Factors That Optimize Reproductive Efficiency in Dairy Herds with an Emphasis on Timed Artificial Insemination Programs

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

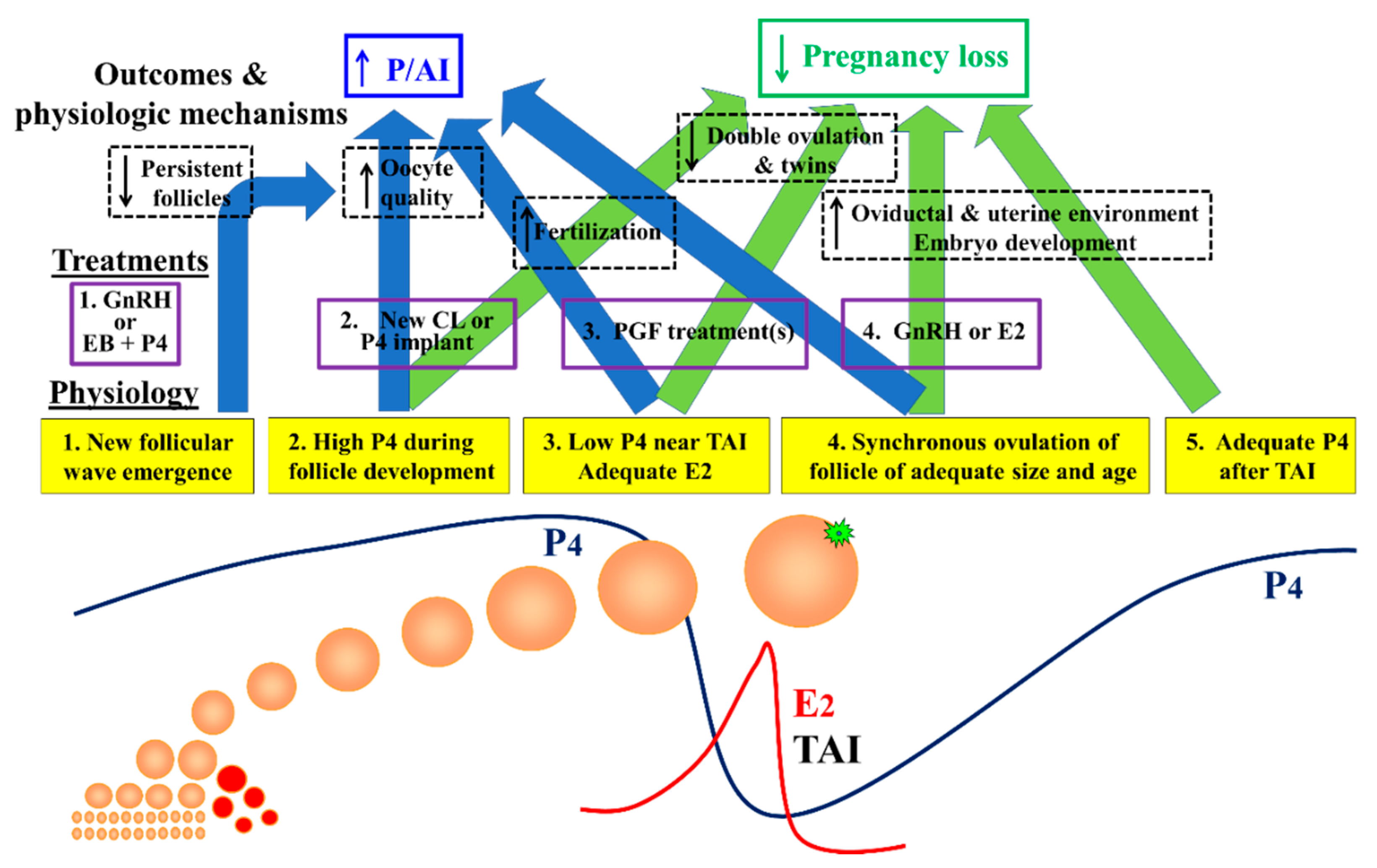

2. Five Key Physiologic Factors That Influence Fertility in Timed Artificial Insemination (TAI) Protocols

3. Hormonal Strategies to Improve TAI Protocols

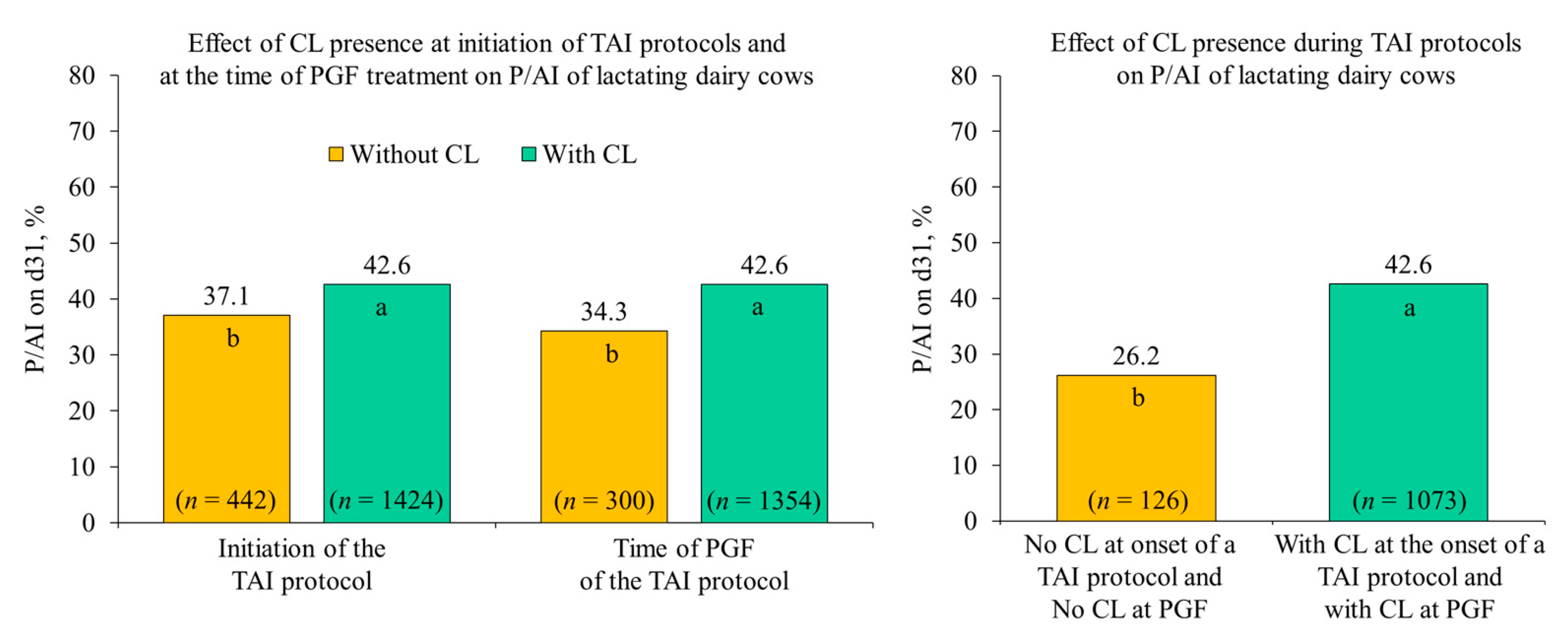

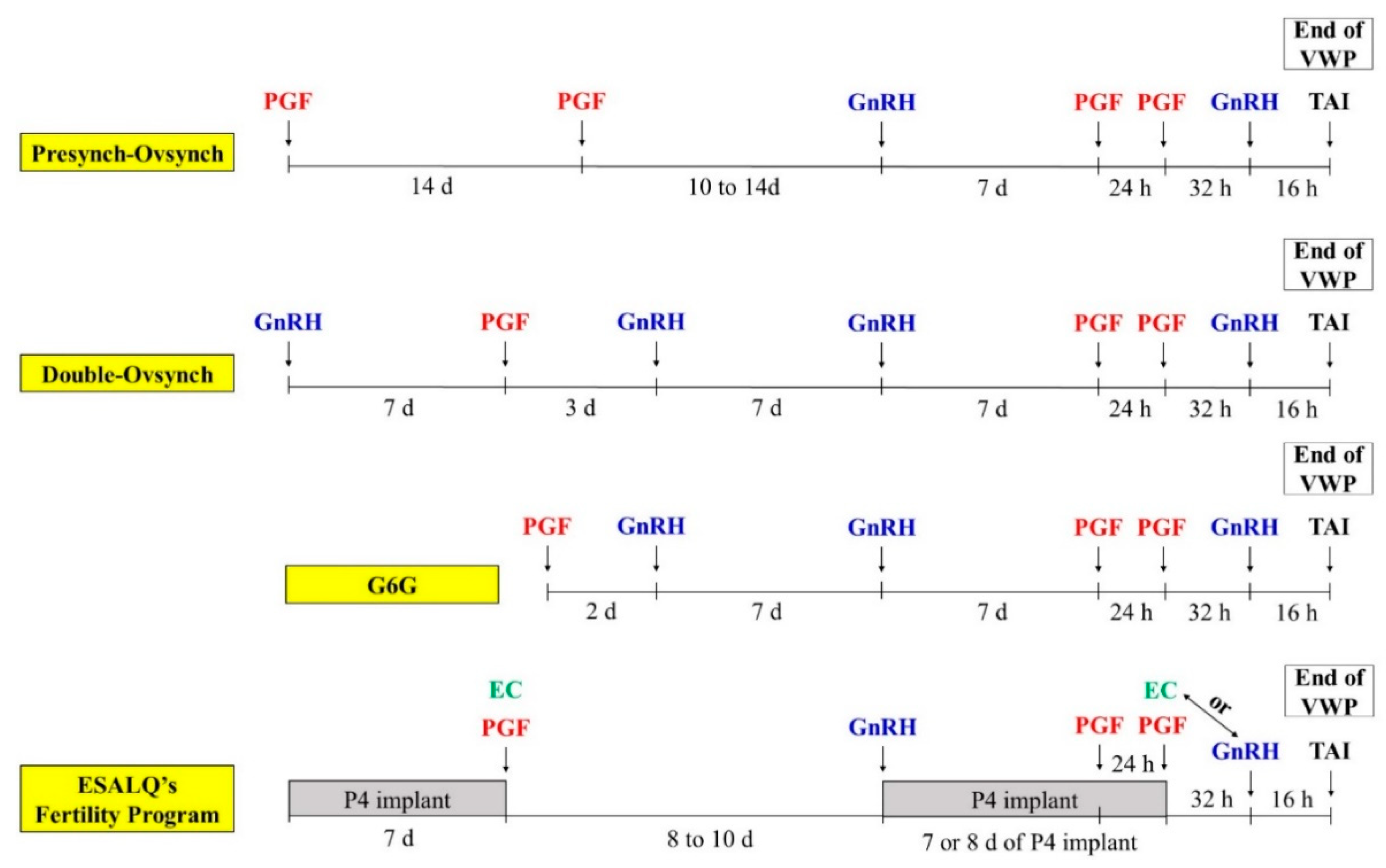

3.1. Hormonal Strategies to Initiate TAI Protocols

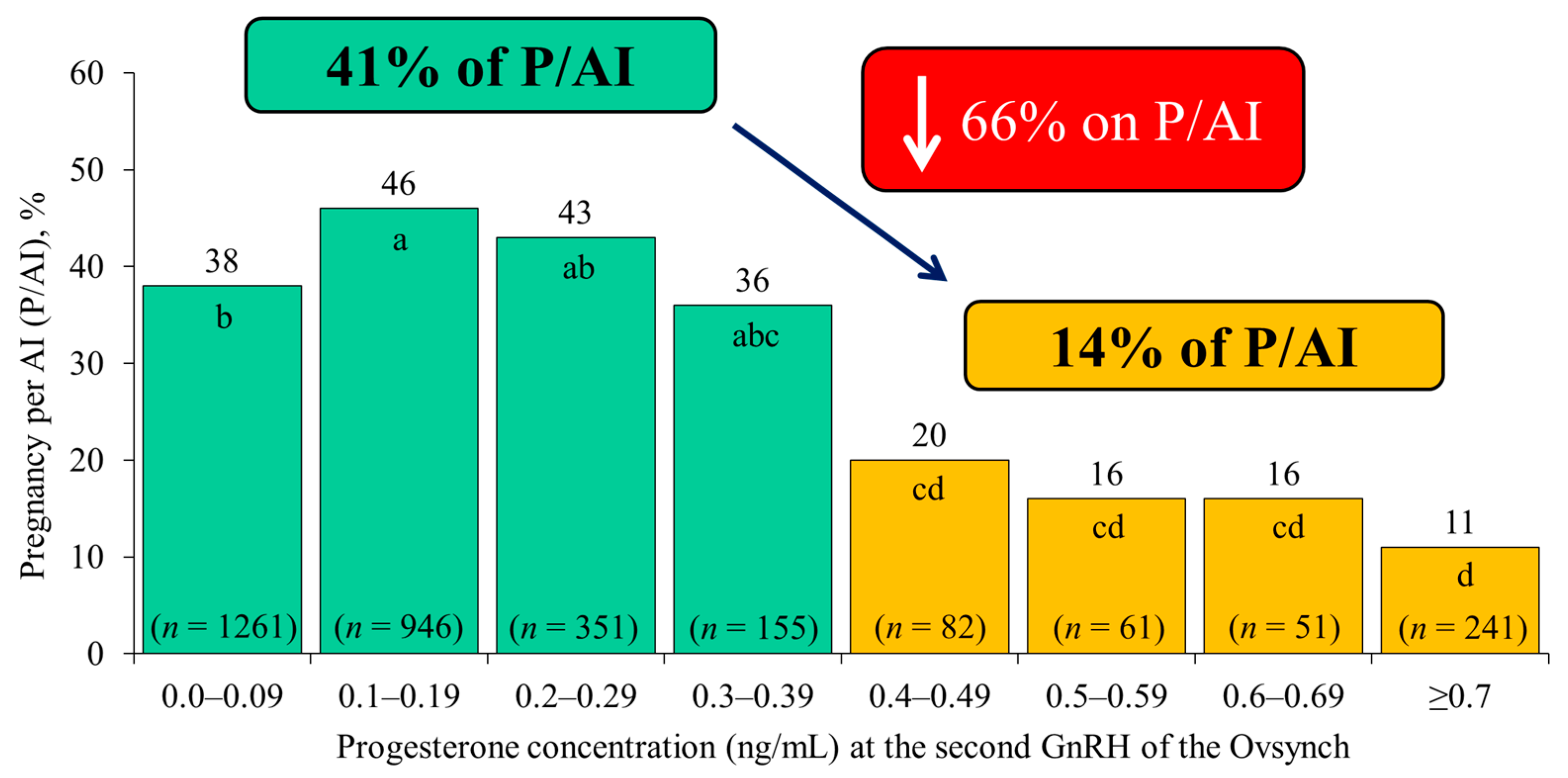

3.2. Intravaginal P4 Implants during TAI Protocols

3.3. Additional PGF Treatment during TAI Protocols

3.4. Strategies to Induce Final Ovulation in TAI Programs

4. Fertility Programs: First AI and Resynch Protocols with Improved Fertility

4.1. Protocols for First TAI That Produce Better Fertility than AI to Estrus

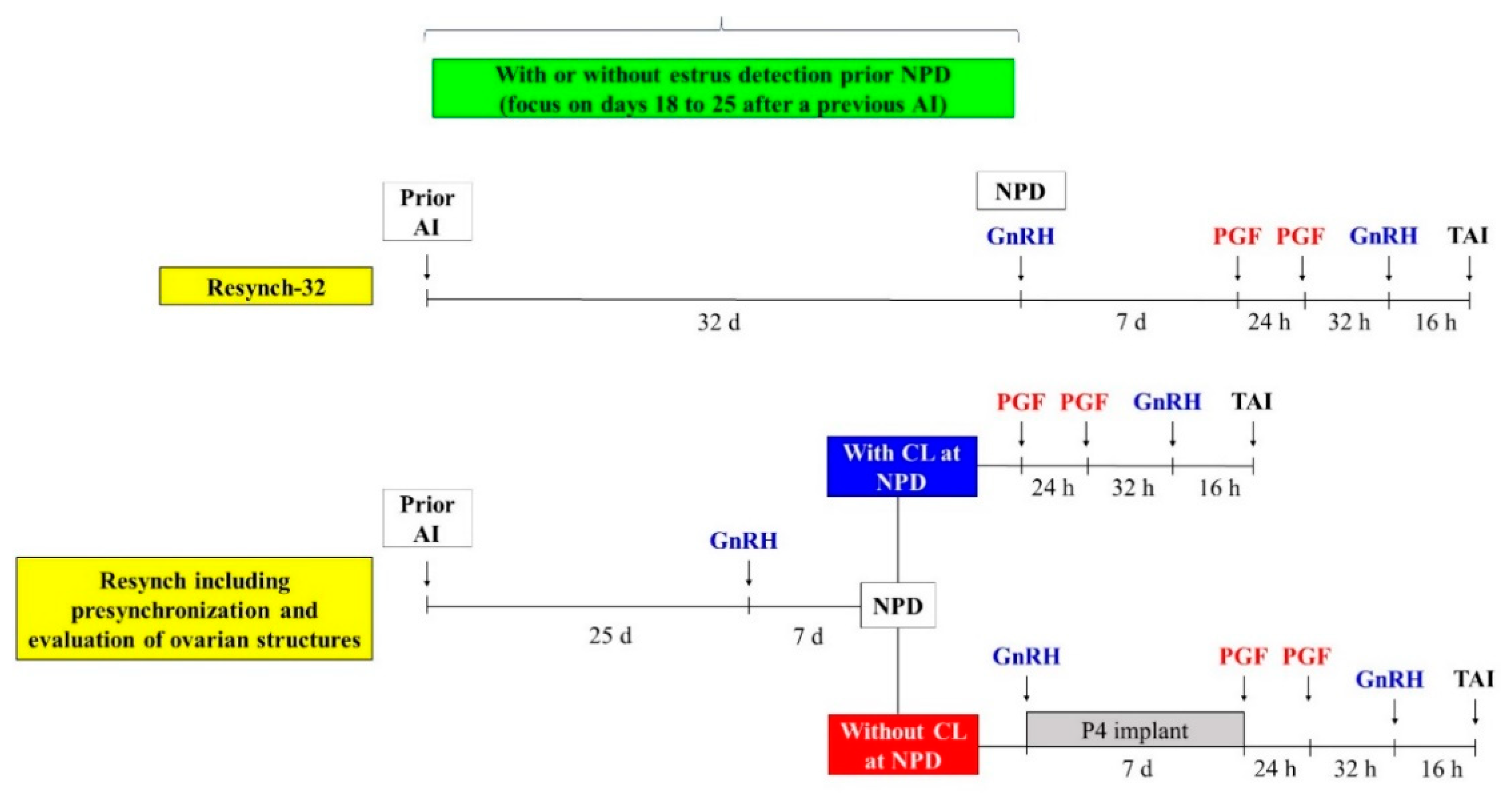

4.2. Reinsemination Strategies: Reducing the Interval between AI and Optimizing Fertility

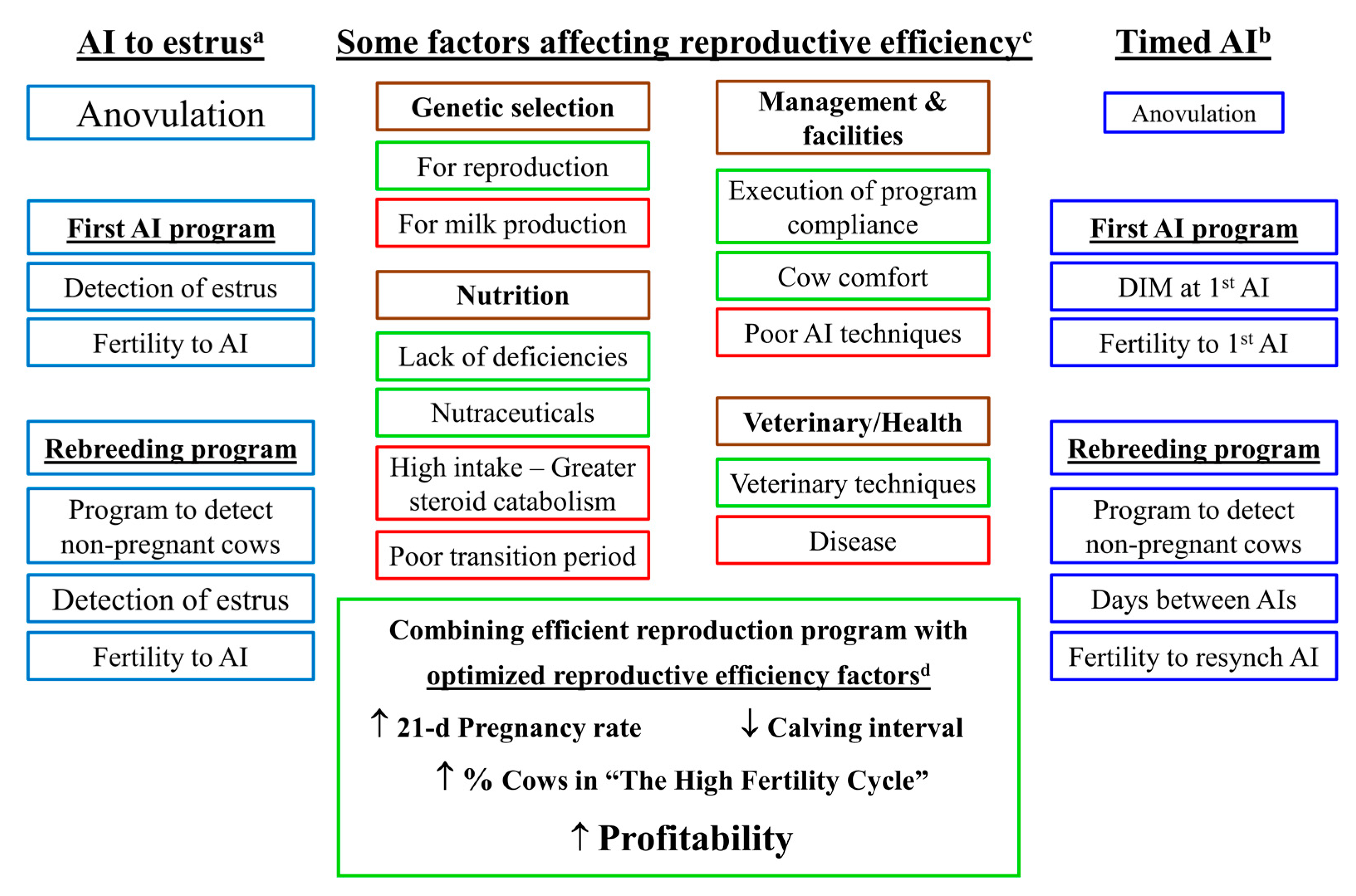

5. Key Factors That Alter Reproductive Efficiency in Dairy Herds

5.1. Genetic Selection for Health and Reproductive Traits

5.2. Optimizing Cow Comfort and Reducing Heat Stress

5.3. Importance of the Transition Period on Subsequent Fertility

5.4. Nutritional Strategies to Optimize Reproductive Performance

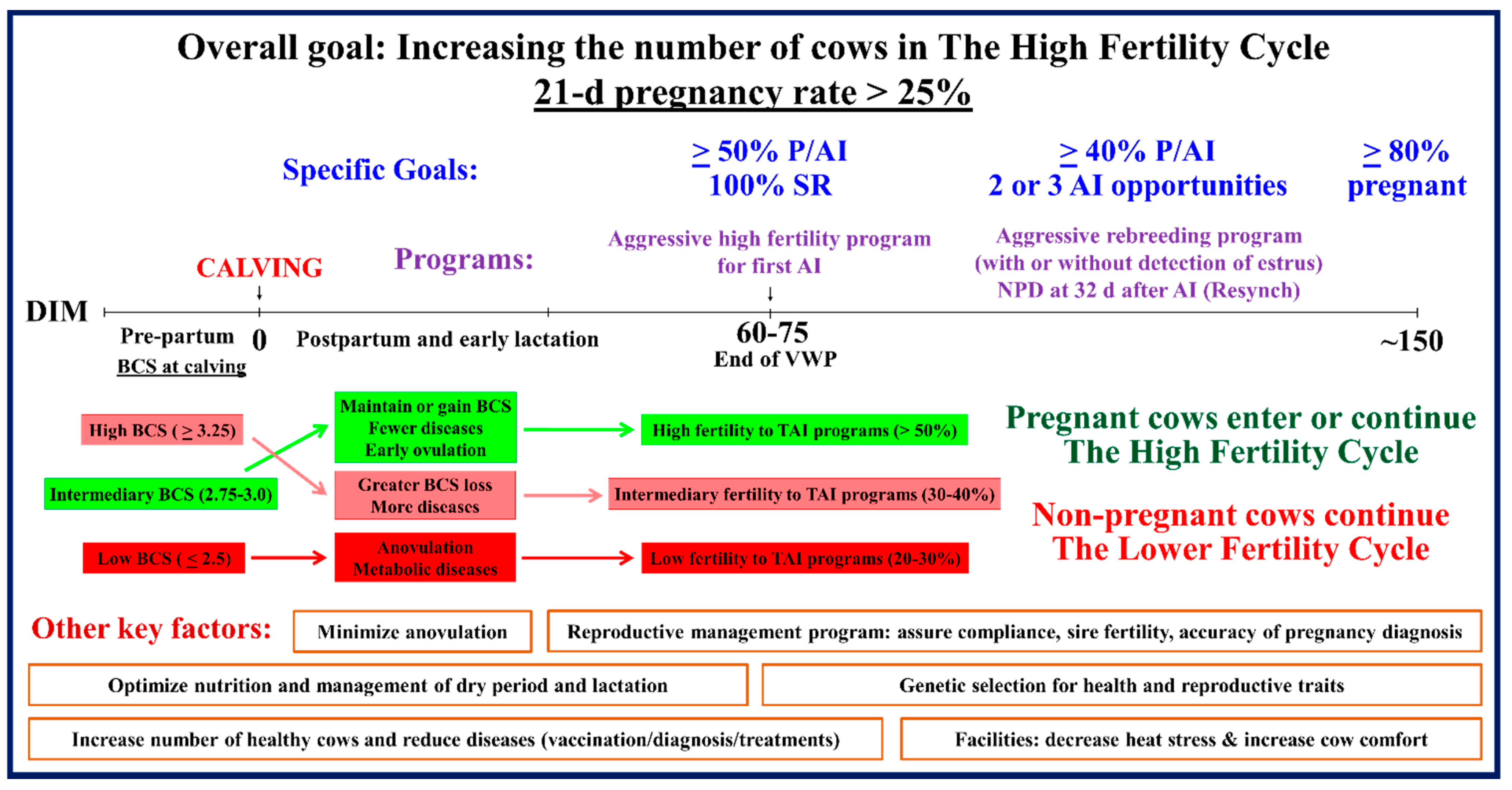

6. Implementation of Efficient Reproductive Management Programs: Achieving the High Fertility Cycle

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weigel, K.A.; VanRaden, P.; Norman, H.; Grosu, H. A 100-Year Review: Methods and impact of genetic selection in dairy cattle—From daughter–dam comparisons to deep learning algorithms. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 10234–10250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Ruiz, A.; Cole, J.B.; VanRaden, P.M.; Wiggans, G.R.; Ruiz-López, F.J.; Van Tassell, C. Changes in genetic selection differentials and generation intervals in US Holstein dairy cattle as a result of genomic selection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E3995–E4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, J.; VanRaden, P. Symposium review: Possibilities in an age of genomics: The future of selection indices. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 3686–3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucy, M. Symposium review: Selection for fertility in the modern dairy cow—Current status and future direction for genetic selection. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 3706–3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiltbank, M.; Pursley, J.R. The cow as an induced ovulator: Timed AI after synchronization of ovulation. Theriogenology 2014, 81, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, P.; Santos, V.; Giordano, J.; Wiltbank, M.; Fricke, P. Development of fertility programs to achieve high 21-day pregnancy rates in high-producing dairy cows. Theriogenology 2018, 114, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, J.; Fricke, P.; Wiltbank, M.; Cabrera, V. An economic decision-making support system for selection of reproductive management programs on dairy farms. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 6216–6232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, J.; Kalantari, A.; Fricke, P.; Wiltbank, M.; Cabrera, V. A daily herd Markov-chain model to study the reproductive and economic impact of reproductive programs combining timed artificial insemination and estrus detection. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 5442–5460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantari, A.; Cabrera, V. The effect of reproductive performance on the dairy cattle herd value assessed by integrating a daily dynamic programming model with a daily Markov chain model. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 6160–6170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvão, K.; Federico, P.; De Vries, A.; Schuenemann, G. Economic comparison of reproductive programs for dairy herds using estrus detection, timed artificial insemination, or a combination. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 2681–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, V. Economics of fertility in high-yielding dairy cows on confined TMR systems. Anim. Int. J. Anim. Biosci. 2014, 8, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overton, M.W.; Cabrera, V.E. Monitoring and quantifying the value of change in reproductive performance. In Large Dairy Herd Management, 3rd ed.; American Dairy Science Association: Champaign, IL, USA, 2017; pp. 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, A.; Li, M.; Fricke, P.; Cabrera, V.E. Short communication: Economic impact among 7 reproductive programs for lactating dairy cows, including a sensitivity analysis of the cost of hormonal treatments. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 5654–5661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vries, A.; Kaniyamattam, K. A review of simulation analyses of economics and genetics for the use of in-vitro produced embryos and artificial insemination in dairy herds. Anim. Reprod. 2020, 17, 20200020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, E.S.; Galvão, K.N.; Thatcher, W.W.; Santos, J.E.P. Economic aspects of applying reproductive technologies to dairy herds. Anim. Reprod. 2012, 9, 370–387. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, E.; Minela, T.; Pursley, J.R. The high-fertility cycle: How timely pregnancies in one lactation may lead to less body condition loss, fewer health issues, greater fertility, and reduced early pregnancy losses in the next lactation. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 5577–5587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, P.; Borsato, M.; Silva, F.; Prata, A.; Wiltbank, M.; Sartori, R. Increasing estradiol benzoate, pretreatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormone, and impediments for successful estradiol-based fixed-time artificial insemination protocols in dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 3826–3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revah, I.; Butler, W. Prolonged dominance of follicles and reduced viability of bovine oocytes. J. Reprod. Fertil. 