Establishing Animal Welfare Rules of Conduct for the Portuguese Veterinary Profession—Results from a Policy Delphi with Vignettes

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

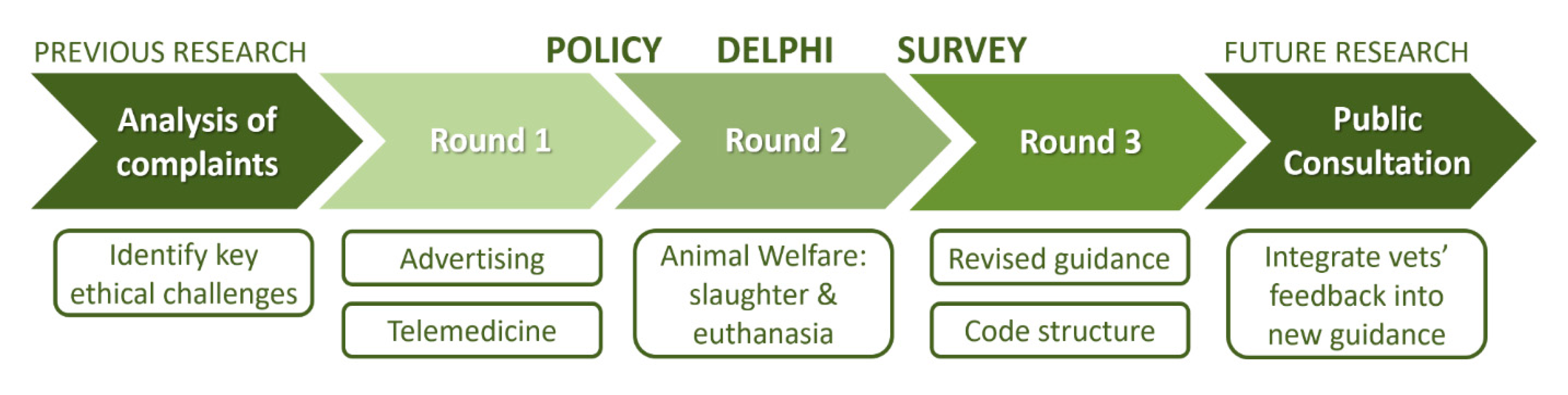

2. Materials and Methods

- Veterinarians registered with the OMV and working in Portugal;

- No previous sanctions within the last five years or outstanding fees;

- Policy-making experience with Portuguese veterinary organisations;

- Gender balance;

- Proportionality in terms of age groups;

- Broad geographical distribution in terms of working location;

- Broad professional experience and field of work;

- Diverse educational backgrounds.

