Prevalence of Fascioliasis and Associated Economic Losses in Cattle Slaughtered at Lira Municipality Abattoir in Northern Uganda

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

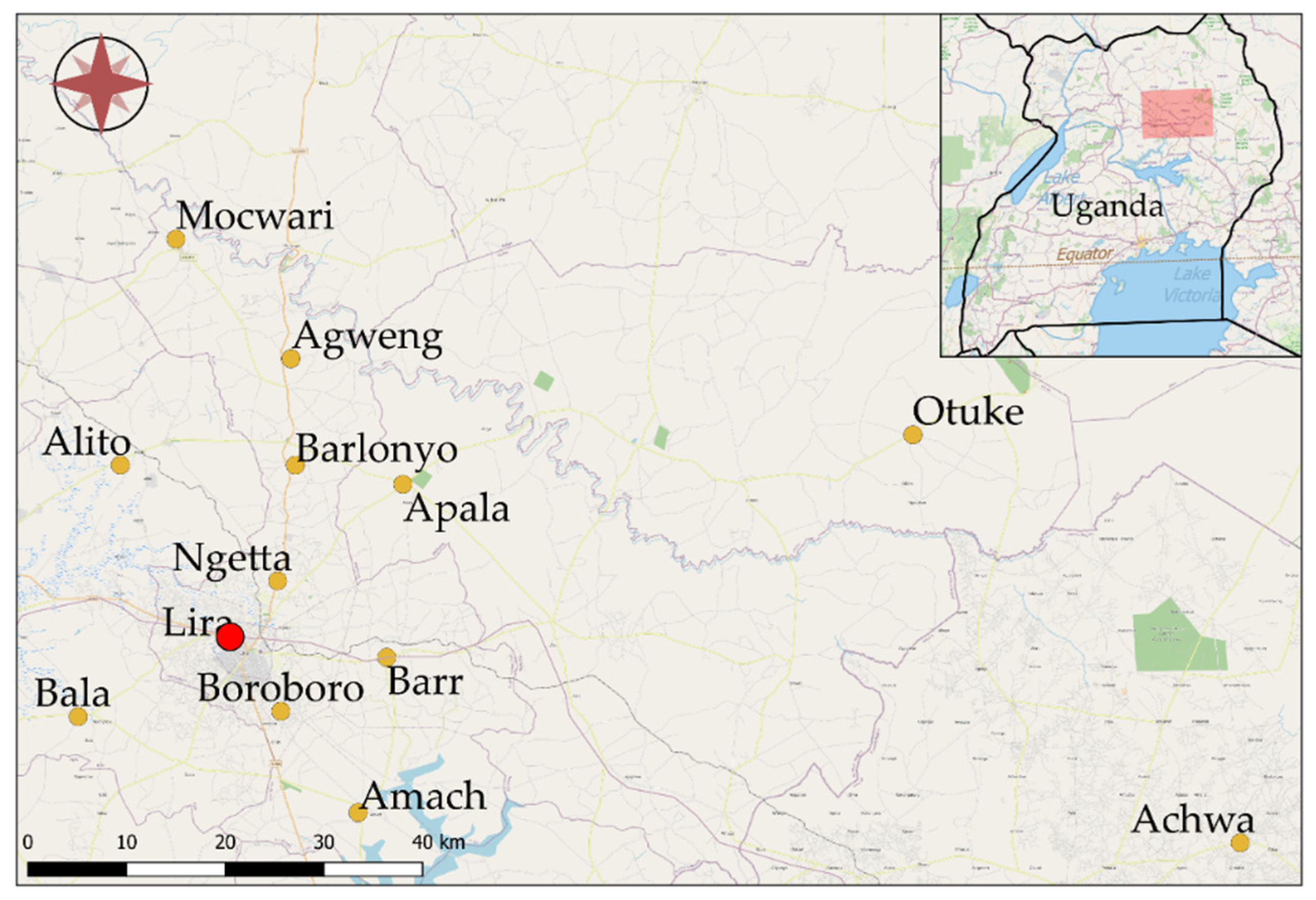

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Sample Collection and Gross Examination

2.3. Liver Condemnation and Associated Financial Loss

2.4. Sample Size Calculation

2.5. Data Management and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Cattle Assessed in This Study

3.2. Prevalence of Fascioliasis in Slaughtered Cattle

3.3. Risk Factors for Fasciola Infestation

3.4. Financial Losses Associated with Liver Condemnation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rana, M.A.A.; Roohi, N.; Khan, M.A. Fascioliasis in cattle—A review. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2014, 24, 668–675. [Google Scholar]

