Soiling of Pig Pens: A Review of Eliminative Behaviour

Simple Summary

Abstract

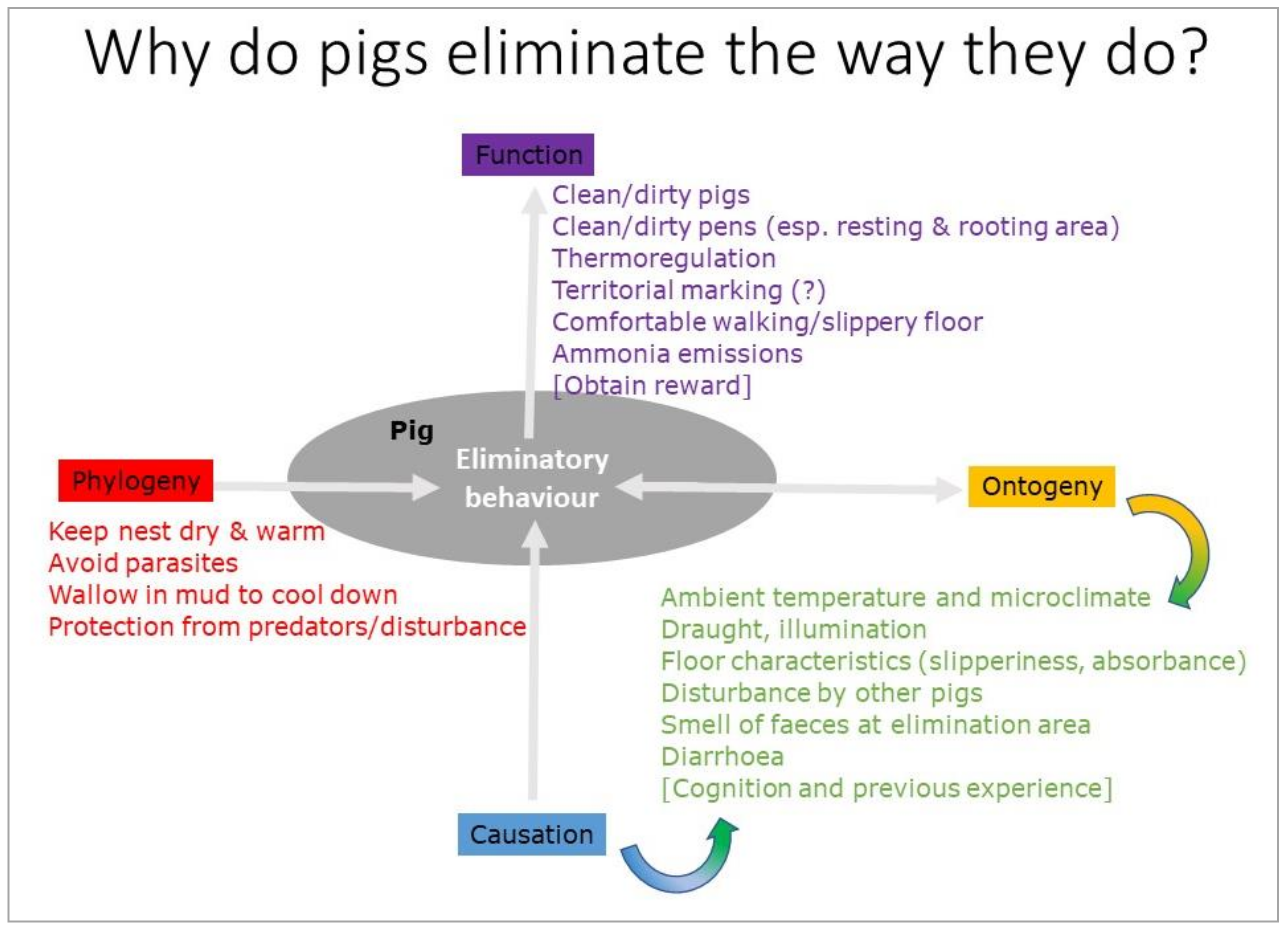

1. Introduction

2. Normal Eliminative Behaviour

2.1. Phylogeny

2.2. Ontogeny

2.3. Causation/Mechanism

2.4. Function

3. Pen Soiling in Current Systems: A Disease Framework

3.1. Definition

3.2. Aetiology

3.3. Symptoms

3.4. Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

3.5. Pathogenesis

3.6. Treatment and Prevention of Pen Soiling in Existing Systems

- (1)

