Domestic Foal Weaning: Need for Re-Thinking Breeding Practices?

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Spontaneous Weaning In (Semi-) Natural Conditions: An Overview of The Scientific Literature

2.1. Social Structure, Reproduction and Gestation

2.2. Dynamics of the Mare–foal Relationship and Weaning Process

2.2.1. Dietary Independency: A Gradual Transition from a Milk Diet to Solid Food

2.2.2. Social Emancipation: A Progressive Widening of the Social Network

2.2.3. Conclusion

2.3. Natural Foal Weaning and Factors of Variation

2.3.1. Age at Weaning

2.3.2. Factors of Variation

- The reproductive status of the mare (i.e., pregnant or non-pregnant mare) has been considered an important factor determining the time of weaning [37,38]. Pregnant mares tend to wean their foals on average 3-4 months before giving birth to the next foal, at the time of gestation when the energy costs become significant: indeed, the fetal growth, which is at first slow, increases exponentially during the last trimester of pregnancy and the nutrient requirements of the fetus become significantly greater. Conversely, non-pregnant dams continue to nurse their foals for a longer time (i.e., up to a year and a half, or even longer). In addition, it is worth noting that, in the event of foal death, some mares nurse their older offspring much longer (up to their third year) [37].

- The previous breeding status of the mare (i.e., mare with or without a yearling) can also be at stake: mares with a yearling and a foal of the year tend to wean the latter at about 8.5 months, while mares who did not have a foal in the previous year can wean the foal of the year at a later age (at about 16 months) [68].

- The maternal parity (i.e., primiparous/multiparous) can also influence the age of foals at weaning: thus, some primiparous mares (i.e., raising their first foals) nurse their foals over a longer period (on average of two extra months) as compared to multiparous mares [38]. This tendency, however, has not been systematically reported [37,49].

- Other potential factors affecting the timing of weaning include the availability of food resources, weather conditions or maternal body condition.

