Humans and Goats: Improving Knowledge for a Better Relationship

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

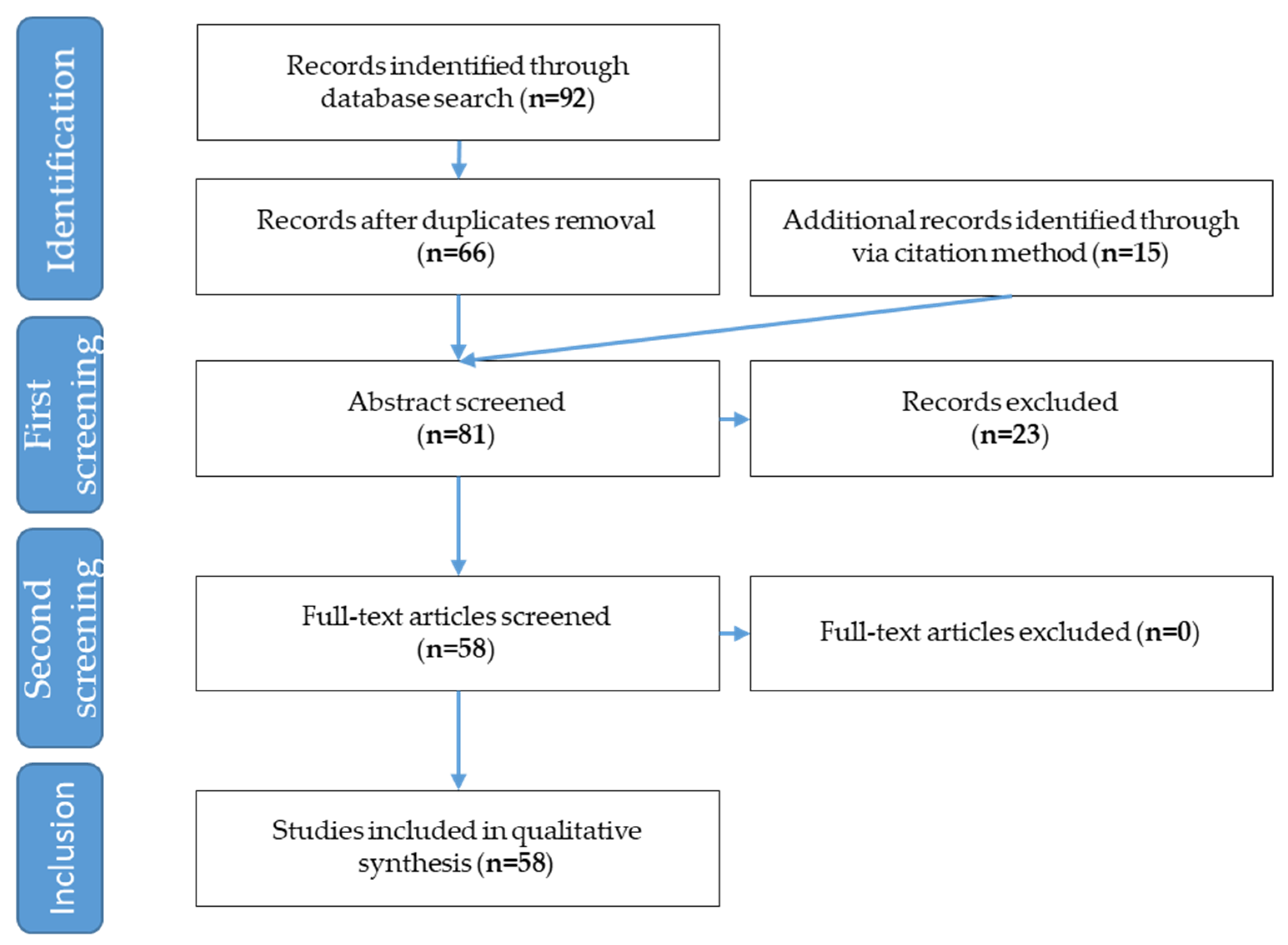

2. Materials and Methods

- (1)

- how do humans and goats communicate?

- (2)

- which are the factors affecting human–goat relationship?

- (3)

- how can we measure the quality of human–goat relationship?

