Before Azaria: A Historical Perspective on Dingo Attacks

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

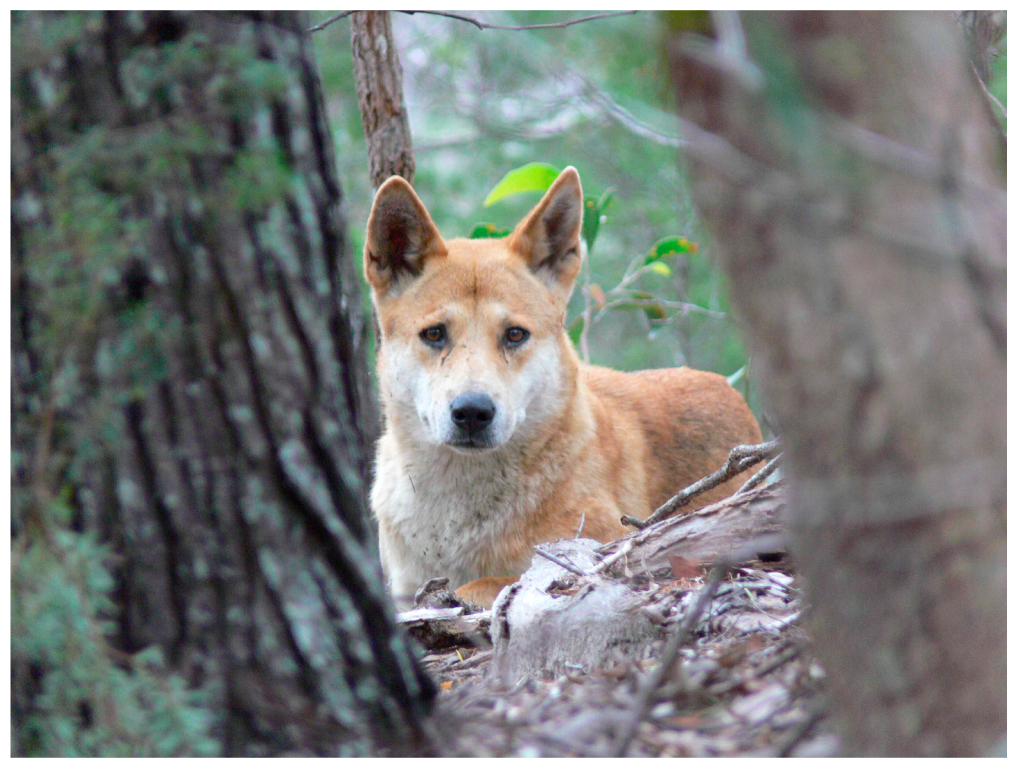

1. Introduction

When we tried to document some of these incidents for court, we were told they were too early to be listed in court records, considered irrelevant, or misleading (since they were usually listed as death by ‘misadventure’), or just reported in local newspapers of the day[9] (p. 91)

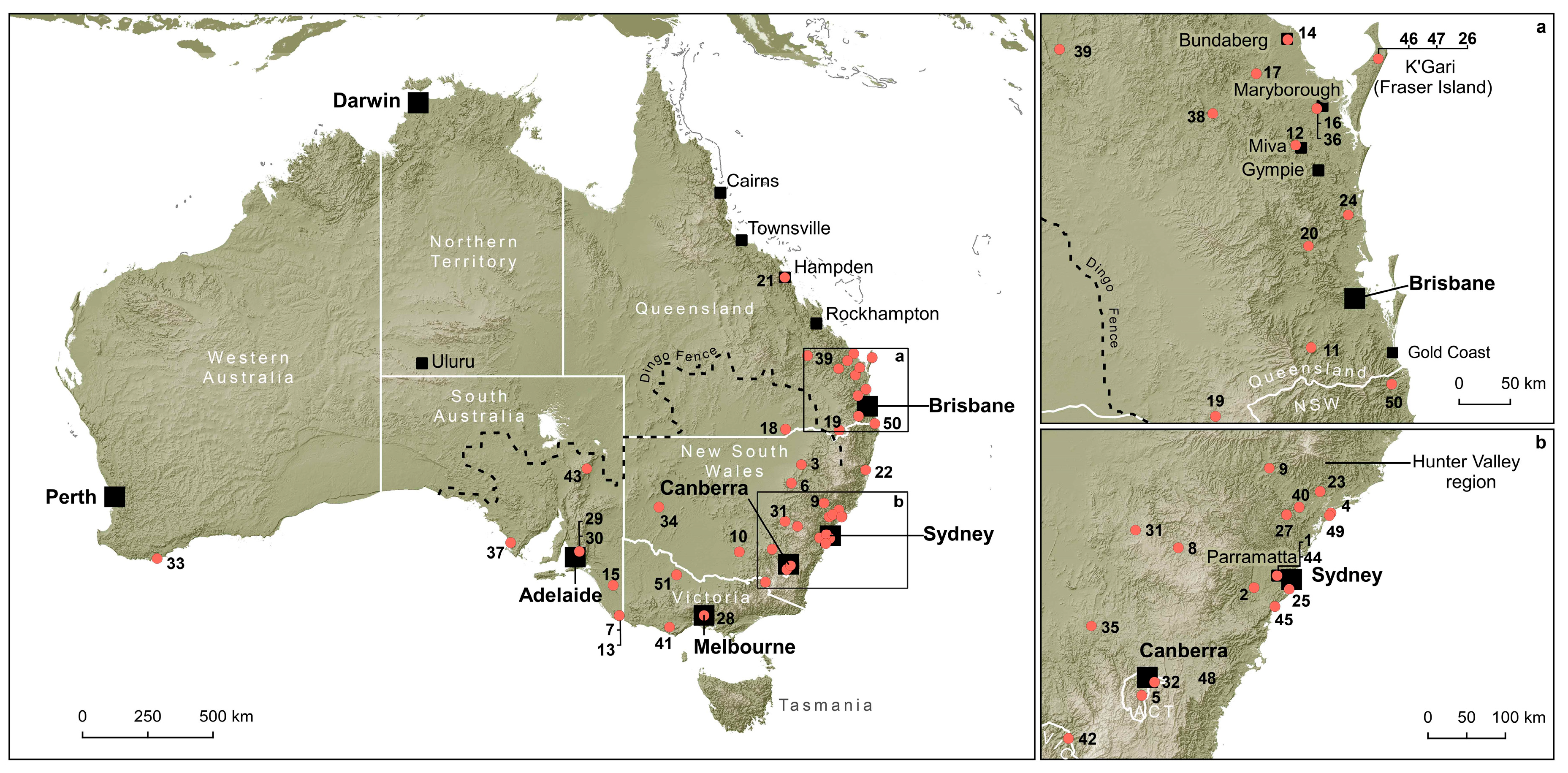

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Compiling a List of Historical Accounts of Dingo Attacks

2.2. Investigating Earlier Cultural Attitudes towards Dingoes

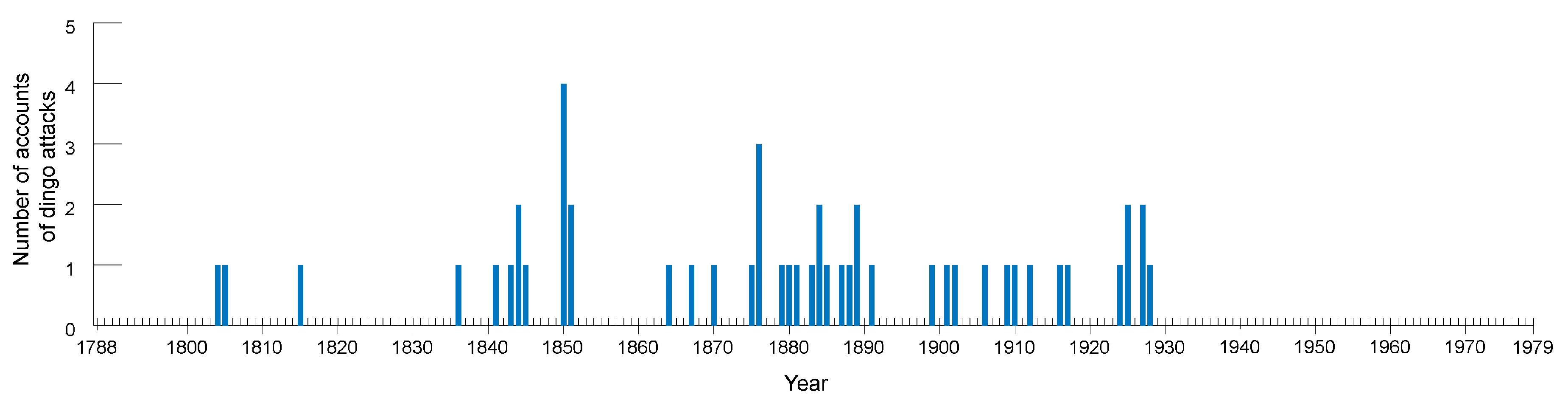

3. Results: Historical Accounts of Dingo Attacks

3.1. Comparison with Modern Dingo Attacks

Some time later he was startled awake by dingoes sinking their teeth into his limbs. He tried to fight them off, hitting out at them as they bit him. However, if he scared one off, another ran in, snapping, biting and taking turns to clamp down on his arms and legs[43] (p. 98)

He received bites and skin tears and the dogs tore at his shorts. He ended up on the ground and they continued to bite him on the legs and the head, but he tucked himself up into a ball with his knees into chest to try and protect himself and he managed to protect his throat and his stomach and groin[44]

