Initial Analysis of Plant Soil for Evidence of Pathogens Associated with a Disease of Seedling Ocotea monteverdensis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Site and Collections

2.2. Soil Environmental Metrics

2.3. DNA Extraction, Sequencing, and Bioinformatics

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Differences in Soil Carbon and Nitrogen Metrics

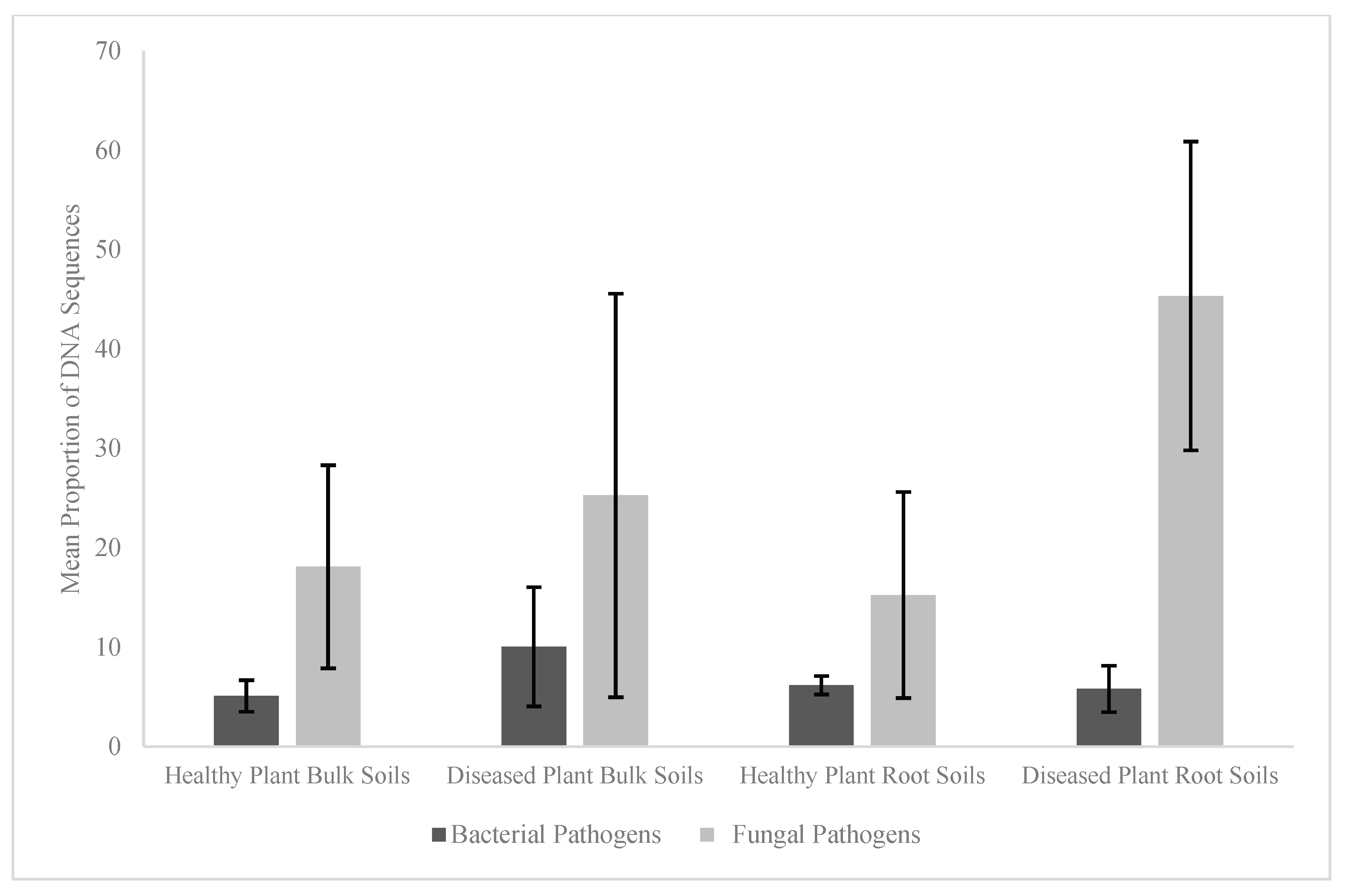

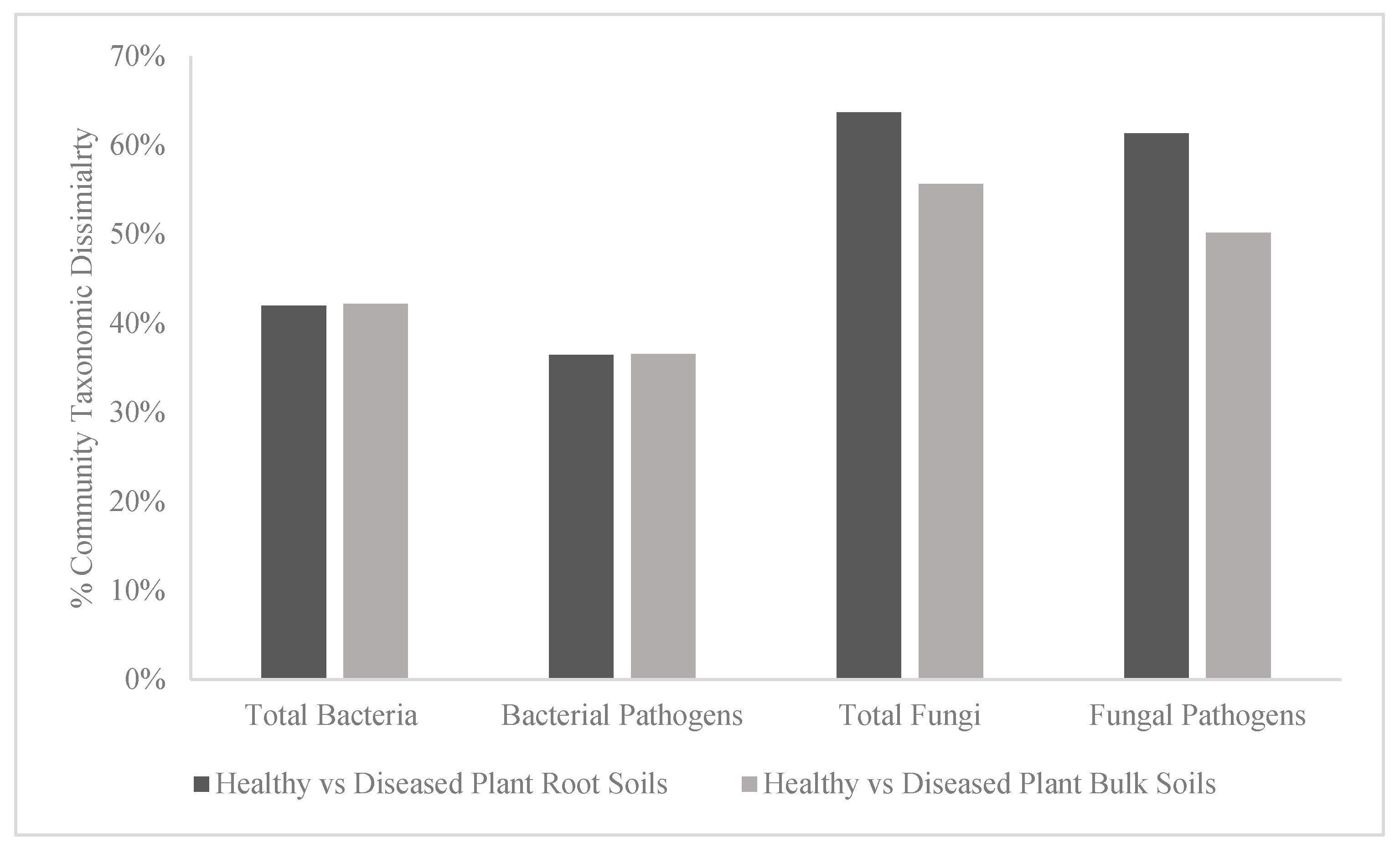

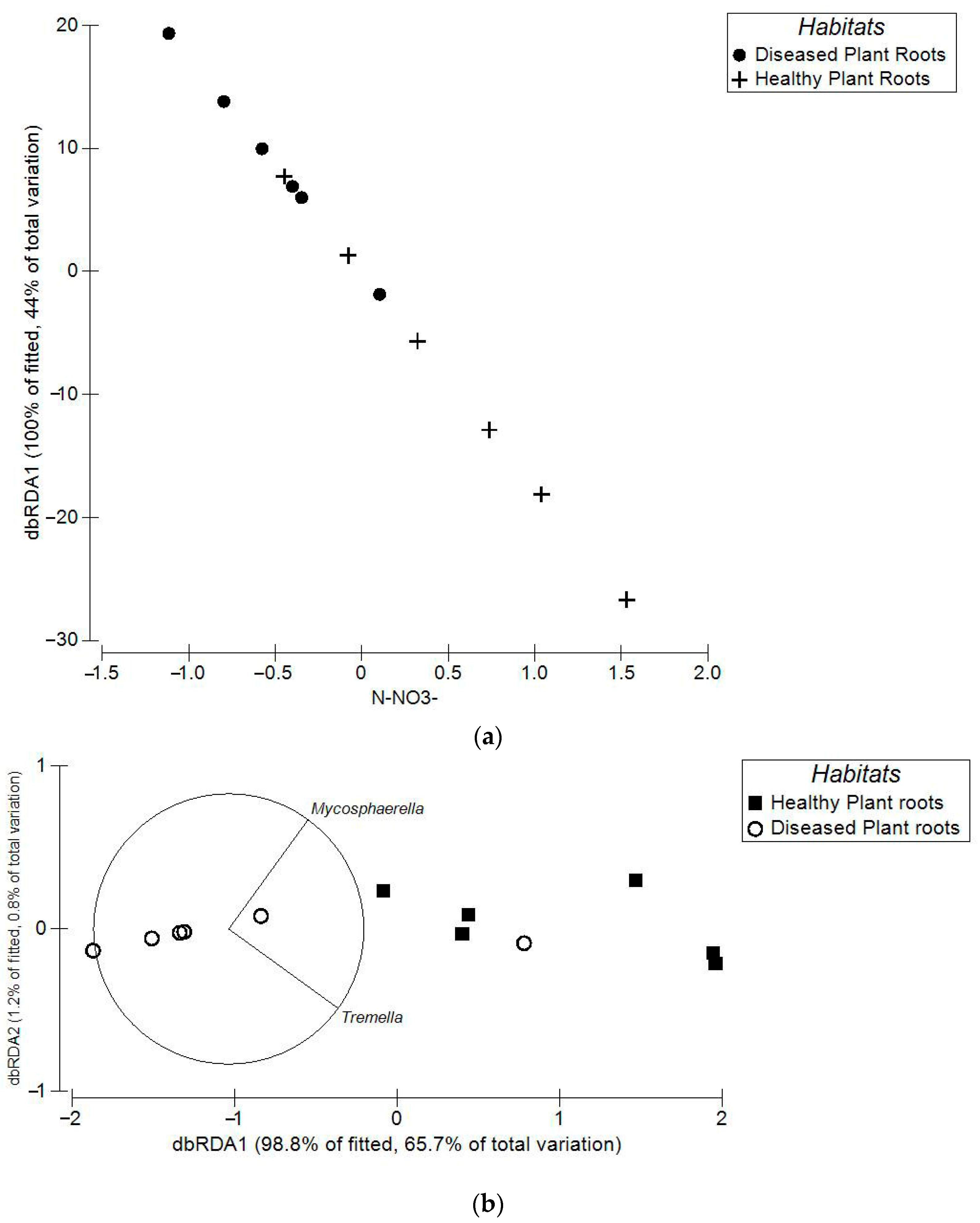

3.2. Differences in Community Compositions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hazelwood, K.; Beck, H.; Paine, C.T. Negative density dependence in the mortality and growth of tropical tree seedlings is strong and primarily caused by fungal pathogens. J. Ecol. 2021, 109, 1909–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.L.; Toda, M.; Chiller, T.; Brunkard, J.M.; Litvintseva, A.P. Effects of climate change on fungal infections. PLoS Pathog. 2024, 20, e1012219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdon, J.J.; Zhan, J. Climate change and disease in plant communities. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.N.; Ren, M.; Zhan, J. Modeling plant diseases under climate change: Evolutionary perspectives. Trends Plant Sci. 2023, 28, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/ (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Joslin, J.D.; Haber, W.A.; Hamilton, D. Ocotea monteverdensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, e.T48724260A117762662. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/48724260/117762662 (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Powell, G.V.; Bjork, R.D. Habitat linkages and the conservation of tropical diversity as indicated by seasonal migrations of the three-wattled bellbird. Conserv. Biol. 2004, 18, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, D.; Singleton, R.; Joslin, J.D. Resource tracking and its conservation implications for an obligate frugivore (Procnias tricarunculatus, the three-wattled bellbird). Biotropica 2018, 50, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, W.; Zuchowski, W.; Bello, E. An Introduction to Cloud Forest Trees: Monteverde, Costa Rica, 2nd ed.; Mountain Gem Publications: Monteverde, Costa Rica, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wheelwright, N.; Nadkarni, N. (Eds.) Monteverde: Ecology and Conservation of a Tropical Cloud Forest; Bowdoin’s Scholars’ Bookshelf: Brunswick, ME, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Guindon, C. The Importance of Forest Fragments to the Maintenance of Regional Biodiversity Surrounding a Tropical Montane Reserve, Costa Rica. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of the School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, C.A.; Guindon, C.; Haber, W.; Hamilton, D.; Murray, K.G. Importancia de Los Fragmentos de Bosque, Los Arboles Dispersos and Las Cortinas Rompevientos Para la Biodiversidad Local y Regional in Evaluación y Conservación de Biodiversidad en Paisajes Fragmentados de Mesoamérica; Editorial INBio: Santo Domingo de Heredia, Costa Rica, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sciara, J.; Fite, C. Environmental Factors That Contribute to the Reproductive Ecology of Ocotea monteverdensis; Report to the CIEE Sustainability Program: Monteverde, Costa Rica, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, D.; Parshall, T.; Vargas Berocal, L.; Alvarado Mendez, R.; Goldsmith, G.; Donovan, T. Optimizing the restoration practitioner’s role: Evaluating seedling characteristics, maintenance, and cost-effective strategies for tropical forest restoration. Ecol. Rest. 2025. submit. [Google Scholar]

