1. Introduction

Discussions about the treatment and welfare of non-human animals (hereafter ‘animals’) usually concern livestock, companion animals, laboratory animals, or large wild animals. However, the range of human-animal interactions includes many more animals. These animals are neither wild, nor domesticated. Living their lives amidst humans, between nature, and culture, these animals, such as commensal rats, house mice, and pigeons can be considered

liminal [

1]. For the purpose of, e.g., food safety, human and animal health, hygiene, and safety of stables, all over the world, unspecified but large numbers of rats (

Rattus norvegicus [

2] and

Rattus rattus [

3]) and house mice (

Mus musculus [

3]) are killed (with several methods inflicting significant levels of suffering [

4]) because they are perceived as ‘pests’ or ‘vermin’. It is striking that once labeled as a pest animal, discussions on moral status and welfare seem to disappear from both the scientific and public debate. In the relatively small amount of papers on the treatment of these animals, authors point out the inconsistency in the treatment of different animals depending on the context [

5,

6]. For instance, within the current legislation in most Western societies, people have comparatively a lot of freedom to decide how to deal with these liminal rodents that do not differ in their capacities to suffer compared to rats and mice in other practices, such as the laboratory or as pets [

7]. In scientific research for the production of rat poison, a rat will be monitored and treated in accordance with humane endpoints (A humane endpoint can be defined as: “the earliest indicator in an animal experiment of (potential) pain and distress that, within the context of moral justification and scientific endpoints to be met, can be used to avoid or limit the pain and distress by taking actions such as humane killing or terminating, or alleviating the pain and distress” [

8]) to prevent unnecessary suffering. A rat perceived as a pest animal often dies a slow and painful death having ingested the same poison [

6]. This inconsistency generally remains in the background, as pest management is largely outsourced to professionals rendering the used control measures a black box [

6,

7,

9].

In order to facilitate ethical decision-making and include the moral status and welfare of liminal rodents in pest management, various authors have previously indicated animal research ethics as a valuable source. This includes attention for animal welfare (e.g., minimizing suffering), as well as the specific way of justifying actions by means of a decision-making framework [

6,

7,

10,

11,

12]. Whereas in the research context, animals are subjected to a wide range of different procedures that inflict suffering, requiring ethical assessment, in pest management, the focus lies with the method of killing primarily. The welfare implications of pest control methods are usually described by the amount of pain and distress, the duration, the methods for killing, and the effects on animals that either escape from the control or non-target species [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Broom [

4] has classified different control methods by means of their humaneness. Fast-acting killing traps are classified as humane, whereas slow-acting anticoagulants (one of the most used control methods in the Netherlands and most other Western societies) are classified as inhumane [

4,

5] or severe suffering [

12].

1.1. Integrated Pest Management

In the Netherlands, since 2017, the use of anticoagulant rodenticides requires a certification for Integrated Pest Management (IPM) for the control of rats outside buildings [

13]. According to the IPM principles, preventive and non-chemical methods (e.g., mechanical killing traps) should be used before rodenticides [see 6 for a description of IPM]. Preventive methods can consist of cleaning the area, removing food sources, closing buildings, etc. While animal welfare appears a strong argument to consider such a requirement, the primary motivation derives instead from environmental concerns and the increasing resistance in rats against the poison. Nevertheless, the correct application of the IPM principles with a focus on prevention benefits the interests of liminal rodents as well.

1.2. Stakeholder Views

In 2018 the Centre for Sustainable Animal Stewardship (CenSAS) performed a stakeholder consultation regarding the treatment of rats and mice perceived as pests [

14]. Stakeholders (17 persons, all Dutch) represented local and national government(s), animal protection NGOs (Non-governmental organizations), pest controllers, food retail, agricultural sector, or were researchers or advisors in the field of pest control and wildlife management. The consultation highlighted a shared need to take the moral status and welfare of pest rodents more seriously. Everyone supported the need for better application of preventive methods both by professionals and citizens. Control measures should be categorized in terms of suffering, and their usage justified based on clearly stated conditions. Finally, to better implement IPM and responsible rodent management, national coordination, and monitoring under the responsibility of the government is considered crucial.

The outcomes of this earlier study were the start of a multi-stakeholder project, initiated by, and under the lead of CenSAS, for an assessment frame that contributes to more responsible rodent management in which moral status and welfare of rodents are considered. In order to identify relevant moral concerns and dilemmas, as well as to develop an adequate frame that will support ethical decision-making in practice, the knowledge and experience of pest management professionals are indispensable. An online survey among Dutch pest controllers was, therefore, carried out in order to find out more about their attitudes regarding animal welfare in rodent control, their experiences of (moral) dilemmas in practice, and possible ways (among which the use of an assessment frame) to overcome these dilemmas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey

The online survey (details of the survey are available from the corresponding author upon demand) was set up in Dutch using Google Forms. The answers were translated into English for the purpose of this article. The link to the survey, together with the call to take part, was placed on the website of CenSAS and spread via professional associations of pest controllers, newsletters, and websites of stakeholder organizations, personal networks, and social media. No sample size had been predefined since the main function of the survey was to provide a descriptive overview of views and opinions. The survey was open during April and May 2019. The expected time to complete the survey was 15 to 20 min. The results were obtained and processed anonymously. Questions (37 in total) in the survey were of different types using five-point Likert-style questions (never, seldom, sometimes, often, always), 10-response (equally spaced) interval rating scales from 1 (e.g., totally disagree or not important) to 10 (e.g., totally agree or very important), open, multiple-choice, and multiple response questions. A range from 1 to 10 was used for the rating scales since this is a familiar range for Dutch people due to its use for grading at schools. For some questions, respondents had the possibility to provide additional information or add additional answers not provided in the lists. At the beginning of the survey, rats and mice were specified as black and brown rats (Rattus rattus and Rattus norvegicus, respectively) and house mice (Mus musculus).

The survey was divided into six sections. The first section consisted of five statements about the general perception of rats and mice, where respondents could agree with or not on a 1 (totally disagree) to 10 (totally agree) rating scale.

