Biosynthetic Pathways and Functions of Indole-3-Acetic Acid in Microorganisms

Abstract

1. Introduction

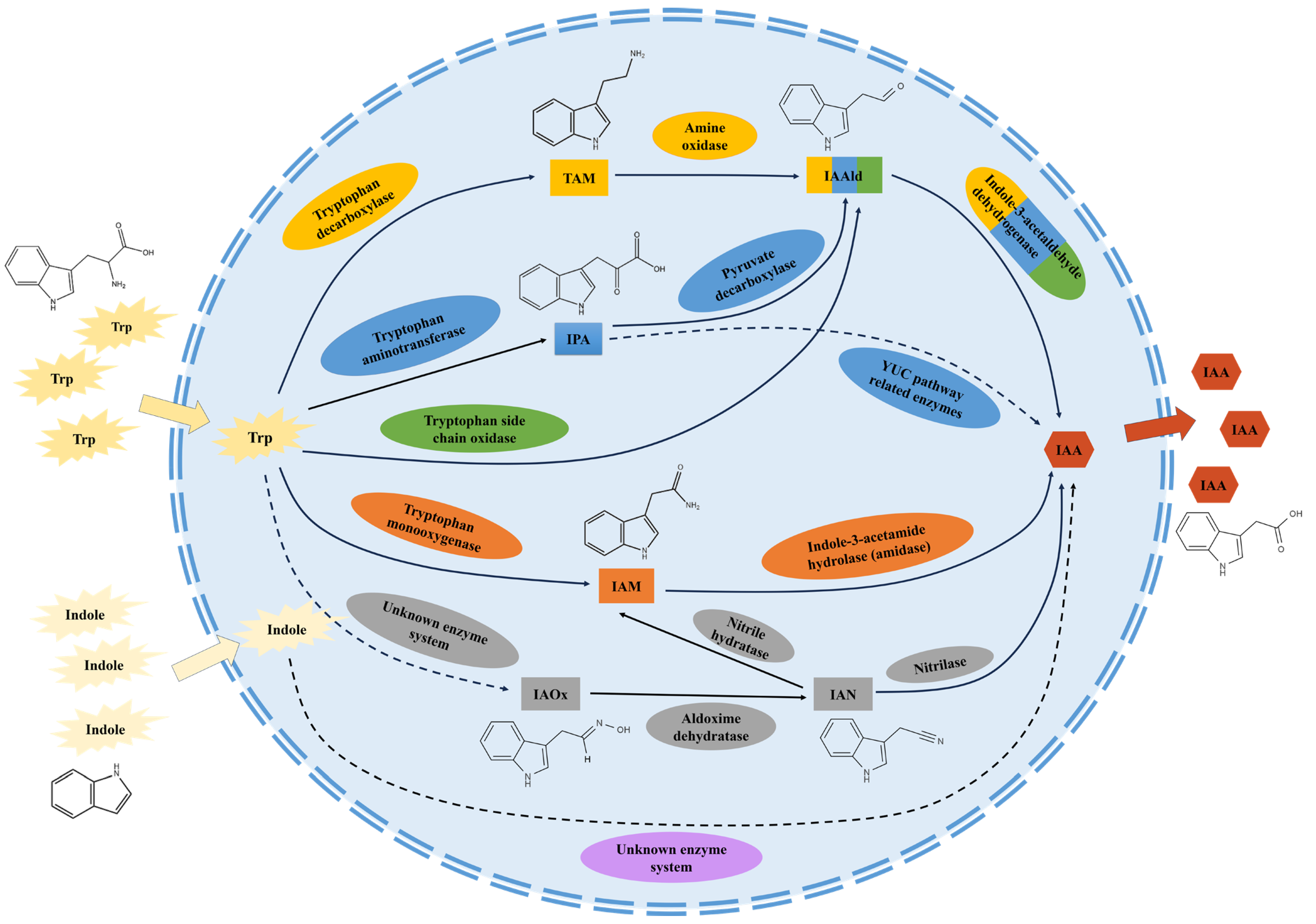

2. Biosynthetic Pathways of IAA in Microorganisms

2.1. The IAM Pathway

2.2. The IPA Pathway

2.3. The TAM Pathway

2.4. The IAN Pathway

2.5. The TSO Pathway

2.6. Non-Tryptophan-Dependent Pathway

3. Interactive Effect of Multiple IAA Biosynthetic Pathways in a Microorganism

4. The Functions of IAA in Microorganisms

5. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grossmann, K. Auxin herbicides: Current status of mechanism and mode of action. Pest Manag. Sci. 2010, 66, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McSteen, P. Auxin and monocot development. Csh. Perspect. Biol. 2010, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianco, C.; Defez, R. Medicago truncatula improves salt tolerance when nodulated by an indole-3-acetic acid-overproducing Sinorhizobium meliloti strain. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 3097–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limtong, S.; Koowadjanakul, N. Yeasts from phylloplane and their capability to produce indole-3-acetic acid. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 28, 3323–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruanpanun, P.; Tangchitsomkid, N.; Hyde, K.D.; Lumyong, S. Actinomycetes and fungi isolated from plant-parasitic nematode infested soils: Screening of the effective biocontrol potential, indole-3-acetic acid and siderophore production. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 26, 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaepen, S.; Vanderleyden, J.; Remans, R. Indole-3-acetic acid in microbial and microorganism-plant signaling. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2007, 31, 425–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. Auxin biosynthesis and its role in plant development. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaepen, S.; Vanderleyden, J. Auxin and plant-microbe interactions. Csh. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, a001438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patten, C.L.; Blakney, A.J.C.; Coulson, T.J.D. Activity, distribution and function of indole-3-acetic acid biosynthetic pathways in bacteria. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 39, 395–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teale, W.D.; Paponov, I.A.; Palme, K. Auxin in action: Signalling, transport and the control of plant growth and development. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 7, 847–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Puyvelde, S.; Cloots, L.; Engelen, K.; Das, F.; Marchal, K.; Vanderleyden, J.; Spaepen, S. Transcriptome analysis of the rhizosphere racterium Azospirillum brasilense reveals an extensive auxin response. Microb. Ecol. 2011, 61, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, A.W.; Bonnie, B. Auxin: Regulation, action, and interaction. Ann. Bot. 2005, 95, 707–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barriuso, J.; Hogan, D.A.; Keshavarz, T.; Martinez, M.J. Role of quorum sensing and chemical communication in fungal biotechnology and pathogenesis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 42, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padder, S.A.; Prasad, R.; Shah, A.H. Quorum sensing: A less known mode of communication among fungi. Microbiol. Res. 2018, 210, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahemad, M.; Kibret, M. Mechanisms and applications of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria: Current perspective. J. King Saud Uni. Sci. 2014, 26, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Comai, L.; Kosuge, T. Cloning characterization of iaaM, a virulence determinant of Pseudomonas savastanoi. J. Bacteriol. 1982, 149, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, T.T.; Kosuge, T. Role of aminotransferase and indole-3-pyruvic acid in the synthesis of indole-3-acetic acid in Pseudomonas savastanoi. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 1970, 16, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mashiguchi, K.; Hisano, H.; Takeda-Kamiya, N.; Takebayashi, Y.; Ariizumi, T.; Gao, Y.B.; Ezura, H.; Sato, K.; Zhao, Y.; Hayashi, K.; et al. Agrobacterium tumefaciens Enhances Biosynthesis of Two Distinct Auxins in the Formation of Crown Galls. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019, 60, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numponsak, T.; Kumla, J.; Suwannarach, N.; Matsui, K.; Lumyong, S. Biosynthetic pathway and optimal conditions for the production of indole-3-acetic acid by an endophytic fungus, Colletotrichum fructicola CMU-A109. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsavkelova, E.A.; Klimova, S.Y.; Cherdyntseva, T.A.; Netrusov, A.I. Microbial producers of plant growth stimulators and their practical use: A review. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2006, 42, 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Maor, R.; Haskin, S.; Levi-Kedmi, H.; Sharon, A. In planta production of indole-3-acetic acid by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides f. sp. aeschynomene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 1852–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Xu, X.D. Indole-3-acetic acid production by endophytic Streptomyces sp. En-1 isolated from medicinal plants. Curr. Microbiol. 2013, 67, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costacurta, A.; Keijers, V.; Vanderleyden, J. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of an Azospirillum brasilense indole-3-pyruvate decarboxylase gene. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1994, 243, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spaepen, S.; Dobbelaere, S.; Croonenborghs, A.; Vanderleyden, J. Effects of Azospirillum brasilense indole-3-acetic acid production on inoculated wheat plants. Plant Soil 2008, 312, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theunis, M.; Kobayashi, H.; Broughton, W.J.; Prinsen, E. Flavonoids, NodD1, NodD2, and Nod-Box NB15 modulate expression of the y4wEFG locus that is required for indole-3-acetic acid synthesis in Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2004, 17, 1153–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apine, O.A.; Jadhav, J.P. Optimization of medium for indole-3-acetic acid production using Pantoea agglomerans strain PVM. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 110, 1235–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinsen, E. Azospirillum brasilense indole-3-acetic acid biosynthesis: Evidence for a non-tryptophan dependent pathway. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 1993, 6, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueredo, E.F.; Cruz, T.A.d.; Almeida, J.R.d.; Batista, B.D.; Marcon, J.; Andrade, P.A.M.d.; Hayashibara, C.A.d.A.; Rosa, M.S.; Azevedo, J.L.; Quecine, M.C. The key role of indole-3-acetic acid biosynthesis by Bacillus thuringiensis RZ2MS9 in promoting maize growth revealed by the ipdC gene knockout mediated by the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 266, 127218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.X.; Li, P.S.; Wang, Y.Y.; Wang, J.J.; Liu, X.L.; Wang, X.Y.; Hu, X.M. Characterization and synthesis of indole-3-acetic acid in plant growth promoting Enterobacter sp. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 31601–31607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basse, C.W.; Lottspeich, F.; Steglich, W.; Kahmann, R. Two potential indole-3-acetaldehyde dehydrogenases in the phytopathogenic fungus Ustilago maydis. Eur. J. Biochem. 2010, 242, 648–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, W. Biosynthesis and secretion of indole-3-acetic acid and its morphological effects on Tricholoma vaccinum-spruce ectomycorrhiza. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 7003–7011. [Google Scholar]