1996, 106, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerri, R.L.A.; Rutigliano, H.M.; Chebel, R.C.; Santos, J.E.P. Period of dominance of the ovulatory follicle influences embryo quality in lactating dairy cows. Reproduction 2009, 137, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.; Gümen, A.; Silva, E.; Cunha, A.; Guenther, J.; Peto, C.; Caraviello, D.; Wiltbank, M. Supplementation with Estradiol-17β Before the Last Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Injection of the Ovsynch Protocol in Lactating Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 4623–4634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebel, R.C.; Al-Hassan, M.J.; Fricke, P.M.; Santos, J.E.P.; Lima, J.R.; Martel, C.A.; Stevenson, J.S.; Garcia, R.; Ax, R.L. Supplementation of progesterone via controlled internal drug release inserts during ovulation synchronization protocols in lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2010, 93, 922–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangsritavong, S.; Combs, D.; Sartori, R.; Armentano, L.; Wiltbank, M. High Feed Intake Increases Liver Blood Flow and Metabolism of Progesterone and Estradiol-17β in Dairy Cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2002, 85, 2831–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, R.; Rosa, G.J.M.; Wiltbank, M. Ovarian Structures and Circulating Steroids in Heifers and Lactating Cows in Summer and Lactating and Dry Cows in Winter. J. Dairy Sci. 2002, 85, 2813–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Schrick, F.N.; Butcher, R.L.; Inskeep, E.K. Fertilization rate and embryo development in relation to persistent follicles and peripheral estradiol-17-beta in beef cows. Biol. Reprod. 1994, 50, 65. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, A.F.; Mendonça, L.G.D.; Lopes, G.; Santos, J.E.P.; Perez, R.V.; Amstalden, M.; Correa-Calderón, A.; Chebel, R.C. Reduced progesterone concentration during growth of the first follicular wave affects embryo quality but has no effect on embryo survival post transfer in lactating dairy cows. Reproduction 2011, 141, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiltbank, M.; Carvalho, P.D.; Kaskin, A.; Hackbart, K.S.; Meschiatti, M.A.; Bastos, M.R.; Guenther, J.N.; Nascimento, A.B.; Herlihy, M.M.; Amundson, M.C.; et al. Effect of Progesterone Concentration During Follicle Development on Subsequent Ovulation, Fertilization, and Early Embryo Development in Lactating Dairy Cows. Biol. Reprod. 2011, 85, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisinotto, R.; Ribeiro, E.; Lima, F.; Martinez, N.; Greco, L.; Barbosa, L.; Bueno, P.; Scagion, L.; Thatcher, W.; Santos, J. Targeted progesterone supplementation improves fertility in lactating dairy cows without a corpus luteum at the initiation of the timed artificial insemination protocol. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 2214–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisinotto, R.; Castro, L.; Pansani, M.; Narciso, C.; Martinez, N.; Sinedino, L.; Pinto, T.; Van De Burgwal, N.; Bosman, H.; Surjus, R.; et al. Progesterone supplementation to lactating dairy cows without a corpus luteum at initiation of the Ovsynch protocol. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 2515–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, L.; Monteiro, P.; Surjus, R.; Drum, J.; Wiltbank, M.; Sartori, R. Progesterone-based fixed-time artificial insemination protocols for dairy cows: Gonadotropin-releasing hormone versus estradiol benzoate at initiation and estradiol cypionate versus estradiol benzoate at the end. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 9227–9237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consentini, C.E.C.; Silva, L.O.; Sartori, R. (Luiz de Queiroz College of Agriculture of University of São Paulo, Piracicaba, Brazil). Unpublished work. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, J.; Wang, D.; Mu, N.; Rossi, G.; Martini, A.; Martins, V.; Pursley, J.R. Level of circulating concentrations of progesterone during ovulatory follicle development affects timing of pregnancy loss in lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 10505–10525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, P.; Santos, V.; Fricke, H.; Hernandez, L.; Fricke, P. Effect of manipulating progesterone before timed artificial insemination on reproductive and endocrine outcomes in high-producing multiparous Holstein cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 7509–7521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, P.M.; Wiltbank, M.C. Effect of milk production on the incidence of double ovulation in dairy cows. Theriogenology 1999, 52, 1133–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, H.; Caraviello, D.; Satter, L.; Fricke, P.; Wiltbank, M. Relationship Between Level of Milk Production and Multiple Ovulations in Lactating Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2005, 88, 2783–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macmillan, K.; Kastelic, J.P.; Colazo, M. Update on Multiple Ovulations in Dairy Cattle. Animals 2018, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fricke, P. Twinning in Dairy Cattle. Prof. Anim. Sci. 2001, 17, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gatius, F.; Santolaria, P.; Yániz, J.; Rutllant, J.; López-Béjar, M. Factors affecting pregnancy loss from gestation Day 38 to 90 in lactating dairy cows from a single herd. Theriogenology 2002, 57, 1251–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Del-Río, N.; Colloton, J.D.; Fricke, P.M. Factors affecting pregnancy loss for single and twin pregnancies in a high-producing dairy herd. Theriogenology 2009, 71, 1462–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusveen, D.; Souza, A.; Wiltbank, M. Effects of additional prostaglandin F2α and estradiol-17β during Ovsynch in lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 1412–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, G.; Giordano, J.; Valenza, A.; Herlihy, M.; Guenther, J.; Wiltbank, M.; Fricke, P. Effect of timing of initiation of resynchronization and presynchronization with gonadotropin-releasing hormone on fertility of resynchronized inseminations in lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 3788–3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, P.; Wiltbank, M.; Fricke, P. Manipulation of progesterone to increase ovulatory response to the first GnRH treatment of an Ovsynch protocol in lactating dairy cows receiving first timed artificial insemination. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 8800–8813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colazo, M.; Helguera, I.L.; Behrouzi, A.; Ambrose, D.; Mapletoft, R. Relationship between circulating progesterone at timed-AI and fertility in dairy cows subjected to GnRH-based protocols. Theriogenology 2017, 94, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiltbank, M.C.; Baez, G.M.; Vasconcelos, J.L.M.; Pereira, M.; Souza, A.H.; Sartori, R.; Pursley, J.R. The physiology and impact on fertility of the period of proestrus in lactating dairy cows. Anim. Reprod. 2014, 11, 225–236. [Google Scholar]

