The Effect of Demonstrator Social Rank on the Attentiveness and Motivation of Pigs to Positively Interact with Their Human Caretakers

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Housing

2.2. Procedures

2.2.1. Determination of Social Dominance Order

2.2.2. Treatments

Gentle Handling Procedure

2.2.3. Behavioral Tests and Measurements

Behavioral Observations

Behavior of the Observer Pigs during and after the Gentle Handling Sessions

Behavior of the Observer Pigs toward the Stockperson in the Home-Pen Test

2.3. Statistics

2.3.1. During and after Gentle Handling Sessions

2.3.2. Home-Pen Test

3. Results

3.1. Behavioral Reaction of Observer Pigs during and after the Gentle Handling Sessions

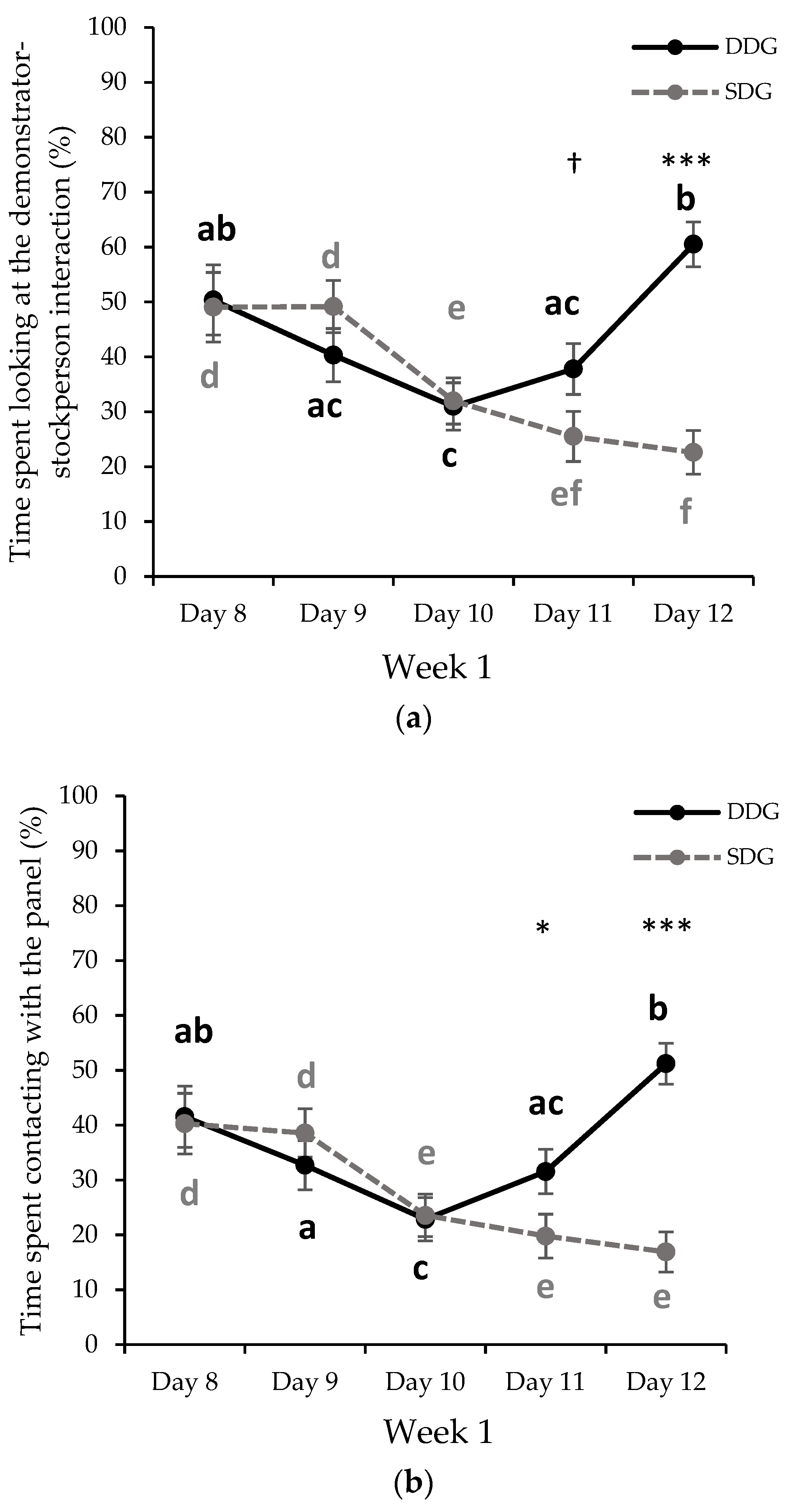