The second section about animal welfare consisted of six questions about the (relative) importance of rodent welfare (Likert scales and 1 to 10 rating scales), conceptions of animal welfare (multiple-response questions), the impact of 10 control methods in terms of animal suffering on a 1 (no welfare impact) to 10 (very large welfare impact) rating scale, and the motivation to improve rodent welfare in pest management on a 1 (I do not want to do more) to 10 (I want to do a lot more) scale. As a further specification, animal interests were defined as ‘living, freedom, and welfare’.

The third section consisted of questions about the type of clients (type of business, sector, etc.), the amount of awareness among clients (Likert scales), and the client’s willingness to invest in preventive methods on a 1 (no willingness) to 10 (much willingness) scale.

The fourth section was to get insight into the attitudes towards existing regulations, IPM, and the belief in prevention. The section consisted of three statements about regulations and IPM. It contained one open question about prevention where respondents were asked to indicate what percentage of nuisance could be solved by preventive methods only according to them.

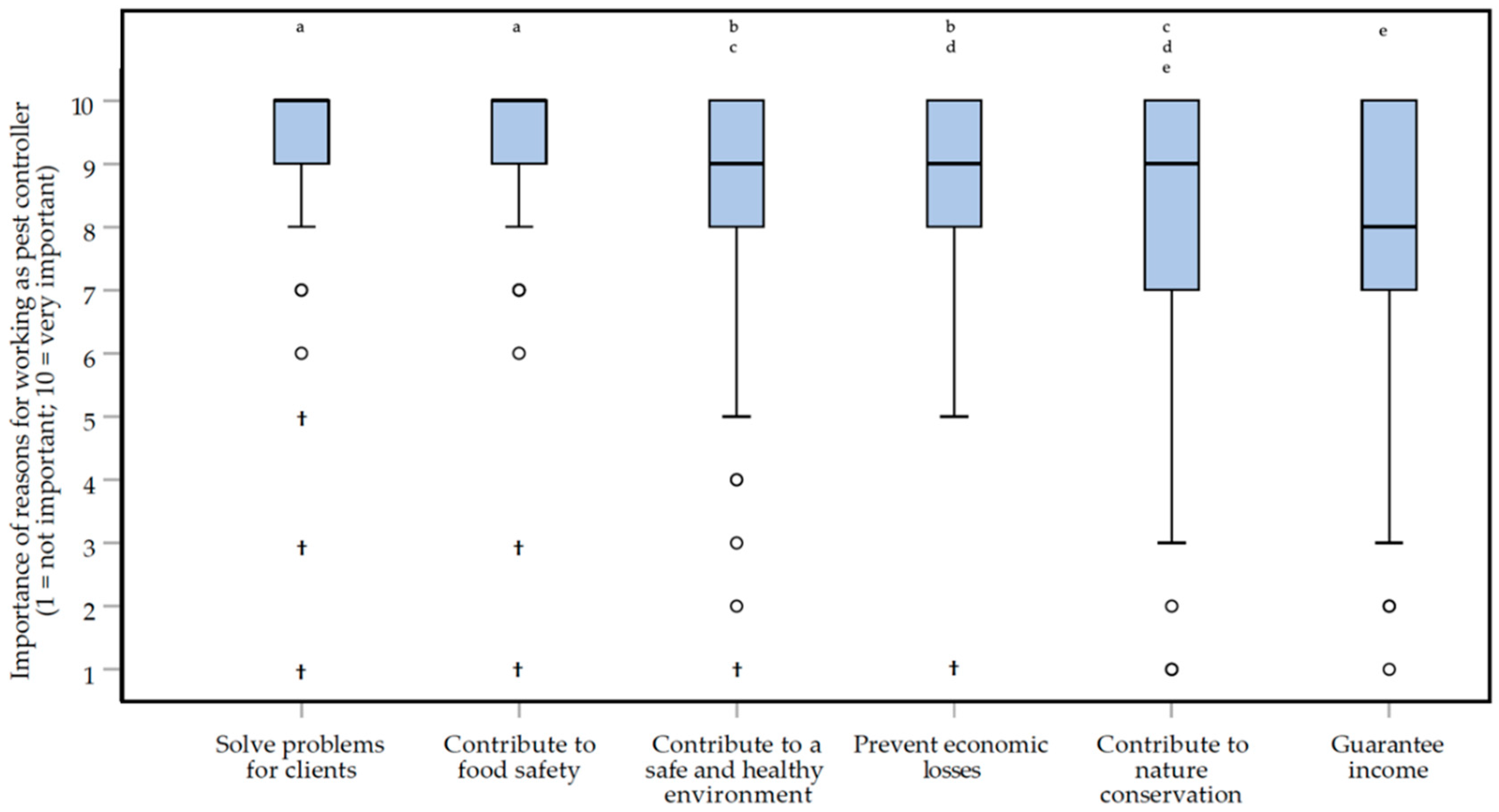

The fifth section about experience and decisions in daily practice consisted of questions about important reasons to work as a pest controller on a 1 (very unimportant) to 10 (very important) rating scale, the weight of (or space for) animal interests in 12 different real life scenarios on a 1 (animal interests do not count) to 10 (animal interests count heavily) scale, the experience of problems or dilemmas (multiple choice and open questions), and the possible solutions for these problems on a 1 (no added value for solving problems) to 10 (large added value for solving problems) scale.

