Occurrence and Monitoring of the Zoonotic Pathogen Yersinia pseudotuberculosis in Various Zoo Animal Species

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection at the Wilhelma Zoo and the Opel Zoo

2.2. Microbiological Examination of the Samples

2.3. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Collection of Y. pseudotuberculosis Cases from Other Zoos

3. Results

3.1. Data from the Monitoring of the Wilhelma and the Opel Zoo

Descriptive and Statistical Analysis

3.2. Occurrence of Pseudotuberculosis in Mammals from All the 19 Zoos and the Private Keeping Included in This Study

3.2.1. Rodents

3.2.2. Primates

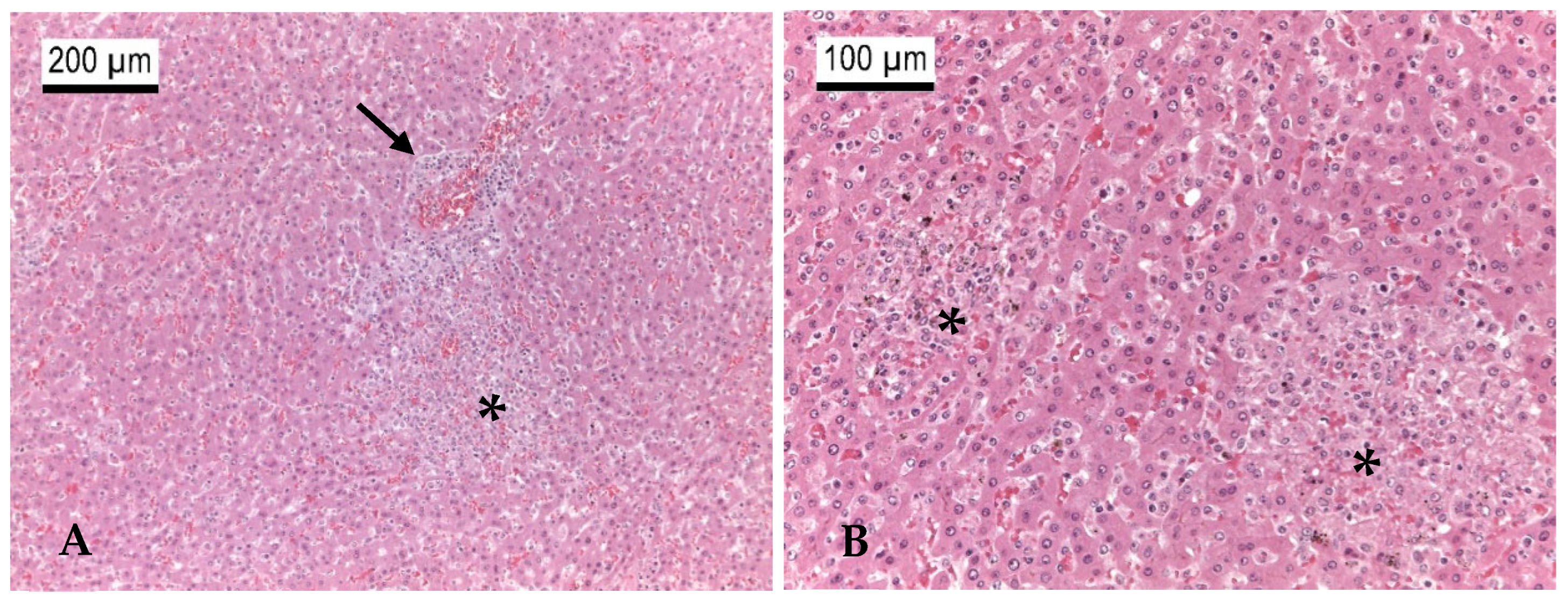

3.2.3. Ruminants

| Case No. | Species | Year | Month | Pathology | Source of Y. pseudotuberculosis | Zoo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ru1 | African dwarf goat Capra aegagrus hircus | 2015 | March | Liver multifocal and spleen with focal acute purulent-necrotizing inflammation, severe acute necrotizing ileitis and colitis | Intestine, mesenteric lymph nodes, spleen, liver, lungs | Kronberg |

| Ru2 | Alpine ibex Capra ibex | 2024 | April | Multifocal necrotizing placentitis | Amniotic sac, stomach, liver, lungs, kidney of the fetus | Nuremberg |

| Ru3 | Alpine ibex Capra ibex | 2024 | April | Abortion | Feces | Nuremberg |

| Ru4 | Bactrian deer Cervus hanglu bactrianus | 2020 | December | Liver multifocal single cell necrosis, low-grade acute multifocal erosive-necrotizing ruminitis with intralesional bacteria, chronic multifocal purulent-necrotizing stomatitis, external ear with severe chronic purulent-necrotizing dermatitis | Liver, spleen, mucous membranes of the mouth | Kronberg |

| Ru5 | Blackbuck Antilope cervicapra | 2018 | April | Purulent-necrotizing inflammation in the lungs, liver, intestines, lymph nodes and in the navel area, bacterial foci in the spleen, hyperemia in the brain | Liver, lungs, spleen, kidney | Kronberg |

| Ru6 | Blackbuck Antilope cervicapra | 2022 | November | Multifocal, acute purulent-necrotizing inflammations with bacterial foci in the liver, spleen, kidneys, intestine, mesenteric lymph nodes, heart, and muscles; parasitosis with coccidia | Intestine | Kronberg |

| Ru7 | Blackbuck Antilope cervicapra | 2023 | February | Multifocal necrotizing hepatitis, lymphadenitis, and catarrhal enteritis | Spleen, kidney, lungs, bone marrow | Kronberg |

| Ru8 | Blackbuck Antilope cervicapra | 2018 | January | Multifocal necrotizing hepatitis and nephritis | Liver, lungs, kidneys, brain, intestine | Karlsruhe |

| Ru9 | Blackbuck Antilope cervicapra | 2020 | March | Acute purulent-necrotizing hepatitis and pneumonia | Liver, lungs, leptomeninx, myocardium | Karlsruhe |

| Ru10 | Blackbuck Antilope cervicapra | 2021 | February | Multifocal purulent-necrotizing pneumonia and hepatitis; high-grade embolic-purulent focal nephritis | Liver, lungs, kidney | Karlsruhe |

| Ru11 | Blackbuck Antilope cervicapra | 2023 | January | Acute purulent-necrotizing hepatitis, pneumonia and enteritis | Liver, lungs, intestine | Karlsruhe |

| Ru12 | Blackbuck Antilope cervicapra | 2023 | February | Diptheroid-necrotizing enteritis, parasitosis with gastrointestinal strongylids | Lungs, intestine | Karlsruhe |