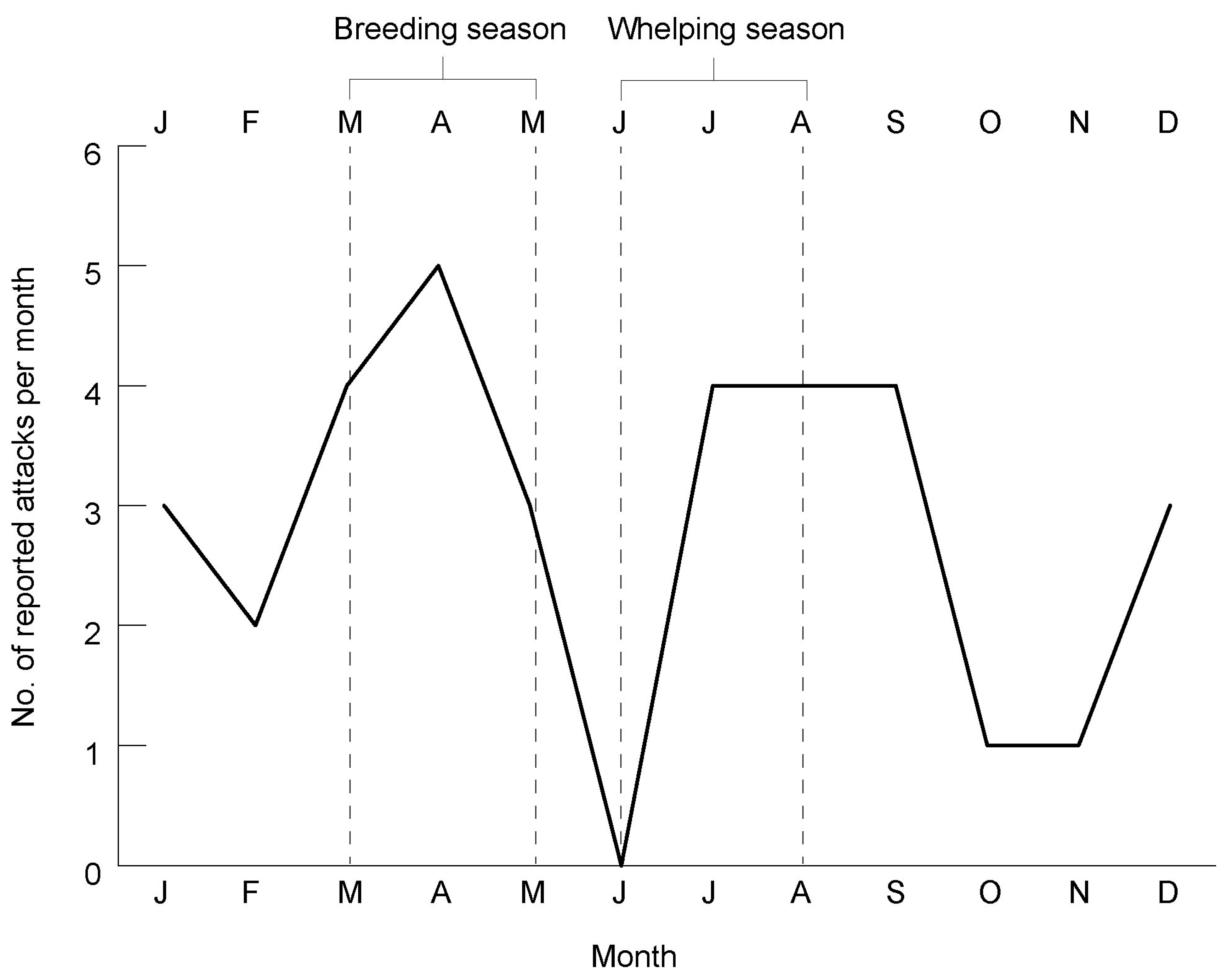

3.2. Seasonality of Attacks

3.3. Habituation and Food-Conditioning as a ‘Modern’ Phenomenon

4. Results: Earlier Cultural Attitudes towards Dingoes

5. Discussion

5.1. What Caused This Transformation?

5.2. Development of the ‘Deadly Dingo’ Trope

5.3. Rise of the Popular Belief That Dingoes Do Not Prey on People

In certain locations on the mainland, almost two centuries of artificial selection pressure from lethal control practices has undoubtedly led to a skew in some resident populations in relation to responses to human stimuli, away from boldness and towards something suggestive of a fear response[17] (p. 141)

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Chamberlain Case

As soon as I reached the front of the tent, I could see the blankets scattered. Instinct told me that she wasn’t there, the dog had her, but my head told me it wasn’t possible. Dingoes don’t do such things, and this was, you know, just beyond the realms of reason[6] (p. 155)

Appendix B. Human–Dingo Conflict on K’gari

Appendix C. The Disappearance of Willie Gesch

Appendix D. Historical Accounts of Dingo Attacks

Appendix E. Cultural Attitudes towards Dingoes in Australian History

Appendix E.1. Pre-Early 20th Century Perceptions of Dingoes and Human–Dingo Interaction

He said that one night when he was out by himself the [native] dogs would pull at his hair and then travel round him and try to pull off his boots. I began to be a bit afraid, and felt scared, as I had been told about them devouring men and worrying them, sometimes eating part of them and then leaving them, at a place named Frederick’s Valley, near Orange[207] (p. 10)

What was she to do? She could not fight them, single handed, and neither could she turn away from them, for they would soon overtake her and then attack her. My intrepid granny ran to the nearest tall tree and climbed to the highest branch. The enraged dingoes were by now at the foot of the tree, howling and springing upwards; but granny was just out of their reach[214] (p. 6)

He told me of many ups and downsOn this dreary track at night,When the native dogs like packs of hounds,Had attacked him left and right[216] (p. 3)

In fancy I hear his last terrified cry,As he wakens to catch the wild dingoe’s [sic] eyes.Sometimes death’s a blessing and so it was here,For it ended all sufferings, dispelled all fear…[217] (p. 4)

Wrap me up with my stockwhip and blanket,And bury me deep down below,Where the dingoes and crows can’t molest me,In the shade where the coolibahs grow[225] (p. 66)

Hark! there’s the wail of a dingo,Watchful and weird—I must go,For it tolls the death-knell of the stockmanFrom the gloom of the scrub down below[225] (p. 67)

Appendix E.2. A Shift in Thinking in the Early 20th Century

Mr. Norman Bourke, president of the United Graziers’ Association, said he knew the habits of dingoes very well, but he had never heard of a case of human beings being attacked by the dogs. It was a million to one chance against it[128] (p. 16)

Appendix F. Urban Wild Dingoes

| Year | Month/Day | Location | Age (in Years) of Person Involved | Number of Dingoes Involved | Description of Incident | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1804 | ~8 July | Prospect, Parramatta district (NSW) | 2–3 | Unkn. | The Sydney Gazette of 22 July 1804 described the recent death of a toddler who had wandered away from the family farm and was not missed by his mother until the following day; ‘when being given to understand the infant had not been seen by any one, she rushed into the Bush attended by several friends and neighbours, and about three miles distant from the house near to a pool of water, found the scattered remains of the boy, whose body had apparently become a prey to native dogs, and was more than half devoured’ [191] (p. 2). In a subsequent report on this case, however, published 5 August, the Sydney Gazette recanted the dingo theory: ‘The report that prevailed about Parramatta, and by which we were misled, stating that the unfortunate infant that strayed from Prospect had been partly devoured by native dogs, was unfounded; but we are extremely sorry to learn that the only fallibility of that account consisted in the circumstances of its death: The body of the little creature having been last week found at the verge of a pond in the neighbourhood of Toongabbee [Toongabbie], where it had doubtless perished through fatigue and want’ [192] (p. 2). No further details about this incident have been forthcoming. | [191,192] |

| 1805 | February | Botany Bay (NSW) | Adult | 2 | According to a florid account in the Sydney Gazette, an unnamed man claimed he was attacked by a pair of dingoes while walking alone in the Bush near the Botany Bay settlement. He hurriedly climbed a tree to escape. The dingoes, ‘after imposing an embargo of seven or eight hours by their vexatious presence, at daylight forsook their prisoner to a train of unenviable reflections’ [275] (p. 8). | [275] |

| 1815 | August | Nepean district (NSW) | 2 | Unkn. | The two-year-old daughter of John and Ann Andrews (the child’s name was omitted from the contemporary reports) disappeared from the family’s farm on 11 August 1815; no trace of her was found after an initial search of the surrounding bushland, leading to the presumption that she had been ‘carried off by native dogs’ [276] (p. 2). A subsequent report stated that her body was found 17 days later ‘in an almost impenetrable scrub, at the distance of a mile and a half from the spot where she had been last seen. A part of the body had been devoured, apparently by native dogs, by which it was most probable the unfortunate child had been drawn into the scrub, after a death from cold or famine’ [277] (p. 2). The Sydney Gazette contained reports of dingoes causing widespread stock destruction in the Nepean settlement in 1814 [79]. | [276,277] |

| 1836 | Unkn. | K’gari (Qld) | Adult (23 years of age) | 1 | British castaway John Baxter reportedly claimed that while shipwrecked on the island of K’gari in 1836: ‘He was … attacked and bitten by a wild (dingo)’ [166] (p. 66). No further details are available, and no insight was offered at the time into the dingo’s motivation. | [166] |

| 1841 | August or September | Namoi River (NSW) | ~3 | Unkn. | The three-year-old child (unknown sex) of Patrick Taigh, a stockman or shepherd at the Namoi River Station, disappeared in the Bush. The searchers concluded that the child was ‘devoured by the native dogs’ [278] (p. 3). | [278] |

| 1843 | February | Hunter River district (NSW) | ~2 | Unkn. | A small boy, first name unknown, son of clearing leaser James Gill, went missing from his family’s home in the Bush close to a nearby township. His tracks could be traced for some distance, but his body was never found; ‘There are divers [sic] opinions as to the manner in which the child met its end, some supposing that native dogs have destroyed it’ [279] (p. 2). | [279] |

| 1844 | Unkn. | Wollombi area, Hunter Valley (NSW) | Adult | ~12 | In a colourful first-hand account, a writer claimed that while on a solo hunting trip in remote bushland he or she was attacked one evening by about a dozen dingoes, which surrounded them snarling and snapping. The writer escaped the dingoes by climbing a tree that had fallen at an angle against another. One of the dingoes tried to follow the person up the tree, so they shot it, and then fired again into their midst. At this time the writer’s hunting dog came to their aid, and, after another shot, the dingoes retreated. | [227] |

| 1844 | ~November | Melbourne area (Vic) | Adult | Unkn. | A man named Guise rode his horse into the Bush while suffering the effects of advanced alcoholism, and disappeared. His body was found later, partly eaten by dingoes. The assumption was that in his incapacitated state he had been killed and partially consumed by dingoes. | [280] |

| ~1845 | Unkn. | Mount Tennant, Tharwa (ACT) | ~12 | Unkn. | A fatal dingo attack was supposed to have taken place in about 1845 near Mount Tennant, Tharwa. Details of the case were preserved for decades in the oral history of the local rural community prior to being published for the first time by Canberra journalist John Gale (1831–1929), an early resident of the Queanbeyan-Canberra area, and pastoralist Samuel Shumack (1850–1940). The written accounts of Gale [281] (p. 112) and Shumack [106] (p. 123) suggested that an unnamed 12-year-old girl, daughter of a family that worked on Cuppacumbalong station, ran away from home following a disagreement. While hiding in the scrub overnight she was reportedly attacked, killed, and partly eaten by dingoes. Her remains were found the next morning. No newspaper articles or other contemporary accounts that referred to this incident have been identified. | [106] (p. 123); [281] (p. 112) |

| ~1850 | Unkn. | Para River (SA) | Adult | ~20 | An unnamed shepherds’ hutkeeper, travelling on foot at night, and carrying a large side of mutton, was surrounded by a group of around 20 dingoes. The dingoes were ‘howling and snapping about him, but still keeping out of reach’ [81] (p. 10). His ‘screams of terror’ brought assistance from three men in the nearby homestead, who rode up with dogs and drove away the dingoes [81] (p. 10). | [81] |

