Sequencing and Analysis of Chicken Segmented Filamentous Bacteria Genome Revealed Unique Avian-Specific Features

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Primary Collection of SFB from Conventional Layer Hen and Broiler Chickens

2.3. Confirmation of SFB in Ilea Scrapings via PCR

2.4. Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization (FISH) and Gram-Stain Identification of SFB

2.5. Nanopore and Illumina Sequencing

2.6. Assembly of LSL-SFB Genome

2.7. HiC-Based Scaffolding

2.8. Comparative Pangenomic Analysis

2.9. Metabolic Analysis of LSL-SFB Genome and Comparisons to SFB from Other Host Species

2.10. Amplification and Cloning of LSL-SFB fliC

2.11. Phylogenetic Relationship of Chicken SFB fliC-2

2.12. Generation of Chicken SFB Three-Dimensional Models and Interactions with Chicken TLR-5

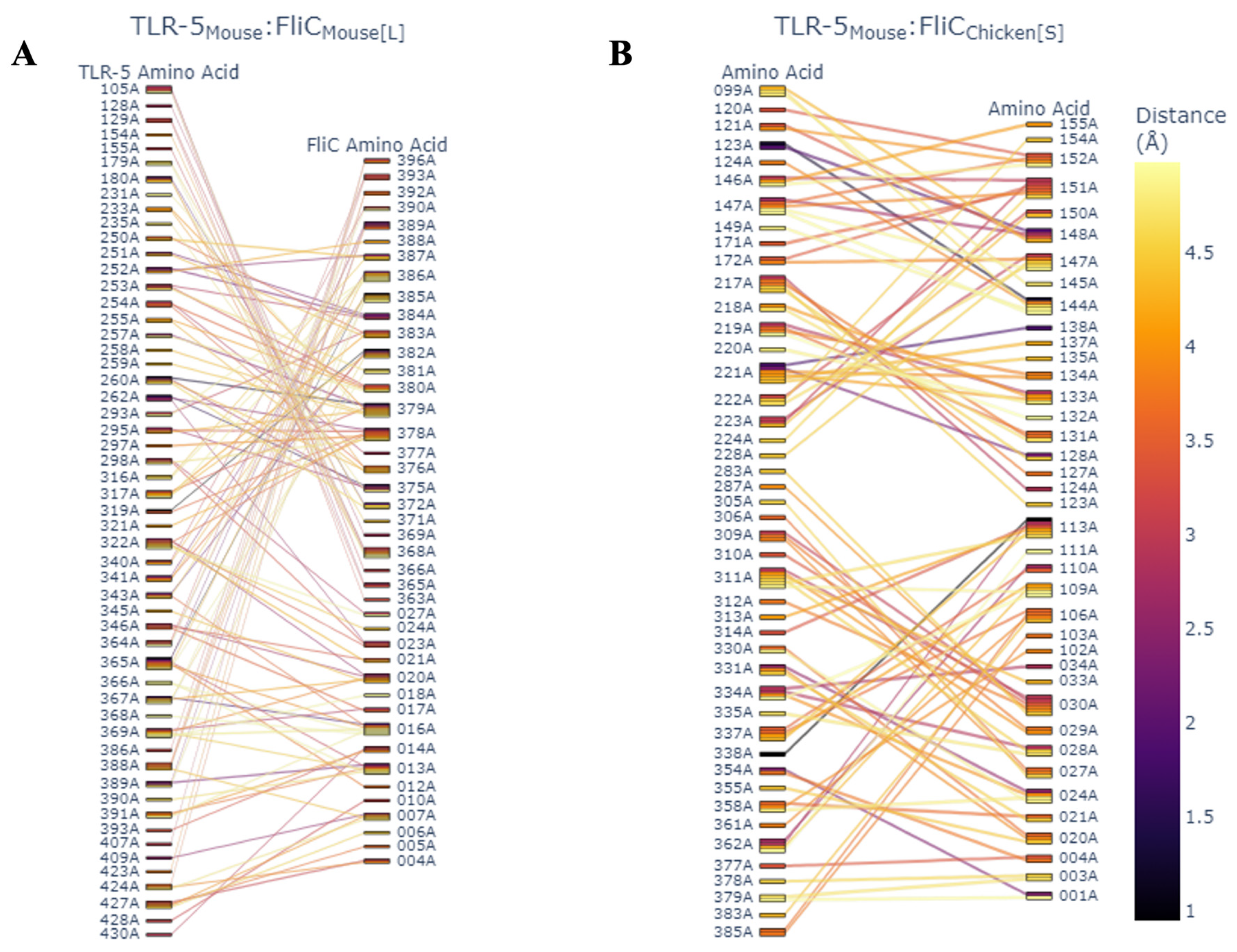

2.13. Predicted Cross-Species Interaction of LSL-SFB, Mouse SFB, and Host TLR-5s

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Detection and Collection of Avian-Specific SFB from Different Chicken Genetic Lines

3.2. Generation and Assembly of the First Chicken SFB Genome

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of scaffolds | 41 |

| Total size (bp) | 1,612,002 |

| Longest scaffold (bp) | 138,357 |

| Shortest scaffold (bp) | 905 |

| Mean scaffold size (bp) | 39,317 |

| Median scaffold size (bp) | 29,165 |

| N50 value (bp) | 68,453 |

| GC content (%) | ~25 |

| Metric | Before Hi-C Assembly | After Hi-C Assembly |

|---|---|---|

| Contigs | 41 | 1 |

| Bases | 1,612,002 | 1,631,855 |

| CDS | 1502 | 1529 |

| rRNA | 1 | 2 |

| tRNA | 33 | 35 |

| tmRNA | 1 | 1 |

| Metric | LSL-SFB Genome | Turkey SFB Genome |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Contigs | 1 | 41 |

| Total size (bp) | 1,631,855 | 1,631,326 |

| Number of Coding sequences (CDS) | 1529 | 1570 |

| rRNA genes | 2 | 1 |

| tRNA genes | 35 | 33 |

| tmRNA genes | 1 | 1 |

3.3. Pangenomic Analysis of SFB

3.4. Metabolic Analysis of LSL-SFB Compared to SFB from Other Hosts

3.5. Structural and Phylogenetic Analysis of LSL-SFB FliC from Different Chicken Genetic Lines

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SFB | Segmented filamentous bacteria |