- The first is to reduce the desirability of the (intended) elimination area as a resting area. One example is the use of studs in the elimination area to prevent pigs from resting there. Aarnink et al. [73] reported reduced lying in the elimination area, reduced soiling of the solid floor, and reduced ammonia emissions with metal studs (cylindrical studs, 5 cm high, 2 cm in diameter, spaced at 20 cm) installed in the elimination area. A less clear example may be installing drinkers in the slatted area [39]. Spillage of water results in a wet, cooler floor that, depending on the temperature, may cause pigs to lie away from it, making it more suitable for elimination. However, pigs may also avoid excreting in proximity of the drinkers because of the elevated level of activity in this area.

- (2)

- The second more welfare-friendly approach is to improve the suitability of other areas in the pen to be used for their specific function, such as resting and activity, instead of reducing the (resting) comfort of the elimination area [25,26]. When kept indoors, this could include, for example, providing enrichment materials in the activity area, installing partitions to help the pigs differentiate between different functional areas, and improving the comfort in the lying area. For example, Huynh et al. [42] found that at high ambient temperatures, the use of a floor cooling system embedded in the solid floor resulted in cleaner pens, fewer pigs lying on the slatted floor, and a better feed intake and growth rate. Similarly, water sprinklers resulted in a drop in temperature near the water nipples and less soiling [74]. When bedding or rooting materials are provided, pigs will tend to eliminate away from them. In rearing systems with outdoor access, Vermeer et al. [34] observed that an outdoor rooting area resulted in improved cleanliness of the whole pen (although in some cases the rooting area was also used as a dunging area), leaving the straw-bedded indoor-area clean and dry. Additionally, Olsen et al. [36] found that in pens with an outdoor run, most dunging took place outside, away from the lying and roughage feeding area. Huynh et al. [75] found that providing an outdoor yard (2.5 × 2 m) to pig pens (2.5 × 3 m) containing groups of 5 pigs in a tropical climate reduced the number of eliminations in the resting area, and that adding an indoor wallow had a similar effect (especially when no yard was provided). Improving one type of comfort, e.g., cushioning in the lying area, might, however, also have drawbacks in other respects. For example, Savary et al. [76] observed that at higher temperatures, synthetic plates and straw in the bedding area resulted in more pen soiling because the pigs choose to lie in the elimination area, to cool down. This is also in line with Fraser [77], who demonstrated that pigs only showed a preference for straw bedding over concrete at low temperatures.

- (3)

- The third approach to deal with pen soiling is to reduce the suitability of other functional areas as an area for elimination. Rearing pigs at high stocking densities poses a general obstacle for the separation of functional areas. So, in general, reducing high stocking densities could counteract pen soiling in existing systems. However, in some conditions, e.g., in young pigs, excessive space allowance in the lying area may increase the risk of pen soiling. In such cases, farmers may (temporarily) reduce the size of the resting area or increase the stocking density, even though this may not always be the most welfare-friendly strategy. Randall et al. [27] observed that in conventionally-kept finishing pigs, a stocking density between 120 and 130 kg/m2 resulted in a cleaner lying area as compared to both a higher and lower density. While overcrowding may block access to a separate elimination area away from other pigs, too much space in the assigned resting area may give pigs the (false) impression they have moved away far enough from the area used for resting [26]. With abundant space in the resting area, pigs often defecate in unoccupied corners or against walls [78], and once a location has become soiled it may be more likely to be used for elimination in the future [64].