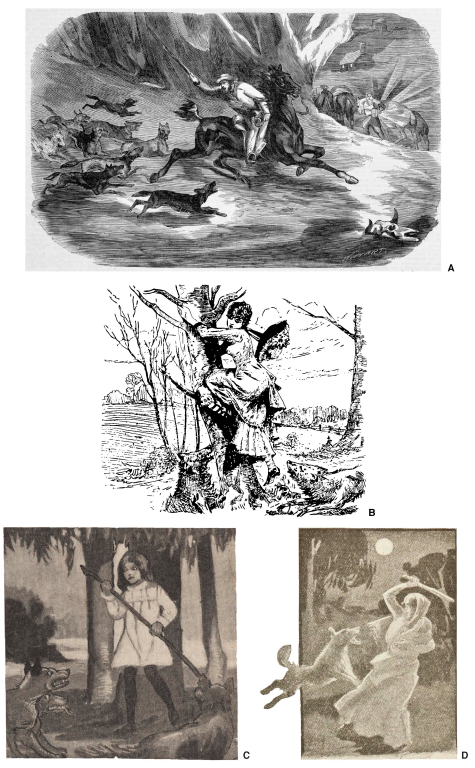

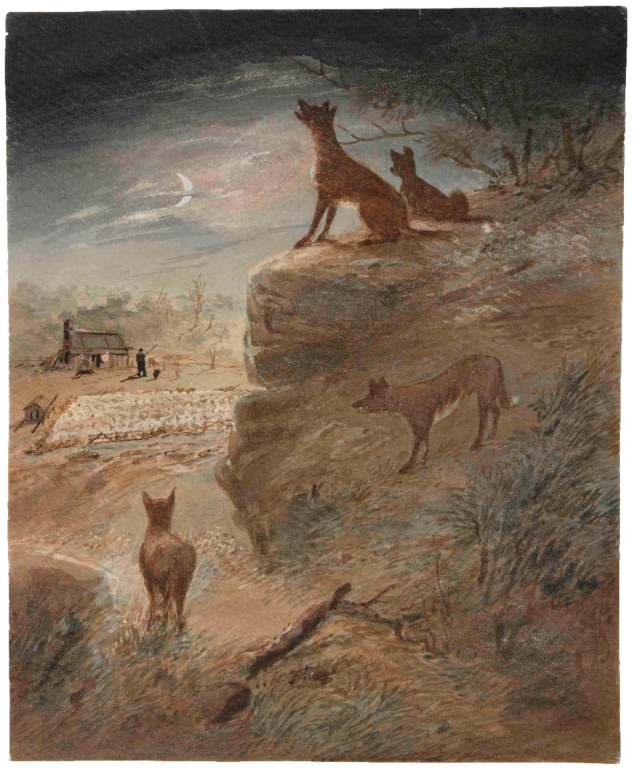

| ~1850 | Unkn. | Para River (SA) | Adult | M/P | A mounted rider, Mr. William Grey, was ‘pursued by a large pack of wild native dogs, and had to fly for his life’ [81] (p. 10). See Figure A1 for a contemporary illustration of this event. | [81] |

| 1850 | March/April | Coonabarabran (NSW) | ~5 | Unkn. | An unnamed five-year-old child, daughter of shepherd Peter Standley, lost in the Bush at Marian Park Station, was found dead, with her frock and bonnet nearby, after a period of 10 days. The ‘mutilated bones’ were in a state consistent with the child having been ‘devoured by native dogs’ [282] (p. 2). | [282] |

| 1850 | January/February | Molong Creek, Bathurst district (Vic) | Adult | Unkn. | The body of sawyer Thomas Farrell, described as having had a serious drinking problem, was found in the Bush partly eaten by dingoes. It was assumed at the time that the animals had attacked and killed him while he was incapacitated by strong liquor. | [283] |

| 1851 | October | Mount Gambier (SA) | ~3 | Unkn. | According to a report in the Argus, entitled ‘Melancholy loss of a child’, the three-year-old son of Mr. Grant ‘strayed from his father’s house, and perished in the bush, he was nearly all devoured by the native dogs’ [284] (p. 2). | [284] |

| 1851 | December | Bathurst district (NSW) | ~2 | Unkn. | A toddler (name and sex not provided), apparently the child of a shepherd, left the family’s hut on a sheep station and disappeared in the Bush; ‘The heart-rending conclusion is that the infant has been devoured by the native dogs’ [285] (p. 3). | [285] |

| 1864 | August | Queanbeyan (ACT) | Adult | Unkn. | A shepherd, name unknown, went missing in the Bush without a trace: ‘It is presumed that the unfortunate man, who was given to drink, had in a fit of drunkenness either wandered and lost himself, or in his helpless and unconscious state been attacked and devoured by native dogs’ [286] (p. 2). | [286] |

| 1867 | January | Muswellbrook, Upper Hunter region (NSW) | 4 | Unkn. | The young child (unnamed, sex not given) of Charles Laurence, a shepherd on Ravensworth Station, Sandy Creek, disappeared in the Bush, and ‘it is feared it has been devoured by native dogs’ [287] (p. 24). | [287] |

| 1870 | Unkn. | Oyster Harbour (WA) | Adult | Unkn. | According to a brief newspaper report, the skeletal remains of John Doggett were found in the scrub: ‘It is supposed that the native dogs dragged him up in the bush and devoured him’ [288] (p. 2). | [288] |

| Pre-1872 | Unkn. | ‘Medindi’ (probably Menindee) district, Darling River (NSW) | Adult | Unkn. | A drover on Pammamera cattle station related a story about an unnamed woman who was reportedly killed and eaten by a dingo (or dingoes) on the property. One of the animals was supposedly found ‘in a choking condition, his mouth and throat full of the luxuriant tresses of their late victim’ [289] (pp. 16–17). No further information has been forthcoming about this account, which, prior to this written record, possibly only existed in the oral history of the station workers and wider rural community. | [289] |

| 1875 | 13 March | Murrumburrah (NSW) | Adult | 3 | A cattleman (a Mr. Barnes) was engaged in looking after his stock when ‘he was suddenly attacked by three half-bred dingoes, which tore his trousers, and inflicted a severe wound on one of his legs. He managed to beat them off, and mounting his horse rode away from the savage mongrels, glad to escape without further treatment from their fangs’ [290] (p. 5). Given the early context these canids are unlikely to have been ‘half-bred’ domestic dog/dingo crosses but rather pure dingoes or hybrids with dominant dingo ancestry (see, e.g., [261]). | [290] |

| 1876 | 17 September | Thompson’s Swamp (NSW) | Children and adults | M/P | Two lads were attacked at night in the Bush by dingoes. They climbed a tree to safety. Inspector Lloyd and police trooper Amies, and various patrons from a nearby pub, came to their assistance and were themselves attacked. According to one, ‘I felt myself bitten in the hand, and turning instantly I saw the brute six feet from me, and before I had time to defend myself in any way, he sprang at me a second time, biting me on the thigh’ [229] (p. 4). The policemen fired on the dingoes, killing one and wounding another. The other dingoes retreated. | [229] |

| 1876 | 4 May | Maryborough district (Qld) | Adult | 1 | A settler woman was aggressively confronted by a dingo that had been raiding her farm for poultry. | [291] |

| 1879 | April | Fassifern Scrub [present-day Kalbar], (Qld) | 5 | Unkn. | The young child (Herman, or Hermann, Gerchow) of a German settler was lost in the scrub in the Fassifern area on 15 April 1879. A search was conducted over six days, but he was never found; ‘The general opinion in the neighbourhood is that the child has been devoured by native dogs, which abound in the scrub’ [292] (p. 2). | [292] |

| 1880 | 14 December | Munna Creek, Miva (Qld) | 2 | Unkn. | A two-year-old boy, Willie Gesch, disappeared from the verandah of the family’s home on a Munna Creek selection, after being left unsupervised by his mother for about 10 min. No traces of the child were found. According to contemporary newspaper reportage, his parents believed that dingoes seen prowling around the Gesch selection on the day of his disappearance had seized Willie from the verandah and dragged him away into the Bush and eaten him. See Appendix C for a detailed discussion. | [174,175] |

| ~1881 | Unkn. | Mount Drummond (SA) | Adult | ~20 | A writer claimed that while camping alone in remote bushland he or she was surrounded at night by a pack of up to 20 dingoes. They made a large fire and kept it going all night to keep them away. The dingoes made repeated rushes at him/her, causing he/her to jump up shouting and waving firebrands at them. | [208] |

| 1883 | April/May | Kanyaka district, Mount Gambier (SA) | 2.5 | Unkn. | James ‘Jimmy’ Bole, the young son (aged 2.5 years) of a farmer, went missing in the Bush. A search was conducted by Aboriginal trackers and over 50 horsemen. After days of fruitless searching the police concluded that ‘he must have been devoured by the wild dogs, which are very numerous in that part of the country, which is about the roughest in the district, and the small size of the boy … would present no obstacle to his being dragged into one of the holes where the dogs kennel and all trace of him be lost’ [293] (p. 5). Decades later it was reported that long after the search had been abandoned his remains were found in a mountain gully, alongside the cricket bat he had been carrying when he went missing [294]. | [293,294] |

| 1884 | Unkn. | Arangba, Gayndah district (Qld) | Adult | Unkn. | The partly eaten remains of a Chinese man were found in the Bush, purportedly next to some opium and an opium pipe. The latter items, if they existed, clearly satisfied the prejudiced view of Chinese settlers as depraved opium addicts [107], leading to the conclusion that dingoes had attacked the man while he was under the effects of the drug. | [295] |

| 1884 | Unkn. | Dawson River (Qld) | Adult | 2 | It was claimed, in a ‘Fifty years ago’ section of the Maryborough Chronicle, that in 1884 a young cattlewoman tried to rescue some cattle from a dingo attack and was set upon by the animals, climbing a tree to escape [296] (p. 2). See Figure A1. | [296] |

| 1885 | July | Bundaberg area (Qld) | 3 | Unkn. | A young child was lost in the Bush without a trace; ‘The police have gone in search, but it is feared the dingoes have done their work with the child’ [35] (p. 3). | [35] |

| 1887 | September | Carew, Tatiara region (SA) | 3.5 | Unkn. | A toddler, Thomas Carson, wandered away from his home on 2 September 1887 and vanished in the Bush. Contemporary newspaper reports did not mention the possibility that dingoes were involved in his death [297]. However, a letter written to the Chronicle on 24 March 1932, apparently from a family member, stated that ‘Being on the edge of the Ninety Mile Desert, which was infested with dingoes, it is the opinion of old bushmen that he was devoured by wild dogs’ [298] (p. 2). | [297,298] |