| Ru13 | Fallow deer Dama dama | 2021 | February | Acute diffuse fibrinous-necrotizing enterocolitis, acute multifocal purulent-necrotizing lymphadenitis of the mesenteric lymph nodes | Intestine, mesenteric lymph nodes, feces | Zurich |

| Ru14 | Impala Aepyceros melampus | 2018 | January | Brain, lungs, lymph nodes, heart, spleen, liver, kidney, pancreas, intestine with moderate to severe multifocal embolic and purulent partly necrotizing inflammation | Liver, spleen, kidney, lungs, intestine, brain | Kronberg |

| Ru15 | Impala Aepyceros melampus | 2022 | November | Purulent-necrotizing hepatitis and enteritis, lymph node hyperplasia | Liver, spleen, kidney, lungs, intestine, lymph nodes | Kronberg |

| Ru16 | Impala Aepyceros melampus | 2023 | December | Necrotizing enteritis and lymphadenitis, darkening of the liver parenchyma | Liver, spleen, kidney, lungs, mesenteric lymph nodes, bone marrow, abdominal cavity | Kronberg |

| Ru17 | Impala Aepyceros melampus | 2024 | January | Purulent-abscessed lymphadenitis, acute catarrhal enteritis, pneumonia, white foci in the kidney | Intestine | Kronberg |

| Ru18 | Impala Aepyceros melampus | 2020 | February | Acute catarrhal-purulent inflammation with necrosis in the liver, lungs, spleen, intestines; mesenteric lymph nodes | Intestine | Kronberg |

| Ru19 | Markhor Capra falconeri | 2015 | n.a. 1 | Catarrhal enteritis, parasitosis with coccidia | Intestine | Berlin |

| Ru20 | Mesopotamian fallow deer Dama mesopotamica | 2020 | December | Acute purulent inflammation with necrosis in the liver, lungs, kidneys, spleen, intestines, lymph nodes | Liver, lungs, spleen, kidney | Kronberg |

| Ru21 | Mhorr’s gazelle Nanger dama mhorr | 2011 | n.a. 1 | Purulent-necrotizing mastitis, splenic hyperplasia and splenomegaly, liver with multiple white foci, purulent endometritis | Liver, spleen, udder, uterus | Berlin |

| Ru22 | Pudu Pudu puda | 2019 | April | Generalized swelling of the lymph nodes, multifocal purulent-necrotizing hepatitis | Liver, lungs, spleen | Wuppertal |

| Ru23 | Pudu Pudu puda | 2019 | January | Enterocolitis | Intestine | Wuppertal |

| Ru24 | Reindeer Rangifer tarandus | 2021 | September | Multifocal acute purulent hepatitis and pneumonia, mesenteric lymph nodes with bacterial foci, pyloric stenosis of the abomasum, hemosiderosis of the spleen | Liver, lungs, spleen, kidney | Wuppertal |

| Ru25 | White-lipped deer Cervus albirostris | 2024 | April | Stillbirth still attached to placenta, advanced stage of autolysis | Liver of the fetus | Berlin |

3.2.4. Other Mammal Species

Carnivora

Diprotodontia

Hyracoidea

Macroscelidea

3.3. Occurrence of Pseudotuberculosis in Birds from All the 19 Zoos Included in This Study

3.4. Antimicrobial Susceptibility

4. Discussion

4.1. Y. pseudotuberculosis Infections in Zoo Animals

4.2. Y. pseudotuberculosis in Free-Living Animals

4.3. Preventive Measures

4.4. Antimicrobials

4.5. Seasonal Occurrence of Y. pseudotuberculosis Infections

4.6. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mair, N.S. Yersiniosis in wildlife and its public health implications. J. Wildl. Dis. 1973, 9, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, S.; Hayashidani, H.; Sotohira, Y.; Une, Y. Yersiniosis caused by Yersinia pseudotuberculosis in captive toucans (Ramphastidae) and a Japanese squirrel (Sciurus lis) in zoological gardens in Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2016, 78, 297–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammerl, J.A.; Barac, A.; Bienert, A.; Demir, A.; Drüke, N.; Jäckel, C.; Matthies, N.; Jun, J.W.; Skurnik, M.; Ulrich, J.; et al. Birds kept in the German zoo “Tierpark Berlin” are a common source for polyvalent Yersinia pseudotuberculosis phages. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 634289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubbert, W.T. Yersiniosis in mammals and birds in the United States: Case reports and review. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1972, 21, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinhardt, M.; Hammerl, J.A.; Kunz, K.; Barac, A.; Nöckler, K.; Hertwig, S. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis prevalence and diversity in wild boars in Northeast Germany. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e00675-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleksić, S.; Bockemühl, J. Microbiology and epidemiology of Yersinia infections. Immun. Infekt. 1990, 18, 178–185. [Google Scholar]