- Mas-Coma, S.; Bargues, M.D.; Valero, M.A. Fascioliasis and other plant-borne trematode zoonoses. Int. J. Parasitol. 2005, 35, 1255–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaji, A.A.; Ibrahim, K.; Salihu, M.D.; Saulawa, M.A.; Mohammed, A.A.; Musawa, A.I. Prevalence of Fascioliasis in Cattle Slaughtered in Sokoto Metropolitan Abattoir, Sokoto, Nigeria. Adv. Epidemiol. 2014, 2014, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Tahawy, A.S.; Bazh, E.K.; Khalafalla, R.E. Epidemiology of bovine fascioliasis in the Nile Delta region of Egypt: Its prevalence, evaluation of risk factors, and its economic significance. Vet. World 2017, 10, 1241–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, A.; Frankena, K.; Bødker, R.; Toft, N.; Thamsborg, S.M.; Enemark, H.L.; Halasa, T. Prevalence, risk factors and spatial analysis of liver fluke infections in Danish cattle herds. Parasites Vectors 2015, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaja, I.F.; Mushonga, B.; Green, E.; Muchenje, V. Seasonal prevalence, body condition score and risk factors of bovine fasciolosis in South Africa. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2017, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getahun, A.; Aynalem, Y.; Haile, A. Prevalence of Bovine fasciolosis infectionin Hossana municipal abattoir, Southern Ethiopia. J. Nat. Sci. Res. 2017. Available online: www.iiste.org (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Onyeabor, A.; Wosu, M. Prevalence of Bovine Fasciolosis Observed in Three Major Abattoirs in Abia State Nigeria. J. Vet. Adv. 2014, 4, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardo, M.; Aliyara, Y.; Lawal, H. Prevalence of Bovine Fasciolosis in major Abattiors of Adamawa State, Nigeria. Bayero J. Pure Appl. Sci. 2013, 6, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio Silva, M.L.; Correia Da Costa, J.M.; Viana Da Costa, A.M.; Pires, M.A.; Lopes, S.A.; Castro, A.M.; Monjour, L. Antigenic components of excretory-secretory products of adult Fasciola hepatica recognized in human infections. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1996, 54, 146–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odigie, B.E.; Odigie, J.O. Fascioliasis in Cattle: A Survey of Abattoirs in Egor, Ikpoba- Okha and Oredo Local Government Areas of Edo State, Using Histochemical Techniques. Int. J. Basic Appl. Innov. Res. 2013, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mas-Coma, S.; Bargues, M.D. Human Liver Flukes: A Review. Res. Rev. Parasitol. 1997, 57, 145–218. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban, J.G.; Gonzalez, C.; Curtale, F.; Muñoz-Antoli, C.; Valero, M.A.; Bargues, M.D.; El Sayed, M.; El Wakeel, A.A.E.W.; Abdel-Wahab, Y.; Montresor, A.; et al. Hyperendemic fascioliasis associated with schistosomiasis in villages in the Nile Delta of Egypt. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2003, 69, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujawa, M. Control of Foodborne Trematode Infections. WHO Technical Report Series 849. 157 Seiten, 4 Tabellen. World Health Organization, Geneva 1995. Preis: 26—Sw.fr. Food/Nahrung 1996, 40, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spithill, T.W.; Smooker, P.M.; Copeman, D.B. Fasciola Gigantica: Epidemiology, Control, Immunology, and Molecular Biology; Dalton, F.J.P., Ed.; Commonwealth Agriculture Bureau International Publishing: New York, UK; Wallingford, UK, 1999; pp. 465–525. [Google Scholar]

- Chick, B.F.; Blumer, C.; Veterinary, D.; Mailbag, P. Economic significance of Fasciola hepatica infestation of beef cattle—A definition study based on field trial and grazier questionnaire. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium on Veterinary Epidemiology and Economics, Canberra, Australia, 7–11 May 1979; pp. 377–382. [Google Scholar]