| 1888 | April | Saddler’s Creek (NSW) | Adult | M/P | The caretaker of a station at Saddler’s Creek, a man named Moran, ‘while walking through one of the station paddocks was ferociously attacked by a mob of native dogs’ [299] (p. 13). | [299] |

| 1889 | Possibly April | Carpendeit, Heytesbury forest (Vic) | Adult | M/P | A man was skinning a bullock in a paddock when a pack of dingoes approached him in a threatening manner. His sheepdog took on the dingoes and was quickly killed. The man fled. | [300] |

| ~1889 | Unkn. | Queensland | Adult | 6 | A swaggie (itinerant Bush labourer) who made a solitary journey on foot from Melbourne to the far north of Queensland recalled being attacked by dingoes while camped alone in the Bush: ‘One night when I was in the act of preparing a [johnny-]cake, after lighting a large fire for ashes, six dingoes came and took possession of the camp. I was obliged to retire, and leave them to devour all my flour and a piece of salt meat I had in my tucker bag. They showed their teeth freely, and growled rather more than was pleasant. I took a long stick of ironbark, set fire to one end of it, and warded them off by thrusting it against their noses. They followed me over three miles, when they gradually fell behind’ [209] (p. 26). | [209] |

| 1891 | July | Budgerum, Boort district (Vic) | ~2–3 | 2 | In the 10 July edition of The Boort Standard it was reported that three days before the toddler-aged child of a selector couple momentarily strayed outside the family’s house on a remote selection and was seized and carried off into the scrub by two dingoes [193]. The child’s body was never recovered. In the 31 July edition of The Boort Standard, however, a correspondent claiming to be from the Budgerum district stated, in a perfunctory letter, that ‘such an occurrence has not happened in the district’ [194] (p. 1). No further information about this affair has been uncovered. | [193,194] |

| 1899 | May | Upper Murray (NSW) | Adult | M/P | A woman who was lost in the Bush at one stage encountered a ‘mob’ of dingoes ‘and had to take refuge in a tree’ [301] (p. 2). The dingoes crowded around the tree for several hours, snarling and snapping at her. Eventually the dingoes ran off in pursuit of some wallabies, providing an opportunity for the woman to escape. | [301] |

| 1901 | July | Maryborough district (Qld) | ~10 | 1 | A young farm boy, George Emery, had been followed by a dingo for three evenings in succession when out milking cows, and ‘On the third evening the dingo made a violent attack, and the little fellow had a very narrow escape, but as it was a very rocky creek, the boy managed to get over to the other side of the creek, and as stones were plentiful he kept the savage animal at bay’ [302] (p. 3). A police search for the dingo responsible for the attack uncovered a nearby denning site with pups and adult dingoes present. | [302] |

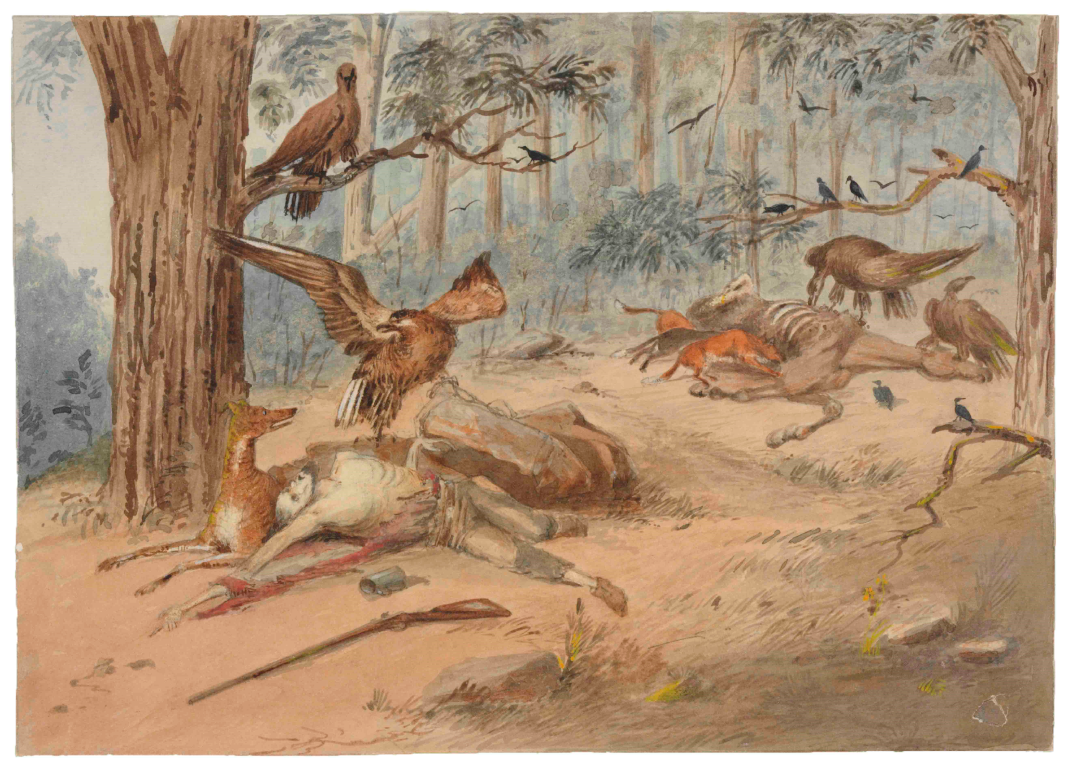

| 1902 | Late April/early May | Gammon Ranges (SA) | Adult | M/P | An article in The Port Augusta Dispatch reported that an elderly male prospector named Harry Hemming, who was ‘somewhat feeble and near sighted’, was missing for several weeks in a remote part of the Gammon Ranges, where ‘The surrounding country is very mountainous and ragged and abounding in native dogs’ [303] (p. 3). Aboriginal trackers eventually led a police search party to Hemming’s body in a valley below a high ridge on which the prospector had been camping. Hemming had been ‘almost totally devoured’ by dingoes [303] (p. 3). The old man had supposedly fallen from an adjacent precipice into the valley below. The article claimed that Hemming’s thigh was broken during the fall, and he sustained other incapacitating injuries. He had survived for long enough, however, to remove his belt and singlet and place them on a rock. The newspaper article also stated that: ‘The trackers express the opinion that the (dingoes) attacked him on top of the hill and in his endeavour to get down the cliff for protection, lost his footing and fell’ [303] (p. 3). The police report on the search for Harry Hemming is held in the State Records of South Australia [304]. Dated 31 May 1902 and written by the constable in charge of the search, R.G. (Robert Gibson) Birt from Beltana Police Station, it confirms the accuracy of some of the information in the newspaper article [304]. Birt’s report comprises a four page hand-written document, almost all of which was devoted to explaining the history and complex logistics of the search for Hemming (including an initial foray that was abandoned owing to the unexpectedly difficult terrain) and the hardships the party faced in the rough Bush country, presumably to justify to his superior the time and expense devoted to the long expedition and to emphasise the remarkable achievement it yielded (an outcome Birt attributed to the superb skills of the Aboriginal trackers, ‘Claypan George’, ‘Bennie’, ‘Bobbie’ and ‘Walter’, which he unstintingly praised). Scant detail (~9 of 132 lines, with 5–7 words per line) was devoted to a description of Hemming’s body and its context, the ‘crime scene’, and supposition as to cause of death [304]. Birt noted simply that it appeared to him the prospector had accidentally fallen to his death at some stage between the 16th and 18th of April, and that dingoes had eaten all of the flesh from his body. (The search party buried Hemming’s body on the spot and placed rocks over the simple Bush grave to protect it from scavenging dingoes [304]). The report does not contain any mention of the theory attributed to the trackers in The Port Augusta Dispatch [303] that dingoes had attacked Hemming at his camp, so either this part of the newspaper story was an embellishment or the trackers’ theory was omitted from Birt’s report. The Australian author Ion ‘Jack’ Idriess wrote (possibly with Birt’s involvement) an account of the search for Harry Hemming in his 1946 book Man Tracks [305] (pp. 86–114), but the dingo attack theory was not mentioned. | [303,304] |

| 1906 | March | Murwillumbah area (NSW) | 2 | Unkn. | A two-year-old child, surname Hitchens, was lost in the Bush: ‘The child has not been heard of since, and it is thought has made its way into the river and been drowned, or been taken by dingoes’ [306] (p. 2). | [306] |

| Pre-1907 | Unkn. | Granville/Parramatta district (NSW) | Adult | M/P | Referring to ‘The red road which joins the Southern and Western roads at Granville (known as the Dog-trap Road)’, a Sydney resident wrote: ‘It is not so many years since a pack of dingoes attacked a butcher’s cart loaded with sides of beef, on this road; the driver and horse only escaped by the skin of their teeth’ [66] (p. 10). | [66] |

| 1909 | ~September | Clifton district, Illawarra (NSW) | Adult | M/P | A Clifton miner, John Pallier, searching for wild Bush flowers, was lost in the thick scrub on the Illawarra escarpment. According to the Singleton Argus: ‘A pack of dingoes attacked Pallier, forcing him to seek refuge in the branches of a tree, where he sat the whole night’ [307] (p. 6). Eventually the dingoes appeared to disperse. The following day, after Pallier had fallen out of the tree, he kept wandering, but the dingoes continued to stalk him for two days and nights, ‘watching his movements from the shelter of the scrub’ [307] (p. 6). The miner was found alive near Coledale. | [307] |

| ~1910 | Unkn. | K’gari (Qld) | Adult | M/P | According to the oral history of Gordon Peters, who was a bullock-driver on K’gari in the early 1900s, fellow K’gari resident Christy Mathison was hunting in the scrub on the island one day when he encountered a group of dingoes comprising two adults, a subadult, and four young pups. Two other adult dingoes were nearby. According to Peters the dingoes became ‘very agitated and then aggressive’ [162] (p. 163). Sensing an attack was imminent, Mathison ran away and hid in the root structure of a fig tree. Peters claimed that: ‘The dingoes came on, starting to attack, so Christy aimed his double-barrel shotgun out between the roots and managed to shoot five of the nine dingoes. The other four escaped into the bush’ [162] (p. 163). | [162] |

| 1912 | ~18 August | Booyal, Bundaberg district (Qld) | 4 | Unkn. | A four-year-old boy, Harold Halliday, lost in the scrub at Booyal on 18 August, ‘has been killed and eaten by the wild dogs which infest the locality’, according to police findings [308] (p. 4). The Brisbane Courier reported that: ‘Batches of young pups have been seen frequently by the search parties, many of whom share the opinion of the police’ [308] (p. 4). The search, led by an Aboriginal tracker (identified in the newspaper report only as Tommy), lasted for about a fortnight. The child’s body was never found. | [308] |