- Heidari, F.; Dirandeh, E.; Pirsaraei, Z.A.; Colazo, M.G. Modifications of the G6G timed-AI protocol improved pregnancy per AI and reduced pregnancy loss in lactating dairy cows. Anim. Int. J. Anim. Biosci. 2017, 11, 2002–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barletta, R.; Carvalho, P.; Santos, V.; Melo, L.; Consentini, C.; Netto, A.; Fricke, P. Effect of dose and timing of prostaglandin F2α treatments during a Resynch protocol on luteal regression and fertility to timed artificial insemination in lactating Holstein cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 1730–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, A.B.; Souza, A.H.; Keskin, A.; Sartori, R.; Wiltbank, M. Lack of complete regression of the Day 5 corpus luteum after one or two doses of PGF2α in nonlactating Holstein cows. Theriogenology 2014, 81, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisinotto, R.; Pansani, M.; Castro, L.; Narciso, C.; Sinedino, L.; Martinez, N.; Carneiro, P.; Thatcher, W.; Santos, J. Effect of progesterone supplementation on fertility responses of lactating dairy cows with corpus luteum at the initiation of the Ovsynch protocol. Theriogenology 2015, 83, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.; Wiltbank, M.; Vasconcelos, J.L.M. Expression of estrus improves fertility and decreases pregnancy losses in lactating dairy cows that receive artificial insemination or embryo transfer. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 2237–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvão, K.N.; Santos, J.E.P.; Juchem, S.O.; Cerri, R.L.A.; Coscioni, A.C.; Villaseñor, M. Effect of addition of a progesterone intravaginal insert to a timed insemination protocol using estradiol cypionate on ovulation rate, pregnancy rate, and late embryonic loss in lactating dairy cows1. J. Anim. Sci. 2004, 82, 3508–3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, N.; Steibel, J.; Pursley, J.R. Optimizing Ovulation to First GnRH Improved Outcomes to Each Hormonal Injection of Ovsynch in Lactating Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 3413–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodi, S.; Cooke, R.; Fernandes, A.; Cappellozza, B.; Vasconcelos, J.; Cerri, R.L.A. Expression of estrus modifies the gene expression profile in reproductive tissues on Day 19 of gestation in beef cows. Theriogenology 2016, 85, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascieri, M.; Amann, R.P.; Hammerstedt, R.H. Adenine nucleotide changes at initiation of bull sperm motility. J. Biol. Chem. 1976, 251, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraenkel, L.; Cohn, F. Experimentelle untersuchungen des corpus luteum auf die insertion des eies (Theorie von Born). Anat. Anz. 1901, 20, 294–300. [Google Scholar]

- Magnus, V. Ovariets betydning for svangerskabet med saerligt hensyntil corpus luteum. Nor. Mag. Laegevidenskaben 1901, 62, 1138–1142. [Google Scholar]

- Herrick, J.B. Clinical observation of progesterone therapy in repeat breeding heifers. Vet. Med. 1953, 48, 489–490. [Google Scholar]

- Wiltbank, J.N.; Hawk, H.W.; Kidder, H.E.; Black, W.G.; Ulberg, L.C.; Casida, L.E. Effect of progesterone therapy on embryos survival in cows of lowered fertility. J. Dairy Sci. 1956, 39, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, G.; Lamming, G. The Influence of Progesterone During Early Pregnancy in Cattle. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 1999, 34, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, A.; Bender, R.; Souza, A.; Ayres, H.; Araujo, R.; Guenther, J.; Sartori, R.; Wiltbank, M. Effect of treatment with human chorionic gonadotropin on day 5 after timed artificial insemination on fertility of lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 2873–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besbaci, M.; Abdelli, A.; Minviel, J.J.; Belabdi, I.; Kaidi, R.; Raboisson, D. Association of pregnancy per artificial insemination with gonadotropin-releasing hormone and human chorionic gonadotropin administered during the luteal phase after artificial insemination in dairy cows: A meta-analysis. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 2006–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, J.; Portaluppi, M.A.; Tenhouse, D.E.; Lloyd, A.; Eborn, D.R.; Kacuba, S.; DeJarnette, J.M. Interventions After Artificial Insemination: Conception Rates, Pregnancy Survival, and Ovarian Responses to Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone, Human Chorionic Gonadotropin, and Progesterone. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, P.; Reynolds, L.P.; Redmer, D.A. Effect of human chorionic gonadotropin administered early in the estrous cycle on ovulation and subsequent luteal function in cows. J. Anim. Sci. 1993, 71, 1242–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.E.P.; Thatcher, W.W.; Pool, L.; Overton, M.W. Effect of human chorionic gonadotropin on luteal function and reproductive performance of high-producing lactating Holstein dairy cows. J. Anim. Sci. 2001, 79, 2881–2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, A.B.; Souza, A.; Guenther, J.N.; Costa, F.P.D.; Sartori, R.; Wiltbank, M. Effects of treatment with human chorionic gonadotrophin or intravaginal progesterone-releasing device after AI on circulating progesterone concentrations in lactating dairy cows. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2013, 25, 818–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lonergan, P.; Sánchez, J. Symposium review: Progesterone effects on early embryo development in cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 8698–8707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melo, L.; Monteiro, P.; Nascimento, A.; Drum, J.; Spies, C.; Prata, A.; Wiltbank, M.; Sartori, R. Follicular dynamics, circulating progesterone, and fertility in Holstein cows synchronized with reused intravaginal progesterone implants that were sanitized by autoclave or chemical disinfection. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 3554–3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consentini, C.E.C.; Silva, L.O.; Silva, T.J.B.; Folchini, N.P.; Gonzales, B.; Gonzales, J.; Wiltbank, M.C.; Sartori, R. Fertility of lactating Holstein cows initiating the FTAI protocol with estradiol benzoate or GnRH, and receiving or not GnRH 2 days later. Anim. Reprod. 2020, 17, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, M.; Rodrigues, A.; Martins, T.; Oliveira, W.; Silveira, P.; Wiltbank, M.; Vasconcelos, J.L.M. Timed artificial insemination programs during the summer in lactating dairy cows: Comparison of the 5-d Cosynch protocol with an estrogen/progesterone-based protocol. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 6904–6914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, M.; Wiltbank, M.; Barbosa, L.; Costa, W.; Carvalho, M.; Vasconcelos, J.L.M. Effect of adding a gonadotropin-releasing-hormone treatment at the beginning and a second prostaglandin F2α treatment at the end of an estradiol-based protocol for timed artificial insemination in lactating dairy cows during cool or hot seasons of the year. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 947–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, J.; Wiltbank, M.; Fricke, P.M.; Bas, S.; Pawlisch, R.; Guenther, J.N.; Nascimento, A.B. Effect of increasing GnRH and PGF2α dose during Double-Ovsynch on ovulatory response, luteal regression, and fertility of lactating dairy cows. Theriogenology 2013, 80, 773–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchardt, S.; Pohl, A.; Heuwieser, W. Luteal Presence and Ovarian Response at the Beginning of a Timed Artificial Insemination Protocol for Lactating Dairy Cows Affect Fertility: A Meta-Analysis. Animals 2020, 10, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, J.; Fricke, P.; Guenther, J.; Lopes, G.; Herlihy, M.; Nascimento, A.; Wiltbank, M. Effect of progesterone on magnitude of the luteinizing hormone surge induced by two different doses of gonadotropin-releasing hormone in lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 3781–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.O.; Alves, R.L.O.R.; Folchini, N.P.; Drum, J.N.; Madureira, G.; Consentini, C.E.C.; Motta, J.C.L.; Silva, M.A.; Cezar, A.M.; Wiltbank, M.C.; et al. Presence of CL and/or intravaginal progesterone insert affect ovulation and subsequent CL develop-ment after gonadorelin treatment. Anim. Reprod. 2019, 16, 646. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, L.O.; Motta, J.C.L.; Oliva, A.L.; Silva, M.A.; Silva, T.J.B.; Madureira, G.; Folchini, N.P.; Alves, R.L.O.R.; Consentini, C.E.C.; Galindez, J.P.A.; et al. Influence of the analogue and dose of GnRH on the LH release and ovulatory response in Bos indicus heifers and cows with high circulating progesterone. Anim. Reprod. 2020, 17, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Chenault, J.R. Effect of Fertirelin Acetate or Buserelin on Conception Rate at First or Second Insemination in Lactating Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1990, 73, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard-Hagen, N.; Lhermie, G.; Florentin, S.; Merle, D.; Frein, P.; Gayrard, V. Effect of gonadorelin, lecirelin, and buserelin on LH surge, ovulation, and progesterone in cattle. Theriogenology 2015, 84, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carneiro, T.O.; Neri, H.D.H.; Batista, E.O.S.; Valenza, A.; Souza, A.H. Improved conception results following GnRH treat-ment on day 2 of progesterone and estradiol-based synchronization protocols in high producing dairy cows. Anim. Reprod. 2017, 14, 709. [Google Scholar]