3. Results

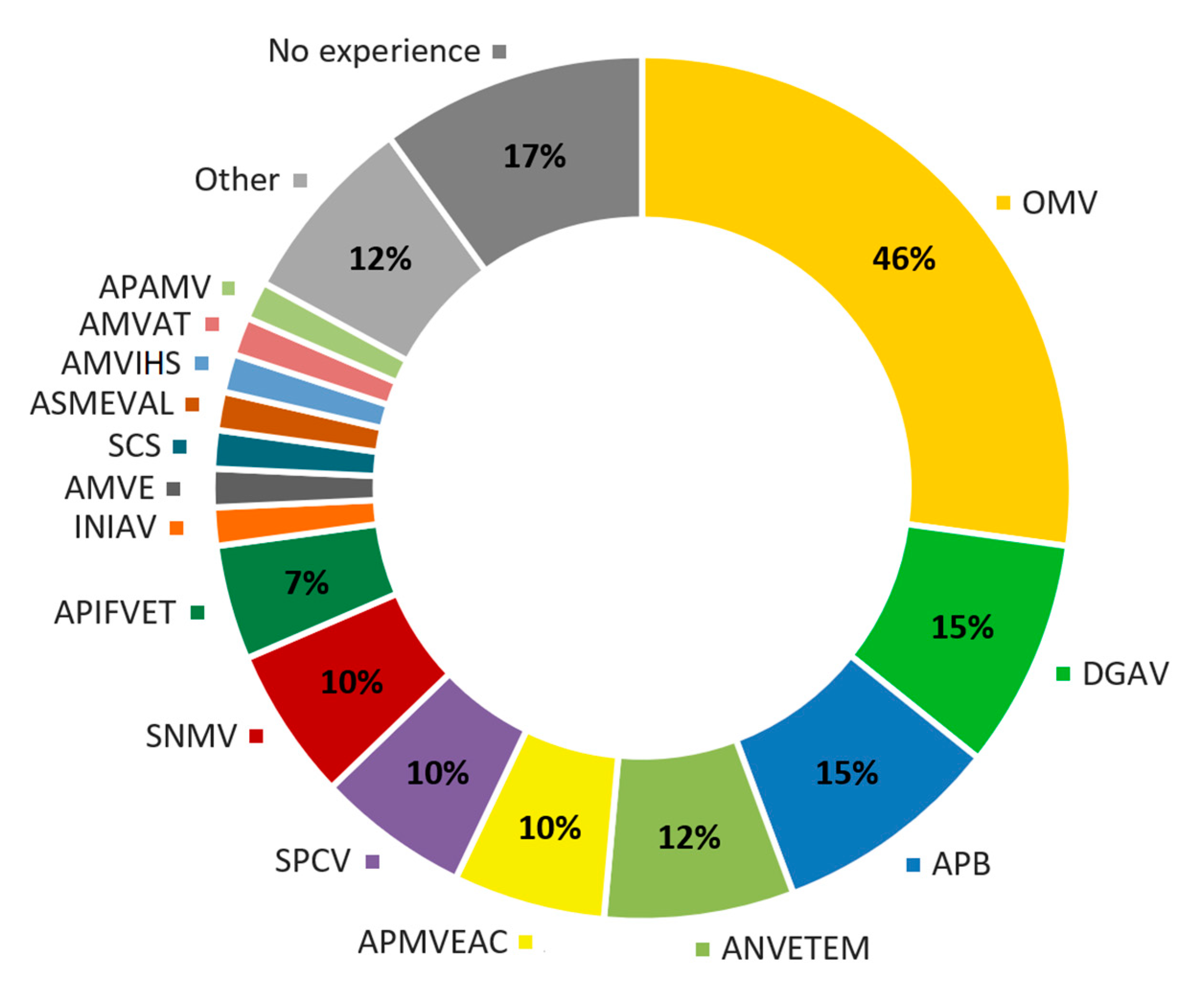

3.1. Demographics

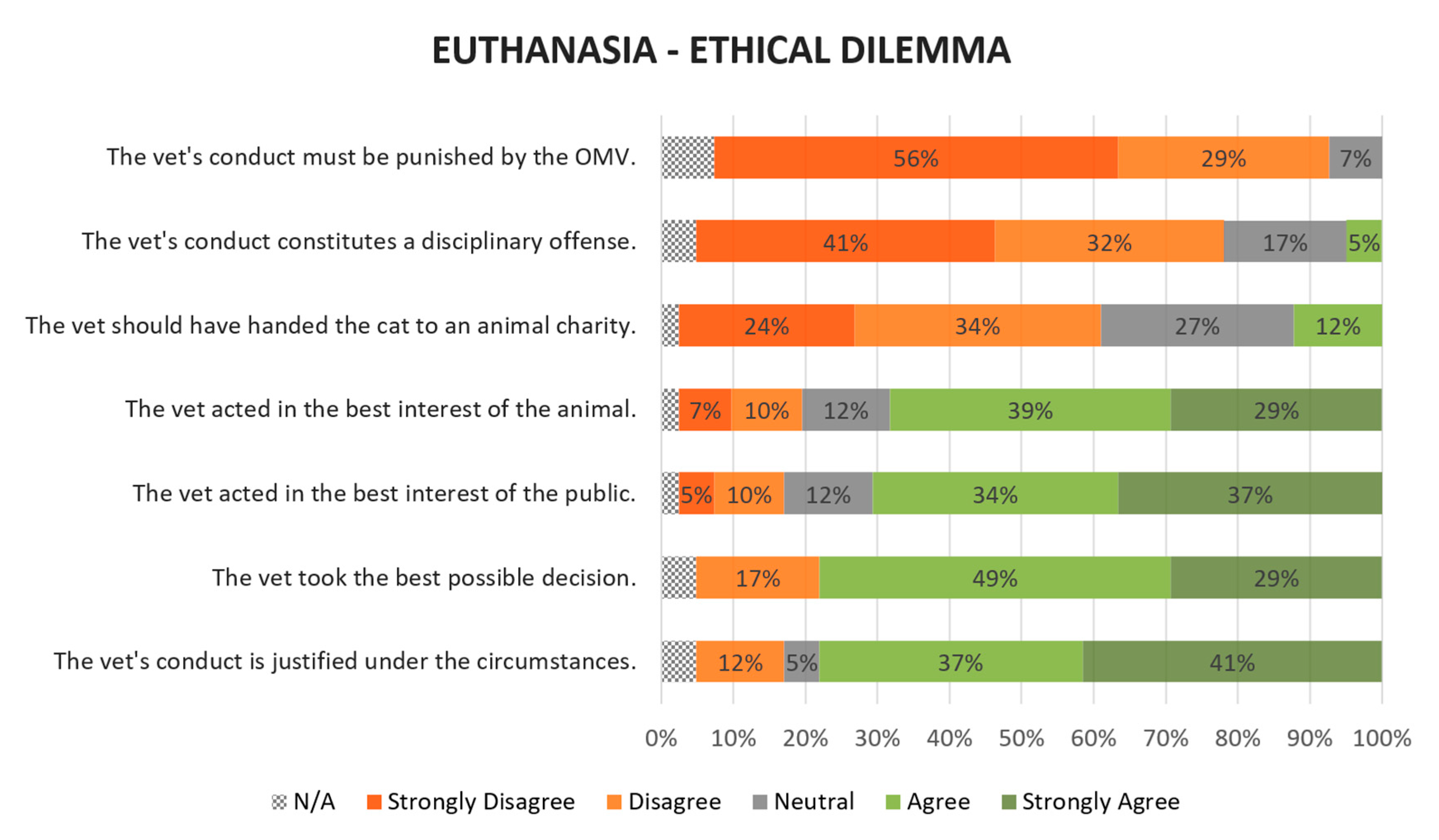

3.2. Vignette: Euthanasia

3.3. Vignette: Transport and On-Farm Slaughter

“Unfortunately, we are often forced to deal with this dilemma (…) objectively, slaughter outside the slaughterhouse [on-farm emergency slaughter] is not an option. There are often no means available and when they do exist, it takes much longer than having the cow slaughtered at the slaughterhouse. That is, if we defend on-farm slaughter, (...) welfare is not improved since the animal is often subjected to many more hours/days of suffering”.

There should be an interconnection of services, namely between assistant veterinarians, local veterinary officers and DGAV officials, to gather the necessary equipment that would allow direct collaboration to resolve cases of slaughter outside the slaughterhouse.