| 1916 | ~January | Daymar (Qld) | 3 | Unkn. | The remains of a three-year-old boy, Edgar Tighe, who had been lost in the Bush, were found several kilometres from his home: ‘One leg was bitten off either by foxes or dingoes. He had got over a six feet high dog proof netting fence, which surrounded the paddock where the home is situated’ [309] (p. 3). | [309] |

| 1917 | September | Pikedale (Qld) | 9 or 10 | Unkn. | A young boy, Thomas Kenny, disappeared while shepherding a flock of sheep on his own in the Bush near Pikedale. An Aboriginal tracker identified the boy’s tracks near his father’s hut, from where he had initially set out, but no further traces of him were found. It was assumed at the time he was ‘eaten by native dogs’ [310] (p. 7). | [310] |

| 1924 | Unkn. | K’gari (Qld) | Adult | M/P | The lighthouse-keeper at Inskip Point was reportedly ‘chased from the beach where he had been fishing by a number of fierce (wild dingoes)’ [167] (p. 6). | [167] |

| Pre-1924 | Unkn. | Braidwood district (NSW) | Adult | 1 | According to one source [231], an unnamed elderly Chinese man was walking alone at night when he noticed an ‘old man’ dingo following him. Frightened, he broke into a run and was immediately set upon and attacked by the animal. The man yelled in fright and some people came to his aid, scaring away the dingo. A correspondent to the Bulletin provided an earlier version of this story in 1924 [311]. This writer claimed that the man had noticed the presence of several ‘warrigals’ (dingoes) around his hut in the days leading up to the incident [311] (p. 24). It was said that he was on his way to a creek when he was set upon by three dingoes. One dingo succeeded in seizing him by the throat before he beat them off with a bucket and barricaded himself in his hut [311]. | [231,311] |

| 1925 | Unkn. | Kilcoy, Mollman’s Scrub (Qld) | 10.5 | M/P | A young boy, Neil Barnett, out looking for a horse on foot, was ‘confronted by a dingo, which made at [sic] attempt to attack him’ [312] (p. 4). A pack then surrounded him. He picked up a stick to defend himself, but then decided to climb a tree for safety. The dingoes then attacked a nearby calf, so the boy ‘jumped from the tree and belted the dingoes off’ [312] (p. 4). | [312] |

| 1925 | March | Hampden, Mackay district (Qld) | 2.5 | Unkn. | On 19 March, the Maryborough Chronicle reported that the remains of a toddler, John Henry O’Sullivan, aged 2.5 years, still had not been found after extensive searching. His parents were selectors who owned a small block at Hampden. His mother had been in the Bush alone with him and his younger sibling, mustering cattle, when Henry wandered off unnoticed. The police concluded he had been taken by dingoes or a wedge-tailed eagle. | [93] |

| Pre-1927 | Unkn. | North coast district (NSW) | Child | 1 | An unnamed ‘farm lad’ was ‘set upon’ by a dingo, which ‘bolted as soon as he screamed with fear’ [231] (p. 18). | [231] |

| 1927 | Unkn. | Paterson (lower Hunter region of NSW) | Youth | 5 | A ‘youth’, R.S. Kidd, was riding in the Bush when he observed a pack of five dingoes attacking a cattle dog. He intervened in an attempt to save the dog, ‘shooing’ away the dingoes, but was attacked and sustained a serious injury to his leg. He managed to ‘beat them off with a stick’ [313] (p. 6). The dog was killed. | [313] |

| 1927 | 12 December | Nambour district (Qld) | Child | 4 | A shepherd’s son (surname Lowe) went to look for some sheep that had got out of a fenced dingo-proof enclosure. He found one of the sheep dead in a gully, with four or five dingoes nearby. He tried to frighten the dingoes away by rushing at them, shouting and throwing a stone. One ran away, but the others ‘made a rush for the boy’, prompting him to scream loudly with fright [314] (p. 3). His brothers and a neighbour came to his aid, ‘and there found the dingoes attacking him. The brutes had torn his shirt to ribbons, but fortunately, had not hurt the flesh. It is considered that the lad had a narrow escape’ [314] (p. 3). | [314] |

| 1928 | 27 May | Merewether (now a suburb of Newcastle) (NSW) | Adult | M/P | A man named George Cox was returning home on foot from a fishing excursion when he was surrounded and ‘attacked by a pack of hungry dingoes’ [315] (p. 4). He struck the nearest dingo with a stick, but the others closed in on him. Cox climbed the nearest tree and remained there until early morning; ‘All through the night the dingoes made wild leaps at his feet and then early in the morning ran off into the bush’ [315] (p. 4). A search party found him in the scrub at 3 a.m.; ‘They reached the tree where he had taken refuge when seven dingoes returned and attacked the defenceless men. There followed a furious fight in which Cox joined and eventually one of the beasts was killed, and the rest made off. Cox reached home in a state of collapse’ [315] (p. 4). | [315] |

References

- Corbett, L.K. The Dingo in Australia and Asia; Comstock: Ithaca, NY, USA; Cornell: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Balme, J.; O’Connor, S.; Fallon, S. New dates on dingo bones from Madura Cave provide oldest firm evidence for arrival of the species in Australia. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.P.; Savolainen, P. The origin and ancestry of the dingo. In The Dingo Debate: Origins, Behaviour and Conservation; Smith, B.P., Ed.; CSIRO Publishing: Clayton South, Australia, 2015; pp. 55–79. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard, J.W.O.; Wilson, L.A.B. The Australian dingo: Untamed or feral? Front. Zool. 2019, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koungoulos, L. Domestication through dingo eyes: An Australian perspective on human-canid interactions leading to the earliest dogs. Hum. Ecol. 2021, 49, 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, J. Evil Angels: The Case of Lindy Chamberlain; Summit Books: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Craik, J. The Azaria Chamberlain case and questions of infanticide. Aust. J. Cult. Stud. 1987, 4, 123–151. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, J. Prisoner of discourse: The dingo, the dog and the baby. Anthropol. Today 1989, 5, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain-Creighton, L. Through My Eyes: The Autobiography of Lindy Chamberlain-Creighton; East Street Publications: Bowden, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, J. Against the tactician. In The Chamberlain Case: Nation, Law, Memory; Staines, D., Arrow, M., Biber, K., Eds.; Australian Scholarly Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2009; pp. 277–283. [Google Scholar]

- Craik, J. The Azaria Chamberlain case: Blind spot or black hole in Australian cultural memory. In The Chamberlain Case: Nation, Law, Memory; Staines, D., Arrow, M., Biber, K., Eds.; Australian Scholarly Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2009; pp. 268–276. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain, M. Heart of Stone: Justice for Azaria; New Holland Publishers Pty Ltd.: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, J. The myths of Azaria, so many: Superstition ain’t the way. Griffith Rev. 2013, 42, 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Middleweek, B. Dingo media? The persistence of the “trial by media” frame in popular, media, and academic evaluations of the Azaria Chamberlain case. Fem. Media Stud. 2017, 17, 392–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleweek, B. Feral Media? The Chamberlain Case, 40 Years on; Australian Scholarly Publishing Ltd.: Melbourne, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham, A. Chamberlain: A retrospective. Vic. Bar News 2020, 168, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Appleby, R. Dingo-human conflict: Attacks on humans. In The Dingo Debate: Origins, Behaviour and Conservation; Smith, B.P., Ed.; CSIRO Publishing: Clayton South, Australia, 2015; pp. 131–158. [Google Scholar]

- Appleby, R.; Mackie, J.; Smith, B.; Bernede, L.; Jones, D. Human-dingo interactions on Fraser Island: An analysis of serious incident reports. Aust. Mammal. 2018, 40, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.G. Changing patterns of shark attacks in Australian waters. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2011, 62, 744–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.P.; Litchfield, C.A. A review of the relationship between indigenous Australians, dingoes (Canis dingo) and domestic dogs (Canis familiaris). Anthrozoös 2009, 22, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumm, A. Dingoes and domestication. Archaeol. Ocean. 2021, 56, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tench, W. A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay with an Account of New South Wales, Its Productions, Inhabitants, &c. to Which Is Subjoined, a List of the Civil and Military Establishments at Port Jackson; J. Debrett: London, UK, 1789. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Fight with Dingo. The Macleay Chronicle, 19 August 1942; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Beier, P. Cougar attacks on humans in the United States and Canada. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 1991, 19, 403–412. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, R.L. Alligator attacks on humans in the United States. Wilderness Environ. Med. 2005, 16, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, L.A.; Gehrt, S.D. Coyote attacks on humans in the United States and Canada. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2009, 14, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Do, Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Cowan, P.; Joo, G.-J. Conservation activities for the Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra) in South Korea traced from newspapers during 1962–2010. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 210, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacs, V.; Kirkpatrick, R. Two Hundred Years of Sydney Newspapers: A Short History; Rural Press Ltd.: North Richmond, Australia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, H. The Press in Australia; Lansdowne Press Pty. Ltd.: Melbourne, Australia, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, R.B. The Newspaper Press in New South Wales, 1803–1920; Sydney University Press: Sydney, Australia, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Ingleton, G.C. True Patriots All, or News from Early Australia—As Told in a Collection of Broadsides, Garnered & Decorated by Geoffrey Chapman Ingleton; Angus & Robertson: Sydney, Australia, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Flanders, O. When Dingoes ‘Attack’: A Look at Human-Dingo Interactions as Reported by the Media. Unpublished. Bachelor of Psychological Science (Honours) Thesis, Central Queensland University, Rockhampton, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, T. ‘Recollections of Thomas Davis’ Collected by Steele Rudd. Unpublished Manuscript. Fryer Library, University of Queensland: Brisbane, Australia, (UQFL79-Series F-Subseries 2-File 3), n.d. (created 1908–1909).