3. How Can Humans and Goats Communicate?

3.1. Olfactory Communication

3.2. Visual Communication

3.3. Acoustic Communication

3.4. Tactile Communication

3.5. Gustative Communication

4. Factors Affecting Human–Goat Relationship

4.1. Environmental Factors

4.2. Individual Traits

4.3. Human Perspective

5. How Can We Assess the Quality of Human–Goat Relationship?

5.1. Behavioural Tests

5.2. Other Behavioural and Physiological Indicators

5.3. Attitudinal Questionnaires

6. Conclusions: Improving the Human–Goat Relationship

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rault, J.L.; Waiblinger, S.; Boivin, X.; Hemsworth, P. The Power of a Positive Human–Animal Relationship for Animal Welfare. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 590867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waiblinger, S.; Boivin, X.; Pedersen, V.; Tosi, M.V.; Janczak, A.M.; Visser, E.K.; Jones, R.B. Assessing the human-animal relationship in farmed species: A critical review. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2006, 101, 185–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estep, D.; Hetts, S. Interactions, relationships and bonds: The conceptual basis for scientist-animal relations. In The Inevitable Bond-Examining Scientist-Animal Interactions; Davis, H., Balfou, A., Eds.; CAB International: Cambridge, UK, 1992; pp. 6–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hemsworth, P.H.; Price, E.O.; Borgwardt, R. Behavioural responses of domestic pigs and cattle to human kind novel stimuli. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1996, 50, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybarczyk, P.; Koba, Y.; Rushen, J.; Tanida, H.; De Passillé, A.M. Can cows discriminate people by their faces? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2001, 74, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knolle, F.; Goncalves, R.P.; Jennifer Morton, A. Sheep recognize familiar and unfamiliar human faces from two-dimensional images. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2017, 4, 171228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawroth, C.; Albuquerque, N.; Savalli, C.; Single, M.S.; McElligott, A.G. Goats prefer positive human emotional facial expressions. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 180491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemsworth, P.H.; Coleman, G.J. Human–Livestock Interactions: The Stockperson and the Productivity of Intensively Farmed Animals; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hediger, H. Mensch und Tier im Zoo; Albert-Müller: Rüschlikon-Zürich, Switzerland, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Keeling, L. An Overview of the Development of the Welfare Quality Assesment Systems; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Lelystad, The Netherlands, 2009; ISBN 1902647823. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, D.J.; Beausoleil, N.J.; Littlewood, K.E.; Mclean, A.N.; Mcgreevy, P.D.; Jones, B.; Wilkins, C. The 2020 Five Domains Model: Including Human-Animal Interactions in Assessments of Animal Welfare. Animals 2020, 10, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigors, B.; Lawrence, A. What Are the Positives? Exploring Positive Welfare Livestock Farmers. Animals 2019, 9, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemsworth, P.H.; Coleman, G.J.; Barnett, J.L.; Borg, S. Relationships between human-animal interactions and productivity of commercial dairy cows. J. Anim. Sci. 2000, 78, 2821–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivemeyer, S.; Knierim, U.; Waiblinger, S. Effect of human-animal relationship and management on udder health in Swiss dairy herds. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 5890–5902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pol, F.; Kling-Eveillard, F.; Champigneulle, F.; Fresnay, E.; Ducrocq, M.; Courboulay, V. Human–animal relationship influences husbandry practices, animal welfare and productivity in pig farming. Animal 2021, 15, 100103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zulkifli, I.; Siti Nor Azah, A. Fear and stress reactions, and the performance of commercial broiler chickens subjected to regular pleasant and unpleasant contacts with human being. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2004, 88, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, D.M. Individual differences in temperament of domestic dairy goats and the inhibition of milk ejection. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1989, 22, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevi, A.; Casamassima, D.; Pulina, G.; Pazzona, A. Factors of welfare reduction in dairy sheep and goats. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 8, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, K.M.A.; Hackett, D. A note: The effects of human handling on heart girth, behaviour and milk quality in dairy goats. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2007, 108, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B.R.; Tomita, G.; Hart, S.P. Effect of subclinical intramammary infection on somatic cell counts and chemical composition of goats’ milk. J. Dairy Res. 2007, 74, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Navalón, B.; Peris, C.; Gómez, E.A.; Peris, B.; Roche, M.L.; Caballero, C.; Goyena, E.; Berriatua, E. Quantitative estimation of the impact of caprine arthritis encephalitis virus infection on milk production by dairy goats. Vet. J. 2013, 197, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.W.; Fleming, P.A.; Barnes, A.L.; Wickham, S.L.; Collins, T.; Stockman, C.A. Behavioural assessment of the habituation of feral rangeland goats to an intensive farming system. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 199, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, E.M.; Mulligan, J.; Hall, S.A.; Donbavand, J.E.; Palme, R.; Aldujaili, E.; Zanella, A.J.; Dwyer, C.M. Positive and negative gestational handling influences placental traits and mother-offspring behavior in dairy goats. Physiol. Behav. 2016, 157, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, F.; Hite, A.H.; Gregorini, P. Livestock in Evolving Foodscapes and Thoughtscapes. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blokhuis, H.J.; Jones, R.B.; Geers, R.; Miele, M.; Veissier, I. Measuring and monitoring animal welfare: Transparency in the food product quality chain. Anim. Welf. 2003, 12, 445–455. [Google Scholar]

- Zobel, G.; Neave, H.W.; Webster, J. Understanding natural behavior to improve dairy goat (Capra hircus) management systems. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2019, 3, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemsworth, P.H. Human-animal interactions in livestock production. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2003, 81, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abril-Sánchez, S.; Freitas-de-Melo, A.; Beracochea, F.; Damián, J.P.; Giriboni, J.; Santiago-Moreno, J.; Ungerfeld, R. Sperm collection by transrectal ultrasound-guided massage of the accessory sex glands is less stressful than electroejaculation without altering sperm characteristics in conscious goat bucks. Theriogenology 2017, 98, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minka, N.S.; Ayo, J.O.; Sackey, A.K.B.; Adelaiye, A.B. Assessment and scoring of stresses imposed on goats during handling, loading, road transportation and unloading, and the effect of pretreatment with ascorbic acid. Livest. Sci. 2009, 125, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.A.; Mellor, D.J. Some behavioural and physiological changes in pregnant goats and sheep during adaptation to laboratory conditions. Res. Vet. Sci. 1976, 20, 215–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertenshaw, C.; Rowlinson, P.; Edge, H.; Douglas, S.; Shiel, R. The effect of different degrees of “positive” human-animal interaction during rearing on the welfare and subsequent production of commercial dairy heifers. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 114, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkifli, I.; Gilbert, J.; Liew, P.K.; Ginsos, J. The effects of regular visual contact with human beings on fear, stress, antibody and growth responses in broiler chickens. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2002, 79, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkifli, I. Review of human-animal interactions and their impact on animal productivity and welfare. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2013, 4, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcedo, M.J.; Ito, K.; Maeda, K. Stockmanship competence and its relation to productivity and economic profitability: The context of backyard goat production in the Philippines. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 28, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briefer, E.F.; McElligott, A.G. Rescued goats at a sanctuary display positive mood after former neglect. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2013, 146, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawroth, C.; McElligott, A.G. Human head orientation and eye visibility as indicators of attention for goats (Capra hircus). PeerJ 2017, 5, e3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caroprese, M.; Casamassima, D.; Rassu, S.P.G.; Napolitano, F.; Sevi, A. Monitoring the on-farm welfare of sheep and goats. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 8, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, D.; Manteca, X. Animal Welfare in Extensive Production Systems Is Still an Area of Concern. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 545902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pech, P.G.; Marín-Tun, C.G.; Valladares-González, D.A.; Ventura-Cordero, J.; Ortiz-Ocampo, G.I.; Cámara-Sarmiento, R.; Sandoval-Castro, C.A.; Torres-Acosta, J.F.J. A protocol of human animal interaction to habituate young sheep and goats for behavioural studies. Behav. Processes 2018, 157, 632–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, R.J.; Nol, P.; Ellis, C.K.; Palmer, M.V. Research with Agricultural Animals and Wildlife. ILAR J. 2019, 60, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battini, M.; Stilwell, G.; Vieira, A.; Barbieri, S.; Canali, E.; Mattiello, S. On-farm welfare assessment protocol for adult dairy goats in intensive production systems. Animals 2015, 5, 934–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, T. ‘Where goats connect people’: Cultural diffusion of livestock not food production amongst southern African hunter-gatherers during the Later Stone Age. J. Soc. Archaeol. 2017, 17, 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyd, D.D.; King, E.G.; Thompson, J.J. Goats in Schools: Parental Attitudes and Perceived Benefits. Anthrozoos 2021, 34, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koda, N.; Hirose, T.; Watanabe, G. Relationships between Caregiving to Domestic Goats and Gender and Interest in Science. Innov. Teach. 2013, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koda, N.; Kutsumi, S.; Hirose, T.; Watanabe, G. Educational possibilities of keeping goats in elementary schools in Japan. Front. Vet. Sci. 2016, 3, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholl, S.; Grall, G.; Petzl, V.; Röthler, M.; Slotta-Bachmayr, L.; Kotrschal, K. Behavioural Effects of Goats on Disabled Persons. Int. J. Ther. Communities 2008, 29, 297–309. [Google Scholar]

