Simulation of Engine Power Requirement and Fuel Consumption in a Self-Propelled Crop Collector

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

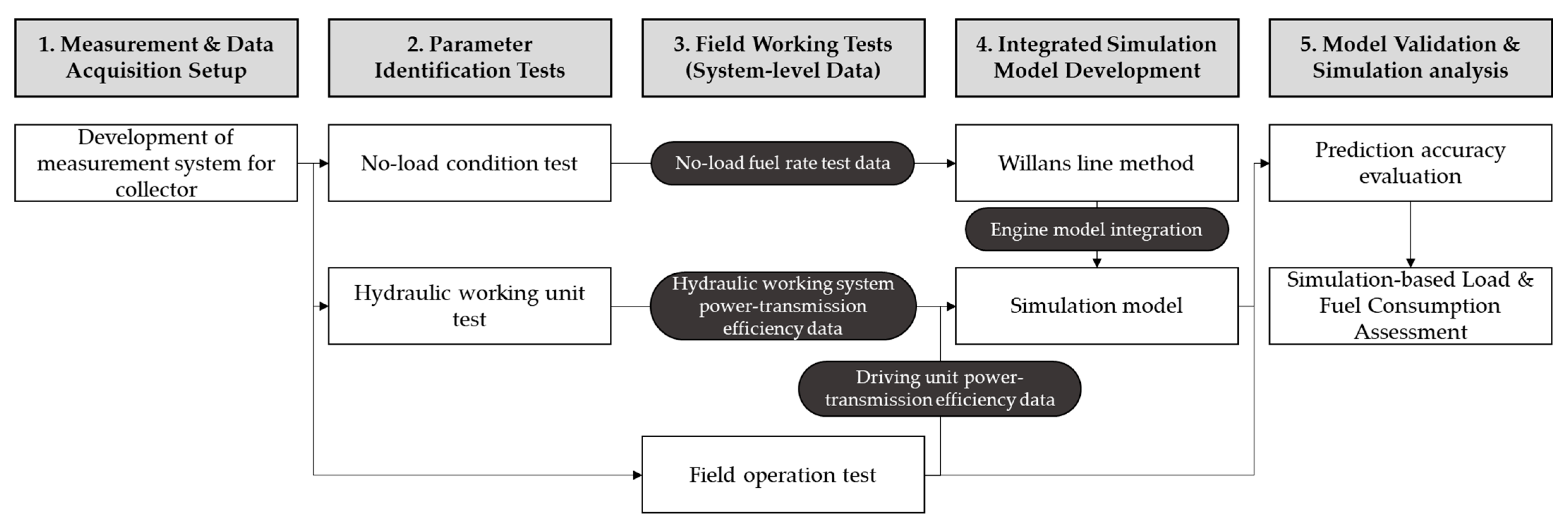

2.1. Development Process of Simulation Model

- Measurement and Data Acquisition Setup: A measurement system was configured to measure the power requirements of the collector’s major operating units and to characterize engine fuel-consumption behavior.

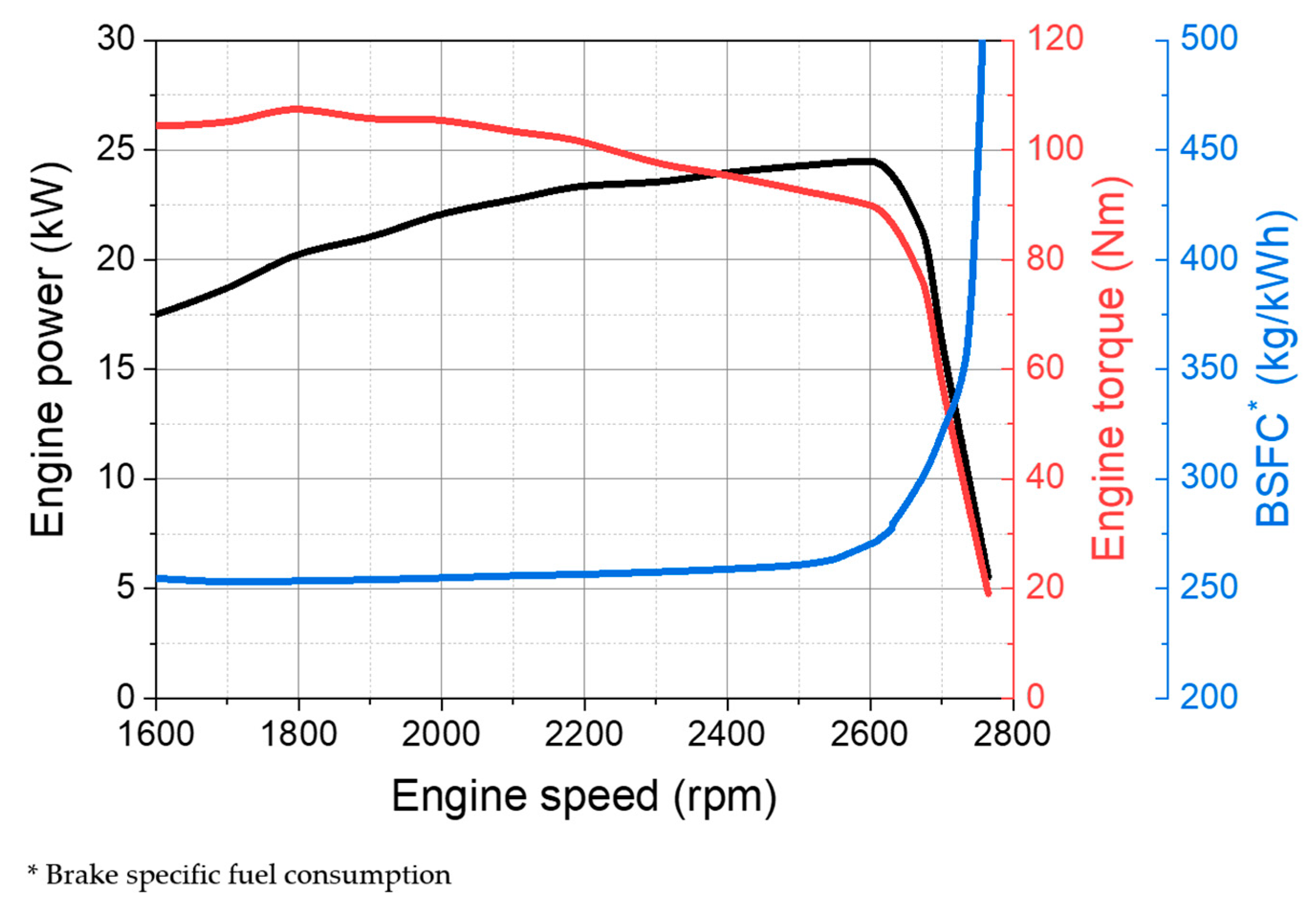

- Parameter Identification Tests: Fuel consumption under no-load conditions was measured and combined with the engine full-load curve to identify a Willans line-based engine model. In addition, standalone tests of the collecting and sorting units were conducted to estimate the power-transmission efficiency of the hydraulic working system.