- Sartori, R.; Haughian, J.; Shaver, R.; Rosa, G.J.M.; Wiltbank, M. Comparison of Ovarian Function and Circulating Steroids in Estrous Cycles of Holstein Heifers and Lactating Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 905–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.; Sanches, C.; Guida, T.; Wiltbank, M.; Vasconcelos, J.L.M. Comparison of fertility following use of one versus two intravaginal progesterone inserts in dairy cows without a CL during a synchronization protocol before timed AI or timed embryo transfer. Theriogenology 2017, 89, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisinotto, R.; Lean, I.; Thatcher, W.; Santos, J. Meta-analysis of progesterone supplementation during timed artificial insemination programs in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 2472–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiltbank, M.; Baez, G.M.; Cochrane, F.; Barletta, R.V.; Trayford, C.R.; Joseph, R.T. Effect of a second treatment with prostaglandin F2α during the Ovsynch protocol on luteolysis and pregnancy in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 8644–8654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.; Carvalho, P.; Maia, C.; Carneiro, B.; Valenza, A.; Crump, P.; Fricke, P. Adding a second prostaglandin F2α treatment to but not reducing the duration of a PRID-Synch protocol increases fertility after resynchronization of ovulation in lactating Holstein cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 3869–3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchardt, S.; Pohl, A.; Carvalho, P.; Fricke, P.; Heuwieser, W. Short communication: Effect of adding a second prostaglandin F2α injection during the Ovsynch protocol on luteal regression and fertility in lactating dairy cows: A meta-analysis. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 8566–8571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pursley, J.; Mee, M.; Wiltbank, M. Synchronization of ovulation in dairy cows using PGF2α and GnRH. Theriogenology 1995, 44, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancarci, S.; Jordan, E.; Risco, C.; Schouten, M.; Lopes, F.L.; Moreira, F.; Thatcher, W. Use of Estradiol Cypionate in a Presynchronized Timed Artificial Insemination Program for Lactating Dairy Cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2002, 85, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.; Viechnieski, S.; Lima, F.A.; Silva, F.F.; Araújo, R.; Bo, G.A.; Wiltbank, M.; Baruselli, P.S. Effects of equine chorionic gonadotropin and type of ovulatory stimulus in a timed-AI protocol on reproductive responses in dairy cows. Theriogenology 2009, 72, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consentini, C.E.C.; Melo, L.F.; Motta, J.C.L.; Alves, R.L.O.R.; Silva, L.O.; Madureira, G.; Wiltbank, M.C.; Sartori, R. Strate-gies for induction of ovulation for first fixed-time AI postpartum in lactating dairy cows submitted to a novel presynchronization protocol. Anim. Reprod. 2019, 16, 557. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, F.; Orlandi, C.; Risco, C.; Mattos, R.; Lopes, F.; Thatcher, W. Effects of Presynchronization and Bovine Somatotropin on Pregnancy Rates to a Timed Artificial Insemination Protocol in Lactating Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2001, 84, 1646–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Zarkouny, S.; Cartmill, J.; Hensley, B.; Stevenson, J. Pregnancy in Dairy Cows After Synchronized Ovulation Regimens with or without Presynchronization and Progesterone. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 1024–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navanukraw, C.; Redmer, D.; Reynolds, L.; Kirsch, J.; Grazul-Bilska, A.; Fricke, P. A Modified Presynchronization Protocol Improves Fertility to Timed Artificial Insemination in Lactating Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 1551–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, J.; Thomas, M.; Catucuamba, G.; Curler, M.; Wijma, R.; Stangaferro, M.; Masello, M. Effect of extending the interval from Presynch to initiation of Ovsynch in a Presynch-Ovsynch protocol on fertility of timed artificial insemination services in lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 746–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebel, R.; Santos, J.E.P.; Cerri, R.; Rutigliano, H.; Bruno, R. Reproduction in Dairy Cows Following Progesterone Insert Presynchronization and Resynchronization Protocols. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 4205–4219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, P.; Giordano, J.; Valenza, A.; Lopes, G.; Amundson, M.; Carvalho, P. Reproductive performance of lactating dairy cows managed for first service using timed artificial insemination with or without detection of estrus using an activity-monitoring system. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 2771–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchardt, S.; Haimerl, P.; Heuwieser, W. Effect of insemination after estrous detection on pregnancy per artificial insemination and pregnancy loss in a Presynch-Ovsynch protocol: A meta-analysis. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 2248–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Pursley, J. Fertility of Lactating Dairy Cows Treated with Ovsynch after Presynchronization Injections of PGF2α and GnRH. J. Dairy Sci. 2002, 85, 2403–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, M.R.; Martins, J.P.N.; Ahmad, N.; Nobis, K.; Pursley, J.R. Presynchronization of lactating dairy cows with PGF 2α and GnRH simultaneously, 7 days before Ovsynch have similar outcomes compared to G6G. Theriogenology 2016, 86, 1607–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.H.; Ayres, H.; Ferreira, R.M.; Wiltbank, M.C. A new presynchronization system (Double-Ovsynch) increases fertility at first postpartum timed AI in lactating dairy cows. Theriogenology 2008, 70, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, H.; Ferreira, R.; Cunha, A.; Araújo, R.; Wiltbank, M. Double-Ovsynch in high-producing dairy cows: Effects on progesterone concentrations and ovulation to GnRH treatments. Theriogenology 2013, 79, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herlihy, M.; Giordano, J.; Souza, A.; Ayres, H.; Ferreira, R.; Keskin, A.; Nascimento, A.; Guenther, J.; Gaska, J.; Kacuba, S.; et al. Presynchronization with Double-Ovsynch improves fertility at first postpartum artificial insemination in lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 7003–7014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.; Carvalho, P.; Maia, C.; Carneiro, B.; Valenza, A.; Fricke, P. Fertility of lactating Holstein cows submitted to a Double-Ovsynch protocol and timed artificial insemination versus artificial insemination after synchronization of estrus at a similar day in milk range. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 8507–8517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebel, R.C.; Scanavez, A.; Silva, P.; Moraes, J.; Mendonça, L.; Lopes, G., Jr. Evaluation of presynchronized resynchronization protocols for lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 1009–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, R.; Moraes, J.; Hernández-Rivera, J.; Lager, K.; Silva, P.; Scanavez, A.; Mendonça, L.; Chebel, R.; Bilby, T. Effect of an Ovsynch56 protocol initiated at different intervals after insemination with or without a presynchronizing injection of gonadotropin-releasing hormone on fertility in lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, J.; Stangaferro, M.; Wijma, R.; Chandler, W.; Watters, R. Reproductive performance of dairy cows managed with a program aimed at increasing insemination of cows in estrus based on increased physical activity and fertility of timed artificial inseminations. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 2488–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, P.; Caraviello, D.Z.; Weigel, K.A.; Welle, M.L. Fertility of Dairy Cows after Resynchronization of Ovulation at Three Intervals Following First Timed Insemination. J. Dairy Sci. 2003, 86, 3941–3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisinotto, R.; Ribeiro, E.; Martins, L.; Marsola, R.; Greco, L.; Favoreto, M.; Risco, C.; Thatcher, W.; Santos, J. Effect of interval between induction of ovulation and artificial insemination (AI) and supplemental progesterone for resynchronization on fertility of dairy cows subjected to a 5-d timed AI program. J. Dairy Sci. 2010, 93, 5798–5808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, J.; Wiltbank, M.; Guenther, J.; Pawlisch, R.; Bas, S.; Cunha, A.; Fricke, P. Increased fertility in lactating dairy cows resynchronized with Double-Ovsynch compared with Ovsynch initiated 32 d after timed artificial insemination. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilby, T.; Bruno, R.; Lager, K.; Chebel, R.; Moraes, J.; Fricke, P.; Lopes, G.; Giordano, J.; Santos, J.; Lima, F.; et al. Supplemental progesterone and timing of resynchronization on pregnancy outcomes in lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 7032–7042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijma, R.; Stangaferro, M.; Masello, M.; Granados, G.; Giordano, J. Resynchronization of ovulation protocols for dairy cows including or not including gonadotropin-releasing hormone to induce a new follicular wave: Effects on re-insemination pattern, ovarian responses, and pregnancy outcomes. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 7613–7625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijma, R.; Pérez, M.; Masello, M.; Stangaferro, M.; Giordano, J. A resynchronization of ovulation program based on ovarian structures present at nonpregnancy diagnosis reduced time to pregnancy in lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 1697–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauls-Hiesterman, J.; Voelz, B.; Stevenson, J. A shortened resynchronization treatment for dairy cows after a nonpregnancy diagnosis. Theriogenology 2020, 141, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, S.; Mendonça, L.; Lopes, G.; Rivera, F.; Guagnini, F.; Chebel, R.; Bilby, T. Resynchronization strategies to improve fertility in lactating dairy cows utilizing a presynchronization injection of GnRH or supplemental progesterone: I. Pregnancy rates and ovarian responses. J. Dairy Sci. 2010, 93, 4086–4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, J.; Thomas, M.; Catucuamba, G.; Curler, M.; Masello, M.; Stangaferro, M.; Wijma, R. Reproductive management strategies to improve the fertility of cows with a suboptimal response to resynchronization of ovulation. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 2967–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, J.; Spurlock, D.M. Improving production efficiency through genetic selection. In Large Dairy Herd Management, 3rd ed.; American Dairy Science Association: Champaign, IL, USA, 2017; pp. 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, F.S.; Silvestre, F.; Peñagaricano, F.; Thatcher, W. Early genomic prediction of daughter pregnancy rate is associated with improved reproductive performance in Holstein dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 3312–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitko, E.M.; Pérez, E.M.; Granados, G.E.; Masello, M.; Dicroce, F.; McNeel, A.; Weigel, D.; Giordano, J.O. Genetic merit for fertility and type of reproductive management strategy affected the reproductive performance of primiparous lactating Holstein cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 115. [Google Scholar]