- (4)

- The fourth and final way to steer eliminative behaviour is to make the intended elimination area more attractive as a dunging place, e.g., using olfactory, optical, and/or auditory cues. For example, contact with neighbouring pigs or even an open view to the surroundings may be used [50], as well as the temporal association between elimination and other behaviours, especially feeding and drinking. Hacker et al. [35] found that pens with closed partitions were cleaner than pens with open partitions, regardless of the water position, ambient temperature (up to 30 °C), and stocking density. In this study, closed pen partitions presumably reduced air drafts around the sleeping area and maintained a temperature gradient between the warmer lying area and the cooler (slatted) dunging area. Furthermore, open partitions in the slatted area may stimulate pigs to mark that area of the pen with dung, thus possibly indicating territorial limits to their neighbours, although there is no clear conclusion on whether pigs are territorial or not [25]. Areas close to open partitions could also be uncomfortable as a lying area, due to a disturbance of resting behaviour by the presence or activity of pigs in the neighbouring pens (André Aarnink, personal communication), or because pigs like to use a closed pen wall to lie down [79]. On the other hand, it is also noteworthy that closed partitions may provide a protected place for elimination, which may be preferred by the pigs. Therefore, the use of open or closed partitions may vary depend on the microclimatic conditions in the pen, on pen design and layout, and on the need to delimitate the resting area and/or the elimination area.

- (1)

- Be alert for early signs of pen soiling, especially by noting changes in resting behaviour, and take action at an early stage (e.g., by pen cleaning and providing saw dust in the resting area);

- (2)

- Avoid excessive stocking densities, in order to facilitate the distinction between functional areas;

- (3)

- Improve thermal comfort, especially in the designated resting area, e.g., by checking the ventilation system, reducing draughts, and optimising the microclimate (e.g., by floor cooling);

- (4)

- When animals are allocated to a new pen, favour the correct distinction between elimination and resting areas (e.g., by wetting the designated elimination area and providing dry feed or sawdust on the floor of the expected resting area for at least the first few days) [27];

- (5)

- Remove (or limit) olfactory clues as much as possible by thorough pen cleaning before introducing a new group of animals (Herman Vermeer, personal communication). Alternatively, explore the possibilities to direct them towards the correct dunging area by using olfactory cues;

- (6)

- Provide proper enrichment materials facilitating the use of functional areas, e.g., by enhanced synchronisation of behaviour (synchronised activity and rest), by stimulating activity in areas at risk of pen soiling, and perhaps adding lying comfort in the resting area (cushioning from bedding materials). For instance, providing some exploration material (fresh straw, roughage) or nutrition (e.g., grain, corn, lucerne) in the lying area at times appropriate for activity, e.g., during inspection of the pigs, in order to prevent the lying area from being used as an elimination area.

3.7. Importance of Pen Soiling

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hartung, J. A short history of livestock. Production Livestock Housing; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 21–34. ISBN 978-90-8686-217-7. [Google Scholar]

- Lassen, J.; Sandøe, P.; Forkman, B. Happy pigs are dirty–conflicting perspectives on animal welfare. Livest. Sci. 2006, 103, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørkhaug, H.; Richards, C.A. Multifunctional agriculture in policy and practice? A comparative analysis of Norway and Australia. J. Rural Stud. 2008, 24, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, P.H. Is the Netherlands Still Loving its Pig Farmer? Available online: https://www.volkskrant.nl/kijkverder/v/2019/houdt-nederland-nog-wel-van-zijn-varkensboer (accessed on 8 October 2019).