At the end of the survey (sixth section), several demographic data were collected, such as gender, age, membership of a professional association for pest controllers, type of employment, and work region. Furthermore, pest controllers were asked if they had taken any post-graduate course in ethics for pest controllers. Membership of an association for pest controllers could be indicated on four levels: a member of NVPB (Nederlandse Vereniging Plaagdiermanagement Bedrijven), member of PLA..N. (Platform Plaagdierbeheersing Nederland), a member without specification of the association (unspecified member), no member.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Analysis of the survey results was done with the IBM® SPSS® Statistics for Mac (Version 26) computer program (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), using descriptive statistics and inferential statistics for the interval rating data. For this type of data, the Friedman repeated measures test (omnibus) and the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranks test (post-hoc) were used to test for differences between dependent variables (e.g., ‘scored welfare impact of different control methods’ and ‘weight of animal interests in different practical scenarios’). The Kruskal–Wallis test (omnibus) and Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test (post-hoc) were used for testing differences between independent grouping variables (factors). The following grouping variables were tested: (1) with or without post-graduate ethics education, (2) membership of an association for pest controllers, and (3) ownership of companion animals. Descriptive statistics of interval rating data (on a 1 to 10 scale) were provided as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) and displayed in box plots (also known as box-and-whisker plots). Box plots show median values with IQR, highest and lowest non-outlying values (i.e., values up to 1.5 box lengths from the upper or lower edge of the box). In the figures with the box plots (mild) outliers (i.e., cases with values between 1.5 and three box lengths from the upper or lower edge of the box) and extreme cases (i.e., cases with values more than three box lengths from the upper or lower edge of the box) are also indicated.

For the

omnibus and

post-hoc tests Monte Carlo (number of samples was 10,000) and exact

p values (two-tailed) were respectively calculated. To compensate for the increased chance of a type I error as a consequence of multiple hypotheses testing, values of

alpha (

α) were adjusted with the Dunn–Šidák correction. The formula for calculating the

adjusted alpha was:

αadj = 1 − [1 −

α]

1/γ; in which

γ is the number of hypotheses tested (

omnibus tests: ‘number of test variables’ multiplied by ‘the number of

omnibus tests performed’;

post-hoc tests: ‘number of test variables’ multiplied by ‘the number of

omnibus tests performed’ multiplied by ‘the number of pairwise comparisons’) per topic, and

α = 0.05. The adjusted

alpha values for each test used can be found in

Supplementary Table S1. Significant

p values are marked with an asterisk (*) and are reported with six (e.g.,

p = 0.000414*) or seven (

p < 0.0000005*) decimal places, whereas non-significant

p values are reported with two (e.g.,

p = 0.16) to six digits (e.g.,

p = 0.00009) after the decimal point.

Statistical significance represented by

p values may not necessarily confirm practical importance. In our opinion, the size of the observed effects is perhaps more important than statistical significance. Therefore, besides

p values, estimated effect sizes were calculated for both the

omnibus and

post-hoc tests. Effect sizes reported comprise (1) Kendall’s

W value for the Friedman repeated measures test, (2) the eta squared value (

η2) for the Kruskal–Wallis test, and (3) the correlation coefficient

r for the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranks test, and the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test. The formulas [

15] are as follows:

where ‘

n’ is the number of observations (2 × 129 in case of the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranks test),

k is the number of repeated variables per topic,

χ2 is the chi-square statistic for the Friedman repeated measures test,

H is the chi-square statistic for the Kruskal–Wallis test,

g is the number of groups per factor, and

Z is the standardized

z-score of the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranks test or the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test. The thresholds used for qualitative descriptions of the (absolute) values of effect size (i.e.,

W,

η2, or |

r|) are shown in

Table 1. Exact

p values and absolute effect sizes for Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranks test (

post-hoc) could be found in the

Supplementary Tables S2–S9. The exact

p values and absolute effect sizes for the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test (

post-hoc) can be found in the

Supplementary Table S10.

2.3. Ethical Approval

For this type of research, no ethical approval is required in the Netherlands. The design and analysis of the survey are in accordance with the code of conduct of the Association of the Universities in the Netherlands and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) of Utrecht University.

4. Discussion

Attention to moral status and animal welfare in the treatment of liminal rodents perceived as pests seems scarce. At the same time, stakeholders consider this a pressing issue [

14]. The present study is part of an ongoing project to shed light on this area. It does so in the spirit of a bottom-up approach, starting at the grassroots level to uncover relevant considerations and moral issues, generating engagement in the process. For CenSAS, taking the perspective of the animal is key. The shared commitment among stakeholders to take the interests of animals seriously in pest management strategies provides an important condition to participate and facilitate this process. Beyond promoting collaboration between stakeholders and managing the project, CenSAS contributes by means of expertise regarding animals and their interests, including both animal welfare science and philosophy (ethics in particular). The goal of the project is to develop an assessment frame for responsible pest management, which can be used by the professionals in practice. In light of the bottom-up approach, the input of pest controllers is indispensable. Therefore, an online survey among Dutch pest controllers was carried out to learn more about their attitudes regarding animal welfare in rodent control, their experiences of (moral) dilemmas in practice, and possible ways (among which the use of an assessment frame) to overcome these dilemmas.