| LSL | Lohmann Select Layer |

| TLR | Toll-like Receptor |

| FliC | Flagellin subunit C |

References

- Schnupf, P.; Gaboriau-Routhiau, V.; Gros, M.; Friedman, R.; Moya-Nilges, M.; Nigro, G.; Cerf-Bensussan, N.; Sansonetti, P.J. Growth and host interaction of mouse segmented filamentous bacteria in vitro. Nature 2015, 520, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ivanov, I.I.; Atarashi, K.; Manel, N.; Brodie, E.L.; Shima, T.; Karaoz, U.; Wei, D.; Goldfarb, K.C.; Santee, C.A.; Lynch, S.V.; et al. Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell 2009, 139, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Farkas, A.M.; Panea, C.; Goto, Y.; Nakato, G.; Galan-Diez, M.; Narushima, S.; Honda, K.; Ivanov, I.I. Induction of Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria in the murine intestine. J. Immunol. Methods 2015, 421, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Redweik, G.A.J.; Daniels, K.; Severin, A.J.; Lyte, M.; Mellata, M. Oral Treatments with Probiotics and Live Salmonella Vaccine Induce Unique Changes in Gut Neurochemicals and Microbiome in Chickens. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Meinen-Jochum, J.; Ott, L.C.; Mellata, M. Segmented filamentous bacteria-based treatment to elicit protection against Enterobacteriaceae in Layer chickens. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1231837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Meinen-Jochum, J.; Skow, C.J.; Mellata, M. Layer segmented filamentous bacteria colonize and impact gut health of broiler chickens. mSphere 2024, 9, e0049224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Liu, W.; Liao, N.; Jiang, M.; Zhu, B.; Yu, H.D.; Xiang, C.; Wang, X. Comparative analysis of the distribution of segmented filamentous bacteria in humans, mice and chickens. ISME J. 2013, 7, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hedblom, G.A.; Reiland, H.A.; Sylte, M.J.; Johnson, T.J.; Baumler, D.J. Segmented Filamentous Bacteria—Metabolism Meets Immunity. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ericsson, A.C.; Hagan, C.E.; Davis, D.J.; Franklin, C.L. Segmented filamentous bacteria: Commensal microbes with potential effects on research. Comp. Med. 2014, 64, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tannock, G.W.; Miller, J.R.; Savage, D.C. Host specificity of filamentous, segmented microorganisms adherent to the small bowel epithelium in mice and rats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1984, 47, 441–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pamp, S.J.; Harrington, E.D.; Quake, S.R.; Relman, D.A.; Blainey, P.C. Single-cell sequencing provides clues about the host interactions of segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB). Genome Res. 2012, 22, 1107–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Redweik, G.A.J.; Kogut, M.H.; Arsenault, R.J.; Mellata, M. Oral Treatment with Ileal Spores Triggers Immunometabolic Shifts in Chicken Gut. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schnupf, P.; Gaboriau-Routhiau, V.; Cerf-Bensussan, N. Host interactions with Segmented Filamentous Bacteria: An unusual trade-off that drives the post-natal maturation of the gut immune system. Semin. Immunol. 2013, 25, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, B.; Kim, E.-D.; Kim, B.-H.; Tomachi, T.; He, J.; Kelsall, B.L. Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) drives enhanced T cell-dependent IgA and IgG2b responses in Peyer’s patches. J. Immunol. 2023, 210, 218.10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talham, G.L.; Jiang, H.Q.; Bos, N.A.; Cebra, J.J. Segmented filamentous bacteria are potent stimuli of a physiologically normal state of the murine gut mucosal immune system. Infect. Immun. 1999, 67, 1992–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Suzuki, K.; Meek, B.; Doi, Y.; Muramatsu, M.; Chiba, T.; Honjo, T.; Fagarasan, S. Aberrant expansion of segmented filamentous bacteria in IgA-deficient gut. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 1981–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jonsson, H.; Hugerth, L.W.; Sundh, J.; Lundin, E.; Andersson, A.F. Genome sequence of segmented filamentous bacteria present in the human intestine. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hedblom, G.A.; Dev, K.; Bowden, S.D.; Baumler, D.J. Comparative genome analysis of commensal segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) from turkey and murine hosts reveals distinct metabolic features. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Contriciani, R.E.; Grade, C.V.C.; Buzzatto-Leite, I.; da Veiga, F.C.; Ledur, M.C.; Reverter, A.; Alexandre, P.A.; Cesar, A.S.M.; Coutinho, L.L.; Alvares, L.E. Phenotypic divergence between broiler and layer chicken lines is regulated at the molecular level during development. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Qanbari, S.; Rubin, C.J.; Maqbool, K.; Weigend, S.; Weigend, A.; Geibel, J.; Kerje, S.; Wurmser, C.; Peterson, A.T.; Brisbin, I.L.; et al. Genetics of adaptation in modern chicken. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1007989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Klaasen, H.L.; Koopman, J.P.; Van den Brink, M.E.; Van Wezel, H.P.; Beynen, A.C. Mono-association of mice with non-cultivable, intestinal, segmented, filamentous bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 1991, 156, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Moon, C.D.; Zheng, N.; Huws, S.; Zhao, S.; Wang, J. Opportunities and challenges of using metagenomic data to bring uncultured microbes into cultivation. Microbiome 2022, 10, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alain, K.; Querellou, J. Cultivating the uncultured: Limits, advances and future challenges. Extremophiles 2009, 13, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspi, R.; Billington, R.; Keseler, I.M.; Kothari, A.; Krummenacker, M.; Midford, P.E.; Ong, W.K.; Paley, S.; Subhraveti, P.; Karp, P.D. The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes—A 2019 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D445–D453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, Y.; Yin, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Xiang, C. Induction of Intestinal Th17 Cells by Flagellins from Segmented Filamentous Bacteria. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ladinsky, M.S.; Araujo, L.P.; Zhang, X.; Veltri, J.; Galan-Diez, M.; Soualhi, S.; Lee, C.; Irie, K.; Pinker, E.Y.; Narushima, S.; et al. Endocytosis of commensal antigens by intestinal epithelial cells regulates mucosal T cell homeostasis. Science 2019, 363, eaat4042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, N.; Yin, Y.; Sun, G.; Xiang, C.; Liu, D.; Yu, H.D.; Wang, X. Colonization and distribution of segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) in chicken gastrointestinal tract and their relationship with host immunity. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2012, 81, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1303.3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R.; Subgroup, G.P.D.P. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Durand, N.C.; Shamim, M.S.; Machol, I.; Rao, S.S.; Huntley, M.H.; Lander, E.S.; Aiden, E.L. Juicer Provides a One-Click System for Analyzing Loop-Resolution Hi-C Experiments. Cell Syst. 2016, 3, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bowers, R.M.; Kyrpides, N.C.; Stepanauskas, R.; Harmon-Smith, M.; Doud, D.; Reddy, T.B.K.; Schulz, F.; Jarett, J.; Rivers, A.R.; Eloe-Fadrosh, E.A.; et al. Minimum information about a single amplified genome (MISAG) and a metagenome-assembled genome (MIMAG) of bacteria and archaea. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 725–731, Erratum in Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Karp, P.D.; Midford, P.E.; Billington, R.; Kothari, A.; Krummenacker, M.; Latendresse, M.; Ong, W.K.; Subhraveti, P.; Caspi, R.; Fulcher, C.; et al. Pathway Tools version 23.0 update: Software for pathway/genome informatics and systems biology. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tamura, K.; Nei, M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1993, 10, 512–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.T.; Taylor, W.R.; Thornton, J.M. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1992, 8, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Meng, E.C.; Couch, G.S.; Croll, T.I.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci. 2021, 30, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Meng, E.C.; Goddard, T.D.; Pettersen, E.F.; Couch, G.S.; Pearson, Z.J.