- Zuther, K.; Mayser, P.; Hettwer, U.; Wu, W.Y.; Spiteller, P.; Kindler, B.L.J.; Karlovsky, P.; Basse, C.W.; Schirawski, J. The tryptophan aminotransferase tam1 catalyses the single biosynthetic step for tryptophan-dependent pigment synthesis in Ustilago maydis. Mol. Microbiol. 2008, 68, 152–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, W.L.; Okmen, B.; Depotter, J.R.L.; Ebert, M.K.; Redkar, A.; Villamil, J.M.; Doehlemann, G. Molecular Interactions between smut fungi and their host plants. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2019, 57, 411–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, G.B.; Huang, C.W.; Bi, X.P.; Wang, Y.X.; Yin, K.; Zhu, L.Y.; Jiang, Z.D.; Chen, B.S.; Deng, Y.Z. Aminotransferase SsAro8 regulates tryptophan metabolism essential for filamentous growth of sugarcane smut fungus Sporisorium scitamineum. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 18, e0057022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, E.P.; Li, L.Y.; Deng, Y.Z.; Sun, S.Q.; Jia, H.; Wu, R.R.; Zhang, L.H.; Jiang, Z.D.; Chang, C.Q. MAP kinase Hog1 mediates a cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase to promote the Sporisorium scitamineum cell survival under oxidative stress. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 3306–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, L.H.; Ma, Y.M.; Chen, C.Y.; Shen, L.Z.; Sun, W.D.; Cui, G.B.; Naqvi, N.I.; Deng, Y.Z. Identification and characterization of auxin/IAA biosynthesis pathway in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumla, J.; Suwannarach, N.; Matsui, K.; Lumyong, S. Biosynthetic pathway of indole-3-acetic acid in ectomycorrhizal fungi collected from northern Thailand. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayssieres, A.; Pencik, A.; Felten, J.; Kohler, A.; Ljung, K.; Martin, F.; Legue, V. Development of the poplar-Laccaria bicolor ectomycorrhiza modifies root auxin metabolism, signaling, and response. Plant Physiol. 2015, 169, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stowe, P. On the Ability of Taphrina deformans to produce indoleacetic acid from tryptophan by way of tryptamine. Plant Physiol. 1966, 41, 234–237. [Google Scholar]