- Commandeur, M.A.M. Styles of Pig Farming-A Techno-Sociological Inquiry of Processes and Constructions in Twente and the Achterhoek; Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R. Animal Machines: The New Factory Farming Industry; Vincent Stuart Ltd.: London, UK, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Brambell, R. Report of the Technical Committee to Inquire into the Welfare of Animals Kept under Intensive Livestock Husbandry Systems-Cmnd; Her Majesty’s Stationery Office: London, UK, 1965; p. 85. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, P. Animal Liberation: A New Ethics for Our Treatment of Animals; New York Review Book: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Pennings, M. Hundreds of Accidents of Cattle and Pigs Falling into Manure Pit. BNN-Vara, Zembla. Available online: https://www.bnnvara.nl/zembla/artikelen/honderden-ongelukken-met-runderen-en-varkens-die-in-mestput-vallen (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Tuyttens, F.A.M. The importance of straw for pig and cattle welfare: A review. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2005, 92, 261–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, D. The effect of straw on the behaviour of sows in tether stalls. Anim. Sci. 1975, 21, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracke, M.B.M. Chapter 6-Chains as proper enrichment for intensively-farmed pigs. In Advances in Pig Welfare; Špinka, M., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Duxford, UK, 2018; pp. 167–197. ISBN 978-0-08-101012-9. [Google Scholar]

- Bracke, M.B.M.; Koene, P. Expert opinion on metal chains and other indestructible objects as proper enrichment for intensively-farmed pigs. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NVWA Hokverrijking voor Varkens Blijft Speerpunt NVWA. Nieuwsbericht. Available online: https://www.nvwa.nl/nieuws-en-media/nieuws/2019/10/25/hokverrijking-voor-varkens-blijft-speerpunt-nvwa (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Meyer-Hamme, S.E.K.; Lambertz, C.; Gauly, M. Does group size have an impact on welfare indicators in fattening pigs. Animal 2016, 10, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KilBride, A.L.; Gillman, C.E.; Ossent, P.; Green, L.E. A cross-sectional study of the prevalence and associated risk factors for capped hock and the associations with bursitis in weaner, grower and finisher pigs from 93 commercial farms in England. Prev. Vet. Med. 2008, 83, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokma-Bakker, M.H.; Hagen, R.R.; Bokma, S.; Bremmer, B.; Ellen, H.H.; Hopster, H.; Neijenhuis, F.; Vermeij, I.; Weges, J. Knelpunten en verbetermogelijkheden—Onderzoek naar Brandveiligheid voor Dieren in Veestallen; Wageningen Livestock Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2012; Available online: http://library.wur.nl/WebQuery/wurpubs/fulltext/246894 (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Bokma-Bakker, M.; Welfare, L.-A.B.; Bokma, S.; Ellen, H.; Hagen, R.; Van Ruijven, C.; Omgeving, L.-V.E. Evaluatie Actieplan Stalbranden 2012–2016; Wageningen University and Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dourmad, J.Y.; Ryschawy, J.; Trousson, T.; Bonneau, M.; Gonzàlez, J.; Houwers, H.W.J.; Hviid, M.; Zimmer, C.; Nguyen, T.L.T.; Morgensen, L. Evaluating environmental impacts of contrasting pig farming systems with life cycle assessment. Animal 2014, 8, 2027–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, W.; Cranen, I. Themaboek Biologische Varkenshouderij; Wageningen University and Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, A.-C.; Jeppsson, K.-H.; Botermans, J.; von Wachenfelt, H.; Andersson, M.; Bergsten, C.; Svendsen, J. Pen hygiene, N, P and K budgets and calculated nitrogen emission for organic growing–finishing pigs in two different housing systems with and without pasture access. Livest. Sci. 2014, 165, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geers, R. Lying behaviour (location, posture and duration). In On Farm Monitoring of Pig Welfare; Verlarde, A., Geers, R., Eds.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 19–24. ISBN 9789086860258. [Google Scholar]