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Tools for structure building and analysis. Protein Sci. 2023, 32, e4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- UniProt Consortium. UniProt: The Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D523–D531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sebastiani, G.; Leveque, G.; Larivière, L.; Laroche, L.; Skamene, E.; Gros, P.; Malo, D. Cloning and characterization of the murine toll-like receptor 5 (Tlr5) gene: Sequence and mRNA expression studies in Salmonella-susceptible MOLF/Ei mice. Genomics 2000, 64, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Tao, H.; He, J.; Huang, S.Y. The HDOCK server for integrated protein-protein docking. Nat. Protoc. 2020, 15, 1829–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cock, P.J.; Antao, T.; Chang, J.T.; Chapman, B.A.; Cox, C.J.; Dalke, A.; Friedberg, I.; Hamelryck, T.; Kauff, F.; Wilczynski, B.; et al. Biopython: Freely available Python tools for computational molecular biology and bioinformatics. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1422–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, H.; Yin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Xiang, C. Host Specificity of Flagellins from Segmented Filamentous Bacteria Affects Their Patterns of Interaction with Mouse Ileal Mucosal Proteins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, M.; Shi, S.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, F.; Xiao, Y.; Li, X.; Pan, X.; Feng, Y.; Liu, D.; Guo, Y.; et al. Synthetic microbial community improves chicken intestinal homeostasis and provokes anti-Salmonella immunity mediated by segmented filamentous bacteria. ISME J. 2025, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sczesnak, A.; Segata, N.; Qin, X.; Gevers, D.; Petrosino, J.F.; Huttenhower, C.; Littman, D.R.; Ivanov, I.I. The genome of th17 cell-inducing segmented filamentous bacteria reveals extensive auxotrophy and adaptations to the intestinal environment. Cell Host Microbe 2011, 10, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Larabi, A.B.; Masson, H.L.P.; Bäumler, A.J. Bile acids as modulators of gut microbiota composition and function. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2172671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ramírez-Pérez, O.; Cruz-Ramón, V.; Chinchilla-López, P.; Méndez-Sánchez, N. The Role of the Gut Microbiota in Bile Acid Metabolism. Ann. Hepatol. 2017, 16, s21–s26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridlon, J.M.; Harris, S.C.; Bhowmik, S.; Kang, D.J.; Hylemon, P.B. Consequences of bile salt biotransformations by intestinal bacteria. Gut Microbes 2016, 7, 22–39, Erratum in Gut Microbes 2016, 7, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Malard, F.; Dore, J.; Gaugler, B.; Mohty, M. Introduction to host microbiome symbiosis in health and disease. Mucosal Immunol. 2021, 14, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stewart, E.J. Growing unculturable bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 4151–4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Beurel, E. Stress in the microbiome-immune crosstalk. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2327409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, J.J.; Zhu, S.; Tang, Y.F.; Gu, F.; Liu, J.X.; Sun, H.Z. Microbiota-host crosstalk in the newborn and adult rumen at single-cell resolution. BMC Biol. 2022, 20, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liao, X.; Shao, Y.; Sun, G.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Guo, Y.; Luo, X.; Lu, L. The relationship among gut microbiota, short-chain fatty acids, and intestinal morphology of growing and healthy broilers. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 5883–5895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Parada Venegas, D.; De la Fuente, M.K.; Landskron, G.; González, M.J.; Quera, R.; Dijkstra, G.; Harmsen, H.J.M.; Faber, K.N.; Hermoso, M.A. Short Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)-Mediated Gut Epithelial and Immune Regulation and Its Relevance for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 277, Erratum in Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khatibjoo, A.; Kermanshahi, H.; Golian, A.; Zaghari, M. The effect of n-6/n-3 fatty acid ratios on broiler breeder performance, hatchability, fatty acid profile and reproduction. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2018, 102, 986–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.; Hou, L.; Yang, Y. The Development of the Gut Microbiota and Short-Chain Fatty Acids of Layer Chickens in Different Growth Periods. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 666535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ali, Q.; Ma, S.; La, S.; Guo, Z.; Liu, B.; Gao, Z.; Farooq, U.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Cui, Y.; et al. Microbial short-chain fatty acids: A bridge between dietary fibers and poultry gut health—A review. Anim. Biosci. 2022, 35, 1461–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Forte, C.; Manuali, E.; Abbate, Y.; Papa, P.; Vieceli, L.; Tentellini, M.; Trabalza-Marinucci, M.; Moscati, L. Dietary Lactobacillus acidophilus positively influences growth performance, gut morphology, and gut microbiology in rurally reared chickens. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 930–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rastogi, S.; Singh, A. Gut microbiome and human health: Exploring how the probiotic genus Lactobacillus modulate immune responses. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1042189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, X.Z.; Wen, Z.G.; Hua, J.L. Effects of dietary inclusion of Lactobacillus and inulin on growth performance, gut microbiota, nutrient utilization, and immune parameters in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 4656–4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judkins, T.C.; Archer, D.L.; Kramer, D.C.; Solch, R.J. Probiotics, Nutrition, and the Small Intestine. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2020, 22, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Chen, D.; Yu, B.; He, J.; Yu, J.; Mao, X.; Huang, Z.; Luo, Y.; Luo, J.; Zheng, P. Lactic Acid and Glutamine Have Positive Synergistic Effects on Growth Performance, Intestinal Function, and Microflora of Weaning Piglets. Animals 2024, 14, 3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mathur, H.; Beresford, T.P.; Cotter, P.D. Health Benefits of Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) Fermentates. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yoon, S.I.; Kurnasov, O.; Natarajan, V.; Hong, M.; Gudkov, A.V.; Osterman, A.L.; Wilson, I.A. Structural basis of TLR5-flagellin recognition and signaling. Science 2012, 335, 859–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang, J.; Yan, H. TLR5: Beyond the recognition of flagellin. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2017, 14, 1017–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, E.; Yang, J.; Yang, Y.; Yu, J.; Xiao, Y.; Li, W.; Zhou, D.; Li, Y.; Zhao, B.; et al. Frontline Science: Nasal epithelial GM-CSF contributes to TLR5-mediated modulation of airway dendritic cells and subsequent IgA response. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2017, 102, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Ahmed, J.; Wang, G.; Hassan, I.; Strulovici-Barel, Y.; Salit, J.; Mezey, J.G.; Crystal, R.G. Airway epithelial expression of TLR5 is downregulated in healthy smokers and smokers with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Immunol. 2012, 189, 2217–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Akira, S.; Uematsu, S.; Takeuchi, O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 2006, 124, 783–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clasen, S.J.; Bell, M.E.W.; Borbón, A.; Lee, D.H.; Henseler, Z.M.; de la Cuesta-Zuluaga, J.; Parys, K.; Zou, J.; Wang, Y.; Altmannova, V.; et al. Silent recognition of flagellins from human gut commensal bacteria by Toll-like receptor 5. Sci. Immunol. 2023, 8, eabq7001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahoun, A.; Jensen, K.; Corripio-Miyar, Y.; McAteer, S.; Smith, D.G.E.; McNeilly, T.N.; Gally, D.L.; Glass, E.J. Host species adaptation of TLR5 signalling and flagellin recognition. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| LSL-fliC-1 | LSL-fliC-2 | Mouse-fliC | Rat-fliC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSL-fliC-1 | 75% | 82.09% | 81.84% | |