2.3.3. Cessation of Nursing, but no Rupture of the Dam-Foal Social Bond

3. A Study on Spontaneous Weaning in Domestic Foals

3.1. Subjects and Study Site

3.2. Observations

3.3. Analysis

3.4. Results

3.4.1. Age at Weaning and Factors of Variation

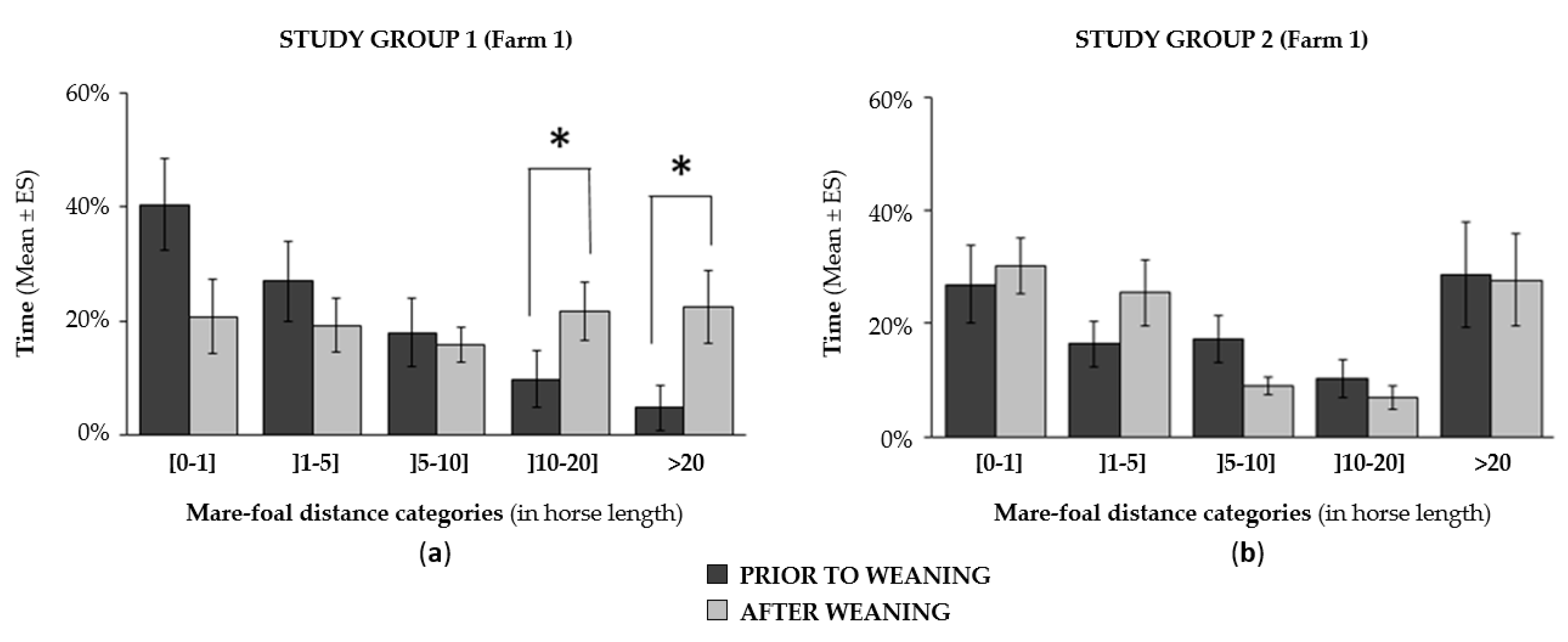

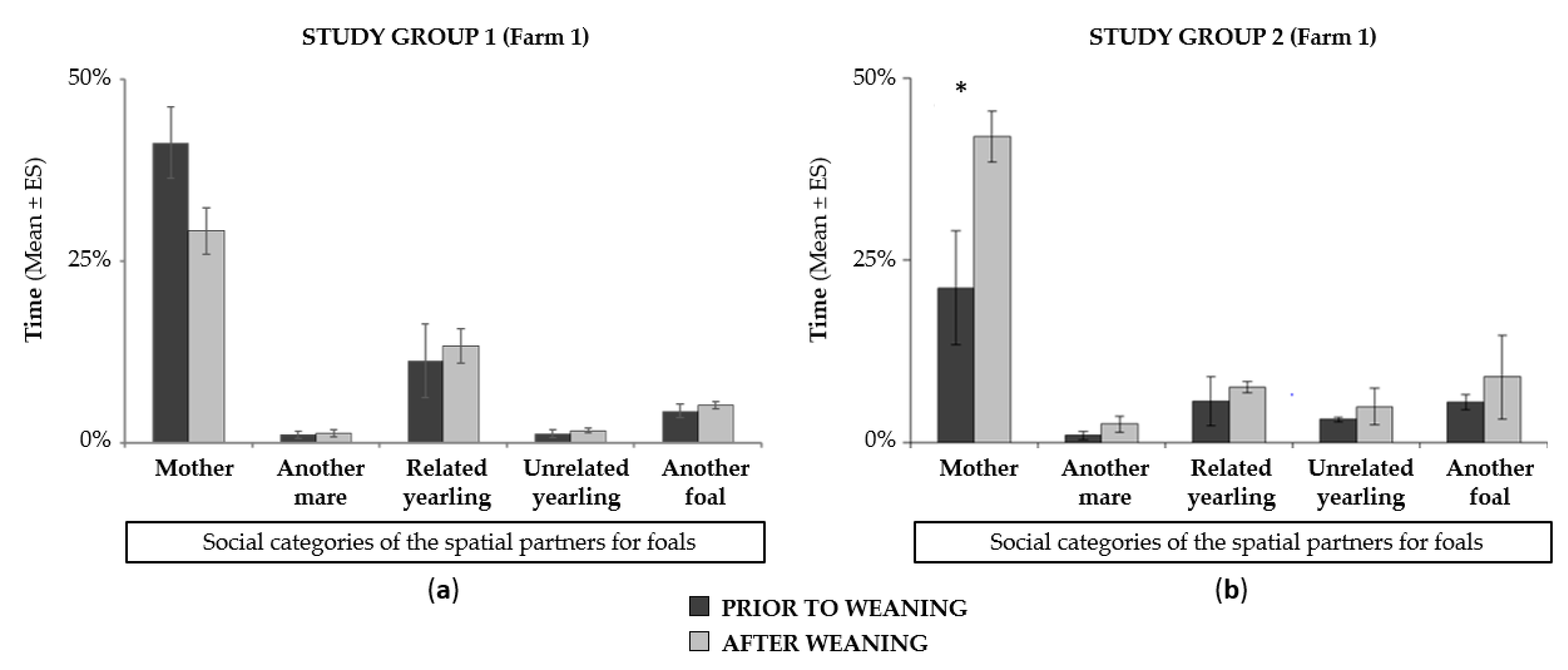

3.4.2. Impact of Weaning on Time-Budget and Dam-Offspring Relationship

3.5. Conclusions

4. General Discussion

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Apter, R.C.; Householder, D.D. Weaning and weaning management of foals: A review and some recommendations. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 1996, 16, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.; Goodwin, D.; Redhead, E.S. Survey of breeders’ management of horses in Europe, North America and Australia: Comparison of factors associated with the development of abnormal behavior. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 114, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waran, N.K.; Clarke, N.; Farnworth, M. The effects of weaning on the domestic horse (Equus caballus). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 110, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doreau, M.; Boulot, S. Recent knowledge on mare milk production: A review. Livest. Prod. Sci. 1989, 22, 213–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oftedal, O.T.; Hintz, H.F.; Schryver, H.F. Lactation in the horse: Milk composition and intake by foals. J. Nutr. 1983, 113, 2096–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, D.; Gibbs, P.G.; Potter, G.D. Milk energy production by lactating mares. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 1992, 12, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansade, L.; Bertrand, M.; Boivin, X.; Bouissou, M.F. Effects of handling at weaning on manageability and reactivity of foals. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2004, 87, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligout, S.; Bouissou, M.F.; Boivin, X. Comparison of the effects of two different handling methods on the subsequent behaviour of Anglo-Arabian foals toward humans and handling. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 113, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkies, K.; Dubois, C.; Marshall, K.; Parois, S.; Graham, L.; Haley, D. A two-stage method to approach weaning stress in horses using a physical barrier to prevent nursing. