Isolation and Screening of Hydrogen-Oxidizing Bacteria from Mangrove Sediments for Efficient Single-Cell Protein Production Using CO2

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Strain Enrichment

2.2. Isolation and Identification of Strains

2.3. Optimization of Cultivation Conditions

2.3.1. Optimization of Initial pH and Temperature

2.3.2. Optimization of Nitrogen Source

2.3.3. Optimization of Oxygen Concentration

2.3.4. Effect of Auxiliary Energy Sources

2.3.5. Optimization of the Medium Composition by RSM

2.4. Analytical Methods

2.4.1. Genome Sequencing and Analysis

2.4.2. Gas Composition Analysis

2.4.3. Product Analysis

Biomass Determination

Protein Content Analysis

Measurement and Composition Analysis of Extracellular Polysaccharide (EPS) Components

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Isolation and Screening of HOB for SCP Production

3.2. Physiological and Phylogenetic Characterizations of Strain ZZH C-3

3.3. Genome Analysis of Strain ZZH C-3

3.4. Optimization of Cultivation Conditions

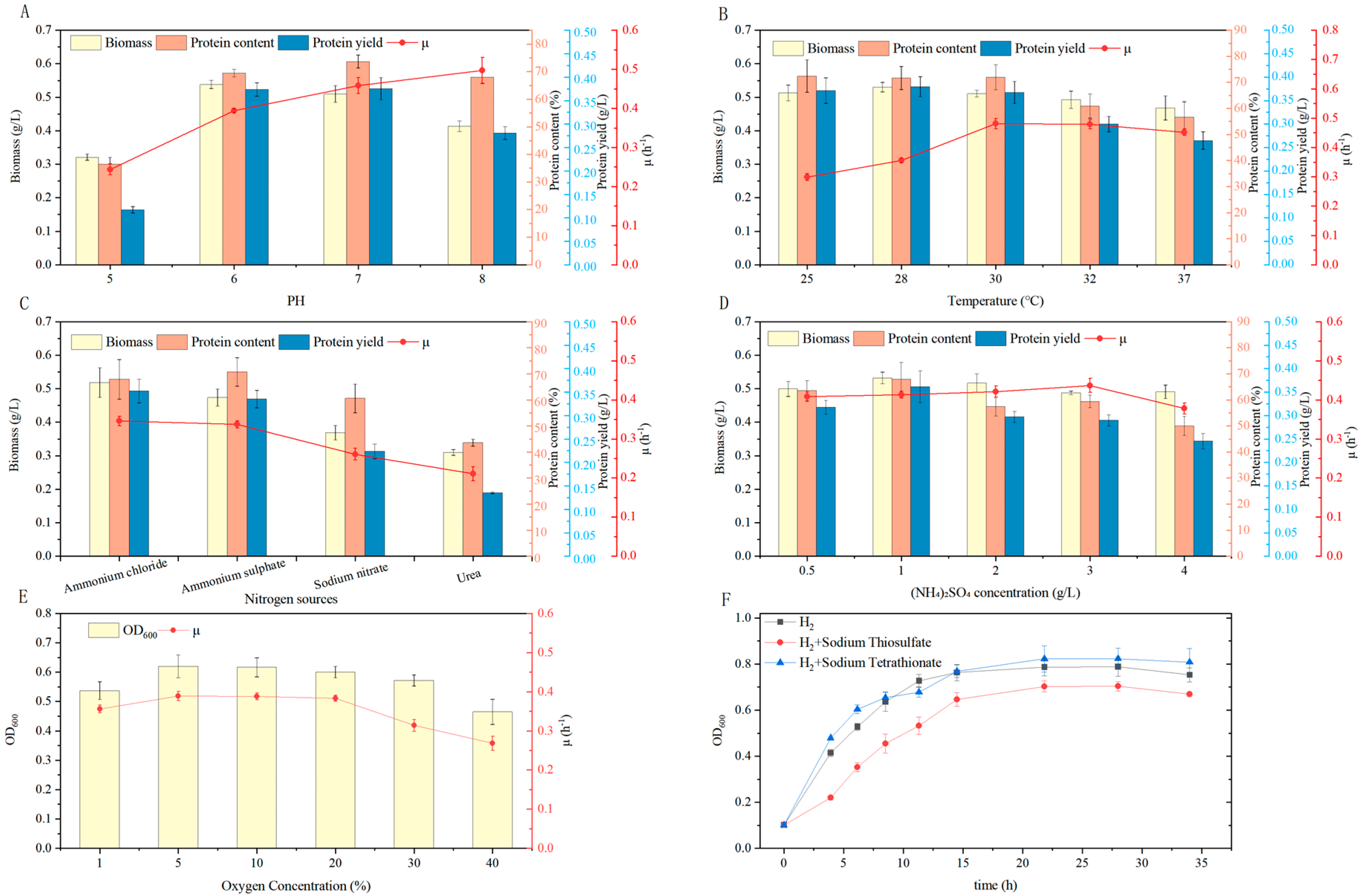

3.4.1. Optimization of Initial pH and Temperature

3.4.2. Optimization of Nitrogen Source

3.4.3. Optimization of Oxygen Concentration

3.4.4. Effect of Auxiliary Energy Sources

3.4.5. Optimization of the Medium Composition by RSM

PB Design for Screening Significant Factors

Steepest Ascent Experiment to Approach the Optimal Response Region

Optimization Results by RSM

Model Validation and Optimization Outcomes

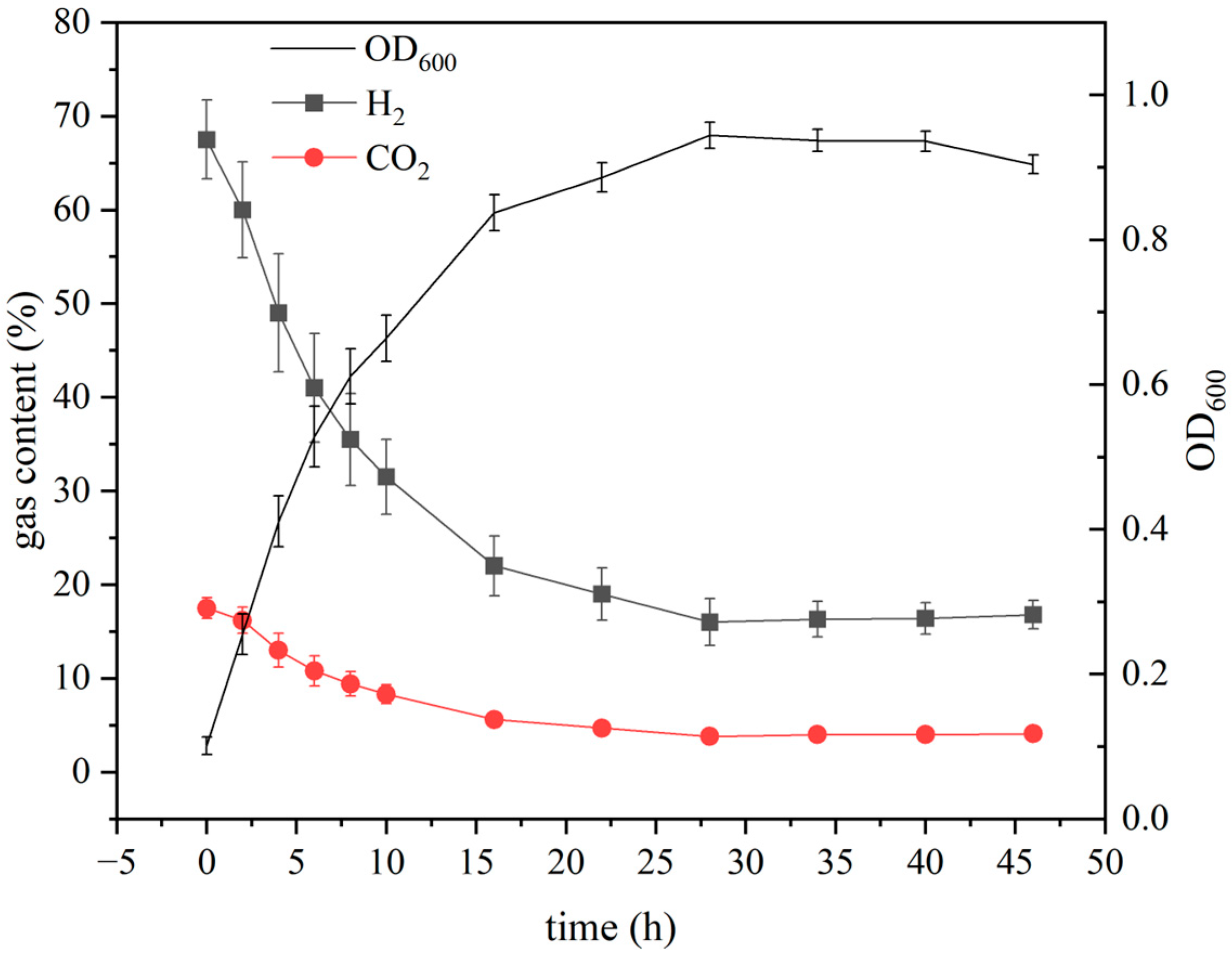

3.5. Growth Characteristics of ZZH C-3 Under Optimized Conditions

3.6. Elemental Analysis and EPS Characterization of ZZH C-3

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bernal-Cabas, M.; Kumar, K.; Terpstra, O.; van den Bogaard, S.; Ammar, A.B.; Makinen, S.; Herwig, L.; de Almeida, M.; Tervasmaki, P.; Blank, L.M.; et al. Food production from air: Gas precision fermentation with hydrogen-oxidising bacteria. Trends Biotechnol. 2025; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, M.J.; Rae, A.N.; Vereijken, J.M.; Meuwissen, M.P.M.; Fischer, A.R.H.; van Boekel, M.; Rutherfurd, S.M.; Gruppen, H.; Moughan, P.J.; Hendriks, W.H. The future supply of animal-derived protein for human consumption. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 29, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean, A.B.; Brown, R.C. Techno-Economic Analysis of Gas Fermentation for the Production of Single Cell Protein. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 3823–3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humpenöder, F.; Popp, A.; Schleussner, C.F.; Orlov, A.; Windisch, M.G.; Menke, I.; Pongratz, J.; Havermann, F.; Thiery, W.; Luo, F.; et al. Overcoming global inequality is critical for land-based mitigation in line with the Paris Agreement. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajic, B.; Vucurovic, D.; Vasic, D.; Jevtic-Mucibabic, R.; Dodic, S. Biotechnological Production of Sustainable Microbial Proteins from Agro-Industrial Residues and By-Products. Foods 2023, 12, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.; Chen, W.X.; Hong, R.R.; Chai, M.D.; Sun, Y.X.; Wang, Q.H.; Li, D.M. Efficient Mycoprotein Production with Low CO2 Emissions through Metabolic Engineering and Fermentation Optimization of Fusarium venenatum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 72, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, L.M.; Xu, J.; Ma, S.F.; Liang, X.F.; Wei, Z.X.; Li, D.M.; Xue, M. C1 gas protein: A potential protein substitute for advancing aquaculture sustainability. Rev. Aquac. 2023, 15, 1179–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Ma, C.L.; Wei, Z.X.; Zhai, Y.D.; Tian, N.; Zhu, Z.G.; Xue, M.; Li, D.M. Embracing a low-carbon future by the production and marketing of C1 gas protein. Biotechnol. Adv. 2023, 63, 108096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Huang, H.N.; Zhang, X.; Dong, L.; Chen, Y.G. Hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria and their applications in resource recovery and pollutant removal. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 835, 155559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matassa, S.; Boon, N.; Pikaar, I.; Verstraete, W. Microbial protein: Future sustainable food supply route with low environmental footprint. Microb. Biotechnol. 2016, 9, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenz, S.; Baumann, P.T.; Rückert, C.; Nebel, B.A.; Siebert, D.; Schwentner, A.; Eikmanns, B.J.; Hauer, B.; Kalinowski, J.; Takors, R.; et al. Exploiting Hydrogenophaga pseudoflava for aerobic syngas-based production of chemicals. Metab. Eng. 2019, 55, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Cui, L.; Ding, L.J.; Su, X.Y.; Luo, H.Y.; Huang, H.Q.; Wang, Y.; Yao, B.