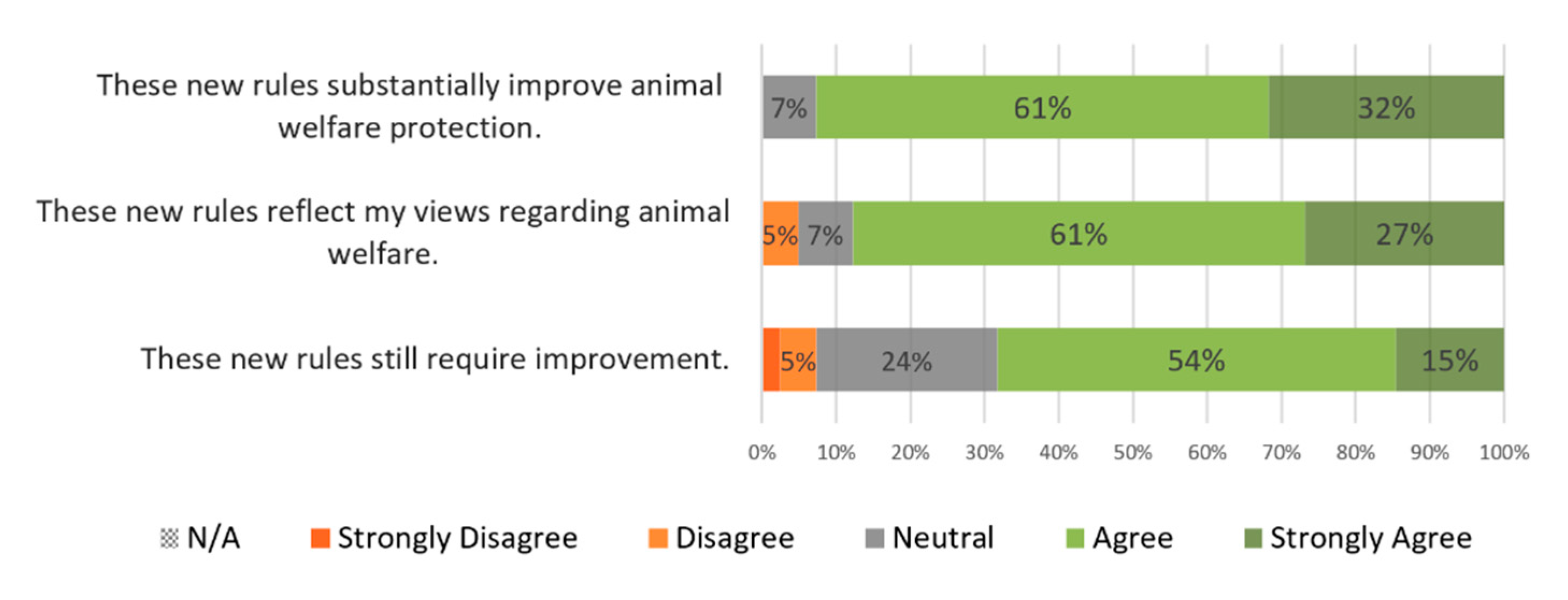

3.4. Revised Guidance

- Veterinarians must be respectful of animals, avoiding violence and unnecessary suffering in their handing, restraint, treatment or transport.

- Veterinarians must be aware of animal health and welfare legislation.

- Veterinarians must report to the competent authorities cases that may result in unjustified suffering, abandonment or death (safeguarding professional secrecy, where applicable).

- Veterinarians must provide first aid to animals, according to their competence.

- Likewise, it is the duty of any veterinarian to ensure that animals in irretrievable suffering are euthanased or slaughtered as soon as possible and using methods deemed fit for purpose.

- Only veterinarians may decide and practice animal euthanasia.

- The decision to euthanize an animal shall consider, in addition to animal health and welfare, public health as well as the legitimate interests of its owner or keeper.

- The preceding points do not exclude the delegation of veterinary acts in urgent cases, epidemics or disasters.

- The veterinarian is required to obtain consent from the rightful owner or keeper of the animal prior to any treatment or euthanasia.

- The cases described in points 4 and 5 do not require consent, although it should be sought prior to practice.

4. Discussion

Veterinarians have to operate in a force-field of various responsibilities, obligations, demands and expectations, of which One Health appears only to make more complicated. However, letting complexity and conflicting demands narrow and blunt moral agency should be prevented if only to protect the wellbeing of veterinarians themselves[33].

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

A.1. Euthanasia

A.2. Emergency Slaughter

References

- De Briyne, N.; Vidović, J.; Morton, D.B.; Magalhães-Sant’Ana, M. Evolution of the teaching of animal welfare science, ethics and law in European veterinary schools (2012–2019). Animals 2020, 10, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães-Sant’Ana, M.; More, S.J.; Morton, D.B.; Osborne, M.; Hanlon, A. What do European veterinary codes of conduct actually say and mean? A case study approach. Vet. Rec. 2015, 176, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stassen, E.N.; Meijboom, F.L.B. The End of Animal Life: A Start for Ethical Debate; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2016; ISBN 978-90-8686-260-3. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, C.A.; McDonald, M. Ethical dilemmas in veterinary medicine. Vet. Clin. Small Anim. Pract. 2007, 37, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, N.H.; Magalhães-Sant’Ana, M.; Olsson, I.A.S. Welfare and quantity of life. In Dilemmas in Animal Welfare; Appleby, M.C., Weary, D.M., Sandøe, P., Eds.; CABI: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-78064-216-1. [Google Scholar]

- Lei n.o 27/2016, Aprova Medidas Para a Criação de uma Rede de Centros de Recolha Oficial de Animais e Estabelece a Proibição do Abate de Animais Errantes Como Forma de Controlo da População, Diário Da República n.o 161/2016, Série I de 2016-08-23. pp. 2827–2828. Available online: https://data.dre.pt/eli/lei/27/2016/08/23/p/dre/pt/html (accessed on 14 August 2020). (In Portuguese).