- Nawroth, C. Invited review: Socio-cognitive capacities of goats and their impact on human–animal interactions. Small Rumin. Res. 2017, 150, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langbein, J.; Krause, A.; Nawroth, C. Human-directed behaviour in goats is not affected by short-term positive handling. Anim. Cogn. 2018, 21, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminski, J.; Riedel, J.; Call, J.; Tomasello, M. Domestic goats, Capra hircus, follow gaze direction and use social cues in an object choice task. Anim. Behav. 2005, 69, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Malsche, F.; Cornips, L. Examining interspecies interactions in light of discourse analytic theory: A case study on the genre of human-goat communication at a petting farm. Lang. Commun. 2021, 79, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immelmann, K. Introduction to Ethology; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; ISBN 978-0-306-40489-4. [Google Scholar]

- Langbein, J.; Siebert, K.; Nuernberg, G.; Manteuffel, G. The impact of acoustical secondary reinforcement during shape discrimination learning of dwarf goats (Capra hircus). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2007, 103, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, E.J.; Rosales-Ruiz, J. A Comparison of Fixed-Time Food Schedules and Shaping Involving a Clicker for Halter Behavior in a Petting Zoo Goat. Psychol. Rec. 2021, 71, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, X.; Braastad, B.O. Effects of handling during temporary isolation after early weaning on goat kids’ later response to humans. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1996, 48, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lürzel, S.; Bückendorf, L.; Waiblinger, S.; Rault, J.L. Salivary oxytocin in pigs, cattle, and goats during positive human-animal interactions. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2020, 115, 104636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, L.O.; Bezerra, B.M.O.; Kogitzki, T.R.; Polo, G.; Freitas, V.J.D.F.; Hötzel, M.J.; Nunes-Pinheiro, D.C.S. Impact of massage on goats on the human-animal relationship and parameters linked to physiological response. Cienc. Rural 2020, 50, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastellone, V.; Scandurra, A.; D’aniello, B.; Nawroth, C.; Saggese, F.; Silvestre, P.; Lombardi, P. Long-term socialization with humans affects human-directed behavior in goats. Animals 2020, 10, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, N.; Koda, N. Goats’ Performance in Unsolvable Tasks Is Predicted by Their Reactivity Toward Humans, but Not Social Rank. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baciadonna, L.; Nawroth, C.; McElligott, A.G. Judgement bias in goats (Capra hircus): Investigating the effects of human grooming. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawroth, C.; Brett, J.M.; McElligott, A.G. Goats display audience-dependent human-directed gazing behaviour in a problem-solving task. Biol. Lett. 2016, 12, 20160283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, A.; Caicoya, A.L.; Colell, M.; Holland, R.; Ensenyat, C.; Amici, F. Gaze Following in Ungulates: Domesticated and Non-domesticated Species Follow the Gaze of Both Humans and Conspecifics in an Experimental Context. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 604904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawroth, C.; von Borell, E.; Langbein, J. ‘Goats that stare at men’—Revisited: Do dwarf goats alter their behaviour in response to eye visibility and head direction of a human? Anim. Cogn. 2016, 19, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawroth, C.; von Borell, E.; Langbein, J. ‘Goats that stare at men’: Dwarf goats alter their behaviour in response to human head orientation, but do not spontaneously use head direction as a cue in a food-related context. Anim. Cogn. 2015, 18, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawroth, C.; Martin, Z.M.; McElligott, A.G. Goats Follow Human Pointing Gestures in an Object Choice Task. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberger, K.; Simmler, M.; Langbein, J.; Keil, N.; Nawroth, C. Performance of goats in a detour and a problem-solving test following long-term cognitive test exposure. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2021, 8, 210656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-de la Lama, G.C.; Mattiello, S. The importance of social behaviour for goat welfare in livestock farming. Small Rumin. Res. 2010, 90, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, W.F.; Becker, S.E.; Katz, L.S. Urine from domesticated male goats (Capra hircus) provides attractive olfactory cues to estrous females. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 236, 105252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, H.; Terrazas, A.; Poindron, P.; Ramírez-Vera, S.; Flores, J.; Delgadillo, J.; Vielma, J.; Duarte, G.; Fernández, I.; Fitz-Rodríguez, G.; et al. Sensorial and physiological control of maternal behavior in small ruminants: Sheep and goats. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosyst. 2012, 15 (Suppl. 1), S91–S102. [Google Scholar]

- Laska, M. Human and animal olfactory capabilities compared. In Handbook of Odor; Buettner, A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing AG: Freising, Germany, 2017; pp. 675–689. [Google Scholar]

- Briefer, E.F.; McElligott, A.G. Social effects on vocal ontogeny in an ungulate, the goat, Capra hircus. Anim. Behav. 2012, 83, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briefer, E.; McElligott, A.G. Mutual mother-offspring vocal recognition in an ungulate hider species (Capra hircus). Anim. Cogn. 2011, 14, 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baciadonna, L.; Briefer, E.F.; Favaro, L.; McElligott, A.G. Goats distinguish between positive and negative emotion-linked vocalisations. Front. Zool. 2019, 16, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, K.; Langbein, J.; Schön, P.C.; Tuchscherer, A.; Puppe, B. Degree of social isolation affects behavioural and vocal response patterns in dwarf goats (Capra hircus). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2011, 131, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briefer, E.; McElligott, A.G. Indicators of age, body size and sex in goat kid calls revealed using the source-filter theory. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2011, 133, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baciadonna, L.; Briefer, E.F.; McElligott, A.G. Investigation of reward quality-related behaviour as a tool to assess emotions. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2020, 225, 104968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briefer, E.F.; Tettamanti, F.; McElligott, A.G. Emotions in goats: Mapping physiological, behavioural and vocal profiles. Anim. Behav. 2015, 99, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houpt, K. Domestic Animal Behavior for Veterinarians and Animal Scientists, 4th ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Ames, IA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Laurijs, K.A.; Briefer, E.F.; Reimert, I.; Webb, L.E. Vocalisations in farm animals: A step towards positive welfare assessment. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 236, 105264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Neindre, P.; Boivin, X.; Boissy, A. Handling of extensively kept animals. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1996, 49, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, D.M.; Price, E.O.; Moberg, G.P. Individual differences in temperament of domestic dairy goats: Constancy and change. Anim. Behav. 1988, 36, 1323–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-de la Lama, G.C.; Pinal, R.; Fuchs, K.; Montaldo, H.H.; Ducoing, A.; Galindo, F. Environmental enrichment and social rank affects the fear and stress response to regular handling of dairy goats. J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 2013, 8, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemsworth, P.H.; Barnett, J.L.; Coleman, G.J. The integration of human-animal relations into animal welfare monitoring schemes. Anim. Welf. 2009, 18, 335–345. [Google Scholar]