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.L. Unlocking the potential of Cupriavidus necator H16 as a platform for bioproducts production from carbon dioxide. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, A.; Patón, M.; Rodríguez, J. Bioenergetic trade-offs can reveal the path to superior microbial CO2 fixation pathways. mSystems 2025, 10, e0127424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcellin, E.; Angenent, L.T.; Nielsen, L.K.; Molitor, B. Recycling carbon for sustainable protein production using gas fermentation. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2022, 76, 102723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyyssölä, A.; Suhonen, A.; Ritala, A.; Oksman-Caldentey, K.-M. The role of single cell protein in cellular agriculture. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2022, 75, 102686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.S.; Jiang, L.J.; Zhao, Z.M.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Alain, K.; Cui, L.; Zhong, Y.S.; Peng, Y.Y.; Lai, Q.L.; et al. Chemolithoautotrophic diazotrophs dominate dark nitrogen fixation in mangrove sediments. ISME J. 2024, 18, wrae119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.D.; Wang, S.S.; Lai, Q.L.; Wei, S.P.; Jiang, L.J.; Shao, Z.Z. Sulfurimonas marina sp. nov., an obligately chemolithoautotrophic, sulphur-oxidizing bacterium isolated from a deep-sea sediment sample from the South China Sea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2022, 72, 005582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manirakiza, P.; Covaci, A.; Schepens, P. Comparative study on total lipid determination using Soxhlet, Roese-Gottlieb, Bligh & Dyer, and modified Bligh & Dyer extraction methods. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2001, 14, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Hao, X.; Li, D.; Zhu, X.; Huang, J.; Lai, Q.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Shao, Z. Aquibium pacificus sp. nov., a Novel Mixotrophic Bacterium from Bathypelagic Seawater in the Western Pacific Ocean. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Tamura, K.; Nei, M. MEGA-Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Software for Microcomputers. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1994, 10, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The Neighbor-Joining Method—A New Method for Reconstructing Phylogenetic Trees. Jpn. J. Genet. 1986, 61, 611. [Google Scholar]