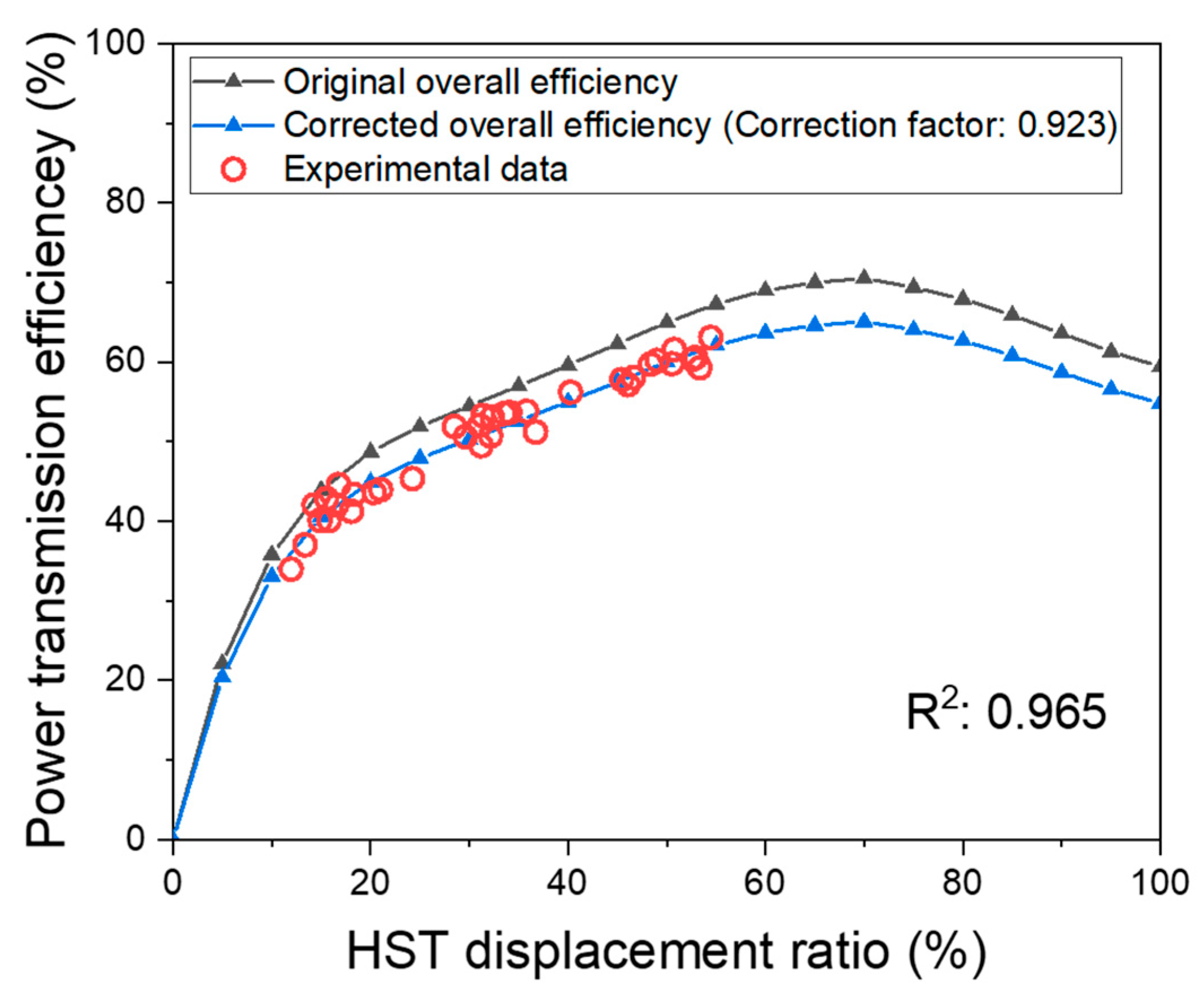

- Field Working Tests (System-Level Data): Field experiments under real operating conditions were performed to further determine the power-transmission efficiency of driving unit and to acquire system-level datasets for model validation.