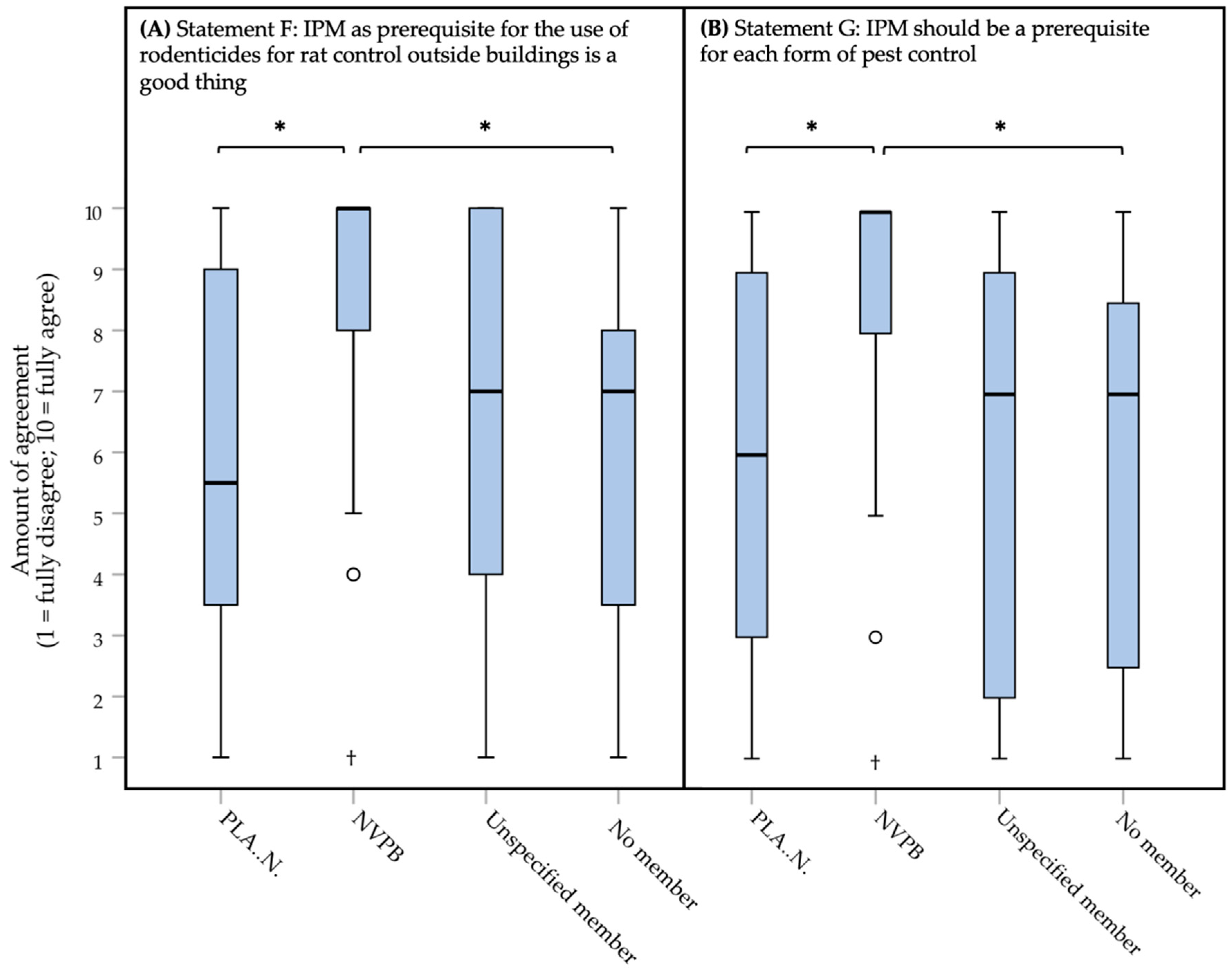

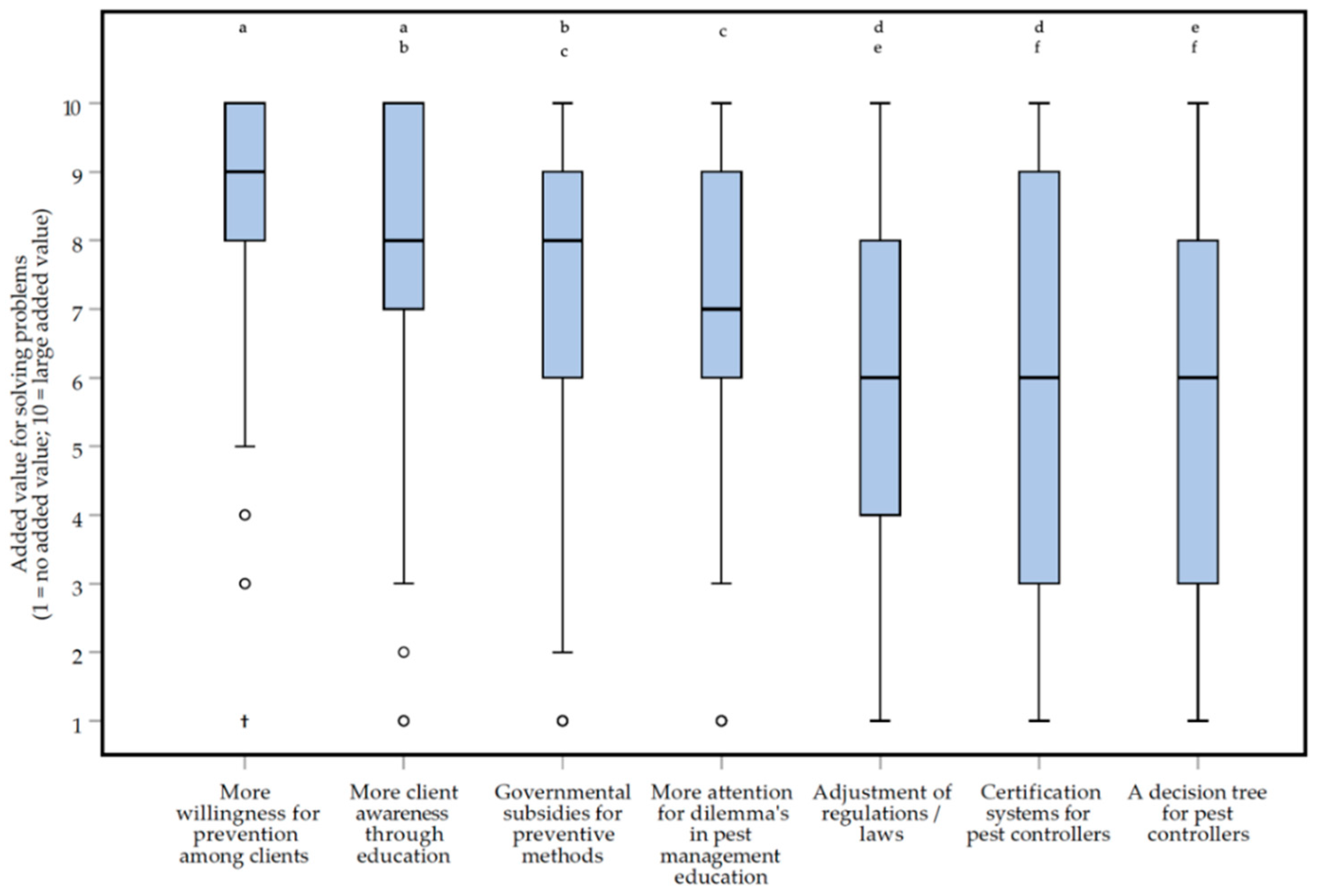

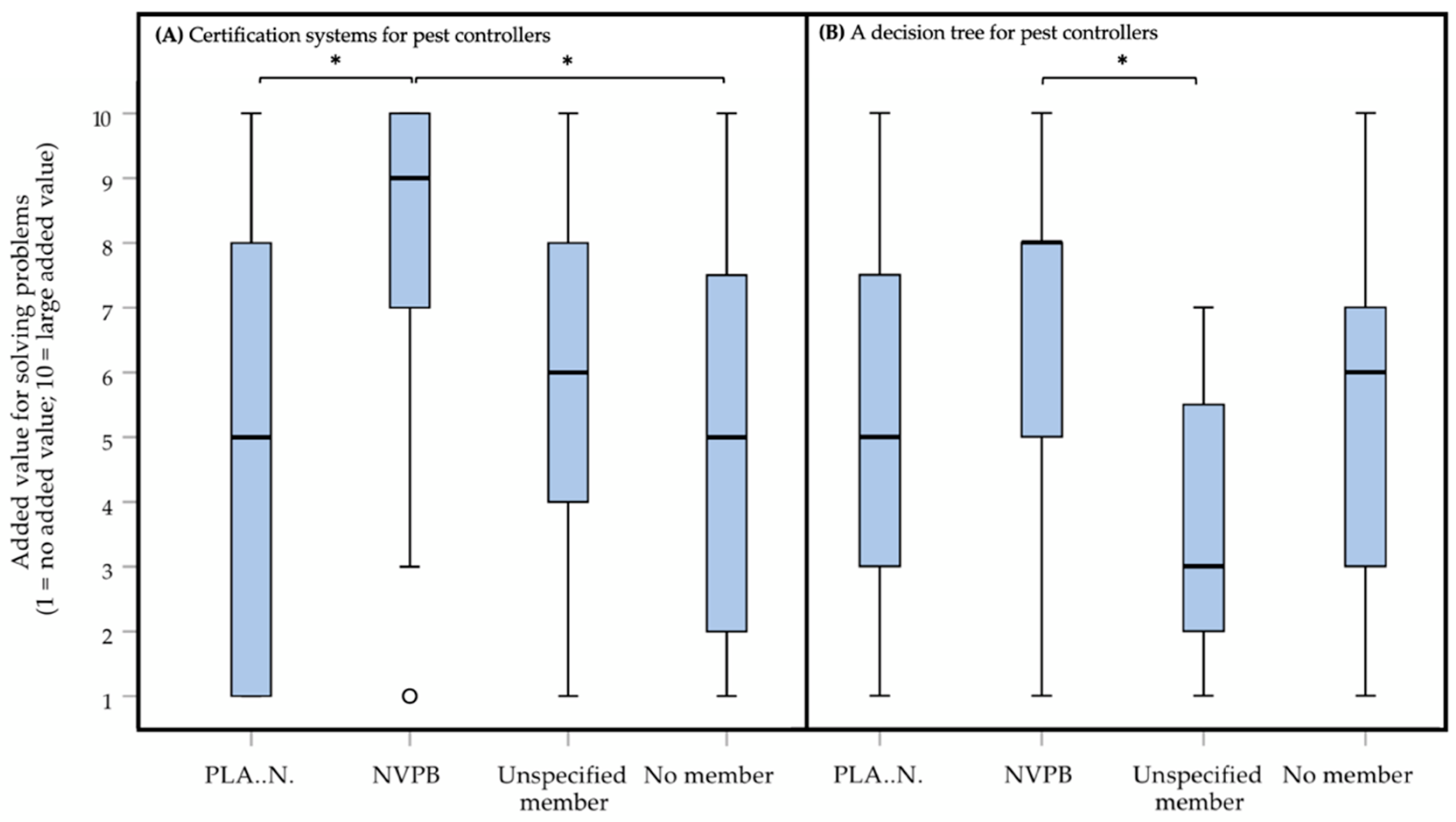

The respondents of the survey believe that rats and mice have interests (e.g., living, freedom, welfare), and they are, in general, quite positive about IPM and the effects preventive methods can have (

Figure 1). These findings are relevant if one wants to develop an assessment frame that starts with prevention, and which has to weigh potential harm to the interests of animals against the interests of humans. The results show that respondents being a member of the NVPB were more positive about IPM than other respondents, except for unspecified members (

Figure 2). At the moment, we are unable to fully explain this finding. They may be more positive about regulations and guidance for good practices in general, since these respondents also tended to be more positive about ‘

Adjustments of regulations’, ‘

Certification systems’, and ‘

A decision tree’ as solutions for overcoming problems in practice. All respondents agreed with the statement that only certified pest controllers should be allowed to manage pests. This may indicate that they view their job as a profession that should be acknowledged as such.