- Beaujouan, J.; Cromer, D.; Boivin, X. Review: From human–animal relation practice research to the development of the livestock farmer’s activity: An ergonomics–applied ethology interaction. Animal 2021, 15, 100395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toinon, C.; Waiblinger, S.; Rault, J.L. Maternal deprivation affects goat kids’ stress coping behaviour. Physiol. Behav. 2021, 239, 113494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finan, A. For the love of goats: The advantages of alterity. Agric. Human Values 2011, 28, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiezzi, F.; Tomassone, L.; Mancin, G.; Cornale, P.; Tarantola, M. The Assessment of Housing Conditions, Management, Animal-Based Measure of Dairy Goats’ Welfare and Its Association with Productive and Reproductive Traits. Animals 2019, 9, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersmann, D.; Schmied-Wagner, C.; Nordmann, E.; Graml, C.; Waiblinger, S. Influences on the avoidance and approach behaviour of dairy goats towards an unfamiliar human-An on-farm study. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 179, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battini, M.; Barbieri, S.; Vieira, A.; Stilwell, G.; Mattiello, S. Results of testing the prototype of the awin welfare assessment protocol for dairy goats in 30 intensive farms in northern Italy. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 15, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molale, G.; Antwi, M.A.; Lekunze, J.N.; Luvhengo, U. General linear model analysis of behavioural responses of Boer and Tswana goats to successive handling. Indian J. Anim. Res. 2017, 51, 781–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndou, S.P.; Muchenje, V.; Chimonyo, M. Behavioural responses of four goat genotypes to successive handling at the farm. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 9, 8118–8124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, E.; Vieira, A.; Battini, M.; Mattiello, S.; Stilwell, G. On-farm welfare assessment of dairy goat farms using animal-based indicators: The example of 30 commercial farms in Portugal. Acta Agric. Scand. A Anim. Sci. 2016, 66, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muri, K.; Tufte, P.A.; Skjerve, E.; Valle, P.S. Human-animal relationships in the Norwegian dairy goat industry: Attitudes and empathy towards goats (Part I). Anim. Welf. 2012, 21, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muri, K.; Stubsjøen, S.M.; Valle, P.S. Development and testing of an on-farm welfare assessment protocol for dairy goats. Anim. Welf. 2013, 22, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-de la Lama, G.C.; Sepúlveda, W.S.; Montaldo, H.H.; María, G.A.; Galindo, F. Social strategies associated with identity profiles in dairy goats. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2011, 134, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, G.J.; Hemsworth, P.H.; Hay, M. Predicting stockperson behaviour towards pigs from attitudinal and job-related variables and empathy. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1998, 58, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waiblinger, S.; Menke, C.; Coleman, G. The relationship between attitudes, personal characteristics and behaviour of stockpeople and subsequent behaviour and production of dairy cows. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2002, 79, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, D.; Sneddon, I.A.; Beattie, V.E. The relationship between the stockpersons personality and attitudes and the productivity of dairy cows. Animal 2009, 3, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemsworth, P.; Coleman, G. Human-Livestock Interactions: The Stockperson and the Productivity and Welfare of Intensively Farmed Animals, 2nd ed.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, F.; Christley, R.; Campe, A. Invited review: Examining farmers’ personalities and attitudes as possible risk factors for dairy cattle health, welfare, productivity, and farm management: A systematic scoping review. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 3805–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windschnurer, I.; Eibl, C.; Franz, S.; Gilhofer, E.M.; Waiblinger, S. Alpaca and llama behaviour during handling and its associations with caretaker attitudes and human-animal contact. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2020, 226, 104989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, A.F.; Sanchez, J.A.; Romero, M.H. Association between attitude and empathy with the quality of human-livestock interactions. Animals 2020, 10, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serpell, J.A. Factors influencing human attitudes to animals and their welfare. Anim. Welf. 2004, 13, 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog, H.A. Gender differences in human-animal interactions: A review. Anthrozoos 2007, 20, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcher, J.; Cousson-Gélie, F.; Dantzer, R. Affective components of the human-animal relationship in animal husbandry: Development and validation of a questionnaire. Physiol. Rep. 2004, 95, 275–290. [Google Scholar]