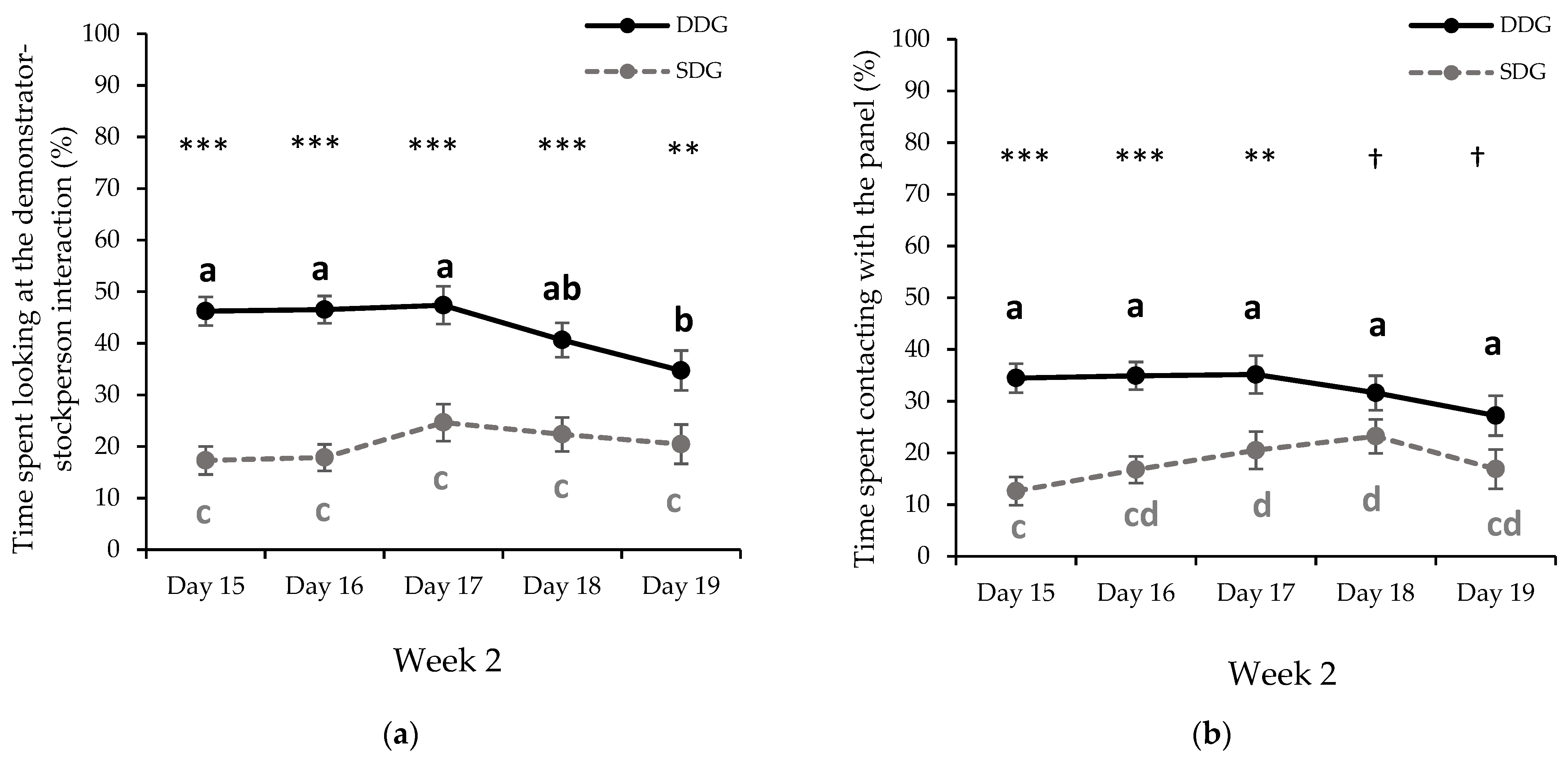

3.1.1. First Week of Gentle Handling Sessions

3.1.2. Second Week of Gentle Handling Sessions

3.2. Behavior toward the Stockperson in the Home-Pen Test

4. Discussion

4.1. Behavioral Reaction of Observer Pigs during and after the Gentle Handling Sessions

4.2. Behavior of the Observer Pigs toward the Stockperson in the Home-Pen Test

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Welfare Quality®. Welfare Quality® Assessment Protocol for Pigs (Sows and Piglets, Growing and Finished Pigs); Welfare Quality® Consortium: Lelystad, The Netherlands, 2009; Available online: http://www.welfarequalitynetwork.net/media/1018/pig_protocol.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2021).