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 183, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreevy, P.; Berger, J.; de Brauwere, N.; Doherty, O.; Harrison, A.; Fiedler, J.; Jones, C.; McDonnell, S.; McLean, A.; Nakonechny, L.; et al. Using the Five Domains Model to Assess the Adverse Impacts of Husbandry, Veterinary, and Equitation Interventions on Horse Welfare. Animals 2018, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houpt, K.A.; Hintz, H.F.; Butler, W.R. A preliminary study of two methods of weaning foals. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1984, 12, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, R.M.; Kronfeld, D.S.; Holland, J.L.; Greiwe-Crandell, K.M. Preweaning diet and stall weaning method influences on stress response in foals. J. Anim. Sci. 1995, 73, 2922–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erber, R.; Wulf, M.; Rose-Meierhöfer, S.; Becker-Birck, M.; Möstl, E.; Aurich, J.; Hoffmann, G.; Aurich, C. Behavioral and physiological responses of young horses to different weaning protocols: A pilot study. Stress 2012, 15, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCall, C.A.; Potter, G.D.; Kreider, J.L. Locomotor, vocal and other behavioural responses to varying methods of weaning in foals. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1985, 14, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.L.; Kronfeld, D.S.; Hoffman, R.M.; Griewe-Crandell, K.M.; Boyd, T.L.; Cooper, W.L.; Harris, P. Weaning stress is affected by nutrition and weaning methods. Pferdeheilkunde 1996, 12, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heleski, C.R.; Shelle, A.C.; Nielsen, B.D.; Zanella, A.J. Influence of housing on weanling horse behavior and subsequent welfare. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2002, 78, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, S.; Zanella, A.J.; Sankey, C.; Richard-Yris, M.A.; Marko, A.; Hausberger, M. Adults may be used to alleviate weaning stress in domestic foals (Equus caballus). Physiol. Behav. 2012, 106, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Zhang, L.; Tuohut, A.; Shi, G.; Li, H. Effect of weaning age on stress-related behavior in foals (Equus Caballus) by Abrupt-Group Weaning Method. Phylogenetics Evol. Biol. 2015, 3, 151. [Google Scholar]