- Milici, V.R.; Comita, L.S.; Bagchi, R. Foliar disease incidence in a tropical seedling community is density dependent and varies along a regional precipitation gradient. J. Ecol. 2024, 112, 642–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, J.; Poveda, L. Lauraceae. In Manual de plantas de Costa Rica, Vol. VI: Dicotiledoneas (Haloragaceae-hytolaccaceae); Hammel, B.E., Grayum, M.H., Herrera, C., Zamora, N., Eds.; Missouri Botanical Garden Press: Louis, MO, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tropicos.org. Tropicos v3.4.2 Missouri Botanical Garden, 4344 Shaw Boulevard—Saint Louis, Missouri 63110. 2017. Available online: https://www.tropicos.org/name/17804917 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- LaVal, R. Datos Casa LaVal. Available online: https://monteverde-institute.org/research-and-innovation-2/#DC1 (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Anderson, J.M.; Ingram, J.S.I. Tropical Soil Biology and Fertility: A Handbook of Methods, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Alef, K.; Nannipieri, P. Methods in Applied Soil Microbiology and Biochemistry; Elsevier, Academic Press: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gardes, M.; Bruns, T.D. ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes—Application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Mol. Ecol. 1993, 2, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Lauber, C.L.; Walters, W.A.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Lozupone, C.A.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Fierer, N.; Knight, R. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 4, 516–4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGee, K.M.; Eaton, W.D.; Shokralla, S.; Hajibabaei, M. Determinants of soil bacterial and fungal community composition toward carbon-use efficiency across primary and secondary forests in a Costa Rican conservation area. Microb. Ecol. 2018, 10, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundquist, A.; Bigdeli, S.; Jalili, R.; Druzin, M.L.; Waller, S.; Pullen, K.M.; El-Sayed, Y.Y.; Taslimi, M.M.; Batzoglou, S.; Ronaghi, M. Bacterial flora-typing with targeted, chip-based pyrosequencing. BMC Microbiol. 2007, 7, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, T.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR: Protocols and Applications—A Laboratory Manual; Innis, N., Gelfand, D., Sninsky, J., White, T., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.-L.; Porras-Alfaro, A.; Kuske, C.R.; Eichorst, S.A.; Xie, G. Accurate, rapid taxonomic classification of fungal large-subunit rRNA genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 1523–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, S.; Xu, Z.Z.; Peddada, S.; Amir, A.; Bittinger, K.; Gonzalez, A.; Lozupone, C.; Zaneveld, J.R.; Vázquez-Baeza, Y.; Birmingham, A.; et al. Normalization and microbial differential abundance strategies depend upon data characteristics. Microbiome 2017, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, M.J.; Gorley, R.N.; Clarke, R.K. PERMANOVA+ for Primer: Guide to Software and Statistical Methods; PRIMER-E Ltd.: Plymouth, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.J.; Willis, T. Canonical analysis of principal coordinates: A useful method of constrained ordination for ecology. Ecology 2003, 84, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.R.; Gorley, R.N. PRIMER v6: User Manual; PRIMER-E Ltd.: Plymouth, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Spigaglia, P.; Barbanti, F.; Marocchi, F.; Mastroleo, M.; Baretta, M.; Ferrante, P.; Caboni, E.; Lucioli, S.; Scortichini, M. Clostridium bifermentans and C. subterminale are associated with kiwifruit vine decline, known as moria, in Italy. Plant Pathol. 2020, 69, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, M.; Mur, L.A.J.; Shen, Q.; Guo, S. Unravelling the roles of nitrogen nutrition in plant disease defenses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mur, L.A.J.; Simpson, C.; Kumari, A.; Gupta, A.K.; Gupta, K.J. Moving nitrogen to the centre of plant defence against pathogens. Ann. Bot. 2017, 119, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crous, P.W. Taxonomy and phylogeny of the genus Mycosphaerella and its anamorphs. Fungal Divers. 2009, 38, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Crous, P.W.; Kang, J.C.; Braun, U. A phylogenetic redefinition of anamorph genera in Mycosphaerella based on ITS rDNA sequence and morphology. Mycologia 2001, 93, 1081–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.N.; Gottwald, T.R.; Timmer, L.W. Environmental factors affecting the release and dispersal of ascospores of Mycosphaerella citri. Phytopathology 2003, 93, 1031–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roger, C.; Tivoli, B.; Huber, L. Effects of temperature and moisture on disease and fruit body development of Mycosphaerella pinodes on pea (Pisum sativum). Plant Pathol. 1999, 48, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicent, A.; Bassimba, D.D.M.; Intrigliolo, D.S. Effects of temperature, water regime and irrigation system on the release of ascospores of Mycosphaerella nawae, causal agent of circular leaf spot of persimmon. Plant Pathol. 2011, 60, 890–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakeham, A.J.; Kennedy, R. Risk assessment methods for the ringspot pathogen Mycosphaerella brassicola in vegetable Brassica crops. Plant Dis. 2010, 94, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Nelson, S. Cercospora Leaf Spot and Berry Blotch of Coffee; Plant Disease; PD-41; University of Hawaii: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2008; Available online: https://www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/oc/freepubs/pdf/PD-41.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Gaitán, A.L. Compendium of Coffee Disease and Pests; Amer. Phytopathol. Soc.: Saint Paul, MN, USA, 2015; pp. 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Rosling, A.; Cox, F.; Cruz-Martinez, K.; Ihrmark, K.; Grelet, G.-A.; Lindahl, B.D.; Menkis, A.; James, T.Y. Archaeorhizomycetes: Unearthing an ancient class of ubiquitous soil fungi. Science 2011, 333, 876–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosling, A.; Timling, I.; Taylor, D.L. Archaeorhizomycetes: Patterns of distribution and abundance in soil. In Genomics of Soil- and PlantAssociated Fungi. Soil Biology; Horwitz, B., Mukherjee, P., Mukherjee, M., Kubicek, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 333–349. [Google Scholar]