- Apostol, L.; Rebega, O.L.; Miclea, M. Psychological and Socio-demographic Predictors of Attitudes toward Animals. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 78, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Miller, P.A. The Relation of Empathy to Prosocial and Related Behaviors. Psychol. Bull. 1987, 101, 91–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grynberg, D.; Konrath, S. The closer you feel, the more you care: Positive associations between closeness, pain intensity rating, empathic concern and personal distress to someone in pain. Acta Psychol. 2020, 210, 103175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, E.S. Empathy with animals and with humans: Are they linked? Anthrozoos 2000, 13, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingsen, K.; Zanella, A.J.; Bjerkås, E.; Indrebø, A. The relationship between empathy, perception of pain and attitudes toward pets among Norwegian dog owners. Anthrozoos 2010, 23, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kielland, C.; Skjerve, E.; Østerås, O.; Zanella, A.J. Dairy farmer attitudes and empathy toward animals are associated with animal welfare indicators. J. Dairy Sci. 2010, 93, 2998–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norring, M.; Wikman, I.; Hokkanen, A.H.; Kujala, M.V.; Hänninen, L. Empathic veterinarians score cattle pain higher. Vet. J. 2014, 200, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. Psychology of Attitudes; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Muri, K.; Valle, P.S. Human-animal relationships in the Norwegian dairy goat industry: Assessment of pain and provision of veterinary treatment (Part II). Anim. Welf. 2012, 21, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattiello, S.; Battini, M.; Andreoli, E.; Minero, M.; Barbieri, S.; Canali, E. Avoidance distance test in goats: A comparison with its application in cows. Small Rumin. Res. 2010, 91, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, D.M.; Price, E.O. Relationships between heart rates and behaviour of goats in encounters with people. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1987, 18, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, D.M.; Price, E.O.; Moberg, G.P. Social modulation of pituitary–adrenal responsiveness and individual differences in behavior of young domestic goats. Physiol. Behav. 1988, 43, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battini, M.; Barbieri, S.; Waiblinger, S.; Mattiello, S. Validity and feasibility of Human-Animal Relationship tests for on-farm welfare assessment in dairy goats. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 178, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, L.O.; Stamm, F.O.; Souza, R.A.; Camarinha Filho, J.A.; Garcia, R.C.M. On-farm welfare assessment in dairy goats in the Brazilian Northeast. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2020, 72, 2308–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battini, M.; Renna, M.; Giammarino, M.; Battaglini, L.; Mattiello, S. Feasibility and Reliability of the AWIN Welfare Assessment Protocol for Dairy Goats in Semi-extensive Farming Conditions. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 731927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, L.O.; Stamm, F.D.O.; Maceno, M.A.C.; Camarinha Filho, J.A.; Garcia, R.D.C.M. On-farm welfare assessment in meat goat does raised in semi-intensive and extensive systems in semiarid regions of ceará, Northeast, Brazil. Cienc. Rural 2020, 50, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markland, M.L.; Goering, M.J.; Mumm, J.M.; Jones, C.K.; Crane, A.R.; Hulbert, L.E. The development of a noninvasive behavioral test for assessment of goat-human interactions. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2019, 3, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AWIN. AWIN Welfare Assessment Protocol for Goats; AWIN, 2015; Volume 70, Available online: https://air.unimi.it/retrieve/handle/2434/269102/384790/AWINProtocolGoats.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Can, E.; Vieira, A.; Battini, M.; Mattiello, S.; Stilwell, G. Consistency over time of animal-based welfare indicators as a further step for developing a welfare assessment monitoring scheme: The case of the Animal Welfare Indicators protocol for dairy goats. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 9194–9204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waiblinger, S.; Menke, C.; Fölsch, D.W. Influences on the avoidance and approach behaviour of dairy cows towards humans on 35 farms. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2003, 84, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battini, M.; Andreoli, E.; Barbieri, S.; Mattiello, S. Long-term stability of Avoidance Distance tests for on-farm assessment of dairy cow relationship to humans in alpine traditional husbandry systems. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2011, 135, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AWIN. AWIN Welfare Assessment Protocol for Sheep; AWIN, 2015; Volume 69, Available online: https://air.unimi.it/retrieve/handle/2434/269114/384851/AWINProtocolSheep.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Richmond, S.E.; Wemelsfelder, F.; de Heredia, I.B.; Ruiz, R.; Canali, E.; Dwyer, C.M. Evaluation of Animal-Based Indicators to Be Used in a Welfare Assessment Protocol for Sheep. Front. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lürzel, S.; Barth, K.; Windschnurer, I.; Futschik, A.; Waiblinger, S. The influence of gentle interactions with an experimenter during milking on dairy cows’ avoidance distance and milk yield, flow and composition. Animal 2018, 12, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crockford, C.; Wittig, R.M.; Langergraber, K.; Ziegler, T.E.; Zuberbühler, K.; Deschner, T. Urinary oxytocin and social bonding in related and unrelated wild chimpanzees. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 280, 20122765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, C.A.; Coleman, G.J.; Hemsworth, P.H.; Campbell, A.J.D.; Doyle, R.E. Positive attitudes, positive outcomes: The relationship between farmer attitudes, management behaviour and sheep welfare. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemsworth, P.H.; Coleman, G.J.; Barnett, J.L.; Borg, S.; Dowling, S. The effects of cognitive behavioral intervention on the attitude and behavior of stockpersons and the behavior and productivity of commercial dairy cows. J. Anim. Sci. 2002, 80, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, D. Farm animal production: Changing agriculture in a changing culture. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2001, 4, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raussi, S. Human ± cattle interactions in group housing. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2003, 80, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoolder, H.; Ruis, M. Improving Farm Animal Productivity and Welfare, by Increasing Skills and Knowledge of Stock People. In Animal Environment and Welfare; Ni, J.Q., Lim, T.T., Wang, C., Eds.; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2015; pp. 269–277. [Google Scholar]

- Millman, S.T. Animal Welfare—Scientific approaches to the issues. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2009, 12, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mota-Rojas, D.; Broom, D.M.; Orihuela, A.; Velarde, A.; Napolitano, F.; Alonso-Spilsbury, M. Effects of human-animal relationship on animal productivity and welfare. J. Anim. Behav. Biometeorol. 2020, 8, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawroth, C.; Langbein, J.; Coulon, M.; Gabor, V.; Oesterwind, S.; Benz-Schwarzburg, J.; von Borell, E. Farm animal cognition-linking behavior, welfare and ethics. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, L.; Colvin, C. Thinking Pigs: A Comparative Review of Cognition, Emotion, and Personality in Sus domesticus. Int. J. Comp. Psychol. 2015, 28, 23859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendl, M.; Burman, O.H.P.; Paul, E.S. An integrative and functional framework for the study of animal emotion and mood. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 277, 2895–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daros, R.R.; Costa, J.H.C.; Von Keyserlingk, M.A.G.; Hötzel, M.J.; Weary, D.M. Separation from the dam causes negative judgement bias in dairy calves. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, L. Thinking chickens: A review of cognition, emotion, and behavior in the domestic chicken. Anim. Cogn. 2017, 20, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, N.M.; Imfeld-Mueller, S.; Aschwanden, J.; Wechsler, B. Are head cues necessary for goats (Capra hircus) in recognising group members? Anim. Cogn. 2012, 15, 913–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitcher, B.J.; Briefer, E.F.; Baciadonna, L.; McElligott, A.G. Cross-modal recognition of familiar conspecifics in goats. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2017, 4, 160346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgs, M.J.; Bipin, S.; Cassaday, H.J. Man’s best friends: Attitudes towards the use of different kinds of animal depend on belief in different species’ mental capacities and purpose of use. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 191162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, S.; Barnett, L. Justifying attitudes toward animal use: A qualitative study of people’s views and beliefs. Anthrozoos 2008, 21, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, S.; Vrij, A.; Cherryman, J.; Nunkoosing, K. Attitudes towards animal use and belief in animal mind. Anthrozoos 2004, 17, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waiblinger, S.; Wagner, K.; Hillmann, E.; Barth, K. Short-and long-term effects of rearing dairy calves with contact to their mother on their reactions towards humans. J. Dairy Res. 2020, 87, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiot, C.E.; Bastian, B. Toward a psychology of human-animal relations. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 6–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, G.J.; Hay, M.; Hemsworth, P.H.; Cox, M. Modifying stockperson attitudes and behaviour towards pigs at a large commercial farm. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2000, 66, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lensink, B.J.; Fernandez, X.; Boivin, X.; Pradel, P. The impact of gentle contacts on ease of handling, welfare, and growth of calves and on quality of veal meat. J. Anim. Sci. 2000, 78, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauppinen, T.; Valros, A.; Vesala, K.M. Attitudes of dairy farmers toward cow welfare in relation to housing, management and productivity. Anthrozoos 2013, 26, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. The advantages of an inclusive definition of attitude. Soc. Cogn. 2007, 25, 582–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, J.J. Determinants of subjective well-being among farm operators: Characteristics of the individual and the firm. Rural Sociol. 1985, 50, 141–162. [Google Scholar]