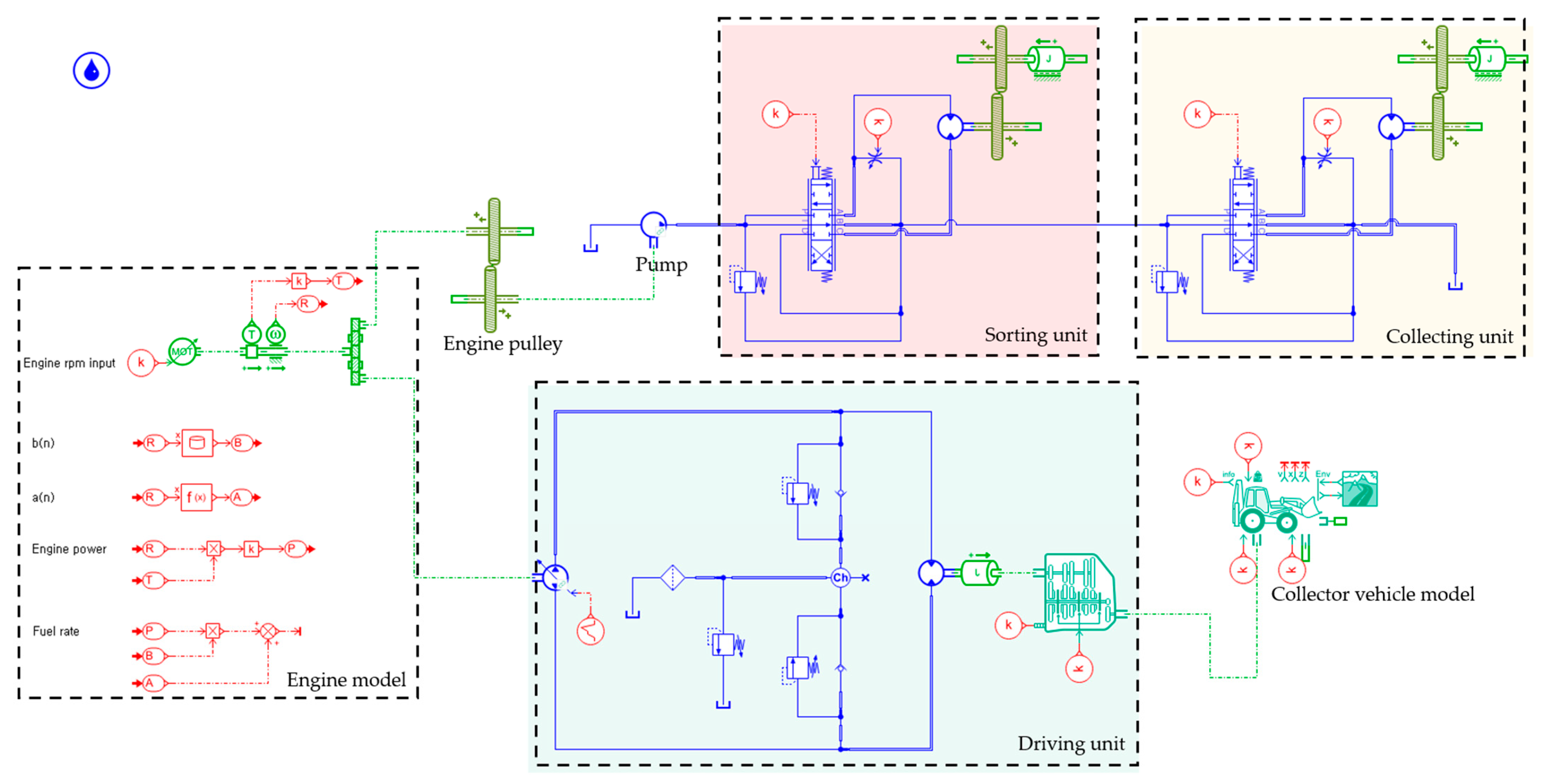

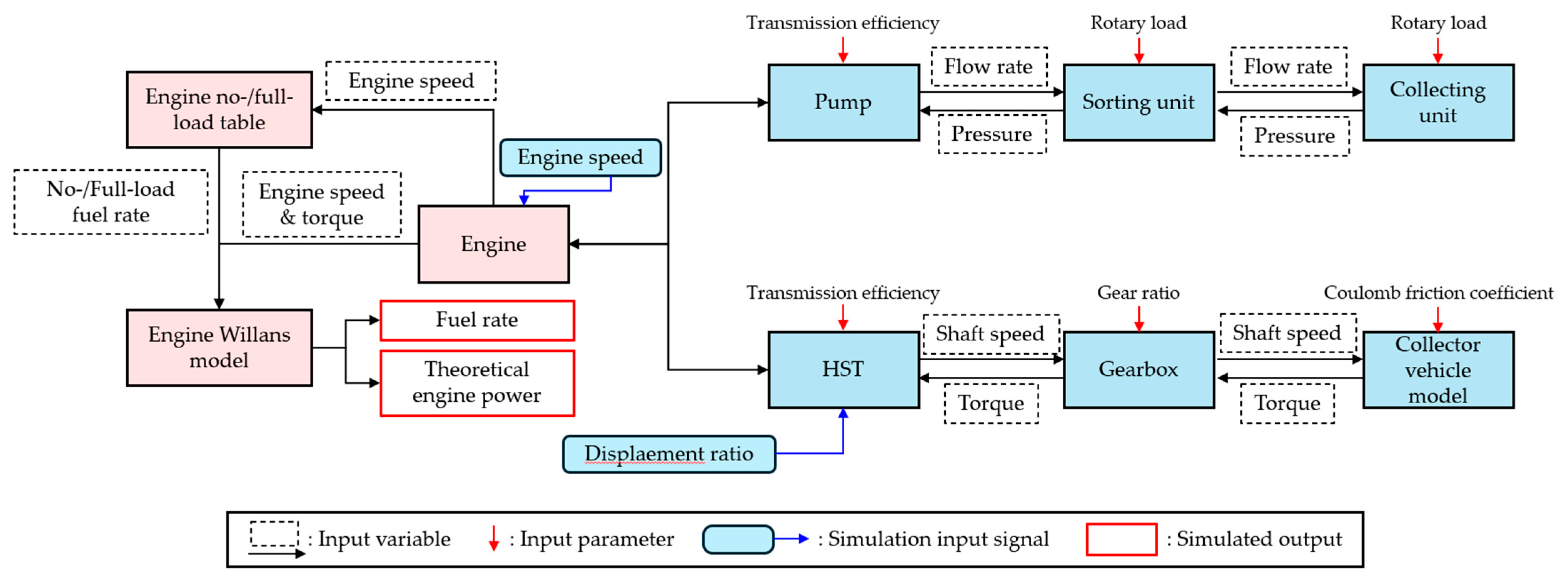

- Integrated Simulation Model Development: A comprehensive simulation model of the self-propelled collector was developed by integrating the Willans line-based engine model with the machine’s subsystem models.

- Model Validation and Simulation Analysis: The reliability of the developed simulation model was verified, and the model was adopted to assess engine power and fuel consumption characteristics across a wide range of operating scenarios.