- Platt-Samoraj, A.; Żmudzki, J.; Pajdak-Czaus, J.; Szczerba-Turek, A.; Bancerz-Kisiel, A.; Procajło, Z.; Łabuć, S.; Szweda, W. The prevalence of Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis in small wild rodents in Poland. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2020, 20, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamm, I.; Hailer, M.; Depner, B.; Kopp, P.A.; Rau, J. Yersinia enterocolitica in diagnostic fecal samples from European dogs and cats: Identification by fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 887–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, C.L.; Napier, J.E.; Armstrong, D.L.; Gladney, L.M.; Tarr, C.L.; Freeman, M.M.; Iwen, P.C. Clonal spread of Yersinia enterocolitica 1B/O:8 in multiple zoo species. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2020, 51, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosario-Acevedo, R.; Biryukov, S.S.; Bozue, J.A.; Cote, C.K. Plague prevention and therapy: Perspectives on current and future strategies. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, C.L.; Rosenzweig, J.A.; Kirtley, M.L.; Chopra, A.K. Pathogenesis of Y. enterocolitica and Y. pseudotuberculosis in human yersiniosis. J. Pathog. 2011, 2011, 182051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomaso, H.; Mooseder, G.; Al Dahouk, S.; Bartling, C.; Scholz, H.C.; Strauss, R.; Treu, T.M.; Neubauer, H. Seroprevalence of anti-Yersinia antibodies in healthy Austrians. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2006, 21, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakata, N.; Nishioka, H. Strawberry tongue in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection. QJM 2023, 116, 447–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert Koch Institute. SurvStat@RKI 2.0; Robert Koch Institute: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Koch Institute. RKI Guide for Infectious Diseases; RKI-Guide: Union City, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Magistrali, C.F.; Cucco, L.; Pezzotti, G.; Farneti, S.; Cambiotti, V.; Catania, S.; Prati, P.; Fabbi, M.; Lollai, S.; Mangili, P.; et al. Characterisation of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis isolated from animals with yersiniosis during 1996-2013 indicates the presence of pathogenic and Far Eastern strains in Italy. Vet. Microbiol. 2015, 180, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Guern, A.S.; Martin, L.; Savin, C.; Carniel, E. Yersiniosis in France: Overview and potential sources of infection. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 46, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksson-Ahomaa, M.W.S. Enteropathogenic Yersinia: Pathogenicity, Disease, Diagnostics and Preventive Measures; Behr’s GmbH: Hamburg-Nord, Germany, 2019; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, S.; Bingham, W.; Wilson, F. Fatal yersiniosis in farmed deer caused by Yersinia pseudotuberculosis serotype O:3 encoding a mannosyltransferase-like protein WbyK. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2008, 20, 356–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, S.; Perl, S. Outbreak of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis in a zoo in Israel. Isr. J. Vet. Med. 2023, 78, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Ceccolini, M.E.; Macgregor, S.K.; Spiro, S.; Irving, J.; Hedley, J.; Williams, J.; Guthrie, A. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infections in primates, artiodactyls, and birds within a zoological facility in the United Kingdom. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2020, 51, 527–538, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.; Gibbons, J.; Harris, J.D.; Taylor, C.S.; Scott, C.; Paterson, G.K.; Morrison, L.R. Systemic Yersinia pseudotuberculosis as a cause of osteomyelitis in a captive ring-tailed Lemur (Lemur catta). J. Comp. Pathol. 2018, 164, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, K.; Veiga, I.B.; Schediwy, M.; Wiederkehr, D.; Meniri, M.; Schneeberger, M.; den Broek, P.R.; Gurtner, C.; Fasel, N.J.; Kittl, S.; et al. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis serotype O:1 infection in a captive Seba’s short tailed-fruit bat (Carollia perspicillata) colony in Switzerland. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, J.; Eisenberg, T.; Männig, A.; Wind, C.; Lasch, P.; Sting, R. MALDI-UP—An inter-net platform for the exchange of mass spectra—User guide for http://maldi-up.ua-bw.de/. Asp. Food Control. Anim. Health 2016, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Rau, J.; Etter, D.; Frentzel, H.; Lasch, P.; Contzen, M. Reliable delineation of Bacillus cytotoxicus from other members of the Bacillus cereus group by MALDI-TOF MS—An extensive validation study. Food Control 2024, 167, 110825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, J.; Eisenberg, T.; Wind, C.; Huber, I.; Pavlovic, M.; Becker, R. Guidelines for vali-dating species identifications using ma-trix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) in a single laboratory or in laboratory networks. J. Cons. Prot. Food Saf. 2022, 17, 97–101. Available online: https://www.jidc.org/index.php/journal/article/download/32074095/2131 (accessed on 15 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. CLSI M100 Performance Standards for Antimircobial Susceptibility Testing, 31st ed.; CLSI Supplement M100: Wayne, PA, USA, 2021; Volume 31. [Google Scholar]

- Fogelson, S.B.; Yau, W.; Rissi, D.R. Disseminated Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection in a paca (Cuniculus paca). J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2015, 46, 130–134, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cano-Terriza, D.; Beato-Benítez, A.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, B.; Agulló-Ros, I.; Guerra, R.; Jiménez-Martín, D.; Barbero-Moyano, J.; García-Bocanegra, I. Outbreak of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis in capybaras (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) kept in captivity. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2022, 86, 101811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, S.; Hayashidani, H.; Yonezawa, A.; Suzuki, I.; Une, Y. Yersiniosis due to infection by Yersinia pseudotuberculosis 4b in captive meerkats (Suricata suricatta) in Japan. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2015, 27, 641–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plesker, R.; Claros, M. A spontaneous Yersinia pseudotuberculosis-infection in a monkey-colony. Zentralbl Vet. B 1992, 39, 201–208. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, J.; Kondova, I.; de Groot, C.W.; Remarque, E.J.; Heidt, P.J. A report on Yersinia-related mortality in a colony of new world monkeys. ResearchGate 2007, 46, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, D.P.; Lerche, N.W.; Henrickson, R.V. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection in a group of Macaca fascicularis. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1980, 177, 818–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, J.A.; Wood, M. Yersiniosis in a breeding unit of Macaca fascicularis (cynomolgus monkeys). Lab. Anim. 1983, 17, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kageyama, T.; Ogasawara, A.; Fukuhara, R.; Narita, Y.; Miwa, N.; Kamanaka, Y.; Abe, M.; Kumazaki, K.; Maeda, N.; Suzuki, J.; et al. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection in breeding monkeys: Detection and analysis of strain diversity by PCR. J. Med. Primatol. 2002, 31, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, R.D.; Ely, R.W.; Holland, R.J. Epizootic of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis in a wildlife park. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1992, 201, 142–144. [Google Scholar]

- Buhles, W.C., Jr.; Vanderlip, J.E.; Russell, S.W.; Alexander, N.L. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection: Study of an epizootic in squirrel monkeys. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1981, 13, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, N.; Li, M.; Amer, S.; Liu, S.; Luo, J.; Wang, S.; He, H. Mortality in captive Rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) in China due to infection with Yersinia pseudotuberculosis serotype O:1a. Ecohealth 2016, 13, 597–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seimiya, Y.M.; Sasaki, K.; Satoh, C.; Takahashi, M.; Yaegashi, G.; Iwane, H. Caprine enteritis associated with Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2005, 67, 887–890. [Google Scholar]

- Giannitti, F.; Barr, B.C.; Brito, B.P.; Uzal, F.A.; Villanueva, M.; Anderson, M. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infections in goats and other animals diagnosed at the California Animal Health and Food Safety Laboratory System: 1990–2012. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2014, 26, 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, J.R.; Behravesh, C.B.; Angulo, F.J. Diseases transmitted by domestic livestock: Perils of the petting zoo. Microbiol. Spectr. 2015, 3, 10–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, C.C.; Stanford, K.; Narvaez-Bravo, C.; Callaway, T.; McAllister, T. Farm fairs and petting zoos: A review of animal contact as a source of zoonotic enteric disease. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2017, 14, 59–73. [Google Scholar]

