The Gut Microbiota–Tryptophan–Brain Axis in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A New Frontier for Probiotic Intervention

Abstract

1. Overview of ASD

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategies

2.2. Inclusion Criteria and Exclusion Criteria

- (1)

- Children and adolescents under 20 years of age diagnosed with ASD, autistic disorder, or Asperger’s syndrome according to generally accepted diagnostic criteria;

- (2)

- Use of probiotics or probiotic preparations as the primary intervention in the experimental group;

- (3)

- No restrictions on control group interventions;

- (4)

- Measurement of autism-related behavioral symptoms using validated scales;

- (5)

- Study designs: randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and crossover trials.

- (1)

- Participants aged 18 years or older;

- (2)

- Full-text articles unavailable after contacting the authors.

- (1)

- Participants aged 18 years or older;

- (2)

- Full-text articles unavailable after contacting the authors;

- (3)

- Insufficient data for meta-analysis;

- (4)

- Lack of information on the specific probiotic strains used.

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

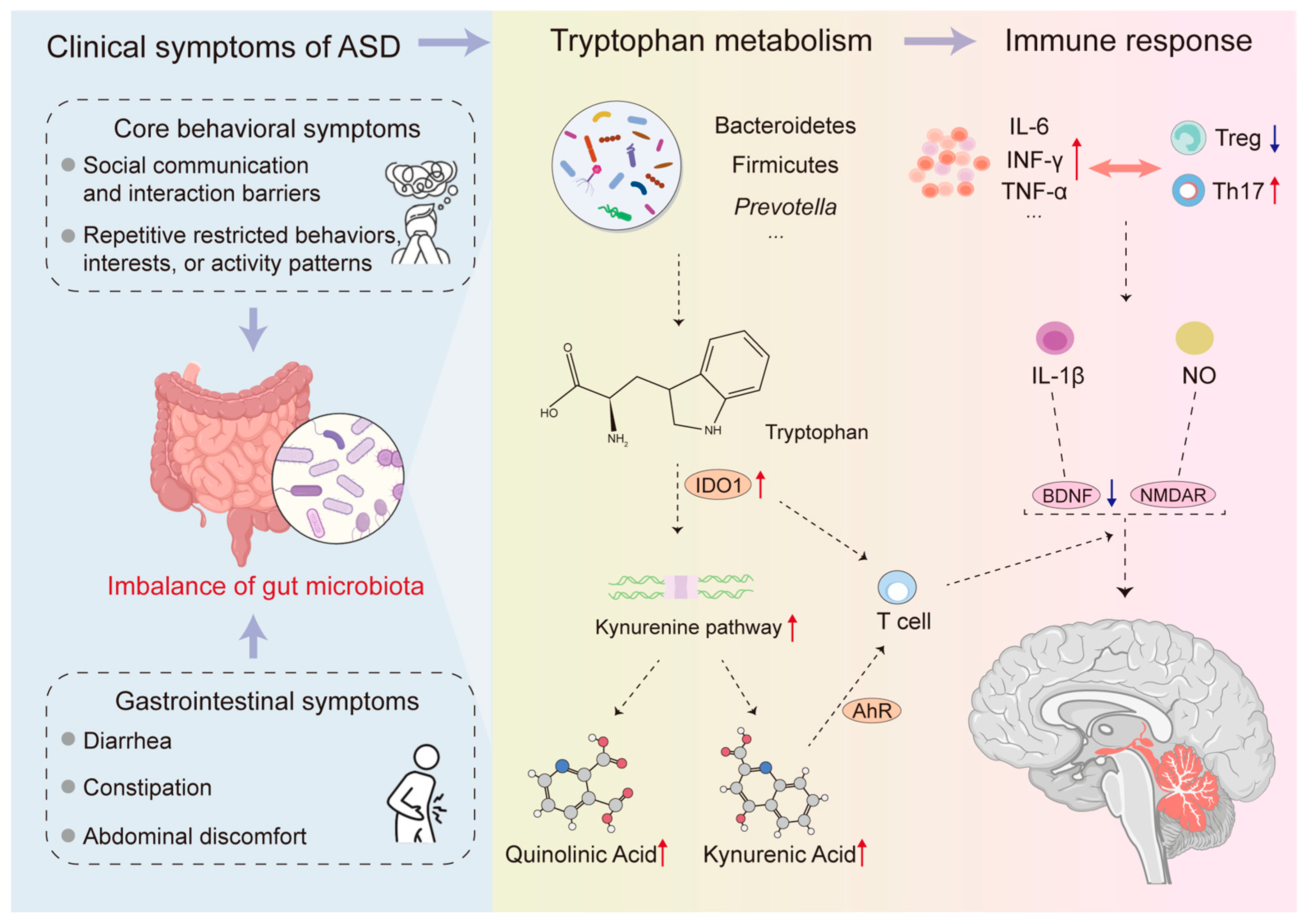

3. Gut Microbiome Characteristics and Accompanying Pathophysiological Changes in ASD Patients

4. Trp Metabolism: A Core Bridge Connecting Gut Microbiota and ASD

4.1. Trp Metabolism

4.2. The Link Between Trp Metabolism Imbalance and ASD

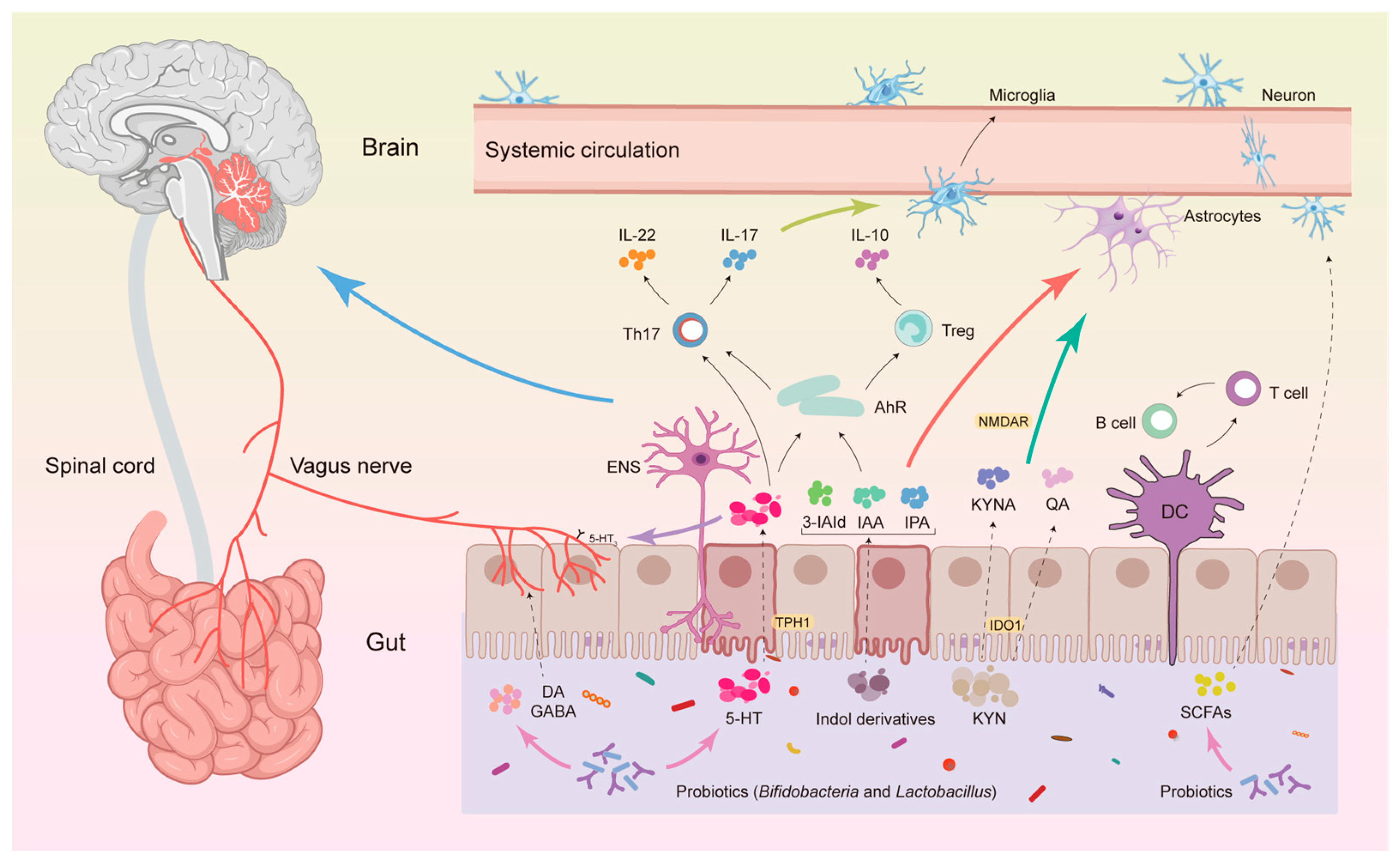

4.3. The Mechanism by Which Gut Microbiota Affects ASD Through Trp Metabolism

4.3.1. The KP Pathway

4.3.2. 5-HT Pathway

4.3.3. Indole and Its Metabolite Pathways

