SSP) to Assess the Bond between Dogs and Humans. PLoS ONE. 2013, 8, e56938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topál, J.; Miklósi, Á.; Csányi, V.; Dóka, A. Attachment Behavior in Dogs (Canis familiaris): A New Application of Ainsworth’s (1969) Strange Situation Test. J. Comp. Psychol. 1998, 112, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Solomon, J.; Beetz, A.; Schöberl, I.; Gee, N.; Kotrschal, K. Attachment security in companion dogs: Adaptation of Ainsworth’s strange situation and classification procedures to dogs and their human caregivers. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2018, 21, 389–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bräuer, J. I do not understand but I care. Interact. Stud. Soc. Behav. Commun. Biol. Artif. Syst. 2015, 16, 341–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, A.C.V.; Fuchs, D.; Morello, G.M.; Pastur, S.; De Sousa, L.; Olsson, I.A.S. Does training method matter? Evidence for the negative impact of aversive-based methods on companion dog welfare. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0225023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira de Castro, A.C.; Barrett, J.; de Sousa, L.; Olsson, I.A.S. Carrots versus sticks: The relationship between training methods and dog-owner attachment. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2019, 219, 104831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa, M.; Kikusui, T.; Onaka, T.; Ohta, M. Dog’s gaze at its owner increases owner’s urinary oxytocin during social interaction. Horm. Behav. 2009, 55, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, T.R.; Lyons, J.B.; Tetrick, M.A.; Accortt, E.E. Multidimensional quality of life and human-animal bond measures for companion dogs. J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 2010, 5, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratkin, J.L. Examining the Relationship between Puppy Raisers and Guide Dogs in Training; University of Texas Libraries: Austin, TX, USA, 2015; Available online: https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/33291 (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- Lindsay, S. Handbook of Applied Dog Behavior and Training, Adaptation and Learning; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; Available online: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=zZcMxLKpM0UC (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Bowlby, J. A Secure Base Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 1988; pp. 137–157. [Google Scholar]

- Herwijnen, I.R.; van Borg, J.A.M.; van der Naguib, M.; Beerda, B. The existence of parenting styles in the owner-dog relationship. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dotson, M.J.; Hyatt, E.M. Understanding dog-human companionship. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eretová, P.; Chaloupková, H.; Hefferová, M.; Jozífková, E. Can children of different ages recognize dog communication signals in different situations? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pongrácz, P.; Molnár, C.; Dóka, A.; Miklósi, Á. Do children understand man’s best friend? Classification of dog barks by pre-adolescents and adults. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2011, 135, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tami, G.; Gallagher, A. Description of the behaviour of domestic dog (Canis familiaris) by experienced and inexperienced people. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 120, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Keuster, T.; Jung, H. Aggression toward familiar people and animals. In BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Behavioural Medicine, 2nd ed.; Horwitz, D., Mills, D., Eds.; BSAVA: London, UK, 2017; pp. 182–210. [Google Scholar]

- Munch, K.L.; Wapstra, E.; Thomas, S.; Fisher, M.; Sinn, D.L. What are we measuring? Novices agree amongst themselves (but not always with experts) in their assessment of dog behaviour. Ethology 2019, 125, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plous, S. McGraw-Hill Series in Social Psychology. In The Psychology of Judgment and Decision Making; Mcgraw-Hill Book Company: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman, A.J.; Hardin, C.D. Differential use of the availability heuristic in social judgment. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1997, 23, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duranton, C. Local synchrony as a tool to estimate affiliation in dogs. J. Vet. Behav. 2020, 36, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duranton, C.; Bedossa, T.; Gaunet, F. Interspecific behavioural synchronization: Dogs exhibit locomotor synchrony with humans. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Duranton, C.; Bedossa, T.; Gaunet, F. The perception of dogs’ behavioural synchronization with their owners depends partially on expertise in behaviour. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 199, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duranton, C.; Gaunet, F. Behavioural synchronization from an ethological perspective: Overview of its adaptive value. Adapt Behav. 2016, 24, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumley, P.R.; Gorski, J.D.; Saxton, A.M.; Granger, B.P.; New, J.C. Companion Animal Attachment and Military Transfer. Anthrozoös 1993, 6, 258–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafer, R.; Lago, D.; Wamboldt, P.; Harrington, F. The Pet Relationship Scale: Replication of Psychometric Properties in Random Samples and Association With Attitudes Toward Wild Animals. Anthrozoös 1992, 5, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, J.; Ireland, J.L. The development and factor structure of a questionnaire measure of the strength of attachment to pet dogs. Anthrozoös 2011, 24, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikusui, T.; Nagasawa, M.; Nomoto, K.; Kuse-Arata, S.; Mogi, K. Endocrine Regulations in Human–Dog Coexistence through Domestication. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 30, 793–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöberl, I.; Beetz, A.; Solomon, J.; Wedl, M.; Gee, N.; Kotrschal, K. Social factors influencing cortisol modulation in dogs during a strange situation procedure. J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 2016, 11, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Staats, S.; Miller, D.; Carnot, M.J.; Rada, K.; Turnes, J. The Miller-Rada commitment to pets scale. Anthrozoös 1996, 9, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallones, L.; Johnson, T.P.; Garrity, T.F.; Marx, M.B. Quality of attachment to companion animals among US adults 21 to 64 years of age. Anthrozoös 1990, 3, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melson, G.F. Pet Attachment Scale (PAS)—Revised and PAS parent report (1988). In Assessing the Human–Animal Bond: A Compendium of Actual Measures; Anderson, D.C., Ed.; Purdue University Press: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2007; pp. 58–80. [Google Scholar]