- Muri, K.; Tufte, P.A.; Coleman, G.; Oppermann, M.R. Exploring Work-Related Characteristics as Predictors of Norwegian Sheep Farmers’ Affective Job Satisfaction. Sociol. Rural. 2020, 60, 574–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, V.; Coleman, G.; Gunnarsson, S.; Appleby, M.C.; Karkinen, K. Animal welfare science—Working at the interface between the natural and social sciences. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2006, 97, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Signal Category 1 | Behaviour | Emitter | Receiver | Meaning/Goal | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Acoustic signals at different tones | Human | Goat | Training to shape discrimination | [52] |

| A | Clicker sound previously associated with food reward | Human | Goat | Training to wear a halter | [53] |

| A | Loud vocalizations | Human | Pregnant goat | Negative handling treatment | [23] |

| A | Speaking | Human | Goat kids | Positive handling treatment | [54] |

| A | Speaking in a soft voice | Human | Pregnant goat | Positive handling treatment | [23] |

| A | Speaking in a soft voice | Human | Goat | Inviting goats to approach + positive handling treatment | [55] |

| A | Vocal call “Come here” | Human | Goat | Call for goat’s attention | [36] |

| A | Vocal call “Come here” or “Come on, honey” | Human | Goat kids | Call for goat’s attention | [50] |

| G | Licking | Goat | Human | Positive feelings, search for contact | [56] |

| O | Smelling | Goat | Human | Positive feelings, search for contact | [56] |

| T | Biting and pulling human’s clothes | Goat | Human | Negative feelings, discomfort | [56] |

| T | Contact alternation (frequency and latency) | Goat | Human | Asking for help to solve problem | [48] |

| T | Establishing physical contact (rubbing, nosing, pawing a hand or leg or jumping up) | Goat | Human | Asking for help to solve problem | [57] |

| T | Physical contact (latency and duration) | Goat | Human | Asking for help to solve problem | [58] |

| T | Pushing human’s arm and hands with head/horns | Goat | Human | Negative feelings, discomfort | [56] |

| T | Rubbing the head, placing it on human’s lap | Goat | Human | Positive feelings, search for contact | [56] |

| T | Brushing head and back | Human | Goat | Inducing changes of emotional state | [59] |

| T | Massage | Human | Goat | Promoting goats’ relaxation, improvement of HAR | [56] |

| T | Petting, scratching, stroking | Human | Goat | Positive handling treatment | [55] |

| T | Petting, stroking and scratching | Human | Pregnant goat | Positive handling treatment | [23] |

| T | Stroking | Human | Goat kids | Positive handling treatment | [54] |

| T | Stroking | Human | Goat | Positive handling treatment | [19] |

| T | Touching, stroking and brushing | Human | Goat | Establishing contact with goats | [46] |

| T/G | Chewing (contact of goat’s mouth with humans) | Goat | Human | Refusing to wear a halter | [53] |

| T/G | Nibbling | Goat | Human | Positive feelings, search for contact | [56] |

| T/G | Nibbling human clothes | Goat | Human | Two hypotheses: search for social contact or replacement behaviour in a poorly enriched environment? | [50] |

| V | Approaching | Goat | Human | Establishing contact with humans | [55] |

| V | Establishing visual contact | Goat | Human | Asking for help to solve problem | [57] |

| V | Gaze alternation (frequency and latency) | Goat | Human | Asking for help to solve problem | [48] |

| V | Gazing | Goat | Human | Searching for cues on hidden food | [60] |

| V | Moving away from the trainer | Goat | Human | Refusing to wear a halter | [53] |

| V | Moving toward the trainer | Goat | Human | Establishing contact with the trainer | [53] |

| V | Standing in front of the trainer | Goat | Human | Establishing contact with the trainer | [53] |

| V | Turning (90°) of goat’s neck/head | Goat | Human | Refusing to wear a halter | [53] |

| V | Turning head and directing gaze away from the milk bottle | Goat kids | Human | Not interested in drinking milk | [50] |

| V | Body orientation | Human | Goat | Stimulating approach behaviour | [36] |

| V | Facial expressions | Human | Goat | Stimulating approach and interaction | [7] |

| V | Gazing | Human | Goat | Indicating a given direction | [61] |

| V | Head and body orientation | Human | Goat | Providing for cues on hidden food | [62] |

| V | Offering food | Human | Goat | Inviting goats to approach | [50] |

| V | Offering food (twigs) | Human | Goat | Inviting goats to approach | [46] |

| V | Open vs. closed eyes | Human | Goat | Stimulating approach behaviour | [36] |

| V | Pointing the arm | Human | Goat | Providing cues on hidden food | [49] |

| V | Pointing the arm | Human | Goat | Providing cues on hidden food | [63,64] |

| V | Slow arm and hand movements | Human | Goat | Inviting goats to approach | [55] |

| V | Touching object | Human | Goat | Providing cues on hidden food | [63] |

| V | Touching object and moving the arm | Human | Goat | Providing cues on hidden food | [49] |

| V/A | Shacking a food container | Human | Goat | Attract goats’ attention | [65] |

| Factor Type 1 | Factor | Effect on HAR | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| E | Human rearing of goat kids | >time of kids in proximity with humans in goat-human encounter test <latency of kids to approach humans in goat-human encounter test <kids’ flight distance in goat-human encounter test | [80] |

| E | Human rearing of goat kids | <kids’ avoidance distance in AD 2 test | [84] |

| E | Human rearing of goat kids | >confidence of kids with humans >ease of management in adulthood | [85] |

| E | Human rearing of goat kids | <flight distance in encounter and choice test >time in proximity with humans in encounter and choice test | [54] |

| E | Human rearing of goat kids | <latency of adult goats to approach human in encounter test in the home pen >time of adult goats in proximity of humans in encounter test in the home pen | [17] |

| E | Frequent contacts with visitors (in zoo) | >human-directed behaviour in an impossible task paradigm | [57] |