- Mellor, D.J.; Beausoleil, N.J.; Littlewood, K.E.; McLean, A.N.; McGreevy, P.D.; Jones, B.; Wilkins, C. The 2020 Five Domains Model: Including Human-Animal Interactions in Assessments of Animal Welfare. Animals 2020, 10, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkifli, I. Review of human-animal interactions and their impact on animal productivity and welfare. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2013, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waiblinger, S.; Boivin, X.; Pedersen, V.; Tosi, M.-V.; Janczak, A.M.; Visser, E.K.; Jones, R.B. Assessing the human-animal relationship in farmed species: A critical review. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2006, 101, 185–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tallet, C.; Sy, K.; Prunier, A.; Nowak, R.; Boissy, A.; Boivin, X. Behavioural and physiological reactions of piglets to gentle tactile interactions vary according to their previous experience with humans. Livest. Sci. 2014, 167, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, D.; González, C.; Byrd, C.J.; Palomo, R.; Huenul, E.; Figueroa, J. Do Domestic Pigs Acquire a Positive Perception of Humans through Observational Social Learning? Animals 2021, 11, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brajon, S.; Laforest, J.P.; Bergeron, R.; Tallet, C.; Hötzel, M.J.; Devillers, N. Persistency of the piglet’s reactivity to the handler following a previous positive or negative experience. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2015, 162, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensoussan, S.; Tigeot, R.; Meunier-Salaün, M.C.; Tallet, C. Broadcasting human voice to piglets (Sus scrofa domestica) modifies their behavioural reaction to human presence in the home pen and in arena tests. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2020, 225, 104965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tallet, C.; Brajon, S.; Devillers, N.; Lensink, J. Pig–human interactions: Creating a positive perception of humans to ensure pig welfare. In Advances in Pig Welfare, 1st ed.; Špinka, M., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Duxford, UK, 2018; pp. 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima Rocha, A.D.; Menescal-de-Oliveira, L.; da Silva, L.F.S. Effects of human contact and intra-specific social learning on tonic immobility in guinea pigs, Cavia porcellus. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 191, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, S.; Hemery, D.; Richard-Yris, M.A.; Hausberger, M. Human-mare relationships and behaviour of foals toward humans. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2005, 93, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munksgaard, L.; De Passillé, A.M.; Rushen, J.; Herskin, M.S.; Kristensen, A.M. Dairy cows’ fear of people: Social learning, milk yield and behaviour at milking. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2001, 73, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyes, C.M. Social learning in animals: Categories and mechanisms. Biol. Rev. 1994, 69, 207–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugatkin, L.A.; Godin, J.G.J. Female mate copying in the guppy (Poecilia reticulata): Age-dependent effects. Behav. Ecol. 1993, 4, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, A.E.; Whiten, A.; van Schaik, C.; Krützen, M.; Eichenberger, F.; Schnider, A.; van de Waal, E. Payoff-and sex-biased social learning interact in a wild primate population. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, 2800–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henrich, J.; Gil-White, F. The evolution of prestige: Freely conferred deference as a mechanism for enhancing the benefits of cultural transmission. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2001, 22, 165–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, V.; Proctor, D.; Bonnie, K.E.; Whiten, A.; de Waal, F.B. Prestige affects cultural learning in chimpanzees. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kendal, R.; Hopper, L.M.; Whiten, A.; Brosnan, S.F.; Lambeth, S.P.; Schapiro, S.J.; Hoppitt, W. Chimpanzees copy dominant and knowledgeable individuals: Implications for cultural diversity. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2015, 36, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nicol, C.J.; Pope, S.J. Social learning in small flocks of laying hens. Anim. Behav. 1994, 47, 1289–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nicol, C.J.; Pope, S.J. The effects of demonstrator social status and prior foraging success on social learning in laying hens. Anim. Behav. 1999, 57, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Krueger, K.; Heinze, J. Horse sense: Social status of horses (Equus caballus) affects their likelihood of copying other horses‘ behavior. Anim. Cogn. 2008, 11, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongrácz, P.; Vida, V.; Bánhegyi, P.; Miklósi, Á. How does dominance rank status affect individual and social learning performance in the dog (Canis familiaris). Anim. Cogn. 2008, 11, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canteloup, C.; Hoppitt, W.; van de Waal, E. Wild primates copy higher-ranked individuals in a social transmission experiment. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krueger, K.; Farmer, K.; Heinze, J. The effects of age, rank and neophobia on social learning in horses. Anim. Cogn. 2014, 17, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dindo, M.; Leimgruber, K.L.; Ahmed, R.; Whiten, A.; de Waal, F.B. Observer choices during experimental foraging tasks in brown capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella). Am. J. Primatol. 2011, 73, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botting, J.; Whiten, A.; Grampp, M.; van de Waal, E. Field experiments with wild primates reveal no consistent dominance-based bias in social learning. Anim. Behav. 2018, 136, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boogert, N.J.; Reader, S.M.; Laland, K.N. The relation between social rank, neophobia and individual learning in starlings. Anim. Behav. 2006, 72, 1229–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, C.A.; Whiten, A. Scrounging facilitates social learning in common marmosets, Callithrix jacchus. Anim. Behav. 2003, 65, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zajonc, R.B. Social facilitation. Science 1965, 149, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmeau, R.; Gallo, A. Social constraints determine what is learned in the chimpanzee. Behav. Process. 1993, 28, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drea, C.M.; Wallen, K. Low-status monkeys “play dumb” when learning in mixed social groups. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 12965–12969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- National Research Council. Nutrient Requirements of Swine, 11th ed.; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; 400p. [Google Scholar]