- Templer, D.I.; Salter, C.A.; Dickey, S.; Baldwin, R.; Veleber, D.M. The construction of a pet attitude scale. Psychol. Rec. 1981, 31, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poresky, R.H.; Hendrix, C.; Mosier, J.E.; Samuelson, M.L. The companion animal bonding scale: Internal reliability and construct validity. Psychol. Rep. 1987, 60, 743–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angle, R.L.; Blumentritt, T.; Swank, P. Pet Bonding Scale, PBS (1993). In Assessing the Human–Animal Bond: A Compendium of Actual Measures; Anderson, D.C., Ed.; Purdue University Press: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2007; pp. 104–106. [Google Scholar]

- Holcomb, R.; Williams, R.C.; Richards, P.S. The elements of attachment: Relationship maintenance and intimacy. J. Delta Soc. 1985, 2, 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J.H.; Juhasz, A.M. The preadolescent/pet friendship bond. Anthrozoös 1995, 8, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, L.; Madresh, E.A. Romantic partners and four-legged friends: An extension of attachment theory to relationships with pets. Anthrozoös 2008, 21, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigg, J.; Smith, B.; Bennett, P.; Thompson, K. Developing a scale to understand willingness to sacrifice personal safety for companion animals: The Pet-Owner Risk Propensity Scale (PORPS). Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 21, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, F.; Bennett, P.C.; Coleman, G.J. Development of the Monash Dog Owner Relationship Scale (MDORS). Anthrozoös 2006, 19, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cromer, L.D.; Barlow, M.R. Factors and Convergent Validity of The Pet Attachment and Life Impact Scale (PALS). Hum.-Anim. Interact. Bull. 2013, 1, 34–56. [Google Scholar]

- Zasloff, R.L. Measuring attachment to companion animals: A dog is not a cat is not a bird. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1996, 47, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geller, K. Quantifying the Power of Pets: The Development of an Assessment Device to Measure the Attachment Between Humans and Companion Animals; Virginia Tech: Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2005; Available online: https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/handle/10919/27274 (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- Wilson, C.C.; Barker, S.B. Challenges in Designing Human-Animal Interaction Research. Am. Behav. Sci. 2003, 47, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilcha-Mano, S.; Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. An attachment perspective on human–pet relationships: Conceptualization and assessment of pet attachment orientations. J. Res. Pers. 2011, 45, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marston, L.C.; Bennett, P.C. Reforging the bond—Towards successful canine adoption. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2003, 83, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | HAB Definition |

|---|---|

| Purdue University College of Veterinary Medicine (2019) | “A dynamic relationship between people and animals in that each influences the psychological and physiological state of the other.” [3] |

| American Veterinary Medical Association (2019) | “A mutually beneficial and dynamic relationship between people and animals that is influenced by behaviours essential to the health and wellbeing of both.” [4] |

| Society for Companion Animal Studies (2019) | “A close relationship between people and animals.” [5] |

| Russow (2002) | “A reciprocal and persistent relationship between a human and an animal and their interactions must support the wellbeing of both parties.” [6] |

| Johnson et al. (1992) | “An emotional attachment between an owner and their pet.” [7] |

| Criteria | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Objectively worded and not ambiguous, nor containing conjecture, nor anthropomorphism. |

| 2 | Applicable to an HDB, i.e., not referring to an HAI with another species in a way that could never be used for a dog (e.g., “My bird often speaks to me when I enter the room”). |