- Schüller, L.-K.; Burfeind, O.; Heuwieser, W. Effect of short- and long-term heat stress on the conception risk of dairy cows under natural service and artificial insemination breeding programs. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 2996–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consentini, C.E.C.; Mingoti, R.D.; Germano, R.; Souza, A.H.; Baruselli, P.S.; Sartori, R. Impact of rectal temperature, temper-ature-humidity-index and season of year on pregnancy per AI during a reproductive year of a commercial dairy herd. Anim. Reprod. 2018, 15, 319. [Google Scholar]

- Baruselli, P.; Ferreira, R.M.; Vieira, L.M.; Souza, A.H.; Bó, G.A.; Rodrigues, C.A. Use of embryo transfer to alleviate infertility caused by heat stress. Theriogenology 2020, 155, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almoosavi, S.S.; Ghoorchi, T.; Naserian, A.; Khanaki, H.; Drackley, J.; Ghaffari, M. Effects of late-gestation heat stress independent of reduced feed intake on colostrum, metabolism at calving, and milk yield in early lactation of dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polsky, L.; Von Keyserlingk, M.A. Invited review: Effects of heat stress on dairy cattle welfare. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 8645–8657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitali, A.; Felici, A.; Lees, A.M.; Giacinti, G.; Maresca, C.; Bernabucci, U.; Gaughan, J.B.; Nardone, A.; Lacetera, N. Heat load increases the risk of clinical mastitis in dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 8378–8387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaPorta, J.; Ferreira, F.; Ouellet, V.; Dado-Senn, B.; Almeida, A.K.; De Vries, A.; Dahl, G. Late-gestation heat stress impairs daughter and granddaughter lifetime performance. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 7555–7568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, Z.; Arav, A.; Bor, A.; Zeron, Y.; Braw-Tal, R.; Wolfenson, D. Improvement of quality of oocytes collected in the autumn by enhanced removal of impaired follicles from previously heat-stressed cows. Reproduction 2001, 122, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Júnior, J.D.S.; Pires, M.D.F.; De Sá, W.; Ferreira, A.D.M.; Viana, J.; Camargo, L.; Ramos, A.; Folhadella, I.; Polisseni, J.; De Freitas, C.; et al. Effect of maternal heat-stress on follicular growth and oocyte competence in Bos indicus cattle. Theriogenology 2008, 69, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.M.; Ayres, H.; Chiaratti, M.R.; Ferraz, M.L.; Araujo, A.B.; Rodrigues, C.A.; Watanabe, Y.F.; Vireque, A.A.; Joaquim, D.C.; Smith, L.C.; et al. The low fertility of repeat-breeder cows during summer heat stress is related to a low oocyte competence to develop into blastocysts. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 2383–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correa-Calderon, A.; Armstrong, D.; Ray, D.; DeNise, D.; Enns, M.; Howison, C. Thermoregulatory responses of Holstein and Brown Swiss Heat-Stressed dairy cows to two different cooling systems. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2004, 48, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendall, P.E.; Verkerk, G.A.; Webster, J.R.; Tucker, C.B. Sprinklers and shade cool cows and reduce insect-avoidance behavior in pasture-based dairy systems. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 3671–3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flamenbaum, I.; Galon, N. Management of heat stress to improve fertility in dairy cows in Israel. J. Reprod. Dev. 2010, 56, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, A. Estimates of heat stress relief needs for Holstein dairy cows. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 8, 1377–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M.; Schütz, K.E.; Tucker, C.B. Dairy cows use and prefer feed bunks fitted with sprinklers. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 5035–5045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M.; Schütz, K.E.; Tucker, C.B. Cooling cows efficiently with water spray: Behavioral, physiological, and production responses to sprinklers at the feed bunk. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 4607–4618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tresoldi, G.; Schütz, K.E.; Tucker, C.B. Cooling cows with sprinklers: Spray duration affects the physiological responses to heat load. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 4412–4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Bisinotto, R.S.; Ribeiro, E.S.; Lima, F.S.; Greco, L.F.; Staples, C.R.; Thatcher, W.W. Applying nutrition and physiology to improve reproduction in dairy cattle. Soc. Reprod. Rertility Suppl. 2010, 67, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.; Peñagaricano, F.; Santos, J.; Devries, T.; McBride, B.; Ribeiro, E. Long-term effects of postpartum clinical disease on milk production, reproduction, and culling of dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 11701–11717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, P.D.; Souza, A.H.; Amundson, M.C.; Hackbart, K.S.; Fuenzalida, M.J.; Herlihy, M.M.; Ayres, H.; Dresch, A.R.; Vieira, L.M.; Guenther, J.N.; et al. Relationships between fertility and postpartum changes in body condition and body weight in lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 3666–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barletta, R.; Filho, M.M.; Carvalho, P.; Del Valle, T.; Netto, A.; Rennó, F.; Mingoti, R.; Gandra, J.; Mourão, G.; Fricke, P.; et al. Association of changes among body condition score during the transition period with NEFA and BHBA concentrations, milk production, fertility, and health of Holstein cows. Theriogenology 2017, 104, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, D.; Arnold, L.; Stowe, C.; Harmon, R.; Bewley, J. Estimating US dairy clinical disease costs with a stochastic simulation model. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 1472–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godden, S.M.; Stewart, S.C.; Fetrow, J.F.; Rapnicki, P.; Cady, R.; Weiland, W.; Spencer, H.; Eicker, S.W. The relationship between herd rbST supplementation and other factors and risk for removal for cows in Minnesota Holstein dairy herds. In Procedures of Four-State Nutrition Conference; MWPS-4SD16; MidWest Plan Service: Ames, IA, USA; LaCrosse, WI, USA, 2003; pp. 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, M.; Reneau, J.; Chester-Jones, H.; Chebel, R.; Endres, M. Cow- and herd-level risk factors for on-farm mortality in Midwest US dairy herds. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 4401–4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, R.; Kelton, D.F.; Duffield, T.F.; Leslie, K.E.; Walton, J.S.; Leblanc, S.J. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Postpartum Anovulatory Condition in Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, P.; Gonzales, B.; Drum, J.; Santos, J.; Wiltbank, M.; Sartori, R. Prevalence and risk factors related to anovular phenotypes in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebel, R.C.; Mendonça, L.; Baruselli, P.S. Association between body condition score change during the dry period and postpartum health and performance. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 4595–4614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, H.; Kanitz, F.; Moreira, V.; Satter, L.; Wiltbank, M. Reproductive Performance of Dairy Cows Fed Two Concentrations of Phosphorus. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, H.; Wu, Z.; Satter, L.; Wiltbank, M. Effect of dietary phosphorus concentration on estrous behavior of lactating dairy cows. Theriogenology 2004, 61, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, L.; Luchini, D.; Devillard, E.; Hansen, P.J. Methionine Requirements for the Preimplantation Bovine Embryo. J. Reprod. Dev. 2010, 56, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, F.C.; LeBlanc, S.J.; Murphy, M.R.; Drackley, J.K. Prepartum nutritional strategy affects reproductive performance in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 5859–5871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontes, G.C.; Monteiro, P.L.; Prata, A.B.; Guardieiro, M.M.; Pinto, D.A.; Fernandes, G.O.; Wiltbank, M.C.; Santos, J.E.; Sartori, R. Effect of injectable vitamin E on incidence of retained fetal membranes and reproductive performance of dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 2437–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinhardt, T.A.; Lippolis, J.D.; McCluskey, B.J.; Goff, J.P.; Horst, R.L. Prevalence of subclinical hypocalcemia in dairy herds. Vet. J. 2011, 188, 122–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, N.; Risco, C.A.; Lima, F.S.; Bisinotto, R.S.; Greco, L.F.; Ribeiro, E.S.; Maunsell, F.; Galvão, K.; Santos, J.E. Evaluation of peripartal calcium status, energetic profile, and neutrophil function in dairy cows at low or high risk of developing uterine disease. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 7158–7172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, E.M.; Arís, A.; Bach, A. Associations between subclinical hypocalcemia and postparturient diseases in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 7427–7434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venjakob, P.L.; Pieper, L.; Heuwieser, W.; Borchardt, S. Association of postpartum hypocalcemia with early-lactation milk yield, reproductive performance, and culling in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 100, 9396–9405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Lean, I.J.; Golder, H.; Block, E. Meta-analysis of the effects of prepartum dietary cation-anion difference on performance and health of dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 2134–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, U.; Zenobi, M.G.; Staples, C.R.; Santos, J. Meta-analysis of the effects of supplemental rumen-protected choline during the transition period on performance and health of parous dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 282–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenobi, M.G.; Gardinal, R.; Zuniga, J.E.; Mamedova, L.K.; Driver, J.P.; Barton, B.A.; Santos, J.; Staples, C.R.; Nelson, C.D. Effect of prepartum energy intake and supplementation with ruminally protected choline on innate and adaptive immunity of multiparous Holstein cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 2200–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, F.S.; Sá Filho, M.F.; Greco, L.F.; Santos, J.E. Effects of feeding rumen-protected choline on incidence of diseases and reproduction of dairy cows. Vet. J. 2012, 193, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, S.; Sugimoto, M.; Kume, S. Importance of Methionine Metabolism in Morula-to-blastocyst Transition in Bovine Preimplantation Embryos. J. Reprod. Dev. 2012, 58, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peñagaricano, F.; Souza, A.H.; Carvalho, P.D.; Driver, A.M.; Gambra, R.; Kropp, J.; Hackbart, K.S.; Luchini, D.; Shaver, R.D.; Wiltbank, M.; et al. Effect of Maternal Methionine Supplementation on the Transcriptome of Bovine Preimplantation Embryos. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta, D.; Denicol, A.; Tribulo, P.; Rivelli, M.; Skenandore, C.; Zhou, Z.; Luchini, D.; Corrêa, M.; Hansen, P.; Cardoso, F. Effects of rumen-protected methionine and choline supplementation on the preimplantation embryo in Holstein cows. Theriogenology 2016, 85, 1669–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toledo, M.Z.; Baez, G.M.; Garcia-Guerra, A.; Lobos, N.E.; Guenther, J.N.; Trevisol, E.; Luchini, D.; Shaver, R.D.; Wiltbank, M.C. Effect of feeding rumen-protected methionine on productive and reproductive performance of dairy cows. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinedino, L.D.P.; Honda, P.M.; Souza, L.R.L.; Lock, A.L.; Boland, M.P.; Staples, C.R.; Thatcher, W.W.; Santos, J. Effects of supplementation with docosahexaenoic acid on reproduction of dairy cows. Reproduction 2017, 153, 707–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | n | EB on d0 of the TAI Protocol | GnRH on d0 of the TAI Protocol | Difference 1 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [67] Pereira et al. (2013) 2 | 1190 | 43.3% | 72.5% | 29.1% | <0.01 |