- de Looper, M.W. Death Registration and Mortality Trends in Australia 1856–1906. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Bundaberg. Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser, 28 July 1885; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Koungoulos, L.; Fillios, M. Between ethnography and prehistory: The case of the Australian dingo. In Dogs: Archaeology Beyond Domestication; Bethke, B., Burtt, A., Eds.; University Press of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 206–231. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, B.L.; Higginbottom, K.; Bracks, J.H.; Davies, N.; Baxter, G.S. Balancing dingo conservation with human safety on Fraser Island: The numerical and demographic effects of humane destruction of dingoes. Australas. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 22, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, G.C.; Lamont, R.W.; Bridges, L.; Stephens, D.; Wardell; Johnson, A.; Ogbourne, S.M. Conservation concerns associated with low genetic diversity for K’gari–Fraser Island dingoes. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, D.; Wilton, A.N.P.; Fleming, J.S.; Berry, O. Death by sex in an Australian icon: A continent-wide survey reveals extensive hybridization between dingoes and domestic dogs. Mol. Ecol. 2015, 24, 5643–5656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupprecht, C.E.; Freuling, C.M.; Mani, R.S.; Palacios, C.; Sabeta, C.T.; Ward, M. A history of rabies—The foundation for global canine rabies elimination. In Rabies; Fooks, A.R., Jackson, A.C., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Linnell, J.D.C.; Andersen, R.; Andersone, Z.; Balciauskas, L.; Blanco, J.C.; Boitani, L.; Brainerd, S.; Beitenmoser, U.; Kojola, I.; Liberg, O.; et al. The fear of wolves: A review of wolfs attacks on humans. NINA Oppdragsmeld. 2002, 731, 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, C. Tourist Tells of Dingo Attack. Sunshine Coast Daily, 1 August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lennox, R. Dingo Bold: The Life and Death of K’gari Dingoes; Sydney University Press: Sydney, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, K. Fraser Island Dingoes Not to Blame Says Paramedic. Brisbane Times, 14 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Dingoes Are Dangerous. MOONBI, 91, 20 April 1997; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Commission of Inquiry into Chamberlain Convictions. Report of the Commissioner the Hon. Mr. Justice T.R. Morling; Govt. Printers: Canberra, Australia, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Catling, P.C. Seasonal variation in plasma testosterone and the testis in captive male dingoes, Canis familiaris dingo. Aust. J. Zool. 1979, 27, 939–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breckwoldt, R. A Very Elegant Animal the Dingo; Angus & Robertson: North Ryde, Australia, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, P.C. The behavioural ecology of dingoes in north-western Australia: II. Activity patterns, breeding season and pup rearing. Wildl. Res. 1992, 19, 519–530. [Google Scholar]

- Purcell, B. Dingo; CSIRO Publishing: Collingwood, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.P. Biology and behaviour of the dingo. In The Dingo Debate: Origins, Behaviour and Conservation; Smith, B.P., Ed.; CSIRO Publishing: Clayton South, Australia, 2015; pp. 25–53. [Google Scholar]

- Cursino, M.; Harriott, S.L.; Allen, B.L.; Gentle, M.; Leung, L.K.-P. Do female dingo–dog hybrids breed like dingoes or dogs? Aust. J. Zool. 2017, 65, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, A.J.; Cairns, K.M.; Kaplan, G.; Healy, E. Managing dingoes on Fraser Island: Culling, conflict, and an alternative. Pac. Conserv. Biol. 2017, 23, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, B. Skin and bone: Observations of dingo scavenging during a chronic food shortage. Aust. Mammal. 2010, 32, 207–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, J.B. Seven Years in the Australian Bush; Wm. Potter: Liverpool, UK, 1880. [Google Scholar]

- Tenterfield. The Dingo. Sydney Mail, 24 June 1914; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Dingo Pack Attacks Good Samaritan. The Advertiser, 27 May 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon, M. Car Crash Survivor Attacked by Dingo. NT News, 20 June 2013; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Robson v Territory Insurance Office. Northern Territory Supreme Court (NTSC) 27. File No: M4 of 2012 (21227434); Robson v Territory Insurance Office: Darwin, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Postscript. The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 2 September 1804; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Culture of Hops in Great Britain. The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 17 March 1805; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Sydney. The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 4 November 1804; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Sydney. The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 3 July 1808; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Native Dogs. The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 19 November 1831; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Dingoes Near Sydney. The Sydney Morning Herald, 24 December 1939; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Kaleski, R. The Noble Dingo: Further Respectfully Considered in His Downsittings, His Uprisings, and His Family Relations. The Bookfellow, 1(4), 24 January 1907; pp. 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Sydney. The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 18 August 1805; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Phillip, A. The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay with an Account of the Establishment of the Colonies of Port Jackson and Norfolk Island, Compiled from Authentic Papers, Which Have Been Obtained from the Several Departments to Which Are Added the Journals of Lieuts. Shortland, Watts, Ball and Capt. Marshall with an Account of Their New Discoveries; John Stockdale: London, UK, 1789. [Google Scholar]

- McNay, M.E. Wolf-human interactions in Alaska and Canada: A review of the case history. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2002, 30, 831–843. [Google Scholar]

- McNay, M.E.; Mooney, P.W. Attempted predation of a child by a gray wolf, Canis lupus, near Icy Bay, Alaska. Ott. Nat. 2005, 119, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Newsome, T.M.; Stephens, D.; Ballard, G.-A.; Dickman, C.R.; Fleming, P.J.S. Genetic profile of dingoes (Canis lupus dingo) and free-roaming domestic dogs (C. l. familiaris) in the Tanami Desert, Australia. Wildl. Res. 2013, 40, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, T.M.; Ballard, G.-A.; Crowther, M.S.; Fleming, P.J.S.; Dickman, C.R. Dietary niche overlap of free-roaming dingoes and domestic dogs: The role of human-provided food. J. Mammal. 2014, 95, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Smith, B.P.; Vague, A.-L. The denning behaviour of dingoes (Canis dingo) living in a human-modified environment. Aust. Mammal. 2007, 39, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warriner, J. Hefty Fine for Newcrest after Wild Dingoes Maul Woman at Pilbara Mine. ABC News, 2 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sidney, S. The Three Colonies of Australia: New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia; Their Pastures, Copper Mines, & Gold Fields; Ingram, Cooke, and Co.: London, UK, 1853. [Google Scholar]

- Philanthus. To the Printer of the Sydney Gazette. The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 18 November 1804; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, M.A. Bringing the Dingo Home: Discursive Representations of the Dingo by Aboriginal, Colonial and Contemporary Australians. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, M. The cunning dingo. Soc. Anim. 2007, 15, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. Sydney. The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 26 November 1814; 2. [Google Scholar]

- Appleby, R.G.; Smith, B.P. Do wild canids kill for fun. In Wild Animals and Leisure: Rights and Wellbeing; Carr, N., Young, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 181–209. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. The Dingo. The Australian News for Home Readers, 20 July 1866; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Death and Dingoes. Western Star and Roma Advertiser, 13 July 1929; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Macintosh, N.W.G. Trail of the dingo. The Etruscan: Staff Magazine of the Bank of New South Wales 1956, 5, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, S. The Way of the Dingo; Angus and Robertson: Sydney, Australia, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Cree, B. The Bountyhunters. Mimag (Mount Isa Mines Limited), 19(6), 1 June 1969; pp. 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rolls, E.C. They All Ran Wild: The Story of Pests on the Land in Australia; Angus and Robertson: Sydney, Australia, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Macintosh, N.W.G. The origin of the dingo: An enigma. In The Wild Canids: Their Systematics, Behavioral Ecology and Evolution; Fox, M.W., Ed.; Van Nostrand Reinhold Company: New York, NY, USA, 1975; pp. 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, I.J. Touching Magic: Deliberately Concealed Objects in Old Australian Houses and Buildings. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Newcastle, Newcastle, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Blee, J. Banshees. In Goldfields and the Gothic: A Hidden Heritage and Folklore; Waldron, D., Ed.; Australian Scholarly Publishing Pty Ltd.: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2016; pp. 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, J. The Life and Adventures of William Buckley, Thirty-Two Years a Wanderer amongst the Aborigines of the then Unexplored Country Round Port Phillip, Now the Province of Victoria; Archibald MacDougall: Hobart, Australia, 1852. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, P.M. Buckley’s bunyip. In Goldfields and the Gothic: A Hidden Heritage and Folklore; Waldron, D., Ed.; Australian Scholarly Publishing Pty Ltd.: Melbourne, Australia, 2016; pp. 181–191. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. The Missing Child. Norseman Times, 23 August 1907; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Lost in the Bush. Bororen Child Still Missing. Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser, 19 March 1925; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, J. Baby-Snatching Eagle Hoaxers Tapped into an Ancient Myth. The Globe and Mail, 23 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, J. Eagle; Reaktion Books: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, J. Australian Aborigines: The Languages and Customs of Several Tribes of Aborigines in the Western District of Victoria, Australia; George Robertson: Melbourne, Australia, 1881. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, R. The Confident Years: Australia in The 1920s; Australian Scholarly Publishing Pty, Limited: Melbourne, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wood Jones, F. The status of the dingo. Trans. R. Soc. S. Aust. 1921, 45, 254–263. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, B.C.W.; Macintosh, A. The dingo—A review. Arch. Phys. Anth. Ocean. 1979, 14, 27–53. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, L.K.; Newsome, A.E. Dingo society and its maintenance: A preliminary analysis. In The Wild Canids: Their Systematics, Behavioral Ecology and Evolution; Fox, M.W., Ed.; Van Nostrand Reinhold Company: New York, NY, USA, 1975; pp. 369–378. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, P.; Corbett, L.; Harden, R.; Thomson, P. Managing the Impacts of Dingoes and Other Wild Dogs; Bureau of Rural Sciences: Canberra, Australia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Newsome, T.M. Makings of icons: Alan Newsome, the red kangaroo and the dingo. Hist. Rec. Aust. Sci. 2014, 25, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Coleman, J.T. Vicious: Wolves and Men in America; Yale University Press: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Linnell, J.D.C.; Alleau, J. Predators that kill humans: Myth, reality, context and the politics of wolf attacks on people. In Problematic Wildlife: A Cross-Disciplinary Approach; Angelici, F.M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Denmark, 2016; pp. 357–371. [Google Scholar]

- Gandevia, B.; Gandevia, S. Childhood mortality and its social background in the first settlement at Sydney Cove, 1788–1792. Aust. Paediat. J. 1975, 11, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumack, S. An Autobiography or Tales and Legends of Canberra Pioneers; Australian National University Press: Canberra, Australia, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse, R. The Vision Splendid: A Social and Cultural History of Rural Australia; Curtin University Books: Fremantle, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- McCalman, J.; Kippen, R. Population and health. In The Cambridge History of Australia. Volume 1: Indigenous and Colonial Australia; Bashford, A., Macintyre, S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. 294–314. [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton, M.E. The Australian Bush; J.M. Dent and Sons: London, UK, 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton, M.E. Bark House Days; Heath Cranton: London, UK, 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Torney, K. Babes in the Bush; Fremantle Arts Centre Press: Fremantle, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pickard, J. The transition from shepherding to fencing in colonial Australia. Rural Hist. 2007, 18, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gerrard, J. The interconnected histories of labour and homelessness. Labour Hist. 2017, 112, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, G.; Brodie, M. Introduction. In Struggle Country: The Rural Ideal in Twentieth Century Australia; Davidson, G., Brodie, M., Eds.; Monash University ePress: Clayton, Australia, 2005; pp. ix–xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie, M. The politics of rural nostalgia between the wars. In Struggle Country: The Rural Ideal in Twentieth Century Australia; Davidson, G., Brodie, M., Eds.; Monash University ePress: Clayton, Australia, 2005; pp. 09.1–09.13. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, P. The Azaria Chamberlain case: Reflections on Australian identity. In The Chamberlain Case: Nation, Law, Memory; Staines, D., Arrow, M., Biber, K., Eds.; Australian Scholarly Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2009; pp. 58–68. [Google Scholar]