- McCall, C.A.; Potter, G.D.; Kreider, J.L.; Jenkins, W.L. Physiological responses in foals weaned by abrupt or gradual methods. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 1987, 7, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowski, K.; Hallquist, N.A.; Helyar, L.; Sherman, A.R.; Scanes, C.G. Effect of different separation protocols between mares and foals on plasma cortisol in cell-mediated immune response. Equine Vet. J. 1990, 10, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, N.; Foury, A.; Kittelmann, S.; Reigner, F.; Moroldo, M.; Ballester, M.; Esquerré, D.; Rivière, J.; Sallé, G.; Gérard, P.; et al. The effects of weaning methods on gut microbiota composition and horse physiology. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, J.M.; Spier, S.J.; Davies, R.; Gardner, I.A.; Leutenegger, C.M.; Bain, M. Behavioral and physiological responses of weaned foals treated with equine appeasing pheromone: A double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. J. Vet. Behav. 2013, 8, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gensollen, T.; Iyer, S.S.; Kasper, D.L.; Blumberg, R.S. How colonization by microbiota in early life shapes the immune system. Science 2016, 352, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, L.; Chen, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhuang, J.; Li, Q.; Feng, Z. Intestinal microbiota in early life and its implications on childhood health. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2019, 17, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waters, A.; Nicol, C.; French, N. Factors influencing the development of stereotypic and redirected behaviours in young horses: Findings of a four year prospective epidemiological study. Equine Vet. J. 2002, 34, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicol, C.J.; Badnell-Waters, A.J. Suckling behaviour in domestic foals and the development of abnormal oral behavior. Anim. Behav. 2005, 70, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newberry, R.C.; Swanson, J.C. Implications of breaking mother–young social bonds. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 110, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausberger, M.; Gautier, E.; Müller, C.; Jego, P. Lower learning abilities in stereotypic horses. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2007, 107, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmings, A.; McBride, S.D.; Hale, C.E. Perseverative responding and the aetiology of equine oral stereotypy. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2007, 104, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.; Redhead, E.S.; Goodwin, D.; McBride, S.D. Impaired instrumental choice in crib-biting horses (Equus caballus). Behav. Brain Res. 2007, 191, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolter, R. Alimentation du Cheval, 2nd ed.; France Agricole Editions: Paris, France, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Moons, C.P.H.; Laughlin, K.; Zanella, A.J. Effects of short-term maternal separations on weaning stress in foals. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2005, 91, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansade, L.; Foury, A.; Reigner, F.; Vidament, M.; Guettier, E.; Bouvet, G.; Soulet, D.; Parias, C.; Ruet, A.; Mach, N.; et al. Progressive habituation to separation alleviates the negative effects of weaning in the mother and foal. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018, 97, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, L.K.; Lawrence, L.M.; Parker, A.L.; Barnes, T.; Griffin, A.S. The effect of weaning age on foal growth and radiographic bone density. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 1998, 18, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurjónsdóttir, H.; van Dierendonck, M.; Snorrason, S.; Thórhallsdóttir, A.G. Social relationships in a group of horses without a mature stallion. Behaviour 2003, 140, 783–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feh, C. Relationships and communication in socially natural horse herds. In The Domestic Horse, the Evolution, Development and Management of Its Behavior; Mills, D.S., McDonnell, S.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; pp. 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, S.J. The behaviour and social organization of the New Forest ponies. Anim. Behav. Monogr. 1972, 5, 85–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, P.; Harvey, P.H.; Wells, S.M. On lactation and associated behaviour in a natural herd of horses. Anim. Behav. 1984, 32, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowell-Davis, S.; Weeks, J. Maternal behaviour and mare–foal interaction. In The Domestic Horse, the Evolution, Development and Management of Its Behavior; Mills, D.S., McDonnell, S.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; pp. 126–138. [Google Scholar]

- Waring, G.H. Horse Behavior, 3rd ed.; Noyes Publications, William Andrew Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell, S. Sexual behaviour. In The Domestic Horse, the Evolution, Development and Management of Its Behavior; Mills, D.S., McDonnell, S.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; pp. 110–125. [Google Scholar]