- Isler, M.; Wissmann, R.; Morach, M.; Zurfluh, K.; Stephan, R.; Nüesch-Inderbinen, M. Animal petting zoos as sources of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli, Salmonella and extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Zoonoses Public Health 2021, 68, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karbe, E.; Erickson, E.D. Ovine abortion and stillbirth due to purulent placentitis caused by Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Vet. Pathol. 1984, 21, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otter, A. Ovine abortion caused by Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Vet. Rec. 1996, 138, 143–144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peel, M. Clinical and pathologic presentations of yersiniosis in various nondomestic species: An investigation of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis outbreaks from four North American zoological institutions. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2024, 55, 1095–1103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- van den Brom, R.; Lievaart-Peterson, K.; Luttikholt, S.; Peperkamp, K.; Wouda, W.; Vellema, P. Abortion in small ruminants in the Netherlands between 2006 and 2011. Tijdschr Diergeneeskd. 2012, 137, 450–457. [Google Scholar]

- Hannam, D.A. Bovine abortion associated with Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Vet. Rec. 1993, 133, 372. [Google Scholar]

- Jerrett, I.V.; Slee, K.J. Bovine abortion associated with Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection. Vet. Pathol. 1989, 26, 181–183. [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka, Y.; Okada, Y.; Makino, S.; Maruyama, T. Isolation of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis from city-living crows captured in a zoo. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1994, 56, 785–786. [Google Scholar]

- Galosi, L.; Farneti, S.; Rossi, G.; Cork, S.C.; Ferraro, S.; Magi, G.E.; Petrini, S.; Valiani, A.; Cuteri, V.; Attili, A.R. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, serogroup O:1A, infection in two amazon parrots (Amazona aestiva and amazona oratrix) with hepatic hemosiderosis. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2015, 46, 588–591. [Google Scholar]

- Shopland, S.; Barbon, A.R.; Cotton, S.; Whitford, H.; Barrows, M. Retrospective review of mortality in captive pink pigeons (Nesoenas mayeri) housed in European collections: 1977–2018. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2020, 51, 159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Stoute, S.T.; Cooper, G.L.; Bickford, A.A.; Carnaccini, S.; Shivaprasad, H.L.; Sentíes-Cué, C.G. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis in Eurasian collared doves (Streptopelia decaocto) and retrospective study of avian yersiniosis at the California animal health and food safety laboratory system (1990–2015). Avian Dis. 2016, 60, 82–86. [Google Scholar]

- Körmendy, B.; Illés, J.; Glávits, R.; Sztojkov, V. An outbreak of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection in a bustard (Otis tarda) flock. Acta Vet. Hung. 1988, 36, 173–176. [Google Scholar]

- Cabot, M.L.; Negrao Watanabe, T.T.; Womble, M.; Harrison, T.M. Yersinia Pseudotuberculosis infection in lions (Panthera leo) at a zoological park. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2022, 53, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Childs-Sanford, S.E.; Kollias, G.V.; Abou-Madi, N.; McDonough, P.L.; Garner, M.M.; Mohammed, H.O. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis in a closed colony of Egyptian fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus). J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2009, 40, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baskin, G.B.; Montali, R.J.; Bush, M.; Quan, T.J.; Smith, E. Yersiniosis in captive exotic mammals. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1977, 171, 908–912. [Google Scholar]

- Balada-Llasat, J.M.; Panilaitis, B.; Kaplan, D.; Mecsas, J. Oral inoculation with Type III secretion mutants of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis provides protection from oral, intraperitoneal, or intranasal challenge with virulent Yersinia. Vaccine 2007, 25, 1526–1533. [Google Scholar]

- Bliska, J.B.; Brodsky, I.E.; Mecsas, J. Role of the Yersinia pseudotuberculosis virulence plasmid in pathogen-phagocyte interactions in mesenteric lymph nodes. EcoSal Plus 2021, 9, eESP00142021. [Google Scholar]

- Stanger, K.J.; McGregor, H.; Larsen, J. Outbreaks of diarrhoea (‘winter scours’) in weaned Merino sheep in south-eastern Australia. Aust. Vet. J. 2018, 96, 176–183. [Google Scholar]

- Hammerl, J.A.; Vom Ort, N.; Barac, A.; Jackel, C.; Grund, L.; Dreyer, S.; Heydel, C.; Kuczka, A.; Peters, H.; Hertwig, S. Analysis of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis isolates recovered from deceased mammals of a German zoo animal collection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2021, 59, e03125-20. [Google Scholar]

- Stanger, K.J.; McGregor, H.; Marenda, M.; Morton, J.M.; Larsen, J.W.A. A longitudinal study of faecal shedding of Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis by Merino lambs in south-eastern Australia. Prev. Vet. Med. 2018, 153, 30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Joutsen, S.; Laukkanen-Ninios, R.; Henttonen, H.; Niemimaa, J.; Voutilainen, L.; Kallio, E.R.; Helle, H.; Korkeala, H.; Fredriksson-Ahomaa, M. Yersinia spp. in wild rodents and shrews in Finland. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2017, 17, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Chavarría, L.C.; Vadyvaloo, V. Yersinia pestis and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection: A regulatory RNA perspective. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 956. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Montañez, J.; Benavides-Montaño, J.A.; Hinz, A.K.; Vadyvaloo, V. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis IP32953 survives and replicates in trophozoites and persists in cysts of Acanthamoeba castellanii. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2015, 362, fnv091. [Google Scholar]

- Amphlett, A. Far East scarlet-like fever: A review of the epidemiology, symptomatology, and role of superantigenic toxin: Yersinia pseudotuberculosis-derived mitogen A. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2016, 3, ofv202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, J.R. Importance of a One Health approach in advancing global health security and the sustainable development goals. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2019, 38, 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Zinsstag, J.; Crump, L.; Winkler, M. Biological threats from a ‘One Health’ perspective. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2017, 36, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cardoen, S.; De Clercq, K.; Vanholme, L.; De Winter, P.; Thiry, E.; Van Huffel, X. Preparedness activities and research needs in addressing emerging infectious animal and zoonotic diseases. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2017, 36, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- CleanLink. 5 Ways Handwashing Changed Since the Pandemic. Available online: https://www.cleanlink.com/news/article/5-Ways-Handwashing-Changed-Since-the-Pandemic--30874 (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- Lauterbach, S.E.; Nelson, S.W.; Martin, A.M.; Spurck, M.M.; Mathys, D.A.; Mollenkopf, D.F.; Nolting, J.M.; Wittum, T.E.; Bowman, A.S. Adoption of recommended hand hygiene practices to limit zoonotic disease transmission at agricultural fairs. Prev. Vet. Med. 2020, 182, 105116. [Google Scholar]

- Compendium of measures to prevent disease associated with animals in public settings, 2013. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2013, 243, 1270–1288.