- Strimmer, K.; vonHaeseler, A. Quartet puzzling: A quartet maximum-likelihood method for reconstructing tree topologies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1996, 13, 964–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zheng, Y.; Peng, X.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, C.; Xiao, X.; Wang, F. Vertical distribution and diversity of sulfate-reducing prokaryotes in the Pearl River estuarine sediments, Southern China. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2009, 70, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatusova, T.; DiCuccio, M.; Badretdin, A.; Chetvernin, V.; Nawrocki, E.P.; Zaslavsky, L.; Lomsadze, A.; Pruitt, K.D.; Borodovsky, M.; Ostell, J. NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 6614–6624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overbeek, R.; Olson, R.; Pusch, G.D.; Olsen, G.J.; Davis, J.J.; Disz, T.; Edwards, R.A.; Gerdes, S.; Parrello, B.; Shukla, M.; et al. The SEED and the Rapid Annotation of microbial genomes using Subsystems Technology (RAST). Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D206–D214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.H.; Ha, S.M.; Lim, J.; Kwon, S.; Chun, J. A large-scale evaluation of algorithms to calculate average nucleotide identity. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2017, 110, 1281–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta, K.R.; Gavril, D.; Karaiskakis, G. A new gas chromatographic methodology for the estimation of the composition of binary gas mixtures. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2003, 41, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.K.; Li, J.G.; Yan, W.L.; Zhao, W.Y.; Ye, C.S.; Yu, X. Biofilm formation and antioxidation were responsible for the increased resistance of N. eutropha to chloramination for drinking water treatment. Water Res. 2024, 254, 121432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuschmierz, L.; Meyer, M.; Bräsen, C.; Wingender, J.; Schmitz, O.J.; Siebers, B. Exopolysaccharide composition and size in Sulfolobus acidocaldarius biofilms. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 982745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Oh, H.S.; Park, S.C.; Chun, J. Towards a taxonomic coherence between average nucleotide identity and 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity for species demarcation of prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Zhong, Y.; Li, Y.; Sievert, S.M.; Huang, Z.; Wang, W.; Rubin-Blum, M.; Cao, X.; Wang, Y.; Shao, Z.; et al. Cultivation and metabolic versatility of novel and ubiquitous chemolithoautotrophic Campylobacteria from mangrove sediments. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e0036725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Auch, A.F.; Klenk, H.P.; Göker, M. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, M.; Ikeda, T.; Arai, H.; Ishii, M.; Igarashi, Y. Carboxylation reaction catalyzed by 2-oxoglutarate:ferredoxin oxidoreductases from Hydrogenobacter thermophilus. Extremophiles 2010, 14, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molari, M.; Hassenrueck, C.; Laso-Pérez, R.; Wegener, G.; Offre, P.; Scilipoti, S.; Boetius, A. A hydrogenotrophic Sulfurimonas is globally abundant in deep-sea oxygen-saturated hydrothermal plumes. Nat. Microbiol. 2023, 8, 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.S.; Jiang, L.J.; Hu, Q.T.; Cui, L.; Zhu, B.T.; Fu, X.T.; Lai, Q.L.; Shao, Z.Z.; Yang, S.P. Characterization of Sulfurimonas hydrogeniphila sp. nov., a Novel Bacterium Predominant in Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Vents and Comparative Genomic Analyses of the Genus Sulfurimonas. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 626705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, J.M.; Zielinski, F.U.; Pape, T.; Seifert, R.; Moraru, C.; Amann, R.; Hourdez, S.; Girguis, P.R.; Wankel, S.D.; Barbe, V.; et al. Hydrogen is an energy source for hydrothermal vent symbioses. Nature 2011, 476, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meuer, J.; Kuettner, H.C.; Zhang, J.K.; Hedderich, R.; Metcalf, W.W. Genetic analysis of the archaeon Methanosarcina barkeri Fusaro reveals a central role for Ech hydrogenase and ferredoxin in methanogenesis and carbon fixation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 5632–5637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adnan, A.I.; Ong, M.Y.; Nomanbhay, S.; Show, P.L. Determination of Dissolved CO2 Concentration in Culture Media: Evaluation of pH Value and Mathematical Data. Processes 2020, 8, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakarika, M.; Candry, P.; Depoortere, M.; Ganigué, R.; Rabaey, K. Impact of substrate and growth conditions on microbial protein production and composition. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 317, 124021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chialvo, A.A. On the solubility of gases in dilute solutions: Organic food for thoughts from a molecular thermodynamic perspective. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2018, 472, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S.; Giacinti, G.; Raynaud, C.D.; Cameleyre, X.; Alfenore, S.; Guillouet, S.; Gorret, N. Impact of the environmental parameters on single cell protein production and composition by Cupriavidus necator. J. Biotechnol. 2024, 388, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzo, R.; Papirio, S.; d’Antonio, L.; Esposito, G.; Matassa, S. Novel photo-chemoautotrophic system combining microalgae and hydrogen oxidizing bacteria for microbial protein production from carbon dioxide. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 434, 132792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishihara, H.; Igarashi, Y.; Kodama, T. Growth-characteristics and high cell-density cultivation of a marine obligately chemolithoautotrophic hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium Hydrogenovibrio-marinus strain MH-110 under a continuous gas-flow system. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 1991, 72, 358–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J.W.; Schut, G.J.; Boyd, E.S.; Mulder, D.W.; Shepard, E.M.; Broderick, J.B.; King, P.W.; Adams, M.W.W. [FeFe]- and [NiFe]-hydrogenase diversity, mechanism, and maturation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Mol. Cell Res. 2015, 1853, 1350–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groisman, E.A.; Hollands, K.; Kriner, M.A.; Lee, E.J.; Park, S.Y.; Pontes, M.H. Bacterial Mg2+ Homeostasis, Transport, and Virulence. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2013, 47, 625–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.Y.; Yang, Z.Y.; Zhou, L.; Papadakis, V.G.; Goula, M.A.; Liu, G.Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W. Calcium ion can alleviate ammonia inhibition on anaerobic digestion via balanced-strengthening dehydrogenases and reinforcing protein-binding structure: Model evaluation and microbial characterization. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 354, 127165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, G.; Kumar, V.; Arora, A.; Tomar, A.; Ashish; Sur, R.; Dutta, D. Affected energy metabolism under manganese stress governs cellular toxicity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yu, J. Comparison analysis on the energy efficiencies and biomass yields in microbial CO2 fixation. Process Biochem. 2017, 62, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, S.T.; Yilmaz, S.; Bar-Even, A.; Claassens, N.J.; Bordanaba-Florit, G.; Cotton, C.A.R.; Maria, A.; Finger-Bou, M.; Friedeheim, L.; Giner-Laguarda, N.; et al. Replacing the Calvin cycle with the reductive glycine pathway in Cupriavidus necator. Metab. Eng. 2020, 62, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fatty Acids (mol%) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C10:0 | 0.14 | - | - | 0.47 | - |