- Stukenborg, A.; Traulsen, I.; Puppe, B.; Presuhn, U.; Krieter, J. Agonistic behaviour after mixing in pigs under commercial farm conditions. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2011, 129, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friard, O.; Gamba, M. BORIS: A free, versatile open-source event-logging software for video/audio coding and live observations. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 1325–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemsworth, P.H.; Barnett, J.L. The effects of aversively handling pigs, either individually or in groups, on their behaviour, growth and corticosteroids. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1991, 30, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, D.C. Multiple comparisons among treatment means. In Statistical Methods for Psychology, 8th ed.; Wadsworth Cengage Learning: Belmont, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 369–410. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, P.; Bateson, P. Statistical analysis. In Measuring Behaviour: An Introductory Guide, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994; pp. 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn-Eimermacher, A.; Lasarzik, I.; Raber, J. Statistical analysis of latency outcomes in behavioral experiments. Behav. Brain Res. 2011, 221, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beasley, T.M.; Schumacker, R.E. Multiple regression approach to analyzing contingency tables: Post hoc and planned comparison procedures. J. Exp. Educ. 1995, 64, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coussi-Korbel, S.; Fragaszy, D.M. On the relation between social dynamics and social learning. Anim. Behav. 1995, 50, 1441–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grampp, M.; Sueur, C.; van de Waal, E.; Botting, J. Social attention biases in juvenile wild vervet monkeys: Implications for socialisation and social learning processes. Primates 2019, 60, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalmaso, M.; Pavan, G.; Castelli, L.; Galfano, G. Social status gates social attention in humans. Biol. Lett. 2012, 8450–8452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Raoult, C.M.; Gygax, L. Mood induction alters attention toward negative-positive stimulus pairs in sheep. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandalaywala, T.M.; Parker, K.J.; Maestripieri, D. Early experience affects the strength of vigilance for threat in rhesus monkey infants. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 25, 1893–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goumon, S.; Špinka, M. Emotional contagion of distress in young pigs is potentiated by previous exposure to the same stressor. Anim. Cogn. 2016, 19, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubo, M.; Gamer, M. Social content and emotional valence modulate gaze fixations in dynamic scenes. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanida, H.; Nagano, Y. The ability of miniature pigs to discriminate between a stranger and their familiar handler. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1998, 56, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Bratslavsky, E.; Finkenauer, C.; Vohs, K.D. Bad is stronger than good. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2001, 5, 323–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.K.; Cacioppo, J.T.; Larsen, J.T.; Chartrand, T.L. May I have your attention, please: Electrocortical responses to positive and negative stimuli. Neuropsychologia 2003, 41, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.X.; Luo, Y.J. Can negative stimuli always have the processing superiority? Acta Psychol. Sin. 2009, 41, 822–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Range, F.; Huber, L. Attention in common marmosets: Implications for social-learning experiments. Anim. Behav. 2007, 73, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Range, F.; Horn, L.; Bugnyar, T.; Gajdon, G.K.; Huber, L. Social attention in keas, dogs, and human children. Anim. Cogn. 2009, 12, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Figueroa, J.; Solà-Oriol, D.; Manteca, X.; Pérez, J.F. Social learning of feeding behaviour in pigs: Effects of neophobia and familiarity with the demonstrator conspecific. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2013, 148, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemsworth, P.H.; Gonyou, H.W.; Dziuk, P.J. Human communication with pigs: The behavioural response of pigs to specific human signals. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1986, 15, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, A.; Tanida, H.; Tanaka, T.; Yoshimoto, T. The influence of human posture and movement on the approach and escape behaviour of weanling pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1996, 49, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rault, J.L.; Waiblinger, S.; Boivin, X.; Hemsworth, P. The power of a positive human-animal relationship for animal welfare. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 590867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindo, M.; Whiten, A.; de Waal, F.B. Social facilitation of exploratory foraging behavior in capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella). Am. J. Primatol. 2009, 71, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welp, T.; Rushen, J.; Kramer, D.L.; Festa-Bianchet, M.; De Passille, A.M.B. Vigilance as a measure of fear in dairy cattle. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2004, 87, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, D.; Paranhos da Costa, M.J.R.; Zupan, M.; Rehn, T.; Keeling, L.J. Early human handling in non-weaned piglets: Effects on behaviour and body weight. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2015, 164, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Borell, E.; Langbein, J.; Després, G.; Hansen, S.; Leterrier, C.; Marchant-Forde, J.; Marchant-Forde, R.; Minero, M.; Mohr, E.; Prunier, A.; et al. Heart rate variability as a measure of autonomic regulation of cardiac activity for assessing stress and welfare in farm animals—A review. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 92, 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemsworth, P.H.; Barnett, J.L.; Hansen, C. The influence of handling by humans on the behavior, growth, and corticosteroids in the juvenile female pig. Horm. Behav. 1981, 15, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdorf, E.V.; Bonnie, K.E.; Grim, M.; Krupnick, A.; Prestipino, M.; Whyte, J. Seeding an arbitrary convention in capuchin monkeys: The effect of social context. Behaviour 2016, 153, 633–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, S.K.; Reamer, L.A.; Mareno, M.C.; Vale, G.; Harrison, R.A.; Lambeth, S.P.; Schapiro, S.J.; Whiten, A. Socially transmitted diffusion of a novel behavior from subordinate chimpanzees. Am. J. Primatol. 2017, 79, e22642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicol, C.J. Development, direction, and damage limitation: Social learning in domestic fowl. Anim. Learn. Behav. 2004, 32, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Robichaud, D.; Lefebvre, L.; Robidoux, L. Dominance affects resource partitioning in pigeons but pair bonds do not. Can. J. Zool. 1996, 74, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, B.A.; Meese, G.B. Social behaviour in pigs studied by means of operant conditioning. Anim. Behav. 1979, 27, 947–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolba, A.; Wood-Gush, D.G.M. The behaviour of pigs in a semi-natural environment. Anim. Sci. 1989, 48, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langbein, J.; Puppe, B. Analysing dominance relationships by sociometric methods—A plea for a more standardised and precise approach in farm animals. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2004, 87, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, S.; Mendl, M.; Laughlin, K.; Byrne, R.W. Cognition studies with pigs: Livestock cognition and its implication for production. J. Anim. Sci. 2002, 80, E10–E17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imfeld-Mueller, S.; Van Wezemael, L.; Stauffacher, M.; Gygax, L.; Hillmann, E. Do pigs distinguish between situations of different emotional valences during anticipation? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2011, 131, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, L.R.; Nielsen, B.L.; Larsen, O.N. Implications of food patch distribution on social foraging in domestic pigs (Sus scrofa). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2010, 122, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Day of the Experiment | Pigs Age (Days) | Event/Test | Place | Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 21 | Weaning | Commercial farm | - |