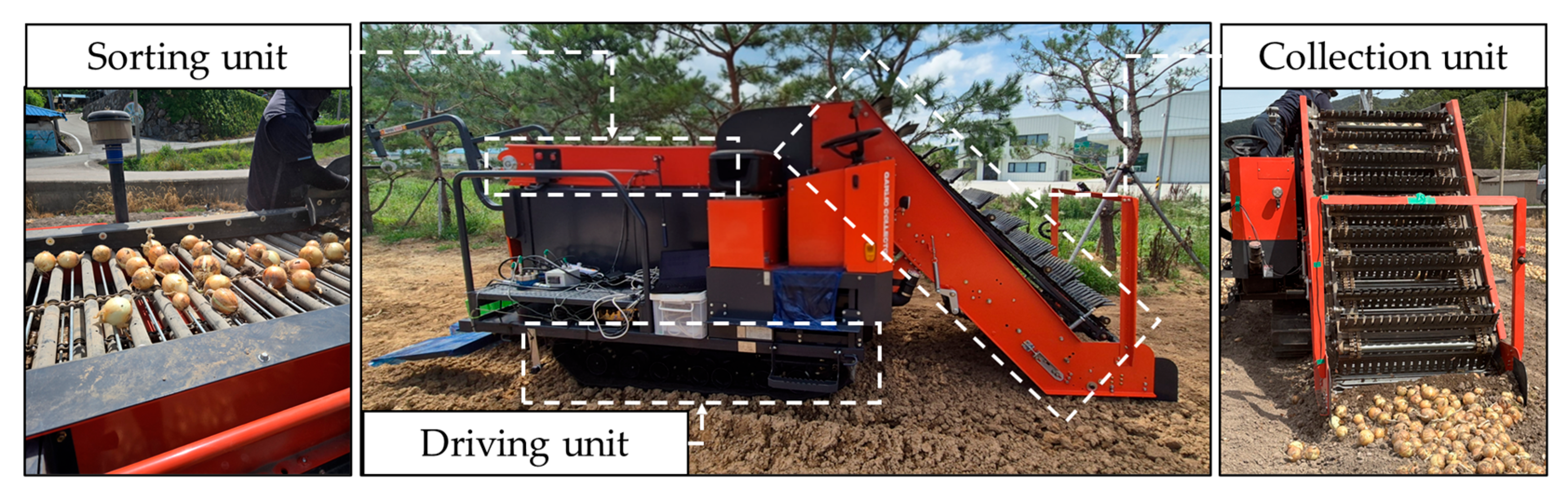

2.2. Self-Propelled Collector

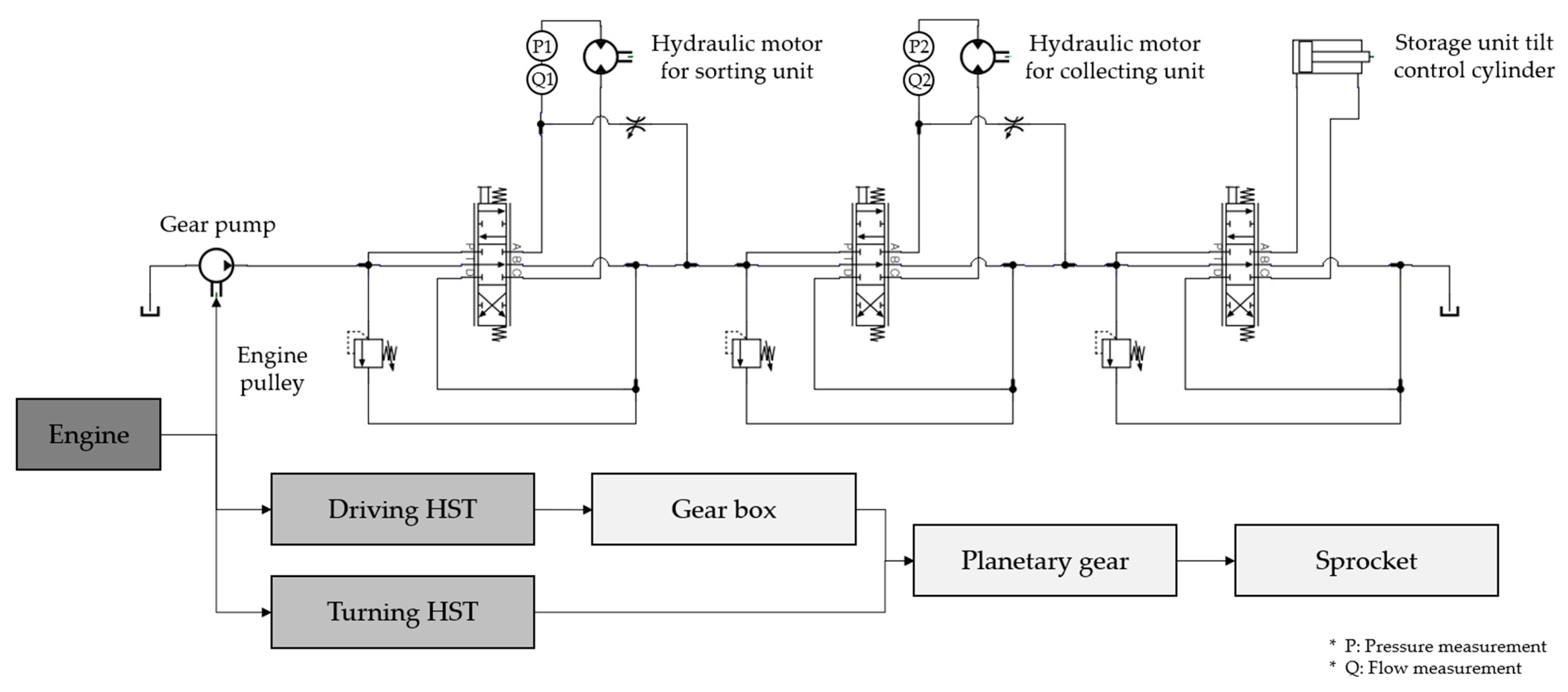

2.3. Power Transmission and Hydraulic System Configuration

2.4. Measurement System

2.5. Field Test

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Simulation Model

3. Results

3.1. Measurement Result

3.1.1. No-Load Fuel Rate

3.1.2. Collecting-Sorting Unit Measurement Result

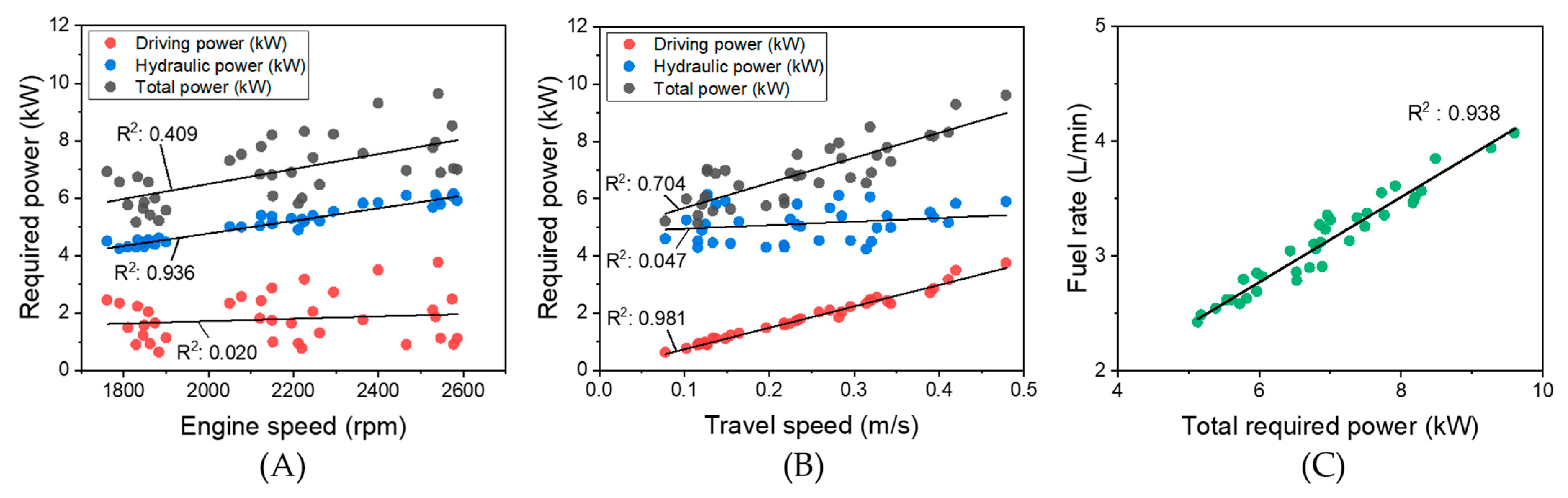

3.1.3. Measurement Result of Self-Propelled Collector Under Various Working Conditions

3.2. Development of Self-Propelled Collector Simulation Model

3.2.1. Simulation Model Development

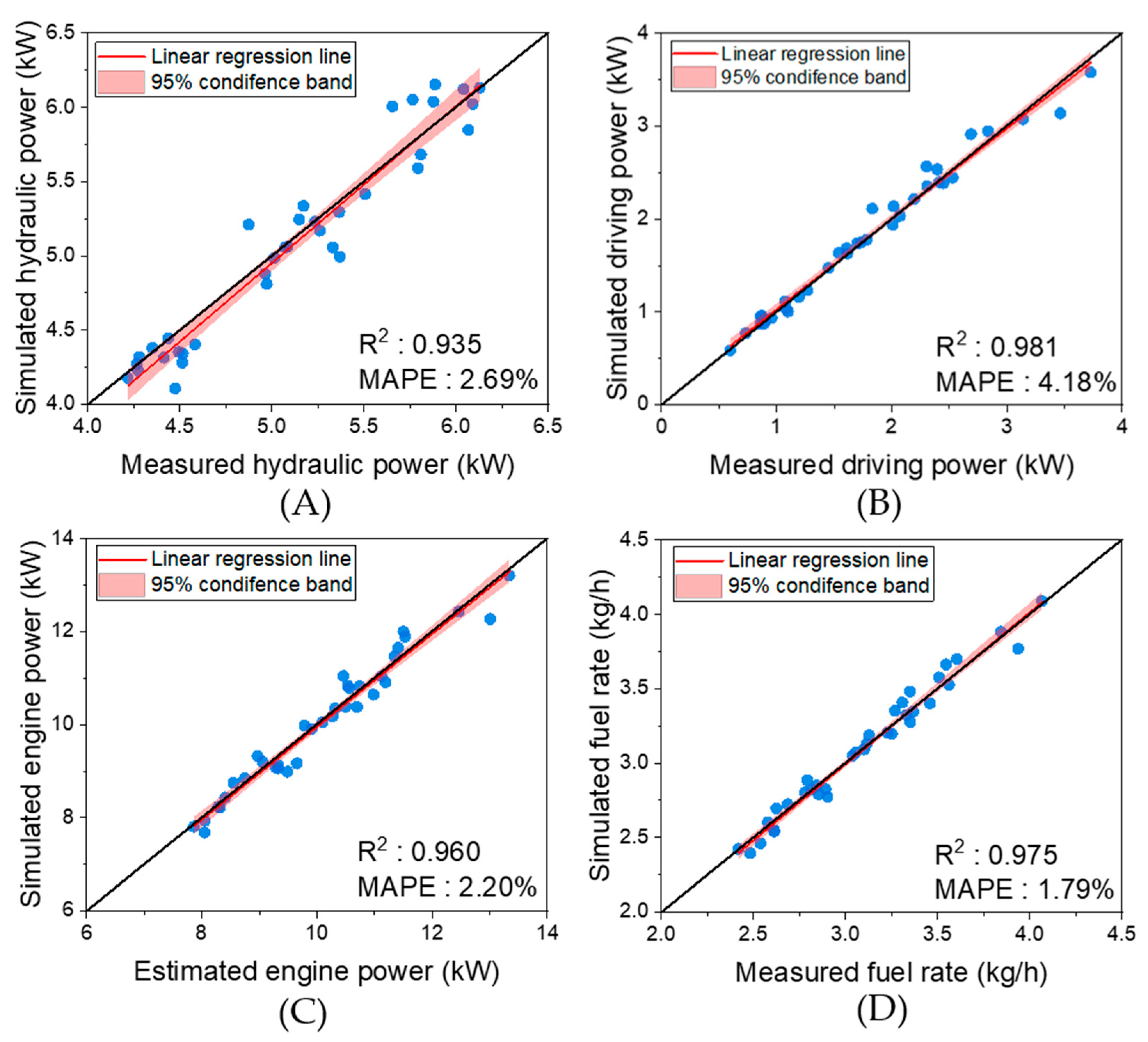

3.2.2. Simulation Model Validation

3.3. Evaluation of Engine Power and Fuel Efficiency of Self-Propelled Collector

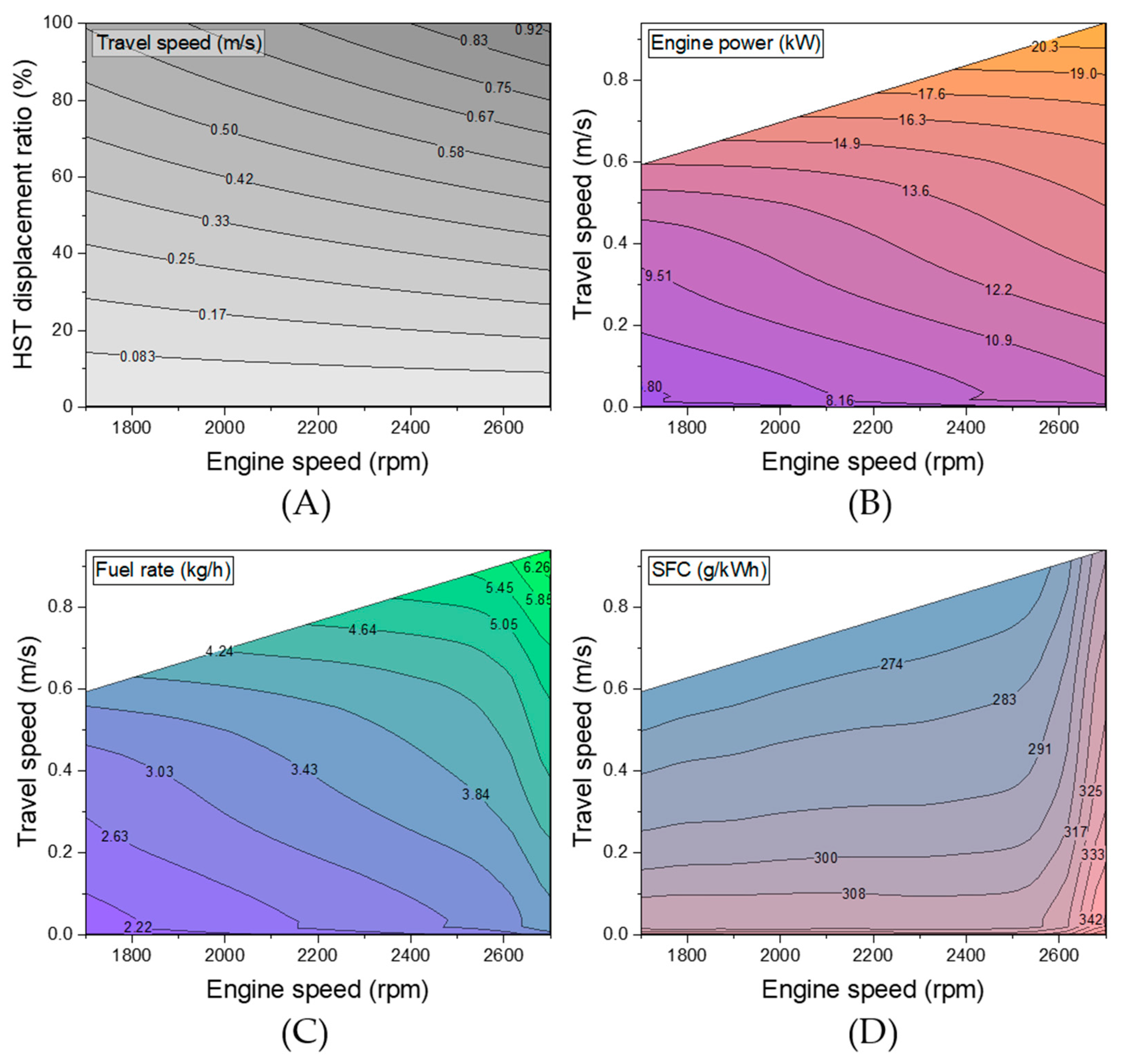

3.3.1. Simulation-Based Evaluation of Engine Power and Fuel Efficiency

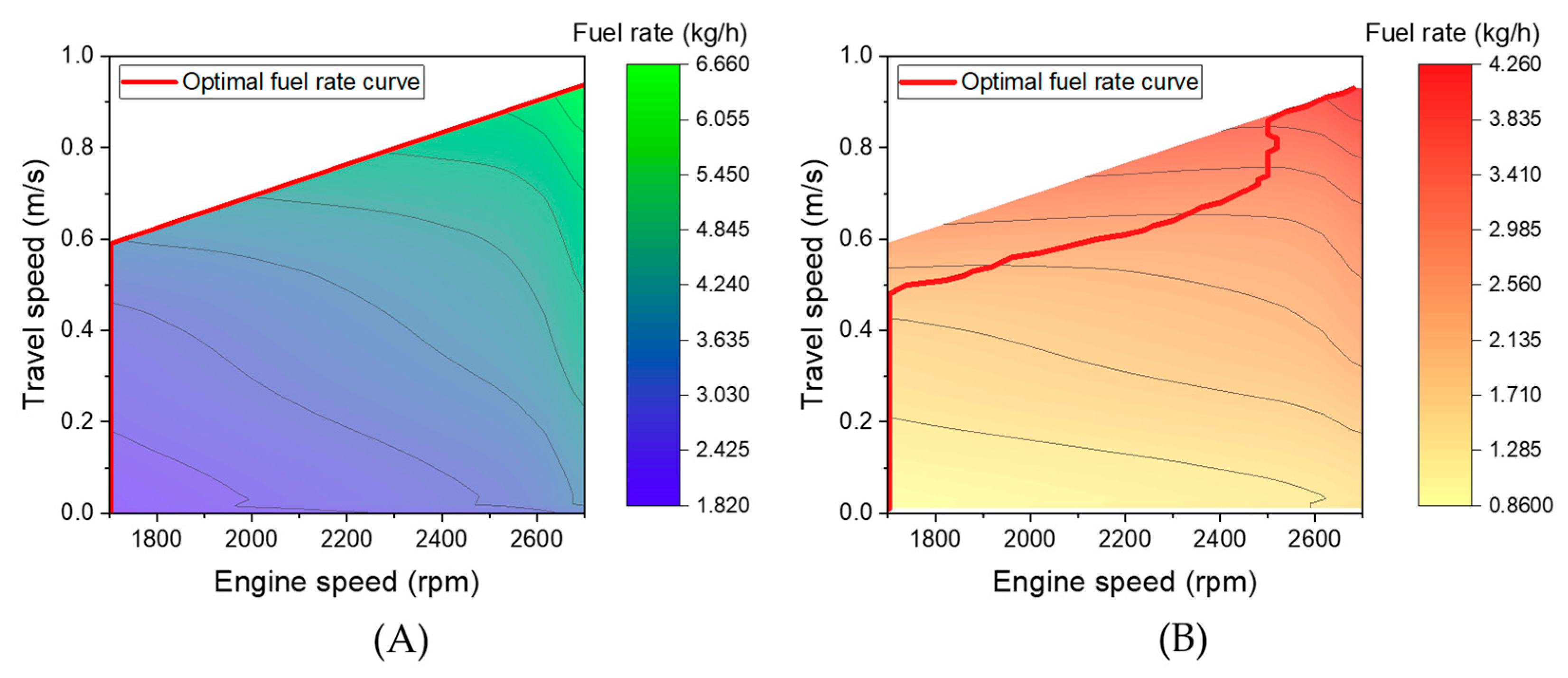