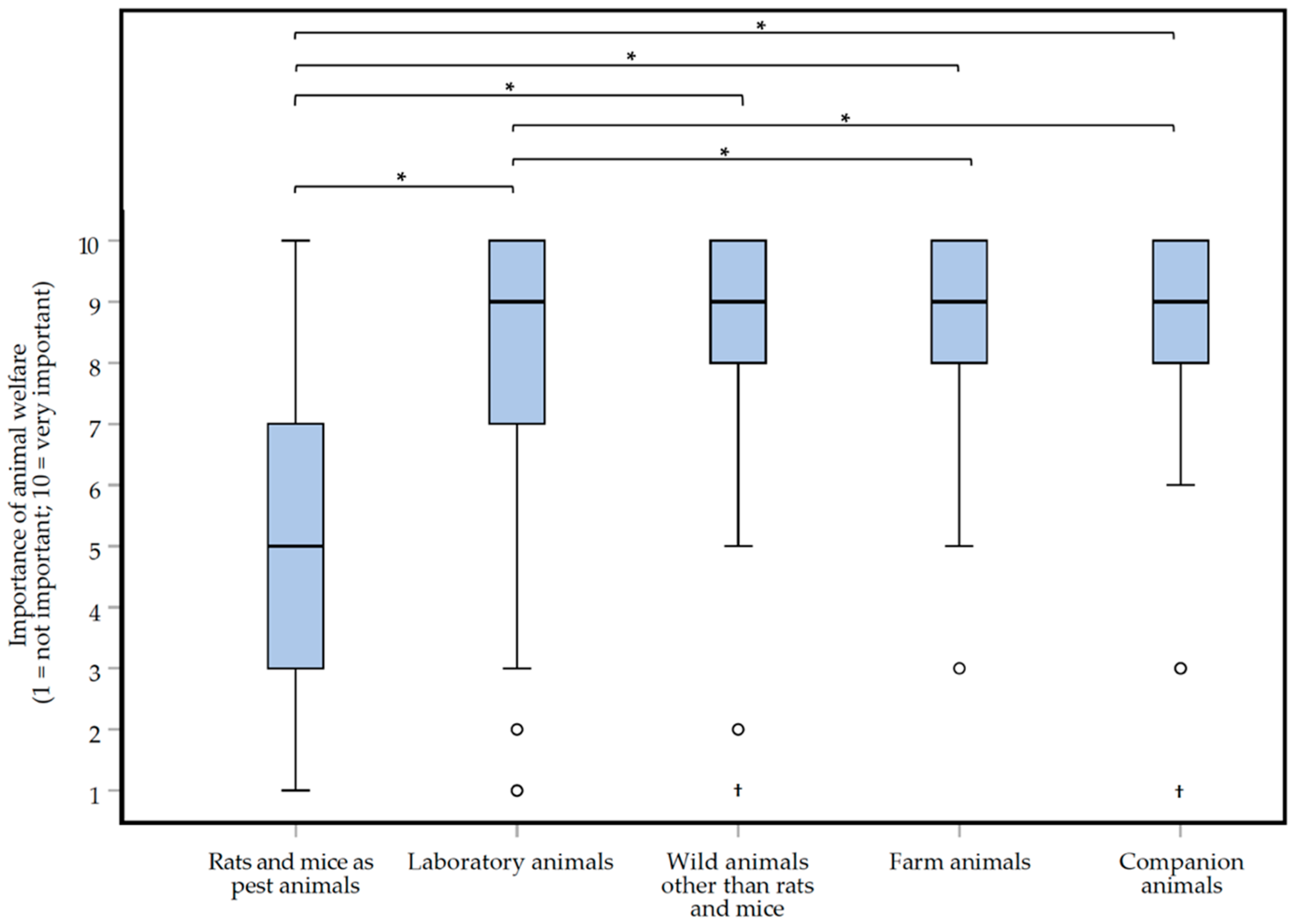

The results show that the respondents do consider animal welfare during their job (

Figure 3B). The differences found in the scoring of the importance of animal welfare (

Figure 4), supports earlier findings of a variety or even inconsistencies in the treatment of animals, depending on the context [

18]. What precisely causes these differences to arise remains somewhat unclear. Likely various aspects, such as a difference in the (moral) evaluation of liminal rodents in comparison to other animals [

1], the plurality of views on the moral status of animals [

19], the difference due to ethical choices in the weighing between animal welfare and human interests, and the importance of moral intuitions [

20], including the ‘yuck factor’ [

21] play a role.

Surprisingly, no statistically significant differences were found for the grouping variable ‘ethics course’. This was unexpected, since one may assume to find that respondents who took a post-graduate ethics course (with a focus on animal welfare and weighing animal against human interests) would have a different attitude towards the treatment and welfare of rats and mice, especially when it comes to the weighing of animal interests against human interests. At the moment, we are unable to explain this finding. Focus group dialogues should shed more light on both this finding and the differences found in the importance of welfare depending on the animal category.