| E | Frequent contact with humans (entering the goat pen twice/day and walking calmly among the goats for 20 min) | <flight speed of feral rangeland goats in a flight response test | [22] |

| E | Farming system (intensive vs. semi-extensive) | <latency to the first contact in intensive farms | [86] |

| E | Gentling treatment (friendly talking, gentle touching, stroking and hand feeding twice daily, over two weeks) | Performing of alternation of gaze and contact towards the human being in an unsolvable task paradigm | [48] |

| E | Gentling treatment (stroking goats’ back and neck with eye contact for 10 min for 24 days) | Quicker approach to the experimenter in latency test faster habituation to the presence of the experimenter | [19] |

| E | Proportion of negative interactions during milking (e.g., talking harshly, hitting and kicking the goats) | >avoidance behaviour in goats; <approach behaviour in goats | [87] |

| E | Small farm size, low goats/stockperson ratio | >% of acceptance and contact with human in AD 2 test | [88] |

| E | Presence of environmental enrichments (i.e., tractor tyres; heap of compacted earth) | >distance from the human experimenter in a handling test | [81] |

| I | Temperament | >latency to proximity and latency to contact in different test situations in “timid” goats | [17,80] |

| I | Breed | Boer vs. Tswana, Nguni and Xhosa lob-eared genotype: >flight times during handling; <flight speed during handling; <vocalization score during handling; <crush score (CS) 3 during handling | [89,90] |

| I | Breed | Saanen and Murciano-Granadina easier to handle than more rustic breeds (hypothesis) | [91] |

| I | Low social rank | >proximity to a stationary human; <time to get used to stress due to handling and restraint | [81] |

| I | High social rank | >distance from a stationary human; >time to get used to stress due to handling and restraint | [81] |

| H | Considering goats pleasant animals | >possibility of pain recognition in goats | [92] |

| H | Higher empathy | >positive attitudes in relation to goats and working with them | [92] |

| H | Being raised on a farm | <human consideration of the goat as a pleasant animal to work with, entertaining and intelligent | [92] |

| H | Stockperson’s gender | in women >ability to interpret and understand goats’ experience and find easier to work with goats | [92] |

| H | Belief in the importance of positive contact with goats (i.e., stroking) | >goats’ willingness to be touched | [93] |

| Category | Assessor Behaviour | Assessor | Animal Category | Test Context | Social Context | Procedure | Variables | Validity 1 | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stationary human | Motionless | Not specified | Adult | Test environment | Isolation | Goat restraint in a starting zone for 45 s and released in the arena with an assessor standing | Latency of proximity with the human, duration in proximity (within 2 m), sections crossed, mean distance from the humans | Y | [80] |

| Stationary human | Motionless | Unfamiliar | Adult | Test environment | Audience | Goat placed 5 min in the arena, peers behind a fence, then assessor enters and stays still for 5 min. Heart rate recorded by telemetry. | Duration in contact with the human, number of vocalisations, heart rate. | Y | [115] |

| Stationary human (1); Moving human (2) | (1) seated human standing still, but moving the hand; (2) human approaching | Familiar | Kids | Test environment | Isolation | Two phases. Seated human: goat left alone in arena for 1 min, assessor enters and stands still for 1.5 min, stroking the kid if approaching. Moving human: the assessor approaches and tries to pet kid for 1.5 min | Duration in proximity (<2 m), in contact with the human. Vocalisation, sections crossed | Y | [54] |

| Stationary human; Moving human | (1) and (2) motionless; (3) human approaching | Unfamiliar | Adult/Kids | Home environment, indoor | Group/Isolation | Three phases. (1) assessor enters pen and stands still, (2) assessor moves back and forth along the front fence, (3) assessor tries to touch goats | Latencies to approach the human (<1 m) and to make contact, duration in proximity (stationary or moving) | Y | [17,116] |

| Moving human | Human approaching | Unfamiliar | Adult | Test environment | Isolation | Goat placed in a circular runway, assessor walks (0.5 steps/s) behind it for 3.5 min. Blood sampling taken 3 days before the test, immediately after and 3 days after | Mean flight distance, following, approach, avoidance, vocalisation, human contact, urination (plasma cortisol) | Y | [80] |

| Handling | Handling | Familiar | Adult | Home environment, indoor | Group | Goats milked twice daily for 21 days by two persons. Then, the same persons score each goats behaviour | Seven behavioural scales: excitable, tense, watchful, apprehensive, confident, friendly to humans, fearful of humans. Milk ejection. | Y | [17] |

| Stationary human | Motionless | Unfamiliar | Adult | Home environment, indoor | Group | Assessor enters the pen and walks to a pre-determined spot, marking a 1.5-radius semi-circumference and starts the stopwatch. Assessor stands motionless for 5 min, back against the wall | Latency to the first contact performed by the first goat, percentage of goats that nuzzled or touched any part of the assessor (continuously recorded and at 1 min-scan), percentage of goats that entered the semi-circumference around the assessor, at 1 min-scan | Y | [117] |

| Moving human | Human approaching | Unfamiliar | Adult | Home environment, indoor | Group | The assessor enters the pen and stands in front of a goat (randomly chosen) at a distance of 300 cm, then starts moving slowly towards the animal at a speed of one step/s, 60 cm/step and the arm lifted with an inclination of 45°, the hand palm directed downwards, without looking into the animal’s eyes, but looking at the muzzle. When the goat shows the first avoidance reaction (moving back-wards, turning or shaking its head), the assessor recorded the distance between the hand and the muzzle of the animal, with a resolution of 10 cm. If the animal can be touched by the assessor, the distance is 0, and this is also defined as “contact”. | Mean avoidance distance (cm) of the goats tested in the pen, percentage of goats that can be touched by the assessor during the AD test | n.t. | [114] |

| Moving human | Human approaching | Unfamiliar | Adult | Home environment, indoor | Group | Same procedure as [114] but with a starting distance of 200 cm. If the animal can be touched by the assessor but immediately withdraws, this is recorded as “contact”; if, after the contact, the animal accepts gently stroking of the head for at least 3 s, this is recorded as “acceptance”. | Mean avoidance distance (cm) of the goats tested in the pen, percentage of goats that nuzzle or touch the hand of assessor during the AD test, percentage of goats that accept gently stroking of the head by the assessor for at least 3 sec during the AD test, percentage of goats tested | Y | [117] |

| Stationary human | Motionless | Unfamiliar | Adult | Home environment, indoor | Group | Assessor enters the pen and walks to a pre-determined spot, possibly in the middle of the long side of the pen. Then starts the stopwatch and stands motionless for 5 min, back against the wall | Latency to the first contact performed by the first goat | Y | [86,91,117,118] |