| [68] Pereira et al. (2015) 3 | 1474 | 55.4% | 69.5% | 14.1% | <0.01 |

| [29] Melo et al. (2016) 3 | 417 | 57.3% | 76.4% | 19.0% | <0.01 |

| [66] Consentini et al. (2020) 3 | 369 | 56.6% | 89.8% | 33.2% | <0.01 |

| Total | 3450 | 52.0% | 74.3% | 22.2% | <0.001 |

| Study | n | Only EB on d0 | GnRH on d0 | Difference 1 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [68] Pereira et al. (2015) | 1808 | 30.7% | 36.8% | 5.9% (19.2%) | <0.05 2 |

| [29] Melo et al. (2016) | 1035 | 33.7% | 38.2% | 4.5% (13.4%) | 0.07 3 |

| [76] Carneiro et al. (2017) | 871 | 28.7% | 38.2% | 9.5% (33.1%) | <0.05 4 |

| 28.7% | 34.5% | 5.8% (20.2%) | 0.10 2 | ||

| [66] Consentini et al. (2020) | 943 | 37.5% | 42.8% | 5.3% (14.1%) | NS 3 |

| 37.5% | 42.0% | 4.5% (12.0%) | NS 5 | ||

| 37.5% | 44.3% | 6.8% (18.1%) | <0.05 4 | ||

| Total | 4657 | 33.5% | 39.5% | 6.1% (18.2%) | <0.05 |

| Item | 1 PGF during Ovsynch | 2 PGF during Ovsynch | Range | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete luteolysis at the end of Ovsynch, % (n/n) | 83.5 (788/944) | 95.1 (867/912) | 6–14 | <0.001 |

| P/AI, % (n/n) | 34.0 (915/2689) | 38.6 (1029/2667) | 3–9 | <0.001 |

| Item | Strategy to Induce Final Ovulation in the TAI Protocol | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC | EC/G | G | ||

| P/AI on d31, % (n/n) | 42.5 (99/233) | 43.0 (95/221) | 42.8 (89/208) | 0.45 |

| P/AI on d60, % (n/n) | 37.1 (86/232) | 37.5 (81/216) | 33.7 (69/205) | 0.42 |

| Pregnancy loss, % (n/n) | 12.2 (12/98) A | 10.0 (9/90) A | 19.8 (17/86) B | 0.09 |

| Item | Strategy for First AI | Difference, % (p-Value) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Double-Ovsynch | Estrus | ||

| No. of cows | 294 | 284 | |

| Submission rate, % (n/n) | 100.0 (294/294) | 77.5 (220/284) | 29 (<0.01) |

| P/AI at 33 d, % (n/n) | 49.0 (144/294) | 38.6 (85/220) | 27 (002) |

| Pregnant cows at 33 d, % (n/n) | 49.0 (144/294) | 29.9 (85/284) | 64 (<0.01) |

| P/AI at 63 d, % (n/n) | 44.6 (131/294) | 36.4 (80/220) | 23 (0.05) |

| Pregnant cows at 63 d, % (n/n) | 44.6 (131/294) | 28.2 (80/284) | 58 (<0.01) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cardoso Consentini, C.E.; Wiltbank, M.C.; Sartori, R. Factors That Optimize Reproductive Efficiency in Dairy Herds with an Emphasis on Timed Artificial Insemination Programs. Animals 2021, 11, 301. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11020301

Cardoso Consentini CE, Wiltbank MC, Sartori R. Factors That Optimize Reproductive Efficiency in Dairy Herds with an Emphasis on Timed Artificial Insemination Programs. Animals. 2021; 11(2):301. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11020301

Chicago/Turabian StyleCardoso Consentini, Carlos Eduardo, Milo Charles Wiltbank, and Roberto Sartori. 2021. "Factors That Optimize Reproductive Efficiency in Dairy Herds with an Emphasis on Timed Artificial Insemination Programs" Animals 11, no. 2: 301. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11020301

APA StyleCardoso Consentini, C. E., Wiltbank, M. C., & Sartori, R. (2021). Factors That Optimize Reproductive Efficiency in Dairy Herds with an Emphasis on Timed Artificial Insemination Programs. Animals, 11(2), 301. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11020301