- Clemmensen, K.E.; Finlay, R.D.; Dahlberg, A.; Stenlid, J.; Wardle, D.A.; Lindahl, B.D. Carbon sequestration is related to mycorrhizal fungal community shifts during long-term succession in boreal forests. N. Phytol. 2015, 205, 1525–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrino-Kyker, S.R.; Kluber, L.A.; Petersen, S.M.; Coyle, K.P.; Hewins, C.R.; DeForest, J.L.; Smemo, K.A.; Burke, D.J.; Anderson, I. Mycorrhizal fungal communities respond to experimental elevation of soil pH and P availability in temperate hardwood forests. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2016, 92, fiw024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbina, H.; Breed, M.F.; Zhao, W.; Gurrala, K.L.; Andersson, S.G.E.; Ågren, J.; Baldauf, S.; Rosling, A. Specificity in Arabidopsis thaliana recruitment of root fungal communities from soil and rhizosphere. Fungal Biol. 2018, 122, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto-Figueroa, E.A.; Seddon, E.; Yashiro, E.; Buri, A.; Niculita-Hirzel, H.; van der Meer, J.R.; Guisan, A. Archaeorhizomycetes spatial distribution in soils along wide elevational and environmental gradients reveal co-abundance patterns with other fungal saprobes and potential weathering capacities. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, H.F.; Classen, A.T.; Austin, E.E.; Norby, R.J.; Schadt, C.W. Soil microbial community responses to multiple experimental climate change drivers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindahl, B.D.; de Boer, W.; Finlay, R.D. Disruption of root carbon transport into forest humus stimulates fungal opportunists at the expense of mycorrhizal fungi. ISME J. 2010, 4, 872–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letcher, P.M.; Powell, M.J. A taxonomic summary and revision of Rozella (Cryptomycota). IMA Fungus 2018, 9, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gleason, F.; Carney, L.; Lilje, O.; Glockling, S. Ecological potentials of species of Rozella (Cryptomycota). Fungal Ecol. 2012, 5, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, A.V.; Pires-Zottarelli, C.L.A.; Barrera, M.D.; Gleason, F.H. Diversity, role in decomposition and succession of zoosporic fungi and straminipiles on submerged decaying leaves in a woodland stream. Hydrobiologia 2011, 659, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Diseased Plant | Healthy Plant | Mann–Whitney | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metric | Root Soil | Root Soil | p Value |