- Letnic, M.; Koch, F. Are dingoes a trophic regulator in arid Australia? A comparison of mammal communities on either side of the dingo fence. Austral Ecol. 2010, 35, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelland, L. Holding the Line: A History of the South Australian Dog Fence Board, 1947 to 2012; Primary Industries and Regions South Australia: Adelaide, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Glen, A.S.; Short, J. The control of dingoes in New South Wales in the period 1883–1930 and its likely impact on their distribution and abundance. Aust. Zool. 2000, 31, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, B.L.; West, P. The influence of dingoes on sheep distribution in Australia. Aust. Vet. J. 2013, 91, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterhouse, R. Australian legends: Representations of the bush, 1813–1913. Aust. Hist. Stud. 2000, 31, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, R. Rural culture and Australian history: Myths and realities. Arts 2002, 24, 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, B.L.; West, P. Dingoes are a major causal factor for the decline and distribution of sheep in Australia. Aust. Vet. J. 2015, 93, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, S. The dingo dilemma. BioScience 2009, 59, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Philip, J. Representing the Dingo: An Examination of Dingo–Human Encounters in Australian Cultural and Environmental Heritage. Unpublished. Ph.D. Thesis, University of New England, Armidale, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. The Deadly Dingo. Morning Bulletin, 28 March 1925; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Newsome, T.M.; Ballard, G.-A.; Dickman, C.R.; Fleming, P.J.S.; van de Ven, R. Home range, activity and sociality of a top predator, the dingo: A test of the Resource Dispersion Hypothesis. Ecography 2013, 36, 914–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. Not Man-Killer: Australian Dingo. The Courier-Mail, 12 December 1933; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Binks, B.; Kancans, R.; Stenekes, N. Wild Dog Management 2010 to 2014. National Landholder Survey Results; Research Report; The Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences: Canberra, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Young, S.P. The Wolves of North America. Part I: Their History, Life Habits, Economic Status, and Control; The American Wildlife Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Fritts, S.H.; Stephenson, R.O.; Hayes, R.D.; Boitani, L. Wolves and humans. In Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation; Mech, L.D., Boitani, L., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2003; pp. 289–316. [Google Scholar]

- Jenness, S.E. Arctic wolf attacks scientist—A unique Canadian incident. Arctic 1985, 38, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mech, L.D. “Who’s afraid of the big bad wolf?”: Revisited. Int. Wolf 1998, 8, 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, K. Writing the wolf: Canine tales and North American environmental-literary tradition. Environ. Hist. 2011, 17, 201–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, L.; Dale, B.; Beckmen, K.; Farley, S. Findings Related to the March 2010 Fatal Wolf Attack Near Chignik Lake, Alaska; Wildlife Special Publication, ADF&G/DWC/WSP-2011-2; Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Wildlife Conservation: Palmer, AK, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 3105.0.65.001 Australian Historical Population Statistics, 2014: Table 2.1 Population, Age and sex, Australia, 30 June, 1901 Onwards. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Sanders, N. Azaria Chamberlain and popular culture. In The Chamberlain Case: Nation, Law, Memory; Staines, D., Arrow, M., Biber, K., Eds.; Australian Scholarly Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2009; pp. 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Seal, G. Dread, delusion and globalisation: From Azaria to Schapelle. In The Chamberlain Case: Nation, Law, Memory; Staines, D., Arrow, M., Biber, K., Eds.; Australian Scholarly Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2009; pp. 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, B. Urban dingoes (Canis lupus dingo and hybrids) and human hydatid disease (Echinococcus granulosus) in Queensland, Australia. In Proceedings of the 22nd Vertebrate Pest Conference; Timm, R.M., O’Brien, J.M., Eds.; University of California: Davis, CA, USA, 2006; pp. 334–338. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, B.L.; Goullet, M.; Allen, L.R.; Lisle, A.; Leung, L.K.-P. Dingoes at the doorstep: Preliminary data on the ecology of dingoes in urban areas. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 119, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, N.H. Against the odds: The fight to free Lindy Chamberlain. In The Chamberlain Case: Nation, Law, Memory; Staines, D., Arrow, M., Biber, K., Eds.; Australian Scholarly Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2009; pp. 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Biber, K. Judicial extracts. In The Chamberlain Case: Nation, Law, Memory; Staines, D., Arrow, M., Biber, K., Eds.; Australian Scholarly Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2009; pp. 113–151. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, P. The Country of Lost Children: An Australian Anxiety; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, E. Who Killed Azaria Chamberlain? The Washington Post, 22 March 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D. From fairy to witch: Imagery and myth in the Azaria case. In The Chamberlain Case: Nation, Law, Memory; Staines, D., Arrow, M., Biber, K., Eds.; Australian Scholarly Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2009; pp. 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Forensic Evidence Played No Part in Verdict—Juror: ‘Lindy Guilty on the Basis of Her Story’. The Courier Mail, 12 April 1984; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 3105.0.65.001 Australian Historical Population Statistics, 2019: Table 3.3 Population, Urban and Rural Areas, States and Territories, 30 June, 1911 Onwards. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Franklin, A. Dingoes in the Dock. New Scientist, 15 February 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, B. The trials of motherhood. In The Chamberlain Case: Nation, Law, Memory; Staines, D., Arrow, M., Biber, K., Eds.; Australian Scholarly Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2009; pp. 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, B. The Company of Dingoes: Two Decades with Our Native Dog; Australian Native Dog Conservation Society Limited: Bargo, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, T.; Willet, C.E.; Haase, B.; Wade, C.M. Genomic characterization of external morphology traits in Kelpies does not support common ancestry with the Australian dingo. Genes 2019, 10, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howe, A. Writing to Lindy—‘May I call you Lindy?’. In The Chamberlain Case: Nation, Law, Memory; Staines, D., Arrow, M., Biber, K., Eds.; Australian Scholarly Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2009; pp. 221–233. [Google Scholar]

- Fife-Yeomans, J.; Toohey, P. Azaria Chamberlain Jury Secrets. Daily Telegraph, 9 August 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Peace, A. Dingo discourse: Constructions of nature and contradictions of capital in an Australian eco-tourist location. Anthropol. Forum 2001, 11, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannery, T. Sorry, Lindy, We Should Have Known Better. The Sydney Morning Herald, 15 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Family Saves Boy from Attack by Dingoes. The Advertiser, 21 March 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Barlass, T. Father Tells: The Night a Dingo Took Our Baby. The Advertiser, 7 April 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, L. ‘A Dingo Had Him by the Back of the Neck’: Family Recalls Fraser Island Attack. The Brisbane Times, 2 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Goetze, E.; Khan, N. Toddler Bitten by Dingo on Queensland’s Fraser Island, Airlifted to Bundaberg Hospital. ABC News, 17 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, N. Dingo Bites 4yo Boy on Thigh on Fraser Island, in Second Attack in Weeks. ABC News, 4 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Marie, J. Dingoes on Fraser Island-K’gari Losing Their Natural Fear of Humans, Says Local Mayor. ABC News, 5 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, F. A History of Fraser Island: Princess K’gari’s Fraser Island; Merino Harding: Brisbane, Australia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, R. Early Days on Fraser Island: 1913–1922; GO BUSH Safaris: Gladesville, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, J. Dingos of Fraser Island. Fraser Island Defenders Organisation. 2015. Available online: https://fido.org.au/dingos-of-fraser-island/ (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Beckmann, E.; Savage, G. Evaluation of Dingo Education Strategy and Programs for Fraser Island; Report for Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service; Environmetrics: Brisbane, Australia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, J. Shipwreck of the Stirling Castle, Containing a Faithful Narrative of the Dreadful Sufferings of the Crew, and the Cruel Murder of Captain Fraser by the Savages. Also, the Horrible Barbarity of the Cannibals Inflicted upon the Captain’s Widow, Whose Unparalleled Sufferings are Stated by Herself, and Corroborated by the Other Survivors. To Which Is Added, the Narrative of the Wreck of the Charles Eaton, in the Same Latitude; George Virtue: London, UK, 1838. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. The Dingo Pest. Morning Bulletin, 7 June 1924; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Fierce Dingoes. Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser, 5 June 1924; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Starving Brutes on Fraser Island. The Farmer and Settler, 6 June 1924; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J. Trip to Fraser Island. The Telegraph, 1 January 1935; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- White, B.H. Hiking on Fraser. Variety of Experiences. Nature’s Wonderland. Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser, 14 January 1933; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, N.L. Fraser Island (Queensland). Walkabout, 8, 1 September 1942; pp. 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Fraser Is. Holiday. Maryborough Chronicle, 21 October 1950; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Local and General. Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser, 21 December 1880; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Local and General News. Gympie Times and Mary River Mining Gazette, 22 December 1880; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Miva. Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser, 1 October 1932; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Deaths. Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser, 7 November 1938; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, E.M. A Century of Settlement in the Miva District; Queensland Country Women’s Association (QCWA) Miva Branch: Miva, Australia, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Gesch, G.E. To the Editor: Gootchie History. Maryborough Chronicle, 18 March 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. ‘A Dingo Did Not Take My Brother’. The Gympie Times, 21 February 1981; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, A. Gesch Family of Miva. Unpublished Manuscript.