- American Association of Zoo Veterinarians (AAZV). The Infectious Disease Committee of the American Association of Zoo Veterinarians (AAZV) Publishes Infectious Diseases of Concern to Captive and Free-Ranging Wildlife in North America. One Health Initiative. 2011. Available online: https://onehealthinitiative.com/publication/the-infectious-disease-committee-of-the-american-association-of-zoo-veterinarians-aazv-publishes-infectious-diseases-of-concern-to-captive-and-free-ranging-wildlife-in-north-america/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- European Parliament. Regulation (EU) 2019/6 OF the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on Veterinary Medicinal Products and Repealing Directive 2001/82/EC; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Stanger, K.J.; McGregor, H.; Marenda, M.; Morton, J.M.; Larsen, J. Assessment of the efficacy of an autogenous vaccine against Yersinia pseudotuberculosis in young Merino sheep. N. Z. Vet. J. 2019, 67, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Quintard, B.; Petit, T.; Ruvoen, N.; Carniel, E.; Demeure, C.E. Efficacy of an oral live vaccine for veterinary use against pseudotuberculosis. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2010, 33, e59–e65. [Google Scholar]

- González-Juarbe, N.; Shen, H.; Bergman, M.A.; Orihuela, C.J.; Dube, P.H. YopE specific CD8+ T cells provide protection against systemic and mucosal Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172314. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, C.; Sebbane, F.; Poiret, S.; Goudercourt, D.; Dewulf, J.; Mullet, C.; Simonet, M.; Pot, B. Protection against Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection conferred by a Lactococcus lactis mucosal delivery vector secreting LcrV. Vaccine 2009, 27, 1141–1144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bonardi, S.; Bruini, I.; D’Incau, M.; Van Damme, I.; Carniel, E.; Brémont, S.; Cavallini, P.; Tagliabue, S.; Brindani, F. Detection, seroprevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis in pig tonsils in northern Italy. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 235, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Foligne, B.; Dessein, R.; Marceau, M.; Poiret, S.; Chamaillard, M.; Pot, B.; Simonet, M.; Daniel, C. Prevention and treatment of colitis with Lactococcus lactis secreting the immunomodulatory Yersinia LcrV protein. Gastroenterology 2007, 133, 862–874. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Branger, C.G.; Torres-Escobar, A.; Sun, W.; Perry, R.; Fetherston, J.; Roland, K.L.; Curtiss, R., 3rd. Oral vaccination with LcrV from Yersinia pestis KIM delivered by live attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium elicits a protective immune response against challenge with Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and Yersinia enterocolitica. Vaccine 2009, 27, 5363–5370. [Google Scholar]

- Först, G.; Giesen, R.; Fink, G.; Sehlbrede, M.; Wimmesberger, N.; Allen, R.; Meyer, K.; Müller, S.; Niese, H.; Polk, S.; et al. An in-depth analysis of antimicrobial prescription quality in 10 non-university hospitals, in southwest Germany, 2021. Eurosurveillance 2024, 29, 2400156. [Google Scholar]

- Pascale, R.; Giannella, M.; Bartoletti, M.; Viale, P.; Pea, F. Use of meropenem in treating carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections. Expert. Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2019, 17, 819–827. [Google Scholar]

- Bonke, R.; Wacheck, S.; Stüber, E.; Meyer, C.; Märtlbauer, E.; Fredriksson-Ahomaa, M. Antimicrobial susceptibility and distribution of β-lactamase A (blaA) and β-lactamase B (blaB) genes in enteropathogenic Yersinia species. Microb. Drug Resist. 2011, 17, 575–581. [Google Scholar]

- Iordanidis, P. A case of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection in canaries. J. Hell. Vet. Med. Soc. 2005, 56, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lemaitre, B.C.; Mazigh, D.A.; Scavizzi, M.R. Failure of beta-lactam antibiotics and marked efficacy of fluoroquinolones in treatment of murine Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1991, 35, 1785–1790. [Google Scholar]

- World Organisation for Animal Health. OIE List of Antimicrobial Agents of Veterinary Importance; World Organisation for Animal Health: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tufa, T.B.; Amenu, K.; Fasil, N.; Regassa, F.; Beyene, T.J.; Revie, C.W.; Hogeveen, H.; Stegeman, J.A. Prudent use and antimicrobial prescription practices in Ethiopian veterinary clinics located in different agroecological areas. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 538. [Google Scholar]

- Stegemann, M.; Trost, U. New developments in the fight against bacterial infections: Update on antiobiotic research, development and treatment. Inn. Med. 2023, 64, 1123–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Kageruka, P.; Mortelmans, J.; Vercruysse, J.; Beernaert-Declercq, C. Pseudotuberculosis in the Antwerp Zoo. Acta Zool. Pathol. Antverp. 1976, 66, 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Rouffaer, L.O.; Baert, K.; Van den Abeele, A.M.; Cox, I.; Vanantwerpen, G.; De Zutter, L.; Strubbe, D.; Vranckx, K.; Lens, L.; Haesebrouck, F.; et al. Low prevalence of human enteropathogenic Yersinia spp. in brown rats (Rattus norvegicus) in Flanders. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175648. [Google Scholar]

- Stĕrba, F. The incidence and seasonal dynamics of yersinioses (Y. pseudotuberculosis, Y. enterocolitica), staphylococcoses and pasteurelloses in hares from 1976 to 1982. Vet. Med. 1985, 30, 359–372. [Google Scholar]

- Keto-Timonen, R.; Pöntinen, A.; Aalto-Araneda, M.; Korkeala, H. Growth of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis strains at different temperatures, pH values, and NaCl and ethanol concentrations. J. Food Prot. 2018, 81, 142–149. [Google Scholar]

| Material | No. Samples (Wilhelma) | Positive | No. Samples (Opel Zoo) | Positive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fecal samples (sick animals) | 17 | - | 20 | - |

| Fecal samples (‘hotspot species’) | 108 | - | 61 | 1 |

| Fecal samples (clinically healthy animals with increased risk of infection) | 29 | - | 60 | 1 |

| Necropsies (zoo animals) | 148 | 2 | 18 | 3 |

| Carcasses (wild small mammals and birds found dead on the grounds of Wilhelma) | 311 | 6 | - | - |

| Total | 613 | 8 | 159 | 5 |

| Case No. | Species | Year | Month | Gross Pathological Findings | Source of Y. pseudotuberculosis Isolated | Zoo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | Brown rat Rattus norvegicus | 2024 | January | No organ abnormalities (pest control) | Liver, intestine | Stuttgart |

| R2 | Brown rat Rattus norvegicus | 2024 | February | No organ abnormalities (pest control) | Liver, intestine | Stuttgart |

| R3 | Brown rat Rattus norvegicus | 2024 | March | No organ abnormalities (pest control) | Liver, intestine | Stuttgart |

| R4 | Brown rat Rattus norvegicus | 2024 | March | No organ abnormalities (pest control) | Liver, intestine | Stuttgart |