| LSL-fliC-2 | 75% | 81.75% | 81.60% | |

| Mouse-fliC | 82.09% | 81.75% | 99.93% | |

| Rat-fliC | 81.84% | 81.60% | 99.83% | |

| Accession Number | Mellata_01007 | Mellata_01003 | KX659017.1 | AP012210.1 |

| Genetic Line | Nucleotide Identity (%) | Amino Acid Identity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Lohmann Selected Leghorn | 537/537 (100) | 179/179 (100) |

| Dekalb White Leghorn | 533/537 (99) | 177/179 (99) |

| Cobb 700 | 530/537 (99) | 175/179 (98) |

| Ross 308 | 520/537 (97) | 177/179 (99) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Meinen-Jochum, J.; Satheesh, V.; Masonbrink, R.E.; Rodriguez-Gallegos, J.; Wright, D.A.; Severin, A.J.; Mellata, M. Sequencing and Analysis of Chicken Segmented Filamentous Bacteria Genome Revealed Unique Avian-Specific Features. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020341

Meinen-Jochum J, Satheesh V, Masonbrink RE, Rodriguez-Gallegos J, Wright DA, Severin AJ, Mellata M. Sequencing and Analysis of Chicken Segmented Filamentous Bacteria Genome Revealed Unique Avian-Specific Features. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(2):341. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020341

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeinen-Jochum, Jared, Viswanathan Satheesh, Rick E. Masonbrink, Jonathan Rodriguez-Gallegos, David A. Wright, Andrew J. Severin, and Melha Mellata. 2026. "Sequencing and Analysis of Chicken Segmented Filamentous Bacteria Genome Revealed Unique Avian-Specific Features" Microorganisms 14, no. 2: 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020341

APA StyleMeinen-Jochum, J., Satheesh, V., Masonbrink, R. E., Rodriguez-Gallegos, J., Wright, D. A., Severin, A. J., & Mellata, M. (2026). Sequencing and Analysis of Chicken Segmented Filamentous Bacteria Genome Revealed Unique Avian-Specific Features. Microorganisms, 14(2), 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020341