3.3.2. Comparison of Fuel Rate and Optimal Operating Points Between Full Collector System and Driving Unit Only

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The Willans-line-based modeling approach, calibrated using installed no-load fuel rate and manufacturer engine maps, provides a practical and robust means of estimating engine power for small agricultural machines that lack direct CAN/ECU-based power signals. By focusing on a net (effective) installed brake power basis, the framework avoids separate parasitic-loss modeling while remaining sufficiently accurate for system-level simulation and design.

- A comprehensive analysis of the simulation results revealed that both engine speed and travel speed strongly affect the distribution of engine power between the hydraulic working units and the driving unit, as well as the overall fuel rate and SFC. Operating near 1700 rpm with an HST displacement ratio of approximately 80–82% was identified as an efficient operating region, and the hydraulic working units were found to be the dominant contributors to total power demand, particularly at higher engine speeds.

- The simulation results indicated that reducing hydraulic load is the most effective means of improving fuel efficiency, suggesting that design and control strategies for compact self-propelled collectors should prioritize minimizing hydraulic power demand, for example, through the adoption of variable-displacement pumps, optimized displacement control according to crop load and desired travel speed, and improved hydraulic circuit and HST gear-ratio design.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Field | Actual Engine Speed (rpm) | Travel Speed (m/s) | Pump Pressure (bar) | Pump Flow Rate (L/min) | Total Sprocket Torque (Nm) | Average Sprocket Rotational Speed (rpm) | Required Hydraulic Power (kW) | Required Driving Power (kW) | Fuel Rate (kg/h) | Theoretical Engine Power (kW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1831 | 0.116 | 145 | 17.7 | 711 | 11.6 | 4.27 | 0.86 | 3.37 | 7.87 |