- Grimberg-Henrici, C.G.E.; Büttner, K.; Ladewig, R.Y.; Burfeind, O.; Krieter, J. Cortisol levels and health indicators of sows and their piglets living in a group-housing and a single-housing system. Livest. Sci. 2018, 216, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bøe, K.E.; Kvaal, I.; Hall, E.J.S.; Cronin, G.M. Individual differences in dunging patterns in loose-housed lactating sows. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. A Anim. Sci. 2016, 66, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, H.M.-L.; Kongsted, A.G.; Jakobsen, M. Pig elimination behavior-A review. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2020, 222, 104888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M.L.V.; Bertelsen, M.; Pedersen, L.J. Review: Factors affecting fouling in conventional pens for slaughter pigs. Animal 2018, 12, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, J.M.; Armsby, A.W.; Sharp, J.R. Cooling gradients across pens in a finishing piggery: II. Effects on excretory behaviour. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 1983, 28, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinbergen, N. On aims and methods of Ethology. Z. Tierpsychol. 1963, 20, 410–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanged, G.; Jensen, P. Behaviour of semi-naturally kept sows and piglets (except suckling) during 10 days postpartum. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1991, 31, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whatson, T.S. Development of eliminative behaviour in piglets. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1985, 14, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolba, A.; Wood-Gush, D.G.M. The behaviour of pigs in a semi-natural environment. Anim. Sci. 1989, 48, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petherick, C.J. A note on the space use for excretory behaviour of suckling piglets. Appl. Anim. Ethol. 1983, 9, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchenauer, D.; Luft, C.; Grauvogl, A. Investigations on the eliminative behaviour of piglets. Appl. Anim. Ethol. 1982, 9, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeer, H.M.; Altena, H.; Vereijken, P.F.G.; Bracke, M.B.M. Rooting area and drinker affect dunging behaviour of organic pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2015, 165, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacker, R.R.; Ogilvie, J.R.; Morrison, W.D.; Kains, F. Factors affecting excretory behavior of pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 1994, 72, 1455–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, A.W.; Dybkjær, L.; Simonsen, H.B. Behaviour of growing pigs kept in pens with outdoor runs: II. Temperature regulatory behaviour, comfort behaviour and dunging preferences. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2001, 69, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, N.; Prescott, N.; Perry, G.; Potter, M.; Le Sueur, C.; Wathes, C. Preference of growing pigs for illuminance. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2006, 96, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, B.; Bachmann, I. A sequential analysis of eliminative behaviour in domestic pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1998, 56, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, S. Intensive Pig Production: Environmental Management and Design; Granada Publishing: London, UK, 1984; p. 588. [Google Scholar]

- AHDB A Practical Guide to Environmental Enrichment for Pigs-A Handbook for Pig Farmers. Available online: //ahdb.org.uk/knowledge-library/environmental-enrichment-for-pigs (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Bracke, M.B.M. Multifactorial testing of enrichment criteria: Pigs ‘demand’ hygiene and destructibility more than sound. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2007, 107, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.T.T.; Aarnink, A.J.A.; Spoolder, H.A.M.; Verstegen, M.W.A.; Kemp, B. Effects of floor cooling during high ambient temperatures on the lying behavior and productivity of growing finishing pigs. Trans. ASAE 2004, 47, 1773–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, J.M.; Clark, J.J. Models of heat production and critical temperature for growing pigs. Anim. Sci. 1979, 28, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haer, L.C.M. Relevance of Eating Pattern for Selection of Growing Pigs. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Eissen, J. Breeding for Feed Intake Capacity in Pigs. PhD Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Aarnink, A.J.A.; Schrama, J.W.; Heetkamp, M.J.W.; Stefanowska, J.; Huynh, T.T.T. Temperature and body weight affect fouling of pig pens. J. Anim. Sci. 2006, 84, 2224–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillmann, E.; Mayer, C.; Schrader, L. Lying behaviour and adrenocortical response as indicators of the thermal tolerance of pigs of different weights. Anim. Welf. 2004, 13, 329–335. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh, T.T.T.; Aarnink, A.J.A.; Gerrits, W.J.J.; Heetkamp, M.J.H.; Canh, T.T.; Spoolder, H.A.M.; Kemp, B.; Verstegen, M.W.A. Thermal behaviour of growing pigs in response to high temperature and humidity. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2005, 91, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.T.T.; Aarnink, A.J.A.; Verstegen, M.W.A.; Gerrits, W.J.J.; Kemp, B.; Heetkamp, M.J.W.; Canh, T.T. Effects of increasing temperatures on physiological changes in pigs at different relative humidities1. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 83, 1385–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damm, B.I.; Pedersen, L.J. Eliminative Behaviour in Preparturient Gilts Previously Kept in Pens or Stalls. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. A Anim. Sci. 2000, 50, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocepek, M.; Goold, C.M.; Busančić, M.; Aarnink, A.J.A. Drinker position influences the cleanness of the lying area of pigs in a welfare-friendly housing facility. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 198, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, D.; Courboulay, V.; Manteca, X.; Velarde, A.; Dalmau, A. The welfare of growing pigs in five different production systems: Assessment of feeding and housing. Animal 2012, 6, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracke, M.B.M.; Rodenburg, T.B.; Vermeer, H.M.; Van Niekerk, T.G.C.M. Towards a Common Conceptual Framework and Illustrative Model for Feather Pecking in Poultry and Tail Biting in Pigs: Connecting Science to Solutions. Available online: http://www.henhub.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Henhub-pap-models-mb-090218-for-pdf.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Larsen, M.L.V.; Bertelsen, M.; Pedersen, L.J. Pen Fouling in Finisher Pigs: Changes in the Lying Pattern and Pen Temperature Prior to Fouling. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welfare Quality Assessment Protocol for Pigs. Available online: http://www.welfarequalitynetwork.net/media/1018/pig_protocol.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Vermeer, H.M.; Hopster, H. Operationalizing Principle-Based Standards for Animal Welfare-Indicators for Climate Problems in Pig Houses. Animals 2018, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maw, S.J.; Fowler, V.R.; Hamilton, M.; Petchey, A.M. Effect of husbandry and housing of pigs on the organoleptic properties of bacon. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2001, 68, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrey, L.; Kemper, N.; Fels, M. Behaviour and skin injuries of sows kept in a novel group housing system during lactation. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2018, 46, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fels, M.; Lüthje, F.; Faux-Nightingale, A.; Kemper, N. Use of space and behavior of weaned piglets kept in enriched two-level housing system. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2018, 21, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courboulay, V. Cleanliness. In On Farm Monitoring of Pig Welfare; Verlarde, A., Geers, R., Eds.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 117–120. ISBN 9789086860258. [Google Scholar]