- Satué, K.; Felipe, M.; Mota, J.; Muñoz, A. Factors influencing gestational length in mares: A review. Livest. Sci. 2011, 136, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavatte, P. Twinning in the mare. Equine Vet. Educ. 1997, 6, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dierendonck, M.C.; Sigurjonsdottir, H.; Colenbrander, B.; Thorhallsdottir, A.G. Differences in social behaviour between late pregnant, post-partum and barren mares in a herd of Icelandic horses. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2004, 89, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estep, D.Q.; Crowell-Davis, S.L.; Earlcostello, S.A.; Beatey, S.A. Changes in the social-behavior of drafthorse (Equus caballus) mares coincident with foaling. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1993, 35, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingel, H. Social organization and reproduction in equids. J. Reprod Fertil. Suppl. 1975, 23, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Houpt, C. Formation and dissolution of mare-foal bond. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2002, 78, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, E.Z.; Stafford, K.J.; Linklater, W.L.; Veltman, C.J. Suckling behaviour does not measure milk intake in horses, Equus caballus. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1999, 57, 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowell-Davis, S.L. Nursing behaviour and maternal aggression among Welsh ponies (Equus caballus). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1985, 14, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, J.A.; Crowell-Davis, S.L. Maternal behavior of Belgian (Equus caballus) mares. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1994, 41, 161–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartošová, J.; Komárková, M.; Dubcová, J.; Bartoš, L.; Pluháček, J. Concurrent lactation and pregnancy: Pregnant domestic horse mares do not increase mother-offspring conflict during intensive lactation. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feist, J.D.; McCullough, D.R. Behaviour patterns and communication in feral horses. Z. Tierpsychol. 1976, 41, 337–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becvarova, I.; Buechner-Maxwell, V. Feeding the foal for immediate and long-term health. Equine Vet. J. Suppl. 2012, 41, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowell-Davis, S.L.; Houpt, K.A. Coprophagy by foals: Effect of age and possible functions. Equine Vet. J. 1985, 17, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis-Smith, K.; Wood-Gush, D.G.M. Coprophagia as seen in Thoroughbred foals. Equine Vet. J. 1977, 9, 155–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinier, S.L.; Alexander, A.J. Coprophagy as an avenue for foals of the domestic horse to learn food preferences from their dams. J. Theor. Biol 1995, 173, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, S.; Hemery, D.; Richard, M.A.; Hausberger, M. Human–mare relationships and behaviour of foals toward humans. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2005, 93, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, S.; Briefer, S.; Richard-Yris, M.A.; Hausberger, M. Are 6-month-old foals sensitive to dam’s influence? Dev. Psychobiol. 2007, 48, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowell-Davis, S.L. Spatial relations between mares and foals of the Welsh pony (Equus caballus). Anim. Behav. 1986, 34, 1007–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faubladier, C.; Sadet-Bourgeteau, S.; Philippeau, C.; Jacotot, E.; Julliand, V. Molecular monitoring of the bacterial community structure in foal feces pre- and post-weaning. Anaerobe 2014, 25, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, J.; Roediger, K.; Schroedl, W.; Aldaher, N.; Vervuert, I. Development of intestinal microflora and occurrence of diarrhoea in sucking foals: Effects of Bacillus cereus var. toyoi supplementation. BMC Vet. Res. 2015, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quercia, S.; Freccero, F.; Castagnetti, C.; Soverini, M.; Turroni, S.; Biagi, E.; Rampelli, S.; Lanci, A.; Mariella, J.; Chinellato, E.; et al. Early colonisation and temporal dynamics of the gut microbial ecosystem in Standardbred foals. Equine Vet. J. 2019, 51, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausberger, M.; Lansade, L.; Henry, S. Behaviour and behavioural management of horse behavior during breeding and stabling. In Equine Nutrition; Martin-Rosset, W., Ed.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Gelderland, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 505–512. [Google Scholar]