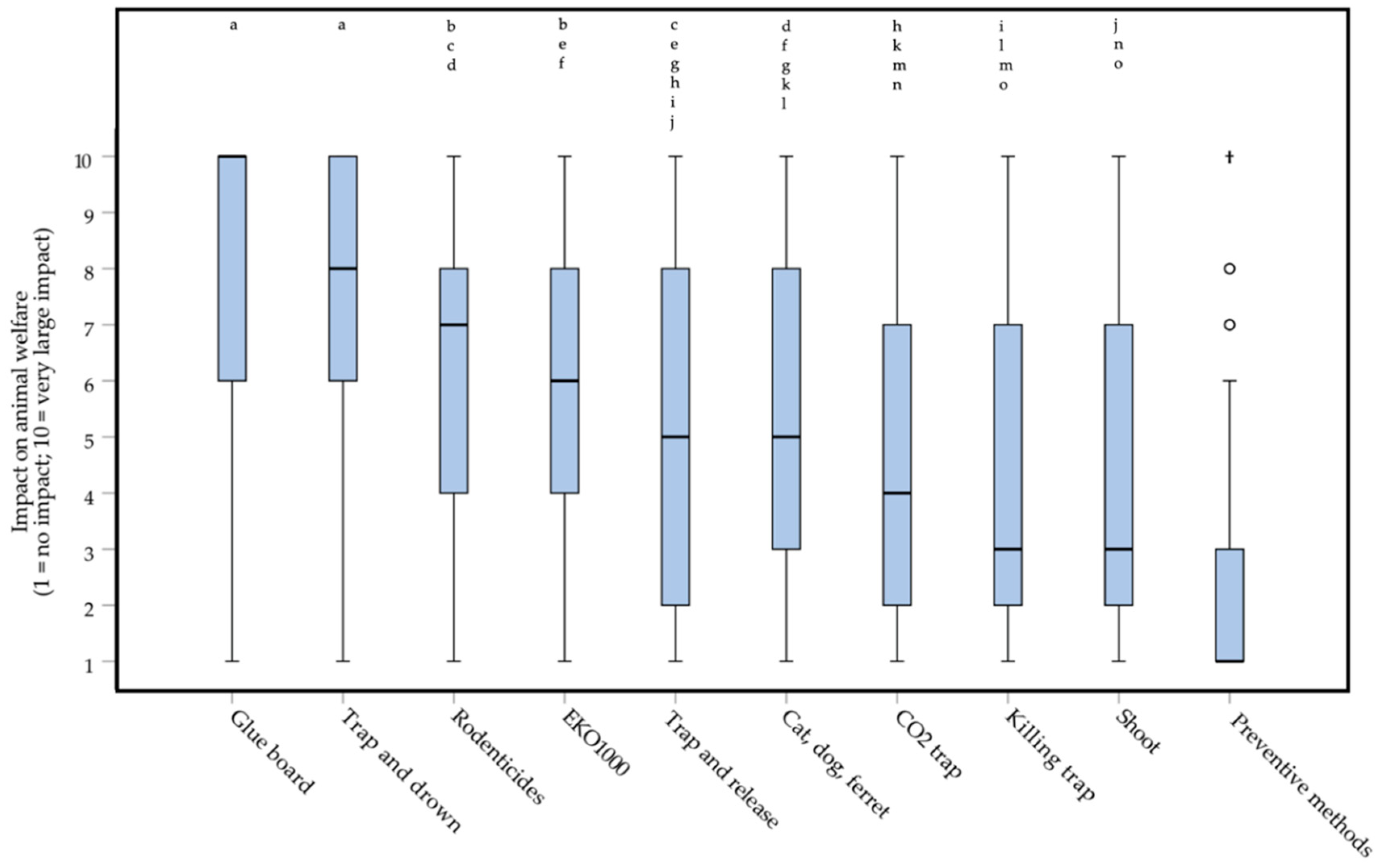

The great majority of respondents indicated using rodenticides. At the same time, they score this method as one with a high impact on welfare (

Figure 5). This finding may indicate the existence of a ‘rodenticide dilemma’ and may point at a need for new control methods, which are both effective and less harmful to the animals involved. It might be useful to discuss and investigate this further to see if pest controllers do indeed experience this as a dilemma or not. Also, it should be discussed if methods with the highest welfare impact (glue trap, drowning) should be used at all. The welfare impact scores are given by pest controllers. It tells us how they think about different methods, but it does not tell the real welfare impact. Scoring based on scientific knowledge and expertise in this particular field is necessary to rate the impact of methods in an objective way. The model developed by Sharp and Saunders [

22] could be a useful tool to do so. This model constitutes two parts, one part looks at the impact of control methods based on overall welfare and the duration of the impact. The other part looks at the effects of a killing method by looking at the intensity and duration of suffering caused. With this model, the welfare impact can be analyzed thoroughly.

Animal welfare comprises an important building block for the assessment framework. Just as various conceptions of animal welfare exist in the literature, e.g., [

23,

24], a broad and diverse range also existed among stakeholders [

14]. How should we deal with a plurality of views regarding the meaning of such a crucial concept? We have distinguished between suffering as a measure of animal welfare to assess the impact of pest management methodologies, and animal interests as an open-ended value for the participant to consider in brief examples of cases. In addition, we ask the participants to indicate what best approximates animal welfare out of the following features—the absence of suffering, health, natural behavior, feeling good, and control regarding one’s life (

Figure 3A). Natural behavior turned out to be the most important aspect of welfare for the respondents. Animal welfare as a concept in the management of liminal rodents will be explored further elsewhere as part of the ongoing project.