- Petherick, J.C. Spatial requirements of animals: Allometry and beyond. J. Vet. Behav. 2007, 2, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Meer, Y.; Lammers, A.; Jansman, A.J.M.; Rijnen, M.M.J.A.; Hendriks, W.H.; Gerrits, W.J.J. Performance of pigs kept under different sanitary conditions affected by protein intake and amino acid supplementation. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 94, 4704–4719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova-Peneva, S.G.; Aarnink, A.J.A.; Verstegen, M.W.A. Ammonia emissions from organic housing systems with fattening pigs. Biosyst. Eng. 2008, 99, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Dapeng, L.; Xiong, S.; Zhengxiang, S. Effects of inductive methods on dunging behavior of weaning pigs in slatted floor pens. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2016, 9, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydhmer, L. Welfare of boars. In Pigs Welfare in Practice (Animal Welfare in Practice); Camerlink, I., Manteca Vilanova, X., Eds.; 5m Publishing: Sheffield, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, K.; Chennells, D.J.; Armstrong, D.; Taylor, L.; Gill, B.P.; Edwards, S.A. The welfare of finishing pigs under different housing and feeding systems: Liquid versus dry feeding in fully-slatted and straw-based housing. Anim. Welf. 2007, 16, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, K.; Chennells, D.J.; Campbell, F.M.; Hunt, B.; Armstrong, D.; Taylor, L.; Gill, B.P.; Edwards, S.A. The welfare of finishing pigs in two contrasting housing systems: Fully-slatted versus straw-bedded accommodation. Livest. Sci. 2006, 103, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, C.T. The Science and Practice of Pig Production, 2nd ed; Blackwell Science: Oxford, UK, 1998; ISBN 0-632-05086-1. [Google Scholar]

- Mount, L.E. Adaptation to Thermal Environment. Man and his Productive Animals; Edward Arnold Ltd.: London, UK, 1979; ISBN 0713127406. [Google Scholar]