| TN | 58.13 ± 11.27 | 44.03 ± 11.18 | 0.052 |

| TOC | 763.5 ± 184.78 | 665 ± 98.56 | 0.093 |

| NH4+ | 6.12 ± 3.01 | 2.91 ± 2.04 | 0.055 |

| NO3− | 60.19 ± 27.62 | 29.25 ± 7.92 | 0.046 |

| Resp | 196.50 ± 71.66 | 207.53 ± 28.82 | 0.735 |

| pH | 5.92 ± 0.24 | 5.72 ± 0.15 | 0.282 |

| % Sand | 69.28 ± 4.85 | 69.26 ± 2.48 | 0.998 |

| % Silt | 21.20 ± 3.92 | 20.15 ± 2.06 | 0.951 |

| % Clay | 9.51 ± 1.32 | 10.58 ± 1.02 | 0.43 |

| BD | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 2.6 ± 0.9 | 0.761 |

| Diseased Plant | Healthy Plant | Mann–Whitney | |

| Metric | Bulk Soil | Bulk Soil | p Value |

| TN | 88.01 ± 9.51 | 55.67 ± 7.84 | 0.0001 |

| TOC | 1064.83 ± 80.90 | 753.33 ± 118.21 | 0.0003 |

| NH4 | 10.03 ± 4.64 | 3.20 ± 2.40 | 0.0009 |

| NO3 | 89.70 ± 28.80 | 22.15 ± 6.03 | 0.0001 |

| Resp | 278.70 ± 51.35 | 237.52 ± 75.58 | 0.2952 |

| pH | 6.05 ± 0.22 | 5.89 ± 0.19 | 0.207 |

| % Sand | 78.82 ± 4.29 | 81.62 ± 3.32 | 0.592 |

| % Silt | 11.48 ± 3.67 | 14.88 ± 3.64 | 0.235 |

| % Clay | 6.31 ± 1.24 | 6.91 ± 1.32 | 0.843 |

| BD | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 0.07 | 0.761 |

| ANOSIM Results | Total Bacteria | Bacterial Pathogens | Total Fungi | Fungal Pathogens | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global test results | R = 0.373, p = 0.0002 | R = 0.366, p = 0.0003 | R = 0.347, p = 0.002 | R = 0.323, p = 0.0001 | ||||

| Pairwise comparisons | R Stat | p Value | R Stat | p Value | R Stat | p Value | R Stat | p Value |

| Healthy vs diseased plant root soils | 0.566 | 0.003 | 0.563 | 0.004 | 0.752 | 0.004 | 0.554 | 0.002 |

| Healthy vs diseased plant bulk soils | 0.419 | 0.0002 | 0.485 | 0.002 | 0.046 | 0.273 | 0.231 | 0.05 |

| CAP Results | Total Bacteria | Bacterial Pathogens | Total Fungi | Fungal Pathogens | ||||

| Comparisons | CAP R2 | p Value | CAP R2 | p Value | CAP R2 | p Value | CAP R2 | p Value |

| Healthy vs diseased plant root soils | 0.788 | 0.0001 | 0.876 | 0.0002 | 0.801 | 0.0022 | 0.855 | 0.0008 |

| Healthy vs diseased plant bulk soils | 0.706 | 0.0001 | 0.723 | 0.0002 | 0.223 | 0.0022 | 0.599 | 0.008 |

| Total Bacteria | Bacterial Pathogens | Total Fungi | Fungal Pathogens | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diversity Index Comparisons | Richness | Diversity | Richness | Diversity | Richness | Diversity | Richness | Diversity |

| Healthy plant root soils | 330 ± 113 | 5.64 ± 0.28 | 14.50 ± 3.79 | 2.51 ± 0.23 | 23.51 ± 23.52 | 2.74 ± 0.71 | 8.51 ± 7.58 | 1.76 ± 0.80 |

| Diseased plant root soils | 335 ± 129 | 5.54 ± 0.43 | 14.15 ± 4.03 | 2.54 ± 0.24 | 86.83 ± 19.56 | 4.26 ± 0.26 | 20.17 ± 3.87 | 2.77 ± 0.21 |

| Mann–Whitney p value | 0.468 | 0.639 | 0.871 | 0.774 | 0.0002 | 0.0003 | 0.004 | 0.005 |

| Healthy plant bulk soil | 322 ± 57 | 5.67 ± 0.16 | 14.33 ± 2.58 | 2.58 ± 0.17 | 42.67 ± 24.29 | 3.44 ± 0.66 | 15.50 ± 7.69 | 2.44 ± 0.61 |