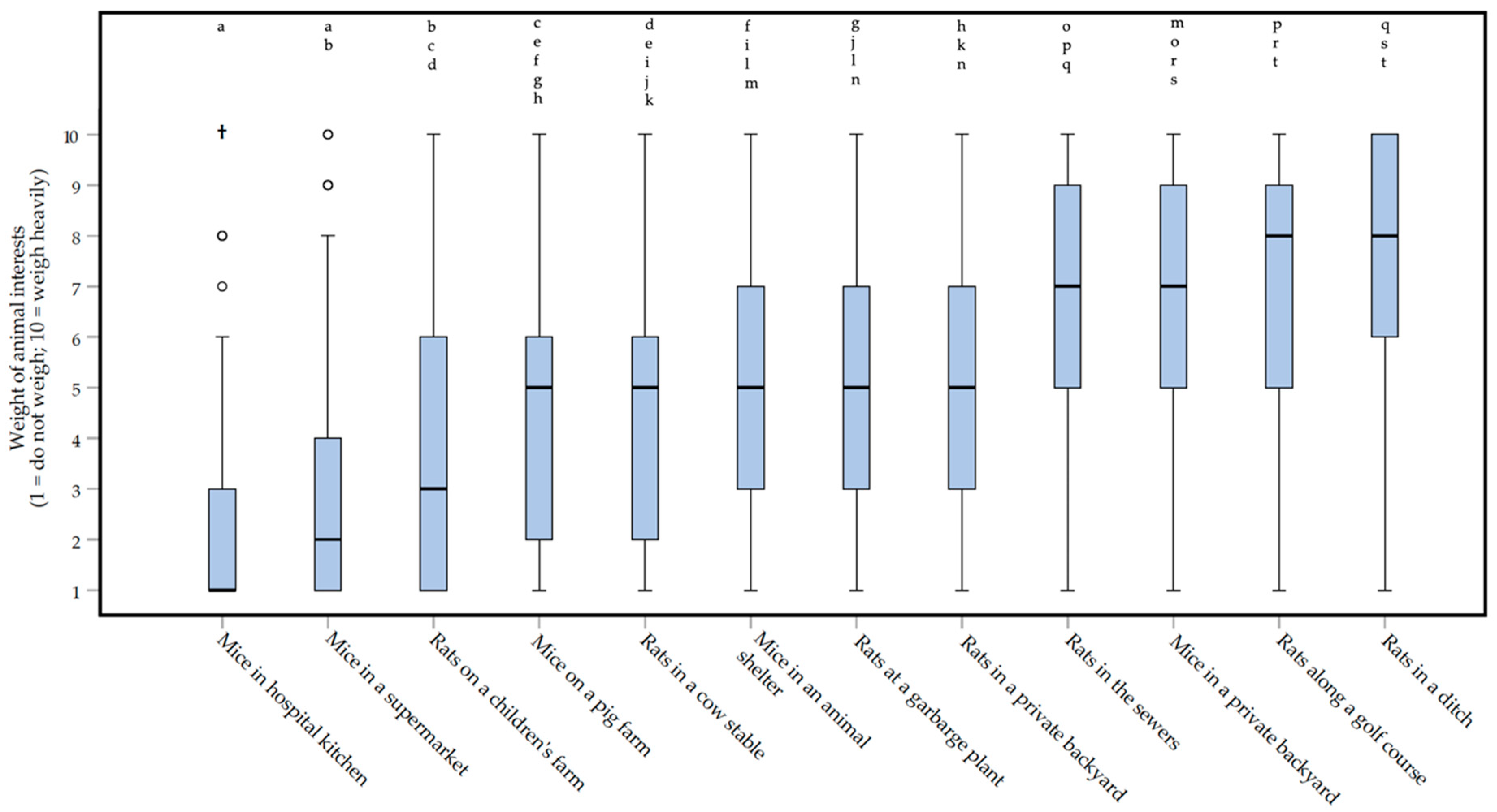

As for the welfare impact scores of control methods, the scores for weighing animal interests show some grey areas (

Figure 6). Together, these findings offer the potential for in-depth discussions within the focus groups. Furthermore, the combination of welfare impact scores and animal interest scores could be used to develop an assessment frame to facilitate responsible rodent management. On the one hand, these findings suggest there may be practical situations in which the animal interests are deemed less important, even to the extent of considering more harmful control methods. On the other hand, there are situations in which animal interests are explicitly taken into account, and only less harmful or even no control methods are deemed acceptable. Besides the differences between scenarios, respondents see differences between rats and mice. Whether one frame for both species will do, therefore, remains unclear. Maybe there should be separate frames for different species, or perhaps the frame should question the moral relevance of species.

Respondents indicated encountering problems in practice and they attributed these problems to clients. At the same time, they deemed client satisfaction important for work motivation (

Figure 10). The combination of these findings may point at another dilemma. On the one hand, the pest controllers want to assure client satisfaction, while on the other hand, they sometimes need to be critical of client behaviors and attitudes. This calls for strong communicative skills as indispensable for pest management professionals, both in terms of fostering ecological as well as moral awareness in clients. In order to promote investment in preventive methods, pest management professionals have to be able to educate clients on the ecological drivers of the existing conflict with liminal rodents. In moral terms, pest management professionals have to engage clients in ethical decision making and diminish strong biases in this process [

25]. It is worth exploring whether the assessment-frame as a communication tool can facilitate pest management in these capacities and support them in the dilemmas they face.

The initial idea of the ongoing project was to develop an assessment frame (in the survey the Dutch word ‘

Beslisboom’, meaning decision tree, was used) for pest controllers specifically. Noteworthy, a decision tree for pest controllers as a possible solution for problems in practice (

Figure 8), together with the adjustment of regulations and certification systems for pest controllers, scored the lowest (medians of 6), and scored significantly lower than the other solutions provided (

p-values < 0.0000005, and absolute effect sizes |

r|, ranging from 0.1 to 0.5). Taking this into account, in addition to the findings of client awareness, an assessment frame that could be used by both pest controllers and their clients together may be more helpful to overcome the identified problems. Besides ethical decision-making, such a frame may function as a communication tool and improve the controller-client relationship. We will look into this further in focus groups and the continuation of our research. Variation between pest controllers may exist, since respondents being a member of NVPB were more positive about ‘

A decision tree for pest controllers’ as a solution for problems in practice than respondents being an unspecified member (

Figure 9).

One perhaps wonders how the assessment frame relates to earlier suggestions to extrapolate ethical assessment frameworks from animal research ethics to the context of pest management [

6]. First of all, (1) our objective is to integrate concern for animals at the level of practice, bottom-up, whereas these ethical assessment methods indicated in the literature—which could prove valuable in managing conflicts between humans and liminal rodents—are extrapolated from another field, to be introduced top-down. Authorities could for example follow up on the suggestions made in the literature and require that all pest management measures require the application of the three Rs and a harm-benefit analysis. We have seen, however, that these kinds of solutions may not prove very beneficial in the eyes of the respondents, and there are further methodological questions to be addressed as well [

26]. Our bottom-up approach starts off from the concerns raised by professionals themselves. Taken together with the shared commitment among stakeholders to work towards responsible pest management, our approach not only generates a support base but also promotes moral awareness by inviting professionals to reflect on the questions raised in the survey. As such, the resulting assessment frame on this approach will reflect and build upon moral engagement within the profession itself.

As a second point (2), we need to establish whether these tools are adequate in themselves. To what extent should we take these methods at face value, ready for extrapolation? What exactly happens when animal research is justified by means of a harm-benefit analysis? To what extent does one’s perception (including emotional engagement) of the animals in question introduce bias, either explicitly or implicitly, in ethical assessment? We explore these questions more in-depth elsewhere [

25].

As a third point (3), if prevention becomes an important part of management strategies, the interaction between humans and liminal rodents appears to move more towards co-existence rather than mere conflict. Such a shift in perspective will likely require new sources, novel “tools” to think about living together with animals. This could prove a next step in the development from “pest eradication” to “pest management”, perhaps resulting in consultancy, primarily aimed at mediating the interests of both humans and liminal rodents [

25].

As a final point (4), we are interested in the professional agency of individual pest management professionals. This is why the current survey, as we hypothesize, needs to be deepened by focus groups, as well as put into the context of determinants that shape the range of professional agency of pest management professionals. How does professional training shape their capabilities to negotiate the demands of clients, employers, society, and the liminal rodents [

27]? To what extent should we expect change to arise from individual professionals, supported by an assessment frame, rather than as a result of more general regulations and restrictions? In order to develop frameworks that truly support the decision-making of individual professionals, unravelling the underlying drivers that shape current pest management strategies emerges as the anticipated next step.