- Yousef, M.K. Thermoneutral zone. In Stress Physiology in Livestock; Yousef, M.K., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1985; pp. 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bracke, M.B.M.; Herskin, M.S.; Marahrens, M.; Gerritzen, M.A.; Spoolder, H.A.M. Review of Climate Control and Space Allowance During Transport of Pigs. Report of the EURCAW-Pigs. Available online: https://www.eurcaw.eu/en/eurcaw-pigs/dossiers/climate-control-and-space-allowance.htm (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Aarnink, A.J.A.; Huynh, T.T.T.; Bikker, P. Modelling heat production and heat loss in growing-finishing pigs. In Proceedings of the CIGR-AgEng Conference, Aarhus, Denmark, 26–29 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Aarnink, A.J.A.; Swierstra, D.; Van den Berg, A.J.; Speelman, L. Effect of Type of Slatted Floor and Degree of Fouling of Solid Floor on Ammonia Emission Rates from Fattening Piggeries. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 1997, 66, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, D.B.; Kristensen, A.R. Temperature as a predictor of fouling and diarrhea in slaughter pigs. Livest. Sci. 2016, 183, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.T.T.; Aarnink, A.J.A.; Truong, C.T.; Kemp, B.; Verstegen, M.W.A. Effects of tropical climate and water cooling methods on growing pigs’ responses. Livest. Sci. 2006, 104, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savary, P.; Gygax, L.; Wechsler, B.; Hauser, R. Effect of a synthetic plate in the lying area on lying behaviour, degree of fouling and skin lesions at the leg joints of finishing pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 118, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, D. Selection of bedded and unbedded areas by pigs in relation to environmental temperature and behaviour. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1985, 14, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarnink, A.J.A.; Koetsier, A.C.; Van den Berg, A.J. Dunging and lying behaviour of fattening pigs in relation to pen design and ammonia emission. In Proceedings of the Livestock Environment IV: Fourth International Symposium, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK, 6–9 July 1993; Collins, E., Boon, C., Eds.; ASAE Publication 03-93. Volume 4, pp. 1176–1184. [Google Scholar]

- Damm, B.I.; Moustsen, V.; Jørgensen, E.; Pedersen, L.J.; Heiskanen, T.; Forkman, B. Sow preferences for walls to lean against when lying down. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2006, 99, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova-Peneva, S.G.; Aarnink, A.J.A.; Verstegen, M.W.A. Ammonia and Mineral Losses on Dutch Organic Farms with Pregnant Sows. Biosyst. Eng. 2006, 93, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houwers, H.W.J.; Vermeer, H.M. Vertraging van Biologische Zeugen naar de Weide om Mineralenverlies te Verminderenm Research Report. 2009. Available online: http://edepot.wur.nl/5302 (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Ekesbo, I.; Gunnarson, S. Farm Animal Behaviour-Characteristics for Assessment of Health and Welfare; CABI: Wallingford, Oxfordshire, UK, 2018; ISBN 9781786391391. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan, A. Can Cattle be Trained to Urinate and Defecate in Specific Areas? An Exploration of Cattle’s Urination and Defecation Habits and Some Aspects of Learning Abilities. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fritschen, R.D.; Muehling, A.J. Space Requirements for Swine. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2672&context=extensionhist (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Jensen, T.; Kold Nielsen, C.; Vinther, J.; D’Eath, R.B. The effect of space allowance for finishing pigs on productivity and pen hygiene. Livest. Sci. 2012, 149, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaudeau, D. Effect of housing conditions (clean vs. dirty) on growth performance and feeding behavior in growing pigs in a tropical climate. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2009, 41, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC Council Directive 2008 120 EC of 18 December 2008 laying down minimum standards for the protection of pigs. Off. J. Eur. Union 2008, L47, 5–13.

- EC Commission Recommendation (EU) 2016 336 of 8 March 2016 on the application of Council Directive 2008/120/EC laying down minimum standards for the protection of pigs as regards measures to reduce the need for tail-docking. Off. J. Eur. Union 2016, L62, 20–22.