- Smith, B.P. The personality, behaviour and suitability of dingoes as companion animals. In The Dingo Debate: Origins, Behaviour and Conservation; Smith, B.P., Ed.; CSIRO Publishing: Clayton South, Australia, 2015; pp. 251–275. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.P. Dingo intelligence: A dingo’s brain is sharper than its teeth. In The Dingo Debate: Origins, Behaviour and Conservation; Smith, B.P., Ed.; CSIRO Publishing: Clayton South, Australia, 2015; pp. 215–249. [Google Scholar]

- Prentis, M.D. The life and death of Johnny Campbell. Aborig. Hist. 1991, 15, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. The Spirit of the Pioneers. Achievements of Mr. W. Gesch, Miva. Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser, 3 September 1938; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Torney, K. A city child lost in the bush. La Trobe Journal 2004, 74, 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. White Child among Blacks. Northern Star, 9 February 1907; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Meston, A. Mundi and Coyeen. The Bulletin, 19(942), 5 March 1898; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Kidnapped by the Blacks. The Richmond River Herald and Northern Districts Advertiser, 4 November 1898; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Behrendorff, L.; Belonje, G.; Allen, B.L. Intraspecific killing behaviour of canids: How dingoes kill dingoes. Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 30, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. Sydney. The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 22 July 1804; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Sydney. The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 5 August 1804; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Eaten Alive by Dingoes. The Boort Standard, 10 July 1891; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, P. A Disclaimer. The Boort Standard, 31 July 1891; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. No title. Mackay Mercury and South Kennedy Advertiser, 25 September 1878; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Northern News. The Brisbane Courier, 11 October 1878; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth, L. Investigating death in Moreton Bay: Coronial inquests and magisterial inquiries. Qld. Rev. 2019, 26, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.; Lewis, M.; Powles, J. The Australian mortality decline: All-cause mortality 1788–1990. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 1998, 22, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. Fatal Accident. The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 23 September 1804; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Local and Domestic. The Darling Downs Gazette and General Advertiser, 27 September 1860; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. The Lachlan. The Sydney Morning Herald, 3 August 1865; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Singular Providence. The Sydney Morning Herald, 11 September 1865; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Heroic Conduct of a Woman with Two Children Lost in the Bush. The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, 9 June 1870; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Rickard, J. Australia: A Cultural History; Monash University Publishing: Clayton, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Lost, and Supposed Death in the Bush. The Sydney Morning Herald, 23 January 1875; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. 102 Years of Age. Western Pioneer’s Death. Treed by Dingoes. Glen Innes Examiner, 23 February 1928; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, J. A Wild Colonial Boy: Thrilling Incidents of Early Days. The Adventures of John McGuire. Truth, 23 April 1911; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- H.J.C. Wild Dog Adventures. Evening Journal, 12 February 1881; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. A Terrible Tramp. The Albury Banner and Wodonga Express, 16 August 1889; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Tree’d by Dingoes. The Bulletin, 12 January 1884; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Sorenson, E.S. The Tale of the Dingo. Sydney Mail, 1 July; 15, 1914; pp. 15, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Story of a Dingo. The School Magazine of Literature for our Boys and Girls, 5(3), 1 April 1920; pp. 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Kernovake, R. An Adventure with Dingoes. Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser, 27 November 1926; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Brave Granny. Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser, 5 November 1932; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Some of My Early Adventures. Australian Town and Country Journal, 3 December 1870; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington, C. Original Poetry: The Schooley’s Adventure. The Tumut Advocate and Farmers and Settlers’ Adviser, 20 November 1906; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Winton, J.M. The Lost Child. Transcontinental, 6 July 1923; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Charnley, W. The Dingo. Walkabout, 26 June 1946; pp. 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Incidents of the Month. Geelong Advertiser, 25 September 1865; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. With Burke and Wills. Survivors’ Memories. The Telegraph, 3 September 1990; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. News from the Interior. The Sydney Morning Herald, 15 September 1842; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Upper Castlereagh River. The Sydney Morning Herald, 17 January 1859; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Our District Council. Northern Territory Times and Gazette, 8 June 1878; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Obituary. The Late Alexander Mckenzie. The Queanbeyan Observer, 20 January 1899; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Paterson, A.B. The Old Bush Songs: Composed and Sung in the Bushranging, Digging, and Overlanding Days; Angus and Robertson: Sydney, Australia, 1905. [Google Scholar]

- Karskens, G. The Colony: A History of Early Sydney; Allen & Unwin: Crowns Nest, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rus, R. Adventure in the Wollombi Mountains. The Weekly Register of Politics, Facts and General Literature, 9 November 1844; p. 233. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, E.H. The Kennel. The Sydney Morning Herald, 8 December 1900; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Colonial News. Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser, 26 September 1876; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Storey, W.K. Big Cats and imperialism: Lion and tiger hunting in Kenya and northern India, 1898–1930. J. World Hist. 1991, 2, 135–173. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, M. The Dingo. Sydney Mail, 23 February 1927; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. No title. The Bulletin, 54, 4 January 1933; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Possum, J. No title. The Bulletin, 49, 25 July 1928; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Drover. The Dingo: Its Fear of the Human Being. Sydney Mail, 8 February 1933; p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Me Bit ‘er Skirt. The Capricornian, 16 August 1928; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Man-Killers Rare in Australian Bush. Sunday Mail, 30 October 1938; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Domino. Dingoes and Their Destruction. Great Southern Leader, 13 April 1928; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Fear of Dingoes. Advising Migrants. Humour and Pathos. The Daily Mail, 22 July 1924; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. No Fear of Dingoes. The Queenslander, 23 January 1936; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Yasmar. Random Notes and Observations. Dingoes and Dogs. The Wingham Chronicle and Manning River Observer, 23 January 1934; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- A Northern Woman. Dingoes. The World’s News, 18 September 1926; p. 8.

- Gouger. No title. The Bulletin, 49, 20 June 1928; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Idriess, I.L. Back O’ Cairns: The Story of Gold Prospecting in the Far North; Angus & Robertson Publishers: London, UK, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Meston, R. On the Management and Diseases of Australian Sheep. No. 22. Wild Dogs. The People’s Advocate and New South Wales Vindicator, 12 June 1852; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Ban on Alsatians. Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser, 31 December 1932; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Alsatians Banned. Potential Danger. Crossing with Dingo. Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser, 17 August 1928; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. “Alsatian” Dingo? Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser, 30 July 1934; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Legislative Assembly Land Estimates. Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser, 9 November 1933; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Iford. The Menace. The Bulletin, 54, 7 June 1933; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Threadingham, T. Wild Dog Trapper Becomes Prey in Patrick Estate Attack. The Gatton, Lockyer and Brisbane Valley Star, 13 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Dangerous Dingoes Will Not Attack Man. The Inverell Times, 8 January 1941; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, J.G. Dingo Habits. Maryborough Chronicle, 16 September 1948; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, J.C. The Dingo. Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser, 3 August 1946; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Missing Man May be Dingo’s Victim. Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, 18 April 1946; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Around the Camp Fire. Townsville Daily Bulletin, 4 November 1947; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- McNeill, A.T.; Luke, K.-P.L.; Goullet, M.S.; Gentle, M.N.; Allen, B.L. Dingoes at the doorstep: Home range sizes and activity patterns of dingoes and other wild dogs around urban areas of north-eastern Australia. Animals 2016, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M. Peri-urban wild dog GPS collar project: Case study. In Proceedings of the 5th Queensland Pest Animal Symposium, Townsville, Australia, 7–10 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Harriott, L.; Gentle, M.; Traub, R.; Soares-Magalhaes, R.; Cobbold, R. Echinococcus granulosus and other zoonotic pathogens of periurban wild dogs in south-east Queensland. In Proceedings of the 5th Queensland Pest Animal Symposium, Townsville, Australia, 7–10 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, B.L.; Allen, L.R.; Amos, M.; Carmelito, E.; Gentle, M.N.; Goullet, M.S.; Leung, L.K.-P.; McNeill, A.T.; Speed, J. Peri-urban wild dogs: Diet and movements in north-eastern Australia. In Proceedings of the 5th Queensland Pest Animal Symposium, Townsville, Australia, 7–10 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, B.L.; Carmelito, E.; Amos, M.; Goullet, M.S.; Allen, L.R.; Speed, J.; Gentle, M.; Leung, L.K.P. Diet of dingoes and other wild dogs in peri-urban areas of north-eastern Australia. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, K.M.; Nesbitt, B.J.; Laffan, S.W.; Letnic, M.; Crowther, M.S. Geographic hot spots of dingo genetic ancestry in southeastern Australia despite hybridisation with domestic dogs. Conserv. Genet. 2019, 21, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentle, M.; Oakey, J.; Speed, J.; Allen, B.; Allen, L. Dingoes, domestic dogs, or hybrids? Genetics of peri-urban wild dogs in NE Australia. In Proceedings of the 5th Queensland Pest Animal Symposium, Townsville, Australia, 7–10 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gentle, M.; Allen, B.L.; Speed, J. Peri-Urban Wild Dogs in North-Eastern Australia: Ecology, Impacts and Management; PestSmart Toolkit Publication, Centre for Invasive Species Solutions: Canberra, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, J. Packs of Wild Dogs Venturing in to Queensland Urban Areas. The Courier Mail, 15 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, F. Brazen Attack: What Will This Killer Take Next? The Gympie Times, 25 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley, C. Safety of Kids and Pets in Doubt as Dingo Attacks Increase. Daily Mercury, 18 January 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alp, C. Beloved Family Pets ‘Torn to Pieces’. Whitsunday Times, 10 January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Shepperson, R. Wild Dog Pack Terrorise Sarina Residents. Daily Mercury, 22 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Elder, K. Loved Pet Killed by Wild Dog Attack on Castle Hill. Townsville Bulletin, 4 January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli, P. Kewarra Beach Family Loses Pup in Wild Dog Attack. The Cairns Post, 4 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Glenday, J. MP Warns of Dingo Dangers in Darwin Suburbs. ABC News, 28 February 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Weston, P. Gold Coast Hinterland Farmers Arm Themselves against Wild Dogs, Sparking Concern the Measures Are Cruel. Gold Coast Bulletin, 7 February 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Arylko. Dog victim: “I Was Screaming—I Thought I Was Going to Die”. Tweed Daily News, 23 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Crockford, T. Young Boy ‘Mauled by Red-Coloured Dog’ on North Queensland Beach. Brisbane Times, 16 January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. A Trip to Botany. The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 10 February 1805; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Sydney. The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 19 August 1815; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Sydney. The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 2 September 1815; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. A Child Lost. Sydney Free Press, 11 September 1841; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Hunter River District News, [From Our Correspondents] Upper Hunter. The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, 11 February 1843; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Melbourne. Geelong Advertiser, 5 December 1844; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, J. Canberra: History of and Legends Relating to the Federal Capital Territory of the Commonwealth of Australia; A.M. Fallick & Sons: Queanbeyan, Australia, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Hunter River District News. The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, 13 April 1850; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Bathurst. Quarter Sessions. The Sydney Morning Herald, 1 February 1850; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Domestic Intelligence. The Argus, 30 October 1851; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Country News. Bathurst Free Press, 4 January 1851; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Local Notes and Events. Queanbeyan Age and General Advertiser, 1 September 1864; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Miscellaneous Information. New South Wales Police Gazette and Weekly Record of Crime, 16 January 1867; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Albany. The Inquirer and Commercial News, 7 September 1870; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Colonial Reminiscences. Two Days at Pammamera. Australian Town and Country Journal, 24 February 1872; pp. 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. A Man Attacked by Native Dogs. Ovens and Murray Advertiser, 13 March 1875; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Local and General. Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser, 7 May 1876; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. No title. The Brisbane Courier, 1 May 1879; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. The Affirmation Bill. South Australian Register, 4 May 1883; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Tragedy of a Lost Child. Chronicle, 24 August 1933; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Local News. Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser, 2 July 1884; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Fifty Years Ago. Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser, 20 January 1934; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Child Lost in the Scrub. South Australian Weekly Chronicle, 10 September 1887; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Carson, W.E. Do Dingoes Eat Men? Chronicle, 24 March 1932; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. News of the Day. The Inquirer and Commercial News, 23 May 1888; p. 5. [Google Scholar]