- Bunsangiam, S.; Sakpuntoon, V.; Srisuk, N.; Ohashi, T.; Fujiyama, K.; Limtong, S. Biosynthetic pathway of indole-3-acetic acid in basidiomycetous yeast Rhodosporidiobolus fluvialis. Mycobiology 2019, 47, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.G.; Lovett, B.; Fang, W.G.; St Leger, R.J. Metarhizium robertsii produces indole-3-acetic acid, which promotes root growth in Arabidopsis and enhances virulence to insects. Microbiology 2017, 163, 980–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bak, S.; Tax, F.E.; Feldmann, K.A.; Galbraith, D.W.; Feyereisen, R. CYP83B1, a cytochrome P450 at the metabolic branch point in auxin and indole glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2001, 13, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartling, D.; Seedorf, M.; Mithofer, A.; Weiler, E.W. Cloning and expression of an Arabidopsis nitrilase which can convert indole-3-acetonitrile to the plant hormone, indole-3-acetic acid. Eur. J. Biochem. 1992, 205, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Christensen, S.K.; Fankhauser, C.; Cashman, J.R.; Cohen, J.D.; Weigel, D.; Chory, J. A role for flavin monooxygenase-like enzymes in auxin biosynthesis. Science 2001, 291, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Wang, Z.; Ding, K.; Chen, Y.; Asano, Y. Recent progress on discovery and research of aldoxime dehydratases. Green Synth. Catal. 2021, 2, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radisch, R.; Patek, M.; Kristkova, B.; Winkler, M.; Kren, V.; Martinkova, L. Metabolism of aldoximes and nitriles in plant-associated bacteria and its potential in plant-bacteria interactions. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedras, M.S.C.; Minic, Z.; Thongbam, P.D.; Bhaskar, V.; Montaut, S. Indolyl-3-acetaldoxime dehydratase from the phytopathogenic fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum Purification, characterization, and substrate specificity. Phytochemistry 2010, 71, 1952–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radisch, R.; Chmatal, M.; Rucka, L.; Novotny, P.; Petraskova, L.; Halada, P.; Kotik, M.; Patek, M.; Martinkova, L. Overproduction and characterization of the first enzyme of a new aldoxime dehydratase family in Bradyrhizobium sp. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 115, 746–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.L.; Yang, W.L.; Fang, W.W.; Zhao, Y.X.; Guo, L.; Dai, Y.J. The plant growth-promoting Rhizobacterium Variovorax boronicumulans CGMCC 4969 regulates the level of indole-3-acetic acid synthesized from indole-3-acetonitrile. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e00298-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.H.; Li, Y.C.; Li, Z.F.; Xu, Z.H.; Xun, W.B.; Zhang, N.; Feng, H.C.; Miao, Y.Z.; Shen, Q.R.; Zhang, R.F. Participating mechanism of a major contributing gene ysnE for auxin biosynthesis in Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SQR9. J. Basic Microbiol. 2021, 61, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leontovycova, H.; Trda, L.; Dobrev, P.I.; Sasek, V.; Gay, E.; Balesdent, M.H.; Burketova, L. Auxin biosynthesis in the phytopathogenic fungus Leptosphaeria maculans is associated with enhanced transcription of indole-3-pyruvate decarboxylase LmIPDC2 and tryptophan aminotransferase LmTAM1. Res. Microbiol. 2020, 171, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.S.; Guo, R.; Yu, F.; Chen, X.; Zhao, H.Y.; Li, H.X.; Wu, J. Indole-3-acetic acid biosynthesis pathways in the plant-beneficial bacterium Arthrobacter pascens ZZ21. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberhansli, T.; Defago, G.; Haas, D. Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) synthesis in the biocontrol strain CHA0 of Pseudomonas fluorescens: Role of tryptophan side chain oxidase. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1991, 137, 2273–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, R.P.; Hunter, A.; Kashpur, O.; Normanly, J. Aberrant Synthesis of indole-3-acetic acid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae triggers morphogenic transition, a virulence trait of pathogenic fungi. Genetics 2010, 185, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, L.; Hofmann, U.; Ludwig-Muller, J. Indole-3-acetic acid Is synthesized by the endophyte Cyanodermella asteris via a tryptophan-dependent and -independent way and mediates the interaction with a non-host plant. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duca, D.; Rose, D.R.; Glick, B.R. Characterization of a nitrilase and a nitrile hydratase from Pseudomonas sp. strain UW4 that converts indole-3-acetonitrile to indole-3-acetic acid. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 4640–4649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, J.; Wei, J.; Cheng, Z.; Heikkila, J.J.; Glick, B.R.; John, V. The complete genome sequence of the plant growth-promoting bacterium Pseudomonas sp. UW4. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58640. [Google Scholar]