5. Probiotic Intervention: Targeting the Gut Microbiota–Trp Metabolic Axis

5.1. Probiotics Regulate Gut Microbiota

5.2. Probiotics Regulate Trp Metabolism

5.3. Evidence That Probiotics Mediate Trp Metabolism to Improve Symptoms of ASD

5.3.1. Overall Pattern

5.3.2. Trials with Improvement

5.3.3. Trials with Mixed or Null Results

5.3.4. Baseline and Responders

5.3.5. Sources of Heterogeneity

- (1)

- Outcome selection and measurement sensitivity: clinician-rated core measures (e.g., ADOS-based tools) may be less sensitive to short-term change than caregiver-rated questionnaires, while caregiver measures can be more susceptible to expectancy/placebo effects.

- (2)

- Baseline phenotype and stratification: ASD is heterogeneous; GI symptom burden, age/developmental stage, baseline severity, and dietary selectivity can influence response and should be pre-specified for subgroup analyses.

- (3)

- Strain/formulation specificity: single-strain vs. multi-strain products, synbiotics (probiotic + prebiotic), and product viability differ markedly, limiting cross-study comparability.

- (4)

- Dose–duration heterogeneity: trials vary by orders of magnitude in CFU/day and by intervention duration (weeks–months), precluding simple dose–response inference without harmonized reporting.

- (5)

- Concomitant interventions and diet: ongoing behavioral therapies, medications, dietary modifications, or adjunctive agents (e.g., oxytocin) can confound attribution of effects to probiotics alone.

- (6)

- Limited pathway-level measurement: many trials do not quantify Trp-pathway metabolites (e.g., Kyn/KA-related readouts), making it difficult to connect clinical outcomes to the Trp-centered mechanistic framework.