| R5 | Capybara Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris | 2007 | n.a.1 | n.a. 1 | n.a. 1 | Stuttgart |

| R6 | Capybara Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris | 2019 | December | Multifocal necrotizing pneumonia, splenitis, hepatitis, and hyperplasia of mesenteric lymph nodes | Liver, spleen, lungs, kidney, intestine, lymph nodes | Schwerin |

| R7 | Capybara Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris | 2020 | January | Swollen liver and spleen, liver with blunt margins | Liver, spleen, lungs, heart | Schwerin |

| R8 | Capybara Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris | 2020 | January | Enteritis and necrotizing hepatitis | Liver, spleen, lungs, kidney, heart | Schwerin |

| R9 | Chacoan mara Dolichotis salinicola | 2019 | April | High-grade purulent-necrotizing hepatitis and splenitis with bacterial foci | Liver, spleen, kidney | Wuppertal |

| R10 | Chacoan mara Dolichotis salinicola | 2023 | March | High-grade necrotizing hepatitis, splenitis, enteritis, and pneumonia | Liver, spleen, lungs, kidney, intestine | Wuppertal |

| R11 | Eurasian red squirrel Sciurus vulgaris | 2024 | January | No organ abnormalities | Liver, intestine | Stuttgart |

| R12 | Guinea pig Cavia porcellus | 2008 | n.a. 1 | High-grade purulent-necrotizing hepatitis, splenitis, mesenteric lymphadenitis, and pneumonia | Spleen | Berlin |

| R13 | Guinea pig Cavia porcellus | 2015 | February | High-grade purulent-necrotizing hepatitis, splenitis, mesenteric lymphadenitis, and arthritis | Lymph nodes | Zurich |

| R14 | Indian crested porcupine Hystrix indica | 2023 | March | Epiphora | Conjunctiva | Frankfurt |

| R15 | Patagonian mara Dolichotis patagonum | 2015 | January | High-grade purulent-necrotizing hepatitis, nephritis, mesenteric lymphadenitis, and pneumonia | Liver, lungs, kidney, lymph nodes | Wuppertal |

| R16 | Patagonian mara Dolichotis patagonum | 2015 | January | High-grade purulent-necrotizing hepatitis, nephritis, splenitis, and pneumonia | Liver, spleen, lungs, kidney | Wuppertal |

| R17 | Patagonian mara Dolichotis patagonum | 2017 | August | Necrotizing multifocal hepatitis, mesenteric lymphadenitis, splenic hyperplasia, parasitosis with gastrointestinal nematodes | Liver, spleen, lungs, kidney, lymph nodes | Wuppertal |

| R18 | Patagonian mara Dolichotis patagonum | 2017 | December | High-grade purulent-necrotizing hepatitis and splenitis, parasitosis with gastrointestinal nematodes and coccidia | Liver, spleen | Wuppertal |

| R19 | Patagonian mara Dolichotis patagonum | 2017 | April | Abscess on shoulder, enteritis | Abscess | Wuppertal |

| R20 | Patagonian mara Dolichotis patagonum | 2017 | April | Abscesses in liver, spleen, and pelvis | Liver, abscess in pelvis | Wuppertal |

| R21 | Patagonian mara Dolichotis patagonum | 2017 | April | Necrotizing hepatitis, mesenteric lymphadenitis, spleen hyperplasia, high-grade purulent arthritis, and dermatitis on the hind limbs | Liver, spleen, lungs, kidney, intestine, arthritis | Wuppertal |

| R22 | Patagonian mara Dolichotis patagonum | 2020 | October | Necrotizing hepatitis, mesenteric lymphadenitis, enteritis, spleen hyperplasia, and hyperemia | Liver, spleen, lungs, kidney, lymph nodes | Wuppertal |

| R23 | Patagonian mara Dolichotis patagonum | 2020 | December | High-grade purulent-necrotizing pneumonia, hepatitis, splenitis, nephritis, lymphadenitis, parasitosis with coccidia | Liver, spleen, lungs, kidney, intestine | Wuppertal |

| Case No. | Species | Year | Month | Gross Pathological Findings | Source of Y. pseudotuberculosis Isolated | Zoo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Black-capped squirrel monkey Saimiri sciureus | 2019 | December | Necrotizing multifocal hepatitis, splenic hyperplasia with miliary-necrotizing inflammation, intestine with diphtheroid-necrotizing plaques | Liver, spleen, lungs, intestine | Stuttgart |

| P2 | Black-capped squirrel monkey Saimiri sciureus | 2024 | January | Multiple granulomas in the liver parenchyma and spleen, necrotizing enteritis | Liver, spleen, intestine | Hodenhagen |

| P3 | Black-capped squirrel monkey Saimiri sciureus | 2024 | January | Moderate multifocal necrotizing hepatitis, splenitis, and enteritis | Liver, spleen, intestine | Hodenhagen |

| P4 | Black spider monkey Ateles fusciceps rufiventris | 2018 | January | High-grade multifocal necrotizing inflammation of liver and spleen | Liver, spleen | Wuppertal |

| P5 | Black spider monkey Ateles fusciceps rufiventris | 2018 | January | High-grade hyperplasia of spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes | Liver, spleen, kidney | Wuppertal |

| P6 | Black spider monkey Ateles fusciceps rufiventris | 2018 | January | Feces | Feces | Wuppertal |

| P7 | Bonobo Pan paniscus | 2017 | March | Lungs with miliary necroses, inflammatory cells, and bacterial foci; multifocal colliquation necrosis in liver and spleen | Liver, lungs, kidney | Stuttgart |

| P8 | Bonobo Pan paniscus | 2017 | March | Feces | Feces | Stuttgart |

| P9 | Brown spider monkey Ateles hybridus | 2019 | December | Spleen, liver, mesenteric lymph nodes with highly multifocal foci of necrosis with bacterial foci, lymphoplasmacellular necrotizing enteritis | Liver, spleen, intestine | Munich |

| P10 | Brown spider monkey Ateles hybridus | 2020 | February | Multifocal necrotizing hepatitis and splenitis, necrotizing myelitis with evidence of bacterial foci, diffuse catarrhal enteritis | Spleen | Neuwied |

| P11 | Cotton-headed tamarin Saguinus oedipus | 2021 | April | High-grade multifocal necrotizing inflammation of liver | Liver | IVP Zurich |

| P12 | De Brazza’s monkey Cercopithecus neglectus | 2021 | March | Necrotizing enteritis, splenitis, hepatitis, and pneumonia | Liver, lungs, spleen, kidney, intestine, heart | Donnersberg |