- Dürnberger, C. It’s Not about Ethical Dilemmas: A survey of Bavarian veterinary officers’ opinions on moral challenges and an e-learning ethics course. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2019, 32, 891–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, P.; McKevitt, A. Analysis of the operation of on farm emergency slaughter of bovine animals in the Republic of Ireland. Ir. Vet. J. 2016, 69, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullinane, M.; O’Sullivan, E.; Collins, G.; Collins, D.; More, S. Veterinary certificates for emergency or casualty slaughter bovine animals in the Republic of Ireland: Are the welfare needs of certified animals adequately protected? Anim. Welf. 2012, 21, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães-Sant’Ana, M.; More, S.J.; Morton, D.B.; Hanlon, A.J. Challenges facing the veterinary profession in Ireland: 3. emergency and casualty slaughter certification. Ir. Vet. J. 2017, 70, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HAS. On-Farm Slaughter of Livestock for Consumption; Humane Slaughter Association: Wheathampstead, UK, 2018; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães-Sant’Ana, M.; Whiting, M.; Stilwell, G.; Peleteiro, M.C. What challenges is the veterinary profession facing? An analysis of complaints against veterinarians in Portugal. In Professionals in Food Chains—Ethics, Roles and Responsibilities; Springer, S., Grimm, H., Eds.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 302–307. ISBN 978-90-8686-321-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, E.; Fawcett, A.; Brouwer, E.; Rau, J.; Turner, P.V. Speaking Up: Veterinary Ethical Responsibilities and Animal Welfare Issues in Everyday Practice. Animals 2018, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Council. Council Regulation (EC) No1/2005 of 22 December 2004 on the Protection of Animals during Transport and Related Operations and Amending Directives 64/432/EEC and 93/119/EC and Regulation (EC) No 1255/97. 2004. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32005R0001 (accessed on 14 August 2020).

- DGAV. Aptidão Para o Transporte e Abate de Emergência—Guia de Boas Práticas; Direção Geral de Alimentação e Veterinária: Lisboa, Portugal, 2012. (In Portuguese)

- Magalhães-Sant’Ana, M.; More, S.J.; Morton, D.B.; Hanlon, A. Ethical challenges facing veterinary professionals in Ireland: Results from Policy Delphi with vignette methodology. Vet. Rec. 2016, 179, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, J.; Hanlon, A.; More, S.J.; Wall, P.G.; Duggan, V. Policy Delphi with vignette methodology as a tool to evaluate the perception of equine welfare. Vet. J. 2009, 181, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, J. The vignette technique in survey research. Sociology 1987, 21, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meskell, P.; Murphy, K.; Shaw, D.G.; Casey, D. Insights into the use and complexities of the Policy Delphi technique. Nurse Res. 2014, 21, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães-Sant’Ana, M.M.; Peleteiro, M.C.; Stilwell, G. Opinions of Portuguese veterinarians on telemedicine—A policy Delphi study. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landeta, J. Current validity of the Delphi method in social sciences. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2006, 73, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainwright, P.; Gallagher, A.; Tompsett, H.; Atkins, C. The use of vignettes within a Delphi exercise: A useful approach in empirical ethics? J. Med. Ethics 2010, 36, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magalhães-Sant’Ana, M.; Hanlon, A.J. Straight from the horse’s mouth: Using vignettes to support student learning in veterinary ethics. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2016, 43, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portaria 146/2017, Regulamenta a Criação De Uma Rede Efetiva De Centros De Recolha Oficial De Animais De Companhia, Fixa As Normas Que Regulam O Destino Dos Animais Acolhidos Nestes Centros E Estabelece As Normas Para o Controlo De Animais Errantes. Diário Da República n.o 81/2017, Série I de 2017-04-26. Available online: https://dre.pt/home/-/dre/106926976/details (accessed on 14 August 2020). (In Portuguese).

- Despacho 6928/2020—Determina a Constituição de Um Grupo de Trabalho Designado «Grupo Trabalho Para o Bem-estar Animal». Diário da República n.o 129/2020, Série II de 2020-07-06. Available online: https://dre.pt/home/-/dre/137247708/details (accessed on 14 August 2020). (In Portuguese).