5.3.6. Dose–Response, Duration–Response, and Formulation Considerations

5.4. Clinical Positioning of Probiotics in ASD Management

6. Challenges and Future of Probiotic Intervention for ASD

6.1. Current Challenges

6.2. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fernandez, B.A.; Scherer, S.W. Syndromic Autism Spectrum Disorders: Moving from a Clinically Defined to a Molecularly Defined Approach. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2017, 19, 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt, G.; Uysal, G.; Düzkaya, D.S. Examination of Care Burden and Stress Coping Styles of Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2019, 47, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, J.P.; Du, J. Brief Report: Forecasting the Economic Burden of Autism in 2015 and 2025 in the United States. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2015, 45, 4135–4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkin, M.S.; Wolfe, B.L. Trends in Autism Prevalence in the U.S.: A Lagging Economic Indicator? J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 50, 1095–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, M.; Roth, G.A.; Aravkin, A.Y.; Zheng, P.; Abate, K.H.; Abate, Y.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasgholizadeh, R.; Abbasi, M.A.; Abbasian, M.; et al. Global Burden and Strength of Evidence for 88 Risk Factors in 204 Countries and 811 Subnational Locations, 1990–2021: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2162–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiteley, P.; Haracopos, D.; Knivsberg, A.-M.; Reichelt, K.L.; Parlar, S.; Jacobsen, J.; Seim, A.; Pedersen, L.; Schondel, M.; Shattock, P. The ScanBrit Randomised, Controlled, Single-Blind Study of a Gluten- and Casein-Free Dietary Intervention for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Nutr. Neurosci. 2010, 13, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, N.; Walker, M.M.; Talley, N.J. The Mucosal Immune System: Master Regulator of Bidirectional Gut–Brain Communications. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharon, G.; Sampson, T.R.; Geschwind, D.H.; Mazmanian, S.K. The Central Nervous System and the Gut Microbiome. Cell 2016, 167, 915–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz-Zadeh, L.; Ringold, S.M.; Jayashankar, A.; Kilroy, E.; Butera, C.; Jacobs, J.P.; Tanartkit, S.; Mahurkar-Joshi, S.; Bhatt, R.R.; Dapretto, M.; et al. Relationships between Brain Activity, Tryptophan-Related Gut Metabolites, and Autism Symptomatology. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strati, F.; Cavalieri, D.; Albanese, D.; De Felice, C.; Donati, C.; Hayek, J.; Jousson, O.; Leoncini, S.; Renzi, D.; Calabrò, A.; et al. New Evidences on the Altered Gut Microbiota in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Microbiome 2017, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Duan, G.; Song, C.; Li, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Gut Microbiota Changes in Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 129, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuomo, M.; Coretti, L.; Costabile, D.; Della Monica, R.; De Riso, G.; Buonaiuto, M.; Trio, F.; Bravaccio, C.; Visconti, R.; Berni Canani, R.; et al. Host Fecal DNA Specific Methylation Signatures Mark Gut Dysbiosis and Inflammation in Children Affected by Autism Spectrum Disorder. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, D.L.; Nascimbene, C.; Krishnan, C.; Zimmerman, A.W.; Pardo, C.A. Neuroglial Activation and Neuroinflammation in the Brain of Patients with Autism. Ann. Neurol. 2005, 57, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matta, S.M.; Hill-Yardin, E.L.; Crack, P.J. The Influence of Neuroinflammation in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Brain Behav. Immun. 2019, 79, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellul, P.; Rosenzwajg, M.; Peyre, H.; Fourcade, G.; Mariotti-Ferrandiz, E.; Trebossen, V.; Klatzmann, D.; Delorme, R. Regulatory T Lymphocytes/Th17 Lymphocytes Imbalance in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Evidence from a Meta-Analysis. Mol. Autism 2021, 12, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, A.; Ahmad, S.F.; Attia, S.M.; AL-Ayadhi, L.Y.; Al-Harbi, N.O.; Bakheet, S.A. Dysregulation in IL-6 Receptors Is Associated with Upregulated IL-17A Related Signaling in CD4+ T Cells of Children with Autism. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 97, 109783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Than, U.T.T.; Nguyen, L.T.; Nguyen, P.H.; Nguyen, X.-H.; Trinh, D.P.; Hoang, D.H.; Nguyen, P.A.T.; Dang, V.D. Inflammatory Mediators Drive Neuroinflammation in Autism Spectrum Disorder and Cerebral Palsy. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairisalo, M.; Korhonen, L.; Sepp, M.; Pruunsild, P.; Kukkonen, J.P.; Kivinen, J.; Timmusk, T.; Blomgren, K.; Lindholm, D. NF-κB-dependent Regulation of Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor in Hippocampal Neurons by X-linked Inhibitor of Apoptosis Protein. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2009, 30, 958–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Careaga, M.; Rogers, S.; Hansen, R.L.; Amaral, D.G.; Van de Water, J.; Ashwood, P. Immune Endophenotypes in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2017, 81, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solvay, M.; Holfelder, P.; Klaessens, S.; Pilotte, L.; Stroobant, V.; Lamy, J.; Naulaerts, S.; Spillier, Q.; Frédérick, R.; De Plaen, E.; et al. Tryptophan Depletion Sensitizes the AHR Pathway by Increasing AHR Expression and GCN2/LAT1-Mediated Kynurenine Uptake, and Potentiates Induction of Regulatory T Lymphocytes. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e006728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, E.; Sun, Z.; Fu, D.; Duan, G.; Jiang, M.; Yu, Y.; Mei, L.; Yang, P.; Tang, Y.; et al. Altered Gut Microbiota and Short Chain Fatty Acids in Chinese Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, M.; Piccolo, M.; Vannini, L.; Siragusa, S.; De Giacomo, A.; Serrazzanetti, D.I.; Cristofori, F.; Guerzoni, M.E.; Gobbetti, M.; Francavilla, R. Fecal Microbiota and Metabolome of Children with Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodd, D.; Spitzer, M.H.; Van Treuren, W.; Merrill, B.D.; Hryckowian, A.J.; Higginbottom, S.K.; Le, A.; Cowan, T.M.; Nolan, G.P.; Fischbach, M.A.; et al. A Gut Bacterial Pathway Metabolizes Aromatic Amino Acids into Nine Circulating Metabolites. Nature 2017, 551, 648–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meguid, N.; Ismail, S.R.; Anwar, M.; Hashish, A.; Semenova, Y.; Abdalla, E.; Taha, M.S.; Elsaeid, A.; Bjørklund, G. Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid and Glutamate System Dysregulation in a Small Population of Egyptian Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Metab. Brain Dis. 2025, 40, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Pan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Fang, X.; Liang, L.; Li, H.; Dong, Z.; Fan, S.; et al. Gut Microbial GABA Imbalance Emerges as a Metabolic Signature in Mild Autism Spectrum Disorder Linked to Overrepresented Escherichia. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 101919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameson, K.G.; Kazmi, S.A.; Ohara, T.E.; Son, C.; Yu, K.B.; Mazdeyasnan, D.; Leshan, E.; Vuong, H.E.; Paramo, J.; Lopez-Romero, A.; et al. Select Microbial Metabolites in the Small Intestinal Lumen Regulate Vagal Activity via Receptor-Mediated Signaling. iScience 2025, 28, 111699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, L.; Dai, Y.; Wei, H.; Jia, F.-Y.; Hao, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, J.; Wu, L.-J.; et al. Gender Specific Influence of Serotonin on Core Symptoms and Neurodevelopment of Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Multicenter Study in China. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2025, 19, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelante, T.; Iannitti, R.G.; Cunha, C.; De Luca, A.; Giovannini, G.; Pieraccini, G.; Zecchi, R.; D’Angelo, C.; Massi-Benedetti, C.; Fallarino, F.; et al. Tryptophan Catabolites from Microbiota Engage Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor and Balance Mucosal Reactivity via Interleukin-22. Immunity 2013, 39, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botting, N.P. Chemistry and Neurochemistry of the Kynurenine Pathway of Tryptophan Metabolism. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1995, 24, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, W.; McGuinness, A.J.; Rocks, T.; Ruusunen, A.; Cleminson, J.; Walker, A.J.; Gomes-da-Costa, S.; Lane, M.; Sanches, M.; Diaz, A.P.; et al. The Kynurenine Pathway in Major Depressive Disorder, Bipolar Disorder, and Schizophrenia: A Meta-Analysis of 101 Studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 4158–4178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawe, G.M.; Hoffman, J.M. Serotonin Signalling in the Gut—Functions, Dysfunctions and Therapeutic Targets. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 10, 473–486, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 10, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, J.M.; Yu, K.; Donaldson, G.P.; Shastri, G.G.; Ann, P.; Ma, L.; Nagler, C.R.; Ismagilov, R.F.; Mazmanian, S.K.; Hsiao, E.Y. Indigenous Bacteria from the Gut Microbiota Regulate Host Serotonin Biosynthesis. Cell 2015, 161, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, G.; Grenham, S.; Scully, P.; Fitzgerald, P.; Moloney, R.D.; Shanahan, F.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. The Microbiome-Gut-Brain Axis during Early Life Regulates the Hippocampal Serotonergic System in a Sex-Dependent Manner. Mol. Psychiatry 2013, 18, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexeev, E.E.; Lanis, J.M.; Kao, D.J.; Campbell, E.L.; Kelly, C.J.; Battista, K.D.; Gerich, M.E.; Jenkins, B.R.; Walk, S.T.; Kominsky, D.J.; et al. Microbiota-Derived Indole Metabolites Promote Human and Murine Intestinal Homeostasis through Regulation of Interleukin-10 Receptor. Am. J. Pathol. 2018, 188, 1183–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gevi, F.; Zolla, L.; Gabriele, S.; Persico, A.M. Urinary Metabolomics of Young Italian Autistic Children Supports Abnormal Tryptophan and Purine Metabolism. Mol. Autism 2016, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagan, C.; Delorme, R.; Callebert, J.; Goubran-Botros, H.; Amsellem, F.; Drouot, X.; Boudebesse, C.; Le Dudal, K.; Ngo-Nguyen, N.; Laouamri, H.; et al. The Serotonin-N-Acetylserotonin–Melatonin Pathway as a Biomarker for Autism Spectrum Disorders. Transl. Psychiatry 2014, 4, e479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launay, J.M.; Delorme, R.; Pagan, C.; Callebert, J.; Leboyer, M.; Vodovar, N. Impact of IDO Activation and Alterations in the Kynurenine Pathway on Hyperserotonemia, NAD+ Production, and AhR Activation in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandana, S.R.; Behen, M.E.; Juhász, C.; Muzik, O.; Rothermel, R.D.; Mangner, T.J.; Chakraborty, P.K.; Chugani, H.T.; Chugani, D.C. Significance of Abnormalities in Developmental Trajectory and Asymmetry of Cortical Serotonin Synthesis in Autism. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2005, 23, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenstra-VanderWeele, J.; Muller, C.L.; Iwamoto, H.; Sauer, J.E.; Owens, W.A.; Shah, C.R.; Cohen, J.; Mannangatti, P.; Jessen, T.; Thompson, B.J.; et al. Autism Gene Variant Causes Hyperserotonemia, Serotonin Receptor Hypersensitivity, Social Impairment and Repetitive Behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 5469–5474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, J.L.; Forssen, U.; Hultman, C.M.; Cnattingius, S.; Savitz, D.A.; Feychting, M.; Sparen, P. Parental Psychiatric Disorders Associated with Autism Spectrum Disorders in the Offspring. Pediatrics 2008, 121, e1357–e1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croen, L.A.; Grether, J.K.; Yoshida, C.K.; Odouli, R.; Hendrick, V. Antidepressant Use during Pregnancy and Childhood Autism Spectrum Disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2011, 68, 1104–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maes, M.; Rief, W. Diagnostic Classifications in Depression and Somatization Should Include Biomarkers, Such as Disorders in the Tryptophan Catabolite (TRYCAT) Pathway. Psychiatry Res. 2012, 196, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryn, V.; Verkerk, R.; Skjeldal, O.H.; Saugstad, O.D.; Ormstad, H. Kynurenine Pathway in Autism Spectrum Disorders in Children. Neuropsychobiology 2017, 76, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, P.J.; Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G.; Clarke, G. Kynurenine Pathway Metabolism and the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Neuropharmacology 2017, 112, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goda, K.; Kishimoto, R.; Shimizu, S.; Hamane, Y.; Ueda, M. Quinolinic Acid and Active Oxygens. Possible Contribution of Active Oxygens during Cell Death in the Brain. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1996, 398, 247–254. [Google Scholar]