- Bourjade, M. Sociogenèse et Expression des Comportements Individuels et Collectifs chez le Cheval [Sociogeny and Manifestation of Individual and Collective Behaviours in Horses]. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Louis Pasteur Strasbourg, Strabourg, France, 23 November 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, A.; Hausberger, M. Behaviour of foals before weaning may have some genetic basis. Ethology 1994, 96, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, S.; Richard-Yris, M.A.; Tordjman, S.; Hausberger, M. Neonatal handling affects durably bonding and social development. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausberger, M.; Henry, S.; Larose, C.; Richard-Yris, M.A. First suckling: A crucial event for mother-young attachment? An experimental study in horses (Equus caballus). J. Compar. Psychol. 2007, 121, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J. Wild Horses of the Great Basin; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, E.Z.; Linklater, W.L. Individual mares bias investment in sons and daughters in relation to their condition. Anim. Behav. 2000, 60, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hausberger, M.; Richard-Yris, M.A. Individual differences in the domestic horse, origins, development and stability. In The Domestic Horse, the Evolution, Development and Management of Its Behavior; Mills, D.S., McDonnell, S.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; pp. 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Rutberg, A.T.; Keiper, R.R. Proximate causes of natal dispersal in feral ponies: Some sex differences. Anim. Behav. 1993, 46, 969–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, J. Observational study of behaviour: Sampling methods. Behaviour 1974, 49, 227–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaud, G.; Dubroeucq, H.; Rivot, D. Notation de L’état Corporel des Chevaux de Selle et de Sport [Body Condition Scoring for Saddle and Sport Horses]; Inra, Institut du cheval-Institut de l’Elevage: Paris, France, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, S.; Castellan, J. Nonparametric Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Benhajali, H.; Ezzaouia, M.; Lunel, C.; Charfi, F.; Hausberger, M. Temporal feeding pattern may influence reproduction efficiency, the example of breeding mares. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsesport. Available online: https://horsesport.com/magazine/nutrition/reducing-weaning-stress/ (accessed on 28 August 2016).

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss; Attachment, Basic: New York, NY, USA, 1969; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Harlow, H.F. The development of affectional patterns in infant monkeys. In Determinants of Infant Behaviour; Foss, B.M., Ed.; Wiley: Methuen, MA, USA; London, UK, 1961; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Harlow, H.F.; Harlow, M.K. The affectional systems. In Behavior of Nonhuman Primates: Modern Research Trends; Schrier, A.M., Harry, F., Harlow, F., Stollnitz, F., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1965; pp. 287–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryce, C.R.; Rüedi-Bettschen, D.; Dettling, A.C.; Weston, A.; Russig, H.; Ferger, B.; Feldon, J. Long-term effects of early-life environmental manipulations in rodents and primates: Potential animal models in depression research. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2005, 29, 649–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.W. Early-life object exposure with a habituated mother reduces fear reactions in foals. Anim. Cogn. 2016, 19, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhajali, H.; Richard-Yris, M.A.; Ezzaouia, M.; Charfi, F.; Hausberger, M. Reproductive status and stereotypies in breeding mares: A brief report. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2010, 128, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurjónsdóttir, H.; Haraldsson, H. Significance of Group Composition for the Welfare of Pastured Horses. Animals 2019, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camus, S.; Rochais, C.; Blois-Heulin, C.; Li, Q.; Hausberger, M. Birth origin differentially affects depressive-like behaviours: Are captive-born cynomolgus monkeys more vulnerable to depression than their wild-born counterparts? PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, F.D. Behavioral and psychological outcomes for dogs sold as puppies through pet stores and/or born in commercial breeding establishments: Current knowledge and putative causes. J. Vet. Behav. 2017, 19, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurt, M.B.S.; Stella, J.; Croney, C. Available online: https://extension.purdue.edu/extmedia/VA/VA-11-W.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2020).