- Aarnink, A.J.A.; Van den Berg, A.J.; Keen, A.; Hoeksma, P.; Verstegen, M.W.A. Effect of Slatted Floor Area on Ammonia Emission and on the Excretory and Lying Behaviour of Growing Pigs. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 1996, 64, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, J.; Hermansen, J.E.; Strudsholm, K.; Kristensen, K. Potential loss of nutrients from different rearing strategies for fattening pigs on pasture. Soil Use Manag. 2006, 22, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Definition | Pigs and/or pig pens get unduly soiled with faeces or urine, usually due to a change in lying behaviour. No agreed standard as to what is undue soiling, and how to measure it. |

| Aetiology (Main Cause) | Inadequate thermoregulation (overheated/draughty lying area), faulty pen design (disturbance during elimination), flooring issues (dirty/slippery floors). |

| Symptoms | Pig and pen soiling (mostly seen at the same time) can be a “signal indicator” related to reduced animal welfare caused by climatic conditions. Additional symptoms: resting in the dunging area, panting due to heat stress, restlessness, lying on the slatted floor also at low ambient temperature, impaired animal health (increased transmission of gastrointestinal pathogens and parasites). |

| Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis | An operational definition is needed for a clear diagnosis (e.g., different functional areas and system specifications (e.g., floor type) may determine when a pen is classified as soiled). Differential diagnosis: faecal soiling to be distinguished from mud, enrichment substrate (earth, peat, compost), feed, diarrhoea, dark skin colour, skin disorders (e.g., greasy pig disease). |

| Pathogenesis | Three possible mechanisms:

|

| Treatment and Prevention * | General advice for farmers to deal with pen soiling in existing systems: Be alert for early signs (e.g., changes in resting behaviour), and take action at an early stage (e.g., clean pens and provide bedding in the resting area); Improve thermal comfort, esp. in the designated resting area (check the ventilation system, reduce draughts, and optimise the microclimate); In newly formed pens, favour the correct distinction between elimination and resting areas (floor of the designated elimination area can be wetted, and dry feed or sawdust can be provided on the floor of the expected resting area during the first few days); Remove (or limit) olfactory clues in the expected resting area as much as possible (thorough pen cleaning before introducing a new group of animals), provide smell of faeces in the designated dunging area; Provide proper enrichment materials to facilitate the distinction of functional areas (to stimulate activity in areas at risk of pen soiling) and if possible, add bedding materials in the resting area (to improve comfort). |

| Importance | Reported prevalence: 4–9% of pens. Pen soiling indicates, by itself, reduced animal welfare (i.e., rearing conditions overriding pigs’ motivation/tendency to keep the lying area clean). Poor hygiene may reduce growth rates, compromise health, reduce welfare and air quality. Legislation requires pigs to be kept in a thermally comfortable, adequately drained and clean area which allows all the animals to lie at the same time. Reducing pen soiling and/or a “pig toilet” could reduce the environmental impact of pig farming, and further improve pig welfare (e.g., by providing straw or roughage on a solid floor) in the future. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nannoni, E.; Aarnink, A.J.A.; Vermeer, H.M.; Reimert, I.; Fels, M.; Bracke, M.B.M. Soiling of Pig Pens: A Review of Eliminative Behaviour. Animals 2020, 10, 2025. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10112025

Nannoni E, Aarnink AJA, Vermeer HM, Reimert I, Fels M, Bracke MBM. Soiling of Pig Pens: A Review of Eliminative Behaviour. Animals. 2020; 10(11):2025. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10112025

Chicago/Turabian StyleNannoni, Eleonora, André J.A. Aarnink, Herman M. Vermeer, Inonge Reimert, Michaela Fels, and Marc B.M. Bracke. 2020. "Soiling of Pig Pens: A Review of Eliminative Behaviour" Animals 10, no. 11: 2025. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10112025

APA StyleNannoni, E., Aarnink, A. J. A., Vermeer, H. M., Reimert, I., Fels, M., & Bracke, M. B. M. (2020). Soiling of Pig Pens: A Review of Eliminative Behaviour. Animals, 10(11), 2025. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10112025