| P13 | Emperor tamarin Saguinus imperator | 2015 | November | Multifocal purulent-necrotizing hepatitis, multifocal necrotizing splenitis; follicular hyperplasia and marked extramedullary hematopoiesis of the spleen | Liver, spleen, intestine | Neuwied |

| P14 | Emperor tamarin Saguinus imperator | 2019 | December | Multiple granulomas in the liver parenchyma and spleen; generalized high-grade lymphatic hyperplasia | Liver, spleen, kidney, intestine | Private owner |

| P15 | Geoffroy’s spider monkeys Ateles geoffroyi | 2022 | February | High-grade multifocal necrotizing inflammation of liver, liver capsular fibrosis, renal cysts, moderate non-suppurative nephritis | Liver | Karlsruhe |

| P16 | Goeldi‘s marmoset Callimico goeldii | 2022 | December | Multifocal pyogranulomatous hepatitis, diphtheroid-necrotizing enterocolitis with lymph follicle proliferation, moderate splenomegaly | Liver, spleen | Stuttgart |

| P17 | Patas monkey Erythrocebus patas | 2019 | November | Hyperplasia of spleen with colliquation necrosis, hepatitis with histiocytic infiltration, pyogranulomatous enteritis and necrotizing mesenteric lymphadenitis | Liver, spleen | Hamm |

| P18 | Roloway monkey Cercopithecus roloway | 2023 | January | Necrotic foci in liver and spleen, granulomatous enteritis, splenomegaly, hyperplasia of mesenteric lymph nodes | Liver, spleen, lungs, kidney, intestine | Duisburg |

| Case No. | Species | Order | Year | Month | Gross Pathological Findings | Source of Y. pseudotuberculosis | Zoo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | Black grouse Lyrurus tetrix | Galliformes | 2013 | December | Liver and spleen highly enlarged with heterophilic infiltrates, lungs with heterophilic infiltrates and bacteria | Feces, intestine | Walsrode |

| B2 | Black-naped Oriole Oriolus chinensis | Passeriformes | 2014 | January | n.a. 1 | Swab sample from organs | Walsrode |

| B3 | Black-necked aracari Pteroglossus aracari | Piciformes | 2013 | February | Granulomatous hepatitis and pneumonia with miliary necroses and bacterial foci | Liver, lungs, heart | Walsrode |

| B4 | Black-necked aracari Pteroglossus aracari | Piciformes | 2021 | February | Liver and spleen with highly multifocal necroses with bacterial foci, kidney and lungs with bacterial foci and inflammatory infiltrates | Intestine, heart, visceral cavity, blood | Walsrode |

| B5 | Blue-faced honeyeater Entomyzon cyanotis | Passeriformes | 2022 | January | Catarrhal-hemorrhagic enteritis | Liver, lungs, intestine, blood | Heidelberg |

| B6 | Capuchinbird Perissocephalus tricolor | Passeriformes | 2014 | January | Liver enlarged, multiple granulomas, fibrinous inflammation and hemosidero-phagocytosis in liver, lungs, spleen | Liver, lungs | Walsrode |

| B7 | Channel-billed toucan Ramphastos vitellinus | Piciformes | 2021 | May | Liver, lungs, adrenal gland, kidney with highly multifocal necroses with bacterial foci and arteriosclerosis | Liver, lungs, blood | Walsrode |

| B8 | Channel-billed toucan Ramphastos vitellinus | Piciformes | 2017 | December | Spleen, liver, kidney with highly multifocal heterophilic granulomas, inflammatory infiltrates, and bacterial foci | Liver, lungs, intestine, heart, kidney | Walsrode |

| B9 | Chestnut-eared aracari Pteroglossus castanotis | Piciformes | 2016 | April | Fibrinous hepatitis, splenitis, enteritis, nephritis, and pneumonia with bacterial foci | Liver, lungs, intestine, heart | Walsrode |

| B10 | Chestnut-eared aracari Pteroglossus castanotis | Piciformes | 2021 | May | Liver, spleen, lungs with high-grade multifocal necroses, bacterial foci, and moderate inflammatory infiltrates and granulomas | Liver, lungs | Walsrode |

| B11 | Common redshank Tringa totanus | Scolopacidae | 2021 | January | Liver, lungs, kidneys with bacterial emboli in the vessels partly with necrosis, hepatomegaly, cachexia | Liver, lungs, heart | Stuttgart |

| B12 | Eastern rosella Platycercus eximius | Psittaciformes | 2023 | November | Liver with multifocal necroses, bacterial foci, and inflammatory infiltrates; lungs and spleen with multifocal pyogranulomas and bacterial foci | Liver, lungs, intestine, heart | Stuttgart |

| B13 | Golden-headed quetzal Pharomachrus auriceps | Trogoniformes | 2017 | December | Liver, lungs, adrenal gland, kidney with severe multifocal necroses; bacterial foci and inflammatory infiltrates; hepatomegaly, splenomegaly | Liver, lungs, heart, visceral cavity | Walsrode |

| B14 | Golden-headed quetzal Pharomachrus auriceps | Trogoniformes | 2022 | November | Lungs with edema and bacterial foci, liver with mild necrosis, bacterial foci, and inflammatory infiltrates | Liver, lungs, heart, kidney | Walsrode |

| B15 | Golden-headed quetzal Pharomachrus auriceps | Trogoniformes | 2022 | November | Liver with severe multifocal necroses with bacterial foci, lungs and kidneys with bacterial foci | Liver, lungs, intestine, heart | Walsrode |

| B16 | Green Aracari Pteroglossus viridis | Piciformes | 2008 | n.a. 1 | Liver and spleen with miliary necroses, moderate catarrhal enteritis, cachexia | Liver, intestine, spleen | Berlin |

| B17 | Green Aracari Pteroglossus viridis | Piciformes | 2008 | n.a. 1 | Severe pneumonia, moderate splenomegaly, severe hemorrhagic enteritis, cachexia | Lungs, spleen | Berlin |

| B18 | Green Aracari Pteroglossus viridis | Piciformes | 2014 | February | n.a. 1 | Liver, lungs | Walsrode |

| B19 | Green Aracari Pteroglossus viridis | Piciformes | 2021 | February | n.a. 1 | Visceral cavity | Walsrode |

| B20 | King bird-of-paradise Cicinnurus regius | Passeriformes | 2023 | February | Liver, spleen, lungs, ovary, serosa with high-grade and small intestine and kidney with low-grade multifocal necroses with bacterial foci | Liver, lungs, ovaries, blood | Walsrode |

| B21 | Lesser flamingo Phoeniconaias minor | Phoenicopteriformes | 2024 | January | Liver, serosa, ovary, with miliary necroses; ascites, cachexia | Liver, lungs, heart, kidney, ovaries | Kronberg |