- Pantoja-Guerra, M.; Burkett-Cadena, M.; Cadena, J.; Dunlap, C.A.; Ramirez, C.A. Lysinibacillus spp.: An IAA-producing endospore forming-bacteria that promotes plant growth. Anton. Leeuw. 2023, 116, 615–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.L.; Zhang, M.L.; Kong, Z.R.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Ding, W.; Lai, H.X.; Guo, Q. Genomic analysis reveals potential mechanisms underlying promotion of tomato plant growth and antagonism of soilborne pathogens by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Ba13. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, G.B.; Sanjeevkumar, S.; Kirankumar, B.; Santoshkumar, M.; Karegoudar, T.B. Indole-3-acetic acid biosynthesis in Fusarium delphinoides strain GPK, a causal agent of wilt in chickpea. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2013, 169, 1292–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tullio, L.D.; Nakatani, A.S.; Gomes, D.F.; Ollero, F.J.; Megias, M.; Hungria, M. Revealing the roles of y4wF and tidC genes in Rhizobium tropici CIAT 899: Biosynthesis of indolic compounds and impact on symbiotic properties. Arch. Microbiol. 2019, 201, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbert, M.; Voll, L.M.; Ding, Y.; Hofmann, J.; Sharma, M.; Zuccaro, A. Indole derivative production by the root endophyte Piriformospora indica is not required for growth promotion but for biotrophic colonization of barley roots. New Phytol. 2012, 196, 520–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, M.; Riov, J.; Sharon, A. Indole-3-acetic acid biosynthesis in Colletotrichum gloeosporioides f. sp. aeschynomene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 5030–5032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, D.H.; Wang, S.S.; Cui, M.M.; Liu, J.H.; Chen, A.Q.; Xu, G.H. Phytohormones regulate the development of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.F.; Fang, W.T.; Shin, L.Y.; Wei, J.Y.; Fu, S.F.; Chou, J.Y. Indole-3-acetic acid-producing yeasts in the phyllosphere of the carnivorous plant Drosera indica L. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, K.; Rocheleau, H.; Qi, P.F.; Zheng, Y.L.; Zhao, H.Y.; Ouellet, T. Indole-3-acetic acid in Fusarium graminearum: Identification of biosynthetic pathways and characterization of physiological effects. Fungal Biol. 2016, 120, 1135–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karygianni, L.; Ren, Z.; Koo, H.; Thurnheer, T. Biofilm matrixome: Extracellular components in structured microbial communities. Trends Microbiol. 2020, 8, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, C.; Imperlini, E.; Defez, R. Legumes like more IAA. Plant Signal. Behav. 2009, 4, 763–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyagi, M.; Wilson, R.; Saigusa, D.; Umeda, K.; Saijo, R.; Hager, C.L.; Li, Y.J.; McCormick, T.; Ghannoum, M.A. Indole-3-acetic acid synthesized through the indole-3-pyruvate pathway promotes Candida tropicalis biofilm formation. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.W.; Wang, Y.D.; Yang, P.C.; Wang, C.S.; Kang, L. Tryptamine accumulation caused by deletion of MrMao-1 in Metarhizium genome significantly enhances insecticidal virulence. PLoS Genet. 2020, 16, e1008675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singkum, P.; Muangkaew, W.; Suwanmanee, S.; Pumeesat, P.; Wongsuk, T.; Luplertlop, N. Suppression of the pathogenicity of Candida albicans by the quorum-sensing molecules farnesol and tryptophol. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 65, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.; Go, G.W.; Mylonakis, E.; Kim, Y. The bacterial signalling molecule indole attenuates the virulence of the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 113, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djami-Tchatchou, A.T.; Harrison, G.A.; Harper, C.P.; Wang, R.H.; Prigge, M.J.; Estelle, M.; Kunkel, B.N. Dual role of auxin in regulating plant defense and bacterial virulence gene expression during Pseudomonas syringae PtoDC3000 pathogenesis. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2020, 33, 1059–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert-Seilaniantz, A.; Grant, M.; Jones, J.D.G. Hormone crosstalk in plant disease and defense: More than just jasmonate-salicylate antagonism. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2011, 49, 317–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhaus, K.; Grsic-Rausch, S.; Sauerteig, S.; Ludwig-Müller, J. Arabidopsis plants transformed with nitrilase 1 or 2 in antisense direction are delayed in clubroot development. J. Plant Physiol. 2000, 156, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutka, A.M.; Fawley, S.; Tsao, T.; Kunkel, B.N. Auxin promotes susceptibility to Pseudomonas syringae via a mechanism independent of suppression of salicylic acid-mediated defenses. Plant J. 2013, 74, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.F.; Wei, J.Y.; Chen, H.W.; Liu, Y.Y.; Lu, H.Y.; Chou, J.Y. Indole-3-acetic acid: A widespread physiological code in interactions of fungi with other organisms. Plant Signal. Behav. 2015, 10, e1048052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, G.B.; Sajjan, S.S.; Karegoudar, T.B. Pathogenicity of indole-3-acetic acid producing fungus Fusarium delphinoides strain GPK towards chickpea and pigeon pea. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2011, 131, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doehlemann, G.; Wahl, R.; Horst, R.J.; Voll, L.M.; Usadel, B.; Poree, F.; Stitt, M.; Pons-Kuhnemann, J.; Sonnewald, U.; Kahmann, R.; et al. Reprogramming a maize plant: Transcriptional and metabolic changes induced by the fungal biotroph Ustilago maydis. Plant J. 2008, 56, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemetsberger, C.; Herrberger, C.; Zechmann, B.; Hillmer, M.; Doehlemann, G. The Ustilago maydis effector Pep1 suppresses plant immunity by inhibition of host peroxidase activity. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.X.; Feng, Q.; Cao, X.L.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, H.; Chandran, V.; Fan, J.; Zhao, J.Q.; Pu, M.; Li, Y.; et al. Osa-miR167d facilitates infection of Magnaporthe oryzae in rice. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2020, 62, 702–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Liu, H.B.; Li, Y.; Yu, H.H.; Li, X.H.; Xiao, J.H.; Wang, S.P. Manipulating broad-spectrum disease resistance by suppressing pathogen-induced auxin accumulation in rice. Plant Physiol. 2011, 155, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, X.P.; Long, J.H.; Zhao, K.; Peng, A.H.; Chen, M.; Long, Q.; He, Y.R.; Chen, S.C. Overexpressing GH3.1 and GH3.1L reduces susceptibility to Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri by repressing auxin signaling in citrus (Citrus sinensis Osbeck). PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, L.L.; Zheng, L.Y.; Sheng, C.; Zhao, H.W.; Jin, H.L.; Niu, D.D. Rice siR109944 suppresses plant immunity to sheath blight and impacts multiple agronomic traits by affecting auxin homeostasis. Plant J. 2020, 102, 948–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Q.Q.; Li, G.Y.; Jin, L.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wei, C.H.; Xu, Z.H.; Yang, Z.R.; Wang, H.Y.; Li, Y. Auxin response factors (ARFs) differentially regulate rice antiviral immune response against rice dwarf virus. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1009118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taghavi, S.; Garafola, C.; Monchy, S.; Newman, L.; Hoffman, A.; Weyens, N.; Barac, T.; Vangronsveld, J.; van der Lelie, D. Genome survey and characterization of endophytic bacteria exhibiting a beneficial effect on growth and development of poplar trees. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 748–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facella, P.; Daddiego, L.; Giuliano, G.; Perrotta, G. Gibberellin and auxin influence the diurnal transcription pattern of photoreceptor genes via CRY1a in tomato. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30121. [Google Scholar]