- Food Safety Inspection Service. Using Dentition to Age Cattle; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. Available online: https://www.fsis.usda.gov/OFO/TSC/bse_information.htm (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Wildman, E.E.; Jones, G.M.; Wagner, P.E.; Boman, R.L.; Troutt, H.F.; Lesch, T.N. A Dairy Cow Body Condition Scoring System and Its Relationship to Selected Production Characteristics. J. Dairy Sci. 1982, 65, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herenda, D.; Chambers, P.G.; Ettriqui, A.; Seneviratnap, P.; DaSilvat, T.J.P. Manual on Meat Inspection for Developing Countries; FAO Animal Production and Health Paper 119; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Techniques, 2nd ed.; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, A.; Mugisha, L.; Davies, J.; Lacourse, E.J.; Claridge, J.; Williams, D.J.; Kelly-Hope, L.; Betson, M.; Kabatereine, N.B.; Stothard, J.R. Bovine fasciolosis at increasing altitudes: Parasitological and malacological sampling on the slopes of Mount Elgon, Uganda. Parasites Vectors 2012, 5, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jean-Richard, V.; Crump, L.; Abicho, A.A.; Naré, N.B.; Greter, H.; Hattendorf, J.; Schelling, E.; Zinsstag, J. Prevalence of Fasciola gigantica infection in slaughtered animals in south-eastern Lake Chad area in relation to husbandry practices and seasonal water levels. BMC Vet. Res. 2014, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ssimbwa, G.; Baluka, S.A.; Ocaido, M. Prevalence and financial losses associated with bovine fasciolosis at Lyantonde Town. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2014, 26, 165. Available online: http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd26/9/ssim26165.html (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Joan, N.; Stephen, M.; Bashir, M.; Kiguli, J.; Orikiriza, P.; Bazira, J.; Itabangi, H.; Stanley, I. Prevalence and Economic Impact of Bovine Fasciolosis at Kampala City Abattoir, Central Uganda. Br. Microbiol. Res. J. 2015, 7, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekwunife, C.A.; Eneanya, C.I. Fasciola gigantica in Onitsha and environs. Anim. Res. Int. 2008, 3, 448–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kithuka, J.M.; Maingi, N.; Njeruh1, F.M.; Ombui1, J.N. The Prevalence and Economic Importance of Bovine Fasciolosis in Kenya—An Analysis of Abattoir Data. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 2002, 69, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, S.T.; Nguyen, D.T.; van Nguyen, T.; Huynh, V.V.; Le, D.Q.; Fukuda, Y.; Nakai, Y. Prevalence of Fasciola in cattle and of its intermediate host Lymnaea snails in central Vietnam. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2012, 44, 1847–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyirenda, S.S.; Sakala, M.; Moonde, L.; Kayesa, E.; Fandamu, P.; Banda, F.; Sinkala, Y. Prevalence of bovine fascioliasis and economic impact associated with liver condemnation in abattoirs in Mongu district of Zambia. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abunna, F.; Asfaw, L.; Megersa, B.; Regassa, A. Bovine fasciolosis: Coprological, abattoir survey and its economic impact due to liver condemnation at Soddo municipal abattoir, Southern Ethiopia. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2010, 42, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragaw, K.; Negus, Y.; Denbarga, Y.; Sheferaw, D. Fasciolosis in slaughtered cattle in Addis Ababa abattoir, Ethiopia. Glob. Vet. 2012, 8, 115–118. [Google Scholar]

- Dawa, D.; Abattoir, M.; Mebrahtu, G.; Beka, K. Prevalence and economic significance of fasciolosis in cattle slaughtered at Dire Dawa Municipal Abattoir, Ethiopia. J. Vet. Adv. 2013, 3, 319–324. [Google Scholar]

- Demssie, A.; Birku, F.; Biadglign, A. An Abattoir survey on the prevalence and monetary loss of fasciolosis in cattle in Jimma Town, Ethiopia. Glob. Vet. 2012, 8, 381–385. [Google Scholar]

- Jaja, I.F.; Mushonga, B.; Green, E.; Muchenje, V. A quantitative assessment of causes of bovine liver condemnation and its implication for food security in the Eastern Cape province South Africa. Sustainability 2017, 9, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Andrade, R.; Paz-Silva, A.; Suárez, J.L.; Panadero, R.; Pedreira, J.; López, C. Influence of age and breed on natural bovine fasciolosis in an endemic area (Galicia, NW Spain). Vet. Res. Commun. 2002, 26, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.N.; Sajid, M.S.; Khan, M.K.; Iqbal, Z.; Hussain, A. Gastrointestinal helminthiasis: Prevalence and associated determinants in domestic ruminants of district Toba Tek Singh, Punjab, Pakistan. Parasitol. Res. 2010, 107, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.K.; Sajid, M.S.; Khan, M.N.; Iqbal, Z.; Iqbal, M.U. Bovine fasciolosis: Prevalence, effects of treatment on productivity and cost benefit analysis in five districts of Punjab, Pakistan. Res. Vet. Sci. 2009, 87, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyaji, F.O.; Yaro, C.A.; Peter, M.F.; Abutu, A.E.O. Fasciola hepatica and Associated Parasite, Dicrocoelium dendriticum in Slaughterhouses in Anyigba, Kogi State, Nigeria. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2018, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zeleke, G.; Menkir, S.; Desta, M. Original article Prevalence of ovine fasciolosis and its economic significance in Basona worana district, central Ethiopia. Sci. J. Zool. 2013, 2, 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Simwanza, C.; Mumba, C.; Pandey, G.S.; Samui, K.L. Financial Losses Arising from Condemnation of Liver Due to Financial Losses Arising from Condemnation of Liver Due to Fasciolosis in Cattle from the Western Province of Zambia. Int. J. Livest. Res. 2012, 2, 133–137. [Google Scholar]