| 1–7 | 21–27 | Acclimation to nursery pens | Home pen | - |

| 1–2 | 21–22 | Agonistic behavior video collection | Home pen | Behavioral |

| 3–5 | 23–25 | Agonistic behavior video analysis | - | Behavioral |

| 6 | 26 | Dominance Index estimation | - | Dominance index |

| 8–40 | 28–60 | Gentle handling (GH) sessions | Home pen | Behavioral |

| 8–12 | 28–32 | Behavioral video collection during and after GH sessions | Home pen | Behavioral |

| 15–19 | 35–39 | Behavioral video collection during and after GH sessions | Home pen | Behavioral |

| 41–42 | 61–62 | Home-pen test | Home pen | Behavioral |

| Behavioral Observations during GH Sessions | Description |

|---|---|

| Looking at the demonstrator-stockperson interaction | Time (%) that the observer pig stood still within 20 cm of the acrylic panel with its head oriented toward the demonstrator–stockperson dyad while the demonstrator was gently handled by the stockperson. The percentage of time was calculated as a function of the entire 10 min during the GH session. |

| Frequency of looking at the demonstrator–stockperson interaction | Number of times the observer pig stood still within 20 cm of the acrylic panel with its head oriented toward the demonstrator–stockperson dyad while the demonstrator was gently handled by the stockperson. |

| Time of contact with the panel | Time (%) the observer pig spent with their snout physically contacting the acrylic panel and/or the holes of the panel (touching or sniffing) with their head oriented toward the demonstrator–stockperson dyad. The percentage of time was calculated as a function of the entire 10 min during the GH session. |

| Frequency of contact with the panel | Number of times the observer pig physically contacted the acrylic panel with their snout, while their head was oriented toward the demonstrator-stockperson dyad. |

| Frequency of climbing on the panel | Number of times the observer pig’s two front legs made contact with the acrylic panel in a single motion while standing on its two hind legs. |

| Behavioral Observations after GH Sessions | |

| Time of snout–snout contact | Time (%) the observer pig spent touching the end of the demonstrator’s snout with the end of its own snout. The percentage of time was calculated as a function of the entire 3 min after the GH session. |

| Frequency of snout–snout contact | Number of times the observer pig touched the demonstrator pig’s snout with its own snout. |

| Behavioral Observation | Description | Phase |

|---|---|---|

| Latency to first physical contact | Time (s) taken for the pig to make physical contact with any part of the stockperson’s body. | 1,2 |

| Time of physical contact | Time (%) pig stayed in physical contact with any part of the stockperson’s body, either touching or sniffing. The percentage of time was calculated as a function of the minutes elapsed for each phase. | 1,2 |

| Looking at the stockperson | Time (%) pig stood still looking at the stockperson, with its body and head oriented toward the stockperson without physically interacting with her. The percentage of time was calculated as a function of the minutes elapsed for each phase. | 1,2 |

| Frequency of contact | Number of times the pig physically contacted any part of body of the stockperson. | 1,2 |

| Frequency of climbing on the stockperson | Number of times the pig was observed climbing on the stockperson, with at least the front legs on the thighs. | 2,3 |

| Animals climbing on the stockperson | Number of animals that were observed climbing on the stockperson, with at least the front legs on the thighs. | 2,3 |

| Accepted strokes | Strokes (%) accepted by each pig based on the total attempts made by the stockperson. The percentage of strokes was calculated as a function of the total attempts made by the stockperson during Phase 3. | 3 |

| Attempts required until accepting the first stroke | Number of attempts made by the stockperson until the pig accepted the first stroke. | 3 |

| Behavior | Week | Treatments | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDG | SDG | |||

| (n = 20) | (n = 20) | |||

| During GH sessions | ||||

| Looking at the DSI (%) | Week 1 | 43.98 ± 3.26 p | 35.65 ± 3.14 q | 0.077 1 |

| Week 2 | 43.09 ± 2.22 a | 20.52 ± 2.14 b | <0.001 1 | |

| Frequency of looking at the DSI | Week 1 | 9.35 ± 0.54 | 9.05 ± 0.52 | 0.678 2 |

| Week 2 | 8.44 ± 0.57 a | 6.48 ± 0.55 b | 0.019 2 | |

| Time of contact with the panel (%) | Week 1 | 35.97 ± 3.03 p | 27.81 ± 2.92 q | 0.071 1 |