- Uehara, J.M.; Gomez Acosta, M.; Bello, E.P.; Belforte, J.E. Early Postnatal NMDA Receptor Ablation in Cortical Interneurons Impairs Affective State Discrimination and Social Functioning. Neuropsychopharmacology 2025, 50, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Fan, Y.; Xu, L.; Yu, Z.; Wang, S.; Xu, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, W.; Wu, L.; et al. Microbiome and Tryptophan Metabolomics Analysis in Adolescent Depression: Roles of the Gut Microbiota in the Regulation of Tryptophan-Derived Neurotransmitters and Behaviors in Human and Mice. Microbiome 2023, 11, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Mu, C.L.; Farzi, A.; Zhu, W.Y. Tryptophan Metabolism: A Link between the Gut Microbiota and Brain. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummelte, S.; Mc Glanaghy, E.; Bonnin, A.; Oberlander, T.F. Developmental Changes in Serotonin Signaling: Implications for Early Brain Function, Behavior and Adaptation. Neuroscience 2017, 342, 212–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.; Tangen, Ä.; Farde, L.; Bölte, S.; Halldin, C.; Borg, J.; Lundberg, J. Serotonin Transporter Availability in Adults with Autism-a Positron Emission Tomography Study. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 1647–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugani, D.C.; Muzik, O.; Behen, M.; Rothermel, R.; Janisse, J.J.; Lee, J.; Chugani, H.T. Developmental Changes in Brain Serotonin Synthesis Capacity in Autistic and Nonautistic Children. Ann. Neurol. 1999, 45, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefevre, A.; Richard, N.; Mottolese, R.; Leboyer, M.; Sirigu, A. An Association Between Serotonin 1A Receptor, Gray Matter Volume, and Sociability in Healthy Subjects and in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Autism Res. 2020, 13, 1843–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, L.Y.; Alves, N.D.; Del Colle, A.; Talati, A.; Najjar, S.A.; Bouchard, V.; Gillet, V.; Tong, Y.; Huang, Z.; Browning, K.N.; et al. Intestinal Epithelial Serotonin as a Novel Target for Treating Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction and Mood. Gastroenterology 2025, 168, 754–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillsley, K.; Kirkup, A.J.; Grundy, D. Direct and Indirect Actions of 5-Hydroxytryptamine on the Discharge of Mesenteric Afferent Fibres Innervating the Rat Jejunum. J. Physiol. 1998, 506, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeroff, C.B.; Mayberg, H.S.; Krahl, S.E.; McNamara, J.; Frazer, A.; Henry, T.R.; George, M.S.; Charney, D.S.; Brannan, S.K. VNS Therapy in Treatment-Resistant Depression: Clinical Evidence and Putative Neurobiological Mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006, 31, 1345–1355, Erratum in Neuropsychopharmacology 2006, 31, 2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamoorthy, R.; Radhakrishnan, M.; Borah, M. Antidepressant-like Effects of Serotonin Type-3 Antagonist, Ondansetron: An Investigation in Behaviour-Based Rodent Models. Behav. Pharmacol. 2008, 19, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghia, J.E.; Li, N.; Wang, H.; Collins, M.; Deng, Y.; El-Sharkawy, R.T.; Côté, F.; Mallet, J.; Khan, W.I. Serotonin Has a Key Role in Pathogenesis of Experimental Colitis. Gastroenterology 2009, 137, 1649–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulceri, F.; Morelli, M.; Santocchi, E.; Cena, H.; Del Bianco, T.; Narzisi, A.; Calderoni, S.; Muratori, F. Gastrointestinal Symptoms and Behavioral Problems in Preschoolers with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Dig. Liver Dis. 2016, 48, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reigstad, C.S.; Salmonson, C.E.; Rainey, J.F.; Szurszewski, J.H.; Linden, D.R.; Sonnenburg, J.L.; Farrugia, G.; Kashyap, P.C. Gut Microbes Promote Colonic Serotonin Production through an Effect of Short-Chain Fatty Acids on Enterochromaffin Cells. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 1395–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Qian, C.; Huo, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Ying, Y.; Wang, B.; Yang, H.; Yeerken, A.; Wang, T.; et al. Gut-Derived Lactic Acid Enhances Tryptophan to 5-Hydroxytryptamine in Regulation of Anxiety via Akkermansia Muciniphila. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2447834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needham, B.D.; Adame, M.D.; Serena, G.; Rose, D.R.; Preston, G.M.; Conrad, M.C.; Campbell, A.S.; Donabedian, D.H.; Fasano, A.; Ashwood, P.; et al. Plasma and Fecal Metabolite Profiles in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 89, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pernomian, L.; Duarte-Silva, M.; de Barros Cardoso, C.R. The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AHR) as a Potential Target for the Control of Intestinal Inflammation: Insights from an Immune and Bacteria Sensor Receptor. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 59, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothhammer, V.; Mascanfroni, I.D.; Bunse, L.; Takenaka, M.C.; Kenison, J.E.; Mayo, L.; Chao, C.C.; Patel, B.; Yan, R.; Blain, M.; et al. Type I Interferons and Microbial Metabolites of Tryptophan Modulate Astrocyte Activity and Central Nervous System Inflammation via the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suez, J.; Zmora, N.; Segal, E.; Elinav, E. The Pros, Cons, and Many Unknowns of Probiotics. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 716–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, M.I.; Reid, G.; ter Haar, J.A. Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GR-1, a.k.a. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1: Past and Future Perspectives. Trends Microbiol. 2021, 29, 747–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathayat, D.; Closs, G.; Helmy, Y.A.; Deblais, L.; Srivastava, V.; Rajashekara, G. In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation of Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG and Bifidobacterium lactis Bb12 Against Avian Pathogenic Escherichia coli and Identification of Novel Probiotic-Derived Bioactive Peptides. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2022, 14, 1012–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikindas, M.L.; Weeks, R.; Drider, D.; Chistyakov, V.A.; Dicks, L.M. Functions and Emerging Applications of Bacteriocins. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018, 49, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilbronner, S.; Krismer, B.; Brötz-Oesterhelt, H.; Peschel, A. The Microbiome-Shaping Roles of Bacteriocins. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 726–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drider, D.; Bendali, F.; Naghmouchi, K.; Chikindas, M.L. Bacteriocins: Not Only Antibacterial Agents. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2016, 8, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouriani, F.H.; Torkamaneh, M.; Torfeh, M.; Ashrafian, F.; Aghamohammad, S.; Rohani, M. Native Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium Probiotics Modulate Autophagy Genes and Exert Anti-Inflammatory Effect. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isolauri, E.; Kirjavainen, P.V.; Salminen, S. Probiotics: A Role in the Treatment of Intestinal Infection and Inflammation? Gut 2002, 50, iii54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, Q.; Chen, Q.; Mao, X.; Wang, G.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W. Bifidobacterium longum CCFM1077 Ameliorated Neurotransmitter Disorder and Neuroinflammation Closely Linked to Regulation in the Kynurenine Pathway of Autistic-like Rats. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, B.M.; Charych, E.; Lee, A.W.; Möller, T. Kynurenines in CNS Disease: Regulation by Inflammatory Cytokines. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.; Guan, C.; Wang, T.; Mu, G.; Tuo, Y. Indole-3-Lactic Acid, a Tryptophan Metabolite of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum DPUL-S164, Improved Intestinal Barrier Damage by Activating AhR and Nrf2 Signaling Pathways. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 18792–18801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; Lin, T.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Sun, Y.; Wang, D.; Ye, J.; Zhang, Y.; Kou, R.; Zhao, B.; et al. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Regulates Intestinal Physiology and Enteric Neurons in IBS through Microbial Tryptophan Metabolites. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 17989–18002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Xiao, L.; Fu, Y.; Shao, Z.; Jing, Z.; Yuan, J.; Xie, Y.; Guo, J.; Wang, Y.; Geng, W. Neuroprotective Effects of Probiotics on Anxiety- and Depression-like Disorders in Stressed Mice by Modulating Tryptophan Metabolism and the Gut Microbiota. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 2895–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, R.S.; Sanacora, G.; Krystal, J.H. Altered Connectivity in Depression: GABA and Glutamate Neurotransmitter Deficits and Reversal by Novel Treatments. Neuron 2019, 102, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, J.A.; Forsythe, P.; Chew, M.V.; Escaravage, E.; Savignac, H.M.; Dinan, T.G.; Bienenstock, J.; Cryan, J.F. Ingestion of Lactobacillus Strain Regulates Emotional Behavior and Central GABA Receptor Expression in a Mouse via the Vagus Nerve. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 16050–16055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Jia, X.; Lin, J.; Xiao, L.; Liu, D.; Liang, M. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum DMDL 9010 Alleviates Dextran Sodium Sulfate (DSS)-Induced Colitis and Behavioral Disorders by Facilitating Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis Balance. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, P.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, E. A Review of Probiotics in the Treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorders: Perspectives from the Gut–Brain Axis. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1123462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.F.; Zhuang, Y.; Jin, S.B.; Zhang, S.L.; Yang, W.W. Probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) Restores Intestinal Dysbacteriosis to Alleviate Upregulated Inflammatory Cytokines Triggered by Femoral Diaphyseal Fracture in Adolescent Rodent Model. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 25, 376–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Microbes, Immunity, and Behavior: Psychoneuroimmunology Meets the Microbiome. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robb, A.S. Managing Irritability and Aggression in Autism Spectrum Disorders in Children and Adolescents. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2010, 16, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bearss, K.; Johnson, C.; Smith, T.; Lecavalier, L.; Swiezy, N.; Aman, M.; McAdam, D.B.; Butter, E.; Stillitano, C.; Minshawi, N.; et al. Effect of Parent Training vs Parent Education on Behavioral Problems in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. JAMA 2015, 313, 1524, Erratum in JAMA 2016, 316, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatham, C.H.; Taylor, K.I.; Charman, T.; Liogier D’ardhuy, X.; Eule, E.; Fedele, A.; Hardan, A.Y.; Loth, E.; Murtagh, L.; del Valle Rubido, M.; et al. Adaptive Behavior in Autism: Minimal Clinically Important Differences on the Vineland-II. Autism Res. 2018, 11, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, S.Y.; El Gendy, Y.G.; Mehanna, N.S.; El-Senousy, W.M.; El-Feki, H.S.A.; Saad, K.; El-Asheer, O.M. The Role of Probiotics in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Prospective, Open-Label Study. Nutr. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidetti, C.; Salvini, E.; Viri, M.; Deidda, F.; Amoruso, A.; Visciglia, A.; Drago, L.; Calgaro, M.; Vitulo, N.; Pane, M.; et al. Randomized Double-Blind Crossover Study for Evaluating a Probiotic Mixture on Gastrointestinal and Behavioral Symptoms of Autistic Children. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; Zeng, T.; Lu, C.W.; Li, D.Y.; Liu, Y.Y.; Li, B.M.; Chen, S.Q.; Deng, Y.H. Efficacy and Safety of Bacteroides fragilis BF839 for Pediatric Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1447059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narula Khanna, H.; Roy, S.; Shaikh, A.; Chhabra, R.; Uddin, A. Impact of Probiotic Supplements on Behavioural and Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Randomised Controlled Trial. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2025, 9, e003045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, W.; Lin, B.; Ma, T.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, W.; Zhou, R.; Kwok, L.Y.; Sun, Z.; Zhu, C.; et al. Omic Characterizing and Targeting Gut Dysbiosis in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Symptom Alleviation through Combined Probiotic and Medium-Carbohydrate Diet Intervention—A Pilot Study. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2434675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, N.; Yang, J.J.; Zhao, D.M.; Chen, B.; Zhang, G.Q.; Chen, S.; Cao, R.F.; Yu, H.; Zhao, C.Y.; et al. Probiotics and Fructo-Oligosaccharide Intervention Modulate the Microbiota-Gut Brain Axis to Improve Autism Spectrum Reducing Also the Hyper-Serotonergic State and the Dopamine Metabolism Disorder. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 157, 104784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.W.; Wang, J.E.; Sun, F.J.; Huang, Y.H.; Chen, H.J. Probiotic Intervention in Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Taiwan: A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2023, 109, 102256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.-J.; Liu, J.; Liu, K.; Koh, M.; Sherman, H.; Liu, S.; Tian, R.; Sukijthamapan, P.; Wang, J.; Fong, M.; et al. Probiotic and Oxytocin Combination Therapy in Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Pilot Trial. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eugene Arnold, L.; Luna, R.A.; Williams, K.; Chan, J.; Parker, R.A.; Wu, Q.; Hollway, J.A.; Jeffs, A.; Lu, F.; Coury, D.L.; et al. Probiotics for Gastrointestinal Symptoms and Quality of Life in Autism: A Placebo-Controlled Pilot Trial. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2019, 29, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santocchi, E.; Guiducci, L.; Prosperi, M.; Calderoni, S.; Gaggini, M.; Apicella, F.; Tancredi, R.; Billeci, L.; Mastromarino, P.; Grossi, E.; et al. Effects of Probiotic Supplementation on Gastrointestinal, Sensory and Core Symptoms in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 550593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billeci, L.; Callara, A.L.; Guiducci, L.; Prosperi, M.; Morales, M.A.; Calderoni, S.; Muratori, F.; Santocchi, E. A Randomized Controlled Trial into the Effects of Probiotics on Electroencephalography in Preschoolers with Autism. Autism 2023, 27, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novau-Ferré, N.; Papandreou, C.; Rojo-Marticella, M.; Canals-Sans, J.; Bulló, M. Gut Microbiome Differences in Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder and Effects of Probiotic Supplementation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2025, 161, 105003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmora, N.; Zilberman-Schapira, G.; Suez, J.; Mor, U.; Dori-Bachash, M.; Bashiardes, S.; Kotler, E.; Zur, M.; Regev-Lehavi, D.; Brik, R.B.-Z.; et al. Personalized Gut Mucosal Colonization Resistance to Empiric Probiotics Is Associated with Unique Host and Microbiome Features. Cell 2018, 174, 1388–1405.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, C.X.; Henders, A.K.; Alvares, G.A.; Wood, D.L.A.; Krause, L.; Tyson, G.W.; Restuadi, R.; Wallace, L.; McLaren, T.; Hansell, N.K.; et al. Autism-Related Dietary Preferences Mediate Autism-Gut Microbiome Associations. Cell 2021, 184, 5916–5931.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wong, O.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Lu, W.; Cheung, C.P.; Ching, J.Y.L.; Cheong, P.K.; Chan, S.; Leung, P.; et al. Distinct Diet-Microbiome Associations in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Nat. Commun. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.A.; Rinaman, L.; Cryan, J.F. Stress & the Gut-Brain Axis: Regulation by the Microbiome. Neurobiol. Stress 2017, 7, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, C.N.; Nielsen, S.; Kæstel, P.; Brockmann, E.; Bennedsen, M.; Christensen, H.R.; Eskesen, D.C.; Jacobsen, B.L.; Michaelsen, K.F. Dose–Response Study of Probiotic Bacteria Bifidobacterium animalis subsp lactis BB-12 and Lactobacillus paracasei subsp paracasei CRL-341 in Healthy Young Adults. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 60, 1284–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, L.V.; Hecht, G.; Sanders, M.E.; Goff, D.A.; Goldstein, E.J.C.; Hill, C.; Johnson, S.; Kashi, M.R.; Kullar, R.; Marco, M.L.; et al. Recommendations to Improve Quality of Probiotic Systematic Reviews with Meta-Analyses. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2346872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFarland, L.V. Efficacy of Single-Strain Probiotics Versus Multi-Strain Mixtures: Systematic Review of Strain and Disease Specificity. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2021, 66, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, C.M.C.; Gibson, G.R.; Rowland, I. In Vitro Evaluation of Single- and Multi-Strain Probiotics: Inter-Species Inhibition between Probiotic Strains, and Inhibition of Pathogens. Anaerobe 2012, 18, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allan, N.P.; Yamamoto, B.Y.; Kunihiro, B.P.; Nunokawa, C.K.L.; Rubas, N.C.; Wells, R.K.; Umeda, L.; Phankitnirundorn, K.; Torres, A.; Peres, R.; et al. Ketogenic Diet Induced Shifts in the Gut Microbiome Associate with Changes to Inflammatory Cytokines and Brain-Related MiRNAs in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo-Galvis, C.A.; Trejos-Gallego, D.M.; Correa-Salazar, C.; Triviño-Valencia, J.; Valencia-Buitrago, M.; Ruiz-Pulecio, A.F.; Méndez-Ramírez, L.F.; Zabaleta, J.; Meñaca-Puentes, M.A.; Ruiz-Villa, C.A.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory Diet and Probiotic Supplementation as Strategies to Modulate Immune Dysregulation in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, J.; Calvo, D.C.; Nair, D.; Jain, S.; Montagne, T.; Dietsche, S.; Blanchard, K.; Treadwell, S.; Adams, J.; Krajmalnik-Brown, R. Precision Synbiotics Increase Gut Microbiome Diversity and Improve Gastrointestinal Symptoms in a Pilot Open-Label Study for Autism Spectrum Disorder. mSystems 2024, 9, e00503-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davico, C.; Secci, I.; Vendrametto, V.; Vitiello, B. Pharmacological Treatments in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Narrative Review. J. Psychopathol. 2023, 29, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotowska, M.; Kołodziej, M.; Szajewska, H.; Łukasik, J. The Impact of Probiotics on Core Autism Symptoms—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2024, 63, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, M.L.; Tachon, S. Environmental Factors Influencing the Efficacy of Probiotic Bacteria. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2013, 24, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kort, R. Personalized Therapy with Probiotics from the Host by TripleA. Trends Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 291–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, B.M.; Gutiérrez-Vázquez, C.; Sanmarco, L.M.; da Silva Pereira, J.A.; Li, Z.; Plasencia, A.; Hewson, P.; Cox, L.M.; O’Brien, M.; Chen, S.K.; et al. Self-Tunable Engineered Yeast Probiotics for the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1212–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metabolic Pathway | Primary Sites | Key Enzymes | Major Metabolites | Main Functions/Effects | Related Diseases or Physiological Processes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kynurenine pathway (KP) | Liver, immune cells, epithelial cells | TDO, IDO1, IDO2 | Kynurenine (Kyn), kynurenic acid (KYNA), quinolinic acid (QA), NAD+ | Immune regulation, energy metabolism, neuroregulation | Alzheimer’s disease, depression, schizophrenia, etc. |