- Lambrecht, M.; Okon, Y.; Vande Broek, A.; Vanderleyden, J. Indole-3-acetic acid: A reciprocal signalling molecule in bacteria-plant interactions. Trends Microbiol. 2000, 8, 298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, D.; Laha, S. Production of phytohormone auxin (IAA) from soil born Rhizobium sp., isolated from different leguminous plant. Int. J. Appl. Environ. Sci. 2013, 8, 521–528. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.L.; Yu, Z.P.; Zhang, M.Y.; Li, X.X.; Wang, M.J.; Li, L.X.; Li, X.G.; Ding, Z.J.; Tian, H.Y. Serratia marcescens PLR enhances lateral root formation through supplying PLR-derived auxin and enhancing auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 3711–3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.N.; Zhang, J.C.; Wang, X.F.; An, J.P.; You, C.X.; Zhou, B.; Hao, Y.J. The Growth-promoting mechanism of Brevibacillus laterosporus AMCC100017 on apple rootstock Malus robusta. Hortic. Plant J. 2022, 8, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, M.; Qureshi, M.A.; Zahir, Z.A.; Hussain, M.B.; Sessitsch, A.; Mitter, B. L-Tryptophan-dependent biosynthesis of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) improves plant growth and colonization of maize by Burkholderia phytofirmans PsJN. Ann. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 1381–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Dong, Z.; Che, Y.; Lu, S.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X. AM fungi Glomous mosseae promote tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) growth by regulating IAA metabolism. J. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 27, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, M.; Srivastava, S. An ipdC gene knock-out of Azospirillum brasilense strain SM and its implications on indole-3-acetic acid biosynthesis and plant growth promotion. Anton. Leeuw. 2008, 93, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, J.; Samavati, R.; Jalili, B.; Bagheri, H.; Hamzei, J. Halotolerant endophytic bacteria from desert-adapted halophyte plants alleviate salinity stress in germinating seeds of the common wheat Triticum aestivum L. Cereal Res. Commun. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.M.; Ul Hoque, M.I.; Woo, J.I.; Lee, I.J. Mitigation of salinity stress on soybean seedlings using indole acetic acid-producing Acinetobacter pittii YNA40. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, S.; Iqbal, A.; Ahmed, F.; Ahmad, M. Phytobeneficial and salt stress mitigating efficacy of IAA producing salt tolerant strains in Gossypium hirsutum. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 5317–5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arif, S.; Munis, M.F.H.; Liaquat, F.; Gulzar, S.; Haroon, U.; Zhao, L.A.; Zhang, Y.D. Trichoderma viride establishes biodefense against clubroot (Plasmodiophora brassicae) and fosters plant growth via colonizing root hairs in pak choi (Brassica campestris spp. chinesnsis). Biol. Control 2023, 183, 105265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.J.; Cao, S.L.; Liao, S.J.; Wassie, M.; Sun, X.Y.; Chen, L.; Xie, Y. Fusarium equiseti-inoculation altered rhizosphere soil microbial community, potentially driving perennial ryegrass growth and salt tolerance. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 871, 162153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, A.; Ghosh, P.K.; Pramanik, K.; Mitra, S.; Soren, T.; Pandey, S.; Mondal, M.H.; Maiti, T.K. A halotolerant Enterobacter sp. displaying ACC deaminase activity promotes rice seedling growth under salt stress. Res. Microbiol. 2018, 169, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hmaeid, N.; Wali, M.; Metoui-Ben Mahmoud, O.; Pueyo, J.J.; Ghnaya, T.; Abdelly, C. Efficient rhizobacteria promote growth and alleviate NaCl-induced stress in the plant species Sulla carnosa. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2019, 133, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A.; Amaya, R.; Turgay, O.C.; Yaprak, A.E.; Taniguchi, T.; Kataoka, R. High salt tolerant plant growth promoting rhizobacteria from the common ice-plant Mesembryanthemum crystallinum L. Rhizosphere 2019, 9, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faa, A.; Ia, A.; Jp, B. Growth stimulation and alleviation of salinity stress to wheat by the biofilm forming Bacillus pumilus strain FAB10. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2019, 143, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Egamberdieva, D.; Davranov, K.; Wirth, S.; Hashem, A.; Abd Allah, E.F. Impact of soil salinity on the plant-growth-promoting and biological control abilities of root associated bacteria. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 24, 1601–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naureen, A.; Nasim, F.U.; Choudhary, M.S.; Ashraf, M.; Grundler, F.M.W.; Schleker, A.S.S. A new endophytic fungus CJAN1179 isolated from the Cholistan desert promotes lateral root growth in arabidopsis and produces IAA through tryptophan-dependent pathway. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.X.; Luan, J.; Wang, L.F.; Li, H.; Wang, Q.H.; Wang, Z.Q.; Jin, Z.X.; Yu, F. Effect of the plant growth promoting rhizobacterium, Cronobacter sp. Y501, for Enhancing Drought Tolerance in Maize (Zea mays L.). J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 2786–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakor, R.; Mistry, H.; Bariya, H. Efficacy of indole-3-acetic acid-producing PGPFs and their consortium on physiological and biochemical parameters of Trigonella foenum-graecum L. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2023, 14, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Abulreesh, H.H.; Monjed, M.K.; Elbanna, K.; Samreen; Ahmad, I. Multifarious functional traits of free-living rhizospheric fungi, with special reference to Aspergillus spp. isolated from North Indian soil, and their inoculation effect on plant growth. Ann. Microbiol. 2021, 71, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeano, R.M.S.; Franco, D.G.; Chaves, P.O.; Giannesi, G.C.; Masui, D.C.; Ruller, R.; Correa, B.O.; Brasil, M.D.; Zanoelo, F.F. Plant growth promoting potential of endophytic Aspergillus niger 9-p isolated from native forage grass in Pantanal of Nhecola ndia region, Brazil. Rhizosphere 2021, 18, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, M.; Naziya, B.; Ansari, M.A.; Alomary, M.N.; AlYahya, S.; Almatroudi, A.; Thriveni, M.C.; Gowtham, H.G.; Singh, S.B.; Aiyaz, M.; et al. Bioprospecting of rhizosphere-resident fungi: Their role and importance in sustainable agriculture. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Maraghy, S.S.; Tohamy, T.A.; Hussein, K.A. Role of plant-growth promoting fungi (PGPF) in defensive genes expression of Triticum aestivum against wilt disease. Rhizosphere 2020, 15, 100223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naziya, B.; Murali, M.; Amruthesh, K.N. Plant growth-promoting fungi (PGPF) instigate plant growth and induce disease resistance in Capsicum annuum L. upon Infection with Colletotrichum capsici (Syd.) butler & bisby. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 41. [Google Scholar]