| Diseased plant bulk soil | 308 ± 132 | 5.51 ± 0.42 | 14.57 ± 4.40 | 2.55 ± 0.29 | 59.67 ± 36.39 | 3.72 ± 0.73 | 13.17 ± 5.60 | 2.40 ± 0.43 |

| Mann–Whitney p value | 0.813 | 0.404 | 0.911 | 0.827 | 0.262 | 0.502 | 0.571 | 0.898 |

| % MPS Diseased | % MPS Healthy | M-W | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Taxa | Function | Plant Bulk Soil | Plant Bulk Soil | p Value |

| Clostridium | CCD, N-Fix, AMO, possible plant pathogen | 3.50 ± 2.82 | 0.74 ± 0.78 | 0.001 * |

| Udaeobacter | Probable CCD | 3.45 ± 1.62 | 6.19 ± 1.98 | 0.005 * |

| Gemmata | Probable CCD | 3.42 ± 0.87 | 4.80 ±1.77 | 0.029 * |

| Pseudolabrys | CCD | 3.22 ± 1.54 | 0.94 ± 0.92 | 0.003 * |

| Solibacter | CCD | 3.20 ± 1.74 | 6.52 ± 3.40 | 0.105 |

| Pedomicrobium | CCD | 3.09 ± 1.15 | 0.68 ± 0.20 | 0.001 * |

| Vicinamibacter | CCD | 2.65 ± 0.87 | 1.27 ± 1.10 | 0.015 * |

| Bradyrhizobium | CCD, N-Fix, AMO | 2.37 ± 0.55 | 2.28 ± 0.83 | 0.355 |

| Bacillus | CCD, N-Fix, AMO, possible plant pathogen | 1.84 ± 0.94 | 2.73 ± 1.21 | 0.015 * |

| Methyloligella | Methylotrophs | 1.81 ± 0.73 | 0.56 ± 0.60 | 0.004 * |

| Rokubacteriales | Unclear | 1.70 ± 0.67 | 0.44 ± 0.46 | 0.002 * |

| Blastocatellia | CCD | 1.55 ± 1.20 | 0.22 ± 0.08 | 0.001 * |

| Acidobacteria (subgroup 2) | CCD | 1.51 ±2.35 | 6.38 ± 3.45 | 0.003 * |

| Mycobacterium | CCD | 1.51 ± 0.56 | 0.42 ± 0.29 | 0.001 * |

| Gaiella | CCD | 1.45 ± 0.67 | 0.48 ± 0.76 | 0.015 * |

| Nitrospira | AMO | 1.45 ± 0.66 | 1.15 ± 0.36 | 0.105 |

| Pirellula | AMO | 1.28 ± 0.54 | 0.33 ± 0.51 | 0.002 * |

| Reyranella | Unclear | 1.22 ± 0.53 | 0.40 ± 0.38 | 0.003 * |

| Actinobacteria | CCD | 1.13 ± 0.54 | 0.11 ± 0.17 | 0.001 * |

| Xiphinematobacter | Unclear | 1.11 ± 0.92 | 3.05 ± 1.30 | 0.001 * |

| Solirubrobacter | Unclear | 1.10 ± 0.49 | 0.17 ± 0.29 | 0.001 * |

| % MPS Diseased | % MPS Healthy | M-W | ||

| Bacterial Taxa | Function | Plant Root Soil | Plant Root Soil | p Value |

| Xanthobacter | CCD | 8.03 ± 4.10 | 6.77 ± 0.57 | 0.628 |

| Flavobacterium | CCD | 6.80 ± 13.04 | 4.67 ± 1.78 | 0.138 |

| Udaeobacter | Probable CCD | 4.76 ± 3.19 | 4.01 ±1.81 | 1 |

| Solibacter | CCD | 4.65 ± 3.88 | 1.86 ± 0.36 | 0.731 |

| Acidobacteria (Subgroup 2) | CCD | 4.26 ± 3.72 | 1.79 ± 0.83 | 0.534 |

| Gemmata | Probable CCD | 3.27 ± 2.32 | 3.66 ± 1.32 | 1 |

| Clostridium | CCD, N-Fix, AMO, plant pathogen | 3.18 ± 2.82 | 0.36 ± 0.38 | 0.019 * |

| Bacillus | CCD, N-Fix, AMO, plant pathogen | 2.73 ± 0.61 | 2.31 ± 1.27 | 0.945 |