| B22 | Madagascar turtle dove Streptopelia picturata | Columbiformes | 2008 | n.a. 1 | Multiple granulomas in the liver, hemorrhagic enteritis | Liver | Berlin |

| B23 | Magpie Shrike Lanius melanoleucus | Passeriformes | 2013 | January | Liver and spleen severely enlarged with multifocal necroses and bacterial foci | Liver | Walsrode |

| B24 | Metallic pigeon Columba vitiensis | Columbiformes | 2014 | January | Inflammation and multiple granulomas in the liver, fibrinous splenitis and pneumonia, hemorrhagic enteritis | Intestine | Walsrode |

| B25 | Pale-winged trumpeter Psophia leucoptera | Gruiformes | 2015 | November | Liver, kidney, spleen with severe multifocal fibrinous inflammation with bacterial foci, pneumoconiosis | Liver, lungs, heart, visceral cavity | Walsrode |

| B26 | Pompadour cotinga Xipholena punice | Passeriformes | 2008 | n.a. 1 | Severe granulomatous hepatitis, splenitis, and nephritis | Liver, spleen, kidney | Berlin |

| B27 | Raggiana Bird-of-paradise Paradisaea raggiana | Passeriformes | 2021 | February | Liver, lungs, spleen with severe multifocal necroses and inflammation with bacterial foci, kidney with bacterial foci | Liver, lungs, brain, blood, feces | Walsrode |

| B28 | Raggiana Bird-of-paradise Paradisaea raggiana | Passeriformes | 2021 | September | n.a. 1 | Feces, throat | Walsrode |

| B29 | Red-and-yellow barbet Trachyphonus erythrocephalus | Piciformes | 2014 | March | n.a. 1 | Liver, lungs | Walsrode |

| B30 | Red-rumped parrot Psephotus haematonotus | Psittaciformes | 2023 | January | Miliary necrotizing hepatitis with bacterial foci, hemorrhagic-catarrhal enteritis, cachexia | Liver, lungs, intestine, heart | Stuttgart |

| B31 | Red-rumped parrot Psephotus haematonotus | Psittaciformes | 2023 | November | Miliary granulomatous necrotizing hepatitis, splenitis and encephalitis, diffuse satellitosis, tubulonecrosis, glomerulo-proliferation and single granulomas in kidney | Liver, heart | Stuttgart |

| B32 | Spotted dove Spilopelia chinensis | Columbiformes | 2022 | November | Multifocal pyogranulomatous pneumonia with bacterial foci | Liver, lungs, heart | Stuttgart |

| B33 | Toco toucan Ramphastos toco | Piciformes | 2020 | December | Moderate hepatomegaly, severe splenomegaly, severe miliary necroses in liver and spleen, pneumonia | Liver, lungs, spleen, kidney, heart | Wuppertal |

| B34 | Toco toucan Ramphastos toco | Piciformes | 2013 | January | Liver and spleen enlarged, pericardium clouded with fluid accumulation, lungs highly reddened with fluid accumulation | Liver, lungs, intestine, heart, blood | Walsrode |

| B35 | Toco toucan Ramphastos toco | Piciformes | 2018 | January | Liver and spleen with highly multifocal necroses with bacterial foci, in intestine and lungs, bacterial foci, and inflammatory infiltrates | Liver | Walsrode |

| B36 | Toco toucan Ramphastos toco | Piciformes | 2021 | February | n.a. 1 | Liver, lungs, heart, visceral cavity | Walsrode |

| B37 | Toco toucan Ramphastos toco | Piciformes | 2023 | February | Liver and spleen with high-grade multifocal necroses with bacterial foci, bacterial foci in the lungs | Liver, lungs, visceral cavity, blood | Walsrode |

| B38 | Toco toucan Ramphastos toco | Piciformes | 2023 | February | Liver and spleen with high-grade multifocal necroses with bacterial foci and inflammatory infiltrates, bacterial foci in the lungs | Liver, lungs, blood | Walsrode |

| B39 | White-crested turaco Tauraco leucolophus | Musophagiformes | 2013 | February | Granulomas, inflammatory infiltrates, and masses of bacteria in liver, spleen, heart valve, small intestine, and kidney | Liver, lungs, heart | Walsrode |

| B40 | White-throated toucan Ramphastos tucanus | Piciformes | 2013 | March | n.a. 1 | Liver, intestine, heart | Walsrode |

| B41 | White-throated toucan Ramphastos tucanus | Piciformes | 2012 | March | Liver and spleen severely enlarged with multifocal necroses, villous fusion and atrophy of the intestine | Liver, intestine | Walsrode |

| Subst. Abbrev. | CTX | S | TE | IMI | AK | CHL | CN | NOR | MER | AMC | NAL | W | SXT | AMP | CIP | CAZ | FEP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | 267 | 268 | 247 | 269 | 270 | 269 | 266 | 270 | 266 | 262 | 269 | 269 | 269 | 264 | 269 | 265 | 267 |

| I | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| R | 3 | 1 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Riede, L.L.; Knauf-Witzens, T.; Westerhüs, U.; Bonke, R.; Schlez, K.; Büttner, K.; Rau, J.; Fischer, D.; Grund, L.; Roller, M.; et al. Occurrence and Monitoring of the Zoonotic Pathogen Yersinia pseudotuberculosis in Various Zoo Animal Species. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13030516

Riede LL, Knauf-Witzens T, Westerhüs U, Bonke R, Schlez K, Büttner K, Rau J, Fischer D, Grund L, Roller M, et al. Occurrence and Monitoring of the Zoonotic Pathogen Yersinia pseudotuberculosis in Various Zoo Animal Species. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(3):516. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13030516

Chicago/Turabian StyleRiede, Lara Luisa, Tobias Knauf-Witzens, Uta Westerhüs, Rebecca Bonke, Karen Schlez, Kathrin Büttner, Jörg Rau, Dominik Fischer, Lisa Grund, Marco Roller, and et al. 2025. "Occurrence and Monitoring of the Zoonotic Pathogen Yersinia pseudotuberculosis in Various Zoo Animal Species" Microorganisms 13, no. 3: 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13030516

APA StyleRiede, L. L., Knauf-Witzens, T., Westerhüs, U., Bonke, R., Schlez, K., Büttner, K., Rau, J., Fischer, D., Grund, L., Roller, M., Frei, A., Hertwig, S., Hammerl, J. A., Jäckel, C., Osmann, C., Peters, M., Sting, R., & Eisenberg, T. (2025). Occurrence and Monitoring of the Zoonotic Pathogen Yersinia pseudotuberculosis in Various Zoo Animal Species. Microorganisms, 13(3), 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13030516