| Species | Pathway | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IAM | IPA | TAM | IAN | TSO | Non-Tryptophan Dependent | |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | ✓ | |||||

| Arthrobacter pascens | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Azospirillum brasilense | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Bacillus amyloliquefaciens | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Bacillus cereus | ✓ | |||||

| Bacillus thuringiensis | ✓ | |||||

| Erwinia herbicola | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Escherichia sp. | ✓ | |||||

| Herbaspirillum aquaticum | ✓ | |||||

| Lysinibacillus spp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Pseudomonas putida | ✓ | |||||

| Pseudomonas sp. | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Rhizobium tropici | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Serratia marcescens | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Variovorax boronicumulans | ✓ | |||||

| Aspergillus flavus | ✓ | |||||

| Astraeus odoratus | ✓ | |||||

| Bradyrhizobium japonicum | ✓ | |||||

| Candida tropicalis | ✓ | |||||

| Colletotrichum acutatum | ✓ | |||||

| Colletotrichum fructicola | ✓ | |||||

| Colletotrichum gloeosporioides | ✓ | |||||

| Cyanodermella asteris | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Fusarium delphinoides | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Fusarium proliferum | ✓ | |||||

| Gyrodon suthepensis | ✓ | |||||

| Laccaria bicolor | ✓ | |||||

| Lentinula edodes | ✓ | |||||

| Leptosphaeria maculans | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Magnaporthe oryzae | ✓ | |||||

| Metarhizium robertsii | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Neurospora crassa | ✓ | |||||

| Phlebopus portentosus | ✓ | |||||

| Piriformospora indica | ✓ | |||||

| Pisolithus albus | ✓ | |||||

| Pisolithus orientalis | ✓ | |||||

| Rhodosporidiobolus fluvialis | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | ✓ | |||||

| Scleroderma suthepense | ✓ | |||||

| Sporisorium scitamineum | ✓ | |||||

| Tricholoma vaccinum | ✓ | |||||

| Ustilago maydis | ✓ | |||||

| Xylaria sp. | ✓ | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Mu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Fu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, H.; Yu, X.; Ye, Z. Biosynthetic Pathways and Functions of Indole-3-Acetic Acid in Microorganisms. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2077. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11082077

Tang J, Li Y, Zhang L, Mu J, Jiang Y, Fu H, Zhang Y, Cui H, Yu X, Ye Z. Biosynthetic Pathways and Functions of Indole-3-Acetic Acid in Microorganisms. Microorganisms. 2023; 11(8):2077. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11082077

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Jintian, Yukang Li, Leilei Zhang, Jintao Mu, Yangyang Jiang, Huilan Fu, Yafen Zhang, Haifeng Cui, Xiaoping Yu, and Zihong Ye. 2023. "Biosynthetic Pathways and Functions of Indole-3-Acetic Acid in Microorganisms" Microorganisms 11, no. 8: 2077. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11082077

APA StyleTang, J., Li, Y., Zhang, L., Mu, J., Jiang, Y., Fu, H., Zhang, Y., Cui, H., Yu, X., & Ye, Z. (2023). Biosynthetic Pathways and Functions of Indole-3-Acetic Acid in Microorganisms. Microorganisms, 11(8), 2077. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11082077