| Acidobacteria | CCD | 2.64 ± 1.83 | 2.08± 0.40 | 0.628 |

| Rhizobium | CCD, N-Fix, AMO | 2.39 ± 2.72 | 0.0.33 ± 0.07 | 0.731 |

| Bradyrhizobium | CCD, N-Fix, AMO | 2.31 ± 0.65 | 2.86 ± 0.61 | 0.181 |

| Xiphinematobacter | Unclear | 2.89 ± 2.00 | 1.59 ± 0.57 | 0.775 |

| Ktedonobacter | Unclear | 1.94 ± 1.78 | 0.28 ± 0.18 | 0.153 |

| Elsterales | Unclear | 1.81 ± 1.80 | 0.74 ± 0.75 | 0.836 |

| Bryobacter | CCD | 1.79 ± 1.24 | 0.87 ± 0.23 | 0.253 |

| Acidibacter | Unclear | 1.33 ± 0.65 | 0.83 ± 0.31 | 0.138 |

| Acidothermus | CCD | 1.18 ± 0.72 | 1.00 ± 0.26 | 0.295 |

| Nitrospira | AMO | 1.18 ± 0.45 | 1.00 ± 0.27 | 0.181 |

| Burkholderia | CCD, N-Fix, AMO, plant pathogen | 1.11 ± 0.92 | 3.05 ± 1.30 | 0.008 * |

| % MPS Diseased | % MPS Healthy | M-W | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fungal Taxa | Function | Plant Bulk Soil | Plant Bulk Soil | p Value |

| Apiotrichum | CCD | 45.28 ± 29.11 | 48.26 ± 29.96 | 0.3367 |

| Rozella | Fungal, Oomycete, algae parasite | 4.17 ± 6.96 | 0.88 ± 0.91 | 0.259 |

| Mycosphaerella | Plant pathogen | 3.71 ± 2.82 | 4.93 ± 4.32 | 0.7478 |

| Saitozyma | CCD | 10.09 ± 26.88 | 3.15 ± 4.79 | 0.0782 |

| Glomus | ARM | 1.54 ± 3.13 | 2.88 ± 3.71 | 0.1488 |

| Dactylonectria | Plant pathogen | 3.77 ± 8.39 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.4418 |

| Ilyonectria | Plant pathogen | 1.28 ± 0.84 | 8.68 ± 5.16 | 0.0039 * |

| Monochaetia | Plant pathogen | 1.03 ± 2.52 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.3173 |

| % MPS Diseased | % MPS Healthy | M-W | ||

| Fungal Taxa | Function | Plant Root Soil | Plant Root Soil | p Value |

| Apiotrichum | CCD | 26.58 ± 9.52 | 62.07 ± 19.02 | 0.0163 * |

| Rozella | Fungal, Oomycete, algae parasite | 13.30 ± 7.22 | 0.65 ± 0.75 | 0.0038 * |

| Mycosphaerella | Plant pathogen | 11.65 ± 4.64 | 3.20 ± 1.84 | 0.0039 * |

| Archaeorhizomyces | Plant root-associated | 11.26 ± 6.54 | 0.23 ± 0.50 | 0.0033 * |

| Saitozyma | CCD | 5.17 ± 5.03 | 9.74 ± 5.00 | 0.0781 |

| Dipodascus | Plant pathogen | 2.76 ± 4.66 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.0021 * |

| Didymella | Plant pathogen | 2.37 ± 2.25 | 0.09 ± 0.21 | 0.0028 * |

| Acrocalymma | Plant pathogen | 1.97 ± 1.59 | 0.37 ± 0.66 | 0.0225 * |

| Glomus | ARM | 1.48 ± 1.16 | 3.00 ± 1.89 | 0.1093 |

| Tremella | CCD, fungal parasite | 1.01 ± 1.54 | 0.06 ± 0.15 | 0.0493 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eaton, W.D.; Hamilton, D.A.; Lemenze, A.; Soteropoulos, P. Initial Analysis of Plant Soil for Evidence of Pathogens Associated with a Disease of Seedling Ocotea monteverdensis. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1682. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13071682

Eaton WD, Hamilton DA, Lemenze A, Soteropoulos P. Initial Analysis of Plant Soil for Evidence of Pathogens Associated with a Disease of Seedling Ocotea monteverdensis. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(7):1682. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13071682

Chicago/Turabian StyleEaton, William D., Debra A. Hamilton, Alexander Lemenze, and Patricia Soteropoulos. 2025. "Initial Analysis of Plant Soil for Evidence of Pathogens Associated with a Disease of Seedling Ocotea monteverdensis" Microorganisms 13, no. 7: 1682. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13071682

APA StyleEaton, W. D., Hamilton, D. A., Lemenze, A., & Soteropoulos, P. (2025). Initial Analysis of Plant Soil for Evidence of Pathogens Associated with a Disease of Seedling Ocotea monteverdensis. Microorganisms, 13(7), 1682. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13071682