| C12:0 | 1.25 | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.58 | 0.4 |

| Summed feature 2 | 0.29 | - | - | 0.53 | 1.02 |

| 13:0 iso 3OH | 0.13 | - | - | 0.95 | 0.52 |

| C14:0 | 12.53 | 10.43 | 12.77 | 10.94 | 10.83 |

| C14:0 3-OH | 4.77 | 3.71 | 5.48 | 3.62 | 3.3 |

| Summed feature 3 (C16:1 ω7c/C16:1 ω6c) | 33.55 | 36.9 | 40.8 | 32.92 | 33.09 |

| C16:1 ω5c | 0.38 | 0.57 | 0.72 | 0.22 | 0.2 |

| C16:0 | 18.44 | 27.72 | 21.79 | 27.74 | 28.36 |

| C18:0 | 0.38 | 0.23 | 1.28 | 1.58 | 0.42 |

| Summed feature 8 (C18:1 ω7c/C18:1 ω6c) | 13.98 | 19.23 | 15.31 | 16.67 | 20.84 |

| C18:1ω5c | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.24 | - |

| C18:1ω9c | 0.22 | - | 0.23 | - | 0.36 |

| Pathway | Enzyme | Short Name | ZZH C-3 | HSL1–2 | HSL-1656 | HSL-3221 | HSL1–6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rTCA cycle | ATP-dependent citrate lyase (ACL) | AclA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| AclB | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Oxoglutarate:ferredoxin oxireductase (OOR) | OorA | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| OorB | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||

| OorC | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| OorD | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| OorE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Pyruvate:ferredoxin oxireductase (POR) | PorA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| PorB | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| PorC | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| PorD | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| PorE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Source | df | Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 9 | 0.0149 | 0.0017 | 84.08 | <0.0001 | significant |

| A-FeSO4·7H2O | 1 | 0.0027 | 0.0027 | 135.2 | <0.0001 | |

| B-CaCl2·2H2O | 1 | 0.0016 | 0.0016 | 80.99 | <0.0001 | |

| C-MnSO4·H2O | 1 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 3.36 | 0.1097 | |

| AB | 1 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 11.42 | 0.0118 | |

| AC | 1 | 0.0005 | 0.0005 | 26.84 | 0.0013 | |

| BC | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.6216 | 0.4563 | |

| A2 | 1 | 0.0054 | 0.0054 | 271.92 | <0.0001 | |

| B2 | 1 | 0.0011 | 0.0011 | 57.64 | 0.0001 | |

| C2 | 1 | 0.0024 | 0.0024 | 122.3 | <0.0001 | |

| Residual | 7 | 0.0001 | 0 | - | - | |

| Lack of Fit | 3 | 0.0001 | 0 | 3.13 | 0.1495 | not significant |

| Pure Error | 4 | 0 | 0 | - | - | |

| Cor Total | 16 | 0.0151 | - | - | - | |

| R2 = 99.08% | Adj R2 = 97.9% |

| Parameter | Unit | ZZH C-3 | Cupriavidus necator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Biomass Concentration | g DCW/L | 0.60 | ~1.448 |

| Protein Content | % DCW | 73.56 | 60~73 |

| Maximum Specific Growth Rate | h−1 | ~0.46 | ~0.3 |

| H2/CO2 Molar Consumption Ratio | mol H2/mol CO2 | 3.78 | 6.0~8.2 |

| Energy Conversion Efficiency (η H2-bio) | % | 42.5 | 12~18 |

| Biomass Yield on H2 (YH2) | g DCW/g H2 | 3.01 | 1.1–1.4 |

| Biomass Yield on CO2 (YCO2) | g DCW/g CO2 | 0.52 | 0.5~0.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cao, X.; Cui, L.; Sun, S.; Li, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Hong, R.; Xu, P.; Gao, X.; Jiang, L.; et al. Isolation and Screening of Hydrogen-Oxidizing Bacteria from Mangrove Sediments for Efficient Single-Cell Protein Production Using CO2. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020346

Cao X, Cui L, Sun S, Li T, Wang Y, Wang S, Hong R, Xu P, Gao X, Jiang L, et al. Isolation and Screening of Hydrogen-Oxidizing Bacteria from Mangrove Sediments for Efficient Single-Cell Protein Production Using CO2. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(2):346. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020346

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Xiaxing, Liang Cui, Shuai Sun, Tingzhao Li, Yong Wang, Shasha Wang, Rongfeng Hong, Pufan Xu, Xuewen Gao, Lijing Jiang, and et al. 2026. "Isolation and Screening of Hydrogen-Oxidizing Bacteria from Mangrove Sediments for Efficient Single-Cell Protein Production Using CO2" Microorganisms 14, no. 2: 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020346

APA StyleCao, X., Cui, L., Sun, S., Li, T., Wang, Y., Wang, S., Hong, R., Xu, P., Gao, X., Jiang, L., & Shao, Z. (2026). Isolation and Screening of Hydrogen-Oxidizing Bacteria from Mangrove Sediments for Efficient Single-Cell Protein Production Using CO2. Microorganisms, 14(2), 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020346