- Mehmood, K.; Zhang, H.; Sabir, A.J.; Abbas, R.Z.; Ijaz, M.; Durrani, A.Z.; Saleem, M.H.; Ur Rehman, M.; Iqbal, M.K.; Wang, Y.; et al. A review on epidemiology, global prevalence, and economical losses of fasciolosis in ruminants. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 109, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | n | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Region | ||

| Southern a | 131 | 54.17 |

| Eastern b | 76 | 35.19 |

| Northern c | 9 | 10.65 |

| Breed | ||

| Small East African Zebu | 194 | 89.81 |

| Ankole | 22 | 10.19 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 160 | 25.93 |

| Female | 56 | 74.10 |

| Age of animal at slaughter, years | ||

| 0–3.5 | 74 | 34.26 |

| 4–5 | 125 | 57.87 |

| 6–10 | 17 | 7.87 |

| Body condition score | ||

| 3 | 75 | 34.72 |

| 3.5 | 129 | 59.72 |

| 4 | 12 | 5.56 |

| Gross weight of liver at slaughter (Kg) | ||

| 0–2 | 50 | 23.15 |

| 2.1–4 | 149 | 68.98 |

| 4.1–6 | 17 | 7.87 |

| Fasciola infestation | ||

| Yes | 142 | 65.74 |

| No | 74 | 34.26 |

| Trimmed part of liver (Kg) | ||

| 0–1 | 169 | 78.24 |

| 1.1–2 | 36 | 16.67 |

| 2.1–5 | 11 | 5.10 |

| Category | n | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Region 1 | ||

| Southern | 88 | 64.10 |

| Eastern | 48 | 63.15 |

| Northern | 6 | 82.61 |

| Breed | ||

| Small East African Zebu | 131 | 67.52 |

| Ankole | 11 | 50 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 110 | 68.75 |

| Male | 32 | 57.14 |

| Age of animal at slaughter, years | ||

| 0–3.5 | 32 | 43.24 |

| 4–5 | 98 | 78.40 |

| 6–10 | 12 | 70.58 |

| Body condition score | ||

| 3 | 52 | 69.33 |

| 3.5 | 83 | 64.34 |

| 4 | 7 | 58.33 |

| Gross weight of liver at slaughter, kg | ||

| 0–2 | 28 | 56 |

| 2.1–4 | 100 | 67.11 |

| 4.1–6 | 14 | 82.35 |

| Variable | OR | SE | 95% CI | p-Value 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Region | |||||

| Southern a | Referent | ||||

| Eastern b | 0.92 | 0.31 | 0.47 | 1.78 | 0.800 |

| Northern c | 1.83 | 1.18 | 0.51 | 6.53 | 0.348 |

| Breed | |||||

| Small East African Zebu | Referent | ||||

| Ankole | 0.63 | 0.33 | 0.22 | 1.81 | 0.391 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | Referent | ||||

| Male | 1.55 | 0.55 | 0.76 | 3.14 | 0.224 |

| Age of animal at slaughter, years | |||||

| 0–3.5 | Referent | ||||

| 4–5 | 5.84 | 2.20 | 2.79 | 12.22 | 0.001 |

| 6–10 | 2.77 | 1.78 | 0.78 | 9.76 | 0.113 |

| Body condition score | |||||

| 3 | Referent | ||||

| 3.5 | 0.42 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.88 | 0.023 |

| 4 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 1.10 | 0.064 |

| Gross weight of liver at slaughter, kg | |||||

| 0–2 | Referent | ||||

| 2.1–4 | 1.15 | 0.45 | 0.52 | 2.51 | 0.725 |

| 4.1–6 | 2.96 | 2.71 | 0.50 | 17.80 | 0.236 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Opio, L.G.; Abdelfattah, E.M.; Terry, J.; Odongo, S.; Okello, E. Prevalence of Fascioliasis and Associated Economic Losses in Cattle Slaughtered at Lira Municipality Abattoir in Northern Uganda. Animals 2021, 11, 681. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11030681

Opio LG, Abdelfattah EM, Terry J, Odongo S, Okello E. Prevalence of Fascioliasis and Associated Economic Losses in Cattle Slaughtered at Lira Municipality Abattoir in Northern Uganda. Animals. 2021; 11(3):681. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11030681

Chicago/Turabian StyleOpio, Lawrence George, Essam M. Abdelfattah, Joshua Terry, Steven Odongo, and Emmanuel Okello. 2021. "Prevalence of Fascioliasis and Associated Economic Losses in Cattle Slaughtered at Lira Municipality Abattoir in Northern Uganda" Animals 11, no. 3: 681. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11030681

APA StyleOpio, L. G., Abdelfattah, E. M., Terry, J., Odongo, S., & Okello, E. (2021). Prevalence of Fascioliasis and Associated Economic Losses in Cattle Slaughtered at Lira Municipality Abattoir in Northern Uganda. Animals, 11(3), 681. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11030681