| 1812 | 0.197 | 145 | 17.7 | 706 | 19.7 | 4.28 | 1.46 | 3.50 | 8.41 | |

| 1792 | 0.315 | 144 | 17.6 | 702 | 31.5 | 4.22 | 2.31 | 3.71 | 9.29 | |

| 2213 | 0.121 | 140 | 20.9 | 715 | 12.1 | 4.88 | 0.91 | 3.82 | 8.98 | |

| 2151 | 0.232 | 148 | 20.6 | 701 | 23.2 | 5.07 | 1.71 | 4.09 | 10.11 | |

| 2052 | 0.344 | 140 | 21.3 | 641 | 34.4 | 4.97 | 2.31 | 4.12 | 10.32 | |

| 2580 | 0.128 | 149 | 24.7 | 657 | 12.8 | 6.13 | 0.88 | 4.61 | 10.75 | |

| 2537 | 0.282 | 149 | 24.6 | 620 | 28.2 | 6.09 | 1.83 | 4.74 | 11.51 | |

| 2296 | 0.390 | 148 | 22.4 | 660 | 39.0 | 5.51 | 2.69 | 4.52 | 11.42 | |

| B | 1902 | 0.134 | 144 | 18.5 | 787 | 13.4 | 4.44 | 1.10 | 3.52 | 8.30 |

| 1876 | 0.218 | 141 | 18.6 | 710 | 21.8 | 4.35 | 1.62 | 3.62 | 8.75 | |

| 1834 | 0.296 | 146 | 18.6 | 709 | 29.6 | 4.52 | 2.20 | 3.83 | 9.66 | |

| 2264 | 0.165 | 143 | 21.7 | 736 | 16.5 | 5.17 | 1.27 | 4.10 | 9.92 | |

| 2248 | 0.286 | 149 | 21.7 | 675 | 28.6 | 5.37 | 2.02 | 4.25 | 10.54 | |

| 2228 | 0.412 | 143 | 21.6 | 730 | 41.2 | 5.15 | 3.15 | 4.45 | 11.36 | |

| 2588 | 0.149 | 143 | 24.7 | 694 | 14.9 | 5.89 | 1.08 | 4.55 | 10.47 | |

| 2576 | 0.319 | 148 | 24.5 | 733 | 31.9 | 6.04 | 2.45 | 5.07 | 12.48 | |

| 2543 | 0.479 | 146 | 24.2 | 743 | 47.9 | 5.88 | 3.73 | 5.24 | 13.35 | |

| C | 1885 | 0.078 | 147 | 18.7 | 736 | 7.8 | 4.59 | 0.60 | 3.44 | 8.06 |

| 1848 | 0.155 | 150 | 17.7 | 738 | 15.5 | 4.42 | 1.20 | 3.49 | 8.32 | |

| 1860 | 0.259 | 145 | 18.7 | 741 | 25.9 | 4.52 | 2.01 | 3.76 | 9.33 | |

| 2154 | 0.125 | 147 | 20.8 | 735 | 12.5 | 5.09 | 0.96 | 3.88 | 9.33 | |

| 2123 | 0.238 | 152 | 19.8 | 719 | 23.8 | 5.01 | 1.79 | 4.00 | 9.80 | |

| 2079 | 0.327 | 151 | 19.8 | 740 | 32.7 | 4.96 | 2.53 | 4.22 | 10.71 | |

| 2468 | 0.127 | 148 | 24.7 | 652 | 12.7 | 6.07 | 0.87 | 4.42 | 10.51 | |

| 2366 | 0.233 | 147 | 23.7 | 709 | 23.3 | 5.80 | 1.73 | 4.54 | 11.20 | |

| 2126 | 0.339 | 149 | 21.7 | 675 | 33.9 | 5.37 | 2.40 | 4.31 | 10.99 | |

| D | 1864 | 0.117 | 149 | 18.1 | 734 | 11.7 | 4.50 | 0.90 | 3.43 | 8.06 |

| 1850 | 0.219 | 142 | 18.1 | 676 | 21.9 | 4.28 | 1.55 | 3.56 | 8.56 | |

| 1763 | 0.321 | 149 | 18.0 | 720 | 32.1 | 4.48 | 2.42 | 3.76 | 9.50 | |

| 2222 | 0.103 | 145 | 21.7 | 685 | 10.3 | 5.24 | 0.74 | 3.85 | 9.07 | |

| 2197 | 0.225 | 145 | 21.7 | 684 | 22.5 | 5.26 | 1.61 | 4.15 | 10.28 | |

| 2152 | 0.394 | 147 | 21.7 | 688 | 39.4 | 5.33 | 2.84 | 4.35 | 11.13 | |

| 2549 | 0.137 | 145 | 23.9 | 759 | 13.7 | 5.77 | 1.09 | 4.52 | 10.57 | |

| 2530 | 0.272 | 141 | 24.1 | 729 | 27.2 | 5.66 | 2.08 | 4.74 | 11.54 | |

| 2402 | 0.420 | 148 | 23.6 | 788 | 42.0 | 5.81 | 3.47 | 5.05 | 13.02 |

References

- Seok, J.H.; Moon, H.; Kim, G.; Reed, M.R. Is aging the important factor for sustainable agricultural development in Korea? Evidence from the relationship between aging and farm technical efficiency. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Korea. 2024 Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Survey; Statistics Korea: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H.; Cho, Y.H.; Kim, K.M.; Lee, C.Y.; Lee, W.S.; Nam, J.S. Sweet potato farming in the USA and South Korea: A comparative study of cultivation pattern and mechanization status. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2025, 50, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shan, C.; Gou, F.; Qian, Z.; Ni, Y.; Liu, Z.; Jin, C. A review of key technologies and intelligent applications in soybean mechanized harvesting: Chinese and international perspectives. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2025, 50, 79–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhiram, G. The evolution of tea harvesting: A comprehensive review of machinery and technological advancements. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 49, 346–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Agricultural Sciences. A Study on the Using State of Agricultural Machinery and Mechanized Rate; Rural Development Administration: Jeonju, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, A.; Peng, B.; Yang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Zou, X.; Zhu, Z. Design of a Machine Vision-Based Automatic Digging Depth Control System for Garlic Combine Harvester. Agriculture 2022, 12, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, C.Y.; Cho, Y.H.; Yu, Z.; Kim, K.M.; Yang, Y.J.; Nam, J.S. Potato farming in the United States and South Korea: Status comparison of cultivation patterns and agricultural machinery use. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 49, 252–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiraga, S.; Reza, M.N.; Lee, K.H.; Gulandaz, M.A.; Karim, M.R.; Habineza, E.; Kabir, M.S.; Lee, D.H.; Chung, S.O. Vibration and slope harvesting conditions affect real-time vision-based radish volume measurements: Experimental study using a laboratory test bench. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2025, 50, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouriya, A.; Kumar, P.; Tewari, V.K.; Singh, N. Development of a low-cost telemetry system for draft measurement of agriculture implements. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 49, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Raheman, H. Development of a novel draft sensing device with lower hitch attachments for tractor-drawn implements. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 49, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Yan, X.; Tang, H. Method of controlling tillage depth for agricultural tractors considering engine load characteristics. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 227, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Yang, Z.; Mowafy, S.; Zheng, B.; Song, Z.; Luo, Z.; Guo, W. Load characteristics analysis of tractor drivetrain under field plowing operation considering tire–soil interaction. Soil Tillage Res. 2023, 227, 105620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolator, B.; Białobrzewski, I. A simulation model of 2WD tractor performance. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2011, 76, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, I.A.; de Freitas Coelho, A.L.; de Queiroz, D.M.; Furtado Junior, M.R.; Villibor, G.P. Development of software for performance analysis of wheeled tractors. J. Terramech. 2025, 119, 101054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zeng, L.; Chen, L.; Zou, R.; Cai, Y. Fuzzy Adaptive Energy Management Strategy for a Hybrid Agricultural Tractor Equipped with HMCVT. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.; Yuan, F.; Lu, Z. A Multi-Objective Optimization Method for a Tractor Driveline Based on the Diversity Preservation Strategy of Gradient Crowding. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, D.; Cai, Y.; Lai, L. Energy Saving Performance of Agricultural Tractor Equipped with Mechanic-Electronic-Hydraulic Powertrain System. Agriculture 2022, 12, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacour, S.; Burgun, C.; Perilhon, C.; Descombes, G.; Doyen, V. A model to assess tractor operational efficiency from bench test data. J. Terramech. 2014, 54, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-de-Soto, M.; Emmi, L.; García, I.; Gonzalez-de-Santos, P. Reducing fuel consumption in weed and pest control using robotic tractors. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2015, 114, 96–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanauskas, V.; Janulevičius, A. Differences in tractor performance parameters between single-wheel 4WD and dual-wheel 2WD driving systems. J. Terramech. 2015, 60, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachernegg, S.J. A Closer Look at the Willans-Line; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukovic, M.; Leifeld, R.; Murrenhoff, H. Reducing Fuel Consumption in Hydraulic Excavators—A Comprehensive Analysis. Energies 2017, 10, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milićević, S.; Blagojević, I.; Milojević, S.; Bukvić, M.; Stojanović, B. Numerical Analysis of Optimal Hybridization in Parallel Hybrid Electric Powertrains for Tracked Vehicles. Energies 2024, 17, 3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Specification | |

|---|---|---|

| Collector | Dimension (L × W × H) (mm) | 5580 × 2205 × 2100 |

| Curb weight (kg) | 3170 | |

| Pump displacement (cm3/rev) | 14 | |

| Transmission ratio of engine pulley (Engine: Pump) | 30:21 | |

| Hydraulic working system | Displacement of collecting unit motor (cm3/rev) | 130 |

| Displacement of sorting unit motor (cm3/rev) | 100 | |

| Relief pressure (bar) | 220 | |

| Width of collecting unit (mm) | 1240 | |

| Hydraulic oil grade | ISO VG 32 | |

| HST | Maximum pump displacement (cm3/rev) | 45 |

| Motor displacement (cm3/rev) | 45 | |

| Relief pressure (bar) | 380 | |

| Travel speed by auxiliary mechanical transmission stage (m/s) | Low: 0–0.9 Standard: 0–1.5 High: 0–2.5 | |

| Driving unit | Pitch circle diameter of sprocket (mm) | 191 |

| Track width (mm) | 450 | |

| Track contact length (mm) | 1580 | |

| Item | Specifications |

|---|---|

| Dimension (L × W × H) (mm) | 615 × 495 × 628 |

| Dry weight (kg) | 178 |

| Type | 3-cylinder, 4-cycle, Diesel |

| Displacement (cm3) | 1647 |

| Cylinder bore × stroke (mm) | Ø87 × 92.4 |

| Combustion system | Indirect Injection |

| Rated power (kW) | 25.4 @2600rpm |

| Maximum torque (Nm) | 105 @1700 rpm |

| Idle/Maximum speed (rpm) | 1000/2800 |

| Aspiration | Naturally aspirated |

| Compression ratio | 21.7:1 |

| Governor type | Mechanical |

| Emission regulation | EPA Tier 4 EEC Stage 3A |

| Fuel supply system | Forced feed |

| Item | Specification | |

|---|---|---|

| Data logger (SV_S4a, Manner, Munich, Germany) | Maximum sampling rate (Hz) | 4000 |