| Serotonin pathway (5-HT) | Intestinal enterochromaffin cells, raphe nuclei neurons | TPH1, TPH2 | Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) | Regulates gut motility and secretion, vasodilation, neurotransmission, mood and cognition | Mood disorders, irritable bowel syndrome, etc. |

| Indole pathway | Gut microbiota | Bacterial tryptophanase and related enzymes | Indole, indole acrylic acid, indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), indole-3-propionic acid (IPA), etc. | Activates AhR, promotes IL-6/IL-17/IL-22, maintains intestinal barrier and homeostasis | Inflammatory bowel disease, metabolic syndrome, etc. |

| Sample Size | Intervention/Strain (s) | CFU | Duration | Outcome Measures | Main Findings (Behavior/Symptom Improvement) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASD children (n = 30); healthy controls (n = 30) | Multi-strain probiotics: Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium longum | 1 × 108 | 3 months | Behavioral scales (ATEC, etc.), GI six indices | Significant improvement in disruptive behavior, antisocial behavior, anxiety, and communication deficits | Shaaban et al., 2018 [87] |

| ASD children (n = 61) | Multi-strain probiotics: L. fermentum LF10, L. salivarius LS03, L. plantarum LP01, B. longum DLBL07–11 | 1 × 1010 | 8 months total (each intervention period 3 months + washout) | GI Severity Index, PSI, VABS, ASRS | In a subset of ASD participants, behavioral severity decreased; communication/adaptive behavior and parent stress improved; GI symptoms generally improved | Guidetti et al., 2022 [88] |

| ASD children (n = 60, 2–10 years) | Bacteroides fragilis BF839 | 1 × 106 | 16 weeks | Behavioral scales and GI symptom assessments, ABC, CARS, SRS, GSRS, etc. | Improved behavior and GI symptoms in ASD children (overall and in some subgroups significant) | Lin et al., 2024 [89] |

| ASD children (n = 180) | Powder formulation containing 12 probiotic strains | 9 × 109 | 3 months | SRS-2, ABC-2, GSI | Probiotic treatment significantly improved ASD-related behaviors and gastrointestinal symptoms, with behavioral gains paralleling GSI improvement. | Khanna et al., 2025 [90] |

| ASD children (n = 53, 3–12 years) | Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis Probio-M8 + moderate-carbohydrate diet | 1 × 1011 | 12 weeks | CARS, GSRS | Significant improvements in ASD and GI symptoms; modulation of glutamate/GABA/5-HT-related metabolism | Li et al., 2024 [91] |

| ASD children (n = 26) | Multi-strain probiotics + FOS: B. infantis Bi-26, L. rhamnosus HN001, B. lactis BL-04, L. paracasei LPC-37 | 1 × 1010 | Up to 108 days (assessed at days 0/30/60/108) | ATEC, GI indices; SCFAs; neurotransmitters/metabolites incl. 5-HT/HVA | Reduced ASD and GI symptoms; SCFAs increased; hyper-serotonergic state alleviated; some putative pathobionts decreased | Wang et al., 2020 [92] |

| ASD children (82 randomized; 86 assessed; 2.5–7 years) | Lactobacillus plantarum PS128 | 3 × 1010 | 4 months | Attention, hyperactivity, impulsivity, oppositional defiant behaviors | Secondary outcomes improved; no significant improvement in core symptoms | Liu et al., 2023 [93] |

| 35 participants | Single-strain Lactobacillus plantarum PS128; from week 16 onward, both groups additionally received intranasal OXT | 6 × 1010 | 28 weeks | SRS, ABC, CGI-I, GI (GSI), inflammatory markers, fecal microbiota | PS128 combined with oxytocin produced greater social and behavioral improvements than oxytocin alone, suggesting a synergistic effect. | Kong et al., 2021 [94] |

| ASD children (n = 13, 3–12 years) | Multi-strain probiotics (VSL# 3/Visbiome) | 9 × 1011 | 8 weeks | Behavioral and GI-related scales | Improvements vs. baseline but not statistically significant vs. placebo (small sample size) | Arnold et al., 2019 [95] |

| ASD children (n = 85) | Multi-strain probiotic DSF (De Simone Formulation) | 4.5 × 1011 | 6 months | ADOS-2, etc. | Overall no significant improvement in core symptoms | Santocchi et al., 2020 [96] |

| ASD children (n = 46, EEG subset) | Multistrain Vivomixx® (S. thermophilus, B. breve, B. longum, B. infantis, L. acidophilus, L. plantarum, L. paracasei, L. delbrueckii) | No specific explanation | 6 months | ADOS-2, CARS, SCQ, RBS-R, CBCL, VABS-II, GSI, and resting-state EEG (power, coherence, asymmetry) | Resting-state EEG shifted toward a more typical activity pattern, while behavioral changes were only modest. | Billeci et al., 2023 [97] |

| ADHD children (n =39) ASD children (n = 41) | Multistrain probiotic preparation | 1 × 109 | 12 weeks | SRS-2, CBCL, BRIEF-2, SDSC, CPT/K-CPT2, fecal 16S rRNA microbiome | Probiotic intervention markedly altered gut microbiota, including increased alpha diversity in ASD, but yielded no consistent robust behavioral benefit. | Novau-Ferré et al., 2025 [98] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cheng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Zheng, C.; Ma, T.; Sun, Z. The Gut Microbiota–Tryptophan–Brain Axis in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A New Frontier for Probiotic Intervention. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020312

Cheng Y, Zhang L, Li Y, Zheng C, Ma T, Sun Z. The Gut Microbiota–Tryptophan–Brain Axis in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A New Frontier for Probiotic Intervention. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(2):312. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020312

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Yi, Liangyu Zhang, Yalin Li, Chunru Zheng, Teng Ma, and Zhihong Sun. 2026. "The Gut Microbiota–Tryptophan–Brain Axis in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A New Frontier for Probiotic Intervention" Microorganisms 14, no. 2: 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020312

APA StyleCheng, Y., Zhang, L., Li, Y., Zheng, C., Ma, T., & Sun, Z. (2026). The Gut Microbiota–Tryptophan–Brain Axis in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A New Frontier for Probiotic Intervention. Microorganisms, 14(2), 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020312