- Dürnberger, C.; Weich, K. Conflicting norms as the rule and not the exception—Ethics for veterinary officers. In Food Futures: Ethics, Science and Culture; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 285–290. ISBN 978-90-8686-288-7. [Google Scholar]

- Italian Government Legge 14 Agosto 1991, n. 281. Legge Quadro in Materia di Animali D’affezione e Prevenzione del Randagismo. Gazzetta Ufficiale Della Repubblica Italiana n. 203, 30 Agosto 1991. 1991. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=1991-08-30&atto.codiceRedazionale=091G0324 (accessed on 14 August 2020). (In Italian).

- Thodberg, K.; Gould, L.M.; Støier, S.; Anneberg, I.; Thomsen, P.T.; Herskin, M.S. Experiences and opinions of Danish livestock drivers transporting sows regarding fitness for transport and management choices relevant for animal welfare. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koralesky, K.E.; Fraser, D. Perceptions of on-farm emergency slaughter for dairy cows in British Columbia. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Animals’ Angels. The Myth of Enforcement of Regulation (EC) No 1/2005 on the Protection of Animals during Transport; Animals’ Angels Press: Frankfurt, Germany, 2016; p. 200. [Google Scholar]

- Yeates, J.; McKeegan, D. Ten steps for resolving ethical dilemmas in veterinary practice. Inpractice 2019, 41, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwland, J.; Meijboom, F.L.B. One health: How interdependence enriches veterinary ethics education. Animals 2020, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montoya, A.I.A.; Hazel, S.; Matthew, S.M.; McArthur, M.L. Moral distress in veterinarians. Vet. Rec. 2019, 185, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moses, L.; Malowney, M.J.; Boyd, J.W. Ethical conflict and moral distress in veterinary practice: A survey of North American veterinarians. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2018, 32, 2115–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Topic | Vignette | Legal Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Euthanasia (animal shelter) | Marta is a local authority vet at an urban municipality in the north of Portugal. A cat that suffered a road traffic accident arrives at the animal shelter. The cat, feral and difficult to handle, has tail fractures and lacerations that require surgery. It also presents generalized dermatophytosis (ringworm). Marta assesses the case and decides to euthanase the cat. However, Marta fears that she may incur in serious disciplinary offense because it can be argued that the case falls outside the exceptions provided by the law. | Law no. 27/2016—Restricts the euthanasia of animals to “cases of proven incurable disease and when it proves to be the only means to eliminate irretrievable pain and suffering”. |

| Fitness for transport and on-farm slaughter | Pedro is an assistant veterinarian at a dairy farm in the district of Évora. He was called because of a downer cow, that the farmer wants to cull. In the absence of adequate means to perform on-farm emergency slaughter, Pedro opts for casualty slaughter at the slaughterhouse. The vehicle is prepared with a litter, the cow is hoisted in order to avoid trauma as much as possible, and transported to the nearest slaughterhouse (45 min drive). “It’s the best for everyone,” says Pedro. “Within an hour the animal will be slaughtered and the carcass can be salvaged. Euthanizing the animal on farm would do nothing to solve the problem and would have caused unnecessary loss”. | European Council Regulation (EC) no. 1/2005—Animals that are unable to move independently without pain or to walk unassisted shall not be considered fit for transport. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Magalhães-Sant'Ana, M.; Peleteiro, M.C.; Stilwell, G. Establishing Animal Welfare Rules of Conduct for the Portuguese Veterinary Profession—Results from a Policy Delphi with Vignettes. Animals 2020, 10, 1596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10091596

Magalhães-Sant'Ana M, Peleteiro MC, Stilwell G. Establishing Animal Welfare Rules of Conduct for the Portuguese Veterinary Profession—Results from a Policy Delphi with Vignettes. Animals. 2020; 10(9):1596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10091596

Chicago/Turabian StyleMagalhães-Sant'Ana, Manuel, Maria Conceição Peleteiro, and George Stilwell. 2020. "Establishing Animal Welfare Rules of Conduct for the Portuguese Veterinary Profession—Results from a Policy Delphi with Vignettes" Animals 10, no. 9: 1596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10091596

APA StyleMagalhães-Sant'Ana, M., Peleteiro, M. C., & Stilwell, G. (2020). Establishing Animal Welfare Rules of Conduct for the Portuguese Veterinary Profession—Results from a Policy Delphi with Vignettes. Animals, 10(9), 1596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10091596