| Week 2 | 32.67 ± 2.24 a | 17.99 ± 2.16 b | <0.001 1 | |

| Frequency of contact with the panel | Week 1 | 12.61 ± 0.84 | 11.78 ± 0.81 | 0.484 2 |

| Week 2 | 9.97 ± 0.74 a | 7.70 ± 0.71 b | 0.035 2 | |

| Frequency of climbing on the panel | Week 1 | 0.45 ± 0.14 | 0.32 ± 0.14 | 0.473 3 |

| Week 2 | 0.44 ± 0.10 | 0.44 ± 0.10 | 0.961 3 | |

| After GH sessions | ||||

| Time of snout–snout contact (%) | Week 1 | 1.30 ± 0.24 | 0.84 ± 0.23 | 0.170 1 |

| Week 2 | 0.99 ± 0.27 | 0.88 ± 0.26 | 0.759 1 | |

| Frequency of snout–snout contact | Week 1 | 1.02 ± 0.05 | 0.95 ± 0.05 | 0.319 3 |

| Week 2 | 0.47 ± 0.10 | 0.49 ± 0.10 | 0.874 3 |

| Behavior | Treatments | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG | DDG | SDG | ||

| (n = 25) | (n = 20) | (n = 20) | ||

| Phase 1 | ||||

| Latency to first contact (s) | 10.41 ± 2.34 | 16.67 ± 5.04 | 15.88 ± 5.19 | 0.640 2 |

| Time of contact (%) | 69.70 ± 10.21 | 70.95 ± 10.59 | 67 ± 10.60 | 0.940 1a |

| Frequency of contact | 2.40 ± 0.25 a | 1.35 ± 0.27 b | 1.30 ± 0.27 b | 0.020 1 |

| Time looking at the stockperson (%) | 10.67 (3.83–22.49) a | 6.15 (0–16.94) a | 1.04 (0–9.28) b | 0.022 3 |

| Phase 2 | ||||

| Latency to first contact (s) | 3.80 ± 0.82 a | 16.29 ± 8.03 a | 1.00 ± 0 b | <0.001 2 |

| Time of contact (%) | 86.67 (72.86–88.44) a | 84.88 (81.54–88.27) a | 100 (96.53–100) b | 0.007 3 |

| Frequency of contact | 3.44 ± 0.52 | 2.20 ± 0.54 | 2.70 ± 0.54 | 0.294 1 |

| Time looking at the stockperson (%) | 10.04 (0–16.40) a | 10.75 (0–15.12) a | 0 (0–0) b | 0.001 3 |

| Climbing on the stockperson (frequency) | 1.44 ± 0.52 | 0.80 ± 0.53 | 1.25 ± 0.53 | 0.691 1 |

| Phase 3 | ||||

| Accepted strokes (%) | 76.47 (27.14–100) a | 82.35 (62.50–93.33) a | 100 (93.68–100) b | 0.003 3 |

| Attempts until accepting the first stroke | 2.00 (1.00–4.50) a | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) a,b | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) b | 0.002 3 |

| Climbing on the stockperson (frequency) | 1.88 ± 0.48 | 1.57 ± 0.53 | 1.35 ± 0.52 | 0.761 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luna, D.; González, C.; Byrd, C.J.; Palomo, R.; Huenul, E.; Figueroa, J. The Effect of Demonstrator Social Rank on the Attentiveness and Motivation of Pigs to Positively Interact with Their Human Caretakers. Animals 2021, 11, 2140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11072140

Luna D, González C, Byrd CJ, Palomo R, Huenul E, Figueroa J. The Effect of Demonstrator Social Rank on the Attentiveness and Motivation of Pigs to Positively Interact with Their Human Caretakers. Animals. 2021; 11(7):2140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11072140

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuna, Daniela, Catalina González, Christopher J. Byrd, Rocío Palomo, Elizabeth Huenul, and Jaime Figueroa. 2021. "The Effect of Demonstrator Social Rank on the Attentiveness and Motivation of Pigs to Positively Interact with Their Human Caretakers" Animals 11, no. 7: 2140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11072140

APA StyleLuna, D., González, C., Byrd, C. J., Palomo, R., Huenul, E., & Figueroa, J. (2021). The Effect of Demonstrator Social Rank on the Attentiveness and Motivation of Pigs to Positively Interact with Their Human Caretakers. Animals, 11(7), 2140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11072140