- Weary, D.M.; Jasper, J.; Hötzel, M.J. Understanding weaning distress. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 110, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | Study Group 1 | Study Group 2 | Study Group 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group size | 24 | 25 | 47 |

| Density (number of horses per hectare) | 1.10 | 1.32 | 2.35 |

| Number of mare-foal pairs | 5 | 4 | 7 |

| Breeding mares: | |||

| Mean age ± ES 1 [min-max] (in years) | 14.8 ± 2.9 [8–23] | 10.8 ± 2.2 [7–17] | 13.0 ± 2.1 [9–23] |

| Mean number ± ES 1 of previous foals [min-max] | 5.6 ± 2.2 [2–14] | 5.5 ± 1.9 [2–11] | 4.7 ± 1.4 [2–11] |

| Foals: | |||

| Number of females/males | 4/1 | 3/1 | 2/5 |

| Birthdate [min-max] | [20/05–21/06] | [06/06–22/07] | [29/05–14/07] |

| FOALS | MARES | WEANING | FETUS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | Sex | Age (years) | Parity | Conception rate 1 | Age (months) | Dry period (months) | Fetal sex | |

| GROUP 1 | G1F1 | F | 19 | 2 | 1.0 | 9.2 | 3.5 | F |

| G1F2 | F | 23 | 13 | 0.7 | 9.3 | 2.9 | F | |

| G1M1 | M | 9 | 3 | 0.7 | 9.1 | 3.0 | M | |

| G1F3 | F | 8 | 2 | 1.0 | 8.8 | 3.7 | F | |

| G1F4 | F | 15 | 8 | 1.0 | 10.0 | 1.9 | F | |

| GROUP 2 | G2F1 | F | 9 | 4 | 1.0 | 8.1 | 3.8 | M |

| G2F2 | F | 17 | 11 | 0.9 | 8.5 | 3.2 | F | |

| G2F3 | F | 10 | 5 | 0.8 | 9.6 | 2.4 | M | |

| G2M1 | M | 7 | 2 | 1.0 | 7.7 | 3.9 | M | |

| GROUP 3 | G3M1 | M | 23 | 11 | 1.0 | 9.3 | 4.3 | F |

| G3M2 | M | 10 | 2 | 0.8 | 9.8 | 2.7 | F | |

| G3M3 | M | 11 | 3 | 1.0 | 9.7 | 2.8 | M | |

| G3M4 | M | 9 | 3 | 1.0 | 8.7 | 3.6 | F | |

| G3M5 | M | 11 | 3 | 1.0 | 8.7 | 3.1 | F | |

| G3F1 | F | 13 | 6 | 0.8 | 9.2 | 2.2 | F | |

| G3F2 | F | 19 | 10 | 1.0 | 7.8 | 4.6 | F | |

| ALL | Mean ± ES | 13.3 ± 1.3 | 5.5 ± 1.0 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 9.0 ± 0.2 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | ||

| CV (%) | 40.0% | 69.6% | 14.4% | 7.7% | 22.9% | |||

| Variables | Study Group 1 | Study Group 2 | Study Group 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age at weaning (in months) | 9.3 ± 0.2 | 8.5 ± 0.4 | 9.0 ± 0.3 |

| [Min-Max] (in months) | [8.8–10.0] | [7.7–9.6] | [7.8–9.8] |

| CV (%) | 4.8% | 9.7% | 7.7% |

| Duration of the dry period (in months) | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 3.3 ± 0.3 |

| [Min-Max] (in months) | [1.9–3.7] | [2.4–3.9] | [2.2–4.6] |

| CV (%) | 23.3% | 20.2% | 26.1% |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Henry, S.; Sigurjónsdóttir, H.; Klapper, A.; Joubert, J.; Montier, G.; Hausberger, M. Domestic Foal Weaning: Need for Re-Thinking Breeding Practices? Animals 2020, 10, 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10020361

Henry S, Sigurjónsdóttir H, Klapper A, Joubert J, Montier G, Hausberger M. Domestic Foal Weaning: Need for Re-Thinking Breeding Practices? Animals. 2020; 10(2):361. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10020361

Chicago/Turabian StyleHenry, Séverine, Hrefna Sigurjónsdóttir, Aziliz Klapper, Julie Joubert, Gabrielle Montier, and Martine Hausberger. 2020. "Domestic Foal Weaning: Need for Re-Thinking Breeding Practices?" Animals 10, no. 2: 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10020361

APA StyleHenry, S., Sigurjónsdóttir, H., Klapper, A., Joubert, J., Montier, G., & Hausberger, M. (2020). Domestic Foal Weaning: Need for Re-Thinking Breeding Practices? Animals, 10(2), 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10020361