| Moving human | Human approaching and/or calling | Familiar | Adult | Home environment, outdoor | Group | The farmer approaches the goats in the usual manner. The assessor (out of sight of the animals) records the reaction of goats toward the farmer. | Three possible reactions of goats are recorded: avoidance, contact, approach | n.t. | [119] |

| Moving human | Human approaching and/or calling | Familiar | Adult | Home environment, outdoor | Group | The closest distance (m) of approach the group, before a flight response is evoked, is recorded. If an animal stands motionless, this is recorded as 0 m. Animals that voluntary approach the farmer and/or interact (sniffing or touching) are also recorded. | Mean avoidance distance (cm), percentage of animals voluntary seeking for human contacts | n.t. | [120] |

| Handling | Handling | Familiar | Adult | Home environment, indoor | Group | Unaware of being tested, the stockperson approaches and marks individual pre-selected goats on the head with a marking crayon, while an assessor evaluate his/her behavioural style, as well as the goats’ behavioural responses during the procedure | Behavioural responses registered on five-point rating scales (1 = positive interactions; 5 = negative interactions) | Y | [93] |

| Stationary human | Human standing still, moving the hand | Unfamiliar | Adult | Home environment, indoor | Group | Chin contact test—The assessor stands in front of each goat, reaches out an arm with the palm pointing upwards, and gently moves the hand towards the goat’s chin. | The goat’s response to the hand is registered on a three-point scale: full acceptance, brief touch, full avoidance | Y | [93] |

| Moving human | Human approaching | Unfamiliar/familiar | Adult | Test environment | Group | 3-min human approach test conducted after first- and seventh-handling experience of goats. Three main categories of reactions: (1) spatial (close, middle, far), (2) orientation (facing vs. turned-away), (3) structural (lie, stand, and nutritive and non-nutritive oral behaviours). | Percentage of duration of behaviour outcomes to create an approach index (AI): great approach (≥75% quartile), moderate approach (25% to 75% quartiles), least approach (≤25%) | n.t. | [121] |

| Moving human | Human walking along the feeding alley | Unfamiliar | Adult | Home environment, indoor | Group | Avoidance test at the feeding place—The assessor walks on the feeding alley with 0.5 steps/s, at a distance of about 80 cm parallel to the feed barrier, assessing the reaction of feeding goats as the assessor passes by, | Percentage of animals still feeding when the assessor passes by | Y | [87] |

| Moving human | Human approaching | Unfamiliar | Adult | Home environment, indoor | Group | Avoidance distance test at the feeding place—From a distance of 200 cm, the assessor approaches individual animals than stand at the feeding place, constantly walking (speed of 0.5/s, steps of about 30–40 cm) with one arm 45° in front of the body, fingertips pointing to the ground and back of the hand towards the goat, until the goat withdrew or until touching. In case the goat can be touched but withdraws within 2 s an avoidance distance of 1 cm is assigned. Only when a goat accepts being stroked for more than 2 s an avoidance distance of 0 cm is assigned | Median value of avoidance distance at the feeding place, percentage of animals possible to stroke, percentage of animals with an avoidance distance greater than 1 m | Y | [87] |

| Stationary human | Motionless | Unfamiliar | Adult | Home environment, indoor | Group | Approach test in the pen—The assessor enters the pen and after a 30–34 s pause walks to a pre-decided testing place in the pen and marks three positions in a radius of 3 m. Then, the assessor stands 15 min motionless with the back to a wall. | Absolute number of goats into physical contact with the assessor, latency of the first animal touching the assessor (1-min scan), average number of goats within the 3 m radius (1-min scan), proportion of goats within 0.5 m to the assessor during the first 5 min | N | [87] |

| Moving human | Human approaching | Unfamiliar | Adult | Home environment, indoor | Group | Avoidance test in the pen—Two successive phases. Phase 1: the assessor walks for 1–2 min through the pen and observes the distance of the goats being closest to him/her. Phase 2: after leaving the pen for at least 2 min, the assessor re-enters the pen and approaches single animals, trying to touch them | Phase 1: estimation of the average distance from the group over the whole time. Phase 2: percentage of animals that can be touched | Y | [87] |

| Moving human | Human approaching | Familiar | Adult | Test environment | Group | Starting from a distance of 20 m, the assessor approaches the goats at a slow walking speed (1.5 m/s). When the flight response is induced, the assessor stops still after all the goats have run past. | Distance that the assessor approaches the group of goats at the time that all the goats run past, average speed at which the goats run past and away from the assessor | N | [22] |

| Stationary human | Motionless | Unfamiliar | Adult | Test environment | Isolation | The assessor keeps the eyes on the goat without moving the face or body for 5 min. | Behaviours: gazing, proximity (within 50 cm), contacting (at a distance of 1 to 10 cm) | n.t. | [58] |

| Moving human | Human approaching | Unfamiliar | Adult | Test environment | Isolation | The assessor approaches a goat leashed (1-m rope) on the side of the paddock, walking obliquely at a pace of 1 step/sec. If the goat remains stationary within 1.5 m, the assessor slowly moves the hand close to the face of the goat. If the goat does not escape and tries to smell the hand, the assessor tries to touch the goat’s neck. | Scores (1 to 4): (1) goat moves away from the assessor (>1.5 m range), (2) goat stands still when the assessor is within 1.5 m range, (3) goat sniffs the assessor’s hand, (4) the assessor touches goat’s neck | n.t. | [58] |

| Stationary human | Motionless | Unfamiliar | Adult | Home environment, indoor | Group | The assessor moves to approximately the middle of the pen and begins timing the latency for each animal to approach within 60 cm. This measurement is capped at 10 min regardless of whether or not the animal approaches. | Latency to approach | n.t. | [19] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Celozzi, S.; Battini, M.; Prato-Previde, E.; Mattiello, S. Humans and Goats: Improving Knowledge for a Better Relationship. Animals 2022, 12, 774. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12060774

Celozzi S, Battini M, Prato-Previde E, Mattiello S. Humans and Goats: Improving Knowledge for a Better Relationship. Animals. 2022; 12(6):774. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12060774

Chicago/Turabian StyleCelozzi, Stefania, Monica Battini, Emanuela Prato-Previde, and Silvana Mattiello. 2022. "Humans and Goats: Improving Knowledge for a Better Relationship" Animals 12, no. 6: 774. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12060774

APA StyleCelozzi, S., Battini, M., Prato-Previde, E., & Mattiello, S. (2022). Humans and Goats: Improving Knowledge for a Better Relationship. Animals, 12(6), 774. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12060774