| 3 | Applicable to a relationship beyond an HAI (e.g., bond, attachment). |

| 4 | Applicable to all types of dog guardian but aimed at adults (18+ years). |

| 5 | Original-duplicated questions were removed (where identifiable the original source was retained). |

| 6 | Compatible with the Dogs Trust 1 ethos to promote high welfare standards in all aspects of dog care (e.g., questions mentioning hitting a dog were vetoed so as not to promote or normalise this behaviour as an acceptable response). |

| Characteristics of Participants | Number of Interviews Ascertained |

|---|---|

| Rehomed dog/s | 6 |

| Dog/s owned since puppy | 5 |

| Multiple dog home | 5 |

| Multiple person home | 11 |

| Children in home | 2 |

| Owned dog/s > 5 years | 5 |

| Dog has a role other than being a pet (e.g., assistance) | 3 |

| Works with dogs | 4 |

| Identifies as male | 3 |

| LS = 18 Content Categories | HVW = 21 Content Categories |

|---|---|

| Affection Closeness (proximity) Attitudes towards animals & pets Care External Representation Confidante Communication Relationship Emotional Support Feelings towards pet Feelings towards self with pet Neutral or negative experiences Miscellaneous Play Positive experiences and emotions Purpose/meaning/responsibility Separation Support/dependence | One-to-one engagement Attitudes/feelings towards animals Changes in dog behaviour Companionship value Daily Care Dog Investment Emotional benefit Emotional dependence Feelings towards a specific pet Food General affection/physical affection Proximity dog Proximity human Responsible dog ownership/guardianship Self-improvement General Concern for Welfare Lifestyle adaption Miscellaneous Social benefits Training/obedience Understanding |

| Broad Themes | Question Content Categories | Human- or Dog-Centric |

|---|---|---|

| One-to-one engagement (11%) | One-to-one engagement (HVW) Proximity human (HVW) General affection/physical affection (HVW) Affection (LS) Play (LS) | Human and Dog |

| Attitudes towards animals and pets (1%) | Attitudes/feelings towards animals (HVW) Attitudes towards animals & pets (LS) | Human |

| Care & welfare (8%) | Care (LS) Daily Care (HVW) Food (HVW) General Concern for Welfare (HWV) Separation (LS) | Human and Dog |

| Companionship value/Emotional benefit (48%) | Confidante (LS) Companionship value (HVW) Communication (LS) Emotional Support/benefit/dependence (LS/HVW) Feelings towards pet (LS) Feelings towards self with pet (LS) Positive experiences and emotions (LS) Neutral or negative experiences (LS) Support /dependence (LS) Purpose/meaning/responsibility (LS) Social benefits (HVW) Self-improvement (HVW) | Human |

| Dog investment (8%) | Proximity dog (HVW) Closeness (proximity) (LS) Dog Investment (HVW) Changes in dog behaviour (HVW) | Dog |

| Feelings towards “that” (specific) pet (2%) | Feelings towards a specific pet (HVW) Relationship (LS) External Representation (LS) Understanding (HVW) | Human |

| Lifestyle adaption/Time Investment (13%) | Lifestyle adaption (HVW) Neutral or negative experiences (LS) Positive experiences and emotions (LS) | Human |

| Miscellaneous (5%) | Misc. (LS/HWV) | Misc. |

| Ownership/Guardianship (2%) | Responsible dog ownership/guardianship (LS) | Human |

| Training/obedience (2%) | Training/obedience (HVW) | Human and Dog |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Samet, L.E.; Vaterlaws-Whiteside, H.; Harvey, N.D.; Upjohn, M.M.; Casey, R.A. Exploring and Developing the Questions Used to Measure the Human–Dog Bond: New and Existing Themes. Animals 2022, 12, 805. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12070805

Samet LE, Vaterlaws-Whiteside H, Harvey ND, Upjohn MM, Casey RA. Exploring and Developing the Questions Used to Measure the Human–Dog Bond: New and Existing Themes. Animals. 2022; 12(7):805. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12070805

Chicago/Turabian StyleSamet, Lauren E., Helen Vaterlaws-Whiteside, Naomi D. Harvey, Melissa M. Upjohn, and Rachel A. Casey. 2022. "Exploring and Developing the Questions Used to Measure the Human–Dog Bond: New and Existing Themes" Animals 12, no. 7: 805. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12070805

APA StyleSamet, L. E., Vaterlaws-Whiteside, H., Harvey, N. D., Upjohn, M. M., & Casey, R. A. (2022). Exploring and Developing the Questions Used to Measure the Human–Dog Bond: New and Existing Themes. Animals, 12(7), 805. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12070805