| Resolution (bit) | 16 | |

| Bridge type | Full Bridge | |

| Data receiver (AW_P, Manner) | Maximum sampling rate (Hz) | 4000 |

| Resolution (bit) | 16 | |

| Output signal bandwidth (Hz) | 0–1000 | |

| Sprocket torque (KFGS-2-350-D31-11, KYOWA, Tokyo, Japan) | Calibration factor of left sprocket | 396.65 Nm/V |

| Calibration factor of right sprocket | 393.35 Nm/V | |

| Allowable error (%) | 0.1 | |

| Gauge factor tolerance (%) | 1 | |

| Encoder (E50S8, Autonics, Yangsan, South Korea) | Resolution (pulses/rev) | 3600 |

| Maximum speed (rpm) | 5000 | |

| Flowmeter of motor (HysenseQG100, Hydrotechnik, Limburg, Germany) | Measurement range (L/min) | 0.7–70 |

| Accuracy (%) | 0.4 (±0.3 L/min) | |

| Pressure sensor (HysensePR130, Hydrotechnik) | Range (bar) | 0–250 |

| Accuracy (%) | 0.5 (±1.25 bar) | |

| Non-linearity (%) | 0.4 (±1 bar) | |

| Photodetector (BRQT100, Autonics) | Detection distance (mm) | 100 |

| Response time (ms) | ≤1 | |

| Flowmeter of fuel line (OG2, Titan Enterprise, Dorset, UK) | Measurement range (L/min) | 0.03–4 |

| Accuracy (%) | 0.75 (±0.03 L/min) | |

| Repeatability (%) | 0.1 (±0.04 L/min) | |

| Resolution (pulses/L) | 1100 | |

| DAQ (MX840B, Manner) | Channels | 8 |

| Maximum sampling rate (Hz) | 40,000 | |

| GNSS | RTK accuracy (mm) | ≤10 + 1 parts per million |

| Convergence time (s) | ≤10 | |

| Navigation update rate (Hz) | ≤8 | |

| Field | Location | Crop | Cone index (kPa) | SMC 1 (%) | Soil Texture | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–5 cm | 5–10 cm | 10–15 cm | 15–20 cm | |||||

| A | 35°37′16.9″ N 128°21′26.7″ E | Southern-type garlic | 70 | 580 | 984 | 1144 | 29.64 | Silt loam |

| B | 35°37′40.8″ N 128°19′2.9″ E | Paddy-field onion | 38 | 355 | 622 | 739 | 29.68 | Silt loam |

| C | 34°58′6.6″ N 126°27′18.2″ E | Upland onion | 316 | 581 | 776 | 1604 | 32.14 | Loam |

| D | 36°19′58.6″ N, 128°42′ 17.0″ E | Northern-type garlic | 155 | 217 | 288 | 768 | 26.77 | Loam |

| Item | Specifications |

|---|---|

| Oil density (kg/m3) | 840 |

| Oil bulk modulus (bar) | 13,000 |

| Oil absolute viscosity (cP) | 32 |

| Gear ratio of collecting unit (–) | 5:11 |

| Gear ratio of sorting unit (–) | 5:7 |

| Transmission ratio of row gear stage (–) | 287:10 |

| Total static vehicle mass (kg) | 3320 |

| Coulomb friction coefficient (–) | 0.228 |

| Rear wheel radius (mm) | 95.5 |

| Hydraulic-mechanical efficiency of crop collection system pump (–) | 0.72 |

| Hydraulic-mechanical efficiency of HST pump (–) | Defined as HST displacement ratio |

| Initial Engine Speed (rpm) | Operating Mode | Actual Engine Speed (rpm) | Sorting Unit Motor | Collecting Unit Motor | Fuel Rate (kg/h) | 1 (kW) | 2 (kW) | 3 (-) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure (bar) | Flow Rate (L/min) | Pressure (bar) | Flow Rate (L/min) | |||||||

| 2000 | Collection only | 1905 | 97.8 | 15.02 | 97.8 | 0.01 | 1.642 | 3.07 | 4.30 | 0.715 |

| Sorting only | 1938 | 42.5 | 0.02 | 42.5 | 18.86 | 1.105 | 1.31 | 1.83 | 0.716 | |

| Both operate | 1870 | 150.2 | 16.61 | 150.2 | 18.55 | 1.959 | 4.18 | 5.78 | 0.723 | |

| 2300 | Collection only | 2261 | 97.9 | 15.15 | 97.9 | 0.00 | 1.921 | 3.65 | 5.07 | 0.720 |

| Sorting only | 2279 | 42.9 | 0.02 | 42.9 | 22.36 | 1.279 | 1.56 | 2.18 | 0.717 | |

| Both operate | 2235 | 147.1 | 17.52 | 147.1 | 21.73 | 2.260 | 4.79 | 6.62 | 0.724 | |

| 2600 | Collection only | 2571 | 100.0 | 17.86 | 100.0 | 0.01 | 2.229 | 4.23 | 5.88 | 0.720 |

| Sorting only | 2643 | 43.5 | 0.03 | 43.5 | 25.40 | 1.508 | 1.79 | 2.50 | 0.719 | |

| Both operate | 2596 | 149.8 | 18.16 | 149.8 | 25.82 | 2.746 | 5.80 | 7.98 | 0.726 | |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | r * | * | t * | Adj. R2 | Equation | F * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engine power (kW) | Engine speed | 0.544 | 0.358 | 135.6 | 0.983 | 72,001 | |

| Travel speed | 0.928 | 0.849 | 317.2 | ||||

| Fuel rate (kg/h) | Engine speed | 0.674 | 0.512 | 140.4 | 0.968 | 38,225 | |

| Travel speed | 0.848 | 0.735 | 201.6 | ||||

| SFC (g/kWh) | Engine speed | 0.256 | 0.444 | 44.2 | 0.761 | 3974 | |

| Travel speed | −0.757 | −0.855 | −85.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Min, Y.-S.; Do, Y.-W.; Yun, Y.; Lee, S.-H.; Kwon, S.-G.; Kim, W.-S. Simulation of Engine Power Requirement and Fuel Consumption in a Self-Propelled Crop Collector. Actuators 2026, 15, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010008

Min Y-S, Do Y-W, Yun Y, Lee S-H, Kwon S-G, Kim W-S. Simulation of Engine Power Requirement and Fuel Consumption in a Self-Propelled Crop Collector. Actuators. 2026; 15(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleMin, Yi-Seo, Young-Woo Do, Youngtae Yun, Sang-Hee Lee, Seung-Gwi Kwon, and Wan-Soo Kim. 2026. "Simulation of Engine Power Requirement and Fuel Consumption in a Self-Propelled Crop Collector" Actuators 15, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010008

APA StyleMin, Y.-S., Do, Y.-W., Yun, Y., Lee, S.-H., Kwon, S.-G., & Kim, W.-S. (2026). Simulation of Engine Power Requirement and Fuel Consumption in a Self-Propelled Crop